Gender Informed or Gender Ignored? Opportunities for Gender Transformative Approaches in Brief Alcohol Interventions on College Campuses

Abstract

1. Introduction

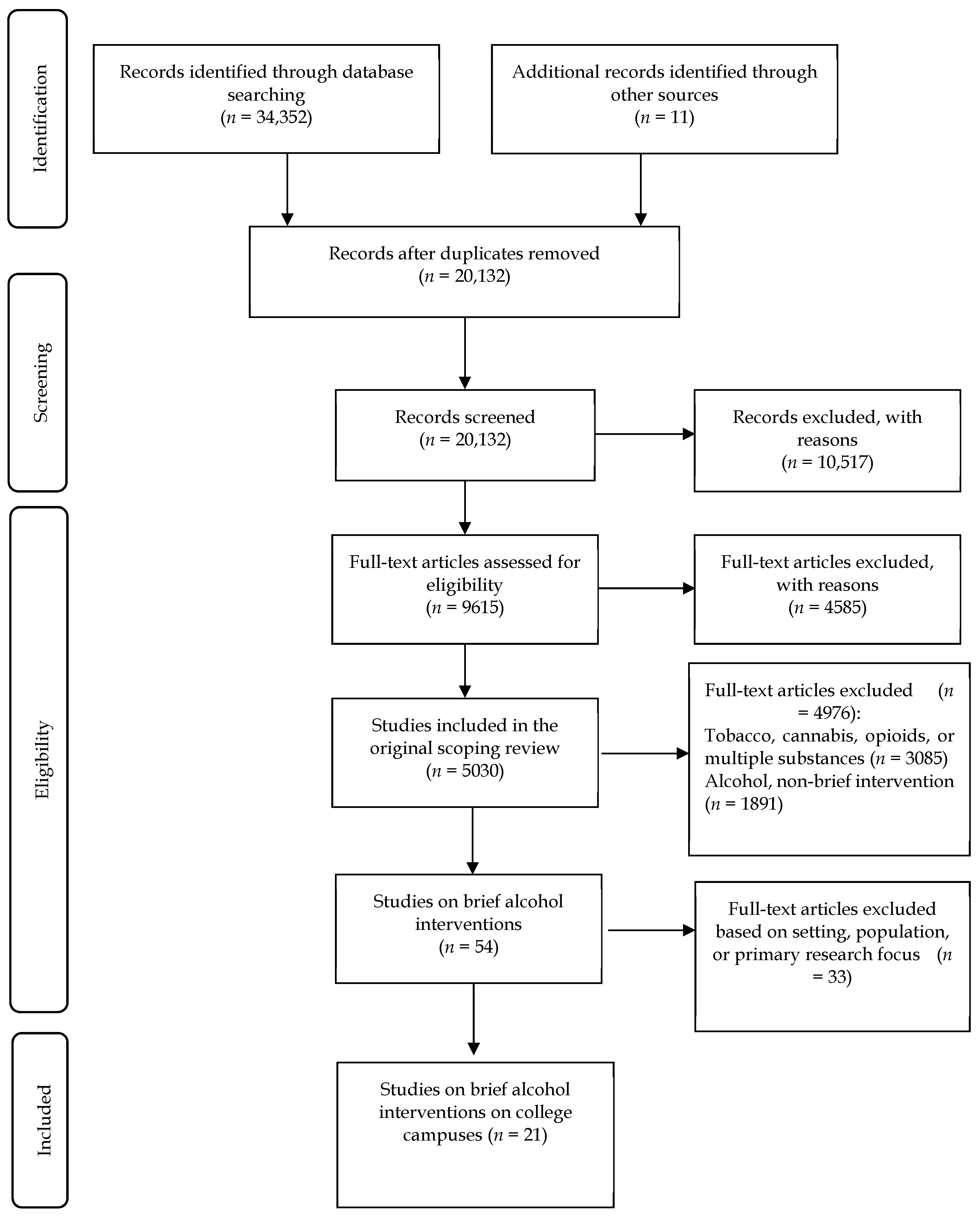

2. Materials and Methods

- How do sex- and gender-related factors impact (a) patterns of use; (b) health effects of; and (c) prevention, treatment, and harm reduction outcomes for the four substances?

- What harm reduction, health promotion, prevention, and treatment interventions and programs are available that include sex, gender, and gender-transformative elements, and how effective are these interventions in addressing opioid, alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis use?

3. Results

3.1. Interventions Using Social Norms and Personalized Normative Feedback

3.2. Technology-Based Interventions

3.3. Dual Interventions

3.4. Mail-In Interventions

3.5. Gender Inclusion and Considerations

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Considerations

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Larimer, M.; Cronce, J.M.; Lee, C.M.; Kilmer, J.R. Brief intervention in college settings. Alcohol Res. Health 2004, 28, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Malley, P.M.; Johnston, L.D. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. J. Stud. Alcohol 2002, 63, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sher, K.J.; Rutledge, P.C. Heavy drinking across the transition to college: Predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addict. Behav. 2007, 32, 819–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Reducing the Harms Related to Alcohol on College Campuses; Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Heavy Drinking, 2016; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017.

- Thompson, M.P.; Spitler, H.; McCoy, T.P.; Marra, L.; Sutfin, E.L.; Rhodes, S.D.; Brown, C. The moderating role of gender in the prospective associations between expectancies and alcohol-related negative consequences among college students. Subst. Use Misuse 2009, 44, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- LaBrie, J.W.; Thompson, A.D.; Huchting, K.; Lac, A.; Buckley, K. A group Motivational Interviewing intervention reduces drinking and alcohol-related negative consequences in adjudicated college women. Addict. Behav. 2007, 32, 2549–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuntsche, E.; Muller, S. Why do young people start drinking? Motives for first-time alcohol consumption and links to risky drinking in early adolescence. Eur. Addict. Res. 2012, 18, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilson, E.C.; Gilmore, A.K.; Pinsky, H.T.; Shepard, M.E.; Lewis, M.A.; George, W.H. The Use of Drinking and Sexual Assault Protective Behavioral Strategies: Associations With Sexual Victimization and Revictimization Among College Women. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 33, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, K.S.; Carey, K.B.; Lao, K.; Luciano, M. Injunctive norms for alcohol-related consequences and protective behavioral strategies: Effects of gender and year in school. Addict. Behav. 2011, 36, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Poole, N.; Greaves, L.; Hemsing, N. New Terrain: Tools to Integrate Trauma and Gender Informed Responses into Substance Use Practice and Policy; Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pederson, A.; Greaves, L.; Poole, N. Gender-transformative health promotion for women: A framework for action. Health Promot. Int. 2015, 30, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larimer, M.E.; Cronce, J.M. Identification, prevention and treatment: A review of individual-focused strategies to reduce problematic alcohol consumption by college students. J. Stud. Alcohol Suppl. 2002, 14, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathoo, T.; Poole, N.; Wolfson, L.; Schmidt, R.; Hemsing, N.; Gelb, K. Doorways to Conversation: Brief Intervention on Substance Use with Girls and Women; Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nathoo, T.; Wolfson, L.; Gelb, K.; Poole, N. New approaches to brief intervention on substance use during pregnancy. Can. J. Midwifery Res. Pract. 2019, 18, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Huh, D.; Mun, E.Y.; Larimer, M.E.; White, H.R.; Ray, A.E.; Rhew, I.C.; Kim, S.Y.; Jiao, Y.; Atkins, D.C. Brief motivational interventions for college student drinking may not be as powerful as we think: An individual participant-level data meta-analysis. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2015, 39, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimeff, L.A.; Baer, J.S.; Kivlahan, D.R.; Marlatt, G.A. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A Harm Reduction Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behaviour; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie, J.W.; Lac, A.; Kenney, S.R.; Mirza, T. Protective behavioral strategies mediate the effect of drinking motives on alcohol use among heavy drinking college students: Gender and race differences. Addict. Behav. 2011, 36, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsing, N.; Greaves, L. Gender norms, roles, and relations and cannabis use patterns: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.J.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Baldini Soares, C. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudt, H.M.; Van Mossel, C.; Scott, S.J. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arskey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.A.; Neighbors, C. Optimizing personalized normative feedback: The use of gender-specific referents. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2007, 68, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, A.K.; Bountress, K.E. Reducing drinking to cope among heavy episodic drinking college women: Secondary outcomes of a web-based combined alcohol use and sexual assault risk reduction intervention. Addict. Behav. 2016, 61, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmore, A.K.; Lewis, M.A.; George, W.H. A randomized controlled trial targeting alcohol use and sexual assault risk among college women at high risk for victimization. Behav. Res. Ther. 2015, 74, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, K.; Burgess, J.; MacNevin, P.D. An Evaluation of e-CHECKUP TO GO in Canada: The Mediating Role of Changes in Social Norm Misperceptions. Subst. Use Misuse 2018, 53, 1849–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, M.A.; Neighbors, C.; Oster-Aaland, L.; Kirkeby, B.S.; Larimer, M.E. Indicated prevention for incoming freshmen: Personalized normative feedback and high-risk drinking. Addict. Behav. 2007, 32, 2495–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaysen, D.L.; Lee, C.M.; Labrie, J.W.; Tollison, S.J. Readiness to change drinking behavior in female college students. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2009, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, S.R.; Napper, L.E.; LaBrie, J.W.; Martens, M.P. Examining the Efficacy of a Brief Group Protective Behavioral Strategies Skills Training Alcohol Intervention with College Women. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014, 28, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBrie, J.W.; Huchting, K.; Tawalbeh, S.; Pedersen, E.R.; Thompson, A.D.; Shelesky, K.; Larimer, M.; Neighbors, C. A randomized motivational enhancement prevention group reduces drinking and alcohol consequences in first-year college women. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2008, 22, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBrie, J.W.; Cail, J.; Pedersen, E.R.; Migliuri, S. Reducing alcohol risk in adjudicated male college students: Further validation of a group motivational enhancement intervention. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abus. 2011, 20, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lojewski, R.; Rotunda, R.J.; Arruda, J.E. Personalized normative feedback to reduce drinking among college students: A social norms intervention examining gender-based versus standard feedback. J. Alcohol Drug Educ. 2010, 54, 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Murgraff, V.; Abraham, C.; McDermott, M. Reducing friday alcohol consumption among moderate, women drinkers: Evaluation of a brief evidence-based intervention. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007, 42, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neighbors, C.; Pedersen, E.R.; Kaysen, D.; Kulesza, M.; Walter, T. What Should We Do When Participants Report Dangerous Drinking? The Impact of Personalized Letters Versus General Pamphlets as a Function of Sex and Controlled Orientation. Ethics Behav. 2012, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bountress, K.E.; Metzger, I.W.; Maples-Keller, J.L.; Gilmore, A.K. Reducing sexual risk behaviors: Secondary analyses from a randomized controlled trial of a brief web-based alcohol intervention for underage, heavy episodic drinking college women. Addict. Res. Theory 2017, 25, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajecki, M.; Berman, A.H.; Sinadinovic, K.; Rosendahl, I.; Andersson, C. Mobile phone brief intervention applications for risky alcohol use among university students: A randomized controlled study. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2014, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suffoletto, B.; Merrill, J.E.; Chung, T.; Kristan, J.; Vanek, M.; Clark, D.B. A text message program as a booster to in-person brief interventions for mandated college students to prevent weekend binge drinking. J. Am. Coll. Health 2016, 64, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton-Sherrod, M.; Morgan-Lopez, A.A.; Brown, J.M.; McMillen, B.A.; Cowell, A. Incapacitated sexual violence involving alcohol among college women: The impact of a brief drinking intervention. Violence Women 2011, 17, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBrie, J.W.; Thompson, A.D.; Ferraiolo, P.; Garcia, J.A.; Huchting, K.; Shelesky, K. The differential impact of relational health on alcohol consumption and consequences in first year college women. Addict. Behav. 2008, 33, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brahms, E.; Ahl, M.; Reed, E.; Amaro, H. Effects of an alcohol intervention on drinking among female college students with and without a recent history of sexual violence. Addict. Behav. 2011, 36, 1325–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBrie, J.W.; Huchting, K.K.; Lac, A.; Tawalbeh, S.; Thompson, A.D.; Larimer, M.E. Preventing risky drinking in first-year college women: Further validation of a female-specific motivational-enhancement group intervention. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2009, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, J.E.; Reid, A.E.; Carey, M.P.; Carey, K.B. Gender and depression moderate response to brief motivational intervention for alcohol misuse among college students. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 984–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Berger, J.B. Women’s ways of drinking: College women, high-risk alcohol use, and negative consequences. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2010, 51, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, H.; Chen, S.-P.; Krupa, T.; Narain, T.; Horgan, S.; Dobson, K.; Stewart, S. The caring campus project overview. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2019, 37, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Student Wellness Centre. Alcohol 101. Available online: https://students.usask.ca/articles/alcohol.php (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Saskatchewan Prevention Institute. Blindsided by the Alcohol Industry? Saskatchewan Prevention Institute: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Sex, Gender, and Equity Analyses; Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Status of Women Canada. Government of Canada’s Gender-Based Analysis Plus Approach. Available online: https://cfc-swc.gc.ca/gba-acs/approach-approche-en.html (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Sex, Gender, and Health Research. Available online: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50833.html (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- European Gender Medicine. Final Report Summary—EUGENMED (European Gender Medicine Network); Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women’s Health. Sex & Gender. Available online: https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sex-gender (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Kelley-Baker, T.; Johnson, M.B.; Romano, E.; Mumford, E.A.; Miller, B.A. Preventing victimization among young women: The SafeNights intervention. Am. J. Health Stud. 2011, 26, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grossbard, J.R.; Mastroleo, N.R.; Geisner, I.M.; Atkins, D.; Ray, A.E.; Kilmer, J.R.; Mallett, K.; Larimer, M.E.; Turrisi, R. Drinking norms, readiness to change, and gender as moderators of a combined alcohol intervention for first-year college students. Addict. Behav. 2016, 52, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrie, J.; Lamb, T.; Pedersen, E. Changes in drinking patterns across the transition to college among first-year college males. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abus. 2008, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starosta, A.J.; Cranston, E.; Earleywine, M. Safer sex in a digital world: A Web-based motivational enhancement intervention to increase condom use among college women. J. Am. Coll. Health 2016, 64, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Location | Research Aim | Participants | Measures (Excluding Baseline Demographic) | Intervention Overview | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bountress et al. 2017 [38] | United States | To examine the effects of sexual assault history on alcohol and sexual risk behaviours (SRBs) and the effect of a web-based alcohol BI to reduce alcohol use and SRBs | n = 160 female college students, 18–20 years old (yo), who engaged in past-month HED | Questions on number of male sexual partners, and HED occasions; Sexual Assertiveness Survey (Pregnancy STD Prevention Subscale); revised Childhood Sexual Abuse (CSA) questionnaire; and Sexual Experiences Survey (SES) | Web-based intervention using personalized and gender-specific feedback, including protective strategies | Increased levels of condom use assertiveness; no effect on number of sexual partners; higher alcohol use among individuals with adolescent sexual assault histories |

| Brahms et al., 2011 [43] | United States | To analyze the effects of sexual violence on Brief Alcohol Screen in College Students (BASICS) outcomes | n = 351 female college students reporting significant alcohol and/or drug use | Sexual Risk Behaviour Questionnaire; Brief Symptom Inventory; Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ); and Quantity Frequency Scale | Two 45–60-min BASICS sessions | Reduced alcohol consumption; reduced coping skills in women who experienced sexual violence, but not with women who had not experienced sexual violence |

| Clinton-Sherrod et al., 2011 [41] | United States | To examine the effect of sexual victimization on an alcohol brief intervention | n = 229 first year, female college students | Prior victimization measures; questions on past-month drinks and drinking-occasions; Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test; Stages of Change Readiness; and Treatment Eagerness Scale and Ambivalence and Recognition subscales | Four intervention conditions: (a) MI only included exploring alcohol-related consequences and change readiness; (b) feedback only included personalized feedback norms, estimated level of risk, a list of relevant resources; (c) MI with feedback (MIFB) which included strategies from both conditions; and d) control | Ambivalence to change was associated with sexual coercion; decreased alcohol use for women in MI and MIFB conditions; women with history of sexual violence in MIFB condition had steeper declines in three-month violence outcomes compared to women without a history of sexual violence |

| Gajecki et al., 2014 [39] | Sweden | To explore the effect of two smartphone alcohol BI on university students with established levels of risky alcohol consumption | n = 1929 university student union members with Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) scores ≥ 6 for women and ≥ 8 for men and a smartphone | DDQ; and AUDIT | Two smartphone apps: (a) Promillekoll (Check Your BAC) included real time e-Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) and protective and behavioural strategies; (b) PartyPlanner included event simulation, skillfulness and behavioural strategies, and pre-party simulated and real-time BAC. | Increased drinking frequency among male Promillekoll users |

| Gilmore et al., 2015 [28] | United States | To assess the efficacy of a web-based alcohol BI, sexual assault risk reduction (SARR) intervention, or combined intervention reducing alcohol use and SRBs | n = 264 female college students, 18–20 yo, who engaged in past-month HED | Questions on alcohol use during sexual experiences, HED, and estimation of sexual violence; revised Dating Self-Protection against Rape Scale; DDQ; SES; Drinking Norms Rating Form; and Protective Behavioural Strategies Surveys (PBSS) | Four intervention conditions: (a) SARR only included sexual assault education and resistance strategies; (b) alcohol only included alcohol psychoeducation, personalized feedback, and PNF; (c) combined intervention which included strategies from both conditions; and (d) control | Reduced alcohol-related sexual violence among the combined condition; reduced HED among women with more severe sexual violence histories in the combined condition; increased perceived likelihood of alcohol-related sexual violence in the SARR condition |

| Gilmore et al., 2016 [27] | United States | To assess the efficacy of a web-based alcohol and SARR intervention on female college students who are drinking as a coping mechanism | n = 264 female college students, 18–20 yo, who engaged in past-month HED | Questions on HED and Greek affiliation; SES; Readiness to Change questionnaire for brief interventions; and Drinking Motives Questionnaire—Revised Short-Form | See Gilmore et al., 2015 | Increased readiness to change among individuals with severe sexual assault histories; reduced drinking to cope for individuals with HED in the combined intervention; no effects on alcohol or SARR interventions on drinking to cope |

| Kaysen et al., 2009 [31] | United States | To explore the effect MI on participants’ readiness to change (RTC) and drinking behaviours | n = 182 first year female college students who consumed alcohol at least once in the previous month | Questions on intention to drink; 3-month Timeline Followback (TLFB)); and Readiness to Change Ruler | Two-hour group sessions with 8–12 participants including individual TLFB assessment, discussion on alcohol expectancies and positive and negative consequences, normative feedback, sex-specific considerations, and personal goal setting | Correlation between missing to report and increased drinking; correlation between RTC and decreased future drinking; increased RTC among intervention group |

| Kenney et al., 2014 [32] | United States | To increase protective behavioural strategies (PBS) through a cognitive behaviour skills intervention focusing on decreasing risky drinking and related consequences | n = 226 first year female college students who engaged in past-month HED | Online survey on health behaviours and beliefs related to alcohol and mental health; PBSS and Strategy Questionnaire; DDQ; Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI); Beck Anxiety Inventory; and Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale | Two-hour group sessions with 8–12 participants using cognitive behavioural skills to discuss alcohol-related consequences, skills to use PBS, and PBS-related goals. Personalized PBS feedback sheets provided to participants with past-month PBS. | Increased PBS at 1- and 6-month follow up; higher PBS among high anxiety participants in intervention group |

| LaBrie et al., 2007 [7] | United States | To explore female-specific reasons for drinking and the impact of a group brief motivational intervention (BMI) on alcohol consumption and alcohol-related negative consequences | n = 115 female college students who were first time offenders of campus alcohol policies | Questions on alcohol use over the past month; Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ) and Conformity, Coping, Enhancement, and Social Motives subscales; and RAPI | Two-hour group sessions with 8–12 participants using cognitive behavioural skills to discuss alcohol-related consequences and skills to use PBS. Twelve follow-up diaries were used to calculate behavioural outcomes and to assess alcohol-related consequences. | Decreased drinks per month, number of drinking days per month, average drinks, and maximum drinks; significant reductions in all alcohol use behaviours except for number of drinking days per month |

| LaBrie et al., 2008 [33] | United States | To examine the effect of a single BMI with a focus on female-specific reasons for drinking | n = 220 first year female college students | DMQ and Conformity, Coping, Enhancement, and Social Motives subscales; TLFB; and RAPI | See Kaysen et al., 2009 | Reduced binge drinking episodes and alcohol related consequences; most significant decreases with women with stronger social and enhancement drinking motives |

| LaBrie et al., 2008 [42] | United States | To assess the role of relational health in alcohol consumption and alcohol-related consequences | n = 214 first year female college students | RAPI; TLFB; Relational Health Indices; and DMQ and Conformity, Coping, Enhancement, and Social Motives subscales | Group session to learn about and discuss alcohol-related consequences | Women with stronger peer relationships and community connection drank more but experienced fewer alcohol-related consequences |

| LaBrie et al., 2009 [44] | United States | To explore the efficacy of a group BMI on female alcohol consumption | n = 285 first year female college students | TLFB; DMQ and Conformity, Coping, Enhancement, and Social Motives subscales; and RAPI | See Kaysen et al., 2009 | Reduced drinks per week, maximum drinks, and heavy episodic events; women with strong social drinking motives were more likely to reduce their drinks per week compared to those with weak social motives; results no longer significant at 6-month follow-up |

| LaBrie et al., 2010 [34] | United States | To validate the effectiveness of a group BMI intervention on adjudicated male students, and develop a gender-specific intervention for men | n = 230 male college students who violated campus alcohol policies | Questions on drinking behaviours and motivations; TLFB; and DMQ and Conformity, Coping, Enhancement, and Social Motives subscales | One 60–75-min group session with 8 to 15 participants to discuss their school sanctions, perceived drinking norms, alcohol-related consequences, and skills to respond to adverse consequences. Twelve follow-up diaries were used to calculate behavioural outcomes and to assess alcohol-related consequences. | Decreased drinks per month, RAPI scores, and recidivism rates |

| Lewis et al., 2007 [26] | United States | To evaluate if gender specificity in computer-generated personalized normative feedback (PNF) intervention would shift alcohol norms and reduce alcohol consumption | n = 165 college students who engaged in past-month HED | Drinking Norms Rating Form (and the gender-specific version); Alcohol Consumption Inventory; DDQ; Quantity Frequency Scale; and revised Collective Self-Esteem Scale | Three intervention groups: (a) gender-specific PNF and (b) gender-neutral PNF, which included with 1–2 min-computer feedback and printout on personal drinking, perceptions of student drinking, and drinking norms; and (c) control | Reduced drinking among both PNF conditions; gender-specific PNF was more effective on reducing drinking among women who strongly identified with their gender; higher gender-specific normative misperceptions among men with medium effect sizes for women |

| Lewis et al., 2007 [30] | United States | To determine if a gender-specific computer-generated PNF intervention would be more effective than gender-neutral PNF intervention in shifting alcohol norms and reducing alcohol consumption | n = 209 first year college students who engaged in past-month HED | Questions on past-month alcohol consumption, DDQ; and Drinking Norms Rating Form (and the gender-specific version) | Three intervention groups: (a) gender-specific PNF and (b) gender-neutral PNF, which included with 1–2-min computer feedback and printout on personal drinking, perceptions of student drinking, and drinking norms; and (c) control | Freshmen and opposite-sex norms were not related to drinks per week; same-sex freshmen norms were associated with increased rinks per week; reduced drinks in both intervention groups but with more consistent changes among the gender-specific PNF |

| Lojewski et al., 2010 [35] | United States | To determine if gender-specific normative feedback will be more effective that a gender-neutral intervention in decreasing alcohol use misperceptions on campus and reducing alcohol consumption | n = 246 college students | Drinking Norms Rating Form; AUDIT; College Alcohol Problem Scale-revised | Three intervention groups: (a) gender-specific PNF and (b) gender-neutral PNF, where participants were provided normative feedback and detailed representation of norms and drinking behaviours; and (c) control | No gender interaction on perceptions of drinking; age was negatively correlated with peer drinking perceptions and reduced alcohol per episode |

| Merrill et al., 2014 [45] | United States | To determine the effect of gender and depression on the efficacy of an alcohol BI | n = 330 college freshmen, sophomores or juniors, 18–25 yo that engaged in ≥1 episode of past-week HED or ≥4 episodes of past-month HED | Questions on Greek affiliation; Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; DDQ; and RAPI | Five intervention groups stratified by gender: (a) TLFB interview; (b) TLFB control; (c) control; (d) basic BMI; and (e) BMI with decisional other | BMI conditions significantly reduced weekly drinking and heavy frequency among men with high depression scores and women with low depression scores; association with higher levels of depression and alcohol-related consequences |

| Murgraff et al., 2007 [36] | United Kingdom | To evaluate the efficacy of a leaflet intervention in reducing Friday and Saturday risky single-occasion drinking | n = 347 college students who engaged in moderate alcohol consumption | Questions on standard drink consumption and to measure cognitions on intention, self-efficacy, and action-specific self-efficacy | Leaflet with recommended daily limits, strategies for reduced alcohol consumption, and implementation intention prompts | Increased self-efficacy on actions to reduce alcohol consumption for men; reduced risky single-occasion drinking for women |

| Neighbors et al., 2012 [37] | United States | To evaluate the efficacy of a pamphlet and personalized letter on reducing peak alcohol consumption | n = 818 college students who engaged in past-month HED | Alcohol Frequency-Quantity Questionnaire | Two intervention groups: (a) personalized letter with their reported BAC, peak drinking occasions, and information about alcohol and other substance use and available resources; and (b) non-personalized letter including information about alcohol and other substance use, available resources, and a BAC calculator | Personalized letter reduced peak BAC in women and students with higher alcohol use |

| Suffoletto et al., 2016 [40] | United States | To describe the impact of a six-week text-message intervention on weekend drinking and binge drinking episodes | n = 224 college students who violated campus alcohol policies | Questions on alcohol consumption and willingness to commit to a drinking limit | Six-week text message intervention that collected data on Thursday and Sunday to understand their weekend drinking patterns, commit to weekend drinking limits, and change attitudes and perceived norms | Decreased binge drinking and number of drinks consumed |

| Thompson et al., 2018 [29] | Canada | To evaluate the impact of the e-CHECKUP TO GO (e-CHUG) on drinking outcomes and perceived norms in first year university resident students | n = 245 first year college students in residence who engaged in alcohol consumption | Questions on alcohol use, alcohol-related harm, and social norm misperceptions; and AUDIT | Web-based BMI with PNF | Decreased norm misperceptions; reduced norm misperceptions associated with reduced drinking outcomes |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wolfson, L.; Stinson, J.; Poole, N. Gender Informed or Gender Ignored? Opportunities for Gender Transformative Approaches in Brief Alcohol Interventions on College Campuses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020396

Wolfson L, Stinson J, Poole N. Gender Informed or Gender Ignored? Opportunities for Gender Transformative Approaches in Brief Alcohol Interventions on College Campuses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(2):396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020396

Chicago/Turabian StyleWolfson, Lindsay, Julie Stinson, and Nancy Poole. 2020. "Gender Informed or Gender Ignored? Opportunities for Gender Transformative Approaches in Brief Alcohol Interventions on College Campuses" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 2: 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020396

APA StyleWolfson, L., Stinson, J., & Poole, N. (2020). Gender Informed or Gender Ignored? Opportunities for Gender Transformative Approaches in Brief Alcohol Interventions on College Campuses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020396