Specialised Teachers’ Perceptions on the Management of Aggressive Behaviours in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Development of Interview Questions

2.3.2. Interview Process

2.3.3. Focus Group Transcription

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Measures to Ensure Reliability

2.6. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

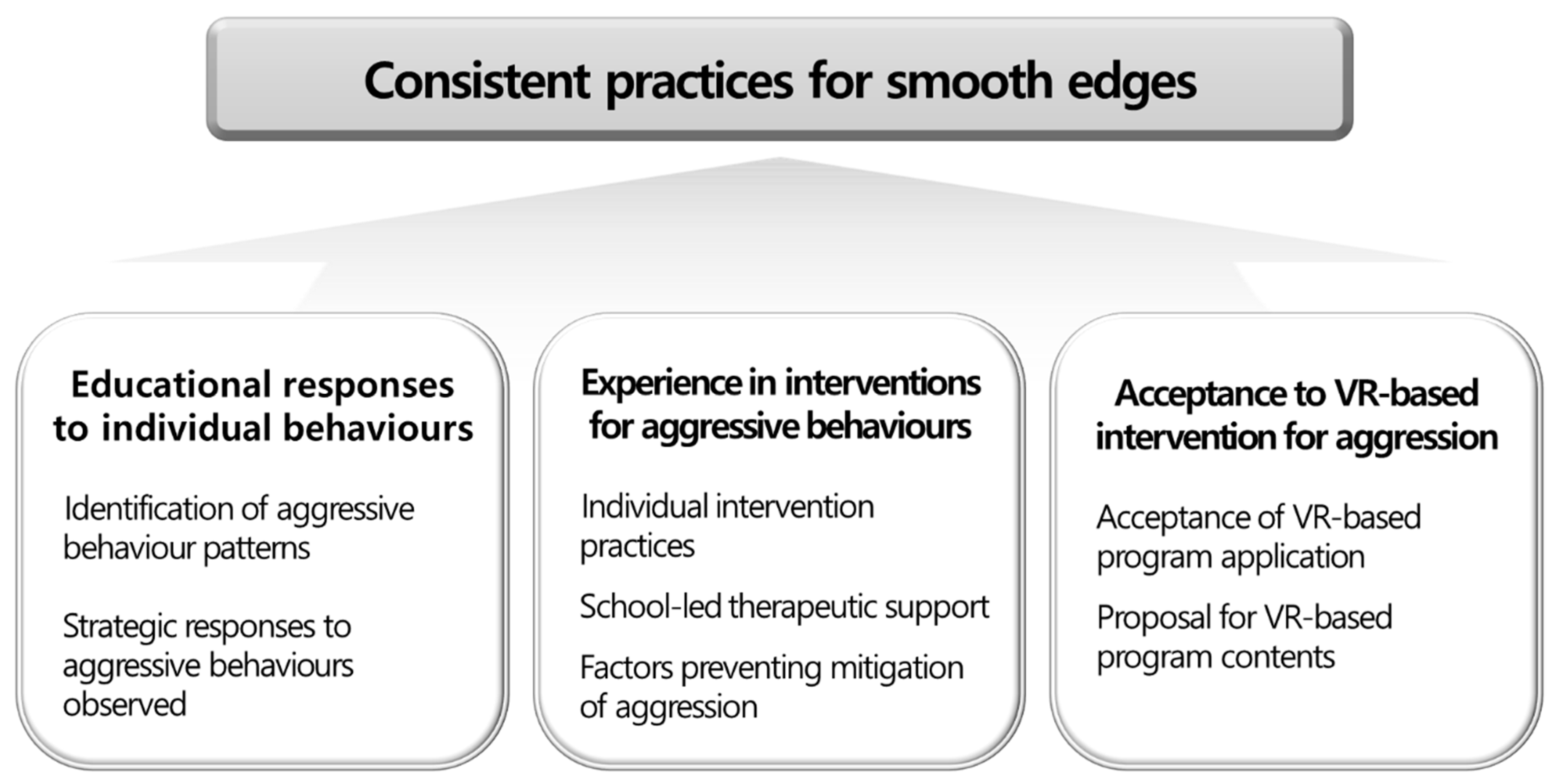

3.1. Core Theme: “Consistent Practices to Smooth Edges”

“The aggressive behaviors displayed by primary school students with ASD are not serious or destructive; nonetheless their aggression needs to be addressed and controlled to prevent its progressive increase over time.”(Focus Group 1; Primary school group)

“When I forced them to do something in terms of adjusting their behaviors, their explosive behavior remained unchanged.”

“Understanding and helping them to build trust with me seems to be rather more important, along with a consistent approach.”(Focus Group 2; Middle school group)

3.2. Categories: Educational Responses to Individual Behaviors

3.2.1. Identification of Aggressive Behavior Patterns

“There was a child who kept picking off a scab from a neck wound, delaying healing, and later tried to find a scab on someone else’s body to pick it off. This kind of behavior can take place without any malice.”(Focus Group 1; Elementary School Group)

“Scratching, pinching, screaming, and running out; it’s really diverse.”(Focus Group 1; Primary school group)

“Some children exhibit their aggression even when there is something they want to eat more of, or when they do not want to eat something their teacher recommends.”(Focus Group 1; Primary school group)

“In general, children with low levels of verbal communication skills tend to be more aggressive. Their inability to express themselves clearly tends to trigger aggressive behavior.”(Focus Group 3; High school group)

“One student who has some problems with speaking reacts sensitively to external stimuli (e.g., accidental touch) by yelling and crying, and their aggression gets worse. The student knows that such a reaction is more effective in drawing the teachers’ attention.”(Focus Group 1; Primary school group)

3.2.2. Strategic Responses to Aggressive Behaviors Observed

“I let the student concerned take a break for 10 to 15 min in the comfort room or an empty classroom nearby without using physical restraint. I try to help the student calm down by turning off the light, playing music, or putting cushions, which are available in the comfort room. If secluding the student in a separate space is not possible, I let all the other students leave the classroom to enable the student to stay alone.”(Focus Group 3; High school group)

“I keep talking with the student to help them understand what’s happening around them and eventually to prevent aggression. I am repeatedly talking to nonverbal children.”(Focus Group 1; Primary school group)

“Rapport building with teachers is important for them. I try to find the best way to effectively help children become stable is through continuous interactions. We sometimes count while breathing at the same pace, and I arrange activities that the student likes for specific days on which their aggression is predicted based on their behavioral history.(Focus Group 2; Middle school group)

“As a teacher at a special education school, I have received training and learned martial arts; I am a belt holder.”(Focus Group 3; High school group)

“The student concerned is instructed to practice certain activities as an alternative to aggressive behaviors from the beginning of the semester, and tell them if you get an urge to take an action, clap hard and show it to me; this is my way of encouraging alternative behaviors.”(Focus Group 2; Middle school group)

3.3. Categories: Experience in Interventions for Aggressive Behaviors

3.3.1. Individual Intervention Practices

“I encourage the student concerned to move a lot. Active activities such as walking around the school will make them feel better and help them stay out of trouble.”(Focus Group 1; Primary school group)

“I sometimes encourage the student concerned to bring a sandbag to the school upon consent from their parents and we go hiking together to the mountain behind the school.”(Focus Group 2; Middle school group)

“We highly recommend drug treatment. Parents want to see that their children do not need to take medicine. Indeed, there are side effects such as drowsiness and lethargy when drug treatment is used. I hope that specialized teachers can take part in the decision-making process for drug treatment.”(Focus Group 3; High school group)

3.3.2. School-Led Therapeutic Support

“There is no aggression management manual/guidelines prepared at school level. If there is any problem caused by a student with ASD in an inclusive classroom, the respective teacher calls me to pick up the student without any attempt to settle down the situation; they have no interest in the rationale for inclusive classroom.”(Focus Group 2; Middle school group)

“There was a child who kept hitting their head on the bus, and a teaching assistant was assigned to the student to assist with their arrival at and departure from the school after the meeting with school representatives, parents, and other related personnel.”(Focus Group 1; Primary school group)

3.3.3. Factors Preventing Mitigation of Aggression

“Mitigation strategies would become less effective if family members and schools fail to demonstrate consistent educational approaches.”(Focus Group 1; Primary school group)

“Selfish parenting style has a negative impact on aggression mitigation.”(Focus Group 2; Middle school group)

3.4. Broader Theme: Acceptance to VR-Based Intervention Model for Aggression

3.4.1. Acceptance of VR-Based Program Application

“I think VR-based interventions would be a solution to overcome physical constraints felt in a school, and it would also help the students who keep breaking things because they will be satisfied by replicating such actions in a virtual space.”(Focus Group 2; Middle school group)

“To watch VR-based programs, a device is required; nonetheless, it can be denied by some students.”(Focus Group 1; Primary school group)

3.4.2. Proposal for VR-Based Program Contents

“They need something that enables them to express anger and relieve stress. Something like a heavy sandbag hung vertically so that they can hit it when they feel angry.”(Focus Group 3; High school group)

“VR experiences in a variety of episodes involving aggressive behaviors can be a good practice; it is like a rehearsal for real-life situations involving the students themselves, and such situations can be reduced or prevented following VR experiences.”(Focus Group 2; Middle school group)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, C.; Cook, E.H.; Leventhal, B.L.; Amaral, D.G. Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neuron 2000, 28, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresham, F.M.; Sugai, G.; Horner, R.H. Interpreting Outcomes of Social Skills Training for Students with High-Incidence Disabilities. Except. Child. 2001, 67, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, D.R. Social and Personality Development, 6th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Frith, U. Autism: Explaining the Enigma, 2nd ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McClintock, K.; Hall, S.; Oliver, C. Risk markers associated with challenging behaviours in people with intellectual disabilities: A meta-analytic study. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2003, 47, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, J.; Viding, E.; Blair, R.J.; Frith, U.; Happé, F. Autism spectrum disorder and psychopathy: Shared cognitive underpinnings or double hit? Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 1789–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabio, R.A.; Caprì, T. Complex cognitive processes and aggression. Ric. Psicol. 2020, 44, 713–746. [Google Scholar]

- National Standards Project. National Professional Development Center on ASD/2011. Available online: https://www.nationalautismcenter.org/national-standards-project/ (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorder. Available online: https://autismpdc.fpg.unc.edu/assessment (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Odom, S.L.; Boyd, B.A.; Hall, L.J.; Hume, K. Evaluation of comprehensive treatment models for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2010, 31, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Odom, S.L.; Hume, K.A.; Cox, A.W.; Fettig, A.; Kucharczyk, S.; Brock, M.E.; Plavnick, J.B.; Fleury, V.P.; Schultz, T.R. Evidence-Based Practices for Children, Youth, and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Comprehensive Review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 1951–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, S.J.; Dawson, G. Early Start Denver Model for Young Children with Autism: Promoting Language, Learning, and Engagement; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Strain, P.S.; Hoyson, M. The Need for Longitudinal, Intensive Social Skill Intervention. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2000, 20, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortman, D. Are Educators Prepared to Teach Students with Autism? Master’s Thesis, Ohio University, Athens, OH, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barned, N.E.; Knapp, N.F.; Neuharth-Pritchett, S. Knowledge and Attitudes of Early Childhood Preservice Teachers Regarding the Inclusion of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Early Child. Teach. Educ. 2011, 32, 302–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Ye, J. Exploring the social competence of students with autism spectrum conditions in a collaborative virtual learning environment—The pilot study. Comput. Educ. 2010, 54, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.J.; Ginger, E.J.; Wright, K.; Wright, M.A.; Taylor, J.L.; Humm, L.B.; Olsen, D.E.; Bell, M.D.; Fleming, M.F. Virtual Reality Job Interview Training in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 2450–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Chiang, H.-C.; Ye, J.; Cheng, L.-H. Enhancing empathy instruction using a collaborative virtual learning environment for children with autistic spectrum conditions. Comput. Educ. 2010, 55, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruegar, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt, T.A. The SAGE Dictionary of Qualitative Inquiry, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Prizant, B.M.; Wetherby, A.M.; Rubin, E.M.S.; Laurent, A.C.; Rydell, P.J. The Scerts Model: A Comprehensive Educational Approach for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders; Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2005; Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal, A. Aggressive Behaviors in Students with Autism: A Review of Behavioral Interventions. Culminating Proj. Spec. Educ. 2016, 9, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Duff, S.V.; Shumway-Cook, A.; Woollacott, M. Clinical management of the patient with reach, grasp, and manipulation disorders. In Motor Control: Translating Research into Clinical Practice, 3rd ed.; Shumway-Cook, A., Wollacott, M., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014; pp. 552–593. [Google Scholar]

- Dingfelder, H.E.; Mandell, D.S. Bridging the Research-to-Practice Gap in Autism Intervention: An Application of Diffusion of Innovation Theory. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2011, 41, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacca, J.; Baldiris, S.; Fabregat, R.; Graf, S.; Kinshuk. Augmented reality trends in education: A systematic review of research and applications. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2014, 17, 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Radu, I. Augmented reality in education: A meta-review and cross-media analysis. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2014, 18, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capri, T.; Nucita, A.; Iannizzotto, G.; Stasolla, F.; Romano, A.; Semino, M.; Giannatiempo, S.; Canegallo, V.; Fabio, R.A. Telerehabilitation for Improving Adaptive Skills of Children and Young Adults with Multiple Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | ID (N = 13) | Teaching Experience | Gender | Affiliation Address | General or Special Education School | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yr | Mean ± SD | Name of City (Province) | N (%) | Type | N (%) | |||

| Group 1 (Primary school teacher) | Participant A | 17 | 9.27 ± 4.94 | F | Seoul | Gyeonggi province 6 (46.15%) Incheon 1 (7.70%) Seoul 6 (46.15%) | General | General 10 (76.92%) Special 3 (23.08%) |

| Participant B | 4 | F | Seoul | Special | ||||

| Participant C | 7 | F | Gyeonggi province | Special | ||||

| Participant D | 12 | F | Gyeonggi province | General | ||||

| Group 2 (Middle school teacher) | Participant E | 1 | F | Gyeonggi province | General | |||

| Participant F | 10 | F | Seoul | General | ||||

| Participant G | 11 | F | Gyeonggi province | General | ||||

| Participant H | 13 | F | Gyeonggi province | General | ||||

| Group 3 (High school teacher) | Participant I | 5 | F | Incheon | General | |||

| Participant J | 2.5 | F | Gyeonggi province | General | ||||

| Participant K | 15 | F | Seoul | General | ||||

| Participant L | 11 | F | Seoul | General | ||||

| Participant M | 12 | F | Seoul | Special | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jung, M.; Lee, E. Specialised Teachers’ Perceptions on the Management of Aggressive Behaviours in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8775. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238775

Jung M, Lee E. Specialised Teachers’ Perceptions on the Management of Aggressive Behaviours in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(23):8775. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238775

Chicago/Turabian StyleJung, Miran, and Eunmi Lee. 2020. "Specialised Teachers’ Perceptions on the Management of Aggressive Behaviours in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 23: 8775. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238775

APA StyleJung, M., & Lee, E. (2020). Specialised Teachers’ Perceptions on the Management of Aggressive Behaviours in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8775. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238775