Factors Associated with Influenza Vaccination Uptake among U.S. Adults: Focus on Nativity and Race/Ethnicity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

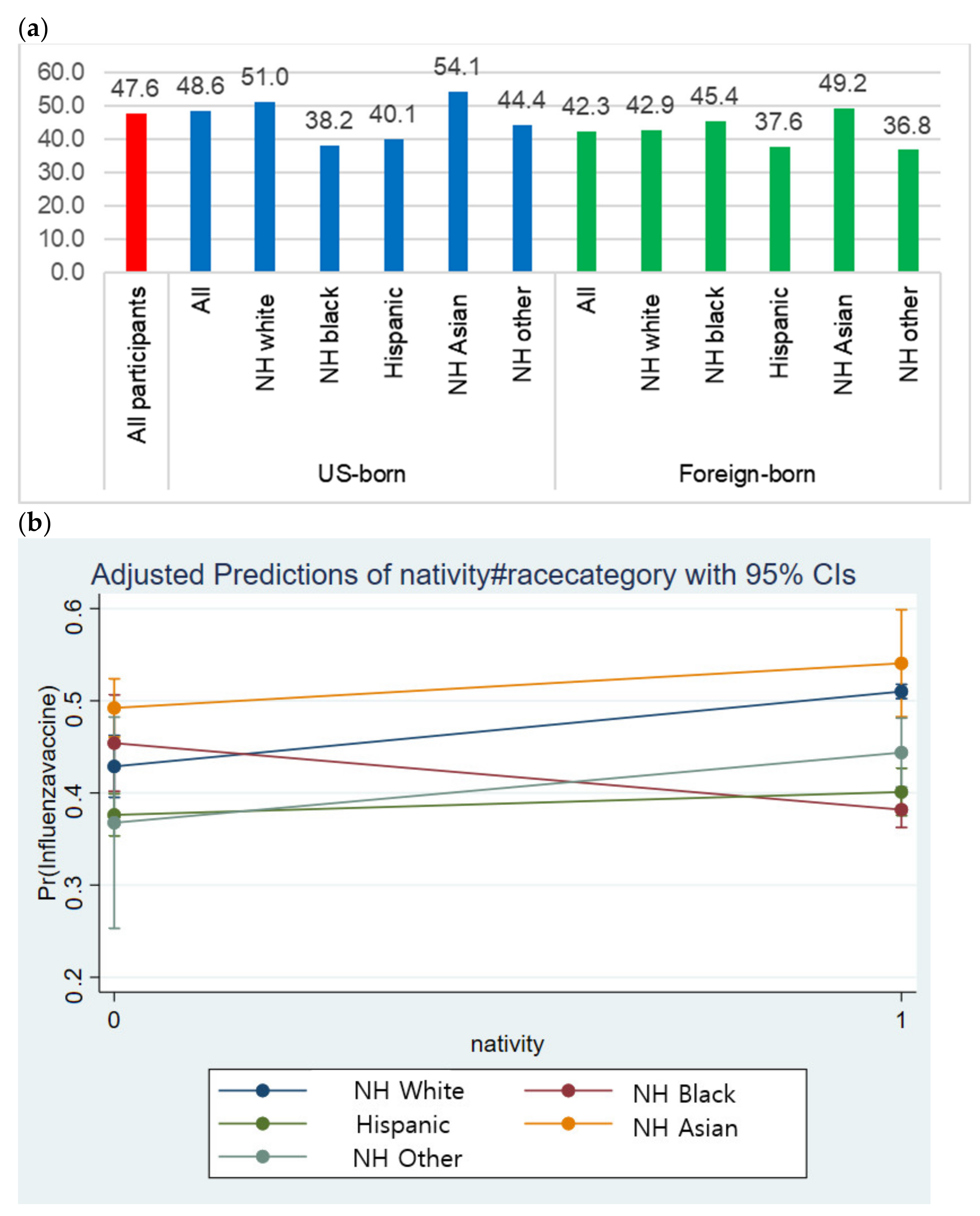

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Past Seasons Estimated Influenza Disease Burden. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/past-seasons.html (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Domnich, A.; Cambiaggi, M.; Vasco, A.; Maraniello, L.; Ansaldi, F.; Baldo, V.; Bonanni, P.; Calabrò, G.E.; Costantino, C.; de Waure, C.; et al. Attitudes and Beliefs on Influenza Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from a Representative Italian Survey. Vaccines 2020, 8, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Influenza Burden of Disease. Available online: https://www.who.int/influenza/surveillance_monitoring/bod/en/ (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Disease Burden of Influenza. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Up to 650,000 People Die of Respiratory Diseases Linked to Seasonal Flu Each Year. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/13-12-2017-up-to-650-000-people-die-of-respiratory-diseases-linked-to-seasonal-flu-each-year (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Vaccines against Influenza WHO Position Paper–November 2012. Available online: https://www.who.int/wer/2012/wer8747.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2018–2019 Influenza Illnesses, Medical Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths Averted by Vaccination. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden-averted/2018-2019.htm (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Bergman, R. CDC: Fewer than half of Americans get flu vaccine. Nation Health 2017, 47, E45. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Flu Vaccination Coverage, United States, 2018–2019 Influenza Season. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1819estimates.htm#:~:text=Results,-Children%20(6%20months&text=Among%20children%206%20months%20through%2017%20years%2C%20the%20percentage%20receiving,(59.0%25%3B%20Figure%201) (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Increase the proportion of people who get the flu vaccine every year—IID-09, Healthy People 2030. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/vaccination/increase-proportion-people-who-get-flu-vaccine-every-year-iid-09 (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A Flu Disparities Among Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/highrisk/disparities-racial-ethnic-minority-groups.html (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Tse, S.C.; Wyatt, L.C.; Trinh-Shevrin, C.; Kwon, S.C. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccination Rates Among Older Adults in New York City and Los Angeles and Orange Counties. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2018, 15, E159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, P.J.; Rodriguez-Lainz, A.; O’Halloran, A.; Greby, S.; Williams, W.W. Adult vaccination disparities among foreign-born populations in the U.S., 2012. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 47, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, A.E.; Reither, E.N.; Hofmann, E.T.; Mamelund, S.E. The Influence of Hispanic Ethnicity and Nativity Status on 2009 H1N1 Pandemic Vaccination Uptake in the United States. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Fox, S.A.; Cantrell, C.H.; Stockdale, S.E.; Kagawa-Singer, M. Health disparities and prevention: Racial/ethnic barriers to flu vaccinations. J. Community Health 2007, 32, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). About the National Health Interview Survey. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Gowda, C.; Schaffer, S.E.; Dombkowski, K.J.; Dempsey, A.F. Understanding attitudes toward adolescent vaccination and the decision-making dynamic among adolescents, parents and providers. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Flu Vaccination Coverage, United States, 2016–2017 Influenza Season. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1617estimates.htm#:~:text=Among%20all%20people%20%E2%89%A56,55.4%25%20(Rhode%20Island) (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Pew Research Center. Income Inequality in the U.S. Is Rising Most Rapidly Among Asians. Available online: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/07/12/income-inequality-in-the-u-s-is-rising-most-rapidly-among-asians/ (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Pew Research Center. The Rise of Asian Americans. Available online: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2012/06/19/the-rise-of-asian-americans/ (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Engelman, M.; Ye, L.Z. The Immigrant Health Differential in the Context of Racial and Ethnic Disparities: The Case of Diabetes. Adv. Med. Sociol. 2019, 19, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N.K.; Sudharsanan, N.; Elo, I.T. Race/ethnicity and disability among older Americans. In Handbook of Minority Aging; Springer: New York, USA, 2013; pp. 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Chapter 1: Statistical Portrait of the U.S. Black Immigrant Population. Available online: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/04/09/chapter-1-statistical-portrait-of-the-u-s-black-immigrant-population/ (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Dubov, A.; Phung, C. Nudges or mandates? The ethics of mandatory flu vaccination. Vaccine 2015, 33, 2530–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coady, M.H.; Galea, S.; Blaney., S.; Ompad, D.C.; Sisco, S.; Vlahov, D. Project VIVA: A multilevel community-based intervention to increase influenza vaccination rates among hard-to-reach populations in New York City. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ompad, D.C.; Galea, S.; Vlahov, D. Distribution of influenza vaccine to high-risk groups. Epidemiol. Rev. 2006, 28, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Yoon, J. The use of an online forum for health information by married Korean women in the United States. Inf. Res. 2012, 17, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Park, M.S. Cancer information-seeking behaviors and information needs among Korean Americans in the online community. J. Community Health 2014, 39, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtright, C. Health information-seeking among Latino newcomers: An exploratory study. Inf. Res. 2005, 10, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, C.; Beck, A.F. Measuring Vaccine Hesitancy in a Minority Community. Clin. Pediatr. 2017, 56, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. Framework for Equitable Allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Interactive. Flu shots. Available online: https://www.medicareinteractive.org/get-answers/medicare-covered-services/preventive-services/flu-shots#:~:text=If%20you%20qualify%2C%20Original%20Medicare,(no%20deductible%20or%20coinsurance) (accessed on 18 October 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Who Needs a Flu Vaccine and When. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/vaccinations.htm#:~:text=Everyone%206%20months%20and%20older,of%20serious%20complications%20from%20influenza (accessed on 18 October 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Influenza Vaccination Information for Health Care Workers. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/healthcareworkers.htm#:~:text=CDC%2C%20the%20Advisory%20Committee%20on,get%20vaccinated%20annually%20against%20influenza (accessed on 18 October 2020).

- Blank, C.; Gemeinhart, N.; Dunagan, W.C.; Babcock, H.M. Mandatory employee vaccination as a strategy for early and comprehensive health care personnel immunization coverage: Experience from 10 influenza seasons. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2020, 48, 1133–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.J.; Hung, M.C.; O’Halloran, A.C.; Ding, H.; Srivastav, A.; Williams, W.W.; Singleton, J.A. Seasonal Influenza Vaccination Coverage Trends Among Adult Populations, U.S., 2010-2016. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, S.C.; Jamison, A. Will the public take a universal influenza vaccine?: The need for social and behavioral science research. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 1798–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Influenza update-390. Available online: https://www.who.int/influenza/surveillance_monitoring/updates/latest_update_GIP_surveillance/en/ (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Markides, K.S.; Rote, S. Immigrant Health Paradox. Emerg. Trends Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, T.G.; Hummer, R.A. Immigration and the health of U.S. black adults: Does country of origin matter? Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 1551–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bish, A.; Yardley, L.; Nicoll, A.; Michie, S. Factors associated with uptake of vaccination against pandemic influenza: A systematic review. Vaccine 2011, 29, 6472–6484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Health Coverage of Immigrants. Available online: https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/ (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Changes in Health Coverage by Race and Ethnicity since the ACA, 2010-2018. Available online: https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/changes-in-health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-since-the-aca-2010-2018/ (accessed on 13 October 2020).

| All (n = 25,045) | Did Not Receive Influenza Vaccine (n = 13,121) | Received Influenza Vaccine (n = 11,924) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.000 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 51.72 (18.33) | 46.87 (17.06) | 57.04 (18.20) | |

| 18–49 years | 11,355 (45.34) | 7348 (56.00) | 4007 (33.60) | |

| 50–64 years | 6477 (25.86) | 3468 (26.43) | 3009 (25.23) | |

| 65 years or older | 7213 (28.80) | 2305 (17.57) | 4908 (41.16) | |

| Sex | 0.000 | |||

| Male | 11,396 (45.50) | 6461 (49.24) | 4935 (41.39) | |

| Female | 13,649 (54.50) | 6660 (50.76) | 6989 (58.61) | |

| Marital status | 0.000 | |||

| Unmarried | 13,645 (54.60) | 7642 (58.40) | 6003 (50.42) | |

| Married | 11,346 (45.40) | 5444 (41.60) | 5902 (49.58) | |

| Nativity | 0.000 | |||

| US-born | 21,061 (84.25) | 10,819 (82.64) | 10,242 (86.03) | |

| Foreign-born | 3936 (15.75) | 2273 (16.36) | 1663 (13.97) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.000 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 17,129 (68.39) | 8460 (64.48) | 8669 (72.70) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2779 (11.10) | 1692 (12.90) | 1087 (9.12) | |

| Hispanic | 3136 (12.52) | 1922 (14.65) | 1214 (10.18) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1257 (5.02) | 628 (4.79) | 629 (5.28) | |

| Non-Hispanic others | 744 (2.97) | 419 (3.19) | 325 (2.73) | |

| Education | 0.000 | |||

| Below high school | 2268 (9.09) | 1271 (9.73) | 997 (8.39) | |

| High school graduate | 6579 (26.37) | 3730 (28.54) | 2849 (23.98) | |

| Some college | 7552 (30.27) | 4169 (31.90) | 3383 (28.47) | |

| College graduate | 5340 (21.40) | 2645 (20.24) | 2695 (22.68) | |

| Graduate education | 3212 (12.87) | 1254 (9.60) | 1958 (16.48) | |

| Employment status and work industry | 0.000 | |||

| Unemployed | 11,156 (44.56) | 4863 (37.40) | 6293 (53.04) | |

| Employed work industry | ||||

| Healthcare | 1766 (7.10) | 540 (4.15) | 1226 (10.33) | |

| Agriculture, mining | 248 (1.00) | 170 (1.31) | 78 (0.66) | |

| Construction | 897 (3.61) | 682 (5.25) | 215 (1.81) | |

| Utilities and manufacturing | 1419 (5.71) | 887 (6.82) | 532 (4.48) | |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 1638 (6.59) | 1117 (8.59) | 521 (4.39) | |

| Transportation and warehousing | 617 (2.48) | 440 (3.38) | 177 (1.49) | |

| Information | 272 (1.09) | 153 (1.18) | 119 (1.00) | |

| Finance and insurance | 705 (2.83) | 384 (2.95) | 320 (2.70) | |

| Real estate and rental leasing | 312 (1.25) | 214 (1.65) | 98 (0.83) | |

| Services | 5066 (20.37) | 3160 (24.31) | 1906 (16.07) | |

| Public administration and armed forces | 770 (3.10) | 391 (3.03) | 379 (3.19) | |

| Poverty level | 0.000 | |||

| At or above | 21,099 (88.22) | 10,867 (86.43) | 10,232 (90.21) | |

| Below | 2817 (11.78) | 1706 (13.57) | 1111 (9.79) | |

| Health insurance | 0.000 | |||

| Uninsured | 2278 (9.12) | 1893 (14.48) | 385 (3.23) | |

| Insured | 22,693 (90.88) | 11,176 (85.52) | 11,517 (96.77) | |

| Usual source of care | 0.000 | |||

| No | 3096 (12.36) | 2470 (18.83) | 626 (5.25) | |

| Yes | 21,945 (87.64) | 10,648 (81.17) | 11,297 (94.75) | |

| Self-reported health | 0.000 | |||

| Good/fair/poor | 10,491 (41.90) | 5148 (39.25) | 5343 (44.82) | |

| Excellent/very good | 14,546 (58.10) | 7967 (60.75) | 6579 (55.18) | |

| Years in the U.S. (among foreign-born) | 0.000 | |||

| 10 years or longer | 3218 (82.18) | 1795 (79.50) | 1423 (85.83) | |

| <10 years | 698 (17.82) | 463 (20.50) | 235 (14.17) |

| All | US-Born | Foreign-Born | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18–49 years (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 50–64 years | 1.436 (1.339–1.539 *** | 1.490 (1.381–1.608) *** | 1.173 (0.977–1.408) |

| 65 years or older | 3.058 (2.823–3.312) *** | 3.135 (2.873–3.419) *** | 2.539 (2.039–3.161) *** |

| Sex | |||

| Male (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Female | 1.125 (1.061–1.192) *** | 1.150 (1.079–1.225) *** | 1.016 (0.872–1.183) |

| Nativity | |||

| Foreign-born (ref) | 1.0 | - | - |

| U.S.-born | 1.195 (1.083–1.318) *** | - | - |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.685 (0.623–0.753) *** | 0.634 (0.573–0.701) *** | 1.316 (0.985–1.758) |

| Hispanic | 1.063 (0.959–1.178) | 0.978 (0.861–1.110) | 1.298 (1.057–1.594) * |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1.148 (0.991–1.331) | 1.346 (1.029–1.762) * | 1.427 (1.157–1.760) *** |

| Non-Hispanic others | 1.036 (0.876–1.224) | 1.044 (0.875–1.245) | 1.237 (0.703–2.176) |

| Marital status | |||

| Unmarried (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Married | 1.216 (1.147–1.289) *** | 1.211 (1.136–1.291) *** | 1.168 (1.006–1.355) * |

| Education | |||

| Below high school (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| High school graduate | 0.961 (0.858–1.077) | 0.999 (0.874–1.141) | 0.945 (0.752–1.187) |

| Some college | 1.025 (0.914–1.148) | 1.093 (0.958–1.248) | 0.851 (0.666–1.088) |

| College graduate | 1.394 (1.234–1.575) *** | 1.525 (1.323–1.757) *** | 1.032 (0.800–1.332) |

| Graduate education | 1.954 (1.709–2.234) *** | 2.139 (1.831–2.498) *** | 1.501 (1.131–1.991) ** |

| Employment status | |||

| Unemployed (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Employed work industry | |||

| Healthcare | 2.871 (2.537–3.250) *** | 2.818 (2.459–3.229) *** | 3.039 (2.235–4.132) *** |

| Agriculture, mining | 0.649 (0.484–0.869) ** | 0.589 (0.426–0.816) *** | 1.000 (0.508–1.966) |

| Construction | 0.498 (0.417–0.594) *** | 0.470 (0.387–0.570) *** | 0.611 (0.397–0.939) * |

| Utilities and manufacturing | 0.775 (0.682–0.881) *** | 0.787 (0.684–0.906) *** | 0.723 (0.529–0.988) * |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 0.626 (0.553–0.708) *** | 0.627 (0.549–0.717) *** | 0.600 (0.423–0.851) ** |

| Transportation and warehousing | 0.585 (0.481–0.710) *** | 0.543 (0.437–0.674) *** | 0.763 (0.487–1.196) |

| Information | 0.871 (0.672–1.128) | 0.927 (0.799–1.229) | 0.623 (0.315–1.232) |

| Finance and insurance | 0.885 (0.749–1.045) | 0.873 (0.729–1.047) | 0.930 (0.601–1.439) |

| Real estate and rental leasing | 0.474 (0.364–0.616) *** | 0.458 (0.343–0.612) *** | 0.600 (0.314–1.144) |

| Services | 0.705 (0.648–0.766) *** | 0.684 (0.624–0.750) *** | 0.769 (0.628–0.942) * |

| Public administration and armed forces | 1.002 (0.853–1.175) | 0.984 (0.830–1.166) | 1.115 (0.675–1.843) |

| Poverty level | |||

| At or above (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Below | 0.983 (0.894–1.082) | 0.960 (0.861–1.069) | 1.102 (0.895–1.356) |

| Health insurance | |||

| Uninsured (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Insured | 2.317 (2.041–2.629) *** | 2.682 (2.303–3.124) *** | 1.802 (1.416–2.293) *** |

| Usual source of care | |||

| No (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 2.342 (2.112–2.599) *** | 2.373 (2.112–2.666) *** | 2.367 (1.872–2.993) *** |

| Self-reported health | |||

| Good/fair/poor (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Excellent/very good | 0.865 (0.814–0.919) *** | 0.838 (0.785–0.895) *** | 0.988 (0.844–1.157) |

| Years in the U.S. (foreign-born only) | |||

| 10 years or longer | - | - | 1.0 |

| <10 years | - | - | 0.969 (0.789–1.190) |

| Cons | 0.100 (0.081–0.122) *** | 0.098 (0.079–0.121) *** | 0.124 (0.082–0.187) *** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1216 | 0.1263 | 0.1049 |

| N | 23,616 | 19.951 | 3,643 |

| NH White | NH Black | Hispanic | NH Asian | NH Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| 18–49 years (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 50–64 years | 1.437 (1.321–1.562) *** | 1.612 (1.301–1.998) *** | 1.306 (1.063–1.605) * | 1.352 (0.962–1.900) | 1.632 (1.082–2.460) * |

| 65 years or older | 3.076 (2.796–3.384) *** | 3.114 (2.439–3.976) *** | 2.728 (2.115–3.519) *** | 3.333 (2.267–4.900) *** | 2.505 (1.548–4.053) *** |

| Sex | |||||

| Male (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Female | 1.150 (1.072–1.233) *** | 0.928 (0.772–1.114) | 1.183 (0.994–1.409) | 1.130 (0.871–1.465) | 1.232 (0.872–1.741) |

| Nativity | |||||

| Foreign-born (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| U.S.-born | 1.619 (1.382–1.897) *** | 0.646 (0.493–0.847) ** | 1.063 (0.891–1.267) | 1.587 (1.147–2.195) ** | 1.307 (0.711–2.402) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Unmarried (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Married | 1.169 (1.091–1.253) *** | 1.246 (1.018–1.526) * | 1.150 (0.973–1.358) | 1.461 (1.104–1.933) ** | 1.639 (1.144–2.348) ** |

| Education | |||||

| Below high school (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| High school graduate | 1.079 (0.920–1.266) | 1.171 (0.875–1.566) | 0.871 (0.691–1.098) | 0.777 (0.421–1.433) | 0.485 (0.265–0.888) * |

| Some college | 1.215 (1.037–1.424) * | 1.224 (0.906–1.653) | 0.817 (0.638–1.045) | 0.623 (0.340–1.142) | 0.503 (0.277–0.913) * |

| College graduate | 1.668 (1.414–1.969) *** | 1.484 (1.041–2.116) * | 1.056 (0.787–1.419) | 0.880 (0.492–1.574) | 0.759 (0.378–1.525) |

| Graduate education | 2.367 (1.981–2.829) *** | 1.778 (1.191–2.653) ** | 1.699 (1.163–2.481) ** | 1.160 (0.632–2.129) | 1.262 (0.561–2.837) |

| Employment status | |||||

| Unemployed (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Employed work industry | |||||

| Healthcare | 2.926 (2.500–3.424) *** | 2.452 (1.761–3.414) *** | 2.522 (1.807–3.520) *** | 4.200 (2.400–7.350) *** | 3.445 (1.651–7.186) *** |

| Agriculture, mining | 0.615 (0.437–0.865) ** | 0.425 (0.085–2.103) | 0.997 (0.499–1.991) | 0.754 (0.124–4.562) | 0.543 (0.052–5.645) |

| Construction | 0.484 (0.394–0.594) *** | 0.169 (0.050–0.574) ** | 0.576 (0.366–0.904) * | 0.526 (0.183–1.151) | 0.994 (0.387–2.549) |

| Utilities and manufacturing | 0.748 (0.642–0.871) *** | 0.749 (0.475–1.179) | 0.856 (0.594–1.235) | 0.962 (0.656–1.636) | 1.036 (0.430–2.494) |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 0.604 (0.522–0.599) *** | 0.819 (0.532–1.257) | 0.802 (0.565–1.140) | 0.448 (0.251–0.799) ** | 0.439 (0.191–1.005) |

| Transportation and warehousing | 0.505 (0.394–0.646) *** | 0.480 (0.288–0.800) ** | 1.103 (0.634–1.918) | 1.047 (0.489–2.242) | 0.573 (0.194–1.692) |

| Information | 0.882 (0.655–1.189) | 0.929 (0.337–2.255) | 0.812 (0.291–2.267) | 0.756 (0.288–1.982) | 1.271 (0.284–5.673) |

| Finance and insurance | 0.894 (0.733–1.092) | 0.620 (0.348–1.103) | 1.019 (0.616–1.686) | 1.010 (0.539–1.921) | 1.484 (0.432–5.097) |

| Real estate and rental leasing | 0.484 (0.358–0.655) *** | 0.491 (0.189–1.277) | 0.526 (0.238–1.162) | 0.242 (0.049–1.182) | 0.340 (0.027–4.169) |

| Services | 0.693 (0.626–0.768) *** | 0.644 (0.495–0.836) *** | 0.814 (0.648–1.023) | 0.740 (0.516–1.062) | 0.608 (0.377–0.980) |

| Public administration and armed forces | 1.003 (0.827–1.218) | 0.850 (0.548–1.317) | 1.153 (0.684–1.946) | 1.251 (0.560–2.798) | 1.122 (0.474–2.653) |

| Poverty level | |||||

| At or above (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| below | 0.856 (0.750–0.977) * | 1.110 (0.886–1.389) | 1.136 (0.911–1.417) | 1.165 (0.749–1.813) | 1.059 (0.684–1.638) |

| Health insurance | |||||

| Uninsured (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Insured | 3.113 (2.583–3.750) *** | 1.976 (1.369–2.852) *** | 2.058 (1.601–2.645) *** | 1.328 (0.727–2.423) | 1.508 (0.922–2.466) |

| Usual source of care | |||||

| No (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 2.415 (2.119–2.752) *** | 2.648 (1.863–3.765) *** | 1.993 (1.553–2.557) *** | 2.608 (1.713–3.970) *** | 2.359 (1.328–4.190) ** |

| Self-reported health | |||||

| Good/fair/poor (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Excellent/very good | 0.838 (0.779–0.902) *** | 0.870 (0.722–1.049) | 0.887 (0.746–1.054) | 0.978 (0.733–1.305) | 0.890 (0.626–1.265) |

| Cons | 0.049 (0.036–0.066) *** | 0.119 (0.067–0.210) *** | 0.151 (0.104–0.219) *** | 0.193 (0.080–0.464) *** | 0.206 (0.071–0.591) ** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1242 | 0.1097 | 0.1049 | 0.1286 | 0.1238 |

| N | 16,257 | 2579 | 2909 | 1169 | 702 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jang, S.H.; Kang, J. Factors Associated with Influenza Vaccination Uptake among U.S. Adults: Focus on Nativity and Race/Ethnicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5349. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105349

Jang SH, Kang J. Factors Associated with Influenza Vaccination Uptake among U.S. Adults: Focus on Nativity and Race/Ethnicity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(10):5349. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105349

Chicago/Turabian StyleJang, Sou Hyun, and JaHyun Kang. 2021. "Factors Associated with Influenza Vaccination Uptake among U.S. Adults: Focus on Nativity and Race/Ethnicity" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 10: 5349. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105349

APA StyleJang, S. H., & Kang, J. (2021). Factors Associated with Influenza Vaccination Uptake among U.S. Adults: Focus on Nativity and Race/Ethnicity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5349. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105349