From Midwife-Dominated to Midwifery-Led Antenatal Care: A Meta-Ethnography

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Inclusion Criteria and Search Strategy

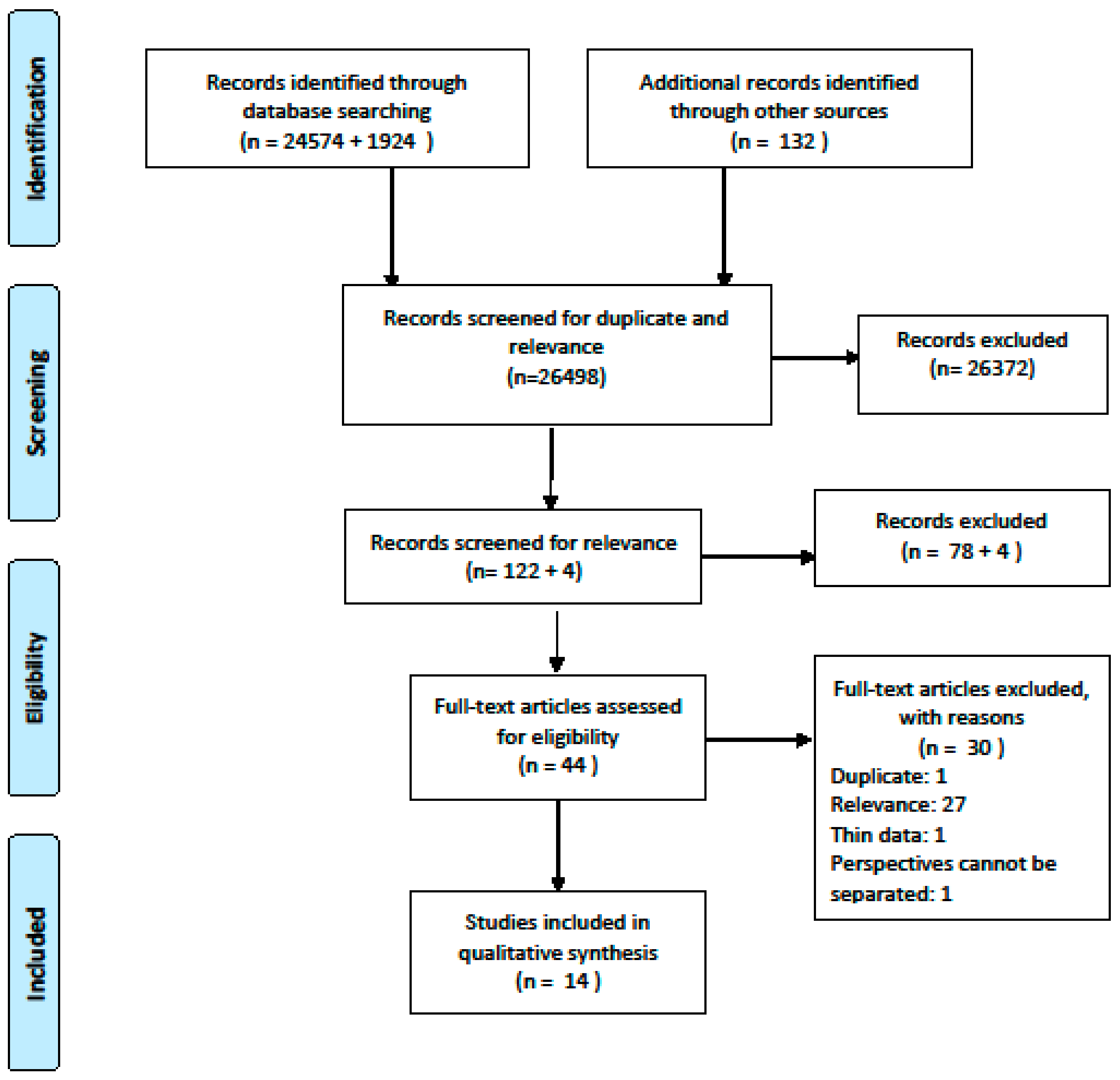

2.3. Search Outcome

2.4. Quality Appraisal

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

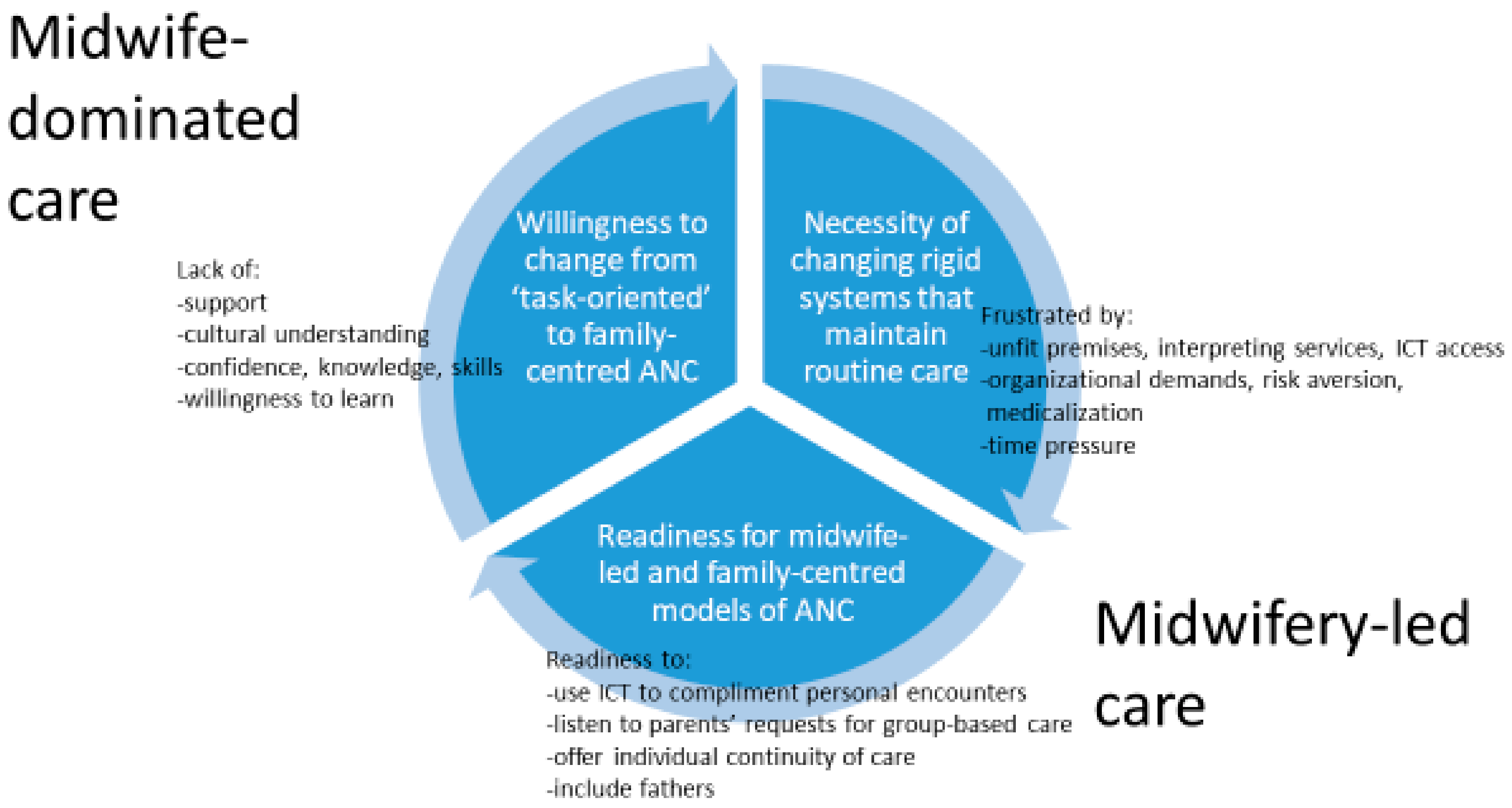

3. Results

3.1. Willingness to Change from Routine ANC to Family-Centred ANC

3.1.1. Lack of Support from Colleagues

3.1.2. Lack of Cultural Understanding

3.1.3. Lack of Confidence, Knowledge and Skills to Support New Practices

3.1.4. Lack of Willingness to Learn about and Try Group-Based Care

3.2. Necessity of Changing Rigid Systems that Maintain Routine Care

3.2.1. Frustrated by Unfit Premises, Restricted Access to ICT and Interpreting Service

3.2.2. Frustrated by Rigid Structures, Risk Aversion and Medicalization

3.2.3. Frustrated by Time Pressure and Cultural Misunderstandings

3.3. Midwives’ Readiness for Midwifery-Led and Family-Centred Models of ANC

3.3.1. Readiness to Use ICT to Complement Personal Encounters

3.3.2. Readiness to Listen to Parents’ Questions about and Requests for Group-Based Care

3.3.3. Readiness for Individual Continuity of Care

3.3.4. Readiness to Include Fathers and Family Members

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Criteria Headings | Reporting Criteria | Pages |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 Selecting meta-ethnography and getting started Introduction 1. Rationale and context for the meta-ethnography 2. Aim(s) of the meta-ethnography 3. Focus of the meta-ethnography 4. Rationale for using meta-ethnography | Describe the gap in research or knowledge to be filled by the meta-ethnography and the wider context of the meta-ethnography Describe the meta-ethnography aim(s) Describe the meta-ethnography review question(s) (or objectives) Explain why meta-ethnography was considered the most appropriate qualitative synthesis methodology | 2–3 |

| Phase 2 Deciding what is relevant Methods 5. Search strategy 6. Search processes 7. Selecting primary studies 8. Outcome of study selection | Describe the rationale for the literature search strategy Describe how the literature searching was carried out and by whom Describe the process of study screening and selection, and who was involved Describe the results of study searches and screening | 4–5 |

| Phase 3 Reading included studies Methods 9. Reading and data-extraction approach Findings 10. Presenting characteristics of included studies | Describe the reading and data-extraction method and processes Describe characteristics of the included studies | 5–7 7–11 |

| Phase 4 Determining how studies are related Methods 11. Process for determining how studies are related Findings 12. Outcome of relating studies | Describe the methods and processes for determining how the included studies are related: -Which aspects of studies were compared -How the studies were compared Describe how studies relate to each other | 11 |

| Phase 5 Translating studies into one another Methods 13. Process of translating studies Findings 14. Outcome of translation | Describe the methods of translation: -Describe steps taken to preserve the context and meaning of the relationships between concepts within and across studies -Describe how the reciprocal and refutational translations were conducted -Describe how potential alternative interpretations or explanations were considered in the translations -Describe the interpretive findings of the translation | 7,11 11–16 |

| Phase 6 Synthesizing translations Methods 15. Synthesis process Findings 16. Outcome of synthesis process | Describe the methods used to develop overarching concepts (‘synthesized translations’), and describe how potential alternative interpretations or explanations were considered in the synthesis Describe the new theory, conceptual framework, model, configuration, or interpretation of data developed from the synthesis | 11 11–12 |

| Phase 7 Expressing the synthesis Discussion 17. Summary of findings 18. Strengths, limitations and reflexivity 19. Recommendations and conclusions | Summarize the main interpretive findings of the translation and synthesis, and compare them to existing literature Reflect on and describe the strengths and limitations of the synthesis: Methodological aspects: for example, describe how the synthesis findings were influenced by the nature of the included studies and how the meta-ethnography was conducted Reflexivity—for example, the impact of the research team on the synthesis findings Describe the implications of the synthesis | 11–16 18 |

| Review Finding | Studies Contributing to the Review Finding | Assessment of Methodological Limitations | Assessment of Relevance | Assessment of Coherence | Assessment of Adequacy | Overall CERQual Assessment of Confidence | Explanation of Judgement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Will to change from routine ANC to family-centred ANC | Lack of support from colleagues Lack of cultural understanding Lack of confidence, knowledge and skills to support new practices Lack of willingness to learn and try group-based care | Andersson Ahlden Ahlden Andersson Aquino Goodwin Rominov Ahlden Andersson Dalton Sword Andersson | Minor methodological limitations. All studies but two lacked clarity about reflexivity. Two studies had minor concerns about data analysis. | Minor concerns about relevance. Nurse-midwives/midwives working at antenatal clinics in community/hospital setting in four countries. | Minor concerns regarding coherence. Data reasonably consistent within and across studies. | Minor concerns about adequacy of data. Six studies presented moderate or rich data. | Moderate confidence. | The finding was graded as moderate confidence because of minor methodological considerations, minor concerns about relevance, coherence and adequacy of data. |

| Need to change rigid systems that maintain routine care | Frustrated by unfit premises, restricted access to ICT and interpret ting service Frustrated by rigid structures, risk aversion and medicalization Frustrated by time pressure and cultural misunderstandings | Andersson Aquino Dalton Proctor Rominov Sword Ahlden Dove McCourt Wright Ahlden Aquino Browne Goodwin McCourt Whitford Wright | Minor methodological limitations. Two studies had minor concerns about data analysis. All studies but two lacked clarity about reflexivity. One study lacked clarity about ethical considerations. | Minor concerns about relevance. | Minor concerns regarding coherence. Data reasonably consistent within and across studies. | Moderate concerns about adequacy of data. Six studies presented rich data. Four studies presented moderate data, two studies presented thin data. | Moderate confidence. | The findings were graded as moderate confidence because of minor methodological limitations, minor concerns about relevance and coherence and moderate concern about data adequacy in two studies. |

| Readiness for midwife-led- and family-centred models of ANC | Readiness to use ICT to complement personal encounters Readiness to listen to parents’ questions and requests for group-based care Readiness for individual continuity of care Readiness to include fathers and family members | Dalton Rominov Andersson Ahlden Aquino Olsson Andersson Browne Dove McCourt Olsson Sword Wright Ahlden Browne Goodwin Proctor Rominov Sword | Minor methodological limitations. Two studies had minor concerns about data analysis. All studies but two lacked clarity about reflexivity. One study lacked clarity about ethical considerations. | Minor concerns about relevance. | Minor concerns regarding coherence. Data reasonably consistent within and across studies. | Minor concerns about adequacy of data. | Moderate confidence. | The findings were graded as moderate confidence because of minor methodological limitations and minor concerns about relevance and coherence. |

References

- European Board & College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. The Public Health Importance of Antenatal Care. EBCOG Position Paper on Antenatal Care. 2015. Available online: https://www.ebcog.org/post/2015/11/27/ebcog-position-paper-on-antenatal-care (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250796/9789241549912-eng.pdf;jsessionid=A91AFCD71A8DCF01C4DF0807552BC594?sequence=1 (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Downe, S.; Finlayson, K.; Tuncalp, Ö.; Gülmezoglu, A.M. Provision and Uptake of Routine Antenatal Services: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 6, CD12392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downe, S.; Finlayson, K.; Walsh, D.; Lavender, T. ‘Weighing Up and Balancing Out’: A Metasynthesis of Barriers to Antenatal Care for Marginalised Women in High-Income Countries. BJOG 2009, 116, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlayson, K.; Downe, S. Why Do Women Not Use Antenatal Services in Low- and Middle-Income Countries? A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dick-Read, G.D. Childbirth without Fear: The Principles and Practice of Natural Childbirth; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1953; ISBN 978-1780660554. [Google Scholar]

- Genest, M. Preparation for Childbirth—Evidence for Efficacy: A Review. JOGN Nurs. 1981, 10, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homer, C.S.E.; Ryan, C.; Leap, N.; Foureur, M.; Teate, A.; Catling-Paull, C.J. Group Versus Conventional Antenatal Care for Women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 11, CD007622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikberg, A.M. A Theory on Intercultural Caring in Maternity Care. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Kolip, P.; Schafers, R. A Theory of the Aims and Objectives of Midwifery Practice: A Theory Synthesis. Midwifery 2020, 84, 102653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaman, M.I.; Sword, W.; Elliott, L.; Moffatt, M.; Helewa, M.E.; Morris, H.; Gregory, P.; Tjaden, L.; Cook, C. Barriers and Facilitators Related to Use of Prenatal Care by Inner-City Women: Perceptions of Health Care Providers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, M.; Downe, S.; Bamford, N.; Edozien, L. Not-Patient and Not-Visitor: A Metasynthesis Fathers Encounters with Pregnancy, Birth and Maternity Care. Midwifery 2012, 28, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staneva, A.; Bogossian, F.; Wittkowski, A. The Experience of Psychological Distress, Depression, and Anxiety during Pregnancy: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Research. Midwifery 2015, 31, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nove, A.; Hoope-Bender, P.T.; Moyo, N.T.; Bokosi, M. The Midwifery Services Framework: What Is It, and Why Is It Needed? Midwifery 2018, 57, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Symon, A.; Pringle, J.; Cheyne, H.; Down, S.; Hundley, V.; Lee, E.; Lynn, F.; McFadden, A.; McNeill, J.; Renfrew, M.; et al. Midwifery-Led Antenatal Care Models: Mapping a Systematic Review to an Evidence-Based Quality Framework to Identify Key Components and Characteristics of Care. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidebotham, M.; Fenwick, J.; Rath, S.; Gamble, J. Midwives’ Perceptions of Their Role within the Context of Maternity Service Reform: An Appreciative Inquiry. Women Birth 2015, 28, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catling, C.J.; Reid, F.; Hunter, B. Australian Midwives’ Experiences of Their Workplace Culture. Women Birth 2017, 30, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, J.A.; Rodger, D.L.; Wilmore, M.; Skuse, A.J.; Humphreys, S.; Flabouris, M.; Clifton, V.L. “Who’s afraid?”: Attitudes of Midwives to the Use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) for Delivery of Pregnancy-Related Information. Women Birth 2014, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandall, J.; Soltani, H.; Gates, S.; Shennan, A.; Devane, D. Midwife-Led Continuity Models Versus Other Models of Care for Childbearing Women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 8, CD004667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowswell, T.; Carroli, G.; Duley, L.; Gates, S.; Gulmezoglu, A.M.; Khan-Neelofur, D.; Piaggio, G.G.P. Alternative Versus Standard Packages of Antenatal Care for Low-Risk Pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 10, CD000934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, E.F.; Ring, N.; Thomas, R.; Noyes, J.; Maxwell, M.; Jepson, R. A Methodological Systematic Review of What’s Wrong with Meta-Ethnography Reporting. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noblit, G.W.; Hare, R.D. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0803930230. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. The Interpretation of Cultures; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973; ISBN 978-0465093557. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, S.P. Sociological Explanation as Translation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1980; ISBN 978-0521297738. [Google Scholar]

- France, E.F.; Cunningham, M.; Ring, N.; Uny, I.; Duncan, E.A.S.; Jepson, R.G.; Maxwell, M.; Roberts, R.; Turley, R.L.; Booth, A.; et al. Improving Reporting of Meta-Ethnography: The eMERGe Reporting Guidance. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 1126–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist. 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Lewin, S.; Glenton, C.; Munthe-Kaas, H.; Carlsen, B.; Colvin, C.J.; Gülmezoglu, M.; Noyes, J.; Booth, A.; Garside, R.; Rashidian, A. Using Qualitative Evidence in Decision Making for Health and Social Interventions: An Approach to Assess Confidence in Findings from Qualitative Evidence Syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, A.; Moore, G.; Flemming, K.; Garside, R.; Rollins, N.; Tuncalp, O.; Noyes, J. Taking Account of Context in Systematic Reviews and Guidelines Considering a Complexity Perspective. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e000840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, E.; Christensson, K.; Hildingsson, I. Swedish Midwives’ Perspectives of Antenatal Care Focusing on Group-Based Antenatal Care. Int. J. Childbirth 2014, 4, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlden, I.; Gøransson, A.; Josefsson, A.; Alehagen, S. Parenthood Education in Swedish Antenatal Care: Perceptions of Midwives and Obstetricians in Charge. J. Perinat. Educ. 2008, 17, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, M.R.J.V.; Edge, D.; Smith, D.M. Pregnancy as an Ideal Time for Intervention to Address the Complex Needs of Black and Minority Ethnic Women: Views of British Midwives. Midwifery 2015, 31, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, L.; Hunter, B.; Jones, A. The Midwife–Woman Relationship in a South Wales Community: Experiences of Midwives and Pakistani Women in Early Pregnancy. Health Expect. 2017, 21, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rominov, H.; Giallo, R.; Pilkington, P.D.; Whelan, T. Midwives’ Perceptions and Experiences of Engaging Fathers in Perinatal Services. Women Birth 2017, 30, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sword, W.; Heaman, M.I.; Brooks, S.; Tough, S.; Janssen, P.A.; Young, D.; Kingston, D.; Helewa, M.E.; Akthar-Danesh, N.; Hutton, E. Women’s and Care Providers’ Perspectives of Quality Prenatal Care: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, S. What Determines Quality in Maternity Care? Comparing the Perceptions of Childbearing Women and Midwives. Birth 1998, 25, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, S.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Being Safe Practitioners and Safe Mothers: A Critical Ethnography of Continuity of Care Midwifery in Australia. Midwifery 2014, 30, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.; Pincombe, J.; McKellar, L. Exploring Routine Hospital Antenatal Care Consultations—An Ethnographic Study. Women Birth 2018, 31, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCourt, C. Supporting Choice and Control? Communication and Interaction between Midwives and Women at the Antenatal Booking Visit. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, J.; O’Brien, M.; Taylor, J.; Bowman, R.; Davis, D. “You’ve Got It within You”: The Political Act of Keeping a Wellness Focus in the Antenatal Time. Midwifery 2013, 30, 240–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitford, H.M.; Entwistle, V.A.; van Teijlingen, E.; Aitchison, P.E.; Davidson, T.; Humphrey, T.; Tucker, J.S. Use of a Birth Plan within Woman-Held Maternity Records: A Qualitative Study with Women and Staff in Northeast Scotland. Birth 2014, 41, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, P.; Sandman, P.-O.; Jansson, L. Antenatal “Booking” Interviews at Midwifery Clinics in Sweden: A Qualitative Analysis of Five Video-Recorded Interviews. Midwifery 1996, 12, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwelling, E.; Philips, C.R. Family-Centered Maternity Care in the New Millennium: Is It Real or Is It Imagined? J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2001, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontein-Kuipers, Y.; de Groot, R.; van Staa, A.L. Woman-Centred Care 2.0: Bringing the Concept into Focus. Eur. J. Midwifery 2018, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, D.J.; Beal, J.A.; O’Hare, C.M.; Rissmiller, P.N. Reconceptualizing the Nurse’s Role in the Newborn Period as an “Attacher”. MCN Am. J. Matern. Nurs. 2006, 31, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, A.M.; Ridgeway, J.L.; Stirn, S.; Morris, M.A.; Branda, M.E.; Inselman, J.W.; Finnie, D.M.; Baker, C.A. Increasing the Connectivity and Autonomy of RNs with Low-Risk Obstetric Patients. Am. J. Nurs. 2018, 118, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, M.K.; Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J.; Glassman, M.; Kamp Dusch, C.M.; Sullivan, J. New Parents’ Facebook Use at the Transition to Parenthood. Fam. Relat. 2012, 61, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripp, N.; Hainey, K.; Liu, A.; Poulton, A.; Peek, M.; Kim, J.; Nanan, R. An Emerging Model of Maternity Care: Smartphone, Midwife, Doctor? Women Birth 2014, 27, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodward, V. Caring for Women: The Potential Contribution of Formal Theory to Midwifery Practice. Midwifery 2000, 16, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE Antenatal Care for Uncomplicated Pregnancies. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg62/chapter/Woman-centred-care (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- International Confederation of Midwives. Core document: Philosophy and Model of Midwifery Care. Available online: https://www.internationalmidwives.org/assets/files/definitions-files/2018/06/eng-philosophy-and-model-of-midwifery-care.pdf#:~:text=ICM%20Philosophy%20of%20Midwifery%20Care%20%E2%80%A2%20Pregnancy%20and,most%20appropriate%20care%20providers%20to%20attend%20childbearing%20women (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Carolan, M.; Hodnett, E. ‘With woman’ philosophy: Examining the evidence, answering the questions. Nurs. Inq. 2007, 14, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aanensen, E.H.; Skjoldal, K.; Sommerseth, E.; Dahl, B. Easy to Believe In, But Hard to Carry Out—Norwegian Midwives’ Experiences of Promoting Normal Birth in an Obstetric-Led Maternity Unit. Int. J. Childbirth 2018, 8, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leap, N.; Edwards, N. The Politics of Involving Women in Decisions about Their Care. In The New Midwifery: Science and Sensitivity in Practice, 2nd ed.; Page, L., Mc Candlish, R., Eds.; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0443100024. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K. Qualitative Research: Standards, Challenges and Guidelines. Lancet 2001, 358, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Getting started—identifying the topic of the study and defining the aim |

| 2 | Deciding what is relevant to the initial interest—including relevant studies, describing search strategy and criteria for inclusion and exclusion |

| 3 | Reading the studies—noting studies’ interpretative metaphors through repeated readings |

| 4 | Determining how the studies are related—determining the relationship between the studies by creating a list of key metaphors (themes, concepts, phrases, ideas) and assessing whether the relationships are reciprocal (i.e., findings across studies are comparable), refutational (findings stand in opposition to each other) or represent a line of argument |

| 5 | Translating the studies into one another—comparing metaphors and their interactions within single studies and across studies, and at the same time protecting uniqueness and holism |

| 6 | Synthesizing translations—creating a new whole from the sum of the parts, enabling a second-level analysis |

| 7 | Expressing the synthesis—finding the appropriate form for the synthesis to be effectively communicated to the audience |

| Study | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alden et al., (2008) | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | Y- | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Andersson et al., (2014) | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | Y- | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Aquino et al., (2015) | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | Y- | YY | Y- | YY | YY |

| Browne et al., (2014) | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -- | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Dalton et al., (2014) | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -- | Y- | Y- | Y- | YY |

| Dove et al., (2014) | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | Y- | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Goodwin et al., (2018) | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -- | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| McCourt (2006) | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -- | -- | YY | YY | YY |

| Olsson et al., (1996) | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | Y- | Y- | YY | YY | YY |

| Proctor (1998) | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -- | -Y | YY | YY | YY |

| Rominov et al., (2017) | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Sword et al., (2012) | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Whitford et al., (2014) | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -- | YY | YY | YY | YY |

| Wright et al., (2018) | YY | YY | YY | YY | YY | -Y | YY | -Y | YY | YY |

| Author (Year) Country | Aim | Sample & Setting | Methodology | Methods for Data Collection & Analysis | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahlden et al., (2008) Sweden | To describe perceptions of parenthood education among midwives and obstetricians in charge of antenatal care. | Midwives (n = 13) Obstetricians (n = 12) Large and small ANC clinics: Rural and urban areas, geographical distribution in Sweden, and annual ANC meeting | Qualitative phenomeno graphic approach | Focus group interviews | Support in transition to parenthood was important. Parenthood education should focus on awareness of the expected child, confidence in the biological processes and the change of roles. |

| Andersson et al., (2014) Sweden | To investigate and describe antenatal midwives’ perceptions and experiences of their current work, focusing on their opinions about group-based antenatal care. | Midwives (n = 56) Antenatal clinics all over Sweden | Mixed methods | Interviews with closed questions and comments Descriptive statistics and content analysis | Midwives were satisfied with their work, but had reservations concerning time constraints and parental classes. Many expressed interest in group-based care, but expressed personal and organizational obstacles to implementing the model. |

| Aquino et al., (2015) UK | To explore midwives’ experiences of providing care for Black and minority ethnic women. | Midwives (n = 20) NHS Antenatal clinics in North West England | Qualitative design | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis | Midwives found it difficult to communicate with women whose English was limited. They described a mismatch between midwives’ and women’s expectations of care and highlighted the necessity of inter-agency collaboration to address holistic care. |

| Browne et al., (2014) Australia | To explore midwives’ communication techniques intended to promote a wellness focus in the antenatal period. | Midwives (n = 14) Hospital/community settings in two states, including high-risk | Qualitative design | Focus group interviews | Midwives used health-promoting strategies in their work as an effort to reduce women’s anxiety and promote wellness-focused care. |

| Dalton et al., (2014) Australia | To investigate midwives’ attitudes toward and experiences of ICT use to identify potential causal factors that encourage or inhibit their usage in ANC. | Midwives (n = 19) Antenatal education in a metropolitan hospital | Semi-structured interviews, focus group interviews and survey Thematic and statistical analyses | Midwives recognized potential benefits of ICT use to deliver pregnancy-related health information, but had reservations about their use in everyday work. | |

| Dove & Muir-Cochrane (2014) Australia | To examine how midwives and women within a continuity of care midwifery programme conceptualized childbirth risk and the influences of these conceptuali zations on women’s choices and midwives’ practice. | Midwives (n = 8) Obstetrician (n = 1) Women (n = 17) Community-based continuity of midwifery care programme | Critical ethnography | Semi-structured interviews and observation | Midwives assumed a risk-negotiator role in order to mediate relationships between women and hospital-based maternity staff. This role relied on the trust engendered by their relationship with the women. |

| Goodwin et al., (2018) UK | To explore the relationship between first-generation migrant women and midwives focusing on factors contributing to these relationships and their effect on the caring experience. | Midwives (n = 11) Pakistani women (n = 9) Community-based antenatal clinics | Focused ethnography | Semi-structured interviews Observation Thematic data analysis | The midwife–woman relationship was important for participants’ experiences of care. Social and ecological factors influenced the relationship, and marked differences were identified between midwives and women in their perceived importance of these factors. |

| McCourt (2006) UK | To explore the nature of information giving, choice and communication with pregnant women, in both conventional and caseload midwifery care. | Booking visits with pregnant women (n = 40) and midwives (n = 40) Hospital clinic GP clinic Women’s homes | Qualitative design | Non- participant observation Structured and qualitative analysis | Interactional patterns differed according to model and setting of care. A continuum of styles of communication were identified, and were more formal in conventional care than in caseload midwifery care. |

| Olsson et al., (1996) Sweden | To describe antenatal ‘booking’ interviews regarding content and to illuminate the meaning of the ways midwives and expectant parents relate to each other. | Booking visits with midwives (n = 5), women (n = 5) and fathers (n = 2) Midwifery clinics at five urban and rural primary care health centres | Qualitative design | Video-recorded booking interviews Content analysis and phenomeno logical hermeneutic analysis | Two perspectives of antenatal midwifery care, obstetric and parental, operated alternately and in competition within the interviews. |

| Proctor (1998) UK | To identify and compare the perceptions of women and midwives concerning women’s beliefs about what constitutes quality in maternity services. | Midwives (n = 47) Women (n = 33) Two large maternity units | Qualitative design | Focus group interviews Thematic analysis | An understanding of the concerns of women by maternity care staff is important in the development of a woman-centred service. |

| Rominov et al., (2017) Australia | To describe midwives, perceptions and experiences of engaging fathers in perinatal services. | Midwives (n = 106) Practising midwives (public and private) | Multi-method approach | Semi-structured interviews (n = 13) Descriptive analysis andsemantic thematic analysis | Midwives unanimously agreed that engaging fathers is part of their role and acknowledged the importance of receiving education to develop knowledge and skills with regard to fathers. |

| Sword et al., (2012) Canada | To explore women’s and care providers’ perspectives of quality prenatal care to inform the development of items for a new instrument. | Prenatal care providers (n = 40) Pregnant women (n = 40) Five urban centres across Canada | Qualitative descriptive approach | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis | A recurrent theme woven throughout the data reflected the importance of a meaningful relationship between a woman and her prenatal care provider that was characterized by trust. |

| Whitford et al., (2014) UK | To consider the use of a standard birth plan section within a national, woman-held maternity record. | Women (n = 42) Midwives (n = 15) Obstetricians (n = 6) GPs (n = 3) Antenatal clinics | Exploratory qualitative and longitudinal study | Interviews Thematic analysis | Staff and women were generally positive about the provision of a birth plan. Staff recognized the need to support women in completing their birth plan, but noted practical challenges concerning this. |

| Wright et al., (2018) Australia | To reveal how midwives enact woman-centred care in practice. | Midwives (n = 16) Public antenatal clinics and antenatal consultations | Contempo rary focused ethnography | Interviews and observation Thematic analysis | The ways in which midwives interacted with women during routine antenatal care demonstrated that some practices in a hospital setting can either support or undermine a woman-centred philosophy. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dahl, B.; Heinonen, K.; Bondas, T.E. From Midwife-Dominated to Midwifery-Led Antenatal Care: A Meta-Ethnography. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238946

Dahl B, Heinonen K, Bondas TE. From Midwife-Dominated to Midwifery-Led Antenatal Care: A Meta-Ethnography. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(23):8946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238946

Chicago/Turabian StyleDahl, Bente, Kristiina Heinonen, and Terese Elisabet Bondas. 2020. "From Midwife-Dominated to Midwifery-Led Antenatal Care: A Meta-Ethnography" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 23: 8946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238946

APA StyleDahl, B., Heinonen, K., & Bondas, T. E. (2020). From Midwife-Dominated to Midwifery-Led Antenatal Care: A Meta-Ethnography. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238946