Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents for Occupational Hepatitis C Infections in Germany

Abstract

1. Introduction

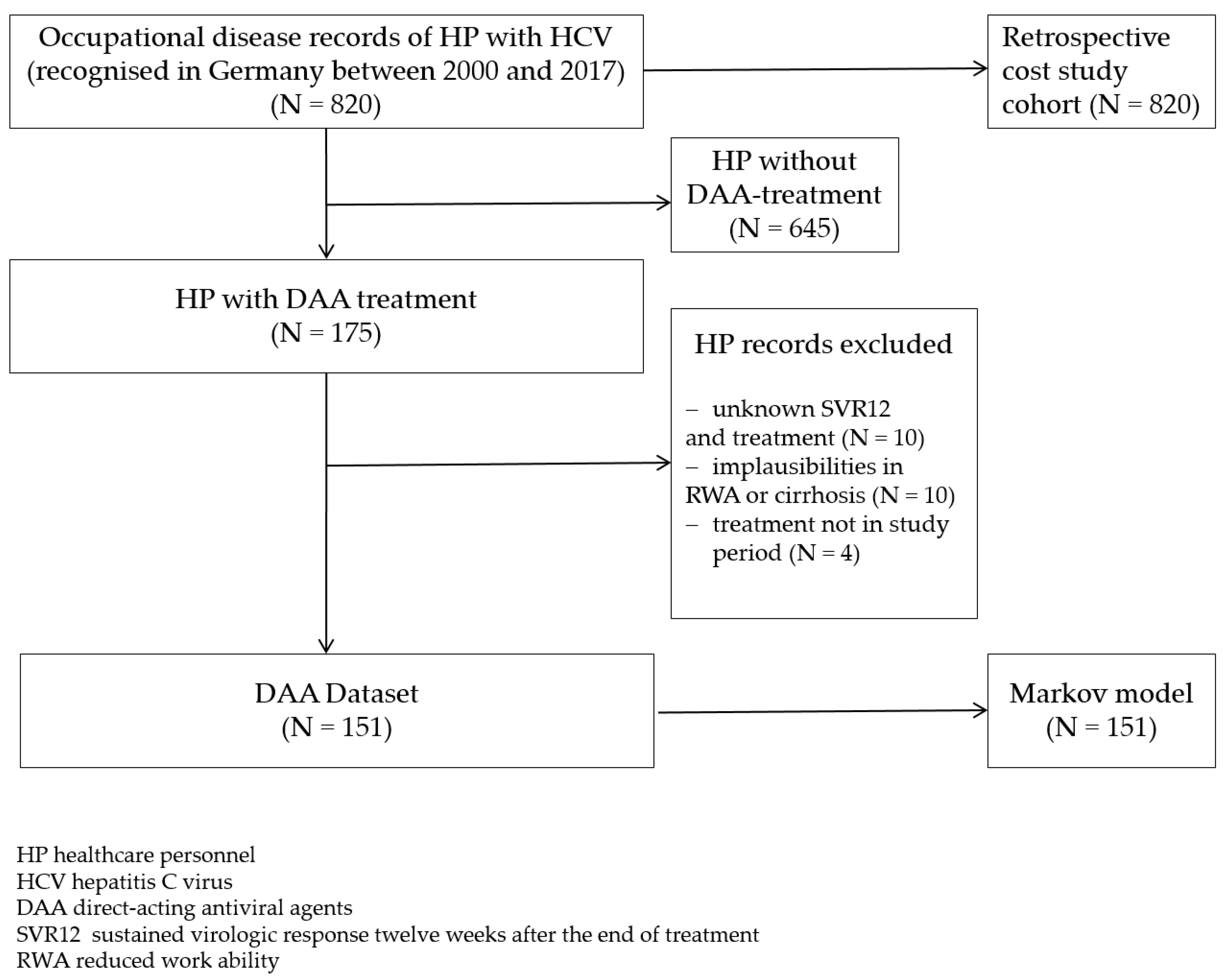

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

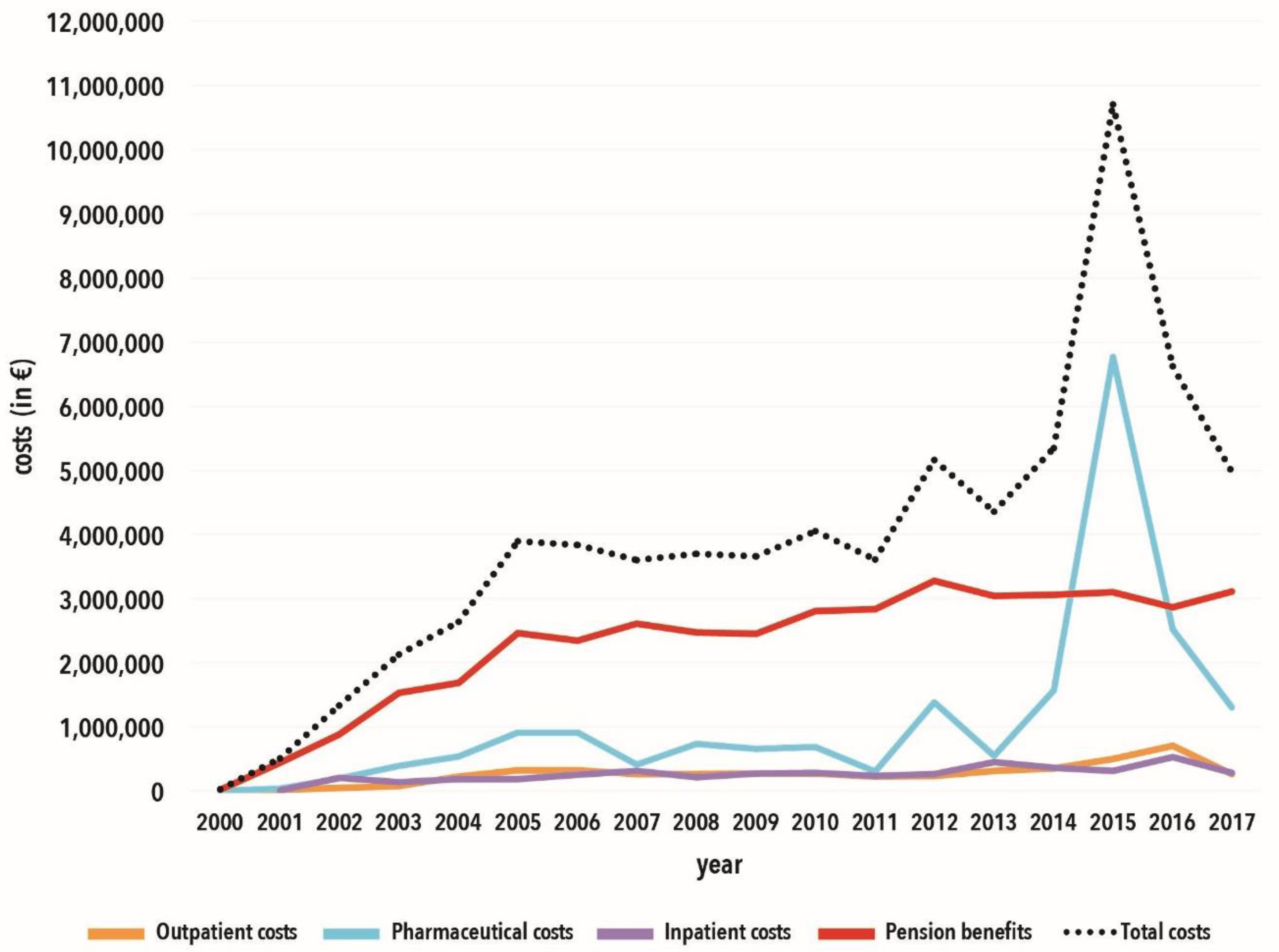

2.2. Retrospective Cost Study

2.3. Prospective Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA)

2.3.1. Assumptions for the SVR12 Rates

2.3.2. Assumptions for Health State Costs

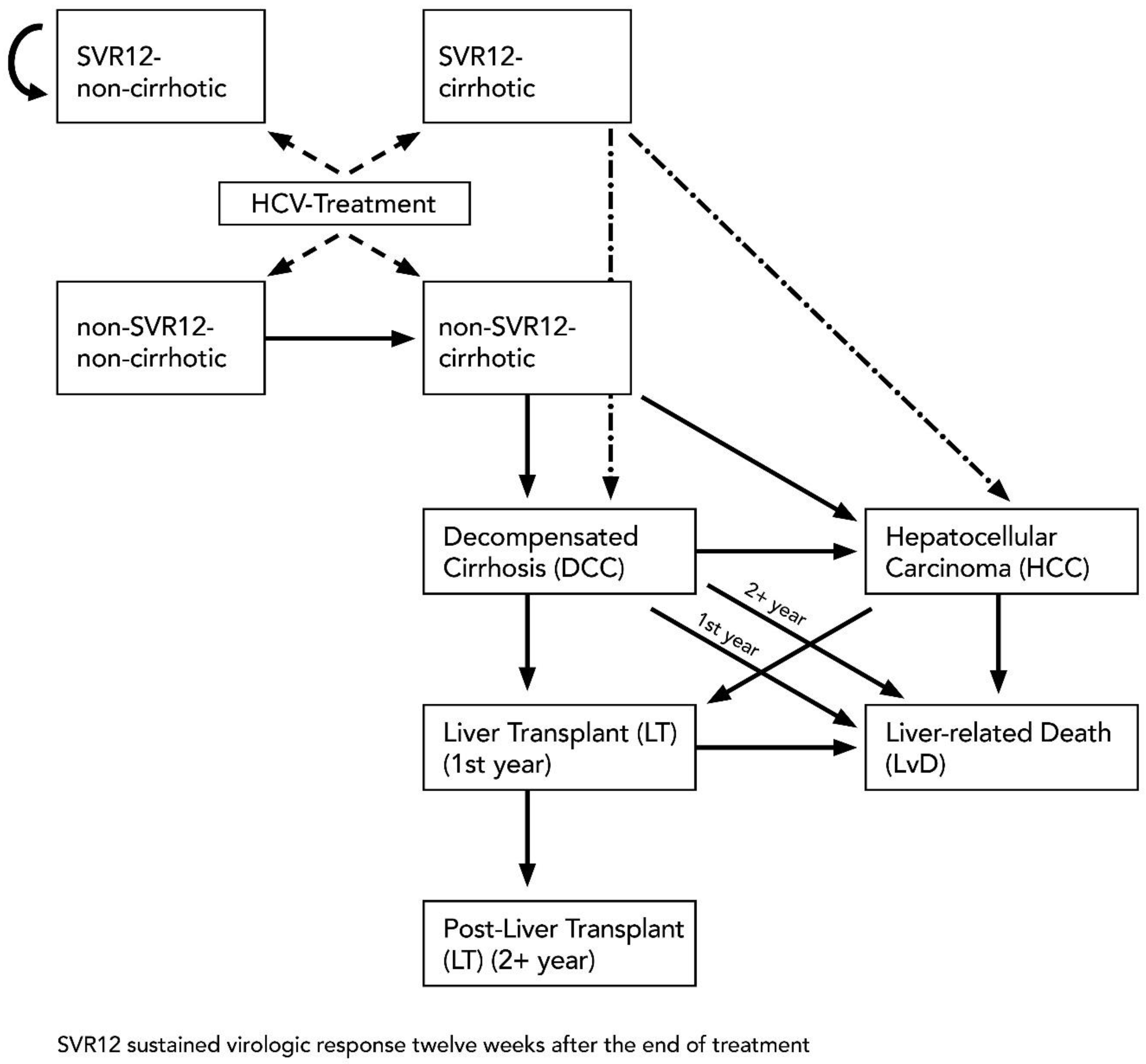

2.3.3. Model Structure

2.3.4. Liver-Related Mortality Rate

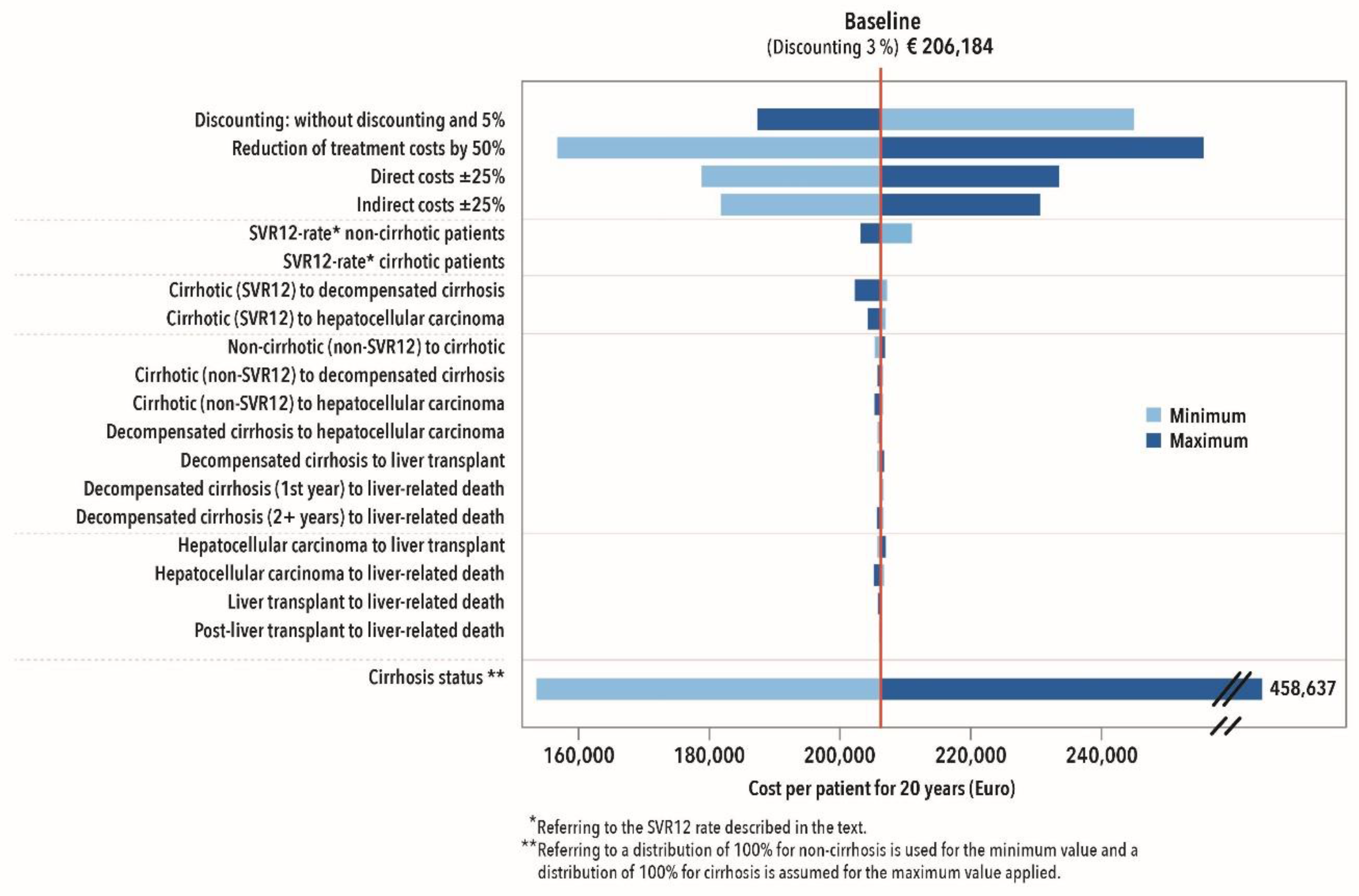

2.3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Retrospective Data Analysis

3.2. Prospective CEA—Markov Model

3.2.1. Description of Data Set

3.2.2. 20-Year Prediction

3.2.3. Cost Effectiveness

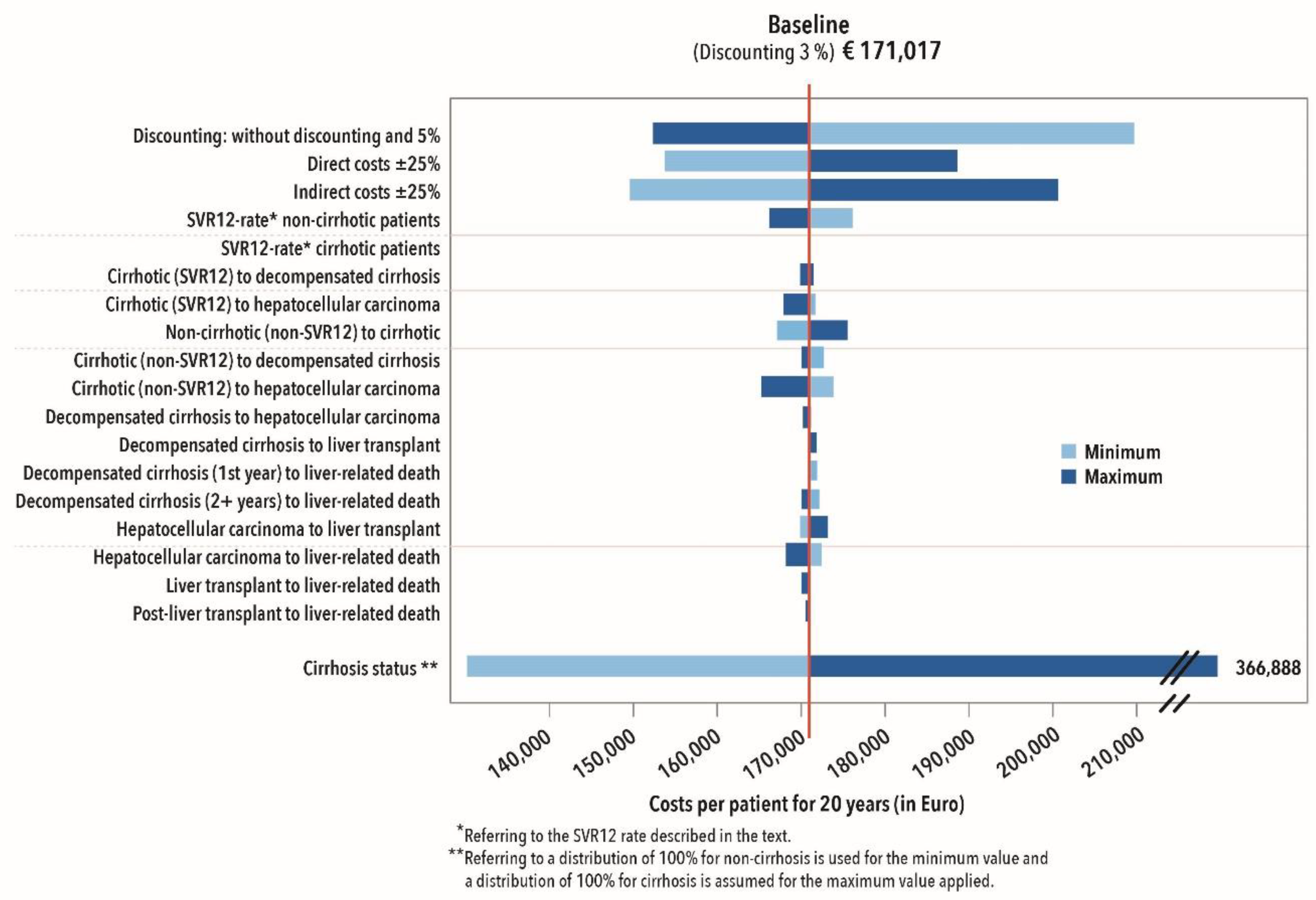

3.2.4. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Hepatitis Report 2017; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; p. 83, Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; Available online: http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/global-hepatitis-report2017/en/ (accessed on 6 August 2019).

- Robert Koch Institute. Infektionsepidemiologisches Jahrbuch meldepflichtiger Krankheiten für 2015; Robert Koch Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Singer, M.E.; Heshaam, M.M.; Henry, L.; Hunt, S. Impact of interferon free regimes on clinical and cost outcomes for chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 patients. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, C.M.; Sarrazin, C.; Zeuzem, S. Zukunft der antiviralen Therapie der chronischen Hepatitis, C. Pharm. Unserer Zeit 2011, 40, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrazin, C.; Zimmermann, T.; Berg, T.; Neumann, U.P.; Schirmacher, P.; Schmidt, H.; Spengler, U.; Timm, J.; Wedemeyer, H.; Wirth, S.; et al. S3 guideline “Prophylaxe, Diagnostik und Therapie der Hepatitis-C-Virus(HCV)-Infektion”. Z. Gastroenterol. 2018, 56, 756–838. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rosien, U.; Frederking, D.; Grandt, D. Chronische Hepatitis C: Umwälzungen in der Therapie durch die direkt antiviral wirkende Substanzen. Arzneiverordn. Prax. 2017, 44, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zachoval, R.; Jung, M.C. Chronic Hepatitis C—Therapeutic Options in 2016. MMW Fortschr. Med. 2016, 158, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, K.; Krauth, C.; Rossol, S.; Mauss, S.; Boeker, K.H.W.; Muller, T.; Klinker, H.; Pathil, A.; Heyne, R.; Stahmeyer, J.T. Outcomes and costs of treating hepatitis C patients with second-generation direct-acting antivirals: Results from the German Hepatitis C-Registry. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 31, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermann, C.; Wendeler, D.; Nienhaus, A. Hepatitis C in healthcare personnel: Secondary data analysis of therapies with direct-acting antiviral agents. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2018, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, R.; Kollan, C.; Ingiliz, P.; Mauss, S.; Schmidt, D.; Bremer, V. Real-world treatment for chronic hepatitis C infection in Germany: Analyses from drug prescription data, 2010–2015. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, T.; Jansen, P.L.; Sarrazin, C.; Vollmar, J.; Zeuzem, S. S3 guideline “Prophylaxe, Diagnostik und Therapie der Hepatitis-C-Virus (HCV)-Infektion”. Z. Gastroenterol. 2018, 56, e53–e115. [Google Scholar]

- Surjadi, M. Chronic Hepatitis C Screening, Evaluation, and Treatment Update in the Age of Direct-Acting Antivirals. Workplace Health Saf. 2018, 66, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nienhaus, A. Infections in Healthcare Workers in Germany—22-Year Time Trends. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulon, M.; Lisiak, B.; Wendeler, D.; Nienhaus, A. Unfallmeldungen zu Nadelstichverletzungen bei Beschäftigten in Krankenhäusern, Arztpraxen und Pflegeeinrichtungen. Das Gesundheitswesen 2018, 80, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nienhaus, A.; Kesavachandran, C.; Wendeler, D.; Haamann, F.; Dulon, M. Infectious diseases in healthcare workers—An analysis of the standardised data set of a German compensation board. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swart, E.; Bitzer, E.M.; Gothe, H.; Harling, M.; Hoffmann, F.; Horenkamp-Sonntag, D.; Maier, B.; March, S.; Petzold, T.; Röhrig, R.; et al. A Consensus German Reporting Standard for Secondary Data Analyses, Version 2 (STROSA-STandardisierte BerichtsROutine für SekundärdatenAnalysen). Gesundheitswesen 2016, 78, e145–e160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Husereau, D.; Drummond, M.; Petrou, S.; Carswell, C.; Moher, D.; Greenberg, D.; Augustovski, F.; Briggs, A.H.; Mauskopf, J.; Loder, E. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. Br. Med. J. 2013, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahmeyer, J.T.; Rossol, S.; Liersch, S.; Guerra, I.; Krauth, C. Cost-Effectiveness of Treating Hepatitis C with Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir in Germany. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afdhal, N.; Reddy, K.R.; Nelson, D.R.; Lawitz, E.; Gordon, S.C.; Schiff, E.; Nahass, R.; Ghalib, R.; Gitlin, N.; Herring, R.; et al. Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir for Previously Treated HCV Genotype 1 Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1483–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency Harvoni—Summary of Product Characteristics. 2014. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/harvoni#product-information-section (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Bacon, B.R.; Gordon, S.C.; Lawitz, E.; Marcellin, P.; Vierling, J.M.; Zeuzem, S.; Poordad, F.; Goodman, Z.D.; Sings, H.L.; Boparai, N.; et al. Boceprevir for Previously Treated Chronic HCV Genotype 1 Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency Victrelis—Summary for the Public. 2014. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/victrelis (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Stahmeyer, J.T.; Krauth, C.; Pfeiffer-Vornkahl, H.; Alshuth, U.; Hüppe, D.; Mauss, S.; Rossol, S. Costs and outcomes of treating chronic hepatitis C patients in routine care—Results from a nationwide multicenter trial. J. Viral Hepat. 2015, 23, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, U.; Sroczynski, G.; Rossol, S.; Wasem, J.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Kurth, B.M.; Manns, M.P.; McHutchison, J.G.; Wong, J.B. Cost effectiveness of peginterferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin versus interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Gut 2003, 52, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahmeyer, J.; Jacobs, S.; Rossol, S.; Heinrich Wedemeyer, H.; Wirth, D.; Bianic, F.; Krauth, C. Cost-effectiveness of Triple Therapy with Telaprevir for Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Patients in Germany. J. Health Econ. Outcomes Res. 2013, 1, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasem, J.; Sroczynski, G.; Aidelsburger, P.; Buchberger, B.; Hessel, F.; Conrads-Frank, A.; Peters-Blöchinger, A.; Kurth, B.M.; Wong, J.B.; Rossol, S.; et al. Gesundheitsökonomische Aspekte chronischer Infektionskrankheiten am Beispiel der chronischen Hepatitis, C. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2006, 49, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.J.; Khoo, A.L.; Lin, L.; Teng, M.; Koh, C.J.; Lim, S.G.; Lim, B.P.; Dan, Y.Y. Cost-effectiveness of strategy-based approach to treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 31, 1628–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Tanaka, A.; Eguchi, Y.; Henry, L.; Beckerman, R.; Mizokami, M. Treatment of hepatitis C virus leads to economic gains related to reduction in cases of hepatocellular carcinoma and decompensated cirrhosis in Japan. J. Viral Hepat. 2018, 25, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IQWIG (Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care). General Methods; Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care: Cologne, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grishchenko, M.; Grieve, R.D.; Sweeting, M.J.; De Angelis, D.; Thomson, B.J.; Ryder, S.D.; Irving, W.L. Cost-effectiveness of pegylated interferon and ribavirin for patients with chronic hepatitis C treated in routine clinical practice. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2009, 25, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvegnù, L.; Noventa, F.; Bernardinello, E.; Pontisso, P.; Gatta, A.; Alberti, A. Evidence for an association between the aetiology of cirrhosis and pattern of hepatocellular carcinoma development. Gut 2001, 48, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattovich, G.; Giustina, G.; Degos, F.; Tremolada, F.; Diodati, G.; Almasio, P.; Nevens, F.; Solinas, A.; Mura, D.; Brouwer, J.T.; et al. Morbidity and mortality in compensated cirrhosis type C: A retrospective follow-up study of 384 patients. Gastroenterology 1997, 112, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiovanni, A.; Prati, G.M.; Fasani, P.; Ronchi, G.; Romeo, R.; Manini, M.; Del Ninno, E.; Morabito, A.; Colombo, M. The natural history of compensated cirrhosis due to hepatitis C virus: A 17-year cohort study of 214 patients. Hepatology 2006, 43, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serfaty, L.; Aumaitre, H.; Chazouilleres, O.; Bonnand, A.M.; Rosmorduc, O.; Poupon, R.E.; Poupon, R. Determinants of outcome of compensated hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. Hepatology 1998, 27, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentilini, P.; Laffi, G.; La Villa, G.; Romanelli, R.G.; Buzzelli, G.; Casini-Raggi, V.; Melani, L.; Mazzanti, R.; Riccardi, D.; Pinzani, M.; et al. Long course and prognostic factors of virus-induced cirrhosis of the liver. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1997, 92, 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, A.-C.; Moucari, R.; Figueiredo-Mendes, C.; Ripault, M.-P.; Giuily, N.; Castelnau, C.; Boyer, N.; Asselah, T.; Martinot-Peignoux, M.; Maylin, S.; et al. Impact of peginterferon and ribavirin therapy on hepatocellular carcinoma: Incidence and survival in hepatitis C patients with advanced fibrosis. J. Hepatol. 2010, 52, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planas, R.; Balleste, B.; Alvarez, M.A.; Rivera, M.; Montoliu, S.; Galeras, J.A.; Santos, J.; Coll, S.; Morillas, R.M.; Sola, R. Natural history of decompensated hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. A study of 200 patients. J. Hepatol. 2004, 40, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuluvath, P.J.; Guidinger, M.K.; Fung, J.J.; Johnson, L.B.; Rayhill, S.C.; Pelletier, S.J. Liver transplantation in the United States, 1999–2008. Am. J. Transpl. 2010, 10, 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, G.L.; Alter, M.J.; El-Serag, H.; Poynard, T.; Jennings, L.W. Aging of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected persons in the United States: A multiple cohort model of HCV prevalence and disease progression. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, K.; Danchenko, N.; Gondek, K.; Shah, S.; Thompson, D. The burden of illness associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. J. Hepatol. 2009, 50, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saab, S.; Hunt, D.R.; Stone, M.A.; McClune, A.; Tong, M.J. Timing of hepatitis C antiviral therapy in patients with advanced liver disease: A decision analysis model. Liver Transpl. 2010, 16, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, R.A.; Roys, E.C.; Merion, R.M. Trends in organ donation and transplantation in the United States, 1999–2008. Am. J. Transpl. 2010, 10, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gissel, C.; Götz, G.; Mahlich, J.; Repp, H. Cost-effectiveness of Interferon-free therapy for Hepatitis C in Germany—An application of the efficiency frontier approach. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlin, R.; McCabe, C.; Hulme, C.; Hall, P.; Wright, J. Cost Effectiveness Modelling for Health Technology Assessment; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carrat, F.; Fontaine, H.; Dorival, C.; Simony, M.; Diallo, A.; Hezode, C.; De Ledinghen, V.; Larrey, D.; Haour, G.; Bronowicki, J.P.; et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C after direct-acting antiviral treatment: A prospective cohort study. Lancet 2019, 393, 1453–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Robert Koch Institute (RKI). GBE-Themenheft Hepatitis C. Gesundheitsberichtserstattung des Bundes. Gemeinsam getragen von RKI und Destatis; The Robert Koch Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Sadler, A. The Probabilistic Efficiency Frontier: A Value Assessment of Treatment Options in Hepatitis C. Das Gesundheitswesen 2019, 81, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chhatwal, J.; Kanwal, F.; Roberts, M.S.; Dunn, M.A. Cost-Effectiveness and Budget Impact of Hepatitis C Virus Treatment with Sofosbuvir and Ledipasvir in the United States. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermann, C.; Nienhaus, A.; Treszl, A. Quality of Life and Work Ability among Healthcare Personnel with Chronic Viral Hepatitis. Evaluation of the Inpatient Rehabilitation Program of the Wartenberg Clinic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wormann, B. The Treatment of Hepatitis C—An Introduction to the Use of New Medicines. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2017, 114, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reau, N.; Kwo, P.Y.; Rhee, S.; Brown, R.S., Jr.; Agarwal, K. Glecaprevir/Pibrentasvir Treatment in Liver or Kidney Transplant Patients with Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Hepatology 2018, 68, 1298–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeuzem, S.; Foster, G.R.; Wang, S.; Asatryan, A.; Gane, E.; Feld, J.J.; Asselah, T.; Bourliere, M.; Ruane, P.J.; Wedemeyer, H.; et al. Glecaprevir-Pibrentasvir for 8 or 12 Weeks in HCV Genotype 1 or 3 Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 354–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Health State | Base-Case Direct Costs (in €) | Base-Case Indirect Costs (in €) | Range (in %) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-cirrhotic (treatment year) | 64.518 | 6.555 | ±25 | o. c. |

| Cirrhotic (treatment year) entry 2 | 93.353 | 20.104 | ±25 | o. c. |

| Non-cirrhotic (SVR12) | 1.595 | 3.739 | ±25 | o. c. |

| Cirrhotic (SVR12) | 6.734 | 18.029 | ±25 | o. c. |

| Non-cirrhotic (non-SVR12) | 6.734 | 4.183 | ±25 | o. c. |

| Cirrhotic (non-SVR12) | 10.171 | 19.474 | ±25 | o. c. |

| Decompensated cirrhosis (1st year) | 9.768 | 19.474 | ±25 | [18,23,24,25,26] |

| Decompensated cirrhosis (2+ years) | 9.768 | 19.474 | ±25 | [18,23,24,25,26] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 24.096 | 19.474 | ±25% | [18,23,24,25,26] |

| Liver Transplant | 143.480 | 19.474 | ±25% | [18,23,24,25,26] |

| Post-liver Transplant | 20.751 | 19.474 | ±25% | [18,23,24,25,26] |

| Health State | Base-Case | Upper Range | Lower Range | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From: | To: | ||||

| Non-cirrhotic | Compensated cirrhosis | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.026 | [30] |

| Non-cirrhotic (SVR12) | SVR12 Non-cirrhotic | 1 | – | – | – |

| Cirrhotic | Decompensated cirrhosis | 0.029 | 0.010 | 0.039 | [31,32,33,34,35] |

| Cirrhotic | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.028 | 0.010 | 0.079 | [31,32,33,34,35] |

| Cirrhotic (SVR12) | Decompensated cirrhosis | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.036 | [36] |

| Cirrhotic (SVR12) | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.013 | [36] |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.068 | 0.030 | 0.083 | [37] |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | Liver transplant | 0.023 | 0.010 | 0.062 | [38,39] |

| Decompensated cirrhosis (1st year) | Liver-related death | 0.182 | 0.065 | 0.190 | [37] |

| Decompensated cirrhosis (2+ years) | Liver-related death | 0.112 | 0.065 | 0.190 | [37] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Liver transplant | 0.040 | 0.000 | 0.140 | [40,41] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Liver-related death | 0.427 | 0.330 | 0.860 | [32] |

| Liver Transplant | Liver-related death | 0.116 | 0.060 | 0.420 | [42] |

| Post-liver Transplant | Liver-related death | 0.044 | 0.024 | 0.110 | [42] |

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 151 | 100% |

| Gender | ||

| Woman | 118 | 78.1% |

| Men | 33 | 21.9% |

| Age group on therapy | ||

| ≤39 | 3 | 2.0% |

| 40–49 | 19 | 12.6% |

| 50–59 | 40 | 26.5% |

| >60 | 63 | 41.7% |

| Missing values | 26 | 17.2% |

| Professional activity | ||

| Physician | 23 | 15.2% |

| Nurse | 65 | 43.0% |

| Medical technical personnel | 2 | 1.3% |

| Medical assistant | 35 | 24.5% |

| Geriatric nurse | 14 | 9.3% |

| Social workers | 1 | 0.7% |

| Housekeeping | 5 | 3.3% |

| Administration and others | 4 | 2.6% |

| Side effects | ||

| None | 107 | 70.9% |

| Headaches, nausea, sleep disorder | 25 | 16.6% |

| Skin reactions | 3 | 2.0% |

| Depression, anxiety | 3 | 2.0% |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 3 | 2.0% |

| Others | 10 | 6.6% |

| SVR12 | ||

| Yes | 140 | 92.7% |

| No | 5 | 3.3% |

| Missing values | 6 | 4.0% |

| RWA before therapy with DAAs | ||

| <50 | 116 | 76.82% |

| ≥50 | 35 | 23.18% |

| RWA after therapy with DAAs | ||

| <50 | 124 | 82.19% |

| ≥50 | 27 | 17.81% |

| Discounted Costs (in €), SVR12 Rates and ICER (€/SVR12 Percentage Point) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Costs (in €) | SVR12 Percentage Point | ICER (€/SVR12 Percentage Point) | |

| Triple Therapies | 171.017 | 49.85 * | – |

| DAA Therapies | 206.184 | 95.75 ** | €766.19/SVR12 Percentage Point |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Runge, M.; Krensel, M.; Westermann, C.; Bindl, D.; Nagels, K.; Augustin, M.; Nienhaus, A. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents for Occupational Hepatitis C Infections in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020440

Runge M, Krensel M, Westermann C, Bindl D, Nagels K, Augustin M, Nienhaus A. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents for Occupational Hepatitis C Infections in Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(2):440. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020440

Chicago/Turabian StyleRunge, Melanie, Magdalene Krensel, Claudia Westermann, Dominik Bindl, Klaus Nagels, Matthias Augustin, and Albert Nienhaus. 2020. "Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents for Occupational Hepatitis C Infections in Germany" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 2: 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020440

APA StyleRunge, M., Krensel, M., Westermann, C., Bindl, D., Nagels, K., Augustin, M., & Nienhaus, A. (2020). Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents for Occupational Hepatitis C Infections in Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020440