Time-Varying Insomnia Symptoms and Incidence of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia among Older US Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database

2.2. Outcome Variables

2.3. Exposure Variable

2.4. Covariate Variables

2.5. Data Analysis

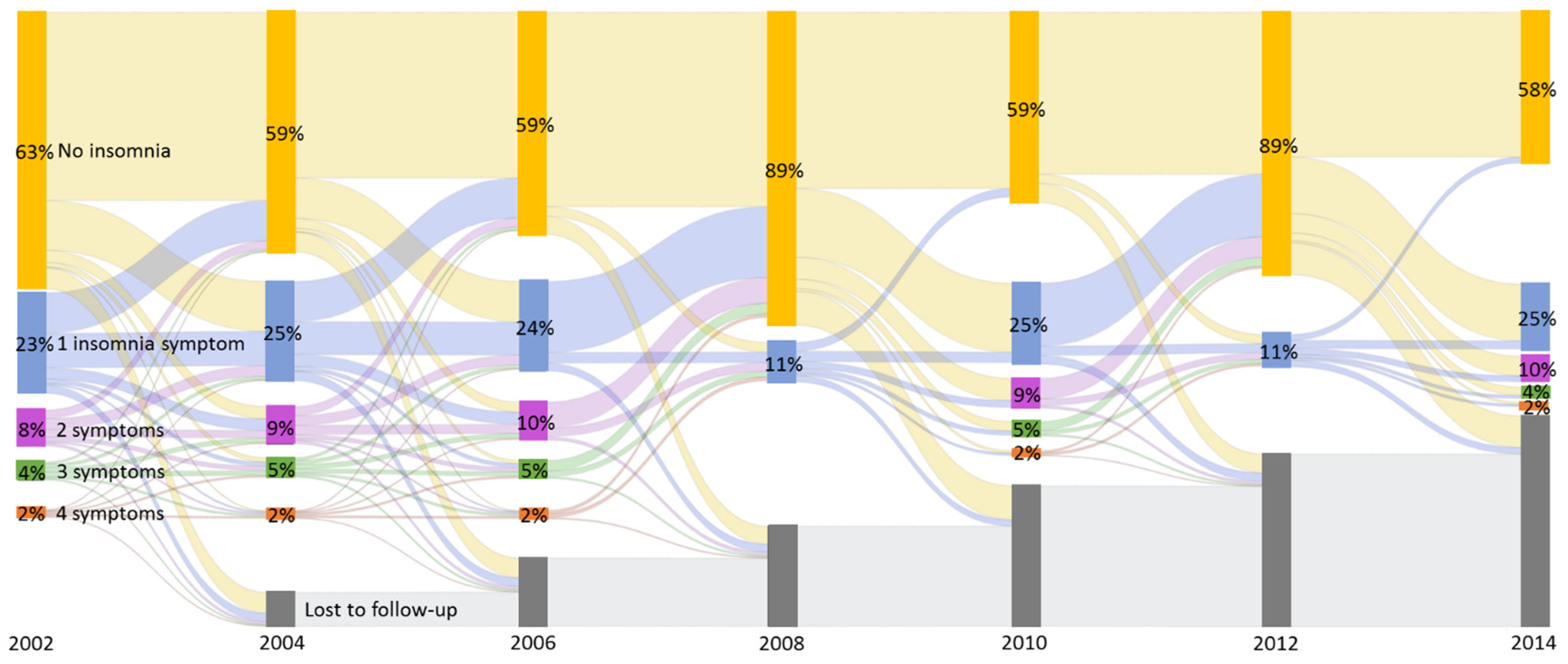

3. Results

3.1. Study Sample Characteristics

3.2. Cox Proportional Hazards Model with Time-Varying Insomnia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2018 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018, 14, 367–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, K.A.; Xu, W.; Gaglioti, A.H.; Holt, J.B.; Croft, J.B.; Mack, D.; McGuire, L.C. Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015–2060) in adults aged >/=65 years. Alzheimers Dement. 2019, 15, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2016, 12, 459–509. [Google Scholar]

- Plassman, B.L.; Langa, K.M.; Fisher, G.G.; Heeringa, S.G.; Weir, D.R.; Ofstedal, M.B.; Burke, J.R.; Hurd, M.D.; Potter, G.G.; Rodgers, W.L.; et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008, 148, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, R.C.; Caracciolo, B.; Brayne, C.; Gauthier, S.; Jelic, V.; Fratiglioni, L. Mild cognitive impairment: A concept in evolution. J. Intern. Med. 2014, 275, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, M.S.; DeKosky, S.T.; Dickson, D.; Dubois, B.; Feldman, H.H.; Fox, N.C.; Gamst, A.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.J.; Petersen, R.C.; et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011, 7, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguli, M.; Chang, C.C.H.; Snitz, B.E.; Saxton, J.A.; Vanderbilt, J.; Lee, C.W. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment by multiple classifications: The Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team (MYHAT) project. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 18, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.C.; Roberts, R.O.; Knopman, D.S.; Geda, Y.E.; Cha, R.H.; Pankratz, V.S.; Boeve, B.F.; Tangalos, E.G.; Ivnik, R.J.; Rocca, W.A. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment is higher in men. Mayo Clin. Study Aging Neurol. 2010, 75, 889–897. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, R.; Knopman, D.S. Classification and epidemiology of MCI. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2013, 29, 753–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, Y.E.S.; McLeland, J.S.; Toedebusch, C.D.; Xiong, C.; Fagan, A.M.; Duntley, S.P.; Morris, J.C.; Holtzman, D.M. Sleep quality and preclinical Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013, 70, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, C.S.; Wolk, A. The Role of Lifestyle Factors and Sleep Duration for Late-Onset Dementia: A Cohort Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 66, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, G.; Sommerlad, A.; Orgeta, V.; Costafreda, S.G.; Huntley, J.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 2017, 390, 2673–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.L.; Cadet, T.; Alcide, A.; O’Driscoll, J.; Maramaldi, P. Psychosocial risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease: The associative effect of depression, sleep disturbance, and anxiety. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 1577–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, A.S.; Kowgier, M.; Yu, L.; Buchman, A.S.; Bennett, D.A. Sleep Fragmentation and the Risk of Incident Alzheimer’s Disease and Cognitive Decline in Older Persons. Sleep 2013, 36, 1027–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutsey, P.L.; Misialek, J.R.; Mosley, T.H.; Gottesman, R.F.; Punjabi, N.M.; Shahar, E.; MacLehose, R.; Ogilvie, R.P.; Knopman, D.; Alonso, A. Sleep characteristics and risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2018, 14, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Chen, S.J.; Ma, M.Y.; Bao, Y.P.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y.M.; Shi, J.; Vitiello, M.V.; Lu, L. Sleep disturbances increase the risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2018, 40, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indi, S.; Kåreholt, I.; Johansson, L.; Skoog, J.; Sjöberg, L.; Wang, H.X.; Johansson, B.; Fratiglioni, L.; Soininen, H.; Solomon, A.; et al. Sleep disturbances and dementia risk: A multicenter study. Alzheimers Dement. 2018, 14, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar]

- Virta, J.J.; Heikkilä, K.; Perola, M.; Koskenvuo, M.; Räihä, I.; Rinne, J.O.; Kaprio, J. Midlife sleep characteristics associated with late life cognitive function. Sleep 2013, 36, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubu, O.M.; Brannick, M.; Mortimer, J.; Umasabor-Bubu, O.; Sebastião, Y.V.; Wen, Y.; Schwartz, S.; Borenstein, A.R.; Wu, Y.; Morgan, D.; et al. Sleep, Cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sleep 2017, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, R.S.; Pirraglia, E.; Agüera-Ortiz, L.F.; During, E.H.; Sacks, H.; Ayappa, I.; Walsleben, J.; Mooney, A.; Hussain, A.; Glodzik, L.; et al. Greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease in older adults with insomnia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y.; McEvoy, C.T.; Allen, I.E.; Yaffe, K. Association of Sleep-Disordered Breathing with Cognitive Function and Risk of Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2017, 74, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almondes, K.M.; Costa, M.V.; Malloy-Diniz, L.F.; Diniz, B.S. Insomnia and risk of dementia in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2016, 77, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Tan, C.C.; Zou, J.J.; Cao, X.P.; Tan, L. Sleep problems and risk of all-cause cognitive decline or dementia: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2019, 91, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardle-Pinkston, S.; Slavish, D.C.; Taylor, D.J. Insomnia and cognitive performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019, 48, 101205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ateia, J.M.; Nowell, P.D. Insomnia. Lancet 2004, 364, 1959–1973. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, N.E.; Carrier, J.; Postuma, R.B.; Gosselin, N.; Kakinami, L.; Thompson, C.; Chouchou, F.; Dang-Vu, T.T. Association between insomnia disorder and cognitive function in middle-aged and older adults: A cross-sectional analysis of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Sleep 2019, 42, zsz114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortier-Brochu, É.; Morin, C.M. Cognitive Impairment in Individuals with Insomnia: Clinical Significance and Correlates. Sleep 2014, 37, 1787–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.-M.; Li, Y.C.; Chen, H.J.; Lu, K.; Liang, C.L.; Liliang, P.C.; Tsai, Y.D.; Wang, K.W. Risk of dementia in patients with primary insomnia: A nationwide population-based case-control study. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, K.; Nettiksimmons, J.; Yesavage, J.; Byers, A. Sleep Quality and Risk of Dementia Among Older Male Veterans. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 23, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindi, S.; Johansson, L.; Skoog, J.; Mattsson, A.D.; Sjöberg, L.; Wang, H.X.; Fratiglioni, L.; Kulmala, J.; Soininen, H.; Solomon, A.; et al. Sleep disturbances and later cognitive status: A multi-centre study. Sleep Med. 2018, 52, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, D.; Monjan, A.; Masaki, K.; Ross, W.; Havlik, R.; White, L.; Launer, L. Daytime sleepiness is associated with 3-year incident dementia and cognitive decline in older Japanese-American men. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2001, 49, 1628–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, S.L.; Hu, T.; Spadola, C.E.; Li, T.; Naseh, M.; Burgess, A.; Cadet, T. Mild cognitive impairment: Associations with sleep disturbance, apolipoprotein e4, and sleep medications. Sleep Med. Res. 2018, 52, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health and Retirement Study (HRS). The Health and Retirement Study. 2019. Available online: https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/about (accessed on 22 November 2019).

- Ofstedal, M.B.; Fisher, G.G.; Herzog, A.R.; Wallace, R.B.; Weir, D.R.; Langa, K.M. HRS/AHEAD Documentation Report. Documentation of Cognitive Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study. 2005. Available online: https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/sites/default/files/biblio/dr-006.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Crimmins, E.M.; Kim, J.K.; Langa, K.M.; Weir, D.R. Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: The Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2011, 66 (Suppl. 1), i162–i171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leggett, A.N.; Sonnega, A.J.; Lohman, M.C. The association of insomnia and depressive symptoms with all-cause mortality among middle-aged and old adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaussent, I.; Bouyer, J.; Ancelin, M.L.; Berr, C.; Foubert-Samier, A.; Ritchie, K.; Ohayon, M.M.; Besset, A.; Dauvilliers, Y. Excessive sleepiness is predictive of cognitive decline in the elderly. Sleep 2012, 35, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P.K.; Gill, R.D. Cox’s regression model for counting processes: A large sample study. Ann. Stat. 1982, 10, 1100–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysen, T.S.; Wolters, F.J.; Luik, A.I.; Ikram, M.K.; Tiemeier, H.; Ikram, M.A. Subjective Sleep Quality is not Associated with Incident Dementia: The Rotterdam Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 64, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.J.; Espie, C.A.; Hunt, K.; Benzeval, M. The longitudinal course of insomnia symptoms: Inequalities by sex and occupational class among two different age cohorts followed for 20 years in the west of Scotland. Sleep 2012, 35, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlis, M.; Gehrman, P.; Ellis, J. The natural history of insomnia: What we know, don’t know, and need to know. Sleep Med. Res. 2011, 2, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.M.; Lin, S.C.; Cheng, C.P. Transient insomnia versus chronic insomnia: A comparison study of sleep-related psychological/behavioral characteristics. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 69, 1094–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research. Extent and Health Consequences of Chronic Sleep Loss and Sleep Disorders: An Unmet Public Health Problem; Colten, H., Altenvogt, B., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, E.Y. Structural brain neuroimaging in primary insomnia. Sleep Med. Res. 2015, 6, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, E.Y.; Kim, H.; Suh, S.; Hong, S.B. Hippocampal substructural vulnerability to sleep disturbance and cognitive impairment in patients with chronic primary insomnia: Magnetic resonance imaging morphometry. Sleep 2014, 37, 1189–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, N.E.; Lagopoulos, J.; Duffy, S.L.; Cockayne, N.L.; Hickie, I.B.; Lewis, S.J.; Naismith, S.L. Sleep quality in healthy older people: Relationship with (1)H magnetic resonance spectroscopy markers of glial and neuronal integrity. Behav. Neurosci. 2013, 127, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, M.K.; Mestre, H.; Nedergaard, M. The glymphatic pathway in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Kang, H.; Xu, Q.; Chen, M.J.; Liao, Y.; Thiyagarajan, M.; O’Donnell, J.; Christensen, D.J.; Nicholson, C.; Iliff, J.J.; et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science 2013, 342, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, Y.E.; Lucey, B.P.; Holtzman, D.M. Sleep and Alzheimer disease pathology--a bidirectional relationship. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 10, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozzini, L.; Conti, M.Z.; Riva, M.; Ceraso, A.; Caratozzolo, S.; Zanetti, M.; Padovani, A. Non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment and sleep complaints: A bidirectional relationship? Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, B.; Sorbi, S. Sleep and Cognitive Decline: A Strong Bidirectional Relationship. It Is Time for Specific Recommendations on Routine Assessment and the Management of Sleep Disorders in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Eur. Neurol. 2015, 74, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Baseline Characteristics | Total Sample N = 13,833 |

|---|---|

| Baseline insomnia (SD) | 0.58 (0.92) |

| Age mean (SD) | 66.41 (9.52) |

| Gender (% Female) | 59.37% |

| Race (% White) | 86.29% |

| Education (% Less than high school) | 17.25% |

| BMI mean (SD) | 27.38 (5.30) |

| Drinks per day (SD) | 0.63 (0.01) |

| Smoking status (%Smoker) | 14.13 |

| Chronic disease Index (% No Chronic illness) | 19.45 |

| Mild Cognitive Impairment | Dementia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted * | Unadjusted | Adjusted * | ||

| Insomnia | 1.10 ^ (1.09–1.11) | 1.05 ^ (1.04–1.06) | 1.09 ^ (1.07–1.10) | 1.05 ^ (1.03–1.06) | |

| Age (Years) | 1.06 ^ (1.06–1.06) | 1.11 ^ (1.11–1.11) | |||

| Education | |||||

| Less than High School | 3.60 ^ (3.59–3.60) | 2.67 ^ (2.66–2.68) | |||

| GED | 2.42 ^ (2.42–2.43) | 1.84 ^ (1.83–1.84) | |||

| High School Graduate | 2.03 ^ (2.02–2.03) | 1.48 ^ (1.47–1.48) | |||

| Some College | 1.53 ^ (1.53–1.53) | 1.19 ^ (1.19–1.20) | |||

| College and Above | Ref | Ref | |||

| Race | White | Ref | Ref | ||

| Black | 1.95 ^ (1.95–1.95) | 2.09 ^ (2.08–2.10) | |||

| Other | 1.62 ^ (1.61–1.62) | 1.61 ^ (1.60–1.62) | |||

| Gender | Male | Ref | Ref | ||

| Female | 0.81 ^ (0.81–0.81) | 0.98 ^ (0.98–0.98) | |||

| Smoking | No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1.25 ^ (1.24–1.25) | 1.36 ^ (1.36–1.37) | |||

| BMI | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.98 ^ (0.98–0.98) | |||

| Number of Chronic Diseases | 1.08 ^ (1.08–1.08) | 1.59 ^ (1.59–1.59) | |||

| Number of Drinks | 0.96 ^ (0.96–0.96) | 0.91 ^ (0.91–0.92) | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Resciniti, N.V.; Yelverton, V.; Kase, B.E.; Zhang, J.; Lohman, M.C. Time-Varying Insomnia Symptoms and Incidence of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia among Older US Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010351

Resciniti NV, Yelverton V, Kase BE, Zhang J, Lohman MC. Time-Varying Insomnia Symptoms and Incidence of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia among Older US Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(1):351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010351

Chicago/Turabian StyleResciniti, Nicholas V., Valerie Yelverton, Bezawit E. Kase, Jiajia Zhang, and Matthew C. Lohman. 2021. "Time-Varying Insomnia Symptoms and Incidence of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia among Older US Adults" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 1: 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010351

APA StyleResciniti, N. V., Yelverton, V., Kase, B. E., Zhang, J., & Lohman, M. C. (2021). Time-Varying Insomnia Symptoms and Incidence of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia among Older US Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010351