Advanced Technology Use by Care Professionals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Acceptance Theories and Models

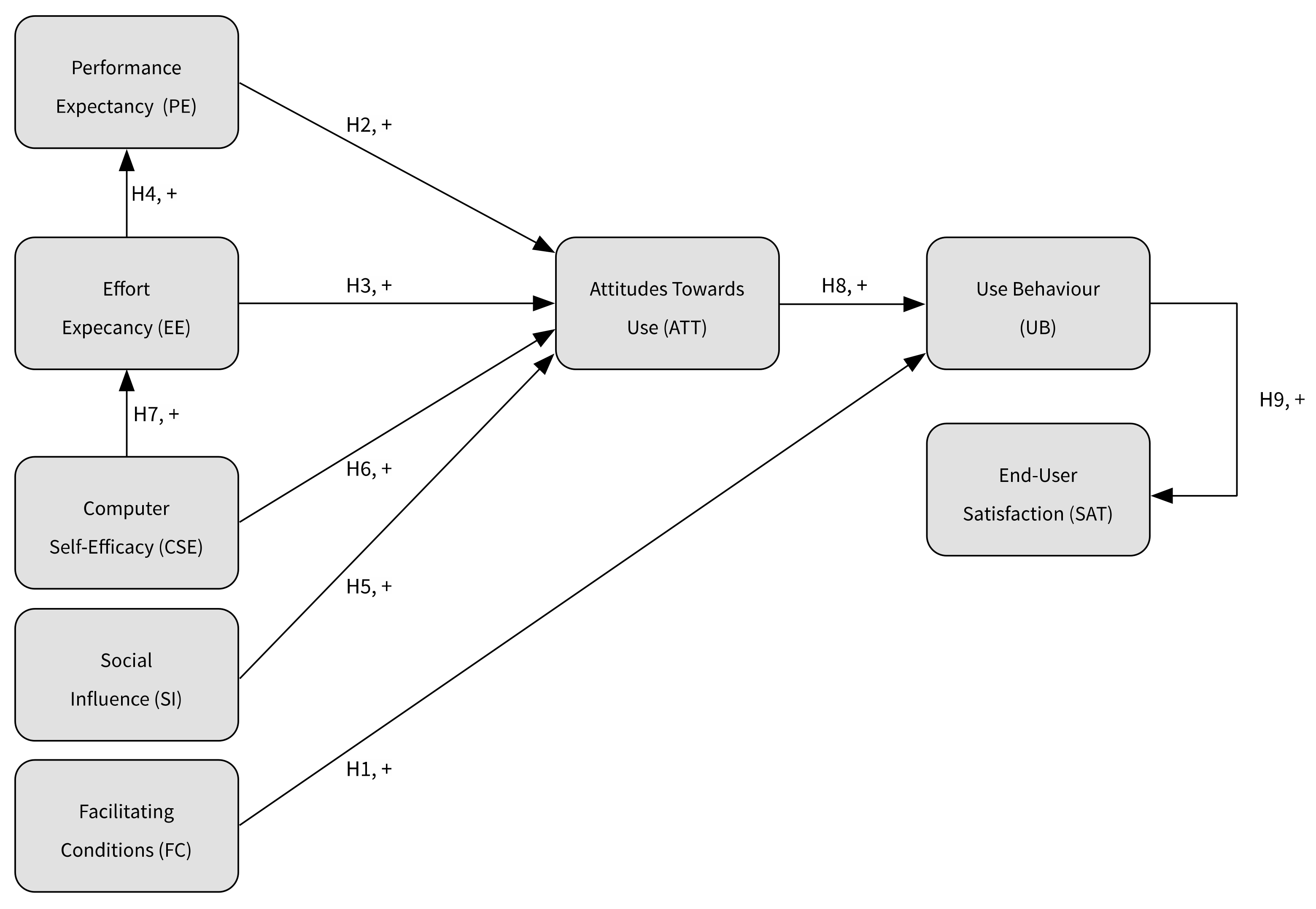

2.2. Towards the Construction of a Research Model, Based on the UTAUT

3. Methods

3.1. Design and Context

3.2. Methods for Component Study 1: Observable Use

3.3. Methods for Component Study 2: Testing the Research Model

3.4. Methods for Component Study 3: Care Professionals’ Experiences

- location-wide functionalities were nearly never used (e.g., cameras);

- the number of logins was higher than the number of functionalities used;

- protocols were rarely used, and following a pilot study, the organizations had questions about the added value of this functionality.

4. Results

4.1. Results of Component Study 1: Actual Use

4.1.1. Information About Users of the Devices

4.1.2. Information About Actual Use of the Devices

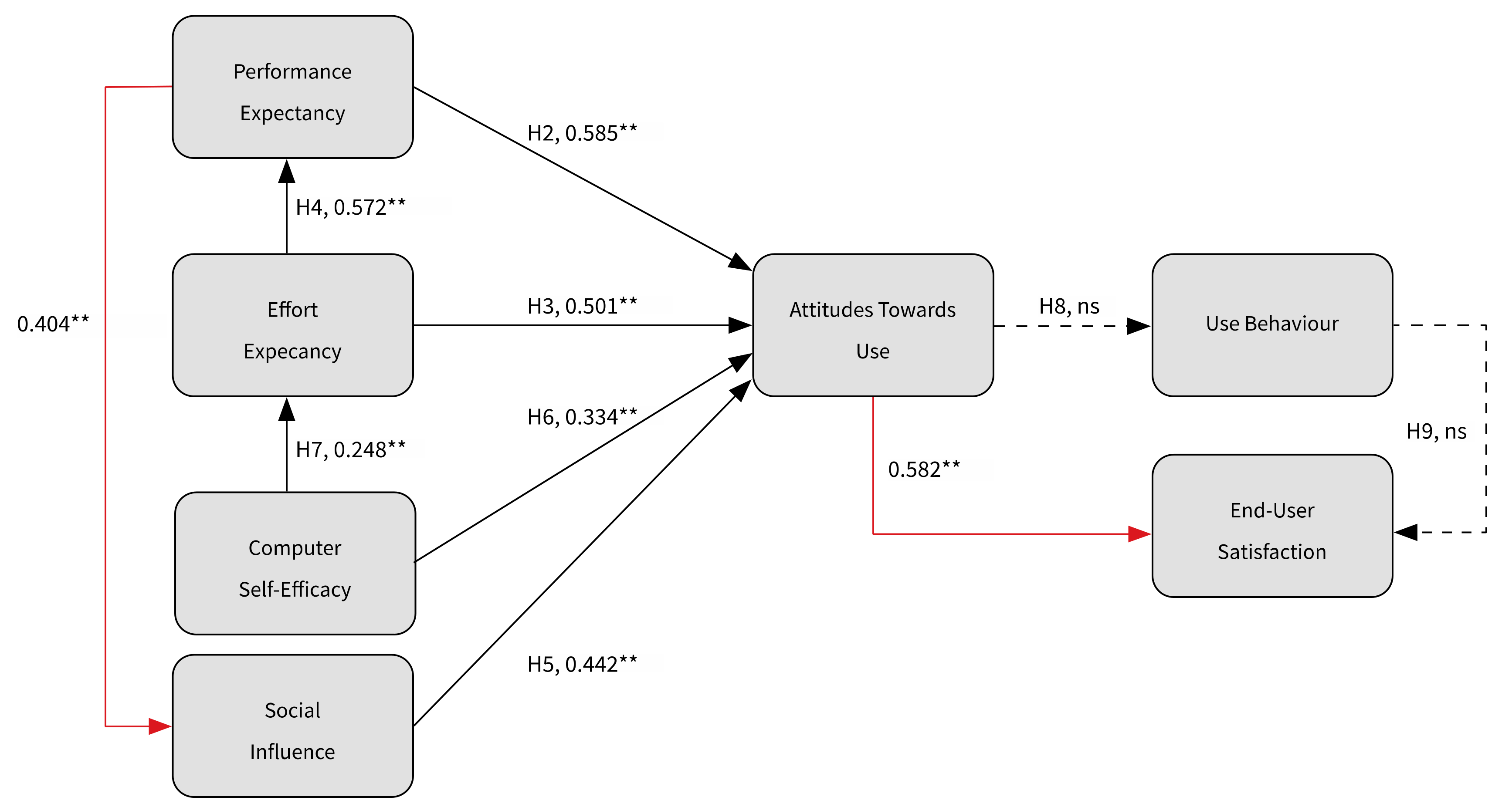

4.2. Results of Component Study 2: Testing the Research Model

4.2.1. Sample Demographics

4.2.2. Reliability of the Constructs and Their Correlation

4.2.3. Correlation and Regression Analysis

4.3. Results of Component Study 3: The Experiences of Care Professionals (End Users)

- information can be consulted in a client’s room;

- the devices are easy to use;

- the cameras can be viewed from a distance.

- client information that can be consulted while in a client’s room is insufficient; important information is missing, such as wishes concerning resuscitation, contacts, their physician’s contact details, etc.;

- the devices’ operating speed is too low, and it is often impossible to log in. Solutions in these respects are certainly required;

- add report functionality to the devices. The care professionals can only consult information. It would be an improvement if they could use the devices to add information, such as measurements (e.g., blood pressure and weight) and care-specific reports;

- make the devices portable. The devices are mounted in the living room and are not at an ergonomically acceptable height.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Limitations and Recommendations for Further Research

5.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maillet, E.; Mathieu, L.; Sicotte, C. Modeling factors explaining the acceptance, actual use, and satisfaction of nurses using an electronic patient record in acute care settings: An extension of the UTAUT. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2015, 84, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archibald, M.M.; Barnard, A. Futurism in nursing: Technology, robotics and the fundamentals of care. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 2473–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, T.; Brailer, D. The Decade of Health Information Technology: Delivering Consumer-Centric and Information-Rich Health Care; Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsouris, D.D.; Lozakidou, A.A. Concepts and trends in healthcare information systems. Annals of Information Systems 2014, 16, 1934–3221. [Google Scholar]

- van Hoof, J.; Demiris, G.; Wouters, E.J.M. Handbook of Smart Homes, Health Care and Well-Being; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, B.D.; Resnick, A.; Lin, M.; Handler, S. Development of an applied framework for understanding health information technology in nursing homes. JAMDA J. Post-Acute Long-Term Care Med. 2016, 17, 434–440. [Google Scholar]

- Sponselee, A.A.G. Acceptance and Effectiveness of Telecare Services from the End-User Perspective; Technische Universiteit: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aggelidis, V.P.; Chatzoglou, P.D. Using a modified technology acceptance model in hospitals. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2009, 78, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Veer, A.J.E.; Francke, A.L. Ervaringen van Verpleegkundigen en Verzorgenden Met Nieuwe Technologieën in de Zorg; NIVEL: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Lee, K.; Hwang, H.; Yoo, S. Analysis of the factors influencing healthcare professionals adoption of mobile electronic medical record (EMR) using the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) in a tertiary hospital. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2016, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, K.; Sheikh, A. Organizational issues in the implementation and adoption of health information technology innovations: An interpretative review. Int. J. Med Inform. 2013, 82, e73–e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strudwick, G. Predicting nurses’ use of healthcare technology using the technology acceptance model: An Integrative Review. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2015, 33, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezboruah, C.; Paulson, D.; Smith, J. Management attitudes and technology adoption in long-term care facilities. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2014, 28, 344–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkhoven, F.; Van der Aalst, M. Zorg Sectorbeschrijving [Research in Care and Cure]; UWV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, C.E.; Donthu, N. Using the technology acceptance model to explain how attitudes determine Internet usage: The role of perceived access barriers and demographics. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, R.J.; Karsh, B. The technology acceptance model: Its past and its future in health care; J. Biomed. Inform. 2010, 43, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Kozar, K.A.; Larsen, K.R.T. The technology acceptance model: Past, present and future. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2003, 12, 752–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouch, S.B. Van Adoptie naar Acceptatie van Nieuwe Technologie [From Adoption to Acceptance of New Technology]; Enschede: Saxion, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Cruz, A.M.; Rincon, A.D.; Buttar, V.; Ranson, Q.; Goertzen, D. What factors determine therapists’ acceptance of new technologies for rehabilitation—A study using the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 37, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.D.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): A literature review. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2015, 28, 443–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pynoo, B.; Devolder, P.; Duyck, W.; van Braak, J.; Sijnave, B.; Duyck, P. Do hospital physicians’ attitudes change during PACS implementation? A cross-sectional acceptance study. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2012, 81, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, D.; Vermeulen, B.; Declercq, A. Healthcare professionals acceptance of BelRAI, a web-based system enabling person-centred recording and data sharing across care settings with interRAI instruments: A UTAUT analysis. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2013, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladan, M.A.; Wharrad, H.; Windle, R. Towards understanding healthcare professionals’ adoption and use of technologies in clinical practice: Using Q-methodology and models of technology acceptance. J. Innov. Health Inform. 2018, 25, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, PA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.; Kuo, Y.; Ru Wang, S.; Chuang, B.; Tsai, C. A Study of Personal Health Record User’s Behavioral Model Based on the PMT and UTAUT Integrative Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, Y.; Nawata, K.; Huang, C. An exploration and confirmation of the factors influencing adoption of IoT-based wearable fitness trackers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N.P.; Jeyeraj, A.; Celement, M.; Williams, M.D. Re-examining the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): Toward a revised theoretical model. Inf. Syst. Front. 2017, 21, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khechine, H.; Ndjambou, P.; Lakhal, S. A meta-analysis of the UTAUT model: Eleven years later. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2016, 33, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nictiz Zorg op Afstand. Het Perspectief van de Zorgprofessionals in de Langdurige Zorg; Een Verkenning Nictiz: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, S.Y.; Chang, C.M.; Kuo, S.R. User acceptance of mobile e-government services: An empirical study. Govern. Inform. Q. 2013, 30, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nriprendra, P.R.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Lal, B.; Williams, M.D.; Clement, M. Citizens’ adoption of an electronic government system: Towards a unified view. Inf. Syst. Front. 2017, 19, 549–568. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Towards a Unifying theory of behavioural change. Psycho Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melas, C.D.; Zampetakis, L.A.; Dimopoulou, A.; Moustakis, V. Modeling the acceptance of clinical information systems among hospital medical staff: An extended TAM model. J. Biomed. Inform. 2011, 44, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, A. Self-Efficacy and Health. Behav. Res. Ther. 1985, 23, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, T.W.; Lending, D. Will they adopt? Effects of Privacy and Accuracy. J. Comp. Inform. Syst. 2010, 50, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.A.; Massey, A.P.; Montoya-Weiss, M.M.; Burkman, J.R. Do I really have to? User acceptance of mandated technology. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2002, 11, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Methoden en Technieken van Onderzoek [Research Methods and Techniques]; Pearson Benelux: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ISOQOL. Vertalen van PROMs. Available online: http://www.isoqol.nl/taxonomy/term/20 (accessed on 6 November 2018).

- Straub, D.W.; Burton-Jones, A. Veni, vidi, vici: Breaking the TAM logjam. J. Assoc. Inform. Syst. 2007, 8, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- De Vocht, A. Basishandboek SPSS 10 Voor Windows 98/ME/2000 2000 [Basic Handbook on SPSS 10 for Windows 98/ME/2000]; Bijleveld Press: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Deterding, N.M.; Waters, M.C. Flexible Coding of In-depth Interviews: A Twenty-first-century Approach. Sociol. Methods Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; Tavory, I. Theory Construction in Qualitative Research: From Grounded Theory to Abductive Analysis. Sociol. Theory 2012, 30, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelby, L.B. Beyond Cronbach’s alpha: Considering confirmatory factor analysis and segmentation. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2011, 16, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenthal, K.M. An Introduction to Psychological Tests and Scale; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hsien-Cheng, L. Nurses’ satisfaction with using nursing information systems from technology acceptance model and information systems success model perspectives. A reductionist approach. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2017, 35, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Langhan, M.L.; Riera, A.; Kurtz, J.C.; Schaeffer, P.; Asnes, A.G. Implementation of newly adopted technology in acute care settings: A qualitative analysis of clinical staff. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 2015, 39, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P.A. Decomposition and crossover effects in the theory of planned behaviour: A study of consumer adoption. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 12, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, M.; Beranek, P.M.; Konsynski, B.R. Usefulness and ease of use: Field study evidence regarding tasks considerations. Decis. Support. Syst. 1995, 13, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Basden, A. Non-Discretionary Use of Information System and the Technology Acceptance Model; University of Salford: Manchester, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffers, J.; Mordant-Dols, A. Transformational leadership and professionals’ willingness to change: A multiple case study in project management organisations. Hum. Resour. Manag. Res. 2015, 5, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

| Components of This Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Component 1 | Component 2 | Component 3 | |

| Observable use | Testing of research model | Care professionals’ experiences | |

| Type of research | Quantitative | Quantitative | Qualitative |

| Research design | Longitudinal | Cross-sectional | Multiple case study |

| Methods | Logfiles | Questionnaires | Semi-structured interviews |

| Total (n = 878) | Care org. A (n = 444) | Care org. B (n = 434) | |

| Avg. age (min–max) | 42.5 (17–66) | 42 (17–65) | 43 (18–66) |

| Avg. contract hrs (min–max) | 24.5 (0–36) | 23 (0–36) | 26 (0–36) |

| Female (F) Male (M) | 92% (n = 845) F 8% (n = 70) M | 94% (n = 417) F 6% (n = 27) M | 91% (n = 428) F 9% (n = 43) M |

| Total (n = 933) | Care org. A (n = 444) | Care org. B (n = 489) | |

| Care aide; level 1 (%) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Care and welfare assistant; level 2 (%) | 16 | 22 | 11 |

| Individual health care assistant; level 3 (%) | 73 | 63 | 82 |

| Nurse; level 4 (%) | 6 | 10 | 2 |

| Nurse; level 5 (%) | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Unknown (%) | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Morning T1–T4 | Afternoon T1–T4 | Evening T1–T4 | Night T1–T4 | Total T1–T4 | Avg. Use Per Day, Per Moment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organization B (n = 489) | Client camera on location | 115 (5%) | 11 (1%) | 292 (13%) | 1864 (82%) | 2281 | 4.7 |

| Client camera, location-wide | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 | 0 A | |

| Peripheral camera | 2 (2%) | 3 (4%) | 8 (10%) | 68 (84%) | 81 | 0.17 | |

| Peripheral camera, location-wide | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Entry camera | 5 (31%) | 5 (31%) | 4 (25%) | 2 (2%) | 16 | 0.03 | |

| Electronic patient records | 93 (78%) | 7 (6%) | 16 (13%) | 3 (4%) | 119 | 0.24 | |

| Call-and-response logging | 12 (9%) | 7 (6%) | 26 (20%) | 82 (65%) | 127 | 0.26 | |

| Vilans protocols | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Organization A (n = 444) | Client camera on location | 80 (9%) | 14 (2%) | 100 (11%) | 719 (79%) | 914 | 2.06 |

| Client camera, location-wide | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 | 0 A | |

| Peripheral camera | 3 (2%) | 5 (4%) | 14 (11%) | 101 (82%) | 123 | 0.28 | |

| Peripheral camera, location-wide | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Entry camera | 3 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (26%) | 21 (62%) | 34 | 0.08 | |

| Electronic patient records | 468 (70%) | 45 (7%) | 119 (18%) | 38 (6%) | 669 | 1.51 | |

| Call-and-response logging | 9 (10%) | 5 (5%) | 17 (18%) | 61 (66%) | 93 | 0.21 | |

| Vilans protocols | 0 A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Total (n = 933) | Client camera on location | 185 (6%) | 25 (1%) | 392 (12%) | 2,583 (81%) | 3,185 | 3.4 |

| Client camera, location-wide | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 | 0 A | |

| Peripheral camera | 5 (2%) | 8 (4%) | 22 (11%) | 169 (83%) | 204 | 0.22 | |

| Peripheral camera, location-wide | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Entry camera | 8 (16%) | 5 (10%) | 13 (27%) | 23 (47%) | 49 | 0.05 | |

| Electronic patient records | 561 (71%) | 53 (7%) | 135 (17%) | 41 (5%) | 790 | 0.85 | |

| Call-and-response logging | 21 (10%) | 12 (5%) | 43 (20%) | 143 (65%) | 219 | 0.23 | |

| Vilans protocols | 0 A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Variable | N | Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitating Conditions (FCs) | 180 | 4 | 0.444 |

| Performance Expectancy (PE) | 180 | 4 | 0.859 |

| Effort Expectancy (EE) | 180 | 4 | 0.879 |

| Social Influence (SI) | 180 | 4 | 0.817 |

| Computer Self-Efficacy (CSE) | 180 | 4 | 0.594 |

| Attitude Toward Use (ATU) | 180 | 4 | 0.906 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brandsma, T.; Stoffers, J.; Schrijver, I. Advanced Technology Use by Care Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030742

Brandsma T, Stoffers J, Schrijver I. Advanced Technology Use by Care Professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(3):742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030742

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrandsma, Tom, Jol Stoffers, and Ilse Schrijver. 2020. "Advanced Technology Use by Care Professionals" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 3: 742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030742

APA StyleBrandsma, T., Stoffers, J., & Schrijver, I. (2020). Advanced Technology Use by Care Professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030742