Relationship between Bullying Victimization and Quality of Life in Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Taiwan: Mediation of the Effects of Emotional Problems and ADHD and Oppositional Defiant Symptoms

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Bullying Victimization and Its Association with Quality of Life

1.2. Mediating Role of Emotional Problems

1.3. Mediating Roles of ADHD and Oppositional Defiant Disorder Symptoms

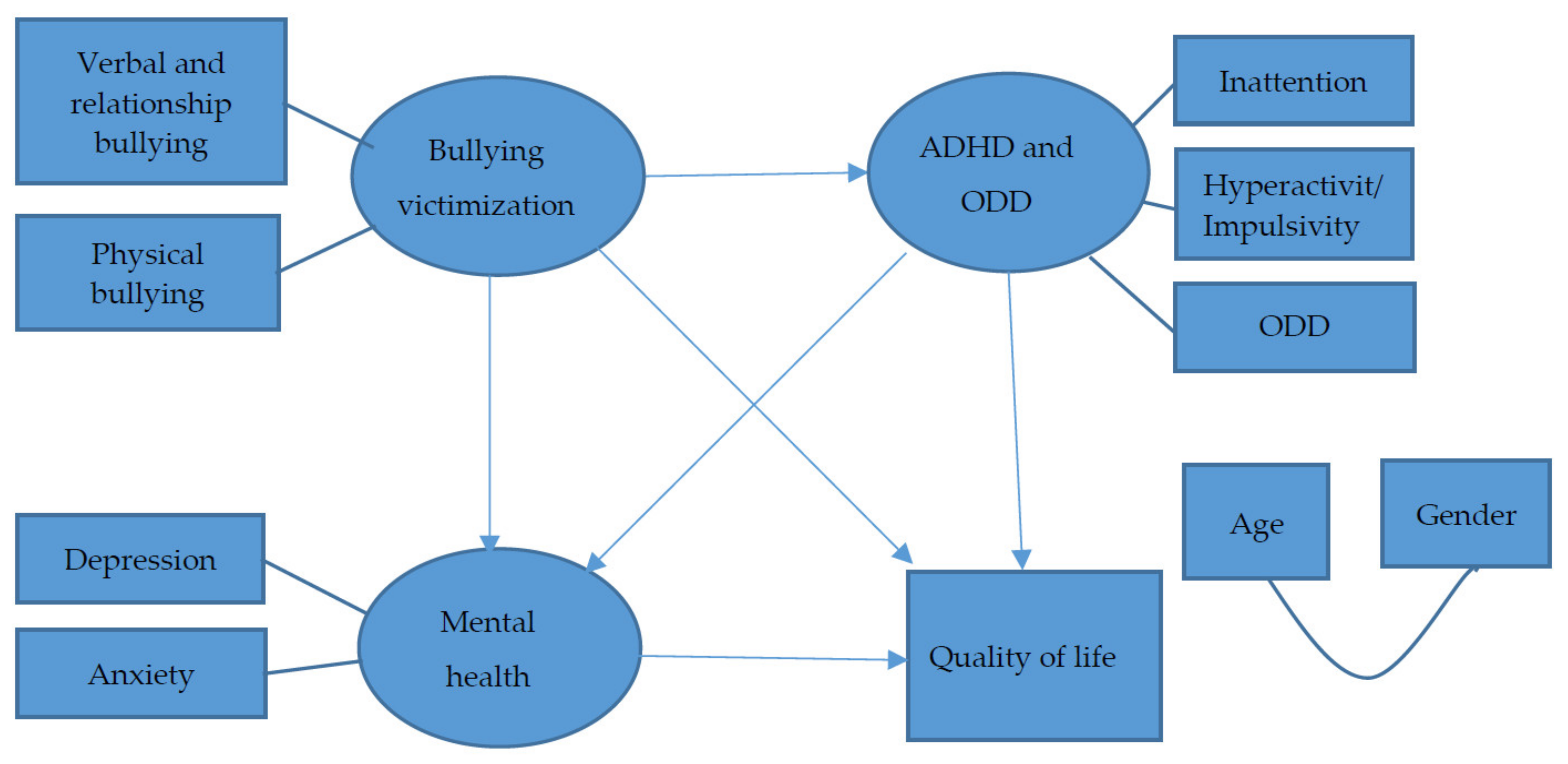

1.4. Aims of This Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Bullying Victimization

2.2.2. QoL

2.2.3. Emotional Problems

2.2.4. ADHD and ODD Symptoms

2.3. Procedure and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Correlation Matrices

3.2. Full Model

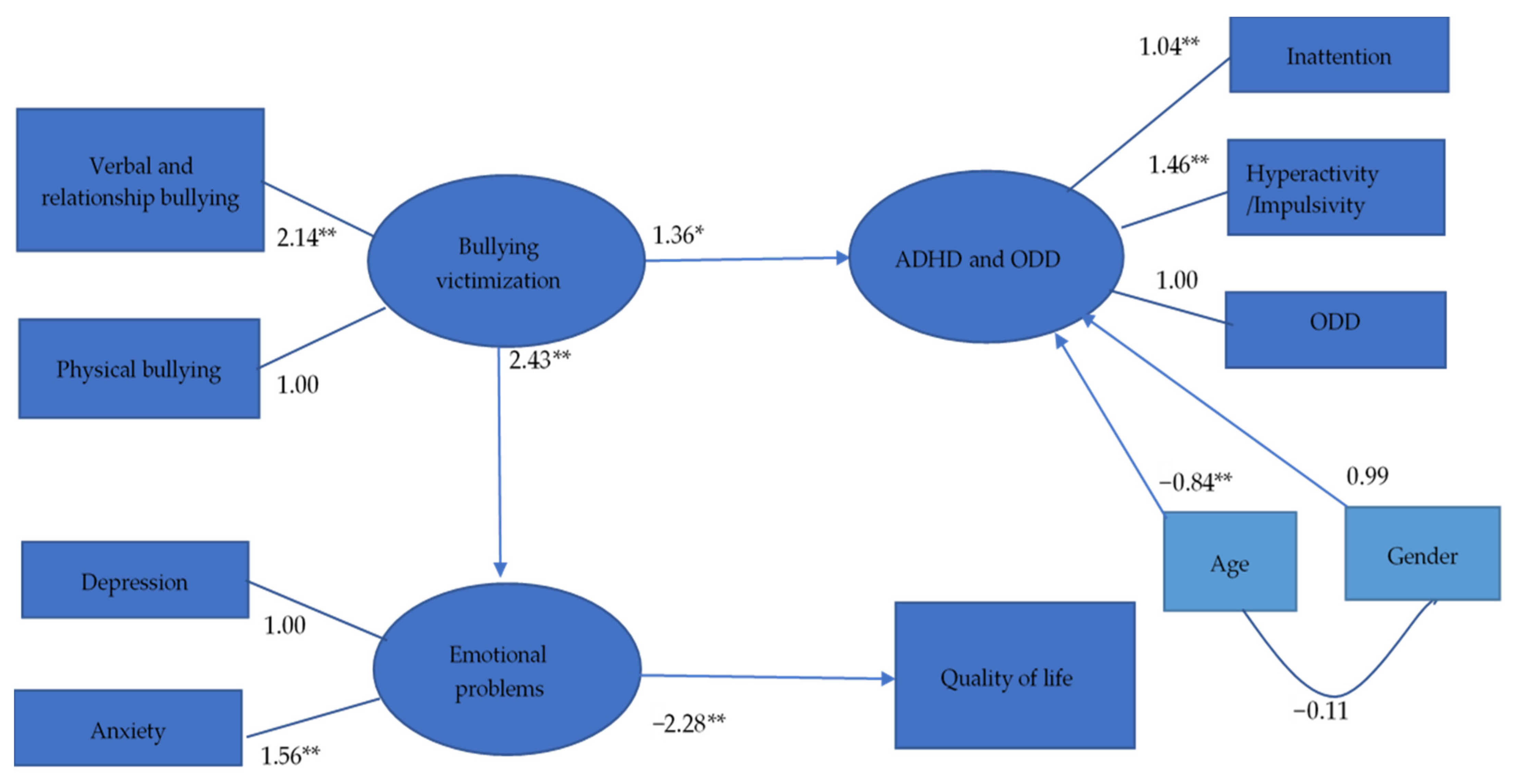

3.3. Reduced Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Association of Bullying Victimization with QoL and Mediating Effect of Emotional Problems

4.2. Mediating Effect of ADHD and ODD Symptoms

4.3. Implications

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nansel, T.R.; Overpeck, M.; Pilla, R.S.; Ruan, W.J.; Simons-Morton, B.; Scheidt, P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA 2001, 285, 2094–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wolke, D.; Woods, S.; Bloomfield, L.; Karstadt, L. The association between direct and relational bullying and behaviour problems among primary school children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2000, 41, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camodeca, M.; Goossens, F.A. Aggression, social cognitions, anger and sadness in bullies and victims. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2005, 46, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D.; Solberg, M.E.; Breivik, K. Long-term school-level effects of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP). Scand. J. Psychol. 2020, 61, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. Victimization by peers: Antecedents and long-term outcomes. In Social Withdrawal, Inhibition, and Shyness in Children; Rubin, K., Asendorf, J.B., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 315–341. [Google Scholar]

- Haraldstad, K.; Kvarme, L.G.; Christophersen, K.-A.; Helseth, S. Associations between self-efficacy, bullying and health-related quality of life in a school sample of adolescents: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hidalgo-Rasmussen, C.; Molina, T.; Molina, R.; Sepúlveda, R.; Martinez, V.; Montaño, R.; González, E.; George, M. Influence of bullying on the quality of life perception of Chilean students. Rev. Med. Chil. 2015, 143, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chester, K.L.; Spencer, N.H.; Whiting, L.; Brooks, F.M. Association between experiencing relational bullying and adolescent health-related quality of life. J. Sch. Health 2017, 87, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wilkins-Shurmer, A.; O’Callaghan, M.J.; Najman, J.; Bor, W.; Williams, G.; Anderson, M.J. Association of bullying with adolescent health-related quality of life. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2003, 39, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beckman, L.; Svensson, M.; Frisén, A. Preference-based health-related quality of life among victims of bullying. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadiroğlu, T.; Hendekci, A.; Tosun, Ö. Investigation of the relationship between peer victimization and quality of life in school-age adolescents. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 32, 850–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Whoqol Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, R.; Sanders, S.; Doust, J.; Beller, E.; Glasziou, P. Prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2015, 135, e994–e1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Willcutt, E.G. The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analytic review. Neurotherapeutics 2012, 9, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Erskine, H.E.; Norman, R.E.; Ferrari, A.; Chan, G.; Copeland, W.E.; Whiteford, H.; Scott, J. Long-term outcomes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmberg, K.; Hjern, A. Bullying and attention-deficit- hyperactivity disorder in 10-year-olds in a Swedish community. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2008, 50, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumpulainen, K.; Räsänen, E.; Henttonen, I.; Almqvist, F.; Kresanov, K.; Linna, S.-L.; Moilanen, I.; Piha, J.; Puura, K.; Tamminen, T. Bullying and psychiatric symptoms among elementary school-age children. Child Abuse Negl. 1998, 22, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.-F.; Yang, P.; Wang, P.-W.; Lin, H.-C.; Liu, T.-L.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Tang, T.-C. Association between school bullying levels/types and mental health problems among Taiwanese adolescents. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.-J.; Stewart, R.; Kim, J.-M.; Kim, S.-W.; Shin, I.-S.; Dewey, M.E.; Maskey, S.; Yoon, J.-S. Differences in predictors of traditional and cyber-bullying: A 2-year longitudinal study in Korean school children. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 22, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unnever, J.D.; Cornell, D.G. Bullying, self-control, and ADHD. J. Interpers. Violence 2003, 18, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twyman, K.A.; Saylor, C.F.; Saia, D.; Macias, M.M.; Taylor, L.A.; Spratt, E. Bullying and ostracism experiences in children with special health care needs. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2010, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmermanis, V.; Wiener, J. Social correlates of bullying in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2011, 26, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örengül, A.C.; Goker, H.; Zorlu, A.; Gormez, V.; Soylu, N. Peer victimization in preadolescent children with ADHD in Turkey. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 36, NP6624–NP6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.K.; O’Donnell, L.; Stueve, A.; Coulter, R. Cyberbullying, school bullying, and psychological distress: A regional census of high school students. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysing, M.; Askeland, K.G.; La Greca, A.M.; Solberg, M.E.; Breivik, K.; Sivertsen, B. Bullying involvement in adolescence: Implications for sleep, mental health, and academic outcomes. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 886260519853409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nansel, T.R.; Craig, W.; Overpeck, M.D.; Saluja, G.; Ruan, W.J. Cross-national consistency in the relationship between bullying behaviors and psychosocial adjustment. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seals, D.; Young, J. Bullying and victimization: Prevalence and relationship to gender, grade level, ethnicity, self-esteem, and depression. Adolescence 2003, 38, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carlyle, K.E.; Steinman, K.J. Demographic differences in the prevalence, co-occurrence, and correlates of adolescent bullying at school. J. Sch. Health 2007, 77, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltiala-Heino, R.; Rimpelä, M.; Rantanen, P.; Rimpelä, A. Bullying at school—An indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. J. Adolesc. 2000, 23, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, G.; James, A.; Smith, D.M. Bullying in schools: Self reported anxiety, depression, and self esteem in secondary school children. BMJ 1998, 317, 924–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kumpulainen, K.; Räsänen, E. Children involved in bullying at elementary school age: Their psychiatric symptoms and deviance in adolescence: An epidemiological sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2000, 24, 1567–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. Bullying at school: Long-terms outcomes for the victims and an effective school-based intervention program. In Aggressive Behavior: Current Perspectives; Huesmann, L.R., Ed.; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994; pp. 97–130. [Google Scholar]

- Sourander, A.; Jensen, P.; Ronning, J.A.; Niemelä, S.; Helenius, H.; Sillanmäki, L.; Kumpulainen, K.; Piha, J.; Tamminen, T.; Moilanen, I.; et al. What is the early adulthood outcome of boys who bully or are bullied in childhood? The Finnish “From a Boy to a Man” study. Pediatrics 2007, 120, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sourander, A.; Jensen, P.; Rönning, J.A.; Elonheimo, H.; Niemelä, S.; Helenius, H.; Kumpulainen, K.; Piha, J.; Tamminen, T.; Moilanen, I.; et al. Childhood bullies and victims and their risk of criminality in late adolescence: The Finnish “From a Boy to a Man” study. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arseneault, L.; Walsh, E.; Trzesniewski, K.; Newcombe, R.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T. Bullying victimization uniquely contributes to adjustment problems in young children: A nationally representative cohort study. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanish, L.D.; Guerra, N.G. A longitudinal analysis of patterns of adjustment following peer victimization. Dev. Psychopathol. 2002, 14, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, G.W.; Troop-Gordon, W. The role of chronic peer difficulties in the development of children’s psychological adjustment problems. Child Dev. 2003, 74, 1344–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, L.; Carlin, J.; Thomas, L.; Rubin, K.; Patton, G. Does bullying cause emotional problems? A prospective study of young teenagers. BMJ 2001, 323, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becker, S.P.; Mehari, K.R.; Langberg, J.M.; Evans, S.W. Rates of peer victimization in young adolescents with ADHD and associations with internalizing symptoms and self-esteem. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.; Lycett, K.; Hiscock, H.; Care, E.; Sciberras, E. Longitudinal associations between internalizing and externalizing comorbidities and functional outcomes for children with ADHD. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2015, 46, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.-N.; Tai, Y.-M.; Yang, L.-K.; Gau, S.S.-F. Prediction of childhood ADHD symptoms to quality of life in young adults: Adult ADHD and anxiety/depression as mediators. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 3168–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gini, G. Associations between bullying behaviour, psychosomatic complaints, emotional and behavioural problems. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2008, 44, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado-Gracia, J.; Mundo-Cid, P.; Lopez-Seco, F.; Acosta-García, S.; Ruiz, M.J.C.; Vilella, E.; Masana-Marín, A. Lifetime victimization in children and adolescents with ADHD. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 36, NP3241–NP3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klassen, A.F.; Miller, A.; Fine, S. Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents who have a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 2004, 114, e541–e547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Matza, L.S.; Rentz, A.M.; Secnik, K.; Swensen, A.R.; Revicki, D.A.; Michelson, D.; Spencer, T.; Newcorn, J.; Kratochvil, C.J. The link between health-related quality of life and clinical symptoms among children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2004, 25, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, D.F.; Steeber, J.; McBurnett, K. A review of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder complicated by symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2010, 31, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhne, M.; Schachar, R.; Tannock, R. Impact of comorbid oppositional or conduct problems on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 1715–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biederman, J.; Newcorn, J.; Sprich, S. Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 1991, 148, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gau, S.S.-F.; Ni, H.-C.; Shang, C.-Y.; Soong, W.-T.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Lin, L.-Y.; Chiu, Y.-N. Psychiatric comorbidity among children and adolescents with and without persistent attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2010, 44, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliszka, S.R. Comorbidity of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with psychiatric disorder: An overview. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1998, 59, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murphy, K.; Barkley, R.A. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder adults: Comorbidities and adaptive impairments. Compr. Psychiatry 1996, 37, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Y.-M.; Gau, C.-S.; Gau, S.S.-F.; Chiu, H.-W. Prediction of ADHD to anxiety disorders: An 11-year national insurance data analysis in Taiwan. J. Atten. Disord. 2012, 17, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, D.V.; Sheehan, K.H.; Shytle, R.D.; Janavs, J.; Bannon, Y.; Rogers, J.E.; Milo, K.M.; Stock, S.L.; Wilkinson, B. Reliability and validity of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview for child and adolescents (MINI-KID). J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 71, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.-F.; Kim, Y.-S.; Tang, T.-C.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Cheng, C.-P. Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Chinese version of the School Bullying Experience Questionnaire. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2012, 28, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, S.H. Manual of the Children Depressive Inventory—Taiwan Version; Psychological Publishing Co.: Taipei, Taiwan, 2008. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fuh, J.-L.; Wang, S.-J.; Lu, S.-R.; Juang, K.-D. Assessing quality of life for adolescents in Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2005, 59, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, M. Children’s Depression Inventory; Multi-Health Systems: North Tonawanda, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- March, J.S. Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; Multi-Health Systems: North Tonawanda, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Yen, C.-F.; Yang, P.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Hsu, F.-C.; Cheng, C.-P. Factor structure, reliability and validity of the Taiwanese version of the multidimensional anxiety scale for children. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2010, 41, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gau, S.S.-F.; Shang, C.-Y.; Liu, S.-K.; Lin, C.-H.; Swanson, J.M.; Liu, Y.-C.; Tu, C.-L. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham, version IV scale—Parent form. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2008, 17, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, J.M.; Kraemer, H.C.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Arnold, L.E.; Conners, C.K.; Abikoff, H.B.; Clevenger, W.; Davies, M.; Elliott, G.R.; Greenhill, L.L.; et al. Clinical relevance of the primary findings of the MTA: Success rates based on severity of ADHD and ODD symptoms at the end of treatment. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language; Scientific Software International: Lincolnwood, IL, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-89498-033-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P. Structural equation modelling: Adjudging model fit. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.-C.; Huang, M.-F.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Hu, H.-F.; Yen, C.-F. Pain, bullying involvement, and mental health problems among children and adolescents with ADHD in Taiwan. J. Atten. Disord. 2019, 23, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.-F.; Chou, W.-J.; Yen, C.-F. Anxiety and depression among adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: The roles of behavioral temperamental traits, comorbid autism spectrum disorder, and bullying involvement. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2016, 32, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Finan, P.H.; Smith, M.T. The comorbidity of insomnia, chronic pain, and depression: Dopamine as a putative mechanism. Sleep Med. Rev. 2013, 17, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Humphreys, K.L.; Zeanah, C.H. Deviations from the expectable environment in early childhood and emerging psychopathology. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015, 40, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Garner, A.S.; Siegel, B.S.; Dobbins, M.I.; Earls, M.F.; McGuinn, L.; Pascoe, J.; Wood, D.L. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2011, 129, e232–e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teicher, M.H.; Samson, J.A. Childhood maltreatment and psychopathology: A case for ecophenotypic variants as clinically and neurobiologically distinct subtypes. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 1114–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, W.-J.; Liu, T.-L.; Yang, P.; Yen, C.-F.; Hu, H.-F. Bullying victimization and perpetration and their correlates in adolescents clinically diagnosed with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2018, 22, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K.; Monks, C.P. Concepts of bullying: Developmental and cultural aspects. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2008, 20, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n (%)/Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 36 (21.1) | - | 0.18 * | 0.02 | 0.18 * | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.14 | −0.18 * | 0.14 |

| 2. | 14 (1.48) | - | −0.14 | −0.32 ** | −0.16 * | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.08 | −0.10 | |

| 3. | 15.62 (5.70) | - | 0.67 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.17 * | 0.12 | −0.05 | 0.16 * | −0.19 * | ||

| 4. | 9.66 (6.38) | - | 0.59 ** | 0.16 * | 0.07 | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.08 | |||

| 5. | 11.98 (6.15) | - | 0.14 | 0.07 | −0.08 | 0.17 * | −0.23 ** | ||||

| 6. | 2.44 (2.50) | - | 0.35 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.38 ** | −0.31 ** | |||||

| 7. | 0.91 (1.41) | - | 0.25 ** | 0.36 * | −0.29 ** | ||||||

| 8. | 35.59 (18.08) | - | 0.54 ** | −0.46 ** | |||||||

| 9. | 15.56 (7.64) | - | −0.72 ** | ||||||||

| 10. | 131.53 (20.03) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, C.-W.; Lee, K.-H.; Hsiao, R.C.; Chou, W.-J.; Yen, C.-F. Relationship between Bullying Victimization and Quality of Life in Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Taiwan: Mediation of the Effects of Emotional Problems and ADHD and Oppositional Defiant Symptoms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189470

Lin C-W, Lee K-H, Hsiao RC, Chou W-J, Yen C-F. Relationship between Bullying Victimization and Quality of Life in Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Taiwan: Mediation of the Effects of Emotional Problems and ADHD and Oppositional Defiant Symptoms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189470

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Chien-Wen, Kun-Hua Lee, Ray C. Hsiao, Wen-Jiun Chou, and Cheng-Fang Yen. 2021. "Relationship between Bullying Victimization and Quality of Life in Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Taiwan: Mediation of the Effects of Emotional Problems and ADHD and Oppositional Defiant Symptoms" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189470

APA StyleLin, C.-W., Lee, K.-H., Hsiao, R. C., Chou, W.-J., & Yen, C.-F. (2021). Relationship between Bullying Victimization and Quality of Life in Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Taiwan: Mediation of the Effects of Emotional Problems and ADHD and Oppositional Defiant Symptoms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189470