Menstrual Hygiene Preparedness Among Schools in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of System-and Policy-Level Actions

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Question

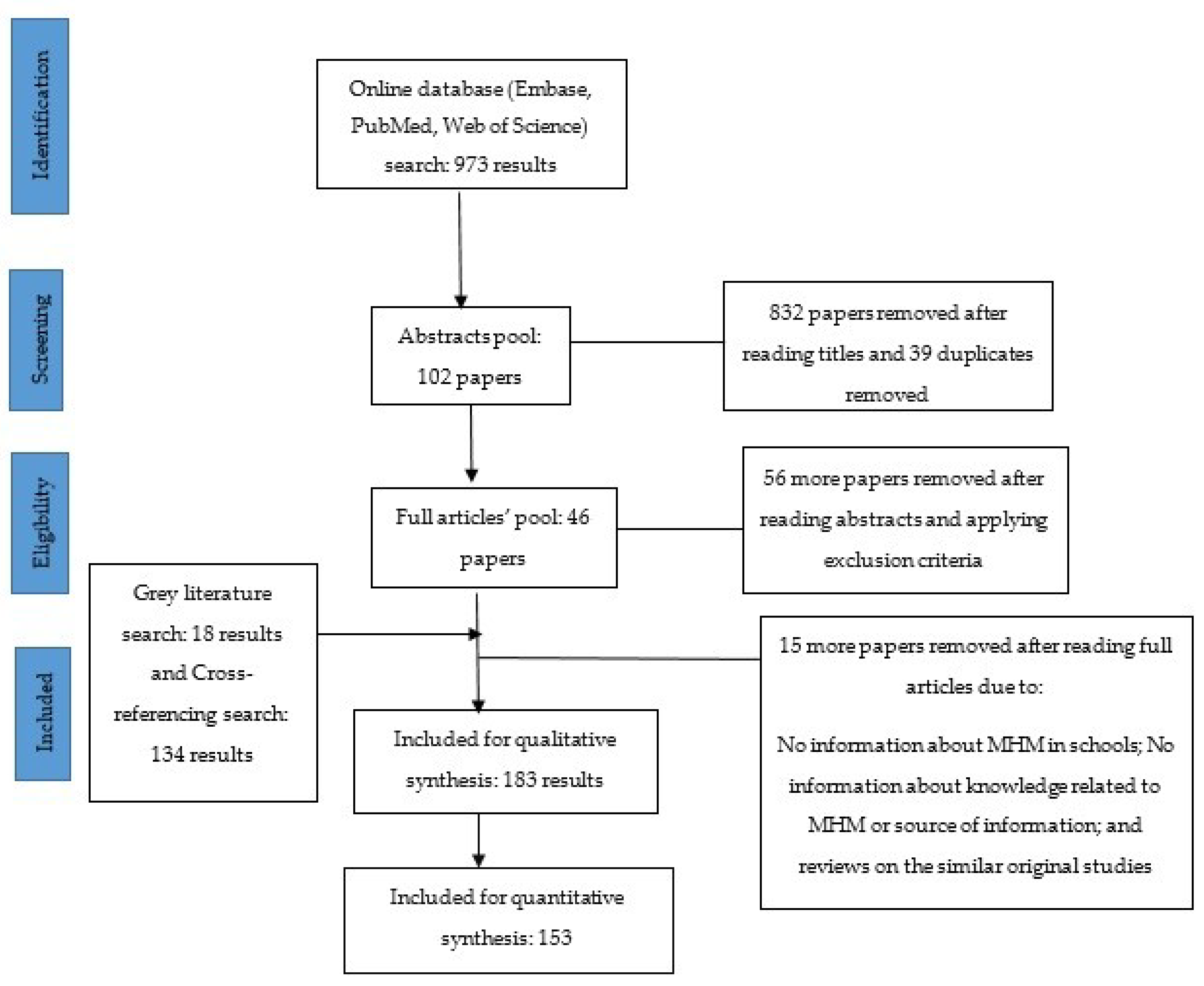

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

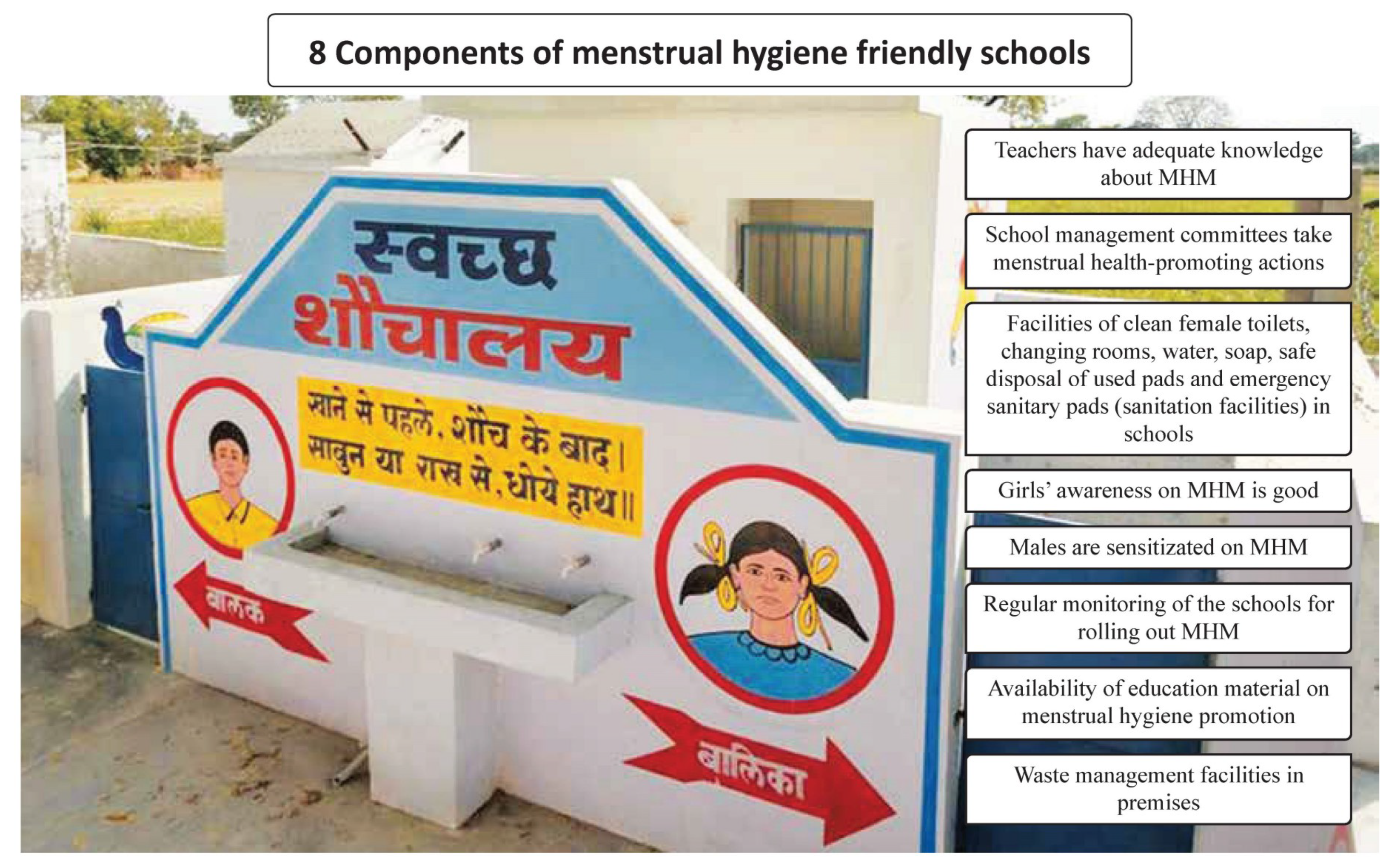

3.1. School-Level Actions (System)

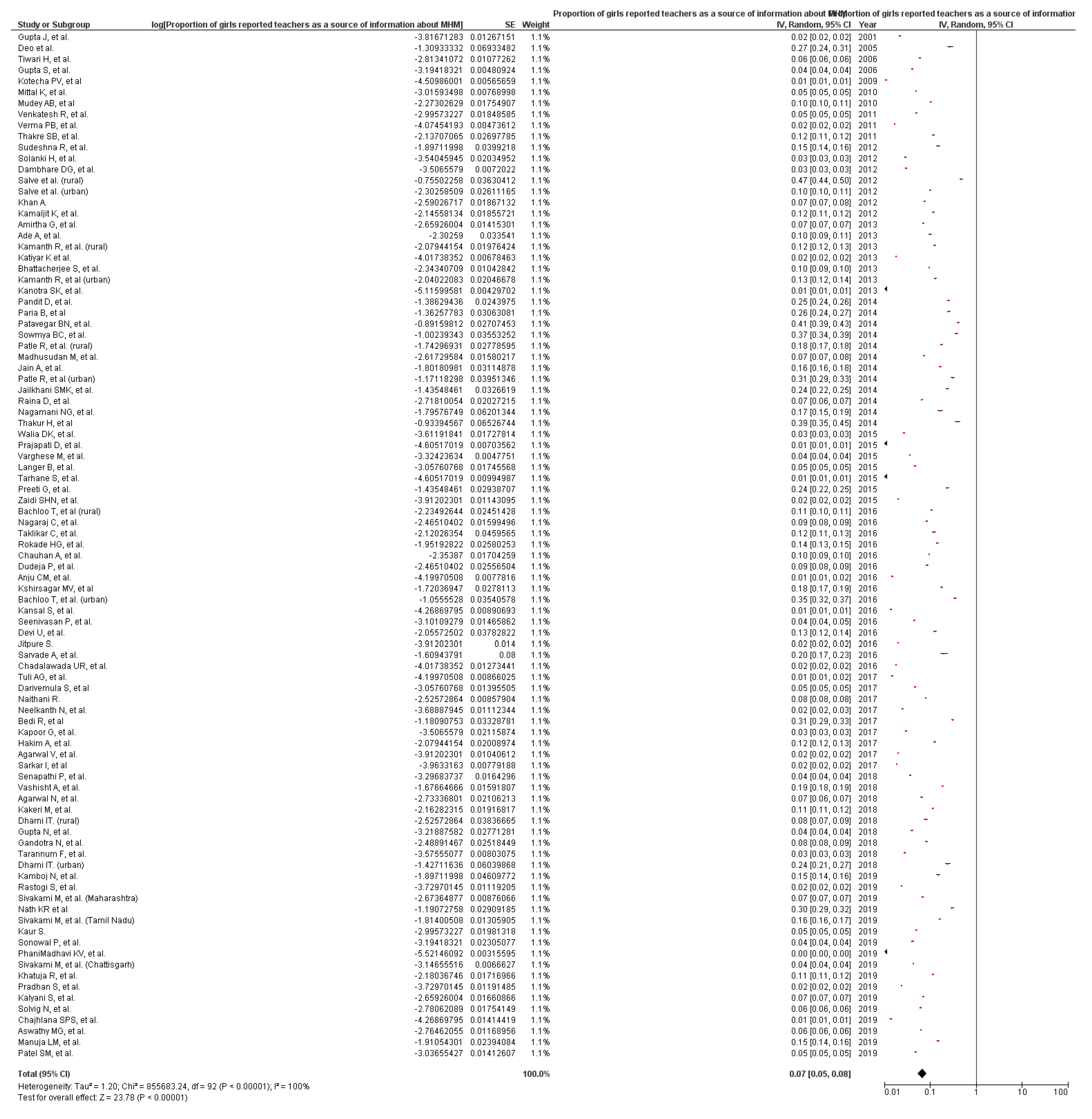

3.1.1. Menstrual Hygiene Knowledge Among School Teachers

3.1.2. School Management Committee Taking Menstrual Health-Promoting Actions

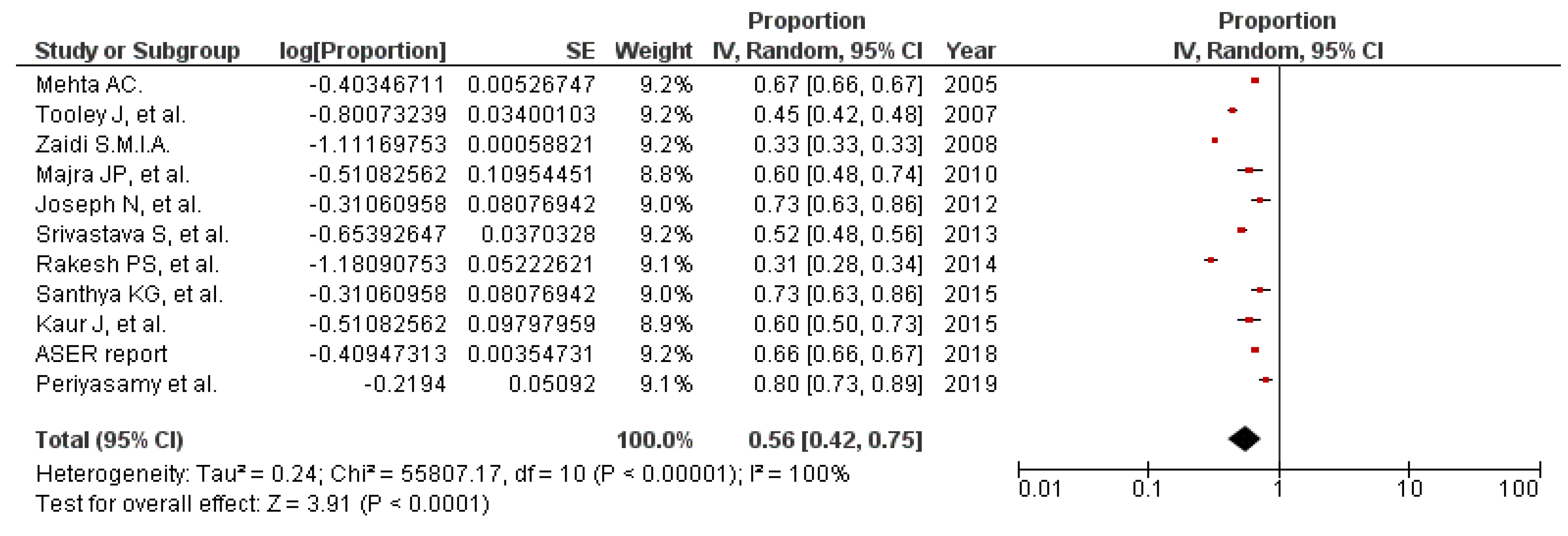

3.1.3. Sanitation Facilities in Schools

3.1.4. Sensitization of Boys and Male Teachers on MHM

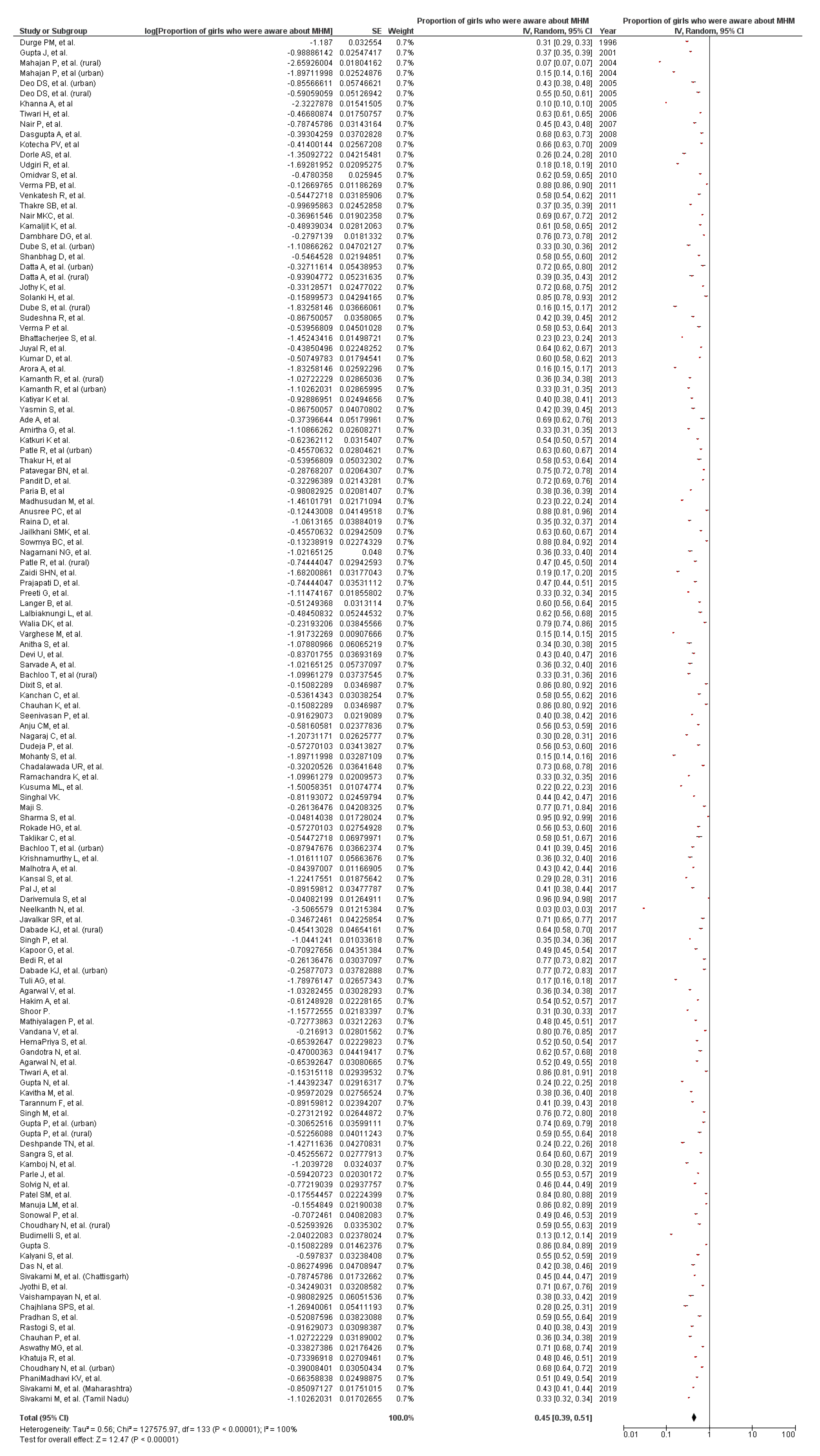

3.1.5. Girls’ Awareness of MHM

3.1.6. Education Material for Menstrual Hygiene Promotion in Schools

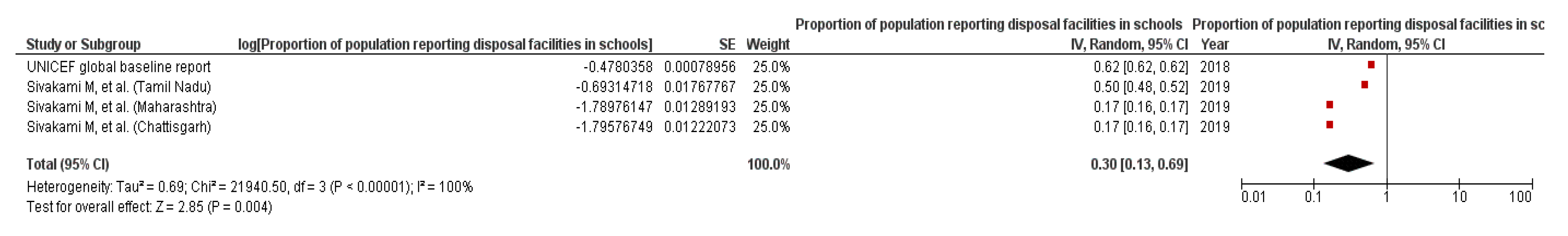

3.1.7. Facilities for Waste Management in Schools

3.1.8. Monitoring of Schools for MHM Friendly Services

Policy-Level Actions to Address MHM in Schools

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sommer, M.; Sahin, M. Overcoming the taboo: Advancing the global agenda for menstrual hygiene management for schoolgirls. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1556–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. Demographics. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/adolescents/demographics/ (accessed on 20 September 2018).

- Government of India. Census 2011. Available online: http://censusindia.gov.in/Census_And_You/age_structure_and_marital_status.aspx (accessed on 5 August 2018).

- Geertz, A.; Iyer, L.; Kasen, P.; Mazzola, F.; Peterson, K. Menstrual health in India: Country’s Landscape Analysis. Available online: http://menstrualhygieneday.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/FSG-Menstrual-Health-Landscape_India.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2018).

- Keatman, T.; Cavill, S.; Mahon, T. Menstrual Hygiene Management in Schools in South Asia, Synthesis Report; Water Aid: New Delhi, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- National Rural Health Mission. Training Module for ASHA on Menstrual Hygiene; National Rural Health Mission: New Delhi, India, 2011.

- Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation. Menstrual Hygiene Management, National Guidelines; Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation: New Delhi, India, 2015.

- Priyadarshani, S. Bollywood Takes on Menstrual Hygiene. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-02515-y (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Government of India. Operational Guidelines for Menstrual Hygiene Promotion among Adolescent Girls (10–19 Years) in Rural Areas; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2011.

- Mahon, T.; Fernandes, M. Menstrual hygiene in South Asia: A neglected issue for WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) programmes. Gend. Dev. 2010, 18, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, M.; Sutherland, C.; Chandra-Mouli, V. Putting menarche and girls into the global population health agenda. Reprod. Health 2015, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, J.; Sommer, M. Menstruation and body awareness: Linking girls’ health with girls’ education. In Special on Gender and Health; Royal Tropical Institute (KIT): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- National Council of Education Research Training. 8th All India School Education Surveys: A Concised Report, 1st ed.; NCEET Publications: New Delhi, India, 2016.

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eijk, A.M.; Sivakami, M.; Thakkar, M.B.; Bauman, A.; Laserson, K.F.; Coates, S.; Phillips-Howard, P.A. Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent girls in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Gupta, H. Adolescents and Menstruation. J. Fam. Welf. 2001, 47, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Sinha, A. Awareness about reproduction and adolescent changes among school girls of different socioeconomic status. J. Obstet. Gynecol. India 2006, 56, 324–328. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, H.; Oza, U.N.; Tiwari, R. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about menarche of adolescent girls in Anand district, Gujarat. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2006, 12, 428–433. [Google Scholar]

- Kotecha, P.V.; Patel, S.; Baxi, R.K.; Mazumdar, V.S.; Misra, S.; Modi, E.; Diwanji, M. Reproductive health awareness among rural school going adolescents of Vadodara district. Indian J. Sex. Transm. Dis. AIDS 2009, 30, 94. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, K.; Goel, M.K. Knowledge regarding reproductive health among urban adolescent girls of Haryana. Indian J. Community Med. 2010, 35, 529–530. [Google Scholar]

- Mudey, A.; Kesharwani, N.; Mudey, G.A.; Goyal, R.C. A cross-sectional study on awareness regarding safe and hygienic practices amongst school going adolescent girls in rural area of Wardha District, India. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2010, 2, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.B.; Pandya, C.M.; Ramanuj, V.A.; Singh, M.P. Menstrual pattern of adolescent school girls of Bhavnagar (Gujarat). Natl. J. Integr. Res. Med. 2011, 2, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Thakre, S.B.; Thakre, S.S.; Reddy, M.; Rathi, N.; Pathak, K.; Ughade, S. Menstrual hygiene: Knowledge and practice among adolescent school girls of Saoner, Nagpur District. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2011, 5, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, R.; Dhoundiyal, M. Perceptions and practices during menstruation among adolescent girls in and around Bangalore city. Indian J. Matern. Child Health 2011, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kamaljit, K.; Balwinder, A.; Singh, G.K.; Neki, N.S. Social beliefs and practices associated with menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls of Amritsar, Punjab, India. J. Int. Med. Sci. Acad. 2012, 25, 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sudeshna, R.; Aparajita, D. Determinants of menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls: A multivariate analysis. Natl. J. Community Med. 2012, 3, 294–301. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. Perceptions and practices about menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in a rural area-a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2012, 2, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Solanki, H.; Gosalia, V.; Patel, H.; Vora, F.; Singh, M.P. A study of menstrual problems and practices among girls of Mahila College. Natl. J. Integr. Res. Med. 2012, 3, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dambhare, D.G.; Wagh, S.V.; Dudhe, J.Y. Age at menarche and menstrual cycle pattern among school adolescent girls in Central India. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2012, 4, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade, A.; Patil, R. Menstrual hygiene and practices of rural adolescent girls of Raichur. Int. J. Biol. Med. Res. 2013, 42, 3014–3017. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacherjee, S.; Ray, K.; Biswas, R.; Chakraborty, M. Menstruation: Experiences of adolescent slum dwelling girls of Siliguri City, West Bengal, India. J. Basic Clin. Reprod. Sci. 2013, 2, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanotra, S.K.; Bangal, V.B.; Bhavthankar, D.P. Menstrual pattern and problems among rural adolescent girls. Int. J. Biomed. Adv. Res. 2013, 4, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamanth, R.; Ghosh, D.; Lena, A.; Chandrasekaran, V. A study on knowledge and practices regarding menstrual hygiene among rural and urban adolescent girls in Udipi Taluk, Manipal, India. Glob. J. Med. Public Health 2013, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Amirtha, G.; Premarajan, K.C.; Sarkar, S.; Lakshminarayanan, S. Menstrual health-Knowledge, practices and needs of adolescent school girls in Pondicherry. Indian J. Matern. Child Health 2013, 15, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Katiyar, K.; Chopra, H.; Garg, S.K.; Bajpai, S.K.; Bano, T.; Jain, S.; Kumar, A. KAP study of menstrual problems in adolescent females in an urban area of Meerut. Indian J. Community Health 2013, 25, 217–220. [Google Scholar]

- Nagamani, N.G.; Krishnaveni, A.; Naidu, S.; Sreegiri, S. A study on menstrual practices among adolescent girls residing in urban slums of Visakhapatnam city of Andhra Pradesh State. Int. J. Res. Med. 2014, 3, 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Raina, D.; Balodi, G. Menstrual hygiene: Knowledge, practise and restrictions amongst girls of Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India. Glob. J. Interdiscip. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 156–162. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.; Aswar, N.R.; Domple, V.K.; Doibale Mohan, K.; Barure Balaji, S. Menstrual hygiene awareness among rural unmarried girls. J. Evol. Med. Dent Sci. 2014, 3, 1413–1419. [Google Scholar]

- Madhusudan, M.; Chaluvaraj, T.S.; Chaitra, M.M.; Ankitha, S.; Pavithra, M.S.; Mahadeva Urthy, T.S. Menstrual hygiene: Knowledge and practice among secondary school girls of Hosakote, rural Bangalore. Int. J. Basic Appl. Med. Sci. 2014, 4, 313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Prajapati, D.J.; Shah, J.P.; Khedia, G. Menstrual hygiene: Knowledge and practice among adolescent girls of rural Kheda. Natl. J. Community Med. 2015, 6, 349–353. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi, S.H.N.; Sivakami, A.; Ramasamy, J. Menstrual hygiene and sanitation practices among adolescent school going girls: A study from a South Indian town. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2015, 2, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, B.; Mahajan, R.; Gupta, R.K.; Kumari, R.; Jan, R.; Mahajan, R. Impact of menstrual awareness and knowledge among adolescents in a rural area. Indian J. Community Health 2015, 27, 456–461. [Google Scholar]

- Preeti, G.; Amaresh, B.; Singh, H.; Lakshmi, A.; Srinivas, K.; Singh, G. A cross sectional study of knowledge, attitude and practices regarding menstrual pattern in adolescent girl. J. Evid. Based Med. Healthc. 2015, 2, 3933–3939. [Google Scholar]

- Varghese, M.; Ravichandran, M.; Karunai Anandhan, A. Knowledge and practice of menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls. Ind. J. Youth Adol. Health 2015, 2, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Walia, D.K.; Yadav, R.J.; Pandey, A.; Bakshi, R.K. Menstrual patterns among school going adolescent girls in Chandigarh and rural areas of Himachal Pradesh, North India. Natl. J. Community Med. 2015, 6, 583–586. [Google Scholar]

- Tarhane, S.; Kasulkar, A. Awareness of adolescent girls regarding menstruation and practices during menstrual cycle. Panacea J. Med. Sci. 2015, 5, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chadalawada, U.R.; Kala, S. Assessment of menstrual hygiene practices among adolescent girls. Stanley Med. J. 2016, 3, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kansal, S.; Singh, S.; Kumar, A. Menstrual hygiene practices in context of schooling: A community study among rural adolescent girls in Varanasi. Indian J. Community Med. 2016, 41, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Seenivasan, P.; Priya, K.C.; Rajeswari, C.; Akshaya, C.C.; Sabharritha, G.; Sowmya, K.R.; Banu, S. Knowledge, attitude and practices related to menstruation among adolescent girls in Chennai. J. Clin. Sci. Res. 2016, 5, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshirsagar, M.V.; Mhaske, M.; Ashturkar, M.D.; Fernandez, K. Study of menstrual hygienic practices among the adolescent girls in rural area. Natl. J. Community Med. 2016, 7, 241–244. [Google Scholar]

- Dudeja, P.; Sindhu, A.; Shankar, P.; Gadekar, T. A cross-sectional study to assess awareness about menstruation in adolescent girls of an urban slum in western Maharashtra. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2016, 30, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anju, C.M.; Jesha, M.M.; Sebastian, N.M.; Haveri, S.P. Menstrual hygiene practices in a rural area of north Kerala. Int. J. Prev. Curative Community Med. 2016, 21, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, R.U.; Sivagurunathan, C.; Kumar, P.M. Awareness about menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in rural area of Kancheepuram District-Tamil Nadu. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 2016, 7, 267–269. [Google Scholar]

- Taklikar, C.; Dobe, M.; Mandal, R.M. Menstrual Hygiene Knowledge and Practice among Adolescent School Girls of Urban Slum of Chetla, Kolkata. Indian J. Hyg. Public Health 2016, 2, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraj, C.; Konapur, K.S. Effect of health education on awareness and practices related to menstruation among rural adolescent school girls in Bengaluru, Karnataka. Int. J. Prevent. Public Health Sci. 2016, 2, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, A.; Chauhan, S.K.; Bala, D.V. Menstruation and menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls of Ahmadabad city: A descriptive analysis. Int. Multispecialty J. Health 2016, 2, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sarvade, A.; Nile, R.G. Menstrual hygiene: Awareness and practices amongst adolescent girls attended school health camp in Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2016, 3, 3022–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokade, H.G.; Kumavat, A.P. Study of menstrual pattern and menstrual hygiene practices among adolescent girls. Natl. J. Community Med. 2016, 7, 398–403. [Google Scholar]

- Jitpure, S. Assessment of menstrual hygiene, menstrual practices and menstrual problems among adolescent girls living in urban slums of Bilaspur (Chhattisgarh). IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2016, 15, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Darivemula, S.; Nagoor, K.; Reddy, B.; Kahn, S.; Sekhar, C.; Basha, J. A community based study on knowledge and practices of menstrual hygiene among the adolescent girls in rural south India. J. Int. J. Curr. Adv. Res. 2017, 6, 4749–4752. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, I.; Dobe, M.; Dasgupta, A.; Basu, R.; Shahbabu, B. Determinants of menstrual hygiene among school going adolescent girls in a rural area of West Bengal. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2017, 6, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuli, A.G.; Dhar, T.; Garg, J.; Garg, N. Menstrual hygiene-knowledge and practice among adolescent school girls in rural areas of Punjab. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2017, 6, 5793–5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, A.; Rizwana, S.; Manisha; Tak, H. A cross sectional study on the knowledge, attitudes and practices towards menstrual cycle and its problems: A comparative study of government and non-government adolescent school girls. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2017, 4, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Agarwal, V.; Fancy, M.J.; Shah, H.; Agarwal, A.S.; Shah, J.H.; Singh, S. Menstrual hygiene: Knowledge and practice among adolescent girls of rural Sabarkantha district. Natl. J. Community Med. 2017, 8, 597–601. [Google Scholar]

- Neelkanth, N.; Singh, D.; Bhatia, P. A study to assess the knowledge regarding practices of menstrual hygiene and RTI among high and higher secondary school girls: An educational interventional study. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2017, 4, 4520–4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Naithani, R. A study on knowledge and practices regarding menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in Pauri, Uttarakhand. J. Mt. Res. 2017, 12, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, G.; Kumar, D. Menstrual hygiene: Knowledge and practice among adolescent school girls in rural settings. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 6, 959–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandotra, N.; Pal, R.; Maheshwari, S. Assessment of knowledge and practices of menstrual hygiene among urban adolescent girls in North India. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 7, 2825–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gupta, N.; Kariwala, P.; Dixit, A.M.; Govil, P.; Jain, P.K. A cross-sectional study on menstrual hygiene practices among school going adolescent girls (10–19 years) of Government Girls Inter College, Saifai, Etawah. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2018, 5, 4560–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Soni, N.; Singh, S.P.; Soni, G.P. Knowledge and Practice Regarding Menstrual Hygiene Among Adolescent Girls of Rural Field Practice Area of RIMS, Raipur (CG), India. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 7, 2317–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tarannum, F.; Khalique, N.; Eram, U. A community based study on age of menarche among adolescent girls in Aligarh. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2018, 5, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashisht, A.; Pathak, R.; Agarwalla, R.; Patavegar, B.N.; Panda, M. School absenteeism during menstruation amongst adolescent girls in Delhi, India. J. Fam. Community Med. 2018, 25, 163. [Google Scholar]

- Kakeri, M.; Patil, S.B.; Waghmare, R. Knowledge and practice gap for menstrual hygiene among adolescent school girls of tribal district of Maharashtra, India: A cross sectional study. Indian J. Youth Adol. Health 2018, 5, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dharni, I.T. A comparative study to assess the menstrual hygiene practices among adolescent girls of urban and rural schools of Ludhiana, Punjab. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2018, 6, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapathi, P.; Kumar, H. A comparative study of menstrual hygiene management among rural and urban adolescent girls in Mangaluru, Karnataka. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2018, 5, 2548–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswathy, M.G.; Saju, C.R.; Mundodan, J.M. Awareness and practices regarding menarche in adolescent school going girls of Thrissur educational district. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2019, 6, 755–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, S.; Khanna, A.; Mathur, P. Uncovering the challenges to menstrual health: Knowledge, attitudes and practices of adolescent girls in government schools of Delhi. Health Educ. J. 2019, 78, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakami, M.; Ejik, A.M.V.; Thakur, H.; Kakade, N.; Patil, C.; Shinde, S.; Surani, N.; Bauman, A.; Zulaika, G.; Kabir, Y.; et al. Effect of menstruation on girls and their schooling, and facilitators of menstrual hygiene management in schools: Surveys in government schools in three states in India, 2015. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, e010408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Vernekar, S.P.; Desai, A.M. A study on the knowledge, attitude and practices regarding menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in schools in a rural area of Goa. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2019, 13, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatuja, R.; Mehta, S.; Dinani, B.; Chawla, D.; Mehta, S. Menstrual health management: Knowledge and practices among adolescent girls. Trop. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 36, 283–286. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, S.; Kar, K.; Samal, B.P.; Pradhan, J. Assessment of knowledge and practice of menstrual hygiene among school going adolescent girls in an urban area of Odisha: A cross sectional study. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2019, 6, 3979–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phani Madhavi, K.V.; Paruvu, K. Menstrual hygiene and practices among adolescent girls in rural Visakhapatnam: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2019, 6, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chajhlana, S.P.S.; Amaravadhi, S.R.; Mazodi, S.D.; Kolusu, V.S. Determinants of menstrual hygiene among school going adolescent girls in urban areas of Hyderabad. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2019, 6, 2211–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonowal, P.; Talukdar, K. Menstrual hygiene knowledge and practices amongst adolescent girls in urban slums of Dibrugarh town- a cross sectional study. Galore Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2019, 4, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kamboj, N.; Chandiok, K. Knowledge and practices regarding menstrual hygiene among school going adolescent girls. J. Curr. Sci. 2019, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, S. Knowledge and attitude on menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in Kapurthala district of Punjab. Int. J. Sci. Res. Rev. 2019, 7, 3374–3379. [Google Scholar]

- Solvig, N.; Raja, L.; George, C.E.; O’Connell, B.; Gangadharan, P.; Norman, G. Analysis of knowledge of menstruation, hygiene practices, and perceptions in adolescent girls in India. Mod. Health Sci. 2019, 2, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuja, L.M.; Raghavendra, S.K.; Shashikiran, M. Menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in the rural field practice area of medical college in Mandya. Natl. J. Res. Community Med. 2019, 8, 236–239. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyani, S.; Bicholkar, A.; Cacodcar, J.A. A study of knowledge, attitude and practices regarding menstrual health among adolescent girls in North Goa. Epidem. Int. 2019, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Deo, D.S.; Ghattargi, C.H. Perceptions and practices regarding menstruation: A comparative study in urban and rural adolescent girls. Indian J. Community Med. 2005, 30, 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Salve, S.B.; Dase, R.K.; Mahajan, S.M.; Adchitre, S.A. Assessment of knowledge and practices about menstrual hygiene amongst rural and urban adolescent girls–A comparative study. Int. J. Recent Trends Sci. Technol. 2012, 3, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Paria, B.; Bhattacharyya, P.K.; Das, S. A comparative study on menstrual hygiene among urban and rural adolescent girls of West Bengal. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2014, 3, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patle, R.; Kubde, S. Comparative study on menstrual hygiene in rural and urban adolescent girls. Indian J. Med. Sci. Public Health 2014, 3, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, D.; Bhattacharyya, P.; Bhattacharya, R. Menstrual hygiene: Knowledge and practice among adolescent school girls in rural areas of West Bengal. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2014, 13, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, H.; Aronsson, A.; Bansode, S.; Stalsby Lundborg, C.; Dalvie, S.; Faxelid, E. Knowledge, practices, and restrictions related to menstruation among young women from low socioeconomic community in Mumbai, India. Front. Public Health 2014, 2, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patavegar, B.N.; Kapilashrami, M.C.; Rasheed, N.; Pathak, R. Menstrual hygiene among adolescent school girls: An in-depth cross-sectional study in an urban community. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2014, 4, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jailkhani, S.M.K.; Naik, J.D.; Thakur, M.S.; Langre, S.D.; Pandey, V.O. Patterns & problems of menstruation amongst the adolescent girls residing in the urban slum. Sch. J. Appl. Med. Sci. 2014, 2, 529–534. [Google Scholar]

- Sowmya, B.C.; Manjunatha, S.; Kumar, J. Menstrual hygiene practices among adolescent girls: A cross sectional study. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2014, 3, 7955–7961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachloo, T.; Kumar, R.; Goyal, A.; Singh, P.; Yadav, S.S.; Bhardwaj, A.; Mittal, A. A study on perception and practice of menstruation among school going adolescent girls in district Ambala Haryana, India. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2016, 3, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, R.; Choudhary, P.K.; Sharma, S.K.; Meharda, B.; Singh, D.; Sharma, R.K. Impact of health education on knowledge and practices about menstrual hygeine among rural adolescent school going girls at RHTC Srinagar, Ajmer, Rajasthan, India. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2017, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, K.R.; John, J. Menstrual Hygiene Practices among adolescent girls in a rural area of Kanyakumari District of Tamilnadu. Indian J. Youth Adolesc. Health 2019, 6, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, R.; Goyal, S.; Gupta, S. India moves towards menstrual hygiene: Subsidized sanitary napkins for rural adolescent girls—issues and challenges. Matern. Child Health J. 2012, 16, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravi, R.; Shah, P.B.; Edward, S.; Gopal, P.; Sathiyasekaran, B.W.C. Social impact of menstrual problems among adolescent school girls in rural Tamil Nadu. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2018, 30, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Promoting Health through Schools. In Report of a WHO Expert Committee on Comprehensive School Health Education and Promotion; World Health Organization Technical Report Series; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997; pp. 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shinde, S.; Pereira, B.; Khandeparkar, P.; Sharma, A.; Patton, G.; Ross, D.A.; Weiss, H.A.; Patel, V. The development and pilot testing of a multicomponent health promotion intervention (SEHER) for secondary schools in Bihar, India. Glob. Health Action 2017, 10, e1385284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, J.S.; Sharma, D.; Jaswal, N.; Bharti, B.; Grover, A.; Thind, P. Developing and implementing an accreditation system for health promoting schools in Northern India: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Thapa, S. How Functional are School Management Committees in the Present Context? CCS Working Paper No. 271. Available online: https://ccs.in/internship_papers/2012/271_how-functional-are-school-management-commitees-in-the-present-context_sijan-thapa.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2019).

- Kumar, S. Roles and functions of school management committees (SMC) of government middle schools in district Kullu of Himachal Pradesh: A case study. Sch. Res. J. Humanit. Sci. Engl. Lang. 2016, 3, 3876–3886. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, R.; Kaur, K.; Kaur, R. Menstrual Hygiene, Management, and Waste Disposal: Practices and Challenges Faced by Girls/Women of Developing Countries. J. Environ. Public Health. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); World Health Organization. Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in Schools: Global Baseline Report 2018; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); World Health Organization: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly, L.; Satpati, L. Sanitation and hygiene status among school students: A micro study on some selective schools of North Dumdum municipality area, West Bengal. Int. Res. J. Public Environ. Health 2019, 6, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Bodat, S.; Ghate, M.M.; Majumdar, J.R. School absenteeism during menstruation among rural adolescent girls in Pune. Natl. J. Community Med. 2013, 4, 212–216. [Google Scholar]

- Periyasamy, S.; Krishnappa, P.; Renuka, P. Adherence to components of health promoting schools in schools of Bengaluru, India. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 34, 1167–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S. Status of Hygiene and Sanitation Conditions in Schools, Uttar Pradesh FANSA U.P; Chapter and Shohratgarh Environmental Society. Available online: http://sesindia.org/pdf/Sanitation%20Status%20in%20Schools%20of%20U.P.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Annual Status of Education Report Centre. Annual Status of Education Report (Rural). 2018. Available online: http://img.asercentre.org/docs/ASER%202018/Release%20Material/aserreport2018.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2019).

- Mehta, A.C. Elementary Education in Unrecognised Schools in India; National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration. 2005. Available online: http://dise.in/Downloads/Publications/Publications%202005-06/Ar0506/Introduction.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Tooley, J.; Dixon, P. Private schooling for low-income families: A census and comparative survey in East Delhi, India. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2007, 27, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.M.I.A. Facilities in Primary and Upper Primary Schools in India: An Analysis of DISE Data of Selected Major States. National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration. 2004. Available online: http://www.dise.in/downloads/use%20of%20dise%20data/zaidi.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2019).

- Majra, J.P.; Gur, A. School environment and sanitation in rural India. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2010, 2, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, N.; Bhaskaran, U.; Saya, G.K.; Kotian, S.M.; Menezes, R.G. Environmental sanitation and health facilities in schools of an urban city of south India. Ann. Trop. Med. Public Health 2012, 5, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. An Overview of the Status of Drinking Water and Sanitation in Schools in India. Available online: http://www.dise.in/Downloads/best%20practices/An%20overview%20of%20status%20of%20drinking%20water%20and%20sanitation%20in%20schools%20in%20India.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2019).

- Rakesh, P.S.; Usha, S.; Subhagan, S.; Shaji, M.; Sheeja, A.L.; Subairf, F. Water quality and sanitation at schools: A cross sectional study from Kollam District, Kerala, Southern India. Kerala Med. J. 2014, 7, 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, U.L.; Kiran, J.K.; Prashanti, B. Girl Child Friendly (NPEGEL) schools and its impact on enrollment and dropout of girl child. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2014, 3, 559–562. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, J.; Saini, S.K.; Bharti, B.; Kapoor, S. Health Promotion facilities in Schools: WHO Health Promoting Schools Initiative. Nurs. Midwifery Res. J. 2015, 11, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Santhya, K.G.; Francis Zavier, A.J.; Jejeebhoy, S.J. School quality and its association with agency and academic achievements in girls and boys in secondary schools: Evidence from Bihar, India. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2015, 41, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahon, S. A study of infrastructure facilities in secondary schools of Assam state with special reference to Sivasagar District. J. Res. 2015, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, J.P. Facilities provided by the primary education schools—A study in east Godavari district of Andhra Pradesh. Int. J. Acad. Res. Dev. 2018, 3, 1605–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Padhi, S.; Priyabadini, S.; Pradhan, S.K. An assessment of institutional health for adolescent girls. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2018, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. An evaluation study of infrastructure facilities in government primary schools in Dehradun district (Uttarakhand). Samwaad eJ. 2018, 7, 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Mahon, T.; Tripathy, A.; Singh, N. Putting the men into menstruation: The role of men and boys in community menstrual hygiene management. Waterlines 2015, 34, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, J. The SoE/SBEP Gender Equity Support Program: An Early Impact Assessment. Unpublished Program Document of Sudan Basic Education Program, Nairobi, Kenya. 2005. Available online: https://www.eccnetwork.net/sites/default/files/media/file/doc_1_89_mentors_for_girls.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- Mason, L.; Sivakami, M.; Thakur, H.; Kakade, N.; Beauman, A.; Alexander, K.; Eijke, A.M.V.; Laserson, K.F.; Thakkar, M.B.; Phillips-Howard, P.A. ‘We do not know’: A qualitative study exploring boys’ perceptions of menstruation in India. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, P.; Sharma, N. Perceived parental relationship and the awareness level of adolescents regarding menarche. J. Hum. Ecol. 2004, 16, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, A.; Goyal, R.S.; Bhawsar, R. Menstrual practices and reproductive problems: A study of adolescent girls in Rajasthan. J. Health Manag. 2005, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.; Grover, V.L.; Kannan, A.T. Awareness and practices of menstruation and pubertal changes amongst unmarried female adolescents in a rural area of East Delhi. Indian J. Community Med. 2007, 32, 156–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udgiri, R.; Angadi, M.M.; Patil, S.; Sorganvi, V. Knowledge and practices regarding menstruation among adolescent girls in an urban slum, Bijapur. J. Indian Med. Assoc. 2010, 108, 514–516. [Google Scholar]

- Omidvar, S.; Begum, K. Factors influencing hygienic practices during menses among girls from south India: A cross sectional study. Int J. Collab. Res. Intern. Med. Public Health 2010, 2, 411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Dorle, A.S.; Hiremath, L.D.; Mannapur, B.S.; Ghattargi, C.H. Awareness regarding puberty changes in secondary school children of Bagalkot, Karnataka—A cross sectional study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2010, 4, 3016–3019. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, S.; Sharma, K. Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding reproductive health among urban and rural girls: A comparative study. Stud. Ethno-Med. 2012, 6, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhag, D.; Shilpa, R.; D’Souza, N.; Josephine, P.; Singh, J.; Goud, B.R. Perceptions regarding menstruation and practices during menstrual cycles among high school going adolescent girls in resource limited settings around Bangalore city, Karnataka, India. Int. J. Collab. Res. Intern. Med. Public Health 2012, 4, 1353. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, A.; Manna, N.; Datta, M.; Sarkar, J.; Baur, B.; Datta, S. Menstruation and menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls of West Bengal, India: A school based comparative study. Glob. J. Med. Public Health 2012, 1, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, P.; Ahmad, S.; Srivastava, R.K. Knowledge and practices about menstrual hygiene among higher secondary school girls. Indian J. Community Health 2013, 25, 265–271. [Google Scholar]

- Yasmin, S.; Manna, N.; Mallik, S.; Ahmed, A.; Paria, B. Menstrual hygiene among adolescent school students: An in-depth cross-sectional study in an urban community of West Bengal, India. IOSR J. Dent Med. Sci. 2013, 5, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juyal, R.; Kandpal, S.D.; Semwal, J. Social aspects of menstruation related practices in adolescent girls of district Dehradun. Indian J. Community Health 2013, 25, 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D.; Goel, N.K.; Puri, S.; Pathak, R.; Sarpal, S.S.; Gupta, S.; Arora, S. Menstrual pattern among unmarried women from Northern India. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013, 7, 1926–1929. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, A.; Mittal, A.; Pathania, D.; Singh, J.; Mehta, C.; Bunger, R. Impact of health education on knowledge and practices about menstruation among adolescent school girls of rural part of district Ambala, Haryana. Indian J. Community Health 2013, 25, 492–497. [Google Scholar]

- Katkuri, S.; Pisudde, P.; Kumar, N.; Hasan, S.F. A study to assess knowledge, attitude and practices about menstrual hygiene among school going adolescent girl’s in Hyderabad, India. J. Pharm. Biomed. Sci. 2014, 4, 298–302. [Google Scholar]

- Lalbiaknungi, L.; Roy, S.; Paul, A.; Dukpa, R. A study on menstrual hygiene and dysmenorrhea of adolescent girls in a rural population of West Bengal. J. Compr. Health 2015, 3, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Anitha, S.; Sinu, E. Menstrual Knowledge and Coping Strategies of Early Adolescent Girls: A School Based Intervention Study. J. Sch. Soc. Work 2015, 11, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, S.; Panda, M.; Tripathi, R.M. Assessment of menstrual health among school going adolescent girls of urban slums of Berhampur, Odisha, India: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2016, 3, 3440–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kanchan, C.; Prasad, V.S.V. Menstrual hygiene: Knowledge and practice among adolescent school girls. Panacea J. Med. Sci. 2016, 6, 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandra, K.; Gilyaru, S.; Eregowda, A.; Yathiraja, S. A study on knowledge and practices regarding menstrual hygiene among urban adolescent girls. Int. J. Contemp. Pediatr. 2016, 3, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, A.; Goli, S.; Cotes, S.; Mosquera-Vasquez, M. Factors associated with knowledge, attitudes, and hygiene practices during menstruation among adolescent girls in Uttar Pradesh. Waterlines 2016, 35, 277–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, L.; Ranganath, B.G.; Shruthi, M.N.; Venkatesha, M. Menstrual hygiene practices and knowledge among high school girls of Rural Kolar. Natl. J. Community Med. 2016, 7, 754–758. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, V.K. Study of menstrual hygiene of school going adolescent girls in Gurgaon, Haryana. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2016, 5, 581–583. [Google Scholar]

- Kusuma, M.L.; Ahmed, M. Awareness, perception and practices of government pre-university adolescent girls regarding menstruation in Mysore city, India. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2016, 3, 1593–1599. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, J.; Mullick, T.H. Menstrual hygiene-an unsolved issue: A school-based study among adolescent girls in a slum area of Kolkata. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2017, 16, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Bhardwaj, S.; Singh, S.; Singh, S.; Raghuvanshi, R.S. Study on hygiene and sanitary practices during menstruation among adolescent girls of Udham Singh Nagar district of Uttarakhand. Int. J. Home Sci. 2017, 3, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mathiyalagen, P.; Peramasamy, B.; Vasudevan, K.; Basu, M.; Cherian, J.; Sundar, B. A descriptive cross-sectional study on menstrual hygiene and perceived reproductive morbidity among adolescent girls in a union territory, India. J. Fam. Med. Prim Care 2017, 6, 360–365. [Google Scholar]

- Shoor, P. A study of knowledge, attitude, and practices of menstrual health among adolescent school girls in urban field practice area of medical college, Tumkur. Indian J. Health Sci. Biomed. Res. 2017, 10, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hema Priya, S.; Nandi, P.; Seetharaman, N.; Ramya, M.R.; Nishanthini, N.; Lokeshmaran, A. A study of menstrual hygiene and related personal hygiene practices among adolescent girls in rural Puducherry. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2017, 4, 2348–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, T.N.; Patil, S.S.; Gharai, S.B.; Patil, S.R.; Durgawale, P.M. Menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls – A study from urban slum area. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2018, 7, 1439–1445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, P.; Shaik, R.A.; Anusha, D.V.B.; Sotala, M. A study to assess knowledge, attitude, and practices related to menstrual cycle and management of menstrual hygiene among school-going adolescent girls in a rural area of South India. Int. J. Med. Sci. Public Health. 2019, 8, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, M.; Jadhav, J.; Ranganath, T.S.; Vishwanatha. Assessment of knowledge and menstrual hygiene management among adolescent school girls of Nelamangala. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2018, 5, 4135–4139. [Google Scholar]

- Sangra, S.; Choudhary, N.; Kouser, W.; Faizal, I. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice about menstruation and menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in rural area of district Kathua, Jammu and Kashmir. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2019, 6, 5215–5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budimelli, S.; Chebrolu, K. Determinants of menstrual hygiene among the adolescent girls in a South Indian village. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2019, 6, 3915–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Tasa, A.S. Menstrual hygiene: Knowledge and practices during menstruation among adolescent girls in urban slums of Jorhat district, Assam, India. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2019, 6, 3068–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parle, J.; Khatoon, Z. Knowledge, attitude, practice and perception about menstruation and menstrual hygiene among adolescent school girls in rural areas of Raigad district. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2019, 6, 2490–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishampayan, N.; Deshpande, S.R. Awareness of menstruation & related hygiene in adolescent girls—A comparative research study. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2019, 9, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra, R.; Kumar, A.; Kour, M. Knowledge and practices related to menstruation among tribal (Gujjar) adolescent girls. Stud. Ethno-Med. 2009, 3, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, S.; Aimol, K.R. Knowledge of adolescent girls regarding menstruation in tribal areas of Meghalya. Stud. Tribes Tribals 2010, 8, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chothe, V.; Khubchandani, J.; Seabert, D.; Asalkar, M.; Rakshe, S.; Firke, A.; Midha, I.; Simmons, R. Students’ perceptions and doubts about menstruation in developing countries: A case study from India. Health Promot. Pract. 2014, 15, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durge, P.M.; Varadpande, U. Impact assessment of health education in adolescent girls. J. Obstet. Gynecol. India 1996, 46, 368–372. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, A.; Sarkar, M. Menstrual hygiene: How hygienic is the adolescent girl? Indian J. Community Med. 2008, 33, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemade, D.; Anjenaya, S.; Gujar, R. Impact of health education on knowledge and practices about menstruation among adolescent school girls of Kalamboli, Navi-Mumbai. Health Popul. Perspect. Issues 2009, 32, 167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Jothy, K.; Kalaiselvi, S. Is menstrual hygiene and management an issue for the rural adolescent school girls? Elixir Soc Sci. 2012, 44, 7223–7228. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, M.K.C.; Paul, M.K.; Leena, M.; Thankachi, Y.; George, B.; Russell, P.S.; Pillai, H.V. Effectiveness of a reproductive sexual health education package among school going adolescents. Indian J. Pediatr. 2012, 79, S64–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusree, P.C.; Roy, A.; Sara, A.B.; Faseela, V.C.M.; Babu, G.P.; Tamrakar, A. Knowledge regarding menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in selected school, mangalore with a view to develop an information booklet. IOSR J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2014, 3, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Maji, S. A study on menstrual knowledge and practices among rural adolescent girls in Burdwan district, West Bengal. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 4, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Choudhary, S.; Saluja, N.; Gaur, D.R.; Kumari, S.; Pandey, S.M. Knowledge and practices about menstrual hygiene among school adolescent girls in Agroha village of Haryana. J. Evolution Med. Dent. Sci. 2016, 5, 389–392. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, K.; Mehta, U.; Ranaut, V. Assessment of knowledge and expressed practice regarding menstrual hygiene among the adolescent girls of govt. girls senior secondary school, Lakkar Bazar, Shimla, Himachal Pradesh. Int. J. Obstet. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2016, 2, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, S.; Raghunath, D.; Rokade, R.; Nawaz, S.A.; Nagdeve, T.; Goyal, I. Awareness about Menstruation and Menstrual Hygiene Practices among Adolescent Girls in Central India. Natl. J. Community Med. 2016, 7, 468–473. [Google Scholar]

- Javalkar, S.R.; Akshaya, K.M. Menstrual hygiene practices among adolescent schoolgirls of rural Mangalore, Karnataka. Int. J. Med. Sci. Public Health 2017, 6, 1145–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandana, V.; Simarjeet, K.; Neetu. Menstruation and menstrual hygiene practices of adolescent school going girls: A descriptive study. World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 6, 2090–2102. [Google Scholar]

- Dabade, K.J.; Dabade, S.K. Comparative study of awareness and practices regarding menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls residing in urban and rural area. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2017, 4, 1284–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Ekka, I.J.; Thakur, R. Assessment of knowledge and practices regarding menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls of Government higher secondary school, station Murhipar, Rajnandgaon (C.G.). Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2018, 5, 1335–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gupta, P.; Gupta, J.; Singhal, G.; Meharda, B. Knowledge and practices pertaining to menstruation among the school going adolescent girls of UHTC/RHTC area of Government Medical College, Kota, Rajasthan. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2018, 5, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Singh, M.; Kundu, M.; Ray, S.; Jain, A. Menstrual hygiene and college absenteeism among medical students, Gurugram. J. Med. Sci. Clin. Res. 2018, 6, 423–427. [Google Scholar]

- Jyothi, B.; Hurakadli, K. Knowledge, practice and attitude of menstrual hygiene among school going adolescent girls: An interventional study in an urban school of Bagalkot city. Med. Innov. 2019, 8, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, N.; Gupta, M.K. A comparative study of perception and practices regarding menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls in urban and rural areas of Jodhpur district, Rajasthan. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 875–880. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S. An empirical study of managing menstrual hygiene in schools (A special reference to Government Upper Primary Schools in District Sambhal (Uttar Pradesh). Integr. J. Soc Sci. 2019, 6, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW). Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakaram: Operational framework translating strategy into programmes. Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Management Centre (UMC). The ABC of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Improvement in Schools; ASAL: Gujarat, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mailman School of Public Health. MHM in TEN: Advancing the MHM Agenda in Teen; Third Annual Meeting; UNICEF; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Human Resource Development (MoHRD). Clean India, Clean Schools: A Handbook; MoHRD: New Delhi, India, 2016.

- Sinha, R.N.; Paul, B. Menstrual hygiene management in India: The concerns. Indian J. Public Health 2018, 62, 71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DASRA. Spot On! Improving Menstrual Health and Hygiene in India, Report; DASRA: Delhi, India, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, G. Celebrating Womanhood: How Better Menstrual Hygiene Management Is the Path to Better Health, Dignity and Business; Report; Water Supply & Sanitation Collaborative Council: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Toolkit on Hygiene, Sanitation and Water in Schools; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, M.; Figueroa, C.; Kwauk, C.; Jones, M.; Fyles, N. Attention to menstrual hygiene management in schools: An analysis of education policy documents in low- and middle-income countries. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2017, 57, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, R.; Page, E. Changing Discriminatory Norms Affecting Adolescent Girls through Communication Activities. A Review of Evidence; ODI: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Muralidharan, A.; Patil, H.; Patnaik, S. Unpacking the policy landscape for menstrual hygiene management: Implications for school WASH programmes in India. Waterlines 2015, 34, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips-Howard, P.A.; Caruso, B.; Torondel, B.; Zulaika, G.; Sahin, M.; Sommer, M. Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent schoolgirls in low- and middle-income countries: Research priorities. Glob. Health Action 2016, 9, 33032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra-Mouli, V.; Patel, S.V. Mapping the knowledge and understanding of menarche, menstrual hygiene and menstrual health among adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennegan, J.; Shannon, A.K.; Rubli, J.; Schwab, K.J.; Melendez-Torres, G.J. Women’s and girls’ experiences of menstruation in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS); ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–2016; IIPS: Mumbai, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, J.; Rietdijk, W.; Pickett, K. Teachers as health promoters: Factors that influence early career teachers to engage with health and wellbeing education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 69, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, M.; Mumtaz, Z.; Bhatti, A. Formative Menstrual Hygiene Management Research: Adolescent Girls in Baluchistan; Real Medicine Foundation: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj, S.; Patkar, A. Menstrual Hygiene and Management in Developing Countries: Taking Stock; Junction Social: Mumbai, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Katti, V.S.; Pimple, Y.; Saraf, A. Menstrual Hygiene in Rural India. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2017, 8, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Advancing WASH in Schools Monitoring; Working Paper; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sarah, H.; Mahon, T.; Cavill, S. Module six: Menstrual hygiene matters. In A Resource for Improving Menstrual Hygiene around the World, 1st ed.; Water Aid: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vatsalya. Woman with Wings: Celebrating Womanhood, Menstrual Hygiene Management. Available online: http://vatsalya.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Women-with-wings.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2018).

- Ina, J. WASH United‘s Menstrual Hygiene Management Training for Girls, Boys and Teachers Report; WASH United: Berlin, Germany; Available online: http://www.unicef.org/wash/schools/files/3.5_Jurga.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2018).

- Sharma, S.; Arora, K. Menstrual Hygiene Friendly Schools in India: A Need to Translate Research into Actions. Available online: https://mamtahimc.wordpress.com/2018/12/29/menstrual-hygiene-friendly-schools-in-india-a-need-to-translate-research-into-actions/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Laganà, A.S.; La Rosa, V.L.; Rapisarda, A.M.C.; Valenti, G.; Sapia, F.; Chiofalo, B.; Rossetti, D.; Ban Frangež, H.; Vrtačnik Bokal, E.; Vitale, S.G. Anxiety and depression in patients with endometriosis: Impact and management challenges. Int. J. Womens Health 2017, 9, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Serial Number | Variables | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| School–Level Actions | N = 176 | |

| 1 | Type of publications | |

| Original research | 163 (92.6) | |

| Review articles | 4 (2.3) | |

| Reports | 9 (5.1) | |

| 2 | Year of publication | |

| 1990–2005 | 8 (4.5) | |

| 2006–2011 | 19 (10.8) | |

| 2012–2017 | 103 (58.5) | |

| 2018–2019 | 46 (26.2) | |

| 3 | Study design of original research (n = 163) | |

| Cross-section study | 153 (94.0) | |

| Intervention study | 10 (6.0) | |

| 4 | Study population in original research (n = 163) | |

| Girls | 148 (90.7) | |

| Other populations only (teachers and boys) | 3 (1.9) | |

| Schools | 12 (7.4) | |

| 5 | Settings in original research (n = 163) | |

| Rural | 62 (38.0) | |

| Urban and slums | 42 (25.7) | |

| Both rural and urban | 28 (17.2) | |

| Not clear from the study | 31 (19.1) | |

| 6 | Methods of data collection in original research (n =163) | |

| Self-administered | 67 (41.1) | |

| Questions asked by investigators | 76 (46.6) | |

| Not clear from the study | 20 (12.3) | |

| 7 | Region (n = 163) ¶ | |

| North India | 30 (18.4) | |

| South India | 52 (31.9) | |

| East India | 22 (13.5) | |

| West India | 38 (23.4) | |

| Central India | 19 (11.6) | |

| Mixed regions | 2 (1.2) | |

| 8 | Median sample size for (n = 160) | |

| Adolescent girls (n = 148) | 250 | |

| Schools (n = 12) | 28 | |

| Policy-level actions | N = 7 | |

| 1 | Type of documents | |

| Guidelines | 4 (57.1) | |

| Reports | 2 (28.5) | |

| Article | 1 (14.4) | |

| 2 | Year of publication | |

| 2014–2017 | 5 (71.4) | |

| 2018–2019 | 2 (28.6) |

| First Author | Year of Publication | Sample Size † | Sample Size ‡ | Location of the Study | Type of Area | Data Collection Method | Percent Awareness * | Percent Teachers as a Source ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Durge et al. | 1996 | 200 | - | Nagpur, Maharashtra | Urban | Unclear | 30.5 | - |

| Gupta et al. | 2001 | 360 | 134 | Jaipur, Rajasthan | Unclear | Self-administered | 37.2 | 2.2 |

| Mahajan et al. | 2004 | 400 (Rural: 200; Urban: 200) | - | Jammu | Rural and urban | Self-administered | Rural:7.0 Urban:15.0 | - |

| Deo et al. | 2005 | 168 (Rural: 74; Urban: 94) | Rural: 41 Urban: NA | Ambajogai, Maharashtra | Rural and urban | Unclear | Rural:55.4 Urban:42.5 | 27.0 |

| Khanna et al. | 2005 | 372 | - | Ajmer, Rajasthan | Rural and urban | Interview | 9.8 | - |

| Gupta et al. | 2006 | - | 1700 | Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh | Urban | Self-administered | - | 4.1 |

| Tiwari et al. | 2006 | 763 | 486 | Anand, Gujarat | Unclear | Self-administered | 62.7 | 6.0 |

| Nair et al. | 2007 | 251 | - | Delhi | Rural | Interview | 45.5 | - |

| Dasgupta et al. | 2008 | 160 | - | Hooghly, West Bengal | Rural | Self-administered | 67.5 | - |

| Nemade et al. | 2009 | 217 | - | Maharashtra | Unclear | Unclear | 100.0 | - |

| Kotecha et al. | 2009 | 340 | 340 | Vadodra, Gujarat | Rural | Self-administered | 66.1 | 1.1 |

| Mittal et al. | 2010 | - | 788 | Rohtak, Haryana | Urban | Interview | - | 4.9 |

| Udgiri et al. | 2010 | 342 | - | Bijapur, Karnataka | Urban | Unclear | 18.4 | - |

| Mudey et al. | 2010 | - | 300 | Wardha, Maharashtra | Rural | Self-administered | - | 10.3 |

| Omidvar et al. | 2010 | 350 | - | South India | Urban | Self-administered | 62.0 | - |

| Dorle et al. | 2010 | 108 | - | Bagalkot, Karnataka | Unclear | Self-administered | 25.9 | - |

| Verma et al. | 2011 | 745 | 745 | Bhavnagar, Gujarat | Urban | Self-administered | 88.1 | 1.7 |

| Thakre et al. | 2011 | 387 | 143 | Nagpur, Maharashtra | Rural and urban | Interview | 36.9 | 11.8 |

| Venkatesh et al. | 2011 | 240 | 139 | Bangalore, Karnataka | Rural and urban slums | Interview | 58.0 | 5.0 |

| Dube et al. | 2012 | 200 (Rural: 100; Urban: 100) | - | Jaipur, Rajasthan | Rural and urban | Self-administered | Rural:16.0 Urban: 33.0 | - |

| Jothy et al. | 2012 | 330 | - | Cuddalore, Tamil Nadu | Rural | Interview | 71.8 | - |

| Kamaljit et al. | 2012 | 300 | 300 | Amritsar, Punjab | Urban | Interview | 61.3 | 11.7 |

| Shanbhag et al. | 2012 | 506 | - | Bangalore, Karnataka | Rural | Self-administered | 57.9 | - |

| Sudeshna et al. | 2012 | 190 | 80 | Hooghly, West Bengal | Rural | Self-administered | 42.0 | 15.0 |

| Datta et al. | 2012 | 155 (Rural: 87; Urban: 68) | - | Howrah, West Bengal | Rural and urban | Self-administered | Rural: 39.1 Urban: 72.1 | - |

| Khan. | 2012 | - | 199 | Bellur, Karnataka | Rural | Interview | - | 7.5 |

| Solanki et al. | 2012 | 68 | 68 | Bhavnagar, Gujarat | Unclear | Self-administered | 85.3 | 2.9 |

| Dambhare et al. | 2012 | 561 (Rural: 390; Urban: 171) | 561 | Wardha, Maharashtra | Rural and urban | Self-administered | 75.6 | 3.0 |

| Salve et al. | 2012 | - | Rural: 189 Urban: 132 | Auranganbad, Maharashtra | Rural and urban | Interview | - | Rural: 47.0 Urban: 10.0 |

| Nair et al. | 2012 | 590 | - | Thiruvanantha-puram, Kerala | Rural and urban | Self-administered | 69.1 | - |

| Verma et al. | 2013 | 120 | - | Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh | Unclear | Interview | 58.3 | - |

| Yasmin et al. | 2013 | 147 | - | Kolkata, West Bengal | Urban | Self-administered | 42.0 | - |

| Ade et al. | 2013 | 80 | 80 | Raichur, Karnataka | Rural | Self-administered | 68.8 | <10.0 |

| Bhattacherjee et al. | 2013 | 798 | 798 | Siliguri, West Bengal | Slums | Interview | 23.4 | 9.6 |

| Juyal et al. | 2013 | 453 | - | Dehradun, Uttarakhand | Rural and semi-urban | Interview | 64.5 | - |

| Kanotra et al. | 2013 | - | 323 | Maharashtra | Rural | Self-administered | - | 0.6 |

| Kumar et al. | 2013 | 744 | - | Chandigarh | Rural and urban | Interview | 60.2 | - |

| Kamanth et al. | 2013 | 550 (Rural: 280; Urban: 270) | 550 (Rural: 280; Urban: 270) | Udupi, Karnataka | Rural and urban | Self-administered | Rural: 35.8 Urban: 33.2 | Rural: 12.5 Urban: 13.0 |

| Amirtha et al. | 2013 | 325 | 325 | Puducherry | Urban | Self-administered | 33.0 | 7.0 |

| Arora et al. | 2013 | 200 | - | Ambala, Haryana | Rural | Self-administered | 16.0 | - |

| Katiyar et al. | 2013 | 384 | 384 | Meerut, Uttar Pradesh | Urban | Interview | 39.5 | 1.8 |

| Paria et al. | 2014 | 541 | 203 | Kolkata, West Bengal | Rural and urban | Self-administered | 37.5 | 25.6 |

| Katkuri et al. | 2014 | 250 | - | Hyderabad | Unclear | Self-administered | 53.6 | - |

| Nagamani et al. | 2014 | 100 | 36 | Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh | Urban slums | Interview | 36.0 | 16.6 |

| Raina et al. | 2014 | 150 | 150 | Dehradun, Uttarakhand | Rural | Interview | 34.6 | 6.6 |

| Patle et al. | 2014 | 583 (Rural: 288; urban: 295) | 324 (Rural: 187; urban: 137) | Nagpur, Maharashtra | Rural and urban | Interview | Rural: 47.5 Urban: 63.4 | Rural: 17.5 Urban: 31.0 |

| Pandit et al. | 2014 | 435 | 315 | Hooghly, West Bengal | Rural | Interview | 72.4 | 25.0 |

| Thakur et al. | 2014 | 96 | 56 | Mumbai, Maharashtra | Urban | Interview | 58.3 | 39.3 |

| Patavegar et al. | 2014 | 440 | 330 | Pulpralhadpur, Delhi | Urban | Self-administered | 75.0 | 41.0 |

| Anusree et al. | 2014 | 60 | - | Mangalore, Karnataka | Unclear | Self-administered | 88.3 | - |

| Jailkhani et al. | 2014 | 268 | 170 | Maharashtra | Urban slums | Interview | 63.4 | 23.8 |

| Sowmya et al. | 2014 | 210 | 184 | Bangalore, Karnataka | Rural | Interview | 87.6 | 36.7 |

| Jain et al. | 2014 | - | 142 | Nanded, Maharashtra | Rural | Interview | - | 16.5 |

| Madhusudan et al. | 2014 | 378 | 271 | Hosakote, Karnataka | Rural | Self-administered | 23.2 | 7.3 |

| Lalbiaknungi et al. | 2015 | 86 | - | Bhatar, West Bengal | Rural | Interview | 61.6 | - |

| Prajapati et al. | 2015 | 200 | 200 | Kheda, Gujarat | Rural | Interview | 47.5 | 1.0 |

| Zaidi et al. | 2015 | 150 | 150 | Thiruporur, Tamil Nadu | Unclear | Interview | 18.6 | 2.0 |

| Langer et al. | 2015 | 245 | 147 | Jammu and Kashmir | Rural | Interview | 59.9 | 4.7 |

| Preeti et al. | 2015 | 640 | 210 | Hyderabad | Urban | Unclear | 32.8 | 23.8 |

| Anitha et al. | 2015 | 61 | - | Udupi, Karnataka | Rural | Unclear | 34.0 | - |

| Varghese et al. | 2015 | 1522 | 1522 | Chennai, Tamil Nadu | Semi-urban | Self-administered | 14.7 | 3.6 |

| Walia et al. | 2015 | 111 | 88 | Chandigarh and Himachal Pradesh | Rural and urban | Interview | 79.3 | 2.7 |

| Tarhane et al. | 2015 | - | 100 | Nagpur, Maharashtra | Unclear | Self-administered | - | 1.0 |

| Mohanty et al. | 2016 | 118 | - | Berhampur, Odisha | Urban slums | Self-administered | 15.0 | - |

| Chadalawada et al. | 2016 | 150 | 109 | Vijayawada, Andhra Pradesh | Rural | Self-administered | 72.6 | 1.8 |

| Kansal et al. | 2016 | 590 | 174 | Chiraigaon, Varanasi | Rural | Interview | 29.4 | 1.4 |

| Seenivasan et al. | 2016 | 500 | 200 | North Chennai, Tamil nadu | Urban | Unclear | 40.0 | 4.5 |

| Kshirsagar et al. | 2016 | - | 190 | Maharashtra | Rural | Interview | - | 17.9 |

| Kanchan et al. | 2016 | 263 | - | Hyderabad | Rural and urban | Self-administered | 58.5 | - |

| Dudeja et al. | 2016 | 211 | 119 | Maharashtra | Urban slum | Self-administered | 56.4 | 8.5 |

| Anju et al. | 2016 | 436 | 244 | Perinthalmanna, Kerala | Rural | Self-administered | 55.9 | 1.5 |

| Ramachandra et al. | 2016 | 550 | - | Bangalore, Karnataka | Urban | Self-administered | 33.3 | - |

| Devi et al. | 2016 | 180 | 78 | Kancheepuram, Tamil Nadu | Rural | Self-administered | 43.3 | 12.8 |

| Taklikar et al. | 2016 | 50 | 50 | Kolkata, West Bengal | Urban slum | Interview | 58.0 | 12.0 |

| Nagaraj et al. | 2016 | 304 | 304 | Bangalore, Karnataka | Rural | Self-administered | 29.9 | 8.5 |

| Maji. | 2016 | 100 | - | Burdwan, West Bengal | Rural | Interview | 77.0 | - |

| Chauhan et al. | 2016 | - | 296 | Ahmadabad | Urban | Interview | - | 9.5 |

| Malhotra et al. | 2016 | 1800 | - | Uttar Pradesh | Rural | Interview | 43.0 | - |

| Krishnamurthy et al. | 2016 | 72 | - | Kolar, Karnataka | Rural | Self-administered | 36.2 | - |

| Singhal. | 2016 | 408 | - | Gurgaon, Haryana | Rural | Interview | 44.4 | - |

| Sarvade et al. | 2016 | 70 | 25 | Mumbai, Maharashtra | Urban | Self-administered | 36.0 | 20.0 |

| Sharma et al. | 2016 | 150 | - | Aroha, Haryana | Rural | Self-administered | 95.3 | - |

| Kusuma et al. | 2016 | 1500 | - | Mysore, Karnataka | Urban | Interview | 22.3 | - |

| Rokade et al. | 2016 | 324 | 183 | Solapur, Maharashtra | Urban | Interview | 56.4 | 14.2 |

| Bachloo et al. | 2016 | Rural: 159 Urban: 181 | Rural: 159 Urban: 181 | Ambala, Haryana | Rural and urban | Self-administered | Rural: 33.3 Urban: 41.5 | Rural: 10.7 Urban: 34.8 |

| Jitpure. | 2016 | - | 100 | Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh | Urban slums | Self-administered | - | 2.0 |

| Chauhan et al. | 2016 | 100 | - | Shimla, Himachal Pradesh | Rural | Interview | 86.0 | - |

| Dixit et al. | 2016 | 100 | - | Indore, Madhya Pradesh | Urban | Self-administered | 86.0 | - |

| Pal et al. | 2017 | 200 | - | Kolkata, West Bengal | Urban slum | Self-administered | 41.0 | - |

| Darivemula et al. | 2017 | 240 | 230 | Andhra Pradesh | Rural | Interview | 96.0 | 4.7 |

| Sarkar et al. | 2017 | - | 307 | Hooghly, West Bengal | Rural | Self-administered | - | 1.9 |

| Bedi et al. | 2017 | 192 | 192 | Ajmer, Rajasthan | Rural | Self-administered | 77.0 | 30.7 |

| Javalkar et al. | 2017 | 116 | - | Mangalore, Karnataka | Rural | Interview | 70.7 | - |

| Tuli et al. | 2017 | 197 | 197 | Ludhiana, Punjab | Rural | Interview | 16.7 | 1.5 |

| Singh et al. | 2017 | 2135 | - | Udham Singh Nagar, Uttarakhand | Unclear | Interview | 35.2 | - |

| Hakim et al. | 2017 | 500 | 271 | Jodhpur, Rajasthan | Urban | Interview | 54.2 | 12.5 |

| Agarwal et al. | 2017 | 250 | 181 | Sabarkantha, Gujarat | Rural | Interview | 35.6 | 2.0 |

| Mathiyalagen et al. | 2017 | 242 | - | Puducherry | Rural and urban | Interview | 48.3 | - |

| Shoor. | 2017 | 452 | - | Tumkur, Karnataka | Urban | Interview | 31.4 | - |

| Neelkanth et al. | 2017 | 197 | 197 | Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh | Unclear | Self-administered | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| Naithani. | 2017 | - | 1000 | Pauri, Uttarakhand | Rural and urban | Interview | - | 8.0 |

| Vandana et al. | 2017 | 200 | - | Ambala, Haryana | Rural | Unclear | 80.5 | - |

| Dabade et al. | 2017 | Rural: 107 Urban: 123 | - | Gulbarga, Karnataka | Rural and urban | Unclear | Rural: 63.5 Urban: 77.2 | - |

| Kapoor et al. | 2017 | 132 | 65 | Jammu | Rural | Interview | 49.2 | 3.0 |

| Hemapriya et al. | 2017 | 502 | - | Puducherry | Rural | Interview | 52.0 | - |

| Gandotra et al. | 2018 | 120 | 120 | Dehradun, Uttarakhand | Urban | Unclear | 62.5 | 8.3 |

| Deshpande et al. | 2018 | 100 | - | Karad, Maharashtra | Urban slum | Interview | 24.0 | - |

| Gupta et al. | 2018 | 212 | 50 | Etawah, Uttar Pradesh | Rural | Interview | 23.6 | 4.0 |

| Agarwal et al. | 2018 | 263 | 137 | Raipur, Chhattisgarh | Rural | Interview | 52.0 | 6.5 |

| Tarannum et al. | 2018 | 422 | 422 | Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh | Unclear | Unclear | 41.0 | 2.8 |

| Vashisht et al. | 2018 | - | 600 | Delhi | Unclear | Interview | - | 18.7 |

| Tiwari et al. | 2018 | 141 | - | Rajnandgaon, Chhattisgarh | Rural | Interview | 85.8 | - |

| Kakeri et al. | 2018 | - | 277 | Palghar, Maharashtra | Rural | Self-administered | - | 11.5 |

| Dharni. | 2018 | - | Rural: 50 Urban: 50 | Ludhiana, Punjab | Rural and urban | Interview | - | Rural: 8.0 Urban: 24.0 |

| Kavitha et al. | 2018 | 311 | - | Bangalore, Karnataka | Rural | Self-administered | 38.3 | - |

| Senapathi et al. | 2018 | - | 132 | Mangaluru, Karnataka | Rural | Interview | - | 3.7 |

| Gupta et al. | 2018 | Rural =150; Urban =150 | - | Kota, Rajasthan | Rural and urban | Self-administered | Rural: 59.3 Urban: 73.6 | - |

| Singh et al. | 2018 | 260 | - | Gurugram, Haryana | Unclear | Self-administered | 76.1 | - |

| Chauhan et al. | 2019 | 226 | - | South India | Rural | Self-administered | 35.8 | - |

| Aswathy et al. | 2019 | 432 | 432 | Thrissur, Kerala | Unclear | Self-administered | 71.3 | 6.3 |

| Rastogi et al. | 2019 | 250 | 187 | Delhi | Unclear | Interview | 40.0 | 2.4 |

| Sivakami et al. | 2019 | C* = 826 M* = 798 T* = 765 | C* = 927 M* = 837 T* = 800 | Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu | Unclear | Self-administered | C* = 45.5 M* = 42.7 T* = 33.2 | C* = 4.3 M* = 6.9 T* = 16.3 |

| Patel et al. | 2019 | 273 | 229 | Mandur, Goa | Rural | Self-administered | 83.9 | 4.8 |

| Nath et al. | 2019 | - | 250 | Kanyakumari district Tamil Nadu | Rural | Interview | - | 30.4 |

| Khatuja et al. | 2019 | 340 | 340 | Delhi | Urban slums | Interview | 48.0 | 11.3 |

| Pradhan et al. | 2019 | 165 | 165 | Cuttak, Odisha | Urban | Unclear | 59.4 | 2.4 |

| Sangra et al. | 2019 | 300 | - | Kathua, Jammu and Kashmir | Rural | Self-administered | 63.6 | - |

| Madhavi et al. | 2019 | 400 | 400 | Andhra Pradesh | Rural | Interview | 51.5 | 0.4 |

| Chajhlana et al. | 2019 | 69 | 69 | Hyderabad | Urban | Unclear | 28.1 | 1.4 |

| Budimelli et al. | 2019 | 200 | - | Guntur, Andhra Pradesh | Rural | Interview | 13.0 | - |

| Das et al. | 2019 | 110 | - | Jorhat, Assam | Urban slums | Interview | 42.2 | - |

| Sonowal et al. | 2019 | 150 | 74 | Dibrugarh, Assam | Urban slums | Interview | 49.3 | 4.1 |

| Jyothi et al. | 2019 | 200 | - | Bagalkot, Haryana | Urban | Interview | 71.0 | - |

| Choudhary et al. | 2019 | Rural: 215 Urban: 235 | - | Jodhpur, Rajasthan | Rural and urban | Self-administered | Rural: 59.1 Urban: 67.7 | - |

| Kamboj et al. | 2019 | 200 | 60 | Sirsa, Haryana | Rural | Self-administered | 30.0 | 15.0 |

| Gupta. | 2019 | 563 | - | Sambhal, Uttar Pradesh | Rural | Unclear | 86.0 | - |

| Parle et al. | 2019 | 600 | - | Raigad, Maharashtra | Rural | Self-administered | 55.2 | - |

| Kaur. | 2019 | - | 121 | Kapurthala, Punjab | Unclear | Unclear | - | 5.0 |

| Solvig et al. | 2019 | 288 | 189 | Bangalore, Karnataka | Rural and urban | Interview | 46.2 | 6.2 |

| Manuja et al. | 2019 | 257 | 220 | Mandya, Karnataka | Rural | Self-administered | 85.6 | 14.8 |

| Vaishampayan et al. | 2019 | 64 | - | Telangana | Unclear | Self-administered | 37.5 | - |

| Kalyani et al. | 2019 | 236 | 236 | Goa | Unclear | Self-administered | 55.0 | 7.0 |

| First Author | Year of Publication | Sample size | Location of the Study | Type of Area | Data Collection Method | Percent Schools with Disposal Facilities for Sanitary Products β | Percent Schools have Separate Toilets for Girls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sivakami et al. | 2019 | C*:927 girls M*:837 girls T*:800 girls (total: 53 schools) | Chhattisgarh Maharashtra Tamil Nadu | Unclear | Self-administered | C*:16.6 M*:16.7 T*:50.0 (average: 27.1) | C*:29.4 M*:20.3 T*:61.3 (average: 36.5) |

| UNICEF global baseline report. | 2018 | 377,929 school age population | India | Rural and urban | Secondary data | 62.0 | 73.0 |

| Periyasamy et al. | 2019 | 61 schools | Bengaluru | Urban | Interview | NA | 80.3 |

| Srivastava et al. | 2013 | 182 schools | Uttar Pradesh | Rural and urban | Interview | 51.0 | 52.0 |

| ASER report | 2018 | 17,730 schools | India | Rural | Survey | NA | 66.4 |

| Mehta. | 2005 | 7993 schools | Punjab | Rural and urban | Secondary data | NA | 66.8 |

| Tooley et al. | 2007 | 214 schools | East Delhi | Slums | Census and survey | NA | 44.9 |

| Zaidi S.M.I.A. | 2008 | 638,057 schools | India | Rural and urban | Secondary data | NA | 32.9 |

| Majra et al. | 2010 | 20 schools | Karnataka | Rural | Interview | NA | 60.0 |

| Joseph et al. | 2012 | 30 schools | Karnataka | Urban | Interview | NA | 73.3 |

| Rakesh et al. | 2014 | 78 schools | Kollam, Kerala | Unclear | Interview | NA | 30.7 |

| Kaur et al. | 2015 | 25 schools | Chandigarh | Rural and urban | Interview | NA | 60.0 |

| Santhya et al. | 2015 | 30 schools | Bihar | Rural and urban | Self-administered and interview | NA | 73.3 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharma, S.; Mehra, D.; Brusselaers, N.; Mehra, S. Menstrual Hygiene Preparedness Among Schools in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of System-and Policy-Level Actions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020647

Sharma S, Mehra D, Brusselaers N, Mehra S. Menstrual Hygiene Preparedness Among Schools in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of System-and Policy-Level Actions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(2):647. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020647

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Shantanu, Devika Mehra, Nele Brusselaers, and Sunil Mehra. 2020. "Menstrual Hygiene Preparedness Among Schools in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of System-and Policy-Level Actions" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 2: 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020647

APA StyleSharma, S., Mehra, D., Brusselaers, N., & Mehra, S. (2020). Menstrual Hygiene Preparedness Among Schools in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of System-and Policy-Level Actions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020647