Contextual Factors Influencing the MAMAACT Intervention: A Qualitative Study of Non-Western Immigrant Women’s Response to Potential Pregnancy Complications in Everyday Life

Abstract

1. Introduction

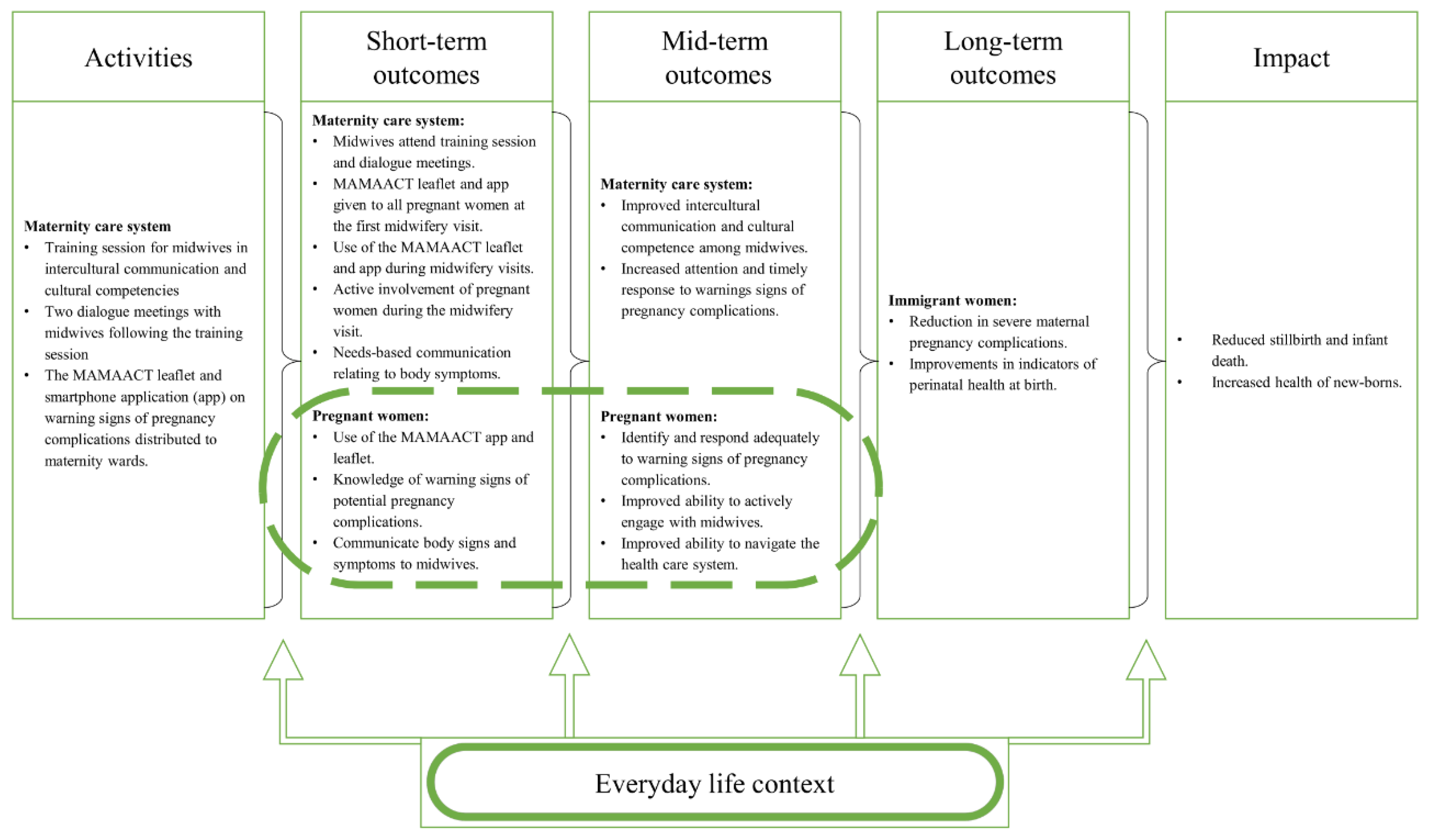

1.1. The MAMAACT Intervention

1.2. Logic Model and Study Aim

1.3. Study Setting

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment of Non-Western Immigrant Women

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Interviews with Non-Western Immigrant Women

2.4. Data Analysis

Situational Adaptation

3. Results

3.1. Sources of Knowledge during Pregnancy

3.1.1. Use of Friends and Family for Advice

“… I told them, that I hadn’t felt the baby kick, I felt nothing. They recommended eating something sweet because it would get the baby moving again”.(Pregnant woman, Syria, I21)

“…. you don’t talk about the pregnancy, they (my parents) have plenty they must to deal with”.(Pregnant woman, Iraq, I18)

“… I don’t have any close female relations or family members here. I have the two sisters of my spouse and they are a little older than me and have both given birth, but I don’t ask them (about my pregnancy). This is not something you talk about”.(Pregnant woman, Pakistan, I19)

3.1.2. Dealing with Private Matters Online

“… When I googled (my symptoms) … I was confirmed in my suspicion that I have in fact overexerted myself and I have been too tired…Plus the pressure from the baby also leads to fluid from the lower regions”.(Pregnant woman, Jordan, I7)

3.2. Containment of Pregnancy Warning Signs

Suppressing Symptoms and Postponing Medical Attention

“I am always in pain. I can’t always cope… I get exhausted because there is too much work”.(Pregnant woman, Somalia, I3)

“…My spouse told me, you can’t go to work, you were ill yesterday. I tell him no! I have to go to work because two of my colleagues were off work ill…It won’t work if I stay home… so I went to work…when I came home it was really bad, a lot of pain in my stomach…I had pain for four to five minutes at a time. I have never tried that before, I got scared, will I deliver now, before my due date?”.(Pregnant woman, Morocco, I20)

“…it (my midwifery appointments) depend on what is feasible for my husband…I get to ask about things (symptoms) I don’t understand. I like when he is present…”.(Pregnant woman Syria, I21)

3.3. Barriers during the Onset of Acute Illness

3.3.1. Someone to Advocate for Medical Assistance Needs

“… I am worried. At the asylum center, many people could help, many people living together…women who could help, who had children, so they knew. They helped me a lot because eight families lived in every building. There were also people working in the office who could step in and help me, call for an ambulance…But now no one”.(Pregnant woman, Syria, I16)

3.3.2. Looking After Existing Children

“…What am I going to do, tell my children ‘wake up, help me!’. They will be asleep and they won’t hear me…I will need my telephone…will need to sit on the floor, so the baby won’t fall out…you take the baby out this way…they (the videos) showed me what to do if you are all alone”.(Pregnant woman, Yemen, I5)

3.4. Previous Situations with Maternity Care Providers

3.4.1. Concerns of Maternity Care Providers Reactions

“I told my doctor before and also the midwife during the pregnancy, ‘I cannot birth normally’…when I was in Syria…she (the doctor) told me ‘you cannot birth normally’…there was not enough room in my pelvis…It makes me absolutely angry…the (Danish) doctor’s job is to listen to me…”.(Pregnant woman, Syria, I17)

“…Three hours I am sitting freezing in the waiting room…no one comes and tells me I can lie down or brings me a blanket, nothing! I would rather avoid having to engage with them and ask them (maternity care providers)…it’s neglect of care, no one asks me if I would like to stay the night at the hospital…I am pregnant, I have no one, no network, someone beside me to take care of me”.(Pregnant woman Syria, I13)

3.4.2. Preferring Self-Care

“… In week 24 I call the ward and say… ’the baby is not very active’. They tell me ‘you know this is normal at this time of the pregnancy’. I ask them ‘could you just examine me for a few minutes? I can come in’…They tell me ‘no, if you come in, we are only able to listen to the heartbeat, and if it’s fine, that’s it’. I tell them ‘okay then I won’t bother. I have a device’. I am able (to listen to the heartbeat)”.(Pregnant woman, Pakistan, I12)

4. Discussion

4.1. Having Informal Social Relations

4.2. Containment of Signs and Symptoms in Everyday Situations

4.3. The Importance of Relations with Maternity Care Providers

4.4. Multiple Routes to a Delayed Response to Pregnancy Complications

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Danmarks Statistik. Indvandrere i Danmark 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.dst.dk/Site/Dst/Udgivelser/GetPubFile.aspx?id=29445&sid=indv2018 (accessed on 13 November 2019).

- Boerleider, A.W.; Wiegers, T.A.; Manniën, J.; Francke, A.L.; Devillé, W.L.J.M. Factors affecting the use of prenatal care by non-western women in industrialized western countries: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Improving the Health Care of Pregnant Refugee and Migrant Women and Newborn Children [Technical Guidance on Refugee and Migrant Health]; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018; pp. 1–40. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/388362/tc-mother-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Binder, P.; Borné, Y.; Johnsdotter, S.; Essén, B. Shared language is essential: Communication in a multiethnic obstetric care setting. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17, 1171–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higginbottom, G.M.A.; Hadziabdic, E.; Yohani, S.; Paton, P. Immigrant women’s experience of maternity services in Canada: A meta-ethnography. Midwifery 2014, 30, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saastad, E.; Vangen, S.; Frøen, J.F. Suboptimal care in stillbirths – a retrospective audit study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2007, 86, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esscher, A.; Binder-Finnema, P.; Bødker, B.; Högberg, U.; Mulic-Lutvica, A.; Essén, B. Suboptimal care and maternal mortality among foreign-born women in Sweden: Maternal death audit with application of the ‘migration three delays’ model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalonga-Olives, E.; Kawachi, I.; von Steinbüchel, N. Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes among Immigrant Women in the US and Europe: A Systematic Review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2017, 19, 1469–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keygnaert, I.; World Health Organization; Regional Office for Europe; Health Evidence Network. What Is the Evidence on the Reduction of Inequalities in Accessibility and Quality of Maternal Health Care Delivery for Migrants? A Review of the Existing Evidence in the WHO European Region; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Urquia, M.L.; Glazier, R.H.; Mortensen, L.; Nybo-Andersen, A.-M.; Small, R.; Davey, M.-A.; Rööst, M.; Essén, B. Severe maternal morbidity associated with maternal birthplace in three high-immigration settings. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonkers, M.; Richters, A.; Zwart, J.; Öry, F.; van Roosmalen, J. Severe maternal morbidity among immigrant women in the Netherlands: patients’ perspectives. Reprod. Health Matters 2011, 19, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villadsen, S.F.; Mortensen, L.H.; Andersen, A.M.N. Ethnic disparity in stillbirth and infant mortality in Denmark 1981–2003. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 63, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villadsen, S.F.; Sievers, E.; Andersen, A.-M.N.; Arntzen, A.; Audard-Mariller, M.; Martens, G.; Ascher, H.; Hjern, A. Cross-country variation in stillbirth and neonatal mortality in offspring of Turkish migrants in northern Europe. Eur. J. Public Health 2010, 20, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.M.; Caldas, J.; Ayres-de-Campos, D.; Salcedo-Barrientos, D.; Dias, S. Maternal healthcare in migrants: A systematic review. Matern. Child Health J. 2013, 17, 1346–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.; Manniën, J.; te Velde, S.J.; Klomp, T.; Hutton, E.K.; Brug, J. Socio-demographic inequalities across a range of health status indicators and health behaviours among pregnant women in prenatal primary care: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 261. Available online: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/15/261 (accessed on 1 November 2019). [CrossRef]

- Binder, P.; Johnsdotter, S.; Essén, B. Conceptualising the prevention of adverse obstetric outcomes among immigrants using the ‘three delays’ framework in a high-income context. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2028–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Due, P. Social relations: Network, support and relational strain. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 48, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.F.; Audrey, S.; Barker, M.; Bond, L.; Bonell, C.; Hardeman, W.; Moore, L.; O’Cathain, A.; Tinati, T.; Wight, D.; et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015, 350, h1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villadsen, S.F.; Mortensen, L.H.; Andersen, A.-M.N. Care during pregnancy and childbirth for migrant women: How do we advance? Development of intervention studies--the case of the MAMAACT intervention in Denmark. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 32, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villadsen, S.F. The MAMAACT Intervention [MAMAACT]. 2018. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03751774 (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- Akhavan, S.; Edge, D. Foreign-Born Women’s Experiences of Community-Based Doulas in Sweden—A Qualitative Study. Health Care Women Int. 2012, 33, 833–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwin, Z.; Green, J.; McLeish, J.; Willmot, H.; Spiby, H. Evaluation of trained volunteer doula services for disadvantaged women in five areas in England: women’s experiences. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggs, E.; Muyeen, S.; Brown, S.; Dawson, W.; Petschel, P.; Tardiff, W.; Norman, F.; Vanpraag, D.; Szwarc, J.; Yelland, J. Cultural safety and belonging for refugee background women attending group pregnancy care: An Australian qualitative study. Birth 2017, 44, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lathrop, B. A Systematic Review Comparing Group Prenatal Care to Traditional Prenatal Care. Nurs. Womens Health 2013, 17, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, a1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawson, R.; Tilley, N. Realistic Evaluation; Sage: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; p. 235. [Google Scholar]

- Bonell, C.; Fletcher, A.; Morton, M.; Lorenc, T.; Moore, L. Realist randomised controlled trials: A new approach to evaluating complex public health interventions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2299–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, B.; Frohlich, K.L.; Cargo, M. Context as a Fundamental Dimension of Health Promotion Program Evaluation. In Health Promotion Evaluation Practices in the Americas: Values and Research; Potvin, L., McQueen, D.V., Hall, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 299–317. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew, J. Representing Space: Space, Scale and Culture in Social Science. In Place/Culture/Representation; Duncan James, S., Ley, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 251–271. [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen, A.; Brot, C.; Danmark, S. Anbefalinger for Svangreomsorgen. 2. Udgave, 1. Oplag; Sundhedsstyrelsen: København, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.; Thorogood, N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; p. 342. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S.; Brinkmann, S. Interview: Det Kvalitative Forskningsinterview Som Håndværk; Hans Reitzels Forlag: København, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K. Kvalitative Forskningsmetoder for Medisin og Helsefag: En Innføring; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, G.F.; Evans, R.E. What theory, for whom and in which context? Reflections on the application of theory in the development and evaluation of complex population health interventions. SSM Popul. Health 2017, 3, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo, A.A. An illness behaviour paradigm: A conceptual exploration of a situational–adaptation perspective. Soc. Sci. Med. 1984, 19, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubos, R.J. Mirage of Health; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Gannik, D. Situational disease: Elements of a social theory of disease based on a study of back trouble. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care Suppl. 2002, 20, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, U.M.; Cleal, B.; Willaing, I.; Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T. Managing type 1 diabetes in the context of work life: A matter of containment. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 219, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R.S.; Paarup, B.; Vedsted, P.; Bro, F.; Soendergaard, J. ‘Containment’ as an analytical framework for understanding patient delay: A qualitative study of cancer patients’ symptom interpretation processes. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaaka, G.; Schauer Eri, T. Doing midwifery between different belief systems. Midwifery 2008, 24, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, L.; Pelaez, S.; Edwards, N.C. Refugees, asylum-seekers and undocumented migrants and the experience of parenthood: A synthesis of the qualitative literature. Glob. Health 2017, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, B.N.; Bowen, K.; de Grey, R.K.; Mikel, J.; Fisher, E.B. Social Support and Physical Health: Models, Mechanisms, and Opportunities. In Principles and Concepts of Behavioural Medicine: A Global Handbook; Fisher, E.B., Christensen, A.J., Ehlert, U., Guo, Y., Oldenburg, B., Snoek, F.J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 341–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, A.; Benson, P. Anthropology in the Clinic: The Problem of Cultural Competency and How to Fix It. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, e294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomeen, J.; Redshaw, M. Ethnic minority women’s experience of maternity services in England. Ethn. Health 2013, 18, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.; Gao, H.; Redshaw, M. Experiencing maternity care: The care received and perceptions of women from different ethnic groups. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goguikian Ratcliff, B.; Pereira, C. L’alliance thérapeutique triadique dans une psychothérapie avec un interprète: Un concept en quête de validation. Prat. Psychol. 2019, 25, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, G.; Abel, T. Capital interplays and social inequalities in health. Scand. J. Public Health 2019, 47, 631–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Maternity Ward | Annual Births Above or Below 3000 | Location in Denmark East/West | Populations Served Urban/Provincial | Immigrant Targeted Antenatal Care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Above | East | Urban | No |

| 2 | Below | East | Provincial | Yes |

| 3 | Above | West | Urban | Yes |

| 4 | Below | West | Provincial | No |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johnsen, H.; Christensen, U.; Juhl, M.; Villadsen, S.F. Contextual Factors Influencing the MAMAACT Intervention: A Qualitative Study of Non-Western Immigrant Women’s Response to Potential Pregnancy Complications in Everyday Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031040

Johnsen H, Christensen U, Juhl M, Villadsen SF. Contextual Factors Influencing the MAMAACT Intervention: A Qualitative Study of Non-Western Immigrant Women’s Response to Potential Pregnancy Complications in Everyday Life. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(3):1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031040

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohnsen, Helle, Ulla Christensen, Mette Juhl, and Sarah Fredsted Villadsen. 2020. "Contextual Factors Influencing the MAMAACT Intervention: A Qualitative Study of Non-Western Immigrant Women’s Response to Potential Pregnancy Complications in Everyday Life" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 3: 1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031040

APA StyleJohnsen, H., Christensen, U., Juhl, M., & Villadsen, S. F. (2020). Contextual Factors Influencing the MAMAACT Intervention: A Qualitative Study of Non-Western Immigrant Women’s Response to Potential Pregnancy Complications in Everyday Life. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031040