Upgrading Nursing Students’ Foreign Language and Communication Skills: A Qualitative Inquiry of the Afterschool Enhancement Programmes

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose of the Study

- Why would nursing students decide to take Mandarin Chinese (i.e., rather than other foreign languages) as the tool for foreign language and culture development?

- 1.1

- What are the reasons and motivations for nursing students to take Mandarin Chinese courses and training beyond their curriculum and plans, and why?

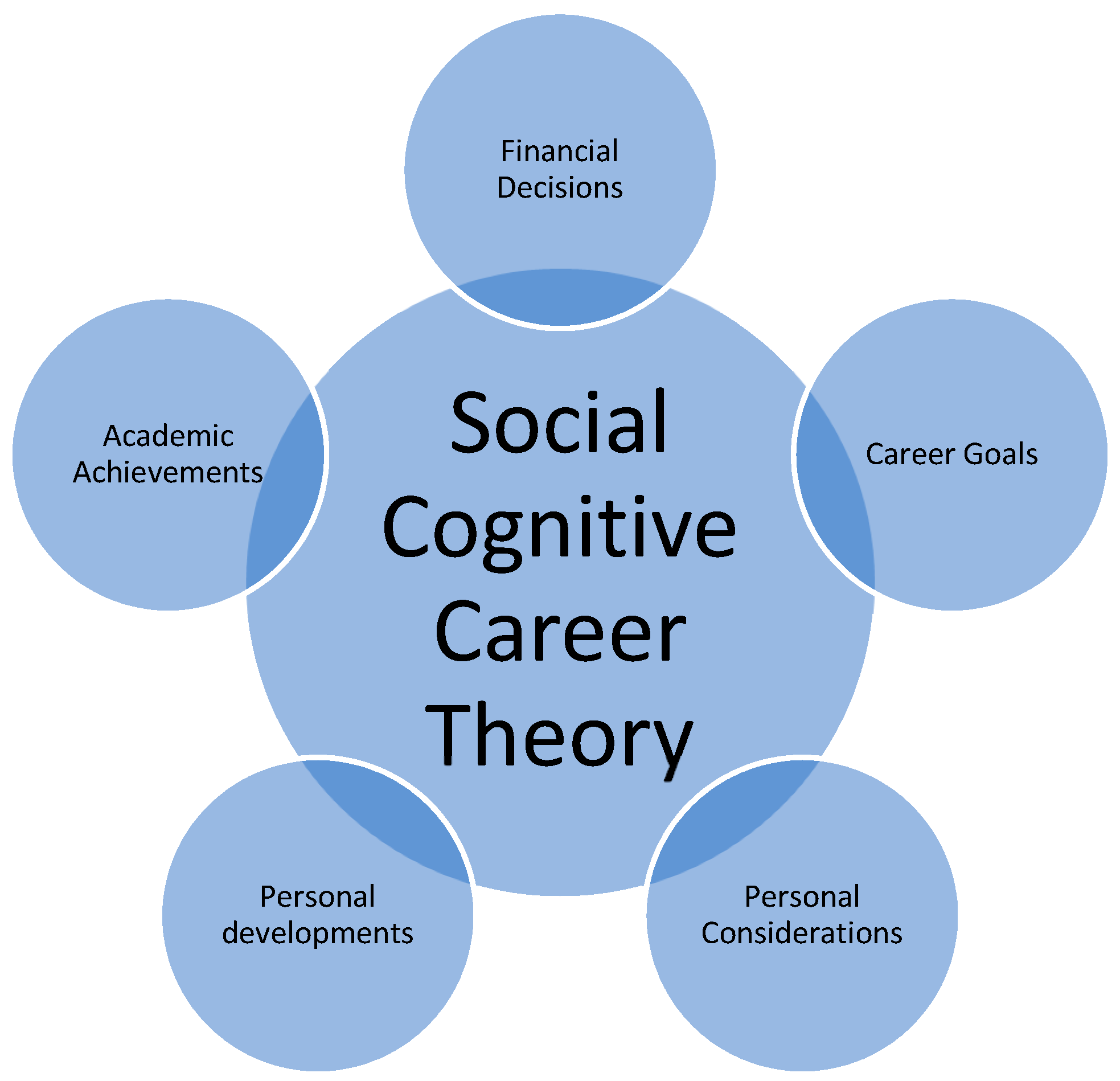

1.2. Theoretical Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study

2.2. The Afterschool Foreign Langauge Programme

2.3. Participants and Recruitments

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Human Subject Protection

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Mandarin Chinese as One of the Strongest Languages for Global Development

… there are many Chinese organisations and investments in Europe … it is a global trend to understand Chinese language and the related cultural behaviours … I would like to learn Chinese because I may enter the global business development in the future …(Participant #5, individual interview)

… there are many Chinese investments in the United Kingdom and Europe … if I can speak Chinese, I may join the developing workforce in the East Asian region … the economy in the United Kingdom is very negative … if I can speak Chinese, I may have better opportunities …(Participant #28, focus group)

3.1.1. Personal Development and Potential International Promotion

… there are too many people who can speak Spanish and French on the street … but there are many Chinese and East Asian patients who beg for help in Mandarin Chinese … I think if I can speak the language … it may be a great opportunity for personal development …(Participant #11, individual interview)

… I want to learn Chinese because I want to have a unique development … We have a lot of Chinese friends and residents in the United Kingdom … but most of the Mandarin Chinese speakers are Chinese or East Asian residents … I want to speak the Mandarin Chinese language as a non-East Asian … this experience is unique and will be beneficial to my personal enhancement …(Participant #13, individual interview)

… Chinese culture is not only fun … but also meaningful and excited … each Chinese character represents a historical story … unlike the current English words and sentences … Chinese is unique … I want to learn and enjoy this history in the Asian region …(Participant #16, individual interview)

Some alternative and oriental treatments are very useful for pain management … as I would like to learn more ideas from these alternative treatments, I learn to learn the roots of these … as many of the treatments are from the traditional Chinese medicine … I want to gain the language and cultural proficiency …(Participant #36, focus group)

There are many scholarships, and international development programmes are hosted by the Chinese agencies … I want to gain the scholarships and work in China for international development … so I want to learn Chinese … to prepare myself …(Participant #8, focus group)

In the future, I want to do some international charity works … there are many opportunities in the Chinese speaking regions, such as mainland China or some rural communities in Malaysia … they want to have some Chinese speaking volunteers … I want to be prepared for this international opportunities …(Participant #19, focus group)

3.2. The Multitude of Mandarin Chinese-Speaking Patients

Besides vocational and medical skill training, I think the medical staff in the United Kingdom should be trained as bilingual and bicultural professionals in order to meet the needs of our patients …(Participant #3, individual interview)

… If I can speak Chinese … I can serve not only Chinese patients but also many patients from the East Asian region as many speak Chinese … I can help a greater number of people …(Participant #31, focus group)

… Chinese residents are one of the important groups of people in our community … if I can speak the language, I can provide additional help and care to more people …(Participant #23, individual interview)

3.2.1. Cultural Awareness of the Mandarin Chinese Language: Cultural Understanding and Practices beyond Chinese People

… just the word painful … there are several different levels and explanation … before I joined the nursing school, I could not explain the level in detail … so the Chinese patients … I can serve as the tool to interpret the symptoms of my patients …(Participant #34, focus group)

… cultural exchanging and interaction are important in patient communication … many hospitals need to hire interpreters … but if we can speak the language, the overall process and duration will be reduced …(Participant #22, individual interview)

4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kennedy, K. Spanish Tops Languages to Learn in 2018, Says British Council. Available online: https://thepienews.com/news/learning-new-language-popular-resolution-2018-says-british-council-survey (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Mantle, R. Higher Education Student Statistics: UK, 2018/19; Higher Education Statistics Agency: Cheltenham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Duffin, E. The Most Spoken Languages Worldwide in 2019; Statista: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Evaluation checklist for English language teaching and learning for health science professionals. World Trans. Eng. Technol. Educ. 2019, 17, 431–436. [Google Scholar]

- Salamonson, Y.; Everett, B.; Koch, J.; Andrew, S.; Davidson, P. English-language acculturation predicts academic performance in nursing students who speak English as a Second Language. Res. Nurs. Health 2008, 31, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, B.C.; Meeuwesen, L. Cultural differences in medical communication: A review of the literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 2006, 64, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewett, D.G.; Watson, B.M.; Gallois, C.; Ward, M.; Leggett, B.A. Communication in medical records: Intergroup language and patient care. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 28, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuter, R.F.I.; Gallois, C.; Segalowitz, N.S.; Ryder, A.G.; Hocking, J. Overcoming language barriers in healthcare: A protocol for investigating safe and effective communication when patients or clinicians use a second language. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardet, A.; Green, A.R.; Paroz, S.; Singy, P.; Vaucher, P.; Bodenmann, P. Medical residents’ feedback on needs and acquired skills following a short course on cross-cultural competence. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2012, 3, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chae, D.; Park, Y.; Kang, K.; Kim, J. A multilevel investigation of cultural competence among South Korean clinical nurses. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2020, 34, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisol Moya, E.; Caurcel Cara, M.J. Percepciones de los estudiantes de la especialidad de lengua extranjera: Inglés sobre atención a la diversidad en la formación inicial del profesorado de Educación Secundaria. Onomázein Rev. lingüística Filol. y traducción 2020, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilwell, B.; Diallo, K.; Zurn, P.; Vujicic, M. Migration of health-care workers from developing countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2004, 82, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasiorek, J.; van de Poel, K. Language-specific skills in intercultural healthcare communication: Comparing perceived preparedness and skills in nurses’ first and second languages. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 61, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. The challenges of public health, social work, and psychological counselling services in South Korea: The issues of limited support and resource. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese in UK Universities. Available online: http://bacsuk.org.uk/chinese-in-uk-universities (accessed on 17 October 2020).

- You, C.; Dörnyei, Z. Language learning motivation in China: Results of a large-scale stratified survey. Appl. Linguist. 2016, 37, 495–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Cervone, D. Self-evaluative and self-efficacy mechanisms governing the motivational effects of goal systems. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. The cultural cognitive development of personal beliefs and classroom behaviours of adult language instructors: A qualitative inquiry. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Social cognitive approach to career development: An overview. Career Dev. Q. 1996, 44, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Foreign language learning beyond English: The opportunities of One Belt, One Read (OBOR) Initiative. In Silk Road to Belt Road; Islam, N., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Recruitment and retention of international school teachers in remote archipelagic countries: The Fiji experience. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos santos, L.M. Becoming university language teachers in South Korea: The application of the interpretative phenomenological analysis and social cognitive career theory. J. Educ. e-Learning Res. 2020, 7, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. I teach nursing as a male nursing educator: The East Asian perspective, context, and social cognitive career experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayan, B. Students and teachers’ perceptions into the viability of mobile technology implementation to support language learning for first year business students in a Middle Eastern university. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 2017, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pavlova, L.; Vtorushina, Y. Developing students’ cognition culture for successful foreign language learning. SHS Web Conf. 2018, 50, 01128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. I want to become a registered nurse as a non-traditional, returning, evening, and adult student in a community college: A study of career-changing nursing students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.; Lent, R. Social cognitive career theory at 25: Progress in studying the domain satisfaction and career self-management models. J. Career Assess. 2019, 27, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. International school science teachers’ development and decisions under social cognitive career theory. Glob. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 22, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, J.; Abrams, M.D.; Tokar, D.M. An examination of the applicability of social cognitive career theory for African American college students. J. Career Assess. 2017, 25, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Developing bilingualism in nursing students: Learning foreign languages beyond the nursing curriculum. Healthcare 2021, 9, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Applications of Case Study Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, K.H.; Dos Santos, L.M. A brief discussion and application of interpretative phenomenological analysis in the field of health science and public health. Int. J. Learn. Dev. 2017, 7, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clandnin, D.; Connelly, F. Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.R. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Morbiato, A.; Arcodia, G.F.; Basciano, B. Topic and subject in Chinese and in the languages of Europe: Comparative remarks and implications for Chinese as a second/foreign language teaching. Chin. Second Lang. Res. 2020, 9, 31–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepermans, A. China’s 16 + 1 and Belt and Road Initiative in central and eastern Europe: Economic and political influence at a cheap price. J. Contemp. Cent. East. Eur. 2018, 26, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, L.Y.; O’Brien, K.M. The career development of Mexican American adolescent women: A test of social cognitive career theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2002, 49, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. The application of Chinese preventive medical treatments and activities: A qualitative collection of front-line traditional Chinese medicine doctors and medical professionals. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2019, 14, 5198–5202. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, L.; Lo, H.F. The development of doctoral degree curriculum in England: Perspectives from professional doctoral degree graduates. Int. J. Educ. Policy Leadersh. 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Ethnic Group: Facts and Figures. Available online: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/summaries/chinese-ethnic-group (accessed on 17 October 2020).

- Majumdar, B.; Browne, G.; Roberts, J.; Carpio, B. Effects of cultural sensitivity training on health care provider attitudes and patient outcomes. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2004, 36, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultsjö, S.; Bachrach-Lindström, M.; Safipour, J.; Hadziabdic, E. Cultural awareness requires more than theoretical education: Nursing students’ experiences. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 39, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, S.M. Cultural awareness workshops: Limitations and practical consequences. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Themes and Subthemes of This Study | ||

|---|---|---|

| Section 3.1. | Mandarin Chinese as one of the Strongest Languages for Global Development | |

| Section 3.1.1. | Personal Development and Potential International Promotion | |

| Section 3.2. | The Multitude of Mandarin Chinese-Speaking Patients | |

| Section 3.2.1. | Cultural Awareness of the Mandarin Chinese Language: Cultural Understanding and Practices Beyond Chinese People | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dos Santos, L.M. Upgrading Nursing Students’ Foreign Language and Communication Skills: A Qualitative Inquiry of the Afterschool Enhancement Programmes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105112

Dos Santos LM. Upgrading Nursing Students’ Foreign Language and Communication Skills: A Qualitative Inquiry of the Afterschool Enhancement Programmes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(10):5112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105112

Chicago/Turabian StyleDos Santos, Luis Miguel. 2021. "Upgrading Nursing Students’ Foreign Language and Communication Skills: A Qualitative Inquiry of the Afterschool Enhancement Programmes" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 10: 5112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105112

APA StyleDos Santos, L. M. (2021). Upgrading Nursing Students’ Foreign Language and Communication Skills: A Qualitative Inquiry of the Afterschool Enhancement Programmes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105112