Association between Living with Children and the Health and Health Behavior of Women and Men. Are There Differences by Age? Results of the “German Health Update” (GEDA) Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. State of Research

1.2. Aim of the Study

- Are there differences in the health and health behavior of women and men according to parental status (living with children)?

- Does the association between health/health behavior and parental status in women and men vary with age?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

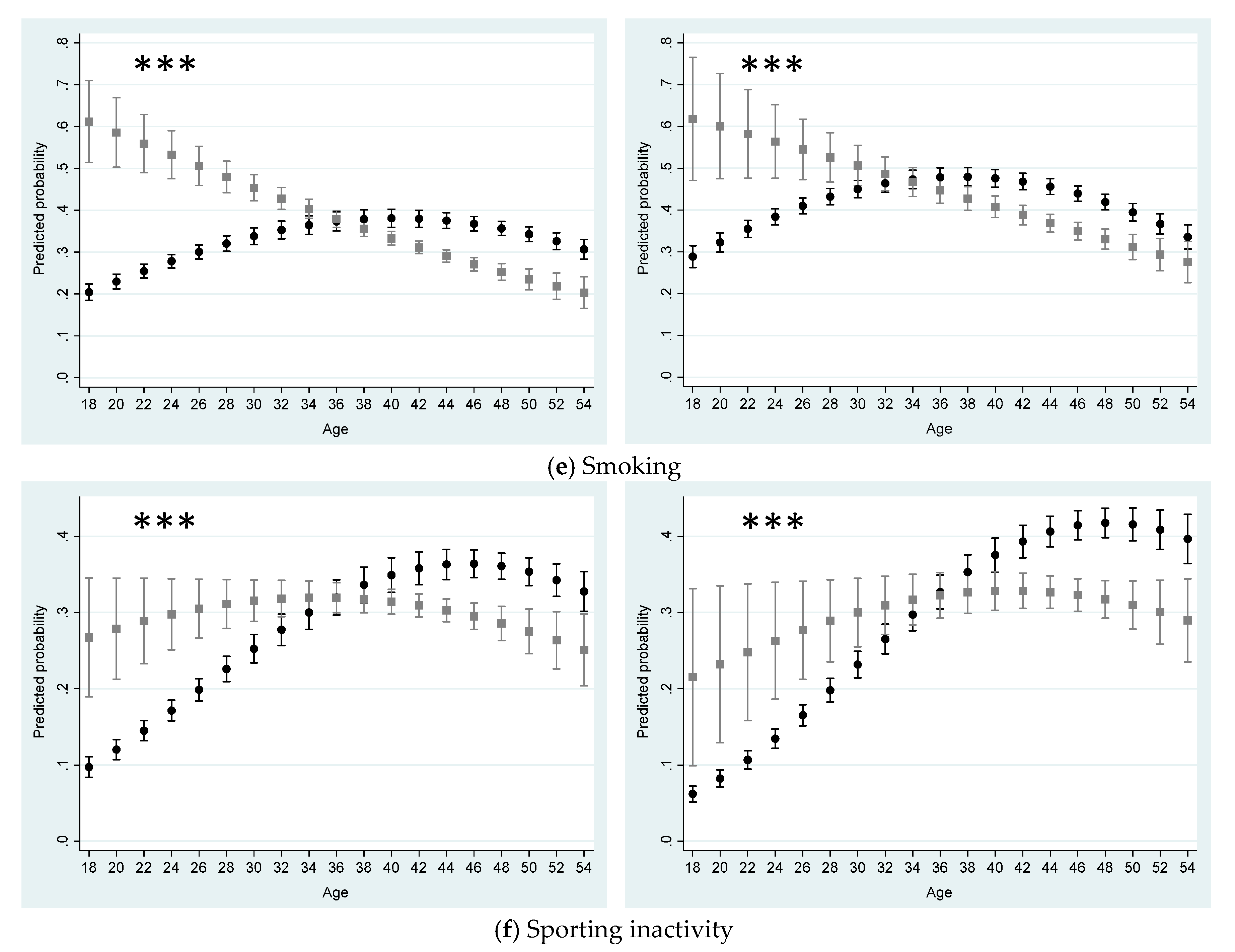

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nomaguchi, K.M.; Milkie, M.A. Costs and rewards of children: The effects of becoming a parent on adults’ lives. J. Marriage Fam. 2003, 65, 356–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hank, K.; Steinbach, A. Families and Health: A Review. In A Demographic Perspective on Gender, Family and Health in Europe; Doblhammer, G., Gumà, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Nomaguchi, K.; Milkie, M.A. Parenthood and well-being: A decade in review. J. Marriage Fam. 2020, 82, 198–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMunn, A.; Bartley, M.; Hardy, R.; Kuh, D. Life course social roles and women’s health in mid-life: Causation or selection? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fokkema, T. Combining a job and children: Contrasting the health of married and divorced women in the Netherlands? Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 54, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, B.; Baxter, J.; Western, M. Family, work and health: The impact of marriage, parenthood and employment on self-reported health of Australian men and women. J. Sociol. 2006, 42, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlat, M.; Sermet, C.; Le Pape, A. Women’s health in relation with their family and work roles: France in the early 1990s. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 50, 1807–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostiainen, E.; Martelin, T.; Kestilä, L.; Martikainen, P.; Koskinen, S. Employee, partner, and mother: Woman’s three roles and their implications for health. J. Fam Issues 2009, 30, 1122–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahelma, E.; Arber, S.; Kivelä, K.; Roos, E. Multiple roles and health among British and Finnish women: The influence of socioeconomic circumstances. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 54, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, E.; Burström, B.; Saastamoinen, P.; Lahelma, E. A comparative study of the patterning of women’s health by family status and employment status in Finland and Sweden. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 2443–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Lippe, E.; Rattay, P. Association of partner, parental, and employment statuses with self-rated health among German women and men. SSM Popul. Health 2016, 2, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Floderus, B.; Hagman, M.; Aronsson, G.; Marklund, S.; Wikman, A. Self-reported health in mothers: The impact of age, and socioeconomic conditions. Women Health 2008, 47, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namkung, E.H.; Mitra, M.; Nicholson, J. Do disability, parenthood, and gender matter for health disparities? A US population-based study. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, C.E. Gender differences in the social and economic burdens of parenting and psychological distress. J. Marriage Fam. 1997, 59, 809–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bures, R.M.; Koropeckyj-Cox, T.; Loree, M. Childlessness, parenthood, and depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older adults. J. Fam. Issues 2009, 30, 670–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, R.J.; Simon, R.W. Clarifying the relationship between parenthood and depression. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2005, 46, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Holton, S.; Fisher, J.; Rowe, H. Motherhood: Is it good for women’s mental health? J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2010, 28, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbig, S.; Lampert, T.; Klose, M.; Jacobi, F. Is parenthood associated with mental health? Findings from an epidemiological community survey. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006, 41, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalucza, S.; Hammarström, A.; Nilsson, K. Mental health and parenthood—A longitudinal study of the relationship between self-reported mental health and parenthood. Health Sociol. Rev. 2015, 24, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirowsky, J.; Ross, C.E. Depression, parenthood, and age at first birth. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 54, 1281–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaisier, I.; Beekman, A.T.F.; De Bruijn, J.G.M.; De Graaf, R.; Ten Have, M.; Smit, J.H.; van Dyck, R.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. The effect of social roles on mental health: A matter of quantity or quality? J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 111, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudrovska, T. Psychological implications of motherhood and fatherhood in midlife: Evidence from sibling models. J. Marriage Fam. 2008, 70, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöbel-Richter, Y.; Brähler, E.; Zenger, M. Lebenszufriedenheit und psychische Gesundheit von Müttern und Nichtmüttern im Vergleich. Repräsentative Ergebnisse [Life satisfaction and mental health of mothers and non-mothers compared. Representative results]. In Was sagen die Mütter? Qualitative und quantitative Forschung rund um Schwangerschaft, Geburt und Wochenbett [What do the mothers say? Qualitative and quantitative research on pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium]; Makowsky, K., Schücking, B., Eds.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Basel, Germany, 2013; pp. 305–324. [Google Scholar]

- Giesselmann, M. Mutterschaft geht häufig mit verringertem mentalem Wohlbefinden einher [Motherhood is often associated with reduced mental well-being]. DIW Wochenber. Nr. 35 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, L.; Hockey, R.; Ware, R.S.; Lee, C. Mental health-related quality of life and the timing of motherhood: A 16-year longitudinal study of a national cohort of young Australian women. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastian, L.A.; West, N.A.; Corcoran, C.; Munger, R.G. Number of children and the risk of obesity in older women. Prev. Med. 2005, 40, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berge, J.; Larson, N.; Bauer, K.W.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Are parents of young children practicing healthy nutrition and physical activity behaviors? Pediatrics 2011, 127, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, W.; Hockey, R.; Dobson, A. Effects of having a baby on weight gain. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 38, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.; Trost, S.G. Life transitions and changing physical activity patterns in young women. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2003, 25, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, V. Changes in health-related behaviours and cardiovascular risk factors in young adults: Associations with living with a partner. Prev. Med. 2004, 39, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, C.F.; Duncan, G.; Gutina, A.; Rutsohn, J.; McDade, T.W.; Adam, E.K.; Coley, R.L.; Chase-Lansdale, P.L. Longitudinal study of body mass index in young males and the transition to fatherhood. Am. J. Men’s Health 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Syrda, J. The impact of marriage and parenthood on male body mass index: Static and dynamic effects. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 186, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bellows-Riecken, K.H.; Rhodes, R.E. A birth of inactivity? A review of physical activity and parenthood. Prev. Med. 2008, 46, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, E.E.; Rofey, D.L.; Robertson, R.J.; Nagle, E.F.; Otto, A.D.; Aaron, D.J. Influence of marriage and parenthood on physical activity: A 2-year prospective analysis. J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perales, F.; Del Pozo-Cruz, J.; Cruz, B.D.P. Long-term dynamics in physical activity behaviour across the transition to parenthood. Int. J. Public Health 2015, 60, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pot, N.; Keizer, R. Physical activity and sport participation: A systematic review of the impact of fatherhood. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 4, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laroche, H.; Wallace, R.B.; Snetselaar, L.; Hillis, S.; Cai, X.; Steffen, L.M. Weight gain among men and women who have a child enter their home. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abell, L.P.; A Tanase, K.; Gilmore, M.L.; E Winnicki, A.; Holmes, V.L.; Hartos, J. Do physical activity levels differ by number of children at home in women aged 25–44 in the general population? Women’s Health 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Candelaria, J.I.; Sallis, J.F.; Conway, T.L.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D.; Slymen, D.J. Differences in physical activity among adults in households with and without children. J. Phys. Act. Health 2012, 9, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, E.; Lahelma, E.; Virtanen, M.; Prättälä, R.; Pietinen, P. Gender, socioeconomic status and family status as determinants of food behaviour. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 46, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, H.H.; Hofer, T.P.; Davis, M.M. Adult fat intake associated with the presence of children in households: Findings from NHANES III. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2007, 20, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balan, S.; Widner, G.; Chen, H.-J.; Hudson, D.; Gehlert, S.; Price, R.K. Motherhood, psychological risks, and Resources in relation to alcohol use disorder: Are there differences between black and white women? ISRN Addict. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajema, K.-J.; Knibbe, R.A. Changes in social roles as predictors of changes in drinking behaviour. Addiction 1998, 93, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuntsche, S.; Knibbe, R.A.; Kuntsche, E.; Gmel, G. Housewife or working mum-each to her own? The relevance of societal factors in the association between social roles and alcohol use among mothers in 16 industrialized countries. Addiction 2011, 106, 1925–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oesterle, S.; Hawkins, J.D.; Hill, K.G. Men’s and women’s pathways to adulthood and associated substance misuse. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2011, 72, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paradis, C. Parenthood, drinking locations and heavy drinking. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldron, I.; Lye, D. Family roles and smoking. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1989, 5, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Lippe, E.; Rattay, P. Health-Risk Behaviour of Women and Men. Differences According to Partnership and Parenthood. Results of the German Health Update (GEDA) Survey 2009–2010. In A Demographic Perspective on Gender. Family and Health in Europe; Doblhammer, G., Gumà, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 233–261. [Google Scholar]

- Nomaguchi, K.M. Parenthood and psychological well-being: Clarifying the role of child age and parent-child relationship quality. Soc. Sci. Res. 2012, 41, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hank, K.; Wagner, M. Parenthood, Marital Status, and Well-Being in Later Life: Evidence from SHARE. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Ricca, E.G.; Pelloni, A. The Paradox of Children and Life Satisfaction. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 111, 725–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falci, C.; Mortimer, J.T.; Noel, H. Parental timing and depressive symptoms in early adulthood. Adv. Life Course Res. 2010, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahn, R.S.; Certain, L.; Whitaker, R.C. A Reexamination of Smoking Before, During, and After Pregnancy. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 1801–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avison, W.R.; Davies, L. Family structure, gender, and health in the context of the life course. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2005, 60, S113–S116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floderus, B.; Hagman, M.; Aronsson, G.; Marklund, S.; Wikman, A. Medically certified sickness absence with insurance benefits in women with and without children. Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 22, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rattay, P.; von der Lippe, E.; Borgmann, L.-S.; Lampert, T. Gesundheit von alleinerziehenden Müttern und Vätern in Deutschland [Health of single mothers and fathers in Germany]. JoHM 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M. Is being childless detrimental to a woman’s health and well-being across her life course? Women’s Health Issues 2015, 25, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, E.E. The effects of fatherhood on the health of men: A review of the literature. J. Men’s Health 2004, 1, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, C.; Bonas, S.; Spencer, N.; Dolan, A.; Coe, C.; Moy, R. Smoking behaviour change among fathers of new infants. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condon, J.T.; Corkindale, C.J.; Boyce, P. The First-Time Fathers Study: A prospective study of the mental health and wellbeing of men during the transition to parenthood. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2004, 38, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einiö, E.; Nisén, J.; Martikainen, P. Is young fatherhood causally related to midlife mortality? A sibling fixed-effect study in Finland. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 69, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eisenberg, M.L.; Park, Y.; Hollenbeck, A.R.; Lipshultz, L.I.; Schatzkin, A.; Pletcher, M.J. Fatherhood and the risk of cardiovascular mortality in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 3479–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, S.O. Family structure and fathers’ well-being: Trajectories of mental health and self-rated health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2009, 50, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntsche, S.; Kuendig, H.; Bloomfield, K.; Gmel, G.; Knibbe, R.A.; Kramer, S.; Grittner, U. Gender and cultural differences in the association between family roles, social stratification, and alcohol use: A European cross-cultural analysis. Alcohol Alcohol 2006, 41, i37–i46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kuntsche, S.; Knibbe, R.A.; Gmel, G. Parents’ alcohol use: Gender differences in the impact of household and family chores. Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 22, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastekaasa, A. Parenthood, gender and sickness absence. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 50, 1827–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomaguchi, K.M.; Bianchi, S.M. Exercise Time: Gender Differences in the Effects of Marriage, Parenthood, and Employment. J. Marriage Fam. 2004, 66, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, K.; Pace, G.T. Gender differences in depression across parental roles. Soc. Work 2015, 60, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huijts, T.; Kraaykamp, G.; Subramanian, S.V. Childlessness and Psychological Well-Being in Context: A Multilevel Study on 24 European Countries. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2013, 29, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burström, B.; Whitehead, M.; Clayton, S.; Fritzell, S.; Vannoni, F.; Costa, G. Health inequalities between lone and couple mothers and policy under different welfare regimes—The example of Italy, Sweden and Britain. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hansen, T.; Slagsvold, B.; Moum, T. Childlessness and psychological well-being in midlife and old age: An examination of parental status effects across a range of outcomes. Soc. Indic. Res. 2009, 94, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendig, H.; Dykstra, P.A.; Van Gaalen, R.I.; Melkas, T. Health of aging parents and childless individuals. J. Fam. Issues 2007, 28, 1457–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanaka, K.; Johnson, N.E. Childlessness and mental well-being in a global context. J. Fam. Issues 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, J.; Simon, R.W.; Andersson, M.A. Parenthood and happiness: Effects of work-family reconciliation policies in 22 OECD countries. AJS 2016, 122, 886–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hansen, T. Parenthood and Happiness: A Review of Folk Theories Versus Empirical Evidence. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 108, 29–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nelson-Coffey, S.K.; Kushlev, K.; Lyubomirsky, S. The pains and pleasures of parenting: When, why, and how is parenthood associated with more or less well-being? Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 846–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachs-Ericsson, N.; Ciarlo, J.A. Gender, Social Roles, and Mental Health: An Epidemiological Perspective. Sex. Roles 2000, 43, 605–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techniker, K. (Ed.) Gesundheitsreport 2016. Gesundheit Zwischen Beruf und Familie [Health Report 2016. Health between Work and Family]; Techniker Krankenkasse: Hamburg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, R.; Myrskylä, M. A global perspective on happiness and fertility. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2011, 37, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlücker, F.U.; Blumenfelder, A.R. Effects of age at first birth on health of mothers aged 45 to 56. J. Fam. Stud. 2014, 26, 347–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henretta, J.C.; Grundy, E.M.; Okell, L.C.; Wadsworth, M.E. Early motherhood and mental health in midlife: A study of British and American cohorts. Aging Ment. Health 2008, 12, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, D.H.; Kogan, L.; Manor, O.; Gielchinsky, Y.; Dior, U.; Laufer, N. Influence of late-age births on maternal longevity. Ann. Epidemiol. 2015, 25, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrskylä, M.; Margolis, R. Happiness: Before and after the kids. Demography 2014, 51, 1843–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sabbath, E.L.; Mejía-Guevara, I.; Noelke, C.; Berkman, L.F. The long-term mortality impact of combined job strain and family circumstances: A life course analysis of working American mothers. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 146, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carlson, D.L. Explaining the curvilinear relationship between age at first birth and depression among women. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umberson, D.; Liu, H.; Mirowsky, J.; Reczek, C. Parenthood and trajectories of change in body weight over the life course. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Becchetti, L.; Ricca, E.G.; Pelloni, A. Children, Happiness and Taxation; SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research No. 230; German Institute for Economic Research (DIW): Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, C.; Jentsch, F.; Allen, J.; Hoebel, J.; Kratz, A.L.; von der Lippe, E.; Müters, S.; Schmich, P.; Thelen, J.; Wetzstein, M.; et al. Data resource profile: German Health Update (GEDA)—The health interview survey for adults in Germany. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gabler, S.; Häder, S. Generierung von Telefonstichproben mit TelSuSa [Generating telephone samples using TelSuSa]. Zuma-Nachr. 1999, 44, 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lampert, T.; Kroll, L.; Müters, S.; Stolzenberg, H. Messung des sozioökonomischen Status in der Studie „Gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell “(GEDA) [Measurement of socio-economic status in the „German Health Update“ (GEDA)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2013, 56, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jann, B. Predictive Margins and Marginal Effects in Stata. In Proceedings of the 11th German Stata Users Group Meeting, Potsdam, Germany, 7 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppanner, L.; Perales, F.; Baxter, J. Harried and Unhealthy? Parenthood, Time Pressure, and Mental Health. J. Marriage Fam. 2019, 81, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, J.M.; Fergusson, D.M.; Horwood, L.J. Early motherhood and subsequent life outcomes. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, I.; Chen, M.; Kneale, D.; Jager, J. Becoming adults in Britain: Lifestyles and wellbeing in times of social change. Longitud. Life Course Stud. 2012, 3, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grundy, E.; Foverskov, E. Age at First Birth and Later Life Health in Western and Eastern Europe. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2016, 42, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raymo, J.M.; Carlson, M.; VanOrman, A.; Lim, S.; Perelli-Harris, B.; Iwasawa, M. Educational differences in early childbearing: A cross-national comparative study. Demogr. Res. 2015, 33, 65–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, C.; Ryff, C.D. Early parenthood as a link between childhood disadvantage and adult heart problems: A gender-based approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 171, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pollmann-Schult, M. Parenthood and life satisfaction in Germany. CPoS 2013, 38, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrskylä, M.; Margolis, R. Parental Benefits Improve Parental Well-Being: Evidence from a 2007 Policy Change in Germany; MPIDR Working Paper WP-2013-010; Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research: Rostock, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, K.J.; Keenan, K.; Grundy, E.M.; Kolk, M.; Myrskylä, M. Reproductive history and post-reproductive mortality: A sibling comparison analysis using Swedish register data. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 155, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Statistisches Bundesamt [Federal Statistical Office] (Ed.) Geburtentrends und Familiensituation in Deutschland 2012 [Birth Trends and Family Situation in Germany 2012]; Statistisches Bundesamt [Federal Statistical Office]: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Koropeckyj-Cox, T. Beyond parental status: Psychological well-being in middle and old age. J. Marriage Fam. 2002, 64, 957–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R.W.; Caputo, J. The Costs and Benefits of Parenthood for Mental and Physical Health in the United States: The Importance of Parenting Stage. Soc. Ment. Health 2019, 9, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hank, K. Childbearing history, later-life health, and mortality in Germany. Popul. Stud. 2010, 64, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullinger, L.R. The Effect of Paid Family Leave on Infant and Parental Health in the United States. J. Health Econ. 2019, 66, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.C.; Modrek, S.; White, J.S.; Batra, A.; Collin, D.F.; Hamad, R. The effect of California’s paid family leave policy on parent health: A quasi-experimental study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 251, 112915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Jahagirdar, D.; Dimitris, M.C.; Labrecque, J.A.; Strumpf, E.C.; Kaufman, J.S.; Vincent, I.; Atabay, E.; Harper, S.; Earle, A.; et al. The Impact of Parental and Medical Leave Policies on Socioeconomic and Health Outcomes in OECD Countries: A Systematic Review of the Empirical Literature. Milbank Q 2018, 96, 434–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, Z.; Garrett, C.C.; Hewitt, B.; Keogh, L.; Hocking, J.; Kavanagh, A.M. The maternal health outcomes of paid maternity leave: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 130, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Women | Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n Unweighted | % Weighted | Missing % Unweighted | n Unweighted | % Weighted | Missing % Unweighted | |

| Total | 21,379 | 100.0 | 0 | 17,717 | 100.0 | 0 |

| Outcome variables | ||||||

| Poor self-rated general health | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||||

| Yes | 3921 | 19.9 | 2663 | 17.5 | ||

| No | 17,442 | 80.1 | 15,044 | 82.5 | ||

| Depression | 0.3 | 0.1 | ||||

| Yes | 1931 | 8.6 | 889 | 5.2 | ||

| No | 19,382 | 91.4 | 16,804 | 94.8 | ||

| Back pain | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||||

| Yes | 3868 | 18.9 | 2115 | 13.3 | ||

| No | 17,484 | 81.1 | 15,580 | 86.7 | ||

| Overweight | 2.8 | 1.0 | ||||

| Yes | 6875 | 35.0 | 9054 | 53.7 | ||

| No | 13,898 | 65.0 | 8,486 | 46.3 | ||

| Smoking | <0.1 | <0.1 | ||||

| Yes | 6780 | 33.4 | 6613 | 40.0 | ||

| No | 14,590 | 66.6 | 11,100 | 60.0 | ||

| Sporting inactivity | 0.1 | <0.1 | ||||

| Yes | 5490 | 29.2 | 4451 | 29.0 | ||

| No | 15,878 | 70.8 | 13,260 | 71.0 | ||

| Predictor and control variables | ||||||

| Age groups | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 18–24 years | 3221 | 15.9 | 3262 | 16.2 | ||

| 25–34 years | 4408 | 24.1 | 3650 | 24.0 | ||

| 35–44 years | 6771 | 27.1 | 5187 | 27.0 | ||

| 45–54 years | 6979 | 33.0 | 5618 | 32.8 | ||

| Parental status | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Child(ren) in household | 9731 | 55.3 | 6082 | 37.0 | ||

| No child in household | 11,648 | 44.7 | 11,635 | 63.0 | ||

| Pre-school child in household (0–6 years) | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Yes | 4109 | 19.2 | 2688 | 15.2 | ||

| No | 17,270 | 80.8 | 15,029 | 84.8 | ||

| Partner status | 0.4 | 0.6 | ||||

| Partner | 13,022 | 67.6 | 10,097 | 63.7 | ||

| No partner | 8266 | 32.3 | 7521 | 36.3 | ||

| Socioeconomic status | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||||

| High | 6492 | 16.0 | 6120 | 17.0 | ||

| Middle | 12,608 | 61.6 | 9680 | 59.2 | ||

| Low | 2236 | 22.4 | 1889 | 23.8 | ||

| Employment status | 0.5 | 0.4 | ||||

| Full-time employed | 7919 | 34.2 | 13,581 | 76.4 | ||

| Part-time employed | 8496 | 39.8 | 1692 | 9.1 | ||

| Not employed | 4867 | 26.0 | 2379 | 14.5 | ||

| Residential region | 0 | 0 | ||||

| West Germany | 17,195 | 80.5 | 14,216 | 79.9 | ||

| East Germany | 4184 | 19.5 | 3501 | 20.1 | ||

| Survey year | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 2009 | 7909 | 37.5 | 6058 | 34.2 | ||

| 2010 | 8186 | 38.5 | 6269 | 34.6 | ||

| 2012 | 5284 | 24.0 | 5390 | 31.2 | ||

| Women | Child in Household | Total | 18–24 Years | 25–34 Years | 35–44 Years | 45–54 Years | ||||||||||

| % | 95% CI | p | % | 95% CI | p | % | 95% CI | p | % | 95% CI | p | % | 95% CI | p | ||

| Poor general health | No | 21.3 | 20.4–22.2 | *** | 11.6 | 10.5–12.9 | 13.5 | 11.8–15.3 | * | 21.6 | 19.3–24.1 | ** | 31.4 | 29.7–33.1 | *** | |

| Yes | 18.1 | 17.1–19.1 | 13.1 | 8.8–19.2 | 16.5 | 14.7–18.5 | 17.7 | 16.4–19.1 | 21.1 | 19.1–23.4 | ||||||

| Depression | No | 9.7 | 9.1–10.4 | *** | 4.3 | 3.6–5.2 | * | 8.9 | 7.6–10.3 | 11.7 | 9.9–13.6 | *** | 13.1 | 12.0–14.3 | *** | |

| Yes | 7.2 | 6.6–7.9 | 7.7 | 4.4–13.0 | 7.1 | 5.9–8.4 | 7.1 | 6.3–8.0 | 7.6 | 6.4-9.0 | ||||||

| Back pain | No | 19.1 | 18.3–20.0 | 12.6 | 11.4–13.9 | *** | 13.9 | 12.2–15.7 | *** | 19.4 | 17.2–21.9 | 25.9 | 24.3–27.5 | *** | ||

| Yes | 18.6 | 17.7–19.6 | 27.1 | 20.5–34.8 | 18.7 | 16.8–20.6 | 18.1 | 16.8–19.4 | 19.2 | 17.2–21.3 | ||||||

| Overweight | No | 33.4 | 32.4–34.5 | *** | 15.7 | 14.3–17.2 | *** | 26.7 | 24.5–29.0 | *** | 35.9 | 33.1–38.8 | 47.6 | 45.8–49.4 | *** | |

| Yes | 36.8 | 35.7–38.0 | 32.3 | 25.1–40.4 | 37.0 | 34.6–39.4 | 36.3 | 34.7–38.0 | 38.0 | 35.5–40.5 | ||||||

| Smoking | No | 36.6 | 34.6–36.7 | *** | 32.8 | 31.0–34.6 | *** | 35.6 | 33.2–38.0 | 39.1 | 36.3–42.0 | *** | 36.5 | 34.8–38.2 | *** | |

| Yes | 30.6 | 29.5–31.8 | 49.0 | 40.9–57.1 | 33.7 | 31.4–36.1 | 30.7 | 29.2–32.3 | 25.1 | 23.0–27.4 | ||||||

| Sporting inactivity | No | 25.9 | 24.9–26.9 | *** | 14.4 | 13.1–15.9 | *** | 21.2 | 19.1–23.4 | *** | 31.1 | 28.4–34.0 | 34.2 | 32.5–35.9 | *** | |

| Yes | 33.4 | 32.2–34.6 | 38.0 | 30.4–46.2 | 39.9 | 37.5–42.3 | 32.6 | 31.0–34.3 | 26.0 | 23.7–28.4 | ||||||

| Men | Child in Household | Total | 18–24 Years | 25–34 Years | 35–44 Years | 45–54 Years | ||||||||||

| % | 95% CI | p | % | 95% CI | p | % | 95% CI | p | % | 95% CI | p | % | 95% CI | p | ||

| Poor general health | No | 17.7 | 16.8–18.6 | 7.9 | 6.9–9.0 | 10.9 | 9.4–12.5 | * | 20.8 | 18.4–23.3 | ** | 29.7 | 27.8–31.7 | *** | ||

| Yes | 17.1 | 15.9–18.4 | 8.8 | 3.0–22.8 | 14.1 | 11.3–17.4 | 15.8 | 14.2–17.7 | 20.6 | 18.3–23.0 | ||||||

| Depression | No | 5.5 | 5.0–6.0 | 2.2 | 1.7–2.8 | 4.7 | 3.8–5.8 | ** | 7.6 | 6.2–9.2 | *** | 7.8 | 6.7–8.9 | |||

| Yes | 4.6 | 3.9–5.4 | 3.9 | 0.8–17.0 | 1.8 | 1.0–3.1 | 4.3 | 3.4–5.3 | 6.8 | 5.3–8.6 | ||||||

| Back pain | No | 12.7 | 11.9–13.5 | * | 6.6 | 5.7–7.6 | * | 9.6 | 8.2–11.2 | 14.6 | 12.6–16.8 | 19.1 | 17.5–20.9 | * | ||

| Yes | 14.3 | 13.2–15.4 | 16.4 | 7.7–31.7 | 11.3 | 9.2–13.8 | 14.2 | 12.8–15.9 | 15.9 | 13.9–18.1 | ||||||

| Overweight | No | 48.8 | 47.6–50.0 | *** | 25.0 | 23.3–26.7 | 42.0 | 39.7–44.3 | *** | 58.5 | 55.9–61.2 | * | 68.3 | 66.4–70.2 | ||

| Yes | 62.2 | 60.7–63.6 | 29.7 | 17.5–45.6 | 54.8 | 50.9–58.7 | 62.8 | 60.7–64.8 | 65.9 | 63.4–68.3 | ||||||

| Smoking | No | 41.4 | 40.3–42.6 | *** | 37.3 | 35.5–39.1 | *** | 44.8 | 42.5–47.2 | 45.6 | 42.9–48.4 | *** | 39.8 | 37.8–41.9 | *** | |

| Yes | 37.5 | 36.0–39.1 | 70.5 | 54.8–82.4 | 47.5 | 43.6–51.4 | 36.8 | 34.7–39.0 | 32.4 | 29.9–35.1 | ||||||

| Sporting inactivity | No | 27.3 | 26.2–28.3 | *** | 11.1 | 9.9–12.4 | *** | 22.0 | 20.1–24.1 | *** | 34.8 | 32.2–37.6 | 40.7 | 38.7–42.8 | *** | |

| Yes | 32.0 | 30.5–33.5 | 39.4 | 25.2–55.6 | 33.4 | 29.8–37.2 | 33.1 | 31.0–35.3 | 29.6 | 27.1–32.2 | ||||||

| Women | Poor Self-Rated General Health | Depression | Back Pain | Overweight | Smoking | Sporting Inactivity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p | OR | p | OR | p | OR | p | OR | p | OR | p | |

| Parental status: Child in household | ||||||||||||

| No child | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Child | 2.43 | <0.001 | 3.92 | <0.001 | 2.19 | <0.001 | 2.75 | <0.001 | 6.15 | <0.001 | 3.39 | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.06 | <0.001 | 1.16 | <0.001 | 1.04 | <0.001 | 1.10 | <0.001 | 1.08 | <0.001 | 1.13 | <0.001 |

| Age#Age | 0.997 | <0.001 | 0.999 | <0.001 | 0.998 | <0.001 | 0.998 | <0.001 | ||||

| Child#Age | ||||||||||||

| No child#Age | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Child#Age | 0.96 | <0.001 | 0.87 | <0.001 | 0.96 | <0.001 | 0.92 | <0.001 | 0.88 | <0.001 | 0.91 | <0.001 |

| Child#Age#Age | ||||||||||||

| No child#Age#Age | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||||

| Child#Age#Age | 1.002 | 0.005 | 1.001 | 0.013 | 1.002 | <0.001 | 1.001 | 0.016 | ||||

| Pre-school child in household | ||||||||||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 0.61 | <0.001 | 0.68 | 0.004 | 0.91 | 0.265 | 1.02 | 0.770 | 0.55 | <0.001 | 1.42 | <0.001 |

| Partner status | ||||||||||||

| Partner | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| No partner | 1.15 | 0.007 | 1.85 | <0.001 | 1.13 | 0.023 | 0.79 | <0.001 | 1.45 | <0.001 | 0.92 | 0.076 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||||||||

| High | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Middle | 1.78 | <0.001 | 1.21 | 0.007 | 1.55 | <0.001 | 1.75 | <0.001 | 1.65 | <0.001 | 2.13 | <0.001 |

| Low | 2.92 | <0.001 | 1.39 | 0.002 | 2.17 | <0.001 | 2.51 | <0.001 | 2.68 | <0.001 | 4.56 | <0.001 |

| Employment status | ||||||||||||

| Full-time | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Part-time | 1.06 | 0.278 | 1.49 | <0.001 | 0.97 | 0.590 | 0.87 | 0.002 | 0.83 | <0.001 | 0.78 | <0.001 |

| Not employed | 2.07 | <0.001 | 2.66 | <0.001 | 1.35 | <0.001 | 1.05 | 0.404 | 0.78 | <0.001 | 1.10 | 0.071 |

| Residential region | ||||||||||||

| West Germany | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| East Germany | 0.99 | 0.868 | 0.97 | 0.706 | 1.04 | 0.465 | 1.06 | 0.208 | 1.01 | 0.836 | 1.10 | 0.053 |

| Men | Poor Self-Rated General Health | Depression | Back Pain | Overweight | Smoking | Sporting Inactivity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p | OR | p | OR | p | OR | p | OR | p | OR | p | |

| Parental status: Child in household | ||||||||||||

| No child | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Child | 1.53 | 0.022 | 0.70 | 0.267 | 1.13 | 0.520 | 1.27 | 0.055 | 3.98 | <0.001 | 4.15 | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.12 | <0.001 | 1.19 | <0.001 | 1.09 | <0.001 | 1.11 | <0.001 | 1.09 | <0.001 | 1.17 | <0.001 |

| Age#Age | 0.999 | 0.007 | 0.997 | <0.001 | 0.999 | 0.005 | 0.999 | <0.001 | 0.998 | <0.001 | 0.997 | <0.001 |

| Child#Age | ||||||||||||

| No child#Age | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||||||

| Child#Age | 0.886 | <0.001 | 0.898 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Child#Age#Age | ||||||||||||

| No child#Age#Age | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Child#Age#Age | 0.999 | <0.001 | 1.001 | 0.175 | 0.9997 | 0.164 | 0.9996 | 0.006 | 1.002 | 0.002 | 1.002 | 0.038 |

| Pre-school child in household | ||||||||||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 0.75 | 0.010 | 0.59 | 0.007 | 0.90 | 0.356 | 0.93 | 0.332 | 0.81 | 0.015 | 1.04 | 0.651 |

| Partner status | ||||||||||||

| Partner | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| No partner | 1.14 | 0.076 | 1.57 | <0.001 | 0.84 | 0.028 | 0.82 | <0.001 | 1.20 | 0.001 | 1.17 | 0.009 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||||||||

| High | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Middle | 2.48 | <0.001 | 1.57 | <0.001 | 1.77 | <0.001 | 1.46 | <0.001 | 1.77 | <0.001 | 2.53 | <0.001 |

| Low | 3.93 | <0.001 | 2.04 | <0.001 | 2.43 | <0.001 | 2.00 | <0.001 | 2.55 | <0.001 | 4.53 | <0.001 |

| Employment status | ||||||||||||

| Full-time | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Part-time | 1.61 | <0.001 | 2.27 | <0.001 | 1.28 | 0.024 | 0.68 | <0.001 | 0.93 | 0.326 | 0.90 | 0.230 |

| Not employed | 3.47 | <0.001 | 3.99 | <0.001 | 2.04 | <0.001 | 0.78 | <0.001 | 0.87 | 0.035 | 0.98 | 0.744 |

| Residential region | ||||||||||||

| West Germany | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| East Germany | 0.88 | 0.048 | 0.75 | 0.009 | 0.90 | 0.134 | 0.92 | 0.083 | 1.11 | 0.034 | 1.16 | 0.007 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rattay, P.; von der Lippe, E. Association between Living with Children and the Health and Health Behavior of Women and Men. Are There Differences by Age? Results of the “German Health Update” (GEDA) Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093180

Rattay P, von der Lippe E. Association between Living with Children and the Health and Health Behavior of Women and Men. Are There Differences by Age? Results of the “German Health Update” (GEDA) Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(9):3180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093180

Chicago/Turabian StyleRattay, Petra, and Elena von der Lippe. 2020. "Association between Living with Children and the Health and Health Behavior of Women and Men. Are There Differences by Age? Results of the “German Health Update” (GEDA) Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 9: 3180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093180

APA StyleRattay, P., & von der Lippe, E. (2020). Association between Living with Children and the Health and Health Behavior of Women and Men. Are There Differences by Age? Results of the “German Health Update” (GEDA) Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093180