Effects of Aerobic and Resistance Exercise Interventions on Cognitive and Physiologic Adaptations for Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Control Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

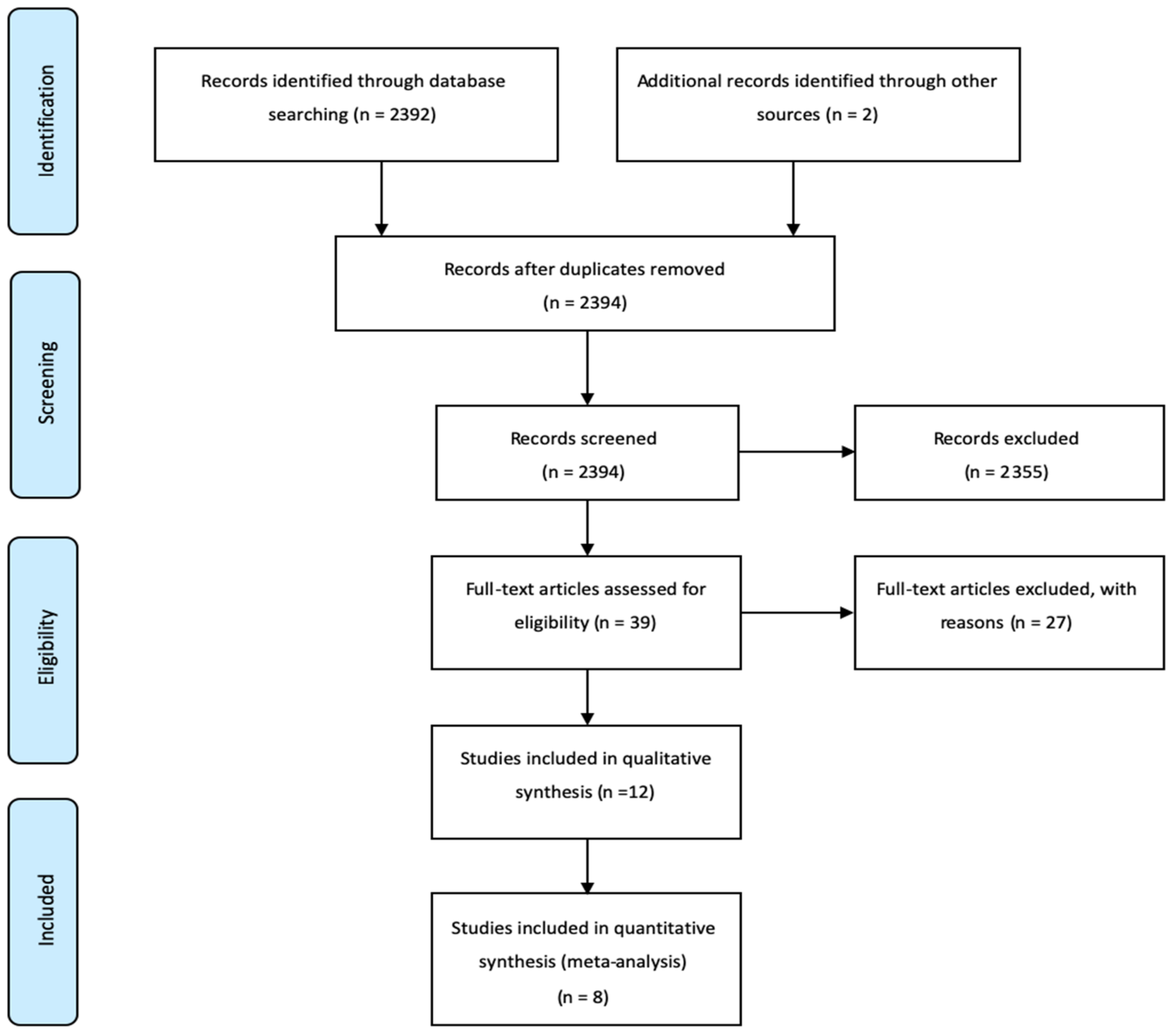

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Searching Processes

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

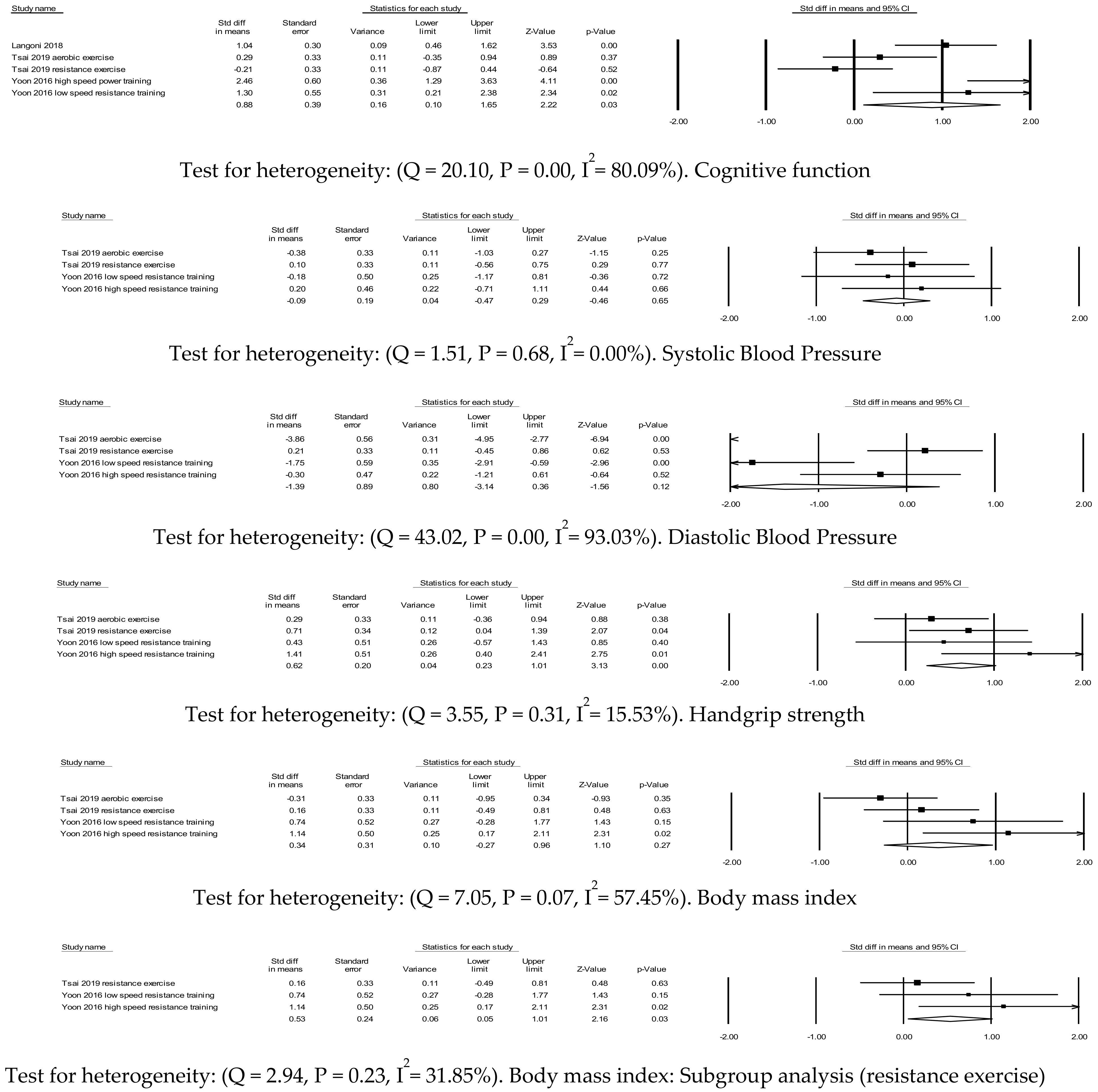

3.1. Effects of Exercise Interventions on Cognitive Function for Older Adults with MCI

3.2. Effects of Exercise Interventions on Blood Pressure for Older Adults with MCI

3.3. Effects of Exercise Interventions on Body Mass Index for Older Adults with MCI

3.4. Effects of Exercise Interventions on Handgrip Strength for Older Adults with MCI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Contents | Baker (2010) | Hu (2014) | Lautenschlager (2008) | Liu-Ambrose (2016) | Scherder (2005) | Tao (2019) | Ten Brink (2015) | Brown (2009) | Langoni (2018) | Yoon (2017) | Nagamatsu (2013) | Teixeira (2018) | Tsai (2019) | Van Uffelen (2008) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Detailed description of the type of exercise equipment | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2. Detailed description of the qualifications, expertise and/or training | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3. Describe whether exercises are performed individually or in a group | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4. Describe whether exercises are supervised or unsupervised; how they are delivered | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5. Detailed description of how adherence to exercise is measured and reported | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6. Detailed description of motivation strategies | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7. Detailed description of the decision rule(s) for determining exercise progression | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7a. Detailed description of how the exercise program was progressed | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8. Detailed description of each exercise to enable replication | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 9. Detailed description of any home program component | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10. Describe whether there are any non-exercise components | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11. Describe the type and number of adverse events that occur during exercise | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 12. Describe the setting in which the exercises are performed | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 13. Detailed description of the exercise intervention | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 14a. Describe whether the exercises are generic (one size fits all) or tailored | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 14b. Detailed description of how exercises are tailored to the individual | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15. Describe the decision rule for determining the starting level | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 16a. Describe how adherence or fidelity is assessed/measured | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16b. Describe the extent to which the intervention was delivered as planned | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

References

- Gauthier, S.; Reisberg, B.; Zaudig, M.; Petersen, R.C.; Ritchie, K.; Broich, K.; Belleville, S.; Brodaty, H.; Bennett, D.; Chertkow, H.; et al. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet 2006, 367, 1262–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, M.; Pihlsgard, M.; Elmstahl, S. Prevalence and Incidence of Mild Cognitive Impairment across Subtypes, Age, and Sex. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2019, 47, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, N.M.; Shahar, S.; Yahya, H.M.; Din, N.C.; Singh, D.K.A.; Azahadi, O. Incidence and predictors of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) within a multi-ethnic Asian populace: A community-based longitudinal study. BMC Public Heal. 2019, 19, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, A.; Punhani, N.; Bala, M.; Arora, S.; Gill, G.S.; Dewan, N. The prevalence and pattern of cavitated carious lesions in primary dentition among children under 5 years age in Sirsa, Haryana (India). J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2015, 5, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karssemeijer, E.G.A.; Bossers, W.J.R.; Aaronson, J.A.; Kessels, R.P.C.; Rikkert, M.G.M.O. The effect of an interactive cycling training on cognitive functioning in older adults with mild dementia: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, N.; Singh, M.A.F.; Sachdev, P.S.; Valenzuela, M. The Effect of Exercise Training on Cognitive Function in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 21, 1086–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karssemeijer, E.G.A.; Aaronson, J.A.; Bossers, W.J.; Smits, T.; Olde Rikkert, M.G.M.; Kessels, R.P.C. Positive effects of combined cognitive and physical exercise training on cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: A meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 40, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, G.; Zhou, W.; Xia, R.; Tao, J.; Chen, L. Aerobic Exercises for Cognition Rehabilitation following Stroke: A Systematic Review. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2016, 25, 2780–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loprinzi, P.D.; Blough, J.; Ryu, S.; Kang, M. Experimental effects of exercise on memory function among mild cognitive impairment: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Physician Sportsmed. 2018, 47, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, D.; Yu, D.S.F.; Li, P.W.; Lei, Y. The effectiveness of physical exercise on cognitive and psychological outcomes in individuals with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 79, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastianetto, S. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Effects of aerobic exercise on mild cognitive impairment: A controlled trial. Fac. Opin. Post Publ. Peer Rev. Biomed. Lit. 2010, 67, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamatsu, L.S.; Chan, A.; Davis, J.C.; Beattie, B.L.; Graf, P.; Voss, M.W.; Sharma, D.; Liu-Ambrose, T. Physical Activity Improves Verbal and Spatial Memory in Older Adults with Probable Mild Cognitive Impairment: A 6-Month Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Aging Res. 2013, 2013, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, D.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Song, W. Effects of Resistance Exercise Training on Cognitive Function and Physical Performance in Cognitive Frailty: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Nutr. Heal. Aging 2018, 22, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.-L.; Sun, H.S.; Kuo, Y.-M.; Pai, M.-C. The Role of Physical Fitness in Cognitive-Related Biomarkers in Persons at Genetic Risk of Familial Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langoni, C.D.S.; Resende, T.L.; Barcellos, A.B.; Cecchele, B.; Knob, M.S.; Silva, T.D.N.; da Rosa, J.N.; Diogo, T.S.; Filho, I.; Schwanke, C.H.A. Effect of Exercise on Cognition, Conditioning, Muscle Endurance, and Balance in Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2019, 42, E15–E22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammisuli, D.M.; Innocenti, A.; Franzoni, F.; Pruneti, C. Aerobic exercise effects upon cognition in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Ital. Biol. 2017, 155, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, P.A.; Buchman, A.S.; Wilson, R.S.; Leurgans, S.E.; Bennett, D.A. Association of Muscle Strength With the Risk of Alzheimer Disease and the Rate of Cognitive Decline in Community-Dwelling Older Persons. Arch. Neurol. 2009, 66, 1339–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, S.C.; Dionne, C.E.; Underwood, M.; Buchbinder, R. Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT): Explanation and Elaboration Statement. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1428–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.K.; Liu-Ambrose, T.; Tate, R.; Lord, S.R. The effect of group-based exercise on cognitive performance and mood in seniors residing in intermediate care and self-care retirement facilities: A randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.-P.; Guo, Y.-H.; Wang, F.; Zhao, X.-P.; Zhang, Q.-H.; Song, Q.-H. Exercise improves cognitive function in aging patients. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 7, 3144–3149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Incorrect Data in: Effect of Physical Activity on Cognitive Function in Older Adults at Risk for Alzheimer Disease: A Randomized Trial. JAMA 2009, 301. [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Xia, R.; Li, M.; Huang, M.; Li, S.; Park, J.; Wilson, G.; Lang, C.; et al. Mind-body exercise improves cognitive function and modulates the function and structure of the hippocampus and anterior cingulate cortex in patients with mild cognitive impairment. NeuroImage Clin. 2019, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinke, L.F.T.; Bolandzadeh, N.; Nagamatsu, L.S.; Hsu, C.L.; Davis, J.C.; Miran-Khan, K.; Liu-Ambrose, T. Aerobic exercise increases hippocampal volume in older women with probable mild cognitive impairment: A 6-month randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Uffelen, J.G.Z.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; Van Mechelen, W.; Hopman-Rock, M. Walking or vitamin B for cognition in older adults with mild cognitive impairment? A randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2008, 42, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherder, E.; Van Paasschen, J.; Deijen, J.-B.; Van Der Knokke, S.; Orlebeke, J.F.K.; Burgers, I.; Devriese, P.-P.; Swaab, D.F.; Sergeant, J.A. Physical activity and executive functions in the elderly with mild cognitive impairment. Aging Ment. Heal. 2005, 9, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.V.L.; Ribeiro de Rezende, T.J.; Weiler, M.; Magalhaes, T.N.C.; Carletti-Cassani, A.; Silva, T.; Joaquim, H.P.G.; Talib, L.L.; Forlenza, O.V.; Franco, M.P.; et al. Cognitive and structural cerebral changes in amnestic mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease after multicomponent training. Alzheimers Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2018, 4, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Ambrose, T.; Best, J.R.; Davis, J.C.; Eng, J.J.; Lee, P.E.; Jacova, C.; Boyd, L.A.; Brasher, P.M.; Munkacsy, M.; Cheung, W.; et al. Aerobic exercise and vascular cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. Neurology 2016, 87, 2082–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Xia, R.; Zhou, W.; Tao, J.; Chen, L. Aerobic exercise ameliorates cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W. Association of grip and knee extension strength with walking speed of older women receiving home-care physical therapy. J. Frailty Aging 2015, 4, 181–183. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, R.; Vincent, B.M.; Hackney, K.J.; Robinson-Lane, S.G.; Downer, B.; Clark, B.C. The Longitudinal Associations of Handgrip Strength and Cognitive Function in Aging Americans. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taekema, D.G.; Ling, C.H.Y.; Kurrle, S.E.; Cameron, I.D.; Meskers, C.G.M.; Blauw, G.J.; Westendorp, R.G.J.; De Craen, A.J.M.; Maier, A.B. Temporal relationship between handgrip strength and cognitive performance in oldest old people. Age Ageing 2012, 41, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.-L.; Pai, M.-C.; Ukropec, J.; Ukropcová, B. Distinctive Effects of Aerobic and Resistance Exercise Modes on Neurocognitive and Biochemical Changes in Individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2019, 16, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaidis, P.T. Cardiorespiratory power across adolescence in male soccer players. Hum. Physiol. 2011, 37, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Wuu, J.; Mufson, E.J.; Fahnestock, M. Precursor form of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and mature brain-derived neurotrophic factor are decreased in the pre-clinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2005, 93, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGeer, E.G.; McGeer, P.L. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: A field in its infancy. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010, 19, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, B.S.; Teixeira, A.L.; Ojopi, E.B.; Talib, L.L.; Mendonça, V.A.; Gattaz, W.F.; Forlenza, O.V. Higher Serum sTNFR1 Level Predicts Conversion from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2011, 22, 1305–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, C.M.; Pereira, J.R.; de Andrade, L.P.; Garuffi, M.; Talib, L.L.; Forlenza, O.V.; Cancela, J.M.; Cominetti, M.R.; Stella, F. Physical exercise in MCI elderly promotes reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and improvements on cognition and BDNF peripheral levels. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2014, 11, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author (year) | Design, Adherence | Participants | Exercise Intervention | Control | Major Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic exercise | |||||

| Baker (2010) [11] | RCT: Aerobic exercise (n = 19) vs. control (n = 10) | Exercise: Women (age 65.3 ± 9.4 years), and men (age 70.9 ± 6.7 years), and control: Women (age 74.6 ± 11.1 years) and men (age 70.6 ± 6.1 years) | 24 weeks, aerobic and stretching exercise group: 4 times/week, 40 to 60 min per session, supervised exercise (the first 8 sessions, thereafter 1 session per week per participant), daily logs tracking exercise, 75% to 85% of heart rate reserve (HRR) using a treadmill, stationary bicycle, or elliptical trainer | Control group: Stretching and balance exercise, ≥50% of HR reserve exercise | Cognition, glucose metabolism, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, trophic activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, body fat reduction, multiple tests of executive function, glucose disposal, fasting plasma levels of insulin, cortisol, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, insulin-like growth factor I, and Trails B performance |

| Hu (2014) [21] | RCT: Aerobic exercise (n = 102) vs. control (n = 102) | Age 70.03 ± 10.51 years | 24 weeks, 1 time/week, jogging for 30 min, shadowboxing for 60 min, supervised | - | Mini-mental status examination, the activity of daily living assessment, and body movement testing |

| Lautenschlage (2008) [22] | RCT: Aerobic exercise (n = 85) vs. control (n = 85) | Aged 50 years or older | 24 weeks, 3 times/week, 50 min of walking or strength exercise | Usual care condition | Alzheimer’s disease assessment, mood, and quality of life |

| Liu-Ambrose (2016) [28] | RCT: Aerobic exercise (n = 35) vs. control (n = 35) | Exercise (age 74.8 ± 8.4 years) and control (age 73.7 ± 8.3 years) | 24 weeks, 3 times/week, 60 min, 60%–70% HRR, heart rate monitor, rating of perceived exertion (RPE) of 14–15 | Usual care plus education | Executive interview, Alzheimer’s disease cooperative study-activities of daily living, 6-min walk distance, body mass index, and blood pressure |

| Scherder (2005) [26] | RCT: Aerobic exercise (n = 15), hand/face group (n = 13) vs. control (n = 15) | Walking (age 84 ± 6.38 years), hand/face group (age 89 ± 2.40 years), and control (age 86 ± 5.05 years) | 6 weeks, walking group (30 min, 3 times/week), hand/face group (15 min, 3 times/week), Tai Chi exercise (1 h, 3 times/week) | Social visits or normal social activities | Executive functions (category naming, trail-making), memory (digit span, visual memory span, Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test, verbal learning, and memory test (direct recall, delayed recall, recognition) |

| Tao (2019) [23] | RCT: Aerobic exercise (n = 20), brisk walking (n = 17), vs. control (n = 20) | Age 60 years or older | 24 weeks, 3 times/week, 60 min, 55% to 75% heart rate (Baduanjin exercise) | Did not take part in any exercise or health education | Montreal Cognitive Assessment to determine MCI, structural and functional MRI, and behavioral data analysis |

| ten Brinke (2015) [24] | RCT: Aerobic exercise (n = 24), resistance exercise (n = 26), vs. balance and tone exercise (n = 27) | Age 65 to 75 years | 24 weeks, 2 times/week, 60 min, aerobic exercise (70%–80% HRR, walking), resistance exercise (6–8 repetitions, 2 sets, 7-repetition maximal (RM), biceps curls, triceps extension, seated row, latissimus dorsi pull downs, leg press, hamstring curls, and calf raises), balance and tone exercise (stretching) | Balance and tone exercise | Pulmonary function (forced expired volume), physiological measurements (VO2peak, iPPO, 6-min walk distance, systolic BP, diastolic BP, HRmax, HRrest), FACT-L (physical well-being, social well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being, lung cancer subscale, trial outcome index, FACT-General, FACT-Lung), HADS (anxiety, depression), and steps |

| Brown (2009) [20] | RCT: Resistance exercise (n = 66), flexibility and relaxation (n = 26), vs. control (n = 34) | Exercise (age 75.5 ± 5.9 years), flexibility and relaxation (age 81.59 ± 6.9 years), and control (age 78.1 ± 6.4 years) | 52 weeks, 5 to 15 min warm-up, 40 min conditioning (resistance training exercise, static and dynamic balance exercise, activities for challenging hand-eye and foot-eye co-ordination and flexibility, walking pattern exercise (large strides, heel-toe walking, narrow-based and wide-based walking, and sidestepping), 10 min cool-down, and flexibility and relaxation (gentle bending and rotation of the joints, trunk and neck and controlled rhythmic breathing) | Did not take part in any group activity | Medical conditions (cataracts, poor hearing, cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, heart disease, vascular disease, diabetes, osteoarthritis, and osteoporosis), and medication use (4 + drugs, cardiovascular disease drugs, cardiovascular system drugs, psychoactive, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) |

| Langoni (2018) [15] | RCT: Combined exercise (n = 26) vs. control (n = 26) | Age 60 years or older | 24 weeks, 2 times/week, aerobic exercise (30 min, 60% 75 maximum heart rate) and strength exercise (30 min, 2 sets, 15 repetitions, 6 s isometric contractions, 1 min rest between sets, elbow flexion, elbow extension, external shoulder rotation, shoulder abduction, shoulder adduction, shoulder internal rotation, hip adduction, hip abduction, knee extension, knee flexion, plantar flexion, squatting, functional diagonals, knee and hip flexion-extension, hip extension, knee extension, hip abduction, hip adduction trunk flexion, plantar flexion, squatting, sit/stand from a chair | Did not take part in any exercise | Mini-mental state examination, stationary walk test, sit/stand test, and functional reach test |

| Resistance exercise | |||||

| Yoon (2017) [13] | RCT: Resistance (high speed power training, n = 14), resistance (low speed strength training, n = 9), vs. control (n = 7) | Age >60 years | 12 weeks, 2 times/week, 1 h, high-speed power training (very low tension, a rate perceived exertion of 12–13 “somewhat hard”, 2–3 sets of 12–15 repetitions), low-speed power training (high tension, a rate perceived exertion of 15–16 “hard”, 2–3 sets of 8–10 repetitions) | Kept their routine daily activities, carried out static and dynamic stretching once/week for 1 h | Cognitive test (MMSE and MoCA-K), physical function (short physical performance battery, timed up and go test, handgrip strength), and muscle strength |

| Aerobic and Resistance exercise | |||||

| Nagamatsu (2013) [12] | RCT: Aerobic exercise (n = 30), resistance exercise (n = 28), vs. control (n = 28) | Age 70–80 years | 24 weeks, 2 times/week, 60 min, aerobic exercise (70–80% HRR, heart rate monitor, Borg’s scale “talk”), and resistance exercise (bicep curls, triceps extension, seated row, latissimus dorsi pull downs, leg press, hamstring curls, calf raises, 7 RM, 2 sets of 6–8 repetitions | balance and tone (stretching, balance exercise, functional sand relaxation techniques) | Verbal memory and learning (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning test), and spatial memory performance |

| Teixeira (2018) [27] | RCT: Aerobic and resistance exercise (n = 20) vs. control (n = 20) | Age 68.3 ± 4.8 years | 24 weeks, 3 times/week, aerobic exercise (70% to 90% maximum heart rate, monitoring heart rate, 30 min, walking, jogging, circuit training, balls, dancing), resistance exercise (rubber bands, basketball, volleyball, tennis, or dancing) | Did not take part in any exercise | Volume in hippocampi, memory test, functional activities, recognition, and cardiorespiratory fitness |

| Tsai (2019) [14] | RCT: Aerobic exercise (n = 15), resistance exercise (n = 13) vs. control (n = 15) | Age 60 to 85 years | 16 weeks, aerobic exercise (a bicycle ergometer or a motor-driven treadmill, 70–75% of heart rate reserve (HRR), 30 min, a polar heart rate monitor), resistance exercise (75% RM, circuit exercise: bicep curls, vertical butterflies, leg presses, seated rowing, hamstring curls, calf raise, 3 sets, 10 repetitions with a 90 s rest between sets, and a 2-min interval between each apparatus) | Static stretching, balance (balance boards and fitness balls) | Event-related potential, circulating neuroprotective growth factors (BDNF, IGF-1, VEGF, FGF-2), inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-15) |

| van Uffelen (2008) [25] | RCT: Aerobic (n = 75) vs. control (n = 75) | Age 70 to 80 years | 52 weeks, supervised exercise, aerobic walking ( >3 metabolic equivalents) | Non-aerobic exercise, balance, flexibility, and postural exercise | Attention, and memory |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J. Effects of Aerobic and Resistance Exercise Interventions on Cognitive and Physiologic Adaptations for Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Control Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9216. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249216

Lee J. Effects of Aerobic and Resistance Exercise Interventions on Cognitive and Physiologic Adaptations for Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Control Trials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(24):9216. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249216

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Junga. 2020. "Effects of Aerobic and Resistance Exercise Interventions on Cognitive and Physiologic Adaptations for Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Control Trials" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 24: 9216. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249216

APA StyleLee, J. (2020). Effects of Aerobic and Resistance Exercise Interventions on Cognitive and Physiologic Adaptations for Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Control Trials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9216. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249216