Root Cause Analysis to Identify Medication and Non-Medication Strategies to Prevent Infection-Related Hospitalizations from Australian Residential Aged Care Services

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Setting

2.2. Identification of Events

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Root Cause Identification

2.5. Recommendation Generation

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sloane, P.D.; Zimmerman, S.; Nace, D.A. Progress and challenges in the management of nursing home infections. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, J.C.; Flicker, L.; Mackenzie, E.; Jacobs, I.G.; Fatovich, D.; Drummond, S.; Harris, M.; Holman, D.C.D.J.; Sprivulis, P. Interface between residential aged care facilities and a teaching hospital emergency department in Western Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2006, 184, 432–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, K.; Jansen, K.; Grimsmo, A.; Eide, G.E.; Geitung, J.T. Hospital admissions from nursing homes: Rates and reasons. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2011, 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalic, S.; Sluggett, J.K.; Ilomaki, J.; Wimmer, B.C.; Tan, E.C.; Robson, L.; Emery, T.; Bell, J.S. Polypharmacy and medication regimen complexity as risk factors for hospitalization among residents of long-term care facilities: A prospective cohort study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 1067.e1–1067.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouslander, J.G.; Lamb, G.; Perloe, M.; Givens, J.H.; Kluge, L.; Rutland, T.; Atherly, A.; Saliba, D. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations of nursing home residents: Frequency, causes, and costs: [see editorial comments by Drs. Jean F. Wyman and William R. Hazzard, pp 760–761]. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sluggett, J.K.; Ilomaki, J.; Seaman, K.L.; Corlis, M.; Bell, J.S. Medication management policy, practice and research in Australian residential aged care: Current and future directions. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 116, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Johnson, S.A.; Richards, M.J.; Smith, M.A.; Worth, L.J. Infections in Australian aged-care facilities: Evaluating the impact of revised McGeer criteria for surveillance of urinary tract infections. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiology 2016, 37, 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, A.; Mody, L. Common infections in nursing homes: A review of current issues and challenges. Aging Health 2011, 7, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, D.C.; O’Malley, A.J.; Barhydt, N.R. The costs and potential savings associated with nursing home hospitalizations. Health Aff. 2007, 26, 1753–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, D.; Kington, R.; Buchanan, J.; Bell, R.; Wang, M.; Lee, M.; Herbst, M.; Lee, D.; Sur, D.; Rubenstein, L. Appropriateness of the decision to transfer nursing facility residents to the hospital. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2000, 48, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, S.E. The relationship between antimicrobial resistance and patient outcomes: Mortality, length of hospital stay, and health care costs. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 42, S82–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.J.; Cheng, A.C.; Kennon, J.; Spelman, D.; Hale, D.; Melican, G.; Sidjabat, H.E.; Paterson, D.L.; Kong, D.C. Prevalence of multidrug-resistant organisms and risk factors for carriage in long-term care facilities: A nested case-control study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 1972–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, M.; Dick, A.W.; Sorbero, M.; Mody, L.; Stone, P.W. Changes in US nursing home infection prevention and control programs from 2014 to 2018. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.N.; Bell, J.S.; Chen, E.Y.H.; Gilmartin-Thomas, J.F.M.; Ilomäki, J. Medications and prescribing patterns as factors associated with hospitalizations from long-term care facilities: A systematic review. Drugs Aging 2018, 35, 423–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hocine, M.N.; Temime, L. Impact of hand hygiene on the infectious risk in nursing home residents: A systematic review. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2015, 43, e47–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jump, R.L.P.; Crnich, C.J.; Mody, L.; Bradley, S.F.; Nicolle, L.E.; Yoshikawa, T.T. Infectious diseases in older adults of long-term care facilities: Update on approach to diagnosis and management. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government: Department of Social Services. Prevention and Control of Infection in Residential and Community Aged Care. 2013. Available online: https://agedcare.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/01_2015/infection_control_booklet_-_december_2014.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Ouslander, J.G.; Naharci, I.; Engstrom, G.; Shutes, J.; Wolf, D.G.; Alpert, G.; Rojido, C.; Tappen, R.; Newman, D. Root cause analyses of transfers of skilled nursing facility patients to acute hospitals: Lessons learned for reducing unnecessary hospitalizations. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, M.; Pogorzelska-Maziarz, M.; Smith, P.W.; Larson, E. Infection prevention in long-term care: A systematic review of randomized and nonrandomized trials. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meddings, J.; Saint, S.; Krein, S.L.; Gaies, E.; Reichert, H.; Hickner, A.; McNamara, S.; Mann, J.D.; Mody, L. Systematic review of interventions to reduce urinary tract infection in nursing home residents. J. Hosp. Med. 2017, 12, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Antimicrobial Stewardship in Australian Health Care. 2018. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/healthcare-associated-infection/antimicrobial-stewardship/book/ (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Australian Government: Department of Health of Ageing. Gastro-Info: Outbreak Coordinator’s Handbook. 2015. Available online: https://agedcare.health.gov.au/ageing-and-aged-care-publications-and-articles-training-and-learning-resources-gastro-info-gastroenteritis-kit-for-aged-care/gastro-info-outbreak-coordinators-handbook (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Sjogren, P.; Nilsson, E.; Forsell, M.; Johansson, O.; Hoogstraate, J. A systematic review of the preventive effect of oral hygiene on pneumonia and respiratory tract infection in elderly people in hospitals and nursing homes: Effect estimates and methodological quality of randomized controlled trials. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 2124–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, S. Strategies to improve outcomes in nursing home residents with modifiable risk factors for respiratory tract infections. PA Patient Saf. Advis. 2011, 8, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Poscia, A.; Collamati, A.; Carfi, A.; Topinkova, E.; Richter, T.; Denkinger, M.; Pastorino, R.; Landi, F.; Ricciardi, W.; Bernabei, R.; et al. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in older adults living in nursing home: A survival analysis on the shelter study. Eur J. Public Health 2017, 27, 1016–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frentzel, E.; Jump, R.L.P.; Archbald-Pannone, L.; Archbald-Pannone, L.; Nace, D.A.; Schweon, S.J.; Gaur, S.; Naqvi, F.; Pandya, N.; Mercer, W. Infection Advisory Subcommittee of AMDA. Recommendations for mandatory influenza vaccinations for health care personnel from AMDA’s infection advisory subcommittee. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 25–28.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooney, J.J.; Vanden Heuvel, L.N. Root cause analysis for beginners. Quality Progress. 2004, 37, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Government of South Australia: SA Health. Root Cause Analysis (RCA). Available online: https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/clinical+resources/safety+and+quality/governance+for+safety+and+quality/root+cause+analysis+rca (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Australian Goverment. Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission. Guidance and Resources for Providers to support the Aged Care Quality Standards. Australian Government Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

- Ouslander, J.G.; Bonner, A.; Herndon, L.; Shutes, J. The Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) quality improvement program: An overview for medical directors and primary care clinicians in long term care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sluggett, J.K.; Lalic, C.; Hosking, S.M.; Ilomӓki, J.; Shortt, T.; McLoughlin, J.; Yu, S.; Cooper, T.; Robson, L.; Van Dyk, E.; et al. Root cause analysis of fall-related hospitalisations among residents of aged care services. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.C.; Visvanathan, R.; Hilmer, S.N.; Vitry, A.; Quirke, T.; Emery, T.; Robson, L.; Shortt, T.; Sheldrick, S.; Lee, S. Analgesic use, pain and daytime sedation in people with and without dementia in aged care facilities: A cross-sectional, multisite, epidemiological study protocol. BMJ Open 2014, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ahmet, A.; Ward, L.; Krishnamoorthy, P.; Mandelcorn, E.D.; Leigh, R.; Brown, J.; Cohen, A.; Kim, H. A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2013, 9, Article 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.B.; Dmochowski, R.R.; Sand, P.K.; Macdiarmid, S. Safety and tolerability of extended-release oxybutynin once daily in urinary incontinence: Combined results from two phase 4 controlled clinical trials. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2007, 39, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.A.; Gaines, T.; LaGuardia, K.D. Extended-Release Oxybutynin Therapy for VMS Study Group. Extended-release oxybutynin therapy for vasomotor symptoms in women: A randomized clinical trial. Menopause 2016, 23, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, C. Serious infection during etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: A literature review. Int J. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 19, 536–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, J.; Ogston, S.; Foerster, J. Safety and efficacy of methotrexate in psoriasis: A meta-analysis of published trials. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifan, A.; Stanciu, C.; Girleanu, I.; Stoica, O.C.; Singeap, A.M.; Maxim, R.; Chiriac, S.A.; Ciobica, A.; Boiculese, L. Proton pump inhibitors therapy and risk of Clostridium difficile infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 6500–6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latino, R.J.; Flood, A. Optimizing FMEA and RCA efforts in health care. J. Healthc. Risk Manag. 2004, 24, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haxby, E.; Shuldham, C. How to undertake a root cause analysis investigation to improve patient safety. Nurs. Stand. 2018, 32, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, R.L.; Isherwood, L.; Ben-Tovim, D. Why do older people with multi-morbidity experience unplanned hospital admissions from the community: A root cause analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liapikou, A.; Polverino, E.; Cilloniz, C.; Community-Acquired Pneumonia Organization (CAPO) Investigators. A worldwide perspective of nursing home-acquired pneumonia compared with community-acquired pneumonia. Respir. Care 2014, 59, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cao, Y.; Lin, J.; Ng, L.; Needleman, I.; Walsh, T.; Li, C. Oral care measures for preventing nursing home-acquired pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 9, Cd012416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Bradford, J.M.; Bull, A.L.; Worth, L.J. Infection prevention quality indicators in aged care: Ready for a national approach. Aust. Health Rev. 2019, 43, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs Slifka, K.M.; Kabbani, S.; Stone, N.D. Prioritizing prevention to combat multidrug resistance in nursing homes: A call to action. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumyati, G.; Stone, N.D.; Nace, D.A.; Crnich, C.J.; Jump, R.L. Challenges and strategies for prevention of multidrug-resistant organism transmission in nursing homes. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2017, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huebner, C.; Roggelin, M.; Flessa, S. Economic burden of multidrug-resistant bacteria in nursing homes in Germany: A cost analysis based on empirical data. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e008458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.R.; Cho, I.H.; Jeong, B.C.; Lee, S.H. Strategies to minimize antibiotic resistance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 4274–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.J.; Stuart, R.L.; Kong, D.C. Antibiotic use in residential aged care facilities. Aust. Fam Physician 2015, 44, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Reform of Requirements for Long-Term Care Facilities. 2016. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/10/04/2016-23503/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-reform-of-requirements-for-long-term-care-facilities (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Aged Care National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey Report. 2017. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/2017-acNAPS.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- McGeer, A.; Campbell, B.; Emori, T.G.; Hierholzer, W.J.; Jackson, M.M.; Nicolle, L.E.; Peppier, C.; Rivera, A.; Schollenberger, D.G.; Simor, A.E.; et al. Definitions of infection for surveillance in long-term care facilities. Am. J. Infect. Control 1991, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peron, E.P.; Hirsch, A.A.; Jury, L.A.; Jump, R.L.; Donskey, C.J. Another setting for stewardship: High rate of unnecessary antimicrobial use in a veterans affairs long-term care facility. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 289–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Hou, X.Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, J.; Sun, J.; Dingle, K.D.; Purtill, R.; Tapp, S.; Lukin, B. Hospital in the nursing home program reduces emergency department presentations and hospital admissions from residential aged care facilities in Queensland, Australia: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalto, M.; Chu, M.Y.; Ratnam, I.; Spelman, T.; Thursky, K. The treatment of nursing home-acquired pneumonia using a medically intensive hospital in the home service. Med. J. Aust. 2015, 203, 441–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Gonski, P.N.; Jarick, J.; Frese, S.; Gerrard, S. Southcare Geriatric Flying Squad: An innovative Australian model providing acute care in residential aged care facilities. Intern. Med. J. 2018, 48, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hullick, C.; Conway, J.; Higgins, I.; Hewitt, J.; Dilworth, S.; Holliday, E.; Attia, J. Emergency department transfers and hospital admissions from residential aged care facilities: A controlled pre-post design study. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolland, Y.; Mathieu, C.; Piau, C.; Cayla, F.; Bouget, C.; Vellas, B.; Barreto, P.D.S. Improving the quality of care of long-stay nursing home residents in France. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, S.; Lawand, C. A snapshot of advance directives in long-term care: How often is “do not” done? Healthc Q. 2017, 19, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peerally, M.F.; Carr, S.; Waring, J.; Dixon-Woods, M. The problem with root cause analysis. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2017, 26, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

| Characteristic | N (%) or Median (Interquartile Range) |

|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 86 (82–92) |

| Female | 32 (65.3) |

| Medical conditions Dementia Diabetes Asthma Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Ischemic heart disease Heart failure Prior stroke | 10 (20.4) 16 (32.7) 8 (16.3) 17 (34.7) 16 (32.7) 19 (38.8) 7 (14.3) |

| Current smoker | 2 (4.1) |

| Indwelling catheter | 6 (12.2) |

| History of infection in the previous 6 months | 15 (30.6) |

| Advance care directive in place prior to hospitalization | 34 (69.4) |

| Medication use a Polypharmacy (≥9 regular medications) b Charted regular medications that may increase infection risk b Influenza vaccination prescribed by GP on the RACS medication chart and documented as administered c | 32 (71.1) 9 (20.0) 11 (24.4) |

| Characteristic | N (%) (n = 49) |

|---|---|

| Infection type Respiratory infection Pneumonia Exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Urinary infection Urinary tract infection Urosepsis Hospitalizations for urinary infection where an indwelling catheter was present Skin infection Cellulitis Other | 29 (59.2) 12 (24.5) 5 (10.2) 14 (28.6) 7 (14.3) 6 (12.2) 2 (4.1) 5 (10.2) 3 (6.1) 4 (8.2) |

| New or worsening signs or symptoms in the 2 weeks prior to hospital transfer Feeling unwell Altered mental status or changes in behavior Malaise, lethargy, drowsiness, or refusal to get out of bed Functional decline Fall New or worsening pain Fever, chills, or rigors Decreased oral intake Nausea or vomiting New/increasing abdominal pain or diarrhea | 15 (30.6) 7 (14.3) 13 (26.5) 9 (18.4) 7 (14.3) 17 (34.7) 7 (14.3) 10 (20.4) 13 (26.5) 8 (17.0) |

| Testing undertaken within the RACS in the 2 weeks prior to hospital transfer a Blood test Urinary dipstick or urinalysis Other Radiology No testing undertaken | 8 (17.0) 13 (26.5) 3 (6.4) 0 (0.0) 29 (61.7) |

| Interventions undertaken within the RACS from the time the condition was first suspected until hospital transfer Monitor vital signs New or change in medication(s) Oxygen Physiotherapy review/treatment Other None required | 40 (81.6) 27 (55.1) 22 (44.9) 3 (6.1) 5 (10.2) 3 (6.1) |

| External provider evaluation of the resident Usual GP or GP from same practice Locum GP Nurse Practitioner Extended care paramedic Resident’s condition discussed with GP or locum via telephone Nil documented | 27 (55.1) 13 (26.5) 1 (2.0) 5 (10.2) 5 (10.2) 6 (12.2) |

| Antimicrobial use in the 2 weeks prior to hospital transfer b Penicillin Cephalosporin Macrolide Trimethoprim or nitrofurantoin Oseltamivir | 17 (37.8) 9 (20.0) 5 (11.1) 5 (11.1) 4 (8.9) 2 (4.4) |

| Person authorizing hospital transfer Usual GP or GP from same practice Locum GP Nurse practitioner Registered nurse Resident or family member Extended care paramedic | 13 (26.5) 8 (16.3) 2 (4.1) 19 (38.8) 4 (8.2) 3 (6.1) |

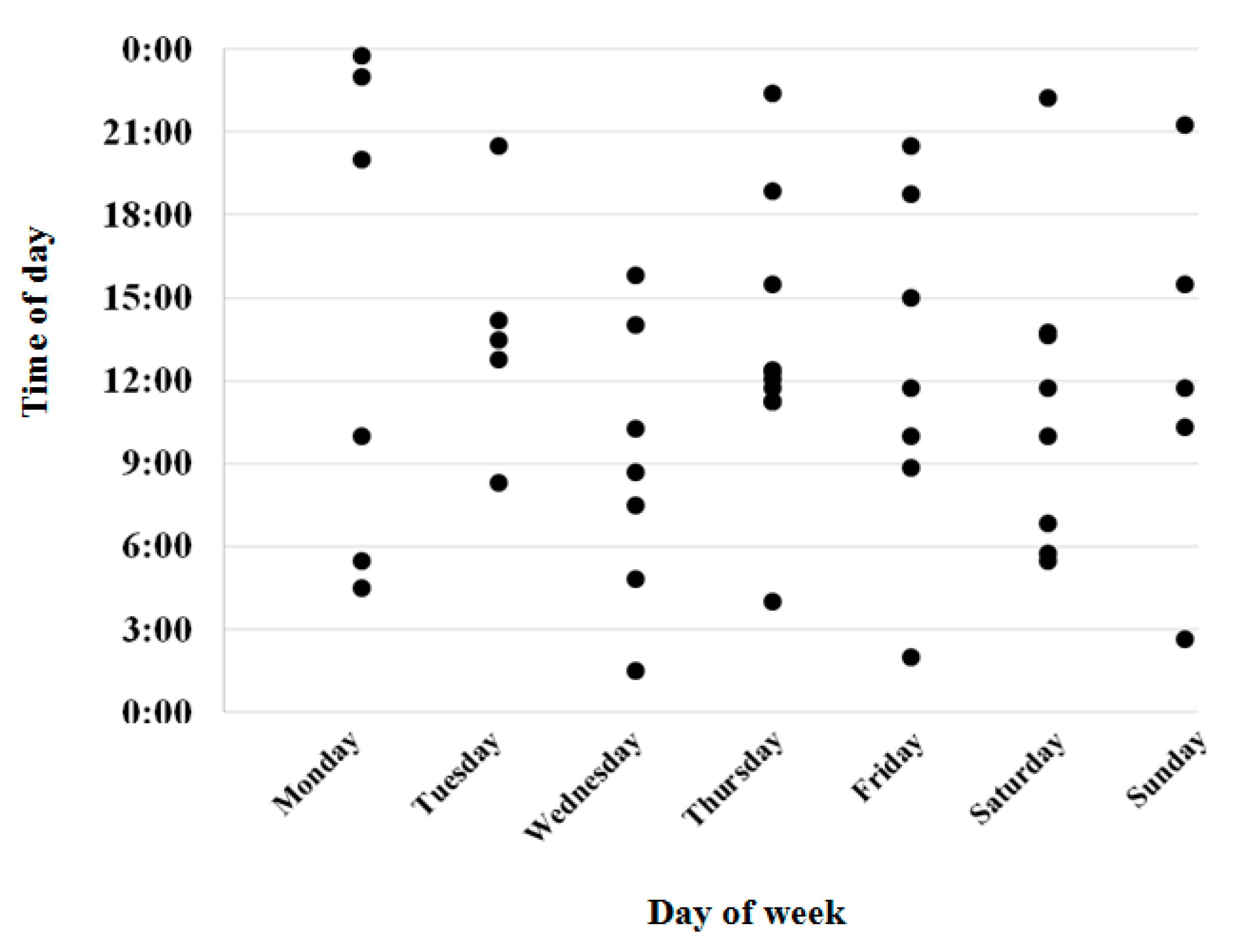

| Day of hospital transfer Weekday (Monday–Friday) Weekend (Saturday–Sunday) | 36 (73.5) 13 (26.5) |

| Time of hospital transfer Between 07:00 and 14:59 Between 15:00 and 22:59 Between 23:00 and 06:59 | 24 (49.0) 13 (26.5) 12 (24.5) |

| Domain | Factors Contributing to Infection-Related Hospitalizations Identified through the Root Cause Analysis | Potential Strategies to Mitigate Risk of Infection-Related Hospitalizations |

|---|---|---|

| Resident assessment |

|

|

| Staff training and resident factors |

|

|

| Equipment and work environment |

|

|

| Information, policies, and procedures |

|

|

| Communication and coordination |

|

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sluggett, J.K.; Lalic, S.; Hosking, S.M.; Ritchie, B.; McLoughlin, J.; Shortt, T.; Robson, L.; Cooper, T.; Cairns, K.A.; Ilomäki, J.; et al. Root Cause Analysis to Identify Medication and Non-Medication Strategies to Prevent Infection-Related Hospitalizations from Australian Residential Aged Care Services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093282

Sluggett JK, Lalic S, Hosking SM, Ritchie B, McLoughlin J, Shortt T, Robson L, Cooper T, Cairns KA, Ilomäki J, et al. Root Cause Analysis to Identify Medication and Non-Medication Strategies to Prevent Infection-Related Hospitalizations from Australian Residential Aged Care Services. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(9):3282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093282

Chicago/Turabian StyleSluggett, Janet K., Samanta Lalic, Sarah M. Hosking, Brett Ritchie, Jennifer McLoughlin, Terry Shortt, Leonie Robson, Tina Cooper, Kelly A. Cairns, Jenni Ilomäki, and et al. 2020. "Root Cause Analysis to Identify Medication and Non-Medication Strategies to Prevent Infection-Related Hospitalizations from Australian Residential Aged Care Services" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 9: 3282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093282

APA StyleSluggett, J. K., Lalic, S., Hosking, S. M., Ritchie, B., McLoughlin, J., Shortt, T., Robson, L., Cooper, T., Cairns, K. A., Ilomäki, J., Visvanathan, R., & Bell, J. S. (2020). Root Cause Analysis to Identify Medication and Non-Medication Strategies to Prevent Infection-Related Hospitalizations from Australian Residential Aged Care Services. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093282