Factors Affecting the Delivery and Acceptability of the ROWTATE Telehealth Vocational Rehabilitation Intervention for Traumatic Injury Survivors: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Data

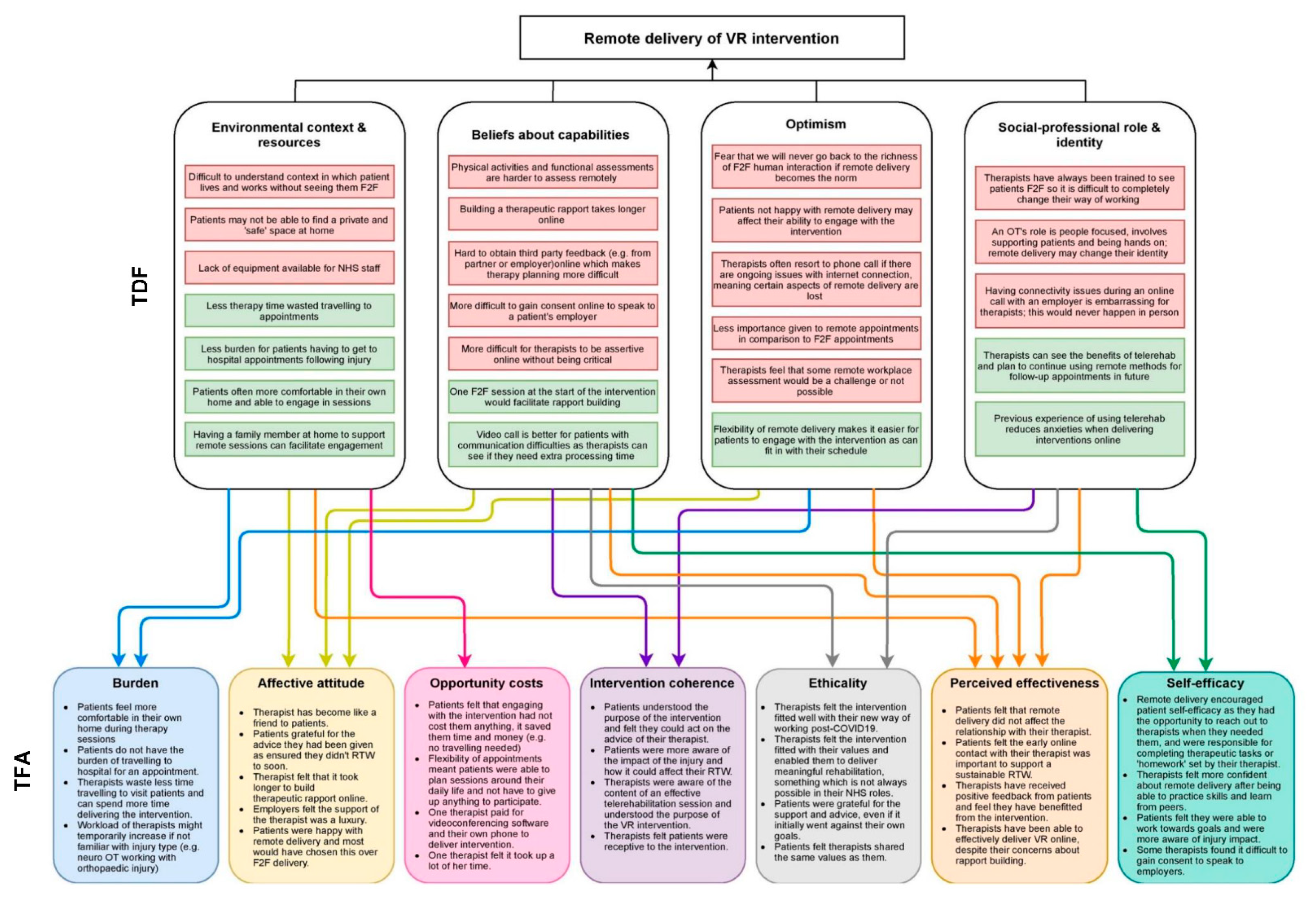

3.2. Qualitative Data

3.2.1. Pre-Intervention Interviews

Environmental Context and Resources

‘When we’ve been doing video conferencing since April, it’s bonkers that we haven’t got enough computers. I mean it’s daft when you’re in the unit to do video calls. It’s, “Well, I need a laptop.” “I’m doing a video call.” So we actually have to use a diary, ridiculously, to make sure there’s no more than two of us trying to do a video call at once because we haven’t got any more laptops to do it from.’(OT03)

‘If it’s a home visit and you’re seeing somebody in their own environment, you can get a sense of that [context]… get a sense of how people are living and observe where they’re at in ways that you wouldn’t get [remotely].’(CP06)

‘It’s whether there’s a room available and space available. So yeah, that becomes tricky. And obviously you need that private space, don’t you, to do the video calling? You can’t just do that anywhere, and for privacy for the patient, they need that confidentiality that you’re in a room on your own…room usage is a real issue.’(OT03)

‘You can fit it [therapy session] in around your working week… maybe you could check in with someone a little bit more often rather than waiting for that face-to-face appointment.’(CP02)

Beliefs about Capabilities

‘I think if you’re wanting to do more complex cognitive assessments, I think that might be a bit more challenging, particularly with wanting to see how the person approaches the task and you’re more interested in that than the actual answers and score.’(OT07)

‘I just couldn’t get the rapport because he’s [patient] so low. He’s low, he’s anxious, he’s fed up, he just says, “I don’t know,” all the time. I just couldn’t get anywhere with a telephone call with him, and now I’ve started to get somewhere. He’s one of the ones I’ve prioritised as face to face because work were going to kick him out…now I’m seeing him face to face it’s completely different.’(OT03)

‘I think if I have sufficient training and maybe problem solving and group work in terms of learning from others how they have done it so far, then—and maybe it will increase knowledge and skill and that, it will improve even more.’(OT04)

‘I think when we first started doing it [remote delivery] we were a bit like, oh God, what can I do on a video call? Because if you’d asked me six months ago, “Could you do some of your job on video calls?” I’d be like, “No, I need to see patients face-to-face. Don’t be ridiculous”…“Of course I can’t do hand function [assessments]. I can’t touch their hands,” but you’ve got a relative next to them, they’re showing you the [movement] range, or if you’ve got a really good carer, you might be able to do some of that. So, we’ve evolved hugely in what we think we can do, and that’s definitely from listening to each other.’(OT03)

‘I think I’d be a lot more confident having had experience of delivering it with stroke patients. And certainly I’ve learned stuff from my training as well, or we’ve been learning together about how to deliver kind of more—slightly more complex kind of information.’(CP02)

Optimism

‘If you’re going to have someone that is more in construction, I think that is impossible because no one’s going to walk around with an iPad and tell you exactly. And you won’t be able to do a physical assessment in terms of the space and what it does entail and everything like that.’(OT04)

‘Then the other issues are just about whether the participants, the patients, will have the right technology to be able to take part…I can imagine for individuals—thinking about people I’ve worked with in the past—there can be a real reticence or some concern about doing things remotely.’(CP06)

‘Everybody’s had enough of not seeing people face to face. It’s just not human…I fear that the more work we all do to adapt things, the more likely it is that we’re never going to go back to how it was before…that’s my key worry about all of this, is that at some point it may just be that we never go back to having the richness of human involvement.’(OT05)

‘It’s good because I think it probably has revolutionised how we’re doing things.’(OT07)

‘Follow-up appointments would become a lot easier, I guess. I’m not sure I’d love to be doing initials over a video call for ever and a day, but then it serves its place. If you’ve got patients that are miles away, it still has its place…there are certain ones that I think lend themselves really well and, yeah, why wouldn’t you do a video call in the future?’(OT03)

Social/Professional Role and Identity

‘That’s been a challenge for me as a psychologist I think in providing that therapeutic relationship because it’s—my entire training, my entire working life has been based on face-to-face contact’(CP02)

3.2.2. Post-Intervention Interviews

Environmental Context and Resources

‘I’m not sure how that would be for someone who perhaps doesn’t work that much with IT in their daily work as I do. So I’m quite aware that it may well be much more of a problem for someone who perhaps has no Wi-Fi at home and would have to rely on mobile reception.’(Trauma survivor, polytrauma)

‘You know when like we’re talking at a camera, like an hour and a half, I mean I was falling asleep if I concentrated on something for an hour as it was…like I was absolutely wasted during these [video call] things.’(Trauma survivor, traumatic brain/neck injury)

‘I would have liked to have met my clients once face to face. I think it would have given me more idea of the context in which they lived and worked. And I do think it enhances the therapeutic relationship.’(OT05)

‘Learning, for me, is easier if you show me how to do it and then I’m straight onto practising to do it. But actually, because of [NHS Trust’s] rules, we were having to use DrDoctor [video call platform]. So, you kind of learn all this detail [previous software platform] and then go, right, anyway, park that because you’re doing DrDoctor, and that’s your only option.’(OT03)

‘Minimise the time and minimise the journey, minimise everything. Yes, in the end, the fact it brings it down to the comfort of your home, as long as you have the facilities within the home, it’s fine.’(Trauma survivor, orthopaedic injury)

‘The pros of being able to speak with someone online rather than having to travel is maximising people’s engagement that way. They just have to flick on a computer rather than get ready for a visit and all of that. There’s been no travel time, which is great.’(OT05)

Beliefs about Capabilities

‘I was concerned about not getting any objective feedback from people, any third-party feedback…in terms of sort of asking about, trying to be quite clear and saying what feedback are you getting from your employer and asking such questions like, how will you know if things aren’t going quite as well as you think.’(OT07)

‘If you’re purely by phone, it takes a bit longer to build that rapport with somebody than if you’ve seen them and they know who you are’(OT03)

‘So I would have liked to have met them once face-to-face, initially, I think, for my initial visit. But then I think it would have been—it was perfectly appropriate to carry out the rest of the intervention with my two patients over video.’(OT05)

‘And I think for him it’s been challenging to know, just quite how direct to be; and I think it’s possibly harder for that to come across virtually, that you don’t want to come across being like really assertive, and a sort of, well you’re wrong, I’m right type thing.’(OT07)

‘If [patient] was not on the ROWTATE study, I’d have been out to the home and gone, “Look, we [therapist and patient] can’t get on virtually. I’ve tried a number of times now. I’m just coming to your house. I want to see your bed mobility. I want to see your transfers. I want to see if there’s more I can get you doing in the kitchen”. We keep wasting chunks of time faffing about with trying to make a connection [online].’(OT03)

‘I think being able to see each other’s faces and gestures [on a video call] was certainly good.’(Trauma survivor, polytrauma)

‘So dealing with different levels of communication and cognition, it is easier if, visually, you can see someone. I can tell much more easily if you’re [patient] struggling and need extra processing time if I can see you than if you’re on the phone and you’re just not listening, or whether, actually, you’re [patient] struggling to process what I’m saying. That’s much easier visually. So yeah, I think if you can see them [patient] visually, it’s better.’(OT03)

Optimism

‘There’s something around people having a little bit more, it’s not necessarily respect, but give a little bit more importance perhaps to hospital appointments and face-to-face…there’s been the “could you not do a Saturday”…But then equally you think, well your consultant hasn’t offered you a Saturday appointment, you’d take time off to physically go to see them at hospital. So there’s something about giving it equal merit and weight I think, and an equal importance.’(OT07)

‘I think for most things, I actually prefer face-to-face interaction with people, just because I feel that it’s easier to engage with people on a more emotional level as well. It’s also, I think, easier, particularly if you’re very anxious about a situation, to then get support from someone in a meaningful way.’(Trauma survivor, polytrauma)

‘If I was going to go to a face-to-face meeting, I would’ve been conscious about my injuries, my parking, my walking, and all the other things. In that respect, remotely made life so easy.’(Trauma survivor, orthopaedic injury)

Social/Professional Role and Identity

‘Some of those work reviews and stuff that, traditionally, were done face-to-face and would’ve been time consuming. But to do them virtually, because you know the patient really well and you’ve done all the assessments that you need to do face-to-face, it works really well virtually.’(OT03)

‘I think the critical part for me is the contribution that theoccupational therapistsare making, in particular in that sort of knitting together…So, communicating and synthesising all of that advice, making those links, how they approach their employer as well, I think theoccupational therapistshave really just done a great job in connecting all of that up, and, I guess, connecting them up to psychology as well.’(CP06)

Acceptability of the Intervention

| TFA Construct | Summary of Key Findings | Therapists (Occupational Therapists and Clinical Psychologists) | Patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affective attitude | All patients were happy with remote delivery and grateful for the support they had received. All therapists felt the remote delivery of the intervention was acceptable. Many were concerned about building therapeutic rapport online; however, it was not affected for most, but it did take longer than it would face to face. | Well, I think there’ll be some people who will be really reticent. I think there are therapists who are really reticent to work this way and I’m sure there’ll be some patients for whom the idea is really off-putting and will say, “I’d rather that we do this all face-to-face.” I think in those cases, you would just try and say, “Well, let’s give it a go. We’ll test this out,” and try and orient them to that.’ (CP) ‘It was actually quite good to do the intervention remotely. It did work in this instance. My participants were both people who are capable of using technology. They had access to the internet. They were appropriately set up to do that.’ (OT) ‘The feedback from my participant one, from the HR manager was that they thought it was a really positive experience and described it as a luxury to have someone dedicated to supporting their employee back to work’ (OT) ‘What’s been really good is, across the two sites, to have that sense of we’re all feeling our way through this together, and I think you established that really early on with the original training and that was reinforced with the refresher training’ (CP) ‘But what has actually been quite positive is that they’ve managed to see my face the whole time and if I was doing face-to-face intervention, you have to obviously be wearing a mask [due to COVID-19].’ (OT) ‘I think there are therapists who are really reticent to work this way and I’m sure there’ll be some patients for whom the idea is really off-putting and will say, “I’d rather that we do this all face-to-face.”… I’m not sure that people who are that reticent to engage remotely would sign up for an intervention like this in the first place.’ (CP) | ‘It’s absolutely critical that the occupational therapists have time…I can’t emphasise enough how important it is to give more time to occupational therapists to help patients in this situation.’ (Trauma survivor, TBI) ‘I wasn’t expecting I was going to go back to work until six months, but because this OT was so adamant and created a strategy, it absolutely made a lot of difference to push me and, before my six months, I was happily doing six hours. I cannot be grateful more than that, I can tell you that, absolutely.’ (Trauma survivor, orthopaedic injury) |

| Burden | In some cases, trauma survivors preferred remote delivery to face-to-face sessions as it minimised travel, it was good to stay in the comfort of their home and it meant that sessions could be more flexible. Therapists stated that less time was wasted travelling to appointments and they were able to spend more time delivering rehabilitation. All felt remote delivery had minimal burden, with the only issues being increased workload if the therapist did not specialise in that injury type (e.g., neuro-OT working with orthopaedic trauma survivors) or extra time needed to familiarise themselves with technology. | ‘It’s so much easier because sometimes participants had to cancel at short notice, and rather than, well, we’ll have to wait for the next day that is allocated, we can sometimes pick up the day after, or later that day. You just have that flexibility that if you were travelling between appointments, you just wouldn’t have’ (CP) ‘It is an effort because, again, adding virtual just makes it something that’s less familiar, I guess, for me. So it is a bit more effortful.’ (OT) ‘I think it probably was the form filling. Once you’ve got your session up and running, you flow and it’s fine. I’m used to talking to somebody and writing notes, and that’s fine. I think it was the forms and checking have I got it right and how long do I spend on that.’ (CP) | “Absolutely great, because whether you see them personally or see them remotely, the way she made a difference in my life within the last few months through remote sessions is immensely high. I mean, if I was going to go to a face-to-face meeting, I would’ve been conscious about my injuries, my parking, my walking, and all the other things. In that respect, remotely made life so easy.” (Trauma survivor, orthopaedic injury) So yeah, all things being equal, perhaps in these cases of head injuries at the beginning when you still need a lot of time to sleep so that your body can recover, it may be beneficial, actually, to have contact online (Trauma survivor, TBI) ‘Minimise the time and minimise the journey, minimise everything. Yes, in the end, the fact it brings it down to the comfort of your home, as long as you have the facilities within the home, it’s fine. But if I had a choice because I have got my facilities, I would say, yes, I prefer a remote session’ (Trauma survivor, orthopaedic injury) |

| Ethicality | Most trauma survivors felt the therapist was on the ‘same page’ as them and shared the same values. Some therapists felt that remote intervention delivery fitted well with their new way of working as a result of COVID-19, and how their services would continue to deliver therapy via video or phone call post-pandemic, where possible. Therapists felt that the intervention fitted with their values and enabled them to deliver meaningful rehabilitation like VR, which is often time limited (or not possible) in normal clinical practice. | Absolutely in line. Yeah, absolutely, because it’s all around quality of life, meaningful activity, participation. Yeah, absolutely in line with what I do normally and what I kind of believe OT should be doing and should be able to look at and should be able to do for people. So yeah, absolutely in line with those values…I’ve really enjoyed the vocational rehab side of things because it’s so what OTs should be doing, in my eyes. It’s so about meaningful activity and positive mood, all those things that come with return to work. So yeah, definitely in line with my OT values. (OT) | ‘Absolutely, because she was on the same page. As soon as I talk about X, Y and Z, she’s on the same page as what I’m talking about. That made it a lot easier because…I can see it making a difference and it builds my confidence behind it.’ (Trauma survivor, orthopaedic injury) ‘She was so spot on with my issues and on the same page as I am. That made me more confident behind what she was telling me and just to take it on board at once.’ (Trauma survivor, orthopaedic injury) |

| Intervention coherence | All trauma survivors understood the need for VR as they felt they would have returned to work too soon without it. Therapists reported that trauma survivors had been receptive to the remote delivery and understood the purpose of the intervention, acting on therapists’ advice. All therapists understood the purpose of the intervention and knew how to deliver it, stating that training and mentoring was both necessary and helpful. | ‘I developed a good therapeutic relationship with them. I certainly think that they’ve understood the point of the intervention and they’ve both communicated benefiting from the intervention and feeling—particularly one participant saying she was really pleased she’d ticked the box that said, “Yes, I’ll have this intervention.’ (OT) ‘It is about the case management. It’s about linking in with other people that makes the difference. And from the other perspective, the employers have been mindful and aware of where they are in their journey, so they’ve got that information. Because sometimes, for example, patient three, the one that thought he would get back next week, it could have been a different employer that didn’t really have that understanding and then that expectation would be that he should be back. So, getting in early and just having those communications is good.’ (OT) | ‘It meant that I was able to understand my accident fully and to negotiate, together with someone who was very knowledgeable about what had happened to me, the best way back for me to fully recover. That meant that also my employer, I think, had huge benefits in terms of getting me back at every stage at the exact level I was able to work properly, but also knowing exactly how much time they ought to give me to recover fully.’ (Trauma survivor, TBI) ‘That is the right word, strategy. It’s step-by-step building up, and I can feel the difference. Why? Because my energy level wasn’t going down and I was just maintaining myself, happily maintaining my work. I’m doing six hours a day and happily doing it without losing my energy. So, when I come home, I have energy left to do other things as well. And it’s all down to the OT because she put the strategy behind it, and that works.’ (Trauma survivor, orthopaedic injury) ‘But in these situations, I think it’s all the more important to have someone like [OT] there to help you negotiate, and also to make the employer see that, in the end, it is for their benefit as well because they will get an employee back who is fully employable again and suffers less.’ (Trauma survivor, TBI) |

| Opportunity costs | Trauma survivors did not suggest that participating in the intervention had cost them anything in terms of time or money, with all referring to how much time and effort remote delivery had saved. Trauma survivors felt that the flexibility of the remote intervention and ability to rearrange therapy sessions last minute, meant that they did not have to give up anything (e.g., time and plans) to engage in the intervention. Only one therapist mentioned financial costs associated with delivering the intervention, as they decided to pay for an online videoconferencing software to deliver the intervention and had to use their own phone to call trauma survivors. | So just under £14 a month for my Zoom account. And money, printing costs, printing and paper costs, my phone, I’ve been using my own personal phone, and my own laptop and my own internet’ (OT) I think it has cost me time. It has cost me time. As I said, I’ve had to slot the ROWTATE in. Rather than it being a nice extra bit of work for me to do which I’d planned for, I’ve now had to slot it in to this demanding week. (CP) What was positive about it is that you can fit in sessions or interventions a lot more easily. They don’t take up as much time because they don’t involve travel. (OT) | ‘There’s been a few times where I’ve gone, “This is happening and I can’t speak to you then,” and it’s been quite last minute and they’ve gone, “Right, okay, we’ll rearrange it.” So they’ve always been flexible. It’s never cost me in time or money, at all.’ (Trauma survivor, orthopaedic injury) ‘So I can imagine if you’d have to travel, so where I live it takes me about 55 min to get to the [hospital] and back, so that would be two hours travelling…like that’s not like a small amount of time regardless who you are…so it’s been good being able to have this option rather than have to travel.’ (Trauma survivor, orthopaedic injury) |

| Perceived effectiveness | Trauma survivors did not feel online delivery affected the relationship they had with their therapist. Many noticed a difference in their ability to manage their RTW (e.g., taking regular breaks and managing their hours based on fatigue levels) as a result of the intervention and early contact to discuss RTW was important. All therapists felt they were able to deliver the intervention remotely and support their trauma survivor’s RTW. For most therapists, trauma survivors were confident using technology and had access to the internet, therefore were able to engage with the intervention. | I think it’s gone pretty well in terms of being able to engage people with the remote delivering and building up a rapport and a working relationship. I think that’s gone pretty well and we’ve been able to support people to make some changes remotely.’ (CP) ‘I feel quite positive about it because the feedback has been quite positive and people have said that they’re really glad they’re taking part in the study and they’re getting this additional support.’ (CP) ‘I would have liked to have met my clients once face to face. I think it would have given me more idea of the context in which they lived and worked. And I do think it enhances the therapeutic relationship.’ (OT) ‘It was actually quite good to do the intervention remotely. It did work in this instance. My participants were both people who are capable of using technology. They had access to the internet. They were appropriately set up to do that.’ (OT) | ‘The work with my occupational therapist, has been invaluable really, and absolutely amazing. [OT) has been very professional, very knowledgeable, and it has made my life so much easier having had that support. It was absolutely brilliant really.’ (Trauma survivor, orthopaedic injury) ‘I think it’s been brilliant. I think if I didn’t have it, I daren’t think where I’d be now. It’s been really helpful.’ (Trauma survivor, orthopaedic injury) ‘But then, also, when it came to negotiating with my employer what would be the best return to work for me, she was really invaluable as well. I think both for my employer and for myself, because she really made us understand what would be the best way to make me recovery fully and be back at work, eventually, in a full-time capacity, and sort of not to rush that.’ (Trauma survivor, TBI) |

| Self-efficacy | Trauma survivors felt their therapist had helped them to work towards goals and develop insight into the impact of their injury. One issue highlighted by therapists was difficulty gaining consent to speak to employers online, which meant parts of the intervention could not be delivered. Therapists that were initially apprehensive about remote delivery reported that they were now confident conducting sessions via video or phone call. | ‘Think the training was essential. I think it’s really important. Yeah, I think I would’ve tried to use my experience as best as I could for this, but I think I would’ve been kind of flailing a bit, going, oh, hold on a minute.’ (CP) ‘If there’s anything I’m not sure about from an intervention perspective, I would go back to [OT mentor] and be happy to kind of query that with her. And obviously we have the structured monthly mentoring with her, which has been sufficient in terms of when I’ve needed to ask things so far. But I would equally be happy to contact her if there was intervention stuff I wanted to ask in between times.’ (OT) ‘I think he’s [patient] been particularly interesting, and a particular challenge, which is good for me and I do like that type of patient and I can thrive on a challenge and I think it’s, you know, if I’m finding things a bit, you know, tricky, I will, you know, obviously you need to alter your approach don’t you depending on the client that you’re working with.’ (OT) ‘If anything, what it might force, and a big part of that, is promoting self-efficacy. I think when you’re doing it remotely, it really enables one way of thinking about it, because you do feel that much more removed and people know that you’re there and you can offer advice and you’re in contact. I don’t know what you’ll learn from the participants, but the feedback so far, kind of informally, seems somewhat positive about that. But it feels like you’re not alongside them in the same way as maybe you would be normally, and that leaves more to them, I think, or puts more on them.’ (CP) | ‘I think she’s been perfect. I couldn’t praise her any more, to be honest. She’s been a bit pushy sometimes, but in a good way, to push me to do stuff because, at the start, I wasn’t keen on doing anything, to be honest, because things were taking too long. It’s been, what, six months? It’s nearly seven months now. She’s pushed me and I feel like I’ve overtaken her expectations. So she’s helped me to push myself and now, yeah, I’m really chuffed, honestly.’ (Trauma survivor, orthopaedic injury) ‘I would also say, having been forced to really think about my work in itemised bits of tasks—although, that was something I was not very happy about when [OT] suggested I do it—was actually very helpful. And, in fact, I told that to a colleague of mine who was saying that she felt quite exhausted from the pandemic and all the home working. I told her about this exercise and she found that quite helpful, too.’ (Trauma survivor, TBI) ‘It’s an eye-opener regarding how to recover within myself within the working environment because the way I was going was probably the wrong way because I was going straight away into full hours working. She made me realise that if you’re going to have a lack of energy, you’re going to probably not wake up, or not going to come out of bed the next morning because you wear yourself out so quick. So that realisation was so good.’ (Trauma survivor, orthopaedic injury) ‘I think it changes your thinking about it and you can then be a bit more proactive with like how you do things, where you do things, when you do them, all that sort of stuff.’ (Trauma survivor, TBI) |

4. Discussion

Implications for Research and Practice

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Injuries and Violence: The Facts; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Feigin, V.L.; Feigin, V.L.; Nguyen, G.; Nguyen, G.; Cercy, K.; Cercy, K.; Johnson, C.O.; Johnson, C.O.; Alam, T.; Alam, T.; et al. Global, Regional, and Country-Specific Lifetime Risks of Stroke, 1990 and 2016. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2429–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Velzen, J.M.; Van Bennekom, C.A.M.; Edelaar, M.J.A.; Sluiter, J.K.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W. How many people return to work after acquired brain injury? A systematic review. Brain Inj. 2009, 23, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidal, I.B.; Huynh, T.K.; Biering-Sørensen, F. Return to work following spinal cord injury: A review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2007, 29, 1341–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, F.J.; Newstead, S.; McClure, R. A systematic review of early prognostic factors for return to work following acute orthopaedic trauma. Injury 2010, 41, 787–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escorpizo, R.; Reneman, M.F.; Ekholm, J.; Fritz, J.; Krupa, T.; Marnetoft, S.-U.; Maroun, C.E.; Guzman, J.R.; Suzuki, Y.; Stucki, G.; et al. A Conceptual Definition of Vocational Rehabilitation Based on the ICF: Building a Shared Global Model. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2011, 21, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donker-Cools, B.H.P.M.; Daams, J.G.; Wind, H.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W. Effective return-to-work interventions after acquired brain injury: A systematic review. Brain Inj. 2015, 30, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roels, E.H.; Aertgeerts, B.; Ramaekers, D.; Peers, K. Hospital- and community-based interventions enhancing (re)employment for people with spinal cord injury: A systematic review. Spinal Cord 2015, 54, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saltychev, M.; Eskola, M.; Tenovuo, O.; Laimi, K. Return to work after traumatic brain injury: Systematic review. Brain Inj. 2013, 27, 1516–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R.N.; Hogan, T.P.; Balbale, S.; Lones, K.; Goldstein, B.; Woo, C.; Smith, B.M. Sociotechnical Perspective on Implementing Clinical Video Telehealth for Veterans with Spinal Cord Injuries and Disorders. Telemed. e-Health 2017, 23, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, C.E.; Silverman, E.; Jia, H.; Geiss, M.; Omura, D. Effects of physical therapy delivery via home video telerehabilitation on functional and health-related quality of life outcomes. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2015, 52, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, G.A.; Judd, J.; Gray, M.A. The experience of medical and rehabilitation intervention for traumatic hand injuries in rural and remote North Queensland: A qualitative study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 37, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenforde, A.S.; Hefner, J.E.; Kodish-Wachs, J.E.; Iaccarino, M.A.; Paganoni, S. Telehealth in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: A Narrative Review. PM&R 2017, 9, S51–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettlewell, J.; Timmons, S.; Bridger, K.; Kendrick, D.; Kellezi, B.; Holmes, J.; Patel, P.; Radford, K. A study of mapping usual care and unmet need for vocational rehabilitation and psychological support following major trauma in five health districts in the UK. Clin. Rehabil. 2020, 35, 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, R.N.; Hogan, T.P.; Lones, K.; Balbale, S.; Scholten, J.; Bidelspach, D.; Musson, N.; Smith, B.M. Evaluation and Treatment of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury through the Implementation of Clinical Video Telehealth: Provider Perspectives from the Veterans Health Administration. PM&R 2016, 9, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M.; Dear, B.F.; Hush, J.M.; Titov, N.; Dean, C.M. myMoves Program: Feasibility and Acceptability Study of a Remotely Delivered Self-Management Program for Increasing Physical Activity among Adults with Acquired Brain Injury Living in the Community. Phys. Ther. 2016, 96, 1982–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johansson, B.; Rönnbäck, L. Novel computer tests for identification of mental fatigue after traumatic brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation 2015, 36, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.J.; Frymark, T.; Franceschini, N.M.; Theodoros, D.G. Assessment and Treatment of Cognition and Communication Skills in Adults with Acquired Brain Injury via Telepractice: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2015, 24, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fann, J.R.; Bombardier, C.H.; Vannoy, S.; Dyer, J.; Ludman, E.; Dikmen, S.; Marshall, K.; Barber, J.; Temkin, N. Telephone and In-Person Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Major Depression after Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Neurotrauma 2015, 32, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsaousides, T.; Spielman, L.; Kajankova, M.; Guetta, G.; Gordon, W.; Dams-O’Connor, K. Improving Emotion Regulation Following Web-Based Group Intervention for Individuals with Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2017, 32, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorstyn, D.; Roberts, R.; Murphy, G.; Craig, A.; Kneebone, I.; Stewart, P.; Chur-Hansen, A.; Marshall, R.; Clark, J.; Migliorini, C. Work and SCI: A pilot randomized controlled study of an online resource for job-seekers with spinal cord dysfunction. Spinal Cord 2018, 57, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheenen, M.E.; Visser-Keizer, A.C.; De Koning, M.E.; Van Der Horn, H.J.; Van De Sande, P.; Van Kessel, M.E.; Van Der Naalt, J.; Spikman, J.M. Cognitive Behavioral Intervention Compared to Telephone Counseling Early after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomized Trial. J. Neurotrauma 2017, 34, 2713–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Evald, L. Prospective memory rehabilitation using smartphones in patients with TBI: What do participants report? Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2014, 25, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiselev, J.; Haesner, M.; Gövercin, M.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E. Implementation of a Home-Based Interactive Training System for Fall Prevention: Requirements and Challenges. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2015, 41, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallon, B.; Houtstra, T. Telephone technology in social work group treatment. Health Soc. Work. 2007, 32, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solana, J.; Caceres, C.; Garcia-Molina, A.; Opisso, E.; Roig, T.; Tormos, J.M.; Gomez, E.J. Improving Brain Injury Cognitive Rehabilitation by Personalized Telerehabilitation Services: Guttmann Neuropersonal Trainer. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2014, 19, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kettlewell, J.; Phillips, J.; Radford, K.; Dasnair, R. Informing evaluation of a smartphone application for people with acquired brain injury: A stakeholder engagement study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2018, 18, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, T.; O’Neil-Pirozzi, T.; Morita, C. Clinician expectations for portable electronic devices as cognitive-behavioural orthoses in traumatic brain injury rehabilitation. Brain Inj. 2003, 17, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caffery, L.J.; Taylor, M.; North, J.B.; Smith, A. Tele-orthopaedics: A snapshot of services in Australia. J. Telemed. Telecare 2017, 23, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairy, D.; Lehoux, P.; Vincent, C. Exploring routine use of telemedicine through a case study in rehabilitation. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 2014, 35, 337–344. [Google Scholar]

- Rietdijk, R.; Power, E.; Attard, M.; Togher, L. Acceptability of telehealth-delivered rehabilitation: Experiences and perspectives of people with traumatic brain injury and their carers. J. Telemed. Telecare 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simic, T.; Leonard, C.; Laird, L.; Cupit, J.; Höbler, F.; Rochon, E. A Usability Study of Internet-Based Therapy for Naming Deficits in Aphasia. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2016, 25, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, J.R.; Pavliscsak, H.H.; Cooper, M.R.; Goldstein, L.A.; Fonda, S.J. Does Mobile Care (‘mCare’) Improve Quality of Life and Treatment Satisfaction among Service Members Rehabilitating in the Community? Results from a 36-Wk, Randomized Controlled Trial. Mil. Med. 2017, 183, e148–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kendrick, D.; das Nair, R.; Kellezi, B.; Morriss, R.; Kettlewell, J.; Holmes, J.; Timmons, S.; Bridger, K.; Patel, P.; Brooks, A.; et al. Vocational rehabilitation to enhance return to work after trauma (ROWTATE): Protocol for a non-randomised single-arm mixed-methods feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cane, J.; O’Connor, D.; Michie, S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sekhon, M.; Cartwright, M.; Francis, J.J. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spencer, L.; Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J.; Dillon, L. Quality in Qualitative Evaluation: A Framework for Assessing Research Evidence; Government Chief Social Researcher’s Office: London, UK, 2003.

- Ownsworth, T.; Theodoros, D.; Cahill, L.; Vaezipour, A.; Quinn, R.; Kendall, M.; Moyle, W.; Lucas, K. Perceived Usability and Acceptability of Videoconferencing for Delivering Community-Based Rehabilitation to Individuals with Acquired Brain Injury: A Qualitative Investigation. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2020, 26, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, C.; Atkins, J.; Baker, T.; Gonzales, E.; Paul, J.; Brooks, M. Factors influencing the adoption of telemedicine for treatment of military veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. J. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 50, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hale-Gallardo, J.L.; Kreider, C.M.; Jia, H.; Castaneda, G.; Freytes, I.M.; Ripley, D.C.C.; Ahonle, Z.J.; Findley, K.; Romero, S. Telerehabilitation for Rural Veterans: A Qualitative Assessment of Barriers and Facilitators to Implementation. J. Multidiscip. Health 2020, 13, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turgoose, D.; Ashwick, R.; Murphy, D. Systematic review of lessons learned from delivering tele-therapy to veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. J. Telemed. Telecare 2017, 24, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockway, J.A.; De Lore, J.S.; Ann, B.J.; Hart, T.; Hurst, S.; Fey-Hinckley, S.; Savage, J.; Warren, M.; Bell, K.R. Telephone-delivered problem-solving training after mild traumatic brain injury: Qualitative analysis of service members’ perceptions. Rehabil. Psychol. 2016, 61, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinger, P.; Hallam, K.; Fraser, D.; Pile, R.; Ardern, C.; Moreira, B.; Talbot, S. A novel web-support intervention to promote recovery following Anterior Cruciate Ligament reconstruction: A pilot randomised controlled trial. Phys. Ther. Sport 2017, 27, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, S.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.D.; Earis, D.; Titov, N.; Dear, B.F. Patient perspectives of Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for psychosocial issues post spinal cord injury. Rehabil. Psychol. 2019, 64, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feasibility Study Objectives | Methods to Address Objectives |

|---|---|

| 1. Adapt the ROWTATE intervention to make it suitable for remote delivery, as much as possible, via telerehabilitation and tele-psychology |

|

| 2. Adapt the ROWTATE occupational therapist and clinical psychologist training to make it suitable for remote delivery |

|

| 3. Assess acceptability, barriers and facilitators to remote delivery of the ROWTATE intervention via telerehabilitation and tele-psychology |

|

| Framework | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) | Affective attitude | How an individual feels about an intervention |

| Burden | The perceived amount of effort that is required to deliver or participate in the intervention | |

| Ethicality | The extent to which the intervention has good fit with an individual’s value system | |

| Intervention coherence | The extent to which the therapist or participant understands the intervention and how it works | |

| Opportunity costs | The extent to which benefits, profits or values must be given up to deliver or engage in the intervention | |

| Perceived effectiveness | The extent to which the intervention is perceived as likely to achieve its purpose | |

| Self-efficacy | The therapist’s or participant’s confidence that they can perform the behaviour(s) required to participate in the intervention | |

| Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) | Behavioural regulation | Anything aimed at managing or changing objectively observed or measured actions |

| Beliefs about capabilities | Acceptance of the truth, reality, or validity about an ability, talent, or facility that a person can put to constructive use | |

| Beliefs about consequences | Acceptance of the truth, reality, or validity about outcomes of a behaviour in a given situation | |

| Emotions | A complex reaction pattern, involving experiential, behavioural, and physiological elements, by which the individual attempts to deal with a personally significant matter or event | |

| Environmental context and resources | Any circumstance of a person’s situation or environment that discourages or encourages the development of skills and abilities, independence, social competence, and adaptive behaviour | |

| Goals | Mental representation of outcomes or end states that an individual wants to achieve | |

| Intentions | A conscious decision to perform a behaviour or a resolve to act in a certain way | |

| Knowledge | An awareness of the existence of something | |

| Memory, attention and decision processes | The ability to retain information, focus selectively on aspects of the environment, and choose between two or more alternatives | |

| Optimism | The confidence that things will happen for the best, or that desired goals will be attained | |

| Reinforcement | Increasing the probability of a response by arranging a dependent relationship, or contingency, between the response and a given stimulus | |

| Skills | An ability or proficiency acquired through practice | |

| Social influences | Those interpersonal processes that can cause an individual to change their thoughts, feelings, or behaviours | |

| Social-professional role and identity | A coherent set of behaviours and displayed personal qualities of an individual in a social or work setting |

| TDF Survey | Interview | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant ID | Profession | Years Experience | Specialist Area | VR Experience | Telerehab Experience | Pre-Training | Post-Training | Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention |

| OT01 | OT | 20+ | TBI, SCI | ||||||

| CP02 | CP | 15–19 | Stroke | ||||||

| OT03 | OT | 15–19 | TBI | ||||||

| OT04 | OT | 5–9 | Trauma | ||||||

| OT05 | OT | 20+ | TBI | ||||||

| CP06 | CP | 5–9 | ABI, neurological conditions | ||||||

| OT07 | OT | 15–19 | TBI | ||||||

| Participant ID | Age | Sex | ISS Score | Injury Type | Professional Industry | Size of Employing Organisation (Number of Employees) | Consent to Interview Employer? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P01 | 51 | Female | 16 | Polytrauma including TBI | Curator | 250+ | Yes Contact made but no response |

| P02 | 54 | Male | 9 | Orthopaedic | Gas engineer | Self-employed | NA Self-employed |

| P03 | 33 | Male | 9 | Head and neck injury, TBI | Recruitment consultant | 50–249 | No |

| P04 | 41 | Male | 9 | Orthopaedic | Lorry driver | 0–9 | No |

| Pre-Training (n = 7) | Post-Training (n = 4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDF Domain | Survey Statements | TDF Domain Mean (SD) | Question Mean (SD) | TDF Domain Mean (SD) | Question Mean (SD) |

| Intentions | 1. I intend to apply telerehabilitation protocols to each/every one of my patients’ sessions | 3.4 | 3.50 (0.50) | 5.42 | 5.50 (1.29) |

| 2. I will definitely apply telerehabilitation protocols to each/every one of my patients’ sessions | −0.23 | 3.14 (0.69) | −0.14 | 5.25 (1.50) | |

| 3. I have a strong intention to apply telerehabilitation protocols to each/every one of my patients’ sessions | 3.57 (0.53) | 5.50 (1.29) | |||

| Social influences | 1. People who are important to me think that I should deliver therapy using telerehabilitation | 5 | 4.29 (1.50) | 6 | 5.25 (0.96) |

| 2. People whose opinion I value would approve of me delivering therapy using telerehabilitation | −0.55 | 4.86 (0.90) | −0.5 | 6.25 (0.50) | |

| 3. I can count on support from colleagues whom I work with when things get tough with delivering therapy sessions using telerehabilitation | 5.43 (0.79) | 6.25 (0.50) | |||

| 4. Colleagues whom I work with are willing to listen to the problems I have when delivering therapy sessions using telerehabilitation | 5.43 (0.79) | 6.25 (0.50) | |||

| Knowledge | 1. I am aware of the content of an effective telerehabilitation programme | 5.03 | 4.57 (1.27) | 6.1 | 6.25 (0.50) |

| 2. I am aware of the objectives of a telerehabilitation programme | −0.34 | 5.00 (0.58) | −0.22 | 6.25 (0.50) | |

| 3. I know what my responsibilities are, with regard to delivering a therapy session using telerehabilitation | 5.29 (0.49) | 6.25 (0.50) | |||

| 4. I know how to use telerehabilitation | 4.86 (0.69) | 5.75 (0.50) | |||

| 5. I know when to use telerehabilitation | 5.43 (0.53) | 6.00 (0.82) | |||

| 1. I have received training regarding how to deliver telerehabilitation | 3.76 | 1.71 (0.76) | 5.92 | 6.00 (0.82) | |

| Skills | 2. I have the skills needed to deliver a telerehabilitation programme | −1.78 | 4.86 (0.69) | −0.38 | 5.50 (0.58) |

| 3. I have been able to practice using telerehabilitation | 4.71 (1.25) | 6.25 (0.50) | |||

| Memory, attention, and decision processes | 1. Using telerehabilitation to deliver each of my patients’ sessions is something I do automatically | 3.57 | 3.57 (0.79) | 4.75 | 4.75 (0.96) |

| 0 | −0.96 | ||||

| Social/professional role and identity | 1. Delivering therapy sessions using telerehabilitation is part of my role | 4.52 | 4.86 (0.69) | 6.33 | 6.75 (0.50) |

| 2. It is my responsibility to delivery therapy sessions using telerehabilitation protocols | −0.08 | 4.71 (1.25) | −0.38 | 6.25 (0.50) | |

| 3. Delivering therapy sessions using telerehabilitation is consistent with other aspects of my job | 4.43 (1.27) | 6.00 (1.41) | |||

| Beliefs about capabilities | 1. I am confident that I can plan and deliver therapy sessions with my patients using telerehabilitation protocols | 4.81 | 5.14 (0.90) | 5.54 | 6.00 (0.82) |

| 2. I am capable of planning and delivering telerehabilitation, even when little time is available | −0.45 | 5.00 (0.82) | −0.62 | 5.50 (1.00) | |

| 3. I have the confidence to plan and deliver therapy using telerehabilitation even when other professionals I work with are not doing this | 5.14 (0.90) | 5.75 (0.50) | |||

| 4. I have the confidence to plan and deliver therapy using telerehabilitation even when the patients who attend the service are not receptive | 4.57 (0.53) | 5.25 (0.50) | |||

| 5. I have personal control over planning and delivering therapy using telerehabilitation | 5.00 (1.00) | 6.25 (0.50) | |||

| 6. For me, planning and delivering therapy using telerehabilitation is easy | 4.00 (0.58) | 4.50 (1.00) | |||

| Optimism | 1. In uncertain times, when I plan and deliver therapy using telerehabilitation I usually expect that things will work out okay | 4.05 | 4.29 (0.76) | 5.08 | 5.50 (0.58) |

| 2. When I plan and deliver therapy using telerehabilitation, I feel optimistic about my job in the future | −0.3 | 4.14 (0.90) | −0.72 | 5.50 (0.58) | |

| 3. I do not expect anything will prevent me from using telerehabilitation to deliver therapy to my patients | 3.71 (1.60) | 4.25 (0.96) | |||

| Beliefs about consequences | 1. I believe delivering each of my patients’ sessions using telerehabilitation will lead to benefits for the patients who attend the service | 4.55 | 4.57 (1.27) | 5.75 | 5.75 (0.50) |

| 2. I believe delivering each of my patients’ sessions using telerehabilitation will benefit public health (i.e., health of the whole population) | −0.04 | 4.57 (0.79) | −0.41 | 5.25 (0.96) | |

| 3. In my view, using telerehabilitation to deliver each of my patients’ sessions is useful | 4.50 (0.76) | 5.75 (0.50) | |||

| 4. In my view, using telerehabilitation to deliver each of my patients’ sessions is worthwhile | 4.57 (0.79) | 6.25 (0.50) | |||

| Reinforcement | 1. I get recognition from management at the organisation where I work, when I use telerehabilitation to deliver my patients’ sessions | 4.38 | 4.13 (0.38) | 5.58 | 5.50 (1.00) |

| 2. When I use telerehabilitation to deliver my patients’ sessions, I get recognition from my colleagues | −0.22 | 4.43 (0.98) | −0.38 | 5.25 (0.98) | |

| 3. When I use telerehabilitation to deliver my patients’ sessions, I get recognition from those whom it impacts | 4.57 (1.13) | 6.00 (0.00) | |||

| Environmental context and resources | 1. In the organisation I work, all necessary resources are available to allow me to deliver my planned therapy using telerehabilitation | 3.79 | 2.43 (1.27) | 5.75 | 5.25 (0.50) |

| 2. I have support from the management of the organisation to deliver my planned therapy using telerehabilitation | −0.91 | 4.29 (1.60) | −0.47 | 6.25 (0.96) | |

| 3. The management of the organisation I work for are willing to listen to any problems I have when delivering my planned therapy using telerehabilitation | 4.86 (1.22) | 6.25 (0.50) | |||

| 4. The organisation I work for provides the opportunity for training to deliver my planned therapy using telerehabilitation | 3.50 (0.96) | 5.50 (1.73) | |||

| 5. The organisation I work for provides sufficient time for me to deliver my planned therapy using telerehabilitation | 3.86 (1.46) | 5.50 (0.58) | |||

| Goals | 1. Compared to my other tasks, planning how and delivering my therapy using telerehabilitation is a higher priority on my agenda | 4.76 | 4.86 (0.69) | 5 | 4.25 (1.71) |

| 2. Compared to my other tasks, planning how and delivering my therapy using telerehabilitation is an urgent item on my agenda | −0.3 | 4.43 (0.53) | −0.9 | 4.75 (0.96) | |

| 3. I have clear goals related to using telerehabilitation to deliver each of my patients’ sessions | 5.00 (1.00) | 6.00 (0.00) | |||

| Behavioural regulation | 1. I have a detailed plan of how I will deliver therapy using telerehabilitation | 4.37 | 4.14 (0.69) | 5.3 | 5.50 (0.58) |

| 2. I have a detailed plan of how I will deliver therapy using telerehabilitation when patients who usually attend the service are not receptive | −0.47 | 3.86 (0.69) | −0.41 | 4.75 (0.50) | |

| 3. I have a detailed plan of how I will deliver therapy using telerehabilitation when there is little time | 4.14 (0.69) | 5.00 (0.82) | |||

| 4. It is possible to adapt how I will deliver therapy using telerehabilitation to meet my needs as a rehabilitation therapist/psychologist | 4.71 (0.76) | 5.50 (0.58) | |||

| 5. Delivering therapy using telerehabilitation is compatible with other aspects of my job | 5.00 (0.93) | 5.75 (0.96) | |||

| Emotion | 1. I am able to deliver therapy using telerehabilitation without feeling anxious | 4.91 | 4.14 (1.22) | 5.58 | 5.50 (0.58) |

| 2. I am able to deliver therapy using telerehabilitation without feeling distressed or upset | −0.66 | 5.29 (0.76) | −0.14 | 5.75 (0.50) | |

| 3. I am able to deliver therapy using telerehabilitation, even when I feel stressed | 5.29 (0.49) | 5.50 (1.00) | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kettlewell, J.; Lindley, R.; Radford, K.; Patel, P.; Bridger, K.; Kellezi, B.; Timmons, S.; Andrews, I.; Fallon, S.; Lannin, N.; et al. Factors Affecting the Delivery and Acceptability of the ROWTATE Telehealth Vocational Rehabilitation Intervention for Traumatic Injury Survivors: A Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9744. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189744

Kettlewell J, Lindley R, Radford K, Patel P, Bridger K, Kellezi B, Timmons S, Andrews I, Fallon S, Lannin N, et al. Factors Affecting the Delivery and Acceptability of the ROWTATE Telehealth Vocational Rehabilitation Intervention for Traumatic Injury Survivors: A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9744. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189744

Chicago/Turabian StyleKettlewell, Jade, Rebecca Lindley, Kate Radford, Priya Patel, Kay Bridger, Blerina Kellezi, Stephen Timmons, Isabel Andrews, Stephen Fallon, Natasha Lannin, and et al. 2021. "Factors Affecting the Delivery and Acceptability of the ROWTATE Telehealth Vocational Rehabilitation Intervention for Traumatic Injury Survivors: A Mixed-Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9744. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189744

APA StyleKettlewell, J., Lindley, R., Radford, K., Patel, P., Bridger, K., Kellezi, B., Timmons, S., Andrews, I., Fallon, S., Lannin, N., Holmes, J., Kendrick, D., & Team, o. b. o. t. R. (2021). Factors Affecting the Delivery and Acceptability of the ROWTATE Telehealth Vocational Rehabilitation Intervention for Traumatic Injury Survivors: A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9744. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189744