Strengthening Antenatal Care towards a Salutogenic Approach: A Meta-Ethnography

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Theoretical Perspective

2.2. The Review

2.2.1. The Aim

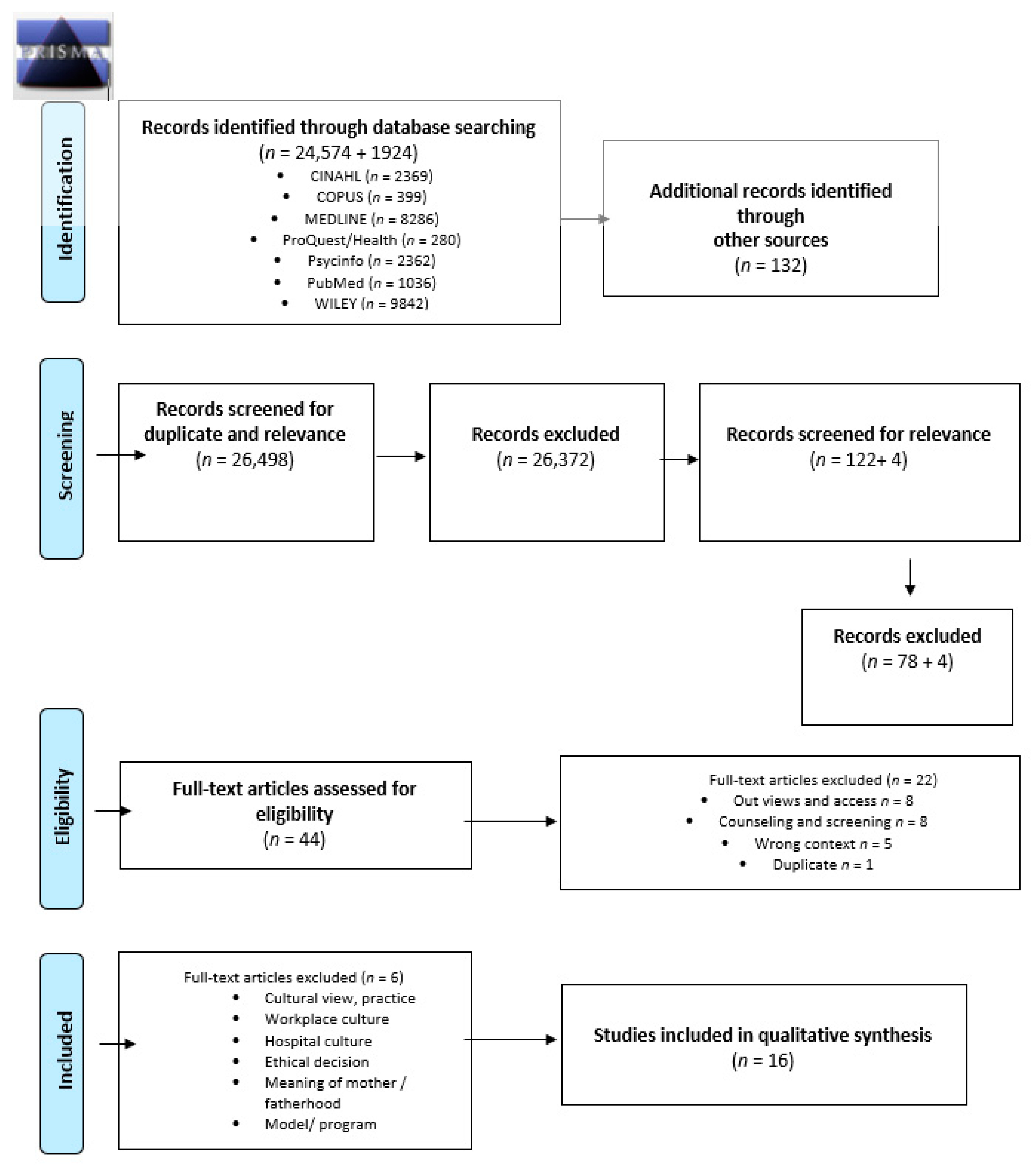

2.2.2. Design

2.2.3. Method

2.2.4. Quality Appraisal

2.2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Supporting the Parents to Awaken to Parenthood and Creating a Firm Foundation for Early Parenting and Their New Situation

3.1.1. Welcoming, Being Actively Present and Available

3.1.2. Connecting and Creating a Relationship with Both Parents

3.1.3. Building Continuity and Trust in the Relationship between Midwife and Women

3.1.4. Actively Getting to Know the Father/Partner to Encourage and Engage Them

3.1.5. Recognizing the Importance of Language in Providing Support and Dealing with Challenges

3.2. Guiding Parents on the Path to Parenthood and New Responsibility

3.2.1. Listening to Each Person to Encourage Participation

3.2.2. Supporting Women’s Self-Determination

3.2.3. Building and Supporting the Confidence of Fathers/Partners

3.3. Ensuring Normality and the Bond between Baby and Parents While Protecting Life

3.3.1. Taking Care through Measurements and Tests

3.3.2. Promoting the Bond with the Unborn Child by Offering Information and Guidance

3.3.3. Cultural Challenges and Preventing Possible Health Risks

3.4. Promoting the Health and Wellbeing of the Family Today and in the Future

3.4.1. Providing and Sharing Information and Support through Parenting Education

3.4.2. Seeing the Importance of Family Members and Networks and Accepting Them in Antenatal Care

3.4.3. Helping Parents Connect with Other People and Get Peer Support

3.4.4. A Metaphor

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meleis, A.I. Theoretical Nursing: Development End Progress, 3rd ed.; Lippincott: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- International Code of Ethics for Midwives. Strengthening Midwifery Globally. 2014. Available online: https://www.internationalmidwives.org/our-work/policy-and-practice/international-code-of-ethics-for-midwives.html (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- International Confederation of Midwives. 2021. Available online: https://www.internationalmidwives.org/ (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Wright, D.; Pincombe, J.; McKellar, L. Exploring routine hospital antenatal care consultations—An ethnographic study. Women Birth 2018, 31, e162–e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sword, W.; Heaman, M.I.; Brooks, S.; Tough, S.; Janssen, P.A.; Young, D.; Kingston, D.; Helewa, M.E.; Akhtar-Danesh, N.; Hutton, E. Women’s and care providers’ perspectives of quality prenatal care: A qualitative descriptive study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, A.M.; Ridgeway, J.L.; Stirn, S.L.; Morris, M.A.; Branda, M.E.; Inselman, J.W.; Finnie, D.M.; Baker, C.A. Increasing the Connectivity and Autonomy of RNs with Low-Risk Obstetric Patients Findings of a study exploring the use of a new prenatal study. Am. J. Nurs. 2018, 118, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, M.R.J.V.; Edge, D.; Smith, D.M. Pregnancy as an ideal time for intervention to address the complex needs of black and minority ethnic women: Views of British midwives. Midwifery 2015, 31, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Family Federation of Finland. Terveyden ja Hyvinvoinnin Laitos. 2021. Available online: https://thl.fi/fi/web/sukupuolten-tasa-arvo/tasa-arvon-tila/perheet-ja-vanhemmuus/perheiden-moninaisuus (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- WHO. Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. World Health Organization, 2016. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250796/9789241549912-eng.pdf;jsessionid=A91AFCD71A8DCF01C4DF0807552BC594?sequence=1 (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Draper, J. Men’s passage to fatherhood: An analysis of the contemporary relevance of transition theory. Nurs. Inq. 2003, 10, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, J. ‘It’s the first scientific evidence’: Men’s experience of pregnancy confirmation. J. Adv. Nurs. 2002, 39, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deave, T.; Johnson, D.; Ingram, J. Transition to parenthood: The needs of parents in pregnancy and early parenthood. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2008, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premberg, Å.; Hellström, A.-L.; Berg, M. Experiences of the first year as a father. Scand. Scaring Sci. 2008, 22, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, R.; Hall, P.; Daiches, A. Fathers’ experiences of their transition to fatherhood: A metasynthesis. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2011, 29, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, M.; Downe, S.; Bamford, N.; Edozien, L. Not patient and not-visitor: A meta-synthesis of fathers’ encounters with pregnancy, birth and maternity care. Midwifery 2012, 28, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, M.; Fenwick, R.M.; Premberg, R.N. A meta-synthesis of fathers’ experiences of their partner’s labour and the birth of their baby. Midwifery 2015, 31, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, J.; O’Brien, M.; Taylor, J.; Bowman, R.; Davis, D. ‘You’ve got it within you’: The political act of keeping a wellness focus in the antenatal time. Midwifery 2014, 30, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, J.; Lasenbatt, H.; Dunne, L. “Fear of childbirth» and ways of coping for pregnant women and their part-ners during the birthing process: A salutogenic analysis. Evid. Based Midwifery 2014, 12, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Quality Midwifery Care for Mothers and Newborns. World Health Organization, 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/quality-of-care/midwifery/en/ (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Ahldén, I.; Göransson, A.; Josefsson, A.; Alehagen, S. Parenthood education in Swedish antenatal care: Perceptions of midwives and obstetricians in charge. J. Périnat. Educ. 2008, 17, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, S.; Davis, D. ‘I’m having a baby not a labour’: Sense of coherence and women’s attitudes towards labour and birth. Midwifery 2019, 79, 102529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, S.; Browne, J.; Taylor, J.; Davis, D. Sense of coherence and women׳s birthing outcomes: A longitudinal survey. Midwifery 2016, 34, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, C.; Payne, D.; McAra-Couper, J. Midwives’ perspectives of maternal mental health assessment and screening for risk during pregnancy. N. Z. Coll. Midwives J. 2019, 55, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flink, M.S.; Urech, C.; Cavelti, M.; Alder, J. Relaxation during pregnancy: What are the benefits for mother, fetus and newborn? A systematic review of the literature. J. Perinat. Neonat. Nurs. 2012, 26, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollans, M.; Schmied, V.; Kemp, L.; Meade, T. ‘We just ask some questions…’ the process of antenatal psychosocial assessment by midwives. Midwifery 2013, 29, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikberg, A.; Eriksson, K.; Bondas, T. Intercultural caring from the perspectives of immigrant new mothers. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonat. Nurs. 2012, 41, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrne, M.; Schytt, E.; Andersson, E.; Small, R.; Adan, A.; Essén, B.; Byrskog, U. Antenatal care for Somali-born women in Sweden: Perspectives from mothers, fathers and midwives. Midwifery 2019, 74, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Jansson, L.; Norberg, A. Parenthood as talked about in Swedish ante- and postnatal midwifery con-sultations. A qualitative study of 58 video-recorded consultations. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 1998, 12, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Draper, J. ’It was a real good show’: The ultrasound scan, fathers and the power of visual knowledge. Sociol. Health Illn. 2002, 24, 771–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaila-Behm, A.; Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K. Ways of being a father: How first-time fathers and public health nurses perceive men as fathers. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2000, 37, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmore, M.; Rodger, D.; Humphreys, S.; Clifton, V.; Dalton, J.; Flabouris, M.; Skuse, A. How midwives tailor health information used in antenatal care. Midwifery 2015, 31, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noblit, G.W.; Hare, R.H. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M.; Barroso, J. Handbook for Synthesizing Qualitative Research; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Antonowsky, A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 1996, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, C.; Bull, T.; Mittelmark, M.; Vaandrager, L. Culture in salutogenesis: The scholarship of Aaron Antonovsky. Glob. Health Promot. 2014, 21, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, M.; Stockdale, J. Achieving optimal birth using salutogenesis in routine antenatal education. Evid. Based Midwifery 2011, 9, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey, S.; Ng, E.D. Application of the salutogenic theory in the perinatal period: A systematic mixed studies review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 101, 103398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinje, H.F.; Ausland, L.H.; Lamgeland, E. The application of salutogenesis in the training of health professionals. In Handbook of Salutogenesis; Mittelmark, M.B., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Bauer, G.F., Pelikan, J.M., Lindström, B., Espnes, G.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 307–318. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, S.; Glenton, C.; Munthe-Kaas, H.; Carlsen, B.; Colvin, C.J.; Gülmezoglu, M.; Noyes, J.; Booth, A.; Garside, R.; Rashidian, A. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: An approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, E.F.; Ring, N.; Noyes, J.; Maxwell, M.; Jepson, R.; Duncan, E.; Turley, R.L.; Jones, D.A.; Uny, I. Protocol-developing meta-ethnography reporting guidelines (eMERGe). BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2015, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, E.F.; Uny, I.; Ring, N.; Turley, R.L.; Maxwell, M.; Duncan, E.A.S.; Jepson, R.G.; Roberts, R.J.; Noyes, J. A methodological systematic review of meta-ethnography conduct to articulate the complex analytical phases. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.; Christensson, K.; Hildingsson, I. Swedish midwives’ perspectives of antenatal care focusing on group-based antenatal care. Int. J. Childbirth 2014, 4, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, J.A.; Rodger, D.L.; Wilmore, M.; Skuse, A.J.; Humphreys, S.; Flabouris, M.; Clifton, V.L. “Who’s afraid?”: Attitudes of midwives to the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) for delivery of pregnancy-related health information. Women Birth 2014, 27, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, S.; Muir-Cocrane, E. Being safe practitioners and safe mothers: A critical ethnography of continuity of care midwifery in Australia. Midwifery 2014, 30, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, L.; Hunter, B.; Jones, A. The midwife-woman relationship in a South Wales community: Experiences of midwives and migrant Pakistani women in early pregnancy. Health Expect. 2017, 21, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCourt, C. Supporting choice and control? Communication and interaction between midwives and women at the antenatal booking visit. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Sandman, P.-O.; Jansson, J. Antenatal “booking” interviews at midwifery clinics in Sweden: A qualita-tive analysis of five video-recorded interviews. Midwifery 1996, 12, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, S. What determines quality in maternity care? Comparing the perceptions of childbearing women and midwives. Birth 1998, 25, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rominov, H.; Giallo, R.; Pilkington, P.D.; Whelan, T.A. Midwives’ perceptions and experiences of engaging fathers in perinatal services. Women Birth 2017, 30, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saftner, M.A.; Neerland, C.; Avery, M.D. Enhancing women’s confidence for physiologic birth: Maternity care providers’ perspectives. Midwifery 2017, 53, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitford, H.M.; Entwistle, V.A.; Van Teijlingen, E.; Aitchison, P.E.; Davidson, T.; Humphrey, T.; Tucker, J.S. Use of a birth plan within woman-held maternity records: A qualitative study with women and staff in northeast Scotland. Birth 2014, 41, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; the PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and MetaAnalyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. Available online: www.prisma-statement.org (accessed on 10 May 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Grade Cerqual 2021. Grade-Cerqual Publications. Available online: https://www.cerqual.org/publications/ (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Dahl, B.; Heinonen, K.; Bondas, T.E. From midwife-dominated to midwifery-led antenatal care: A meta-ethnography. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist. 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2021).

| Criteria Headings | Reporting Criteria | Pages |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 Selecting meta-ethnography and getting started Introduction 1. Rationale and context for the meta-ethnography 2. Aim(s) of the meta-ethnography 3. Focus of the meta-ethnography 4. Rationale for using meta-ethnography | Describe the gap in research or knowledge to be filled by the meta-ethnography and the wider context of the meta-ethnography Describe the meta-ethnography aim(s) Describe the meta-ethnography review question(s) (or objectives) Explain why meta-ethnography was considered the most appropriate qualitative synthesis methodology | 1–3 |

| Phase 2 Deciding what is relevant Methods 5. Search strategy 6. Search processes 7. Selecting primary studies 8. Outcome of study selection | Describe the rationale for the literature search strategy Describe how the literature searching was carried out and by whom Describe the process of study screening and selection, and who was involved Describe the results of study searches and screening | 5–7, 9–14 |

| Phase 3 Reading included studies Methods 9. Reading and data-extraction approach Findings 10. Presenting characteristics of included studies | Describe the reading and data-extraction method and processes Describe characteristics of the included studies | 5–8, 9–14 |

| Phase 4 Determining how studies are related Methods 11. Process for determining how studies are related Findings 12. Outcome of relating studies | Describe the methods and processes for determining how the included studies are related: -Which aspects of studies were compared -How the studies were compared Describe how studies relate to each other | 8 |

| Phase 5 Translating studies into one another Methods 13. Process of translating studies Findings 14. Outcome of translation | Describe the methods of translation: -Describe steps taken to preserve the context and meaning of the relationships between concepts within and across studies -Describe how the reciprocal and refutational translations were conducted -Describe how potential alternative interpretations or explanations were considered in the translations -Describe the interpretive findings of the translation | 8, 15–23 |

| Phase 6 Synthesizing translations Methods 15. Synthesis process Findings 16. Outcome of synthesis process | Describe the methods used to develop overarching concepts (‘synthesized translations’), and describe how potential alternative interpretations or explanations were considered in the synthesis Describe the new theory, conceptual framework, model, configuration, or interpretation of data developed from the synthesis | 7–8, 15, 23 |

| Phase 7 Expressing the synthesis Discussion 17. Summary of findings 18. Strengths, limitations and reflexivity 19. Recommendations and conclusions | Summarize the main interpretive findings of the translation and synthesis, and compare them to existing literature Reflect on and describe the strengths and limitations of the synthesis: Methodological aspects: for example, describe how the synthesis findings were influenced by the nature of the included studies and how the meta-ethnography was conducted Reflexivity—for example, the impact of the research team on the synthesis findings Describe the implications of the synthesis | 15–23, 15, 26, 28 |

| The First | The Second | The Third |

|---|---|---|

| (Prenatal care and Visit*) or (antenatal care and visit*) and Midwi* | (Prenatal care and Visit*) or (antenatal care and visit*) and Public Health Nurs* | Prenatal care and Visit* or visit and Midwiv* or Public Health Nurs*and qualitative |

| Authors | Clear Aims | Appropriate Methodology | Appropriate Design | Appropriate Recruitment Strategy | Appropriate Data Collection | Adequate Consideration on Relationship between Researcher and Participants | Ethical Considerations | Rigorous Data Analysis | Clear Statement of Findings | The Value of the Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alden et al. (2008) [20] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | Y- | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Andersson et al. (2014) [42] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | Y- | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Aquino et al. (2015) [7] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | Y- | YY | Y- | YY | YY |

| Baron et al. (2018) [6] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -- | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Browne et al. (2014) [17] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -- | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Dalton et al. (2014) [43] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -- | Y- | Y- | YY | YY |

| Dove et al. (2014) [44] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | Y- | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Goodwin et al. (2018) [46] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -- | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| McCourt (2006) [46] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -- | -- | YY | YY | YY |

| Olsson et al. (1996) [47] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | Y- | Y- | YY | YY | YY |

| Proctor (1998) [48] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -- | -Y | yy | yy | YY |

| Rominov et al. (2017) [49] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Saftner et al. (2017) [50] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -- | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Sword et al. (2012) [5] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Withford et al. (2014) [53] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -- | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Wright et al. (2018) [4] | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -Y | YY | -Y | YY | YY |

| Author(s), Year, Country | Study Design and Aim(s) of Study | Sample of Participants | Context | Method of Data Collection and Analyses | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahlden et al. (2008) [20] Sweden | Phenomenograpy To describe perceptions of parenthood education (PEC) among midwives and obstetricians in charge of antenatal care in Sweden. | n = 25 Midwives (n = 13) and obstetricians (n = 12) | Swedish antenatal care | Focus group interviews Thematic analysis | There is a strong belief in PEC and the overall aim was considered to be support in the transition to parenthood. A good transition is influenced by several factors such as expectations, levels of knowledge, and the parents’ environment. Father-to-be sessions with male leaders is very important. |

| Andersson et al. (2014) [21] Sweden | An interview study To investigate and describe antenatal midwives’ perceptions and experiences of their current work, with a special focus on their opinions about GBAC (group-based antenatal care). | Midwives (n = 56) | 52 antenatal clinics. | Triangulation Descriptive statistics Content analysis | The midwives were satisfied with their work in antenatal care but have reservations concerning lack of time and content, individual care and quality of parental classes. They had strong opinions about women’s suitability for the model. GBAC can be more discussion-based and adapted to modern parents. |

| Aquino et al. (2015) [7] UK | Qualitative research To explore a cohort of midwives’ experience of providing care for BME (Black and minority) women, focusing on their views on the relationship between maternal health inequalities and service delivery. | Midwives (n = 20) | Hospital | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis | Many minority women’s complex care needs were identified during pregnancy by midwives. Whilst midwives strove to provide high-quality, individualized care for all women by being sensitive and responsive to women’s individual needs, many barriers were present such as organizational, language and cultural differences. |

| Baron et al. (2018) [6] USA | Qualitative evaluation To explore the perspectives of patients, RNs (Registered Nurse), and other providers regarding a new prenatal connected care model for low-risk patients aimed at reducing in-office visits and creating virtual patient-RN connectors. | Patients (n = 41) Other providers (n = 17), (physicians n = 8 and certified nurse midwives (CNMs) n = 9) | 10 units/hospital | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis | By reducing the number of scheduled in-office visits and increasing the RN’s role in patient management and education, the new parental care model sought to make more efficient use of the health care team. It also provides patients with greater flexibility and control of their care. The new model valued connectedness and the relationship with the connected care RNs. The connected care RNs appreciated being able to work to a fuller scope of practice. |

| Browne et al. (2014) [17] Australia | Qualitative To explore midwives’ communication techniques intended to promote a wellness focus in the antenatal period, this study identifies strategies midwives use to amplify women’s own resources and capacity, with the aim of reducing antenatal anxiety. | Midwives (n = 14) | Multiple hospitals and community settings | Focus group interviews Means of generating data | The midwives want to make the system of ANC (antenatal care) work for women. Wellness-focused care is both a responsibility and a right. The midwives used individually a variety of strategies in ANC specifically intended to facilitate women’s capabilities, to employ worry usefully and to reduce anxiety. |

| Dalton et al. (2014) [43] Australia | Triangulation To investigate midwives’ attitude and experiences of ICT (information and communication technologies) use to identify potential causal factors that limit usage. | Midwives (n = 40) | Single hospital | Focus group interviews. Thematic and statistical analyses. | The midwives recognize both potential benefits and possible risks in the use of ICT. The problems were lack of training, the perceived legal risks associated with social media, potential violations of patients’ privacy, misdiagnosis and misunderstanding between midwife and client. |

| Dove and Muir-Cocrane (2014) [44] Australia | Ethnography To examine how midwives and women within a continuity of care midwifery program in Australia conceptualized childbirth risk and the influences of these conceptualizations on women’s choices and midwives’ practice. | Midwives (n = 8), an obstetrician (n = 1) and women (n = 17) | Antenatal appointments | Semi-structured interviews, observation. | The relationship between the midwives and the women for the success of the continuity of care is important. Identities as safe mothers and practitioners developed out of intersubjective processes within their relationship. |

| Goodwin et al. (2018) [45] UK | Ethnography To address the paucity of literature examining the midwife-woman relationship for migrant women by exploring the relationship between first-generation migrant women and midwives focusing on identifying the factors contributing to these relationships, and the ways in which these relationships might affect women’s experiences of care. | Midwives (n = 11) and Pakistani migrant women (n = 9) in early pregnancy. | Community-based antenatal clinics | Interviews, Observation Thematic analysis | The midwife-woman relationship was important for maternity care, pregnancy outcomes and staff satisfaction. The midwives allowed the partner to be present, but some women seem to be unaware of their partner’s involvement. Numerous social and ecological factors influenced this relationship, including the family relationship, culture and religion, differing health-care systems, authoritative knowledge and communication of information. |

| McCourt (2006) [46] UK | An observational approach To explore whether, or how, the recent reforms to promote more women-centered care would have a positive impact on interaction between midwives and their clients, particularly regarding the areas of information and choice which have been so extensively critiqued. | Booking visits with pregnant women (n = 40) and midwives (n = 40) | Hospital clinic, GP clinic and women’s homes. | Observations Structured and qualitative analysis | The interactional patterns differed according to the model of care, i.e., conventional or caseload, and setting of care. A continuum of styles of communication was identified, with the prevalent styles also differing according to location and organization of care. The caseload visits showed less hierarchical and more conversational form and supported women’s reports and gave them greater information, choice and control. |

| Olsson et al. (1996) [47] Sweden | Qualitative To describe antenatal “booking” interviews as regards and illuminating the meaning of the ways midwives and expectant parents relate to each other. | Midwives (n = 5) Women (n = 5) Fathers (n = 2) | Midwifery clinics at five health centers in Sweden. | Video-recorded antenatal booking interviews. Content analysis Phenomenological hermeneutic analysis | There are two views on providing ANC. The former focused on the physical process of pregnancy and birth; the latter on the process of becoming parents including the psychological and social circumstances in addition to the physical. The ways midwives related were considering and disregarding the uniqueness of the expectant parents. The expectant fathers seemed like strange visitors in the women’s world. |

| Proctor (1998) [48] UK | Qualitative To identify and compare the perceptions of women and midwives concerning women’s beliefs about what constitutes quality in maternity services. | Midwives (n = 47) Women (n = 33) | Maternity clinics Hospital and community based | Focus group interviews Thematic analysis | The ANC was characterized primarily by a need for information, understanding and reassurance. Understanding and respect between women and midwives are important aspects of maternity care. It is important to know midwife before labor. The midwives overestimated the importance women attached to discussing information leaflets during pregnancy. |

| Rominov et al. (2017) [49] Australia | Multi-method approach To describe midwives’ perceptions and experiences of engaging fathers in perinatal services. | Midwives (n = 106) | Perinatal services and fathers | Semi-structured telephone interviews Descriptive analyses | Engaging fathers is part of the midwives’ role and they acknowledged the importance of receiving education to develop knowledge and skills regarding fathers. Being father-inclusive should be given more emphasis by midwives. The midwife-led continuity of care as a model could be of benefit to fathers. |

| Saftner et al. (2017) [50] USA | Qualitative descriptive study Grounded theory To explore MCPs’ (Maternity Care Providers) beliefs and attitudes about physiologic birth and to identify components of antenatal care that providers believe may impact on a woman’s confidence in physiological labor and birth. | Maternity care providers (n = 31) Certified Nurse-Midwife (CNM) n = 14 Family medicine doctors n = 8 Obstetrician- Gynecologist n = 9 | Maternity care | Semi-structured interviews Inductive coding | Maternity care providers support a physiological approach to labor and birth and wish to enhance outcomes for mothers and babies. They would like to provide more information to women about the care during birth and support for women’s choices. |

| Sword et al. (2012) [5] Canada | Qualitative descriptive approach To explore women’s and care providers’ perspectives of quality prenatal care to inform the development of items for a new instrument, the Quality of Prenatal Care Questionnaire. | Prenatal care providers (n = 40), including obstetricians, family physicians, midwives and nurses (practiced in obstetrics/maternity care minimum 2 years). Pregnant women (n = 40). | Five urban centers across Canada | Semi-structured interviews Inductive approach | Interpersonalized care is an approachable interaction style that involves taking time. Having a meaningful relationship with prenatal care may be fundamental to the quality of care and involves trust. The appointment flexibility and clinical knowledge of professional belongs in the provision of quality care. |

| Withford et al. (2014) [51] UK | Exploratory qualitative and longitudinal study To consider use of a standard birth plan section within a national, woman-held maternity record. | Women (n = 42) Maternity service staff (n = 24) Midwives n = 15 (hospital n = 6) and community and/or midwife-led unit n = 9) Obstetricans n = 6 Grade n = 4 (Consultant n = 4, specialist trainee obstetrician or below n = 2) General practitioner n = 3 | Antenatal clinics | Interviews Thematic analysis | The staff and women were generally positive about the provision of the birth plan with the record. The birth plan could stimulate discussion about labor and birth options, and support communication about women’s preferences and concerns. It could also serve to facilitate and enhance women’s awareness of staff responsiveness to women during pregnancy and labor. |

| Wright et al. (2018) [4] Australia | Contemporary focused ethnography To address the question: “How are the principles of woman-centered care applied in the hospital antenatal care setting?” | Midwives (n = 16) | Six different public antenatal clinics and antenatal consultations. | Interviews Observation Thematic analysis | Behaviors that promote time for women to express their feelings and needs, particularly during ANC, are important and are key to supporting the woman’s self-determination. To assist midwives in providing woman-centered conversations and care, managerial support may also be required with realistic timeframes and expectations. |

| The Overarching Theme: Helping the Woman and Her Partner Prepare for Their New Life with the Child by Providing Individualized, Shared Care, Firmly Grounded and with a View of the Future | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Themes | Supporting the Parents to Awaken to Parenthood and Creating a Firm Foundation for Early Parenting and Their New Life Situation | Guiding Parents on the Path to Parenthood and New Responsibility | Ensuring Normality and the Bond between Baby and Parents While Protecting Life | Promoting the Health and Wellbeing of the Family Today and in the Future |

| Themes | Welcoming, being actively present and available Connecting and creating a relationship with both parents Building continuity and trust in the relationship between midwife and women Actively getting to know the father/partner to encourage and engage them Recognizing the importance of language in providing support and dealing with challenges | Listening to each person to encourage participation Supporting women’s self-determination Building and supporting the confidence of fathers/partners | Taking care through measurements and tests Promoting the bond with the unborn child by offering information and guidance Cultural challenges and preventing possible health risks | Providing and sharing information and support through parenting education Seeing the importance of family members and networks and accepting them in antenatal care Helping parents connect with other people and get peer support |

| Authors | Olsson et al. [34] Ahlden et al. [20] Sword et al. [5] Andersson et al. [42] Dove et al. [44] Browne et al. [17] Rominov [49] Saftner et al. [50] Goodwin et al. [45] Wright et al. [4] | Olsson et al. [47] Proctor [48] McCourt [46] Sword et al. [5] Rominov et al. [49] Saftner et al. [50] Andersson et al. [42] Browne et al. [17] Dove et al. [44] Withford et al. [51] Aquino et al. [7] Saftner et al. [50] Goodwin et al. [45] Wright et al. [4] | Proctor [48] McCourt [46] Sword et al. [5] Andersson et al. [42] Aquino et al. [7] Saftner et al. [50] Goodwin et al. [45] Wright et al. [4] | Ahlden et al. [20] Sword et al. [5] Dalton et al. [43] Andersson et al. [42] Rominow et al. [49] Saftner et al. [50] Baron et al. [6] Goodwin et al. [45] Wright et al. [4] |

| The Finding of the Review | Studies Contributing to the Review Finding | Assessment of Methodological Limitations | Assessment of Relevance | Assessment of Coherence | Assessment of Adequacy | Overall CERQual Assessment of Confidence and Summary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supporting the parents to awaken to parenthood and creating a firm foundation for early parenting and the new life situation | Welcoming, being actively present and available Connecting and creating a relationship with both parents Building continuity and trust in the relationship between midwife and women Actively getting to know the father/partner to encourage and engage them Recognizing the importance of language in providing support and dealing with challenges | Olsson et al. [34] Ahlden et al. [20] Sword et al. [5] Andersson et al. [42] Dove et al. [44] Browne et al. [17] Rominov [49] Saftner et al. [50] Goodwin et al. [45] Wright et al. [4] | Minor methodological limitations. Minor concerns on relationship between researcher and participants, minor concerns about analysis and ethical considerations and clarity about reflexivity. | Minor concerns about relevance. The primary studies support a review finding is applicable to the context. The ANC by midwives/nurses in different places/context and different countries. | Minor concerns regarding coherence. Data reasonably consistent within and across studies. The data from the primary studies (carefully chosen) and a review finding synthesises the data good. | Minor concerns about adequacy of data. The participant and the data are presented. The whole data is rich with 16 studies and it described though some quotations. | Moderate confidence. The review finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest. The minor methodological considerations, minor concerns about relevance, coherence and adequacy of data. |

| Guiding parents on the path to parenthood and new responsibility | Listening to each person to encourage participation Supporting women’s self-determination Building and supporting the confidence of fathers/partners | Olsson et al. [47] Proctor [48] McCourt [46] Sword et al. [5] Rominov et al. [49] Saftner et al. [50] Andersson et al. [42] Browne et al. [17] Dove et al. [44] Withford et al. [51] Aquino et al. [7] Saftner et al. [50] Goodwin et al. [45] Wright et al. [4] | Minor methodological limitations. Minor concerns about data analysis, clarity about reflexive, a few ethical clarities and relationship between researcher and participants. | Minor concerns about relevance. The primary studies support a review finding is applicable to the context. The ANC by midwives/nurses in different places/context and different countries. | Minor concerns regarding coherence. Data reasonably consistent within and across studies. The data from the primary studies (carefully chosen) and a review finding synthesises the data good. | Moderate concerns about adequacy of data. The participant and the data are presented. The whole data is rich with 16 studies and it described though some quotations. | Moderate confidence. The review finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest. The minor methodological considerations, minor concerns about relevance, coherence and adequacy of data. |

| Ensuring normality and the bond between baby and parents while protecting life | Taking care through measurements and tests Promoting the bond with the unborn child by offering information and guidance Cultural challenges and preventing possible health risks | Proctor [48] McCourt [46] Sword et al. [5] Andersson et al. [42] Aquino et al. [7] Saftner et al. [50] Goodwin et al. [45] Wright et al. [4] | Minor methodological limitations. Minor concerns about data analysis, clarity about reflexivity and clarity about ethical considerations. | Minor concerns about relevance. The primary studies support a review finding is applicable to the context. The primary studies support a review finding is applicable to the context. The ANC by midwives/nurses in different places/context and different countries. | Minor concerns regarding coherence. studies. Data reasonably consistent within and across studies.The data from the primary studies (carefully chosen) and a review finding synthesises the data good. | Minor concerns about adequacy of data. The participant and the data are presented. The whole data is rich with 16 studies and it described though some quotations. | Moderate confidence. The review finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest. The minor methodological considerations, minor concerns about relevance, coherence and adequacy of data. |

| Promoting the wellbeing and health of the family today and in the future | Providing and sharing information and support through parenting education Seeing the importance of family members and networks and accepting them in antenatal care Helping parents connect with other people and get peer support | Ahlden et al. [20] Sword et al. [5] Dalton et al. [43] Andersson et al. [42] Rominow et al. [49] Saftner et al. [50] Baron et al. [6] Goodwin et al. [45] Wright et al. [4] | Minor methodological limitations. Minor concerns about rigours of the data analysis, clarity about ethical considerations and relationship between researcher and participants. | Minor concerns about relevance. The primary studies support a review finding is applicable to the context. The ANC by midwives/nurses in different places/context and different countries. | Minor concerns regarding coherence. Data reasonably consistent within and across studies. The data from the primary studies (carefully chosen) and a review finding synthesises the data good. | Minor concerns about adequacy of data. The participant and the data are presented. The whole data is rich with 16 studies and it described though some quotations. | Moderate confidence. The review finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest. The minor methodological considerations, minor concerns about relevance, coherence and adequacy of data. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heinonen, K. Strengthening Antenatal Care towards a Salutogenic Approach: A Meta-Ethnography. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105168

Heinonen K. Strengthening Antenatal Care towards a Salutogenic Approach: A Meta-Ethnography. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(10):5168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105168

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeinonen, Kristiina. 2021. "Strengthening Antenatal Care towards a Salutogenic Approach: A Meta-Ethnography" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 10: 5168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105168

APA StyleHeinonen, K. (2021). Strengthening Antenatal Care towards a Salutogenic Approach: A Meta-Ethnography. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105168