1. Introduction

Over the past 40 years, China’s urbanization and industrialization have progressed rapidly. Simultaneously, this intensive economic development has caused serious environmental pollution. Water and air pollution in particular have seriously affected people’s quality of life and the rephrasing of sustainable regional development [

1]. Based on the negative impacts of pollution on the physical and mental health of residents, scientists have listed the main components of air pollution, including solid particulate matter (PM) and sulfur dioxide (SO

2), as the main targets for monitoring and controlling air pollution. According to the World Bank’s (2007) report, Cost of Pollution in China: Economic Estimates of Physical Damages, the damage caused by air and water pollution in China was equivalent to 5.8% of its real GDP [

2]. This finding indicates that environmental pollution is a typical manifestation of negative externalities in the production process: the private marginal costs of discharging environmental pollutants are lower than the social marginal costs.

Previous literature documented that government fiscal expenditure plays a key role in environmental quality. For instance, López et al. (2011) provided a theoretical model for how both the amount and composition of government spending affected environmental pollution [

3]. In line with this stream of research, Hua et al. (2018) documented that the public education spending had a negative relationship with SO

2 emission [

4]. Lin et al. (2019) maintained that fiscal spending promoted green economic growth through spending on both education and R&D [

5]. However, the effects of fiscal expenditures on science and technology (FESTs) on environmental pollution have received little attention. This paper fills this gap.

López et al. (2011) modeled and measured the following four mechanisms about fiscal spending patterns on the environment [

3]. First, high economic growth increased environmental pressure, and this causation is known as the scale effect. Second, human capital-intensive productions tended to pollute less than physical capital-intensive productions, which is called the composition effect. Third, investment in R&D and the diffusion of knowledge may have reduced the pollution–output ratio by improving efficiency and developing cleaner technologies, and this reduction was a result of the technique effect. Fourth, the increase in income had a positive impact on environmental quality, which is called the income effect. In this study, we investigate the effect of FESTs on environmental pollutants. In other words, we identify and analyze the technique effect.

We studied the relationship between FESTs and environmental pollution in China for the following reasons. Firstly, China is facing concerns about environmental pollution control. According to the Air Pollution Prevention Action Plan issued by the State Council in 2017, the concentration of inhalable particulate matter in cities at the prefecture or higher level should be reduced by more than 10% from the levels in 2012. The concentration of fine particulate matter in the Jing-Jin-Ji region [

6], Yangtze River Delta, and Pearl River Delta should be decreased by 25%, 20%, and 15%, respectively.

Secondly, the market failure of environmental pollution provides theoretical justification for governmental intervention in environmental issues [

7]. In China, most of the environmental managements are delegated to local governments [

8]. Because local governments play a positive role in economic development and the coordination of social orders, they are of great importance in the implementation of environmental policies and governance. More important, China’s current Laws of Environmental Protection and Laws of the Prevention and Control of Air Pollution require local governments to take responsibility for the air quality of their regions, thus leading these governments to increase investment in the prevention and control of air pollution. Consequently, it is necessary to study the relationships between FESTs and environmental pollution.

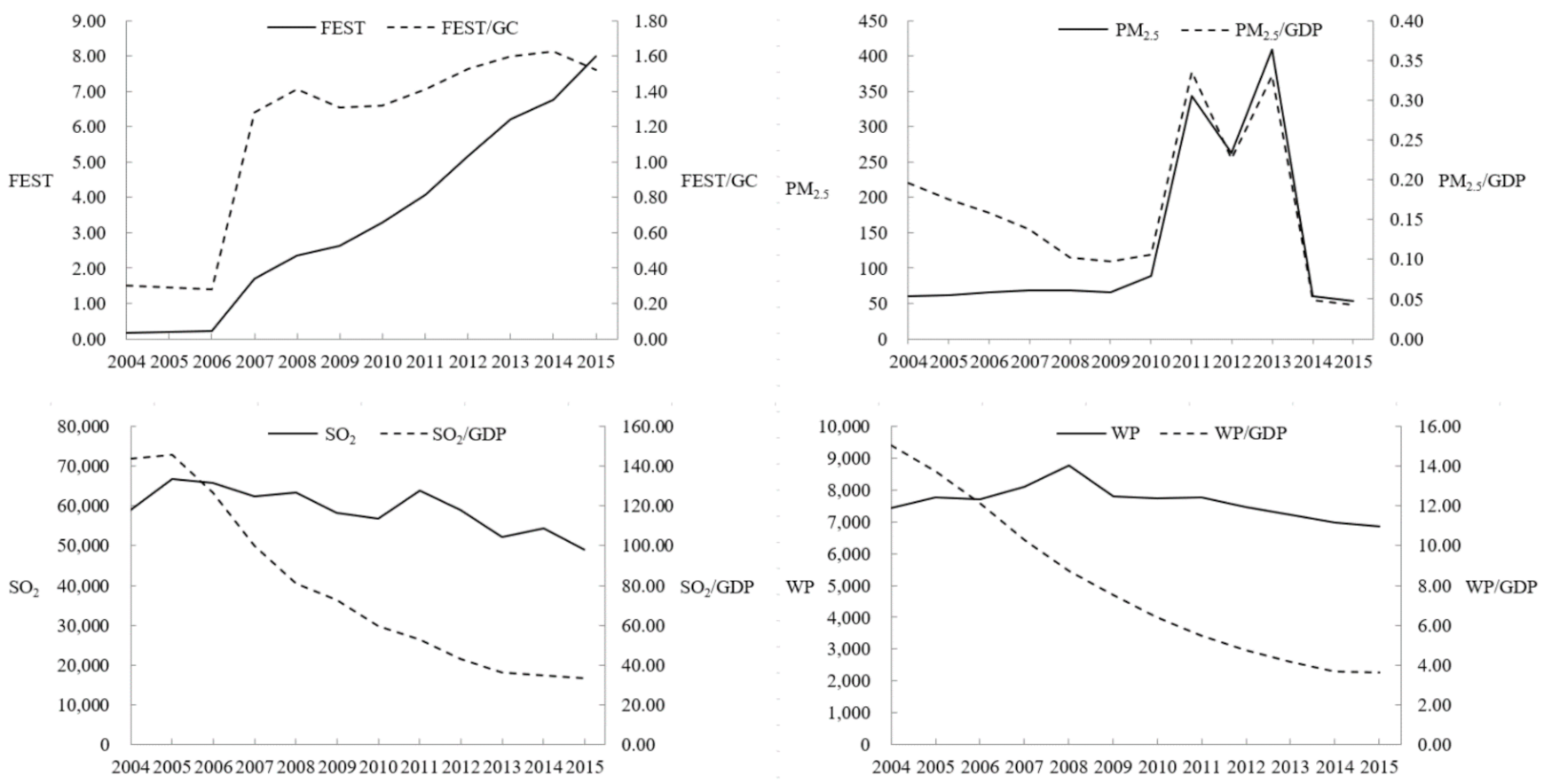

We used prefecture-level panel data to assess how FESTs affected the concentration of SO

2 commission, wastewater, and atmospheric particulate matter of less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter (PM

2.5) in China from 2004 to 2015. These three pollutants are criteria pollutants, ensuring that we accessed the maximum number of standardized and consistent observations. We showed that more FESTs significantly reduced SO

2 emissions, which is consistent with the findings of López et al. (2015) and Hua et al. (2018) [

4,

9], but fail to significantly alleviate PM

2.5 and polluted water emission. Moreover, we used government R&D investments and fixed asset investments as mechanism variables to test the channels. We found that FESTs could promote R&D expenditures and impede fixed asset investments, which together could lead to a mitigation of total pollution.

An endogeneity problem arises, because it is difficult to disentangle whether serious environmental pollution leads to more FESTs or vice versa. However, Hua et al. (2018) argued that reverse causation seems improbable to bias our estimates since pollution emission of a certain year is unlikely to affect fiscal spending of the same year. The National People’s Congress and the Ministry of Finance predetermine and approve the governmental fiscal budget. FESTs can hardly be changed. Thus, FESTs can remain a major endogenous factor due to the omitted variable problem. Another possible cause of estimation bias may be the imprecision in calculation of China’s macroeconomic aggregates. The aggregation of measurement error in macroeconomics, especially in developing and transitional countries, is a well-known problem in empirical literature [

10].

Following recent Hua et al. (2018) and Lin et al. (2019) [

4,

5], we employed an instrumental variable method and the generalized method of moments (GMM) to overcome potential endogeneity. Furthermore, we found that the effects of FESTs on reducing environmental pollution varied across regions and times, mainly due to their varying emphases on environmental pollution at different stages of economic development.

We contribute to the existing literature in two of the following ways, from theoretical and empirical aspects. Firstly, we add to the growing body of literature that analyzes the relationship between government expenditure and environmental pollution. Prior studies analyze government spending composition [

3] and public education spending [

4]. However, little attention has been paid to the FESTs, which is a mandatory item in the fiscal budget. Our study differs from prior researches because we focus on three kinds of underlying mechanisms including R&D, fixed asset investment and environmental pollution intensity and use micro-level city data to explore the impact of FESTs on environmental pollution. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to examine the impact of FESTs on various environmental pollutants.

Secondly, we constructed a theoretical model to study the FESTs-environmental pollution relationship. In addition, the effect of FESTs on environmental pollution is greatly heterogenous across environmental pollution in different areas. Thus, our study provides additional insight into the existing literature, and suggests that local governments should invest more on FESTs to reduce environmental pollution.

Thirdly, this study enhances our understanding of the factors on environmental costs and ecological benefits. We found that FESTs could reduce SO2 emissions and PM2.5 concentrations, but fail to significantly alleviate polluted water emission. FESTs can play a role in guiding funds because they help to attract more external private investment, thereby contributing to the optimization of technical structure. In addition, our analysis of the impact of FESTs should be of interest to governments and regulators who are concerned with environmental pollutant and economic development.

The rest of our paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we provide a literature review and develop the hypotheses. In

Section 3, we discuss the data, variables, and econometric specifications. In

Section 4, we present the baseline estimation results. In

Section 5, we give a series of robustness checks, and in

Section 6, we conclude the paper.

2. Literature Review and Developed Hypotheses

A strand of literature explores the relationship between the fiscal expenditure and environmental pollution. For instance, Jiang, et al. [

11] adopted a spatial econometric model to study the direct and indirect spillover effects on provincial governments on SO

2 emissions in China. They found that there existed an inverted U-shaped curve and expenditure for environmental protection was negatively correlated with SO

2 pollution. Wang and Li [

12] investigated the effect of financial expenditure on carbon emission by using provincial-level dynamic panel from 1996 to 2010. Their results showed that the scale of financial expenditure increased per capita carbon emissions, whereas the composition of financial expenditure reduced per capital carbon emissions.

Another strand of literatures examined the impact of fiscal policy on environmental pollution. For example, Cheng

, et al. [

13] evaluated the effect of fiscal decentralization on CO

2 emissions in China by using a dynamic panel regression model during the 1997–2015 sample period. Their results showed that the effect of fiscal decentralization on CO

2 emissions was nonlinear, and per capita fiscal expenditure amplified the negative relationship between fiscal decentralization and CO

2 emissions. Consistent with Cheng, Fan, Chen, Meng, Liu, Song and Yang [

13], Hao

, et al. [

14] also documented the inverted-U shaped relationship between fiscal decentralization and GDP per capita. However, these researches mostly studied the fiscal policy and the total financial expenditure on environmental pollution. Studies on FESTs on environmental pollution are rare. We have filled this gap. According to our knowledge, we are the first to study the effect of FESTs on environmental pollution.

Numerous empirical studies have shown that fiscal spending is a significant determinant of environmental pollution [

3,

4,

9,

15,

16,

17]. For instance, Halkos and Paizanos (2013) used data from 77 countries to examine the impacts of government spending on environmental pollution [

16]. They found that government spending had a negative and direct impact on SO

2 emissions, while the direct effect on carbon dioxide pollution was negligible. López et al. (2011), emphasized the importance of government spending structure [

3]. Their study suggested that spending structures focused on public services were conducive to reducing pollution, while increasing government spending had no effect on environmental quality unless the structure of expenditure was changed. López and Islam (2015) studied the effects of federal and state government expenditures on important air pollutants in the United States [

9]. Their results showed that state and central governments that redistributed spending on private goods to social and public goods could reduce air pollution concentration, while changes to the composition of federal spending had no effects on air pollution concentration.

According to the literature, the direction of the impact of fiscal expenditure on environmental pollutants is uncertain. This direction is influenced by factors such as the external characteristics of pollutants [

18], the scale and structure of fiscal expenditure [

19], and the efficiency of expenditure [

16]. Therefore, governments cannot simply rely on increasing the scale of fiscal expenditures to reduce environmental pollution [

3]. Instead, the government should identify expenditure items that are conducive to mitigating environmental protection in each classified project to reduce pollutant emissions based on the specific conditions of their own environmental pollution.

Generally, FESTs include investments in the green economy and introduce advanced emission reduction technologies, which are effective ways to reduce pollution emissions [

5]. As discussed earlier about the technique effect mechanism, FESTs can accelerate the adjustment of the production factor structure through green production technology and R&D investment [

4,

20], and create a good external environment for enterprise-level technological innovation and thus reduce environmental pollution [

16]. López et al. (2011) reported that a 10% increase in the share of public expenditure may result in a 4% reduction in SO

2 concentration and a 7% decrease in lead concentration [

8]. Hua et al. (2018) used city-level data to estimate the composition effect and the technique effect of education spending and R&D spending in China and found that the former seemed to be slightly stronger than the latter [

4]. Clearly, the adjustment of the public expenditure structure can be an effective supplement to a government’s environmental regulations. In addition, we construct a theory model to document the relationship between FESTs and environmental pollution in

Appendix A. In this vein, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). The effect of FESTs on environmental pollution is negative.

Previous empirical literature has shown mixed results of how fiscal expenditures affect pollution. Traditional macroeconomic theory suggests that an increase in government spending would improve the economic operating environment and promote economic growth [

21]. However, with the deepening of theoretical research, the negative correlation between government scale and economic growth has also attracted widespread attention. The expansion of government expenditure increases taxes. Taxes crowd out private-sector investments and consumptions. Therefore, government expenditures negatively affect economic developments [

22].

The analysis of indirect effects also requires the determination of the shape of the environmental Kuznets curve. Many scholars claim that there is an inverse U-shaped relationship between environmental pollution and per capita real income [

18,

23]. Specifically, when economic development reaches a certain level, environmental pollution will be curbed by more investments in environmental protection or transformations of low-end polluting industries [

24]. Yu and Chen (2010) investigated China’s provincial panel data and find that the expansion of government spending significantly influenced energy intensity since the Asian financial crisis [

25,

26]. The positive impact of government spending has remained significant since the changes in China’s economic conditions.

In general, FESTs guide the adjustment of the production-factor structure by accumulating human capital and providing a good external environment for enterprises to control pollution through technological innovation [

4,

26,

27]. For instance, Lin and Zhu (2019) documented that education spending and R&D spending promoted green economic growth through human-capital intensive activities and technological activities [

5], which is consistent with the results of Hua et al. (2018) [

4].

Increasing the proportion of investment in clean technology and introducing advanced emission reduction technologies are effective ways to reduce pollution emissions [

28]. Levinson (2015) documented the existence of technique effect by revealing the improvement value of US manufacturing output and reducing pollution [

20]. Sandberg, et al. (2019) maintained that spending more on R&D and innovation could promote enterprise to adopt the production technologies [

29]. In addition, increased FESTs could provide good external support for the production-technology innovation of enterprises and encourage them to introduce clean production technologies and management methods to reduce the demand for polluting resources. In this vein, combined with the theory model in

Appendix A1, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). FESTs improve the environment by increasing R&D.

Most studies ignore the willingness of governments to engage with FESTs, which results in omission errors, especially for the Chinese policy system. Fiscal policy plays a key role in the accumulation and allocation of an economy’s resources [

16,

30]. The classic pollution haven hypothesis (PHH) suggests that the strict enforcements of environmental regulations in developed countries increase the production costs of enterprises, thus making economically underdeveloped countries safe havens for highly polluting industries [

31]. However, the Porter Hypothesis argues that environmental regulation and corporate competitiveness should be complementary rather than mutually exclusive. The results about environmental regulations on environmental pollution are mixed.

In China, FESTs are major driving forces for innovation. The 3rd Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee clearly stated that it is necessary to “improve the government’s support mechanism for basic, strategic, cutting-edge scientific research and common technology research.” [

32]. Thus, local governments are more willing to inject limited financial resources into FESTs, which plays a significant role in crowding out fixed assets investment. During the past decades, large-scale investments have been the main driving force for local economic growth. New enterprises can enjoy new profitable opportunities by improving production efficiencies, i.e., the innovation compensation effects brought by FESTs [

33]. Thus, the enterprises will increase green production efficiency instead of traditional large-scale investments. Third, engaging with FESTs on behalf of the government allows enterprises to cooperate with the government to reduce pollution by decreasing fixed assets investment. According to previous literature, firms can access more finances and government subsidies [

34].

In addition, strict environmental regulation may create the latecomer advantage. This means that new enterprises can enjoy new profitable opportunities by improving production efficiencies, i.e., the innovation compensation effects [

35,

36]. In a country whose economic growth relies on governments and investments, large-scale investments are still the main driving force for local economic growth. Adjusting public expenditure structure may supplement government’s environmental regulations with lower costs. In this vein, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). FESTs improve the environment by strengthening environmental regulation, which in turn strengthen the supervision of enterprises and reduce fixed assets investments.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This paper focuses on the performance of local governments as public service providers in pollution control and environmental governance. We present comprehensive theoretical and empirical examination of fiscal expenditure on the environmental pollution. We adopted 260 prefecture-level cities data during the 2004–2015 period, to assess how FESTs affected environmental pollution. The results showed that, for every 1% increase in FESTs, SO2 emissions were reduced by 5.293%, but the FESTs could not alleviate PM2.5 concentration or wastewater emission. This may be because external influences allow local governments to choose direct capital expenditures to promote economic growth and provide less public service for non-productive expenditure.

Moreover, we found that FESTs promoted R&D expenditure and impeded fixed asset investments, which together led to a reduction of the total pollution. The increase in FESTs could provide good external support for enterprises’ production-technology innovation and introduction of clean production technology while reducing the demand for polluting resources. We also identified the effects of FESTs on improving the environment by strengthening environmental regulation. The increase in FESTs show that the government recognizes the importance of environmental regulations, strengthens the supervision of enterprises, and increases the cost of producing polluting products, thereby effectively reducing investment in fixed assets.

To address potential endogeneity and introduce dynamic mechanisms, our study adopted the fixed effect model, the 2SLS method, and the GMM method, which can greatly reduce the omitted variable biases to ensure the accuracy of the results. By using tests that included alternative econometric specification and using the instrumental variable method to overcome possible endogeneity, we proved that the results were robust to a series of tests. To summarize, our findings confirmed the effectiveness of government pollution control tactics.

Our findings reinforce understanding of environmental impact of FESTs for policymakers of developing countries. These results may have important implications given the current emphasis on fiscal spending to palliate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The central Chinese government also emphasizes FESTs, social spending, and environmental protection. However, under the inter-regional competition framework, local governments are more willing to inject limited financial resources into infrastructure, which plays a significant role in crowding out those FESTs with long development cycles and obvious externalities. Logically, local governments will invest fiscal funds directly in areas where performance and economic growth are prominent or in areas where investment returns are attractive, thereby reducing spending on public services such as science and technology, health care, and environmental protection. The institutional dilemma behind China’s fiscal expenditure structure, namely, political promotion incentives and performance evaluation standards centered on GDP growth, has led local governments to focus on economic growth.

Based on the above analysis, we propose the following suggestions:

Due to the problem of market failure and free-riders, it is necessary to strengthen the emphasis on environmental costs and ecological benefits in the assessment system and increase the proportion of “green GDP” in GDP [

5]. The institutional dilemma behind China’s fiscal expenditure structure, namely, political promotion incentives and performance evaluation standards centered on GDP growth, has led local governments to focus on economic growth. FESTs should be regarded as an important positive indicator when conducting performance evaluation of local officials because FESTs constitute the most direct innovation for the country [

27,

58]. Empirical studies generally support the idea that FESTs provide incentives or leverage for enterprises’ own R&D investment [

59,

60]. In addition, FESTs can play a role in guiding funds because they help to attract more external private investment, thereby contributing to the optimization of technical structure. Finally, FESTs can eliminate the R&D risks for those innovation activities with long development cycles and uncertainties.

On the other hand, regarding the other control variables, the inverse U-shaped curve shows that pollution emissions caused by GDP growth competition have declined. As the biggest emerging market, China has been experiencing a transition towards high value orientation. However, serious environmental pollution is a threat to China’s sustainable development. Besides that, the environmental regulations, economic structure, and trade openness are conductive to reducing environmental pollution. Thus, the government should further widen the openness to foreign capital and deepen economic reforms which helpful to stimulate economic growth and reduce environment pollution. Lastly, government should motivate corporations to adopt cleaner technologies through subsidies and stricter environmental regulations. This approach could also be a valuable strategy to governments outside China.