The Characteristics of Patients Frequently Tested and Repeatedly Infected with Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

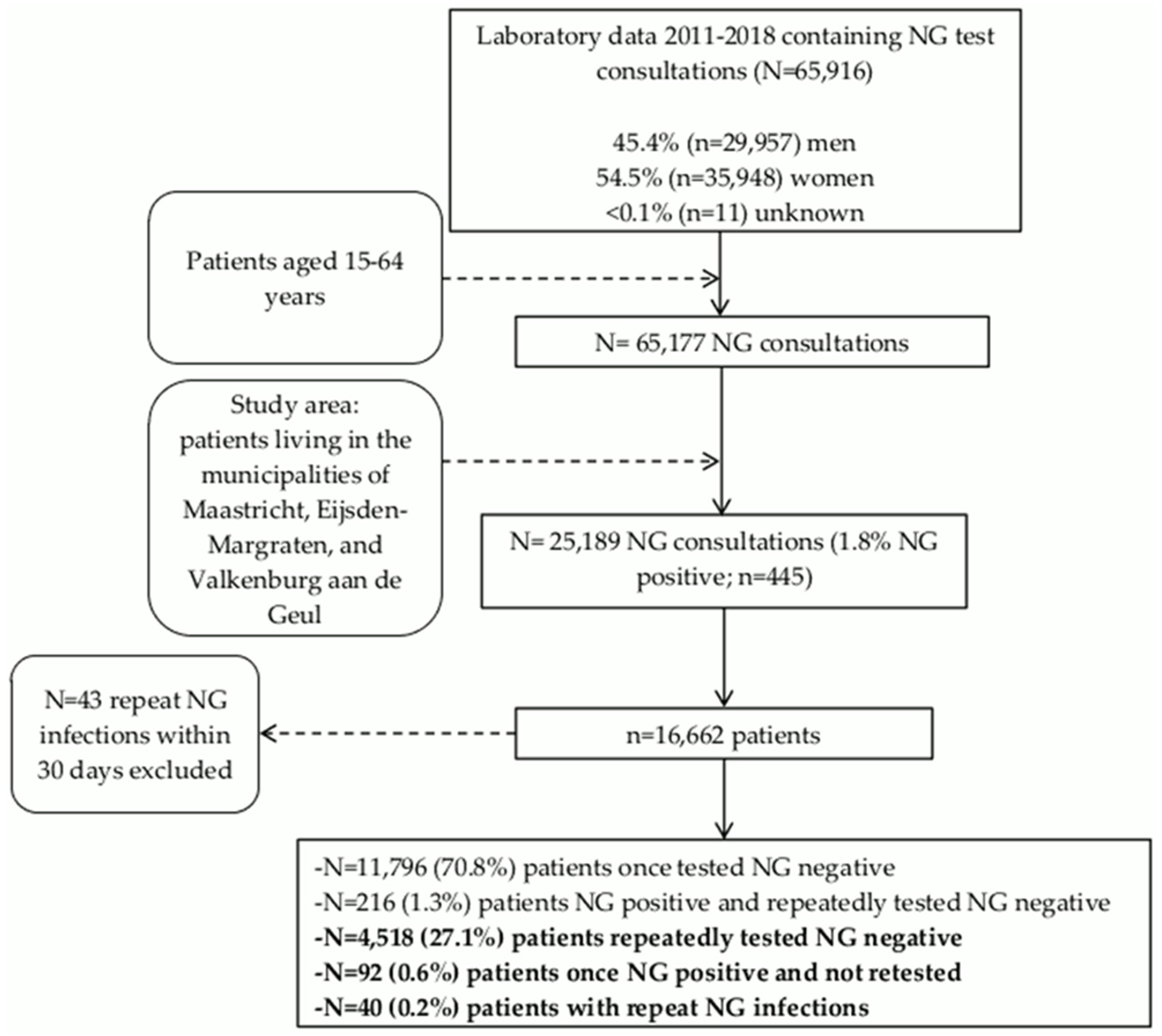

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Outcome Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.4. Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. NG Testing and Positivity in the Residential Population

3.2. Characteristics of Patients with Repeat NG Infections

3.3. Characteristics of Patients Once Tested NG Positive and Not Retested

3.4. Geographical Mapping

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Newman, L.; Rowley, J.; Vander Hoorn, S.; Wijesooriya, N.S.; Unemo, M.; Low, N.; Stevens, G.; Gottlieb, S.; Kiarie, J.; Temmerman, M. Global Estimates of the Prevalence and Incidence of Four Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections in 2012 Based on Systematic Review and Global Reporting. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bignell, C.; Unemo, M.; European, S.T.I.G.E.B. 2012 European guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of gonorrhoea in adults. Int. J. STD AIDS 2013, 24, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaro, N. Sexually Transmitted Infections in Primary Care 2013 (RCGP/BASHH). Available online: www.rcgp.org and www.bashh.org/guidelines (accessed on 14 October 2019).

- Workowski, K.A. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61 (Suppl. 8), S759–S762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosenfeld, C.B.; Workowski, K.A.; Berman, S.; Zaidi, A.; Dyson, J.; Mosure, D.; Bolan, G.; Bauer, H.M. Repeat infection with Chlamydia and gonorrhea among females: A systematic review of the literature. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2009, 36, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, M.; Scott, K.C.; Kent, C.K.; Klausner, J.D. Chlamydial and gonococcal reinfection among men: A systematic review of data to evaluate the need for retesting. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2007, 83, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijers, J.; van Liere, G.; Hoebe, C.; Cals, J.W.L.; Wolffs, P.F.G.; Dukers-Muijrers, N. Test of cure, retesting and extragenital testing practices for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae among general practitioners in different socioeconomic status areas: A retrospective cohort study, 2011–2016. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, K.K.; Molotnikov, L.E.; Roosevelt, K.A.; Elder, H.R.; Klevens, R.M.; DeMaria, A., Jr.; Aral, S.O. Characteristics of Cases With Repeated Sexually Transmitted Infections, Massachusetts, 2014–2016. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gesink, D.C.; Sullivan, A.B.; Miller, W.C.; Bernstein, K.T. Sexually transmitted disease core theory: Roles of person, place, and time. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 174, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotz, H.M.; van Oeffelen, L.A.; Hoebe, C.; van Benthem, B.H. Regional differences in chlamydia and gonorrhoeae positivity rate among heterosexual STI clinic visitors in the Netherlands: Contribution of client and regional characteristics as assessed by cross-sectional surveillance data. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e022793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, S.B.; Garrett, S.M.; Stanley, J.; Pullon, S.R.H. Retesting and repeat positivity following diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoea in New Zealand: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Netherlands. Available online: https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb] (accessed on 22 October 2019).

- QGIS Development Team 2019. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. Available online: https://qgis.org (accessed on 4 November 2019).

- Slurink, I.; van Aar, F.; Op de Coul, E.; Heijne, J.; van Wees, D.; Hoenderboom, B.; Visser, M.; den Daas, C.; Woestenberg, P.; Gotz, H.; et al. Sexually transmitted infections in the Netherlands in 2018; Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelisse, V.J.; Zhang, L.; Law, M.; Chen, M.Y.; Bradshaw, C.S.; Bellhouse, C.; Fairley, C.K.; Chow, E.P.F. Concordance of gonorrhoea of the rectum, pharynx and urethra in same-sex male partnerships attending a sexual health service in Melbourne, Australia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priest, D.; Ong, J.J.; Chow, E.P.F.; Tabrizi, S.; Phillips, S.; Bissessor, M.; Fairley, C.K.; Bradshaw, C.S.; Read, T.R.H.; Garland, S.; et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae DNA bacterial load in men with symptomatic and asymptomatic gonococcal urethritis. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2017, 93, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissessor, M.; Tabrizi, S.N.; Fairley, C.K.; Danielewski, J.; Whitton, B.; Bird, S.; Garland, S.; Chen, M.Y. Differing Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacterial loads in the pharynx and rectum in men who have sex with men: Implications for gonococcal detection, transmission, and control. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 4304–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All Individuals Tested for NG | Frequently Tested NG Negative | Repeat NG Infections | Once NG Positive and not Retested | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | OR (95%CI) | Adj. OR (95%CI) | % (n) | OR (95%CI) | Adj. OR (95%CI) | ||

| Overall % (n) | 100 (16,662) | 100 (4,518) | 100 (40) | 100 (92) | ||||

| Initial test location | ||||||||

| Mental healthcare | 0.7 (121) | 0.6 (28) | 2.5 (1) | 8.55 (1.02−71.79) | 8.47 (0.91−78.59) | 1.1 (1) | 1.22 (0.16−9.16) | 0.53 (0.07−4.20) |

| STI clinic | 48.1 (8022) | 53.6 (2,422) | 75.0 (30) | 2.96 (1.30−6.76) | 3.29 (1.36−8.00) | 40.2 (37) | 0.52 (0.34−0.80) | 0.51 (0.33−0.79) |

| Hospital | 13.3 (2216) | 8.7 (393) | 5.0 (2) | 1.22 (0.25−5.88) | 0.33 (0.06−1.88) | 5.4 (5) | 0.44 (0.17−1.10) | 0.31 (0.11−0.85) |

| General practitioner | 37.8 (6303) | 37.1 (1675) | 17.5 (7) | 1 | 1 | 53.3 (49) | 1 | 1 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Men | 37.1 (6182) | 33.8 (1529) | 87.5 (35) | 13.68 (5.35−35.00) | 8.38 (3.11−22.55) | 72.8 (67) | 5.24 (3.30−8.33) | 7.09 (4.33−11.62) |

| Women | 62.9 (10,480) | 66.2 (2989) | 12.5 (5) | 1 | 1 | 27.2 (92) | 1 | 1 |

| Age | ||||||||

| <25 years | 46.5 (7748) | 44.9 (2028) | 22.5 (9) | 1 | 1 | 45.7 (42) | 1 | |

| ≥25 years | 53.5 (8914) | 55.1 (2490) | 77.5 (31) | 2.81 (1.33−5.91) | 3.10 (1.33−7.23) | 54.3 (50) | 0.97 (0.64−1.47) | |

| Urbanization | ||||||||

| Rural | 31.1 (5182) | 29.6 (1337) | 47.5 (19) | 2.15 (1.15−4.01) | 1.93 (0.97−3.82) | 37.0 (34) | 1.39 (0.91−2.14) | |

| Urban | 68.9 (11474) | 70.4 (4516) | 52.5 (21) | 1 | 1 | 63.0 (58) | 1 | |

| HIV co-infection | ||||||||

| Not tested | 42.1 (7014) | 25.4 (1149) | 20.0 (8) | 1.15 (0.50−2.62) | 2.75 (1.13−6.70) | 41.3 (38) | 2.27 (1.48−3.50) | 3.99 (2.52−6.32) |

| Yes | 1.5 (243) | 1.5 (70) | 50.0 (20) | 28.28 (13.31−60.09) | 23.89 (9.19−62.11) | 6.5 (6) | 5.89 (2.44−14.22) | 5.38 (2.04−14.16) |

| No | 56.4 (9405) | 73.0 (3299) | 30.0 (12) | 1 | 1 | 52.2 (48) | 1 | 1 |

| Any CT co-infectiona | ||||||||

| Yes | 12.5 (2076) | 25.5 (1151) | 65.0 (26) | 5.43 (2.83−10.44) | 4.91 (2.43−9.96) | 29.3 (27) | 1.22 (0.77−1.91) | |

| No | 87.4 (14,558) | 74.5 (3367) | 35.0 (14) | 1 | 1 | 70.7 (65) | 1 | |

| All Individuals Tested for NG | Frequently Tested NG Negative | Repeat NG Infections | Once NG Positive and not repeatedly tested | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | OR (95%CI) | Adj. OR (95%CI) | % (n) | OR (95%CI) | Adj. OR (95%CI) | |

| Overall % (n) | 100 (8022) | 100 (2422) | 100 (30) | 100 (37) | ||||

| Maximum number of sex partners | ||||||||

| Unknown | 2.8 (228) | 1.4 (34) | 3.3 (1) | 8.50 (0.52−139.01) | na | 2.7 (1) | 1.21 (0.15−10.17) | |

| 0−1 | 25.8 (2068) | 11.9 (289) | 3.3 (1) | 1 | 1 | 18.9 (7) | 1 | |

| 2−3 | 42.6 (3420) | 44.1 (1068) | 20.0 (6) | 1.62 (0.20−13.54) | 0.64 (0.07−5.82) | 29.7 (11) | 0.43 (0.16−1.11) | |

| ≥4 | 28.7 (2306) | 42.6 (1031) | 73.3 (22) | 6.17 (0.83−45.95) | 1.08 (0.13−9.04) | 48.6 (18) | 0.72 (0.30−1.74) | |

| Any urogenital symptoms | ||||||||

| Unknown | 4.6 (371) | 2.3 (55) | 3.3 (1) | 4.45 (0.46−43.48) | 3.23 (0.04−265.73) | 10.8 (4) | 4.85 (1.50−15.74) | 19.22 (4.29−86.05) |

| Yes | 54.0 (4329) | 67.4 (1633) | 86.7 (26) | 3.90 (1.18−12.91) | 8.31 (2.40−28.85) | 59.5 (22) | 0.90 (0.43−1.86) | 2.19 (0.99−4.80) |

| No | 41.4 (3322) | 30.3 (734) | 10.0 (3) | 1 | 1 | 29.7 (11) | 1 | 1 |

| Any Proctitis | ||||||||

| Unknown | 4.6 (371) | 2.3 (55) | 3.3 (1) | 2.70 (0.35−20.93) | 3.23 (0.04−265.73) | 10.8 (4) | 5.41 (1.83−15.95) | 19.22 (4.29−86.05) |

| Yes | 8.5 (680) | 11.8 (285) | 50.0 (15) | 7.83 (3.74−16.39) | 3.01 (1.32−6.85) | 13.5 (5) | 1.31 (0.50−3.41) | 0.93 (0.34−2.55) |

| No | 86.9 (6971) | 86.0 (2082) | 46.7 (14) | 1 | 1 | 75.7 (28) | 1 | 1 |

| Any oropharyngeal symptoms | ||||||||

| Unknown | 4.6 (371) | 2.3 (55) | 3.3 (1) | 1.80 (0.24−13.66) | 10.8 (4) | 4.65 (1.59−13.62) | 19.22 (4.29−86.05) | |

| Yes | 10.4 (831) | 15.9 (386) | 30.0 (9) | 2.31 (1.04−5.11) | 5.4 (2) | 0.33 (0.08−1.39) | 0.24 (0.06−1.04) | |

| No | 85.0 (6820) | 81.8 (1981) | 66.7 (20) | 1 | 83.8 (31) | 1 | 1 | |

| Any notification for STI | ||||||||

| Unknown | 3.5 (278) | 2.2 (54) | 3.3 (1) | 2.71 (0.35−21.05) | na | 2.7 (1) | 1.68 (0.22−12.68) | 0.45 (0.04−4.92) |

| Yes | 14.0 (1127) | 19.4 (469) | 53.3 (16) | 4.98 (2.38−10.43) | 3.19 (1.43−7.14) | 40.5 (15) | 2.89 (1.48−5.65) | 2.21 (1.10−4.44) |

| No | 82.5 (6617) | 78.4 (1899) | 43.3 (13) | 1 | 1 | 56.8 (21) | 1 | 1 |

| Transmission group | ||||||||

| MSW | 30.1 (2416) | 21.6 (523) | 6.7 (2) | 1.95 (0.32−11.68) | 2.05 (0.33−12.76) | 29.7 (11) | 4.59 (1.77−11.90) | 5.14 (1.94−13.62) |

| MSM | 11.2 (902) | 15.4 (372) | 83.3 (25) | 34.21 (10.27−113.90) | 41.16 (10.58−160.23) | 51.4 (19) | 11.14 (4.65−26.70) | 15.22 (5.91−39.18) |

| Women | 58.6 (4704) | 63.0 (1527) | 10.0 (3) | 1 | 1 | 18.9 (7) | 1 | 1 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wijers, J.; Hoebe, C.; Dukers-Muijrers, N.; Wolffs, P.; van Liere, G. The Characteristics of Patients Frequently Tested and Repeatedly Infected with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051495

Wijers J, Hoebe C, Dukers-Muijrers N, Wolffs P, van Liere G. The Characteristics of Patients Frequently Tested and Repeatedly Infected with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(5):1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051495

Chicago/Turabian StyleWijers, Juliën, Christian Hoebe, Nicole Dukers-Muijrers, Petra Wolffs, and Geneviève van Liere. 2020. "The Characteristics of Patients Frequently Tested and Repeatedly Infected with Neisseria gonorrhoeae" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 5: 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051495

APA StyleWijers, J., Hoebe, C., Dukers-Muijrers, N., Wolffs, P., & van Liere, G. (2020). The Characteristics of Patients Frequently Tested and Repeatedly Infected with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051495