State of the Art of Family Quality of Life in Early Care and Disability: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What has been the conceptualization of the quality of life of families with a child who has a disability or developmental concerns between 0 and 6 years?

- (2)

- What instruments of FQoL directed to population with disability and that have adequate psychometric properties exist for the child stage (0–6 years)?

- (3)

- What are the main findings of the existing studies on FQoL in the 0–6 years stage?

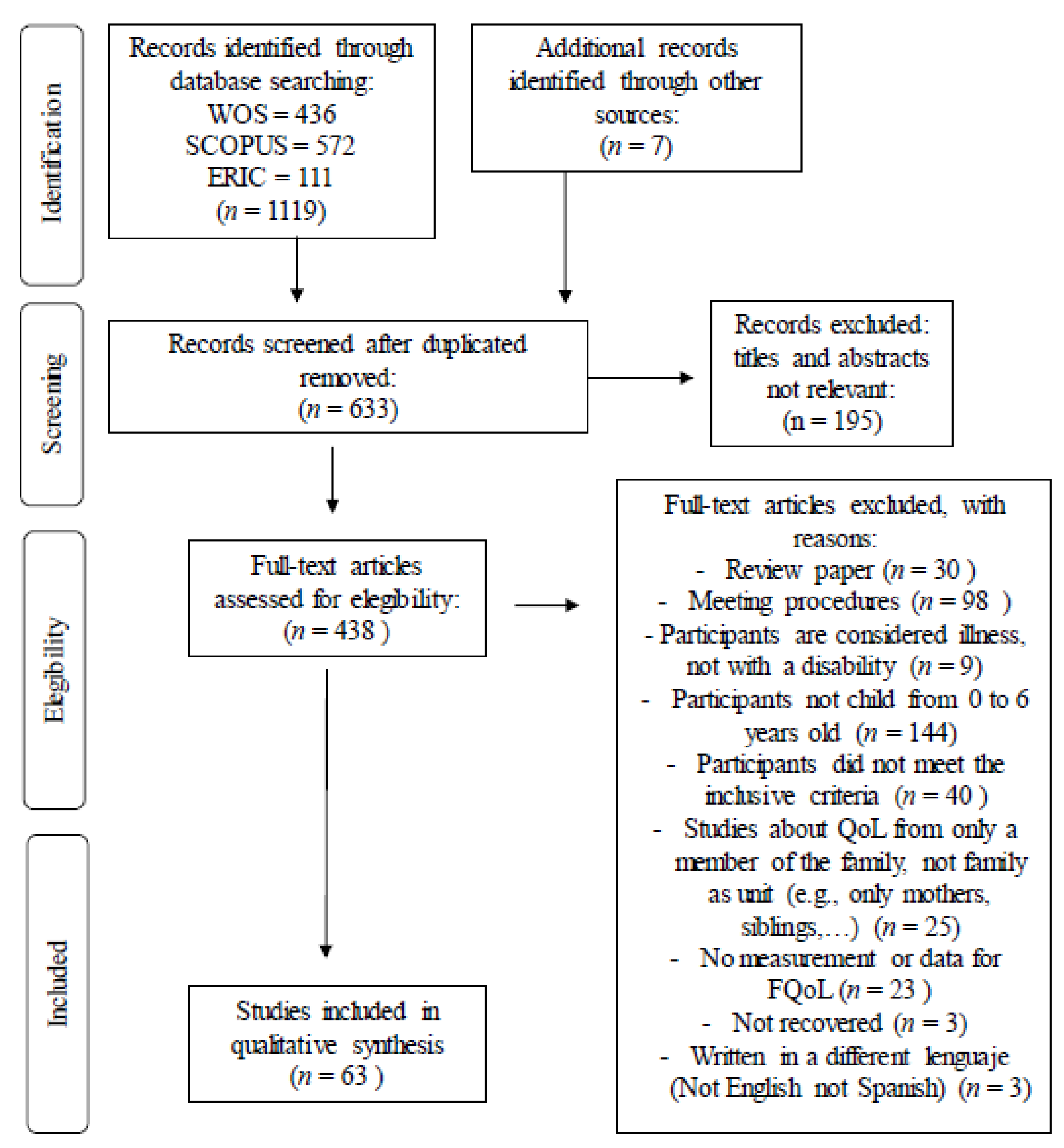

2. Method

- (a)

- the empirical studies were based on studies with samples that included families of children with disabilities and/or developmental issues within the 0 to 6 years stage;

- (b)

- the studies had been published after 1999, which is the year when the publications on FQL as a social construct and extension of the QoL of individuals with IDD started;

- (c)

- the studies were written in English or Spanish, as these are the languages used in most of the publications on this topic and the languages mastered by the authors of this article;

- (d)

- the studies were published in peer-review journals or as book chapters.

- (a)

- disability was considered a disease, since that would have entailed to discard the systematic approach in favor of the rehabilitative medical model;

- (b)

- FQoL was studied from an individual-based perspective (instead of the holistic model mentioned above which includes all the family members);

- (c)

- FQoL was conceptualized from a rehabilitative medical perspective, since we are interested in disability from a psychosocial approach.

3. Results

3.1. The Conceptualization of FQoL in the 0 to 6 Year Stage

3.1.1. Theoretical Conceptualization

3.1.2. Functional Conceptualization

3.2. Instruments that Measure the FQoL in the 0 to 6 Years Stage

3.3. Main Results on FQoL in the 0- to 6-Year Stage

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- Six articles relate the FQoL to a specific type of disability. Brown et al. [66], for instance, compared the QoL of three types of families: families with a child with Down syndrome, families with a child with autism spectrum disorders, and families with none of their members having a disability. The other five articles focus on specific disabilities, namely deafness [48], intellectual disability [32,67], autism [37] and rare metabolic diseases [68].

- (d)

- (e)

- Two articles relate the FQoL to perspectives of some of the family members. Moyson and Roeyers [72] investigated the FQoL from the perspective of the siblings of the person with disabilities. Wang et al., determined “whether mothers and fathers similarly view the conceptual model of FQoL embodied in one measure” [71] (pp. 977). This study shows that there are no significant differences between the perceptions of fathers and mothers.

- (f)

| Concepts of FQoL Theory (Zuna et al. [8]) | Authors (Year) (Chronological Order) | |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic concepts | Systems | No records have been identified |

| Policies | No records have been identified | |

| Programs | Hielkema et al., 2019, [74] | |

| Performance concepts | Services | Balcells-Balcells et al., 2019 [77]; Epley et al., 2011 [50]; Eskow et al., 2011 [43]; Kyzar et al., 2016 [46]; Samuel et al., 2012 [75]; Summers et al., 2007 [76]; Taub and Werner 2016 [49]; |

| Supports | Boehm et al., 2019 [84]; Cohen et al., 2014 [41]; Davis and Gavidia Payne, 2009 [79]; Hsiao et al., 2017 [78]; Kyzar et al., 2016 [46]; Kyzar et al., 2018 [85]; Meral et al., 2013 [80]; Samuel et al., 2011 [36]; Svavarsdottir and Tryggvadottir, 2019 [81]; Taub and Werner, 2016 [49] | |

| Practices | Davis and Gavidia Payne, 2009 [79] | |

| Individual-member concepts | Individual characteristics | Boehm et al., 2019 [84]; Davis and Gavidia Payne, 2009, [79]; Hsiao et al., 2017 [78]; Hsiao 2018, [82]; Levinger et al., 2018, [86]; Meral et al., 2013 [80]; Vanderkerken et al., 2018 [33]; Wang et al., 2004 [83]; |

| Demographic aspects | Meral et al., 2013 [80]; Cohen et al., 2014 [41]; Hsiao 2018 [82]; Kyzar et al., 2018 [85]; Levinger et al., 2018 [86]; Vanderkerken et al., 2018 [33]; Boehm et al., 2019 [84] | |

| Beliefs | Svavarsdottir and Tryggvadottir, 2019 [81] | |

| Family-unit concepts | Characteristics of the family | Boehm et al., 2019 [84]; Cohen et al., 2014 [41]; Davis and Gavidia Payne, 2009 [79]; Hsiao 2018 [82]; Hielkema et al., 2019 [74]; Kyzar et al., 2018; Schlebusch et al., 2016 [87]; Taub and Werner 2016 [49]; [85]; Wang et al., 2004 [83] |

| Family dynamics | Schlebusch et al., 2016 [87]; Levinger et al., 2018; [86]; Vanderkerken et al., 2018 [33]. |

4. Discussion

5. Implications

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Escorcia, C.T.; García-Sánchez, F.; Sánchez-López, M.C.; Hernández-Pérez, E. Cuestionario de estilos de interacción entre padres y profesionales en atención temprana: Validez de contenido. An. Psicol. 2016, 32, 148–157. [Google Scholar]

- Federación Estatal de Asociaciones de Profesionales de Atención Temprana (GAT). La Atención Temprana. La Visión de Los Profesionales. Available online: http://www.avap-cv.com/images/Documentos%20basicos/GAT-LA-VISI%C3%93N-DE-LOS-PROFESIONALES.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Bronfrenbrenner, U. La Ecología del Desarrollo Humano; Espasa: Barcelona, Spain, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J.S. La Educación, Puerta de la Cultura; Visor: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Guralnick, M.J. Why early intervention works. Infants Young Child. 2011, 24, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mas, J.M.; Baques, N.; Balcells-Balcells, A.; Dalmau, M.; Gine, C.; Gracia, M.; Vilaseca, R. Family Quality of Life for families in early intervention in Spain. J. Early Interv. 2016, 38, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillotta, F.; Kirby, N.; Shearer, J.A. Comparison of two ‘family quality of life’ measures: An australian study. In Enhancing the Quality of Life of People with Intellectual Disabilities: From Theory to Practice; Kober, R., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 305–348. [Google Scholar]

- Zuna, N.I.; Turnbull, A.; Summers, J.A. Family Quality of Life: Moving from measurement to application. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2009, 6, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadders-Algra, M.M.; Hielkema, A.G.B.; Hamer, E.G. Effect of early intervention in infants at very high risk of cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2017, 59, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.; Kyzar, K.; Zuna, N.; Turnbull, A.; Summers, J.A.; Aya Gómez, V. Family Quality of Life, Trends in family research related to family quality of life. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology and Disability; Wehmeyer, M.W., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 365–392. [Google Scholar]

- Dunst, C.J.; Bruder, M.B. Valued outcomes of service coordination, early intervention, and natural environments. Except. Child. 2002, 68, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhopti, A.; Brown, T.; Lentin, P. Family Quality of Life: A Key Outcome in Early Childhood Intervention Services A Scoping Review. J. Early Interv. 2016, 38, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, L.A.; Baird, S.M. Effects of service coordinator variables on individualized family service plans. J. Early Interv. 2003, 25, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, G.; Perales, F. El papel de los padres de niños con síndrome de Down y otras discapacidades en la atención temprana. Rev. Sínd. Down 2012, 29, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, P.S.; Pociask, F.D.; Dizazzo-Miller, R.; Carrellas, A.; LeRoy, B.W. Concurrent validity of the International Family Quality of Life Survey. Occup. Ther. Health Care 2016, 30, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuna, N.; Summers, J.A.; Turnbull, A.P.; Hu, X.; Xu, S. Theorizing about family quality of life. In Enhancing the Quality of Life of People with Intellectual Disabilities: From Theory to Practice; Kober, R., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 41, pp. 241–278. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.I.; Kyrkou, M.R.; Samuel, P.S. Family quality of life. In Health Care for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities across the Lifespan; Rubin, I.L., Merrick, J., Greydanus, D.E., Patel, D.R., Eds.; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 2065–2082. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, L.; Marquis, J.; Poston, D.; Summers, J.A.; Turnbull, A. Assessing Family Outcomes: Psychometric Evaluation of the Beach Center Family Quality of Life Scale. J. Marriage Fam. 2006, 68, 1069–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giné, C.; Vilaseca, R.; Gràcia, M.; Mora, J.; Orcasitas, J.R.; Simón, C.; Torrecillas, A.M.; Beltran, F.S.; Dalmau, M.; Pro, M.T.; et al. Spanish Family Quality of Life Scales: Under and over 18 Years Old. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 38, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, I.; Brown, R.I. Concepts for Beginning Study in Family Quality of Life. In Families and People with Mental Retardation and Quality of Life: International Perspectives; American Association on Mental Retardation: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.I.; Brown, I. Family Quality of Life. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, A.P.; Turnbull, H.R.; Poston, D.; Beegle, G.; BlueBanning, M.; Diehl, K.; Frankland, C.; Lord, L.; Marquis, J.; Park, J.; et al. Enhancing Quality of Life of Families of Children and Youth with Disabilities in the United States. A Paper Presented at Family Quality of Life Symposium; Seattle, W.A., Ed.; Beach Center on Families and Disability: Lawrence, KS, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, I.; Brown, R.I.; Baum, N.T.; Isaacs, N.J.; Myerscough, T.; Neikrug, S.; Wang, M. Family Quality Life Survey: Main Caregivers of People with Intellectual or Development Disabilities; Surrey Place Centre: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- García-Grau, P.; McWilliam, R.A.; Martínez-Rico, G.; Morales-Murillo, C. Rasch analysis of the families in early intervention quality of life (FEIQoL) Scale. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escorcia-Mora, C.T.; García-Sánchez, F.A.; Sánchez-López, M.C.; Orcajada, N.; Hernández-Pérez, E. Prácticas de intervención en la primera infancia en el sureste de España: Perspectiva de profesionales y familias. An. Psicol. 2018, 34, 500–509. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, E.; Liberati, A. Revisiones Sistemáticas y Metaanálisis: La responsabilidad de Los Autores, Revisores, Editores y Patrocinadores. Med. Clin. 2010, 135, 505–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Summers, J.A.; Turnbull, A.; Zuna, N. The quantitative measurement of family quality of life: A review of available instruments. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 1098–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Hoffman, L.; Marquis, J.; Turnbull, A.P.; Poston, D.; Mannan, H.; Wang, M.; Nelson, L.L. Toward assessing family outcomes of service delivery: Validation of a Family Quality of Life Survey. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2003, 47, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leadbiter, K.; Aldred, C.; McConachie, H.; Le Couteur, A.; Kapadia, D.; Charman, T.; Mcdonald, W.; Salomone, E.; Emsley, R.; Green, J. The Autism Family Experience Questionnaire (AFEQ): An ecologically- valid, parent-nominated measure of family experience, quality of life and prioritised outcomes for early intervention. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 1042–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, D.; Woloski, M.; Feeny, D.; McCusker, P.; Wu, J.; David, M.; Bussel, J.; Lusher, J.; Wakefield, C.; Henriques, S.; et al. Development of disease-specific health-related quality-of-life instruments for children with immune thrombocytopenic purpura and their parents. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2003, 25, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candel, D.; Dubois, D. Vers une définition de la « qualité de vie »? Rev. Francoph. Psycho. Oncologie 2005, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schertz, M.; Karni-Visel, Y.; Tamir, A.; Genizi, J.; Roth, D. Family Quality of Life among families with a child who has a severe neurodevelopmental disability: Impact of family and child socio-demographic factors. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 53–54, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderkerken, L.; Heyvaert, M.; Onghena, P.; Maes, B. Quality of Life in flemish families with a child with an intellectual disability: A multilevel study on opinions of family members and the impact of family member and family characteristics. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2018, 13, 779–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Quiroga, D.; Ariza-Araújo, Y.; Pachajoa, H. Family Quality of Life in Patients with Morquio Type IV-A Syndrome: The perspective of the colombian social context (South America). Rehabilitación 2018, 52, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillotta, F.; Kirby, N.; Shearer, J.; Nettelbeck, T. Family Quality of Life of Australian Families with a Member with an Intellectual/Developmental Disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, P.S.; Hobden, K.L.; LeRoy, B.W. Families of children with autism and developmental disabilities: A description of their community interaction. Res. Soc. Science and Disabil. 2011, 6, 49–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlebusch, L.; Dada, S.; Samuels, A.E. Family Quality of Life of south african families raising children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 1966–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Grau, P.; McWilliam, R.A.; Martínez-Rico, G.; Grau-Sevilla, M.D. Factor structure and internal consistency of a spanish version of the family quality of life (FaQoL). Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2017, 13, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcells-Balcells, A.; Giné, C.; Guàrdia-Olmos, J.; Summers, J.A. Family Quality of Life: Adaptation to spanish population of several family support questionnaires. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.Y.; Seo, H.; Turnbull, A.P.; Summers, J.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of a family quality of life scale for taiwanese families of children with intellectual disability/developmental delay. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 55, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.R.; Holloway, S.D.; Domínguez-Pareto, I.; Kuppermann, M. Receiving or believing in family Support? Contributors to the life quality of latino and non-latino families of children with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2014, 58, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demchick, B.B.; Ehler, J.; Marramar, S.; Mills, A.; Nuneviller, A. Family quality of life when raising a child with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS). J. Occup. Ther. Sch. Early Interv. 2019, 12, 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskow, K.; Pineles, L.; Summers, J.A. Exploring the effect of autism waiver services on family outcomes. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2011, 8, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Grau, P.; McWilliam, R.A.; Martinez-Rico, G.; Morales-Murillo, C.P. Child, Family, and early intervention characteristics related to family quality of life in Spain. J. Early Interv. 2018, 41, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, M.; Fei, X. Family quality of life of chinese families of children with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyzar, K.B.; Brady, S.E.; Summers, J.A.; Haines, S.J.; Turnbull, A.P. Services and supports, partnership, and Family Quality of Life: Focus on deaf-blindness. Except. Child. 2016, 83, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parpa, E.; Katsantonis, N.; Tsilika, E.; Galanos, A.; Sassari, M.; Mystakidou, K. Psychometric properties of the family quality of life scale in greek families with intellectual disabilities. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2016, 28, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.W.; Wegner, J.R.; Turnbull, A.P. Family Quality of Life following early identification of deafness. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2010, 41, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taub, T.; Werner, S. What support resources contribute to family quality of life among religious and secular jewish families of children with developmental disability? J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 41, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, P.H.; Summers, J.A.; Turnbull, A.P. Family Outcomes of early intervention: Families’ perceptions of need, services, and outcomes. J. Early Interv. 2011, 33, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, R.A.; Casey, A.M. Factor analysis of family quality of life (FaQoL). 2013; Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Verdugo, M.A.; Cordoba, L.; Gomez, J. Spanish Adaptation and Validation of the Family Quality of Life Survey. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2005, 49, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.-J.; Chen, P.-T.; Chou, Y.-T.; Chien, L.-Y. The mandarin chinese version of the Beach Centre Family Quality of Life Scale: Development and psychometric properties in taiwanese families of children with developmental delay. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2017, 61, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waschl, N.; Xie, H.; Chen, M.; Poon, K.K. Construct, Convergent, and Discriminant Validity of the Beach Center Family Quality of Life Scale for Singapore. Infants Young Child. 2019, 32, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Escamilla, N.; Rivadeneira, J.; Concha-Toro, M.; Soto-Caro, A.; Diaz-Martinez, X. Family Quality of Life Scale (FQLS): Validation and analysis in a chilean population. Univ. Psychol. 2017, 16, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivard, M.; Mercier, C.; Mestari, Z.; Terroux, A.; Mello, C.; Begin, J. Psychometric Properties of the Beach Center Family Quality of Life in french-speaking amilies with a preschool-aged child diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 122, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, A.; Isaacs, B. Validity of the Family Quality of Life Survey-2006. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2015, 28, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, P.S.; Tarraf, W.; Marsack, C. Family Quality of Life Survey (FQOLS-2006): Evaluation of internal consistency, construct, and criterion validity for socioeconomically disadvantaged families. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2018, 38, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba-Andrade, L.; Gómez-Benito, J.; Verdugo-Alonso, M.A. Family Quality of Life of people with disability: A comparative analyses. Univ. Psychol. 2008, 7, 369–383. [Google Scholar]

- Neikrug, S.; Roth, D.; Judes, J. Lives of Quality in the face of challenge in Israel. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.; Brown, R.; Karrapaya, R. An Initial look at the quality of life of malaysian families that include children with disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giné, C.; Gràcia, M.; Vilaseca, R.; Salvador Beltran, F.; Balcells-Balcells, A.; Dalmau Montalà, M.; Adam-Alcocer, A.L.; Teresa Pro, M.; Simó-Pinatella, D.; Mas Mestre, J.M. Family Quality of Life for people with intellectual disabilities in Catalonia. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2015, 12, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.A.; Fontanella, B.J.B.; de Avó, L.R.S.; Germano, C.M.R.; Melo, D.G. A Qualitative study about quality of life in brazilian families with children who have severe or profound intellectual disability. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2019, 32, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McStay, R.L.; Trembath, D.; Dissanayake, C. Stress and Family Quality of Life in Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Parent Gender and the Double ABCX Model. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 3101–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McStay, R.L.; Trembath, D.; Dissanayake, C. Maternal stress and Family Quality of Life in response to raising a child with autism: From preschool to adolescence. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35, 3119–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.I.; MacAdam-Crisp, J.; Wang, M.; Iaroci, G. Family Quality of Life when there is a child with a developmental disability. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2006, 3, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, K.; Fung, F.; Hu, A.; Sweller, N.; Wang, W. Understanding Hong Kong chinese families’ experiences of an autism/ASD diagnosis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 1164–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada-Ortigosa, E.M.; Flores-Rojas, K.; Moreno-Quintana, L.; Muñoz-Villanueva, M.C.; Pérez-Navero, J.L.; Gil-Campos, M. Health and socio-educational needs of the families and children with rare metabolic diseases: Qualitative study in a tertiary hospital. An. Pediatr. 2019, 90, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, S.D.; Dominguez-Pareto, I.; Cohen, S.R.; Kuppermann, M. Whose job is it? Everyday routines and quality of life in latino and non-latino families of children with intellectual disabilities. J. Ment. Health Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2014, 7, 104–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algood, C.; Davis, A.M. Inequities in family quality of life for african-american families raising children with disabilities. Soc. Work Public Health 2019, 34, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Summers, J.A.; Little, T.; Turnbull, A.; Poston, D.; Mannan, H. Perspectives of fathers and mothers of children in early intervention programmes in assessing Family Quality of Life. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2006, 50, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyson, T.; Roeyers, H. The overall quality of my life as a sibling is all right, but of course, it could always be better’. Quality of Life of siblings of children with intellectual disability: The siblings’ perspectives. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, R.; Poppe, L.; Vandevelde, S.; Van Hove, G.; Claes, C. Family Quality of Life in 25 belgian families: Quantitative and qualitative exploration of social and professional support domains. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 1123–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hielkema, T.; Boxum, A.G.; Hamer, E.G.; La Bastide-Van Gemert, S.; Dirks, T.; Reinders-Messelink, H.A.; Maathuis, C.G.B.; Verheijden, J.; Geertzen, J.H.B.; Hadders-Algra, M. LEARN2MOVE 0–2 years, a randomized early intervention trial for infants at very high risk of cerebral palsy: Family outcome and infant’s functional outcome. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, P.S.; Hobden, K.L.; Leroy, B.W.; Lacey, K.K. Analysing family service needs of typically underserved families in the USA. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, J.A.; Marquis, J.; Mannan, H.; Turnbull, A.P.; Fleming, K.; Poston, D.J.; Wang, M.; Kupzyk, K. Relationship of perceived adequacy of services, family-professional partnerships, and Family Quality of Life in early childhood service programmes. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2007, 54, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcells-Balcells, A.; Gine, C.; Guardia-Olmos, J.; Summers, J.A.; Mas, J.M. Impact of supports and partnership on Family Quality of Life. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 85, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.-J.; Higgins, K.; Pierce, T.; Whitby, P.J.S.; Tandy, R.D. Parental stress, family quality of life, and family-teacher partnerships: Families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 70, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, K.; Gavidia-Payne, S. The impact of child, family, and professional support characteristics on the Quality of Life in families of young children with disabilities. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 34, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meral, B.F.; Cavkaytar, A.; Turnbull, A.P.; Wang, M. Family Quality of Life of turkish families who have children with intellectual disabilities and autism. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2013, 38, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svavarsdottir, E.K.; Tryggvadottir, G.B. Predictors of Quality of Life for families of children and adolescents with severe physical illnesses who are receiving hospital-based care. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2019, 33, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.-J. Autism Spectrum Disorders: Family demographics, parental stress, and Family Quality of Life. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 15, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Turnbull, A.P.; Summers, J.A.; Little, T.D.; Poston, D.J.; Marman, H.; Turnbull, R. Severity of disability and income as predictors of parents’ satisfaction with their family quality of life during early childhood years. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2004, 29, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, T.L.; Carter, E.W. Family Quality of Life and its correlates among parents of children and adults with intellectual disability. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 124, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyzar, K.; Brady, S.; Summers, J.A.; Turnbull, A. Family Quality of Life and partnership for families of students with deaf-blindness. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2018, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinger, M.; Alhuzail, N.A. Bedouin hearing parents of children with hearing loss: Stress, coping, and Quality of Life. Am. Ann. Deaf 2018, 163, 328–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlebusch, L.; Samuels, A.E.; Dada, S. South african families raising children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Relationship between family routines, cognitive appraisal and Family Quality of Life. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2016, 60, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbull, A.P.; Summers, J.A.; Lee, S.-H.; Kyzar, K. Conceptualization and measurement of family outcomes associated with families of individuals with intellectual disabilities. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2007, 13, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schippers, A.; Zuna, N.; Brown, I. A Proposed framework for an integrated process of improving quality of life. J. Policy. Pract. Intellect Dis. 2015, 12, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelsma, F.; Caubo-Damen, I.; Schippers, A.; Dane, M.; Abma, T.A. Rethinking FQoL: The dynamic interplay between individual and Family Quality of Life. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2017, 14, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, E.; Iarocci, G. Family Quality of Life and ASD: The role of child adaptive functioning and behavior problems. Autism Res. 2015, 8, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heumen, L.; Schippers, A. Quality of Life for young adults with intellectual disability following individualised support: Individual and family responses. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 41, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, D.; Brown, I. Social and Cultural Considerations in Family Quality of Life: Jewish and Arab Israeli Families’ Child-Raising Experiences. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2017, 14, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijkx, J.; van der Putten, A.A.J.; Vlaskamp, C. “I love my sister, but sometimes I don’t”: A qualitative study into the experiences of siblings of a child with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 41, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, R.; Barnetz, Z.; Davidson-Arad, B. Quality of Life in family members coping with chronic illness in a relative: An exploratory study. Fam. Syst. Health 2008, 25, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Mannan, H.; Poston, D.; Turnbull, A.P.; Summers, J.A. Parents’ Perceptions of advocacy activities and their impact on Family Quality of Life. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2004, 29, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z. The Quality of Family Life and lifestyle. In The Chinese Family Today; Xu, A., Defrain, J., Liu, W., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016; Volume 7, pp. 248–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderkerken, L.; Heyvaert, M.; Onghena, P.; Maes, B. Mother Quality of Life or Family Quality of Life? A survey on the Quality of Life in families with children with intellectual disabilities using home-based support in Flanders. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2016, 60, 756. [Google Scholar]

| Plataform | Results | Search | Languages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | 563 | “Family Quality of Life” OR “Quality of Family Life” | English |

| 9 | “Calidad de Vida Familiar” | Spanish | |

| WOS | 416 | “Family Quality of Life” OR “Quality of Family Life” | English |

| 20 | “Calidad de Vida Familiar” | Spanish | |

| Eric | 107 | “Family Quality of Life” OR “Quality of Family Life” | English |

| 4 | “Calidad de Vida Familiar” | Spanish | |

| Total | 1119 |

| Definitions of Family Quality of Life | Articles |

|---|---|

| Conditions where the family’s needs are met, and family members enjoy their life together as a family and have the chance to do things which are important to them. | Turnbull et al. [22] Cited by Park et al. [28] (pp. 368) |

| It can be said that families experience a satisfactory quality of family life when: (a) they achieve what families around the world, and they in particular, strive to achieve; (b) they are satisfied with what families around the world, and they in particular, have achieved; (c) they feel empowered to live the lives they wish to live. | Brown and Brown [20] (pp. 32) |

| Family quality of life is a dynamic sense of well-being of the family, collectively and subjectively defined and informed by its members, in which individual and family-level needs interact. | Zuna et al. [16] (pp. 262) |

| Family quality of life is concerned with the degree to which individuals experience their own quality of life within the family context, as well as with how the family as a whole has opportunities to pursue its important possibilities and achieve its goals in the community and the society of which it is a part. | Brown and Brown [21] (pp. 2195) |

| Beach Center FQoL scale (Hoffman et al. [18]) 5 Domains | FQoLsurvey-2006 International Project (Brown et al. [17]) 9 Domains | FQoL-S (Giné et al. [19]) 7 Domains | The Autism Family Experience Questionnaire (AFEQ) (Leadbiter et al. [29]) 4 Domains | ITP-Child Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (Barnard et al. [30]) 5 Domains | Feiqol-Family Early Intervention Quality of Life (Garcia-Grau et al. [24]) 3 Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family Interaction 2. Parenting 3. Emotional Well-being 4. Physical-Well-being material 5. Disability Related Support | 1. Health 2. Finances 3. Family Relationships 4. Informal Support 5. Service Support 6. Influence of values 7. Career path 8. Leisure and free time 9. Community | 1. Emotional well-being 2. Family Interaction 3. Health 4. Final well-being 5. Organization and parenting skills 6. Accomodation of the family 7. Social Inclusion and Participation | 1. Parents 2. Family 3. Child development 4. Child symptoms | 1. Treatment side effect-related 2. Intervention related 3. Disease-related 4.Activity-related 5. Family-related | 1. Family Relationships 2. Access to Information and Services 3. Child Functioning |

| Instruments and Authors | Respond | Domains | Dimensions | Number of Items and Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Autism Family Experience Questionnaire (AFEQ) (Leadbiter et al. [29]) | Parents | 4 domains: (1) Parents; (2)Family; (3) Child development; (4) Child symptoms | Likert Scale of frequency 1 to 5 points (with “not applicable” option) | 56 items |

| ITP-Child Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (Barnard et al. [30]) | Parents | 5 domains: (1) treatment side effect-related; (2) intervention related; (3) disease-related; (4) activity-related; and (5) family-related | Likert scale of frequency and importance 1 to 5 points | 26 items |

| Family Early Intervention Quality of Life (FEIQoL) García Grau et al. [24] * | 3 Factors: (1) Family Relationships; (2) Access to Information and Services; (3) Child Functioning | Likert Scale 1 to 5 points of “poor” to “excellent” | 40 items |

| Scales | Development, Validation or Adaptation Studies | Country |

|---|---|---|

| Beach Center FQoL Scale (Hoffman et al., 2006) [18] | Balcells-Balcells et al., 2011 [39]; Verdugo et al., 2005 [52] | Spain |

| Chiu et al., 2017 [40]; Chiu et al., 2017 [53] | Hong Kong | |

| Waschl et al., 2019 [54] | Singapore | |

| Bello-Escamilla et al., 2017 [55]; | Chile | |

| Rivard et al., 2017 [56] | Canada | |

| FQOL Survey-2006 (Brown et al., 2006) [17] | Perry e Isaacs 2015 [57]; Samuel et al., 2016 [15]; Samuel et al., 2018 [58] | USA |

| Theme | Authors (Year) (Chronological Order) |

|---|---|

| Population | Córdoba et al., 2008 [59]; Neikrug et al., 2011 [60]; Clark et al., 2012 [61]; Rillotta et al., 2012 [35]; Giné et al., 2015 [62]; Mas et al., 2016 [6]; Schertz et al., 2016 [32]; García Grau et al., 2018 [44]; Rodrigues et al., 2018 [63]. |

| Maternal Outcomes | McStay et al., 2014 [64,65]. |

| Type of disability | Brown et al., 2006 [66]; Jackson et al., 2010 [48]; Schertz et al., 2016 [32]; Tait et al., 2016 [67]; Schlebusch et al., 2017 [37]; Tejada-Ortigosa et al., 2019 [68]. |

| Ethnic perspective | Holloway et al., 2014 [69]; Algood and Davis, 2019 [70]. |

| Attention to participants | Wang et al., 2006 [71]; Moyson and Roeyers, 2012 [72]. |

| Supports | Steel et al., 2011 [73]; Escorcia-Mora et al., 2018 [25]. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Francisco Mora, C.; Ibáñez, A.; Balcells-Balcells, A. State of the Art of Family Quality of Life in Early Care and Disability: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197220

Francisco Mora C, Ibáñez A, Balcells-Balcells A. State of the Art of Family Quality of Life in Early Care and Disability: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(19):7220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197220

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrancisco Mora, Carmen, Alba Ibáñez, and Anna Balcells-Balcells. 2020. "State of the Art of Family Quality of Life in Early Care and Disability: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 19: 7220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197220

APA StyleFrancisco Mora, C., Ibáñez, A., & Balcells-Balcells, A. (2020). State of the Art of Family Quality of Life in Early Care and Disability: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197220