Lifestyle in Undergraduate Students and Demographically Matched Controls during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Sampling and Recruitment

2.4. Outcome Variable

2.5. Variables and Measurements

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Lifestyle Behaviours and Mental Health

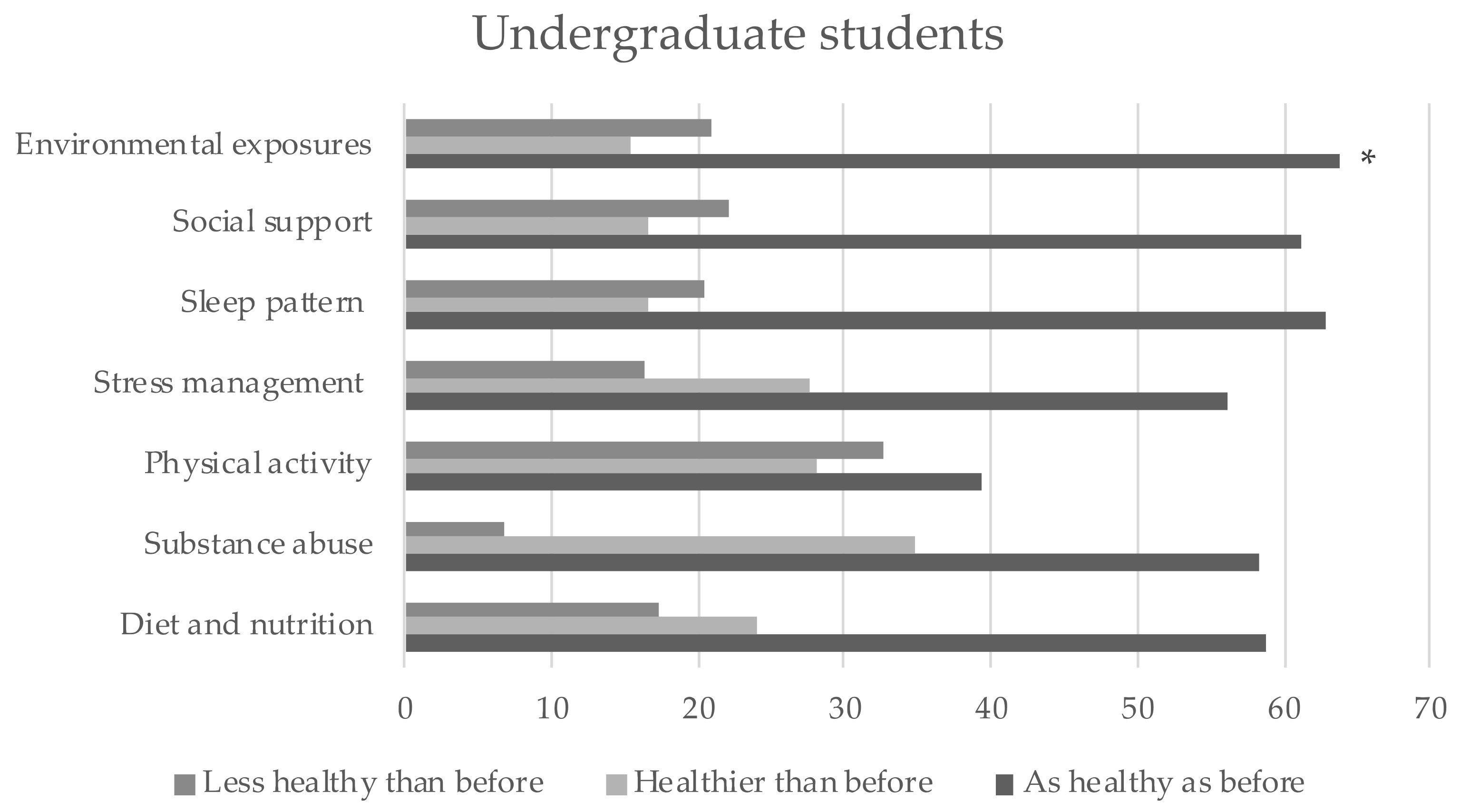

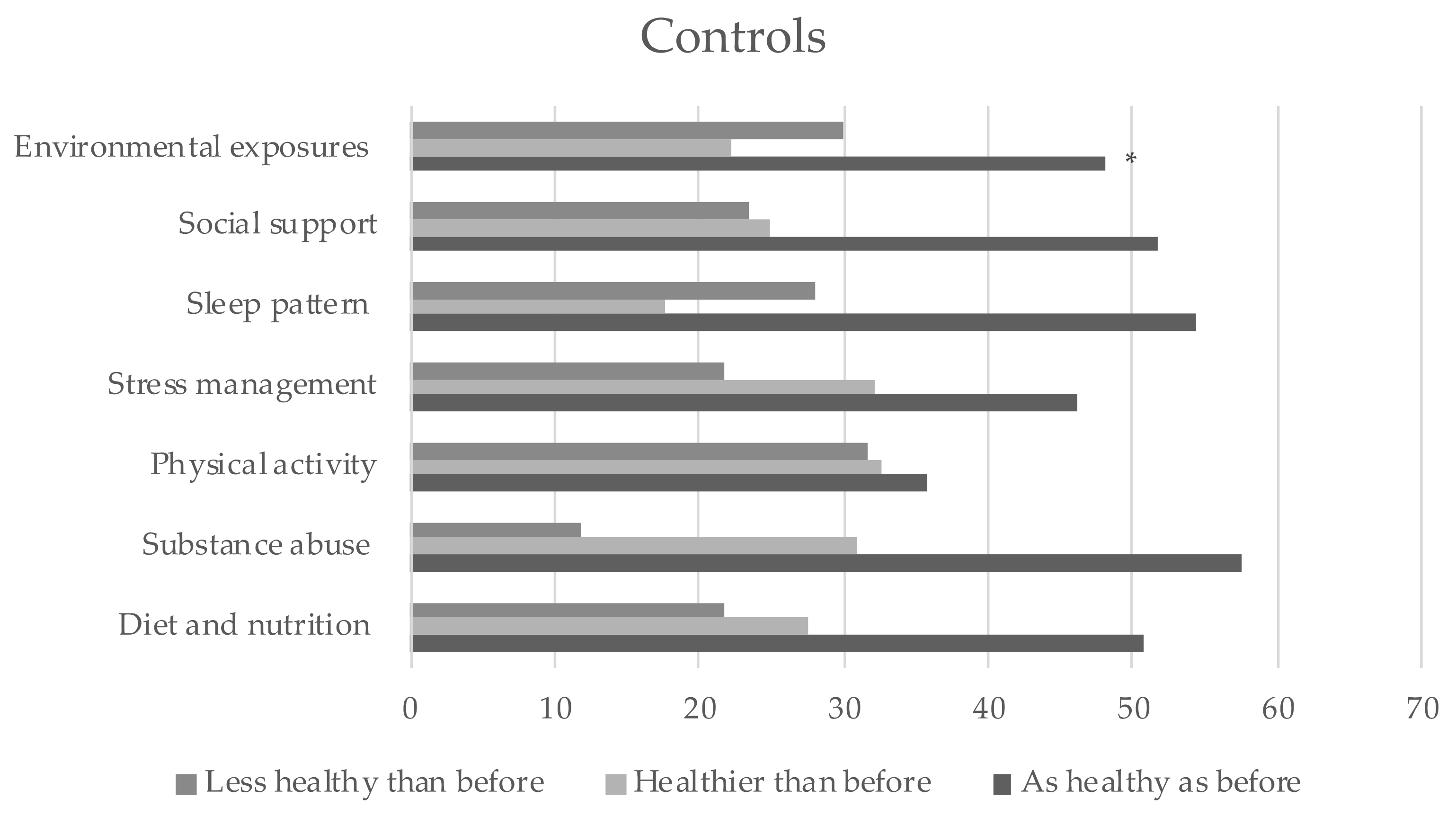

3.2. Changes on Lifestyle Behaviours during the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.3. Variables Independently Associated with Lifestyle Behaviours

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balanzá-Martínez, V.; Atienza-Carbonell, B.; Kapczinski, F.; de Boni, R.B. Lifestyle Behaviours during the COVID-19—Time to Connect. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2020, 141, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, V.; Lönn, A.; Ekblom, B.; Kallings, L.V.; Väisänen, D.; Hemmingsson, E.; Andersson, G.; Wallin, P.; Stenling, A.; Ekblom, Ö.; et al. Lifestyle Habits and Mental Health in Light of the Two Covid-19 Pandemic Waves in Sweden, 2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Lifestyle Medicine Organization. What Is Lifestyle Medicine?—The European Lifestyle Medicine Organization. Available online: https://www.eulm.org/what-is-lifestyle-medicine (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Stanaway, J.D.; Afshin, A.; Gakidou, E.; Lim, S.S.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Comparative Risk Assessment of 84 Behavioural, Environmental and Occupational, and Metabolic Risks or Clusters of Risks for 195 Countries and Territories, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1923–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nyberg, S.T.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Pentti, J.; Madsen, I.E.H.; Sabia, S.; Alfredsson, L.; Bjorner, J.B.; Borritz, M.; Burr, H.; Goldberg, M.; et al. Association of Healthy Lifestyle with Years Lived without Major Chronic Diseases. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 760–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Firth, J.; Siddiqi, N.; Koyanagi, A.; Siskind, D.; Rosenbaum, S.; Galletly, C.; Allan, S.; Caneo, C.; Carney, R.; Carvalho, A.F.; et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: A Blueprint for Protecting Physical Health in People with Mental Illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 675–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banks, S.; Dinges, D.F. Behavioral and Physiological Consequences of Sleep Restriction. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2007, 3, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez-Ojeda, M.A.; de Luna-Bertos, E.; De, E.; Bertos, L. Hábitos de Vida Saludable En La Población Universitaria. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 31, 1910–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallè, F.; Veshi, A.; Sabella, E.A.; Çitozi, M.; da Molin, G.; Ferracuti, S.; Liguori, G.; Orsi, G.B.; Napoli, C.; Napoli, C. Awareness and Behaviors Regarding COVID-19 among Albanian Undergraduates. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goweda, R.A.; Hassan-Hussein, A.; Alqahtani, M.A.; Janaini, M.M.; Alzahrani, A.H.; Sindy, B.M.; Alharbi, M.M.; Kalantan, S.A. Prevalence of Sleep Disorders among Medical Students of Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Public Health Res. 2020, 9, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, M.J.; Hennis, P.J.; Magistro, D.; Donaldson, J.; Healy, L.C.; James, R.M. Nine Months into the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Study Showing Mental Health and Movement Behaviours Are Impaired in UK Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallè, F.; Sabella, E.A.; Ferracuti, S.; de Giglio, O.; Caggiano, G.; Protano, C.; Valeriani, F.; Parisi, E.A.; Valerio, G.; Liguori, G.; et al. Sedentary Behaviors and Physical Activity of Italian Undergraduate Students during Lockdown at the Time of CoViD−19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Larrad, A.; Mañas, A.; Labayen, I.; González-Gross, M.; Espin, A.; Aznar, S.; Serrano-Sánchez, J.A.; Vera-Garcia, F.J.; González-Lamuño, D.; Ara, I.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Confinement on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour in Spanish University Students: Role of Gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, P.K.; Lawler, S.; Durham, J.; Cullerton, K. The Food Choices of US University Students during COVID-19. Appetite 2021, 161, 105130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragun, R.; Veček, N.N.; Marendić, M.; Pribisalić, A.; Đivić, G.; Cena, H.; Polašek, O.; Kolčić, I. Have Lifestyle Habits and Psychological Well-Being Changed among Adolescents and Medical Students Due to COVID-19 Lockdown in Croatia? Nutrients 2020, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, H.; Buck, C.; Stock, C.; Zeeb, H.; Pischke, C.R.; Fialho, P.M.M.; Wendt, C.; Helmer, S.M. Engagement in Health Risk Behaviours before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in German University Students: Results of a Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Guo, S.; Wu, P.; Lu, Q.; Xu, Y.; Liu, L.; Su, S.; Shi, L.; Que, J.; et al. Association of Symptoms of Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity with Problematic Internet Use among University Students in Wuhan, China During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 286, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego-Gómez, J.I.; Campillo-Cano, M.; Carrión-Martínez, A.; Balanza, S.; Rodríguez-González-Moro, M.T.; Simonelli-Muñoz, A.J.; Rivera-Caravaca, J.M. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Impact on Homebound Nursing Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieta, E.; Pérez, V.; Arango, C. Psychiatry in the aftermath of COVID-19. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud. Ment. 2020, 13, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aylie, N.S.; Mekonen, M.A.; Mekuria, R.M. The Psychological Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic among University Students in Bench-Sheko Zone, South-West Ethiopia: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balanzá-Martínez, V.; Kapczinski, F.; de Azevedo Cardoso, T.; Atienza-Carbonell, B.; Rosa, A.R.; Mota, J.C.; de Boni, R.B. The Assessment of Lifestyle Changes during the COVID-19 Pandemic Using a Multidimensional Scale. Revista de Psiquiatria y Salud Mental 2021, 14, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boni, R.B.; Balanzá-Martínez, V.; Mota, J.C.; de Azevedo Cardoso, T.; Ballester, P.; Atienza-Carbonell, B.; Bastos, F.I.; Kapczinski, F. Depression, Anxiety, and Lifestyle among Essential Workers: A Web Survey from Brazil and Spain during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Med. Care 2003, 41, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bush, K.; Kivlahan, D.R.; McDonell, M.B.; Fihn, S.D.; Bradley, K.A. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998, 158, 1789–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yamashita, T.; Kunkel, S.R. An International Comparison of the Association among Literacy, Education, and Health across the United States, Canada, Switzerland, Italy, Norway, and Bermuda: Implications for Health Disparities. J. Health Commun. 2015, 20, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Duong, T.; Pham, K.M.; Do, B.N.; Kim, G.B.; Dam, H.T.B.; Le, V.-T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Nguyen, H.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Le, T.T.; et al. Digital Healthy Diet Literacy and Self-Perceived Eating Behavior Change during COVID-19 Pandemic among Undergraduate Nursing and Medical Students: A Rapid Online Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Facorro, B. Mental Health and the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Revista de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental 2020, 13, 55–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Álvarez, L.; de la Fuente-Tomás, L.; García-Portilla, M.P.; Sáiz, P.A.; Lacasa, C.M.; Santo, F.D.; González-Blanco, L.; Bobes-Bascarán, M.T.; García, M.V.; Vázquez, C.Á.; et al. Early Psychological Impact of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic and Lockdown in a Large Spanish Sample. J. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasheras, I.; Gracia-García, P.; Lipnicki, D.M.; Bueno-Notivol, J.; López-Antón, R.; de la Cámara, C.; Lobo, A.; Santabárbara, J. Prevalence of Anxiety in Medical Students during the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Rapid Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, R.P.; Mortier, P.; Bruffaerts, R.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Ebert, D.D.; Green, J.G.; Hasking, P.; et al. WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and Distribution of Mental Disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2018, 127, 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Blanco, C.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Onieva-Zafra, M.D.; Parra-Fernández, M.L.; Prado-Laguna, M.C.; Hernández-Martínez, A. Physical Activity and Sedentary Lifestyle in University Students: Changes during Confinement Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, C.; Ghazi, H.; Georgiou, I. The Mental Health and Well-Being Benefits of Exercise during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study of Medical Students and Newly Qualified Doctors in the UK. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Monshed, A.H.; El-Adl, A.A.; Ali, A.S.; Loutfy, A. University Students under Lockdown, the Psychosocial Effects and Coping Strategies during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross Sectional Study in Egypt. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwer, K.R.; Walmsley, L.A.; Parrish, E.M.; McCubbin, A.K.; Braido, C.E.C.; Okoli, C.T.C. Examining the Associations between Self-Care Practices and Psychological Distress among Nursing Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaudias, V.; Zerhouni, O.; Pereira, B.; Cherpitel, C.J.; Boudesseul, J.; de Chazeron, I.; Romo, L.; Guillaume, S.; Samalin, L.; Cabe, J.; et al. The Early Impact of the COVID-19 Lockdown on Stress and Addictive Behaviors in an Alcohol-Consuming Student Population in France. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 628631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, M.H.E.M.; Larson, L.R.; Sharaievska, I.; Rigolon, A.; McAnirlin, O.; Mullenbach, L.; Cloutier, S.; Vu, T.M.; Thomsen, J.; Reigner, N.; et al. Psychological Impacts from COVID-19 among University Students: Risk Factors across Seven States in the United States. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Goldberg, S.B.; Lin, D.; Qiao, S.; Operario, D. Psychiatric Symptoms, Risk, and Protective Factors among University Students in Quarantine during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, H.R.; Stevens, A.K.; Hayes, K.; Jackson, K.M. Changes in Alcohol Consumption among College Students Due to Covid-19: Effects of Campus Closure and Residential Change. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2020, 81, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galasso, V.; Pons, V.; Profeta, P.; Becher, M.; Brouard, S.; Foucault, M. Gender Differences in COVID-19 Attitudes and Behavior: Panel Evidence from Eight Countries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 27285–27291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzek, D.; Skolmowska, D.; Głabska, D. Analysis of Gender-Dependent Personal Protective Behaviors in a National Sample: Polish Adolescents’ Covid-19 Experience (Place-19) Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prowse, R.; Sherratt, F.; Abizaid, A.; Gabrys, R.L.; Hellemans, K.G.C.; Patterson, Z.R.; McQuaid, R.J. Coping With the COVID-19 Pandemic: Examining Gender Differences in Stress and Mental Health Among University Students. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 650759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saguem, B.N.; Nakhli, J.; Romdhane, I.; Nasr, S.B. Predictors of Sleep Quality in Medical Students during COVID-19 Confinement. L’Encéphale 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, L.; Pastorino, R.; Molinari, E.; Anelli, F.; Ricciardi, W.; Graffigna, G.; Boccia, S. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Psychological Well-Being of Students in an Italian University: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, R.K.; Baral, S.; Khatri, E.; Pandey, S.; Pandeya, P.; Neupane, R.; Yadav, D.K.; Marahatta, S.B.; Kaphle, H.P.; Poudyal, J.K.; et al. Anxiety and Depression Among Health Sciences Students in Home Quarantine During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Selected Provinces of Nepal. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 580561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornili, M.; Petri, D.; Berrocal, C.; Fiorentino, G.; Ricceri, F.; Macciotta, A.; Bruno, A.; Farinella, D.; Baccini, M.; Severi, G.; et al. Psychological Distress in the Academic Population and Its Association with Socio-Demographic and Lifestyle Characteristics during COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown: Results from a Large Multicenter Italian Study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslan, I.; Ochnik, D.; Çınar, O. Exploring Perceived Stress among Students in Turkey during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, J.; Ward, P.B.; Stubbs, B. Editorial: Lifestyle Psychiatry. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scotta, A.V.; Cortez, M.V.; Miranda, A.R. Insomnia Is Associated with Worry, Cognitive Avoidance and Low Academic Engagement in Argentinian University Students during the COVID-19 Social Isolation. Psychol. Health Med. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheletti Cremasco, M.; Mulasso, A.; Moroni, A.; Testa, A.; Degan, R.; Rainoldi, A.; Rabaglietti, E. Relation among Perceived Weight Change, Sedentary Activities and Sleep Quality during COVID-19 Lockdown: A Study in an Academic Community in Northern Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subdirección General de Actividad Universitaria Investigadora de la Secretaría General de Universidades. Datos y Cifras Del Sistema Universitario Español. Publicación 2020–2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.universidades.gob.es/stfls/universidades/Estadisticas/ficheros/Datos_y_Cifras_2020-21.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (National Statistics Institute). Población Residente Por Fecha, Sexo y Edad. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dynt3/inebase/es/index.htm?padre=1894&capsel=1895 (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Instituto Nacional de Evaluación Educativa. Panorama de la Educación Indicadores de la OCDE 2019; Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes, J. Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used? An experiment using 5-point, 7-point and 10-point scales. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 50, 61–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, J.T.; Weston, R.; Voyles, E.C. Stuck in the Middle: The Use and Interpretation of Mid-Points in Items on Questionnaires. J. Gen. Psychol. 2015, 142, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, R. The Mid-Point on a Rating Scale: Is It Desirable? Mark. Bull. 1991, 2, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Controls | Undergraduate Students | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | SMILE-C Mean (SD)/r | p-Value | n (%) | SMILE-C Mean (SD)/r | p-Value | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 59 (26.70) | 76.85 (7.25) | 0.449 | 59 (26.70) | 80.95 (9.33) | 0.086 |

| Female | 162 (73.30) | 77.34 (8.68) | 162 (73.30) | 79.4 (7.65) | ||

| Age * | 23 (21–25) | r = 0.076 | 0.259 | 22 (21–23) | r = −0.002 | 0.979 |

| Number of cohabitants * | 3.0 (2.5–4.0) | r = 0.129 | 0.056 | 4.0 (3.0–4.0) | r = 0.108 | 0.109 |

| COVID−19 diagnosis | ||||||

| No | 203 (91.90) | 76.99 (8.32) | 0.101 | 209 (94.57) | 79.58 (8.13) | 0.132 |

| Yes | 18 (8.10) | 79.67 (8.06) | 12 (5.43) | 83.83 (7.47) | ||

| Lost somebody in the pandemic | ||||||

| No | 204 (92.30) | 77.25 (8.14) | 0.591 | 202 (91.40) | 79.8 (8.02) | 0.817 |

| Yes | 17 (7.70) | 76.64 (10.40) | 19 (8.60) | 80.0 (9.57) | ||

| Economic difficulties during the pandemic | ||||||

| No | 151 (68.30) | 79.09 (6.93) | <0.001 | 179 (81.00) | 80.88 (7.36) | 0.005 |

| Yes | 58 (26.20) | 73.74 (8.89) | 28 (12.67) | 75.18 (8.33) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 12 (5.40) | 70.33 (12.44) | 14 (6.33) | 75.5 (12.43) | ||

| Self-rated health | ||||||

| Very good or good | 176 (79.64) | 79.19 (6.78) | <0.001 | 192 (86.88) | 81.12 (7.16) | <0.001 |

| Regular, bad or very bad | 45 (20.36) | 69.47 (9.24) | 29 (13.12) | 71.17 (9.03) | ||

| Diagnosed or treated for mental illness during the last year | ||||||

| No | 176 (79.64) | 78.36 (7.74) | <0.001 | 175 (79.18) | 81.01 (7.53) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 45 (20.36) | 72.69 (8.99) | 46 (20.81) | 75.28 (8.86) | ||

| Screening for depression and anxiety | ||||||

| Negative for both depression and anxiety | 123 (55.66) | 80.17 (6.90) | <0.001 | 142 (64.25) | 82.94 (6.90) | <0.001 |

| Positive for depression only | 16 (7.24) | 75.12 (6.56) | 16 (7.24) | 74.18 (6.36) | ||

| Positive for anxiety only | 30 (13.57) | 75.43 (5.97) | 15 (6.79) | 78.6 (6.43) | ||

| Positive for both depression and anxiety | 52 (23.53) | 71.86 (9.89) | 48 (21.72) | 72.83 (7.20) | ||

| Screening for alcohol abuse | ||||||

| Negative | 184 (83.26) | 77.47 (8.11) | 0.541 | 188 (85.07) | 79.79 (8.25) | 0.978 |

| Positive | 37 (16.74) | 75.92 (9.27) | 33 (14.93) | 79.94 (7.59) | ||

| Diagnosed or treated for schizophrenia/bipolar disorder/anorexia/bulimia in the previous year | ||||||

| No | 214 (96.83) | 77.51 (7.97) | 0.036 | 216 (97.73) | 79.82 (8.16) | 0.977 |

| Yes | 7 (3.17) | 68.0 (13.19) | 5 (2.62) | 79.40 (8.08) | ||

| Diagnosed or treated for diabetes in the previous year | ||||||

| No | 212 (95.93) | 77.39 (8.31) | 0.088 | 217 (98.20) | 79.83 (8.10) | 0.893 |

| Yes | 9 (4.07) | 72.89 (7.47) | 4 (1.80) | 78.75 (11.44) | ||

| Diagnosed or treated for asthma/bronchitis in the previous year | ||||||

| No | 205 (92.76) | 77.26 (8.42) | 0.483 | 207 (93.70) | 79.77 (8.23) | 0.836 |

| Yes | 16 (7.24) | 76.56 (7.01) | 14 (6.30) | 80.50 (6.97) | ||

| Diagnosed or treated for heart disease or hypertension in the previous year | ||||||

| No | 211 (95.47) | 77.21 (8.41) | 0.929 | 218 (98.60) | 79.79 (8.15) | 0.585 |

| Yes | 10 (4.53) | 77.20 (6.30) | 3 (1.40) | 81.67 (9.29) | ||

| Diagnosed or treated for chronic disease in the previous year | ||||||

| No | 179 (81.00) | 77.61 (8.62) | 0.044 | 185 (83.71) | 79.87 (8.17) | 0.977 |

| Yes | 42 (19.00) | 75.5 (6.66) | 36 (16.29) | 79.53 (8.10) | ||

| Diagnosed or treated for others (HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, cancer, cirrhosis, kidney disease, other) | ||||||

| No | 192 (86.88) | 77.69 (7.91) | 0.061 | 192 (86.88) | 79.98 (7.84) | 0.669 |

| Yes | 29 (13.12) | 74.00 (10.15) | 29 (13.12) | 78.68 (9.98) | ||

| Variables | Controls n (%) | Undergraduate Students n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening of alcohol abuse | |||

| Negative | 184 (83.3) | 188 (85.1) | 0.093 |

| Positive | 37 (16.7) | 33 (14.9) | |

| Screening of depression | |||

| Negative | 153 (69.2) | 157 (71.0) | 0.077 |

| Positive | 68 (30.8) | 64 (29.0) | |

| Screening of anxiety | |||

| Negative | 139 (62.9) | 158 (71.5) | 0.042 |

| Positive | 82 (37.1) | 63 (28.5) | |

| Lifestyle changes: | |||

| Diet and nutrition | |||

| Mild/no changes | 156 (70.6) | 178 (80.5) | 0.018 |

| Totally/moderate changes | 65 (29.4) | 43 (19.5) | |

| Substance abuse | |||

| Mild/no changes | 178 (80.5) | 189 (85.5) | 0.228 |

| Totally/moderate changes | 43 (19.5) | 32 (14.5) | |

| Physical activity | |||

| Mild/no changes | 112 (50.7) | 120 (54.3) | 0.497 |

| Totally/moderate changes | 109 (49.3) | 101 (45.7) | |

| Stress management | |||

| Mild/no changes | 139 (62.9) | 154 (69.7) | 0.137 |

| Totally/moderate changes | 82 (37.1) | 67 (30.3) | |

| Restorative sleep | |||

| Mild/no changes | 153 (69.2) | 176 (79.6) | 0.022 |

| Totally/moderate changes | 68 (30.8) | 45 (20.4) | |

| Social support | |||

| Mild/no changes | 144 (65.2) | 161 (72.9) | 0.111 |

| Totally/moderate changes | 77 (34.8) | 60 (27.1) | |

| Environmental exposures | |||

| Mild/no changes | 137 (62.0) | 156 (70.6) | 0.078 |

| Totally/moderate changes | 84 (38.0) | 65 (29.4) | |

| Variables | Controls n (%) | Undergraduate Students n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diet and nutrition | |||

| As healthy as before | 112 (50.7) | 130 (58.8) | 0.216 |

| Healthier than before | 61 (27.6) | 53 (24.0) | |

| Less healthy than before | 48 (21.7) | 38 (17.2) | |

| Substance abuse | |||

| As healthy as before | 127 (57.5) | 129 (58.4) | 0.172 |

| Healthier than before | 68 (30.8) | 77 (34.8) | |

| Less healthy than before | 26 (11.8) | 15 (6.8) | |

| Physical activity | |||

| As healthy as before | 79 (35.7) | 87 (39.4) | 0.56 |

| Healthier than before | 72 (32.6) | 62 (28.1) | |

| Less healthy than before | 70 (31.7) | 72 (32.6) | |

| Stress management | |||

| As healthy as before | 102 (46.2) | 124 (56.1) | 0.1 |

| Healthier than before | 71 (32.1) | 61 (27.6) | |

| Less healthy than before | 48 (21.7) | 36 (16.3) | |

| Restorative sleep | |||

| As healthy as before | 120 (54.3) | 139 (62.9) | 0.126 |

| Healthier than before | 39 (17.6) | 37 (16.7) | |

| Less healthy than before | 62 (28.1) | 45 (20.4) | |

| Social support | |||

| As healthy as before | 114 (51.6) | 135 (61.1) | 0.068 |

| Healthier than before | 55 (24.9) | 37 (16.7) | |

| Less healthy than before | 52 (23.5) | 49 (22.2) | |

| Environmental exposures | |||

| As healthy as before | 106 (48.0) | 141 (63.8) | 0.004 |

| Healthier than before | 49 (22.2) | 34 (15.4) | |

| Less healthy than before | 66 (29.9) | 46 (20.8) | |

| Variables | Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| B CI (95%) | p-Value | |

| Number of cohabitants | 1.057 (0.195–1.919) | 0.017 |

| Self-rated health | ||

| Very good or good | Reference | |

| Regular, poor or very poor | −7.674 (−10.045–5.304) | <0.001 |

| Screening for depression and anxiety | ||

| Negative for both anxiety and depression | Reference | |

| Positive for depression only | −3.958 (−7.531–0.385) | 0.03 |

| Positive for anxiety only | −3.679 (−6.425–0.934) | 0.009 |

| Positive for both depression and anxiety | −5.626 (−8.002–3.25) | <0.001 |

| Substance abuse | ||

| Mild/no changes | Reference | |

| Totally/moderate changes | −2.422 (−4.759–0.085) | 0.042 |

| Stress management | ||

| Mild/no changes | Reference | |

| Totally/moderate changes | 3.010 (1.140–4.881) | 0.002 |

| Variables | Undergraduate Students | |

|---|---|---|

| B CI (95%) | p-Value | |

| Number of cohabitants | 1.101 (0.249–1.953) | 0.012 |

| Self-rated health | ||

| Very good or Good | Reference | |

| Regular, bad or very bad | −5.729 (−8.494–2.964) | <0.001 |

| Screening for depression and anxiety | ||

| Negative for both anxiety and depression | Reference | |

| Positive for depression only | −7.575 (−10.921–4.230) | <0.001 |

| Positive for anxiety only | −2.890 (−6.382–0.603) | 0.104 |

| Positive for both depression and anxiety | −7.341 (−9.677–5.006) | <0.001 |

| Diagnosed or treated for a mental illness in the previous year | ||

| No | Reference | |

| Yes | −2.379 (−4.632–0.127) | 0.039 |

| Economic difficulties during the pandemic | ||

| No | Reference | |

| Yes | −2.665 (−5.325–0.004) | 0.050 |

| Prefer not to respond | −3.932 (−7.485–0.379) | 0.030 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giner-Murillo, M.; Atienza-Carbonell, B.; Cervera-Martínez, J.; Bobes-Bascarán, T.; Crespo-Facorro, B.; De Boni, R.B.; Esteban, C.; García-Portilla, M.P.; Gomes-da-Costa, S.; González-Pinto, A.; et al. Lifestyle in Undergraduate Students and Demographically Matched Controls during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8133. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158133

Giner-Murillo M, Atienza-Carbonell B, Cervera-Martínez J, Bobes-Bascarán T, Crespo-Facorro B, De Boni RB, Esteban C, García-Portilla MP, Gomes-da-Costa S, González-Pinto A, et al. Lifestyle in Undergraduate Students and Demographically Matched Controls during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(15):8133. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158133

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiner-Murillo, María, Beatriz Atienza-Carbonell, Jose Cervera-Martínez, Teresa Bobes-Bascarán, Benedicto Crespo-Facorro, Raquel B. De Boni, Cristina Esteban, María Paz García-Portilla, Susana Gomes-da-Costa, Ana González-Pinto, and et al. 2021. "Lifestyle in Undergraduate Students and Demographically Matched Controls during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 15: 8133. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158133

APA StyleGiner-Murillo, M., Atienza-Carbonell, B., Cervera-Martínez, J., Bobes-Bascarán, T., Crespo-Facorro, B., De Boni, R. B., Esteban, C., García-Portilla, M. P., Gomes-da-Costa, S., González-Pinto, A., Jaén-Moreno, M. J., Kapczinski, F., Ponce-Mora, A., Sarramea, F., Tabarés-Seisdedos, R., Vieta, E., Zorrilla, I., & Balanzá-Martínez, V. (2021). Lifestyle in Undergraduate Students and Demographically Matched Controls during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 8133. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158133