“My Friends are at the Bottom of My Schedule”: A Qualitative Study on Social Health among Nursing Students during Clinical Placement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. QOL among Nursing Students and Nurses

2.2. Social Health Among Nursing Students and Nurses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Method and Participants

Participant Sample Characteristics

3.2. Ethical Considerations

3.3. Analysis

3.4. Trustworthiness

3.5. Cohesion between Interviews

4. Results

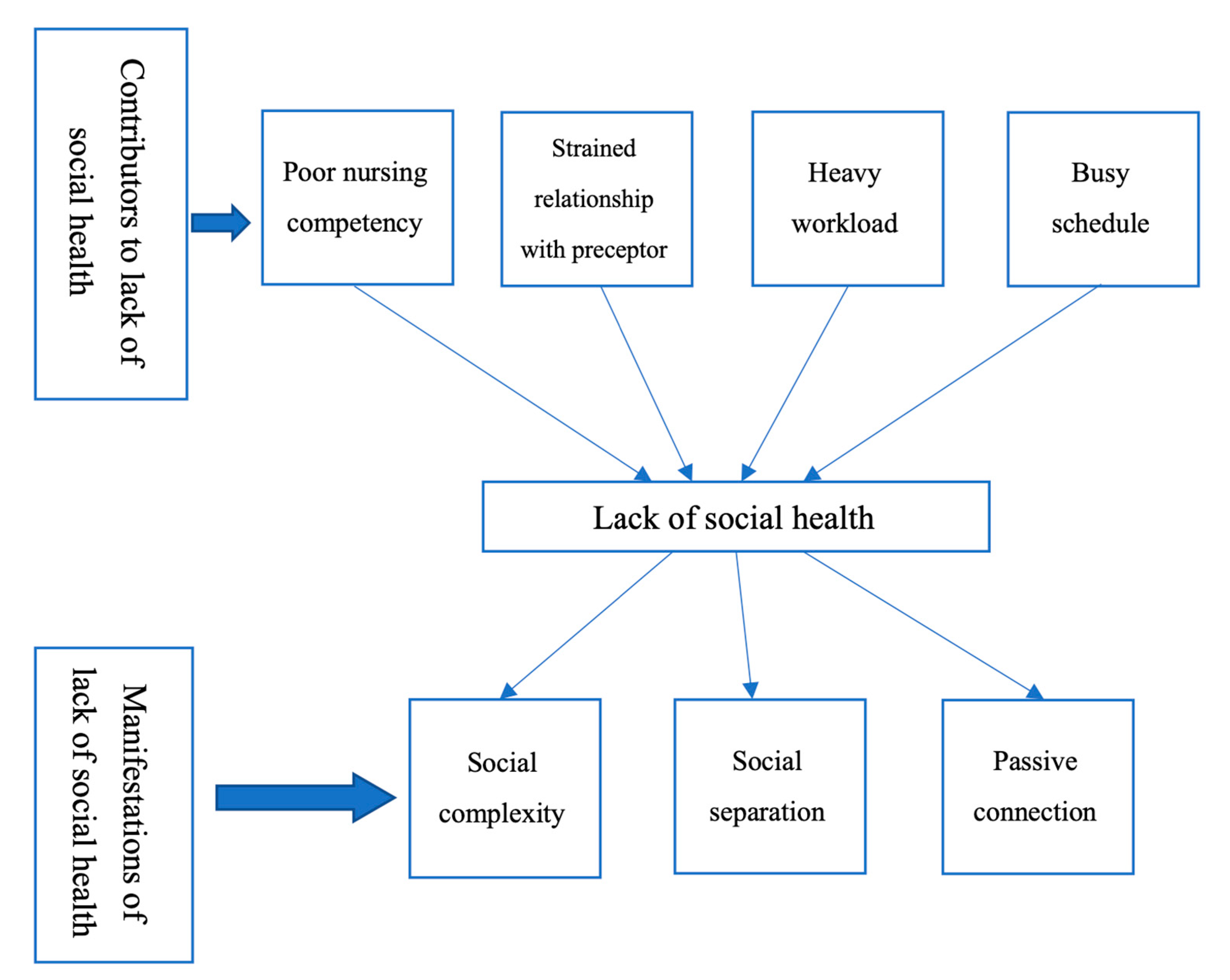

4.1. Contributors to Lack of Social Health

4.2. Manifestations of Lack of Social Health

4.2.1. Social Complexity

4.2.2. Social Separation

4.2.3. Passive Connection

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Implications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Birks, M.; Bagley, T.; Park, T.; Burkot, C.; Mills, J. The impact of clinical placement model on learning in nursing: A descriptive exploratory study. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 34, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, H.C.; Wang, H.H.; Weng, W.C. Nursing students’ perceptions toward the nursing profession from clinical practicum in a baccalaureate nursing program–A quality study. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2013, 29, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saifan, A.; AbuRuz, M.E.; Masa’deh, R. Theory practice gaps in nursing education: A qualitative perspective. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulman, C.; Schutz, S. Reflective Practice in Nursing, 5th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2013; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, K.; Fink, R.; Jaynes, C.; Campbell, L.; Cook, P.; Wilson, V. Readiness for practice: The senior practicum experience. J. Nurs. Educ. 2011, 50, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarshenas, L.; Sharif, F.; Molazem, Z.; Khayyer, M.; Zare, N.; Ebadi, A. Professional socialization in nursing: A qualitative content analysis. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2014, 19, 432–438. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, A.; Lu, S.; Lin, Y.; He, M. A scoping review on the influencing factors and development process of professional identity among nursing students and nurses. J. Prof. Nurs. (in press). [CrossRef]

- WHOQOL: Measuring Quality of Life. Available online: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whoqol-qualityoflife/en/ (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Cruz, J.P.; Felicilda-Reynaldo, R.F.D.; Lam, S.C.; Machuca Contreras, F.A.; John Cecily, H.S.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Fouly, H.A.; Kamau, S.M.; Valdez, G.F.D.; Adams, K.A.; et al. Quality of life of nursing students from nine countries: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 66, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, Í.J.S.; Pereira, R.; Freire, I.V.; de Oliveira, B.G.; Casotti, C.A.; Boery, E.N. Stress and quality of life among university students: A systematic literature review. Health Prof. Educ. 2018, 4, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzayyat, A.; Al-Gamal, E. A review of the literature regarding stress among nursing students during their clinical education. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2014, 61, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, J.; Weaver, S.; Bryan, V.; Lindo, J.L.M. Factors that influenced the clinical learning experience of nursing students at a Caribbean school of nursing. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2016, 6, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, B.; Trace, A.; O’Donovan, M.; Brady-Nevin, C.; Murphy, M.; O’Shea, M.; O’Regan, P. Nursing and midwifery students’ stress and coping during their undergraduate education programmes: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 61, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, I.M.D.M.; Paro, H.B.M.d.S.; Morales, R.R.; Pino, R.d.M.C.; Silva, C.H.M.d. Health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in undergraduate nursing students. Rev. Lat. -Am. Enferm. 2012, 20, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowrouzi, B.; Giddens, E.; Gohar, B.; Schoenenberger, S.; Bautista, M.C.; Casole, J. The quality of work life of registered nurses in Canada and the United Sates: A comprehensive literature review. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2016, 22, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Social well-being. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1988, 61, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, N.; Peyrovi, H.; Dehghan Nayeri, N.D. The social well-being of nurses shows a thirst for a holistic support: A qualitative study. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well Being 2015, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, G.C.S.; Paragas, E.D., Jr. Social determinants associated with the quality of life of baccalaureate nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Nurs. Forum 2019, 54, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What is the WHO Definition of Health? Available online: https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/frequently-asked-questions (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Gibbons, C. Stress, coping and burn-out in nursing students. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Lente, E.; Barry, M.M.; Molcho, M.; Morgan, K.; Watson, D.; Harrington, J.; McGee, H. Measuring population mental health and social well-being. Int. J. Public Health 2012, 57, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Population Density (People per sq. km of Land Area). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.POP.DNST?end=2019&most_recent_value_desc=true&start=1961&view=chart (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- GDP per Capita (Current US$). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?most_recent_value_desc=true (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Martos, M.; Augusto-Landa, J.M.; Lopez-Zafra, E. Sources of stress in nursing students: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2012, 59, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, P.; Kianipour, N.; Ziapour, A. A study of the status of students’ social health at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences and the role of demographic variables. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2018, 12, VC10-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, N.; Dadkhah, B.; Shamshiri, M.; Mohammadi, M.A.; Dehghan Nayeri, N.D. The status of social well-being in Iranian nurses: A cross-sectional study. J. Caring Sci. 2014, 3, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aronsson, G.; Theorell, T.; Grape, T.; Hammarström, A.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Träskman-Bendz, L.; Hall, C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout. Bmc Public Health 2017, 17, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pumpuang, W.; Seeherunwong, A.; Vongsirimas, N. Factors predicting intention among nursing students to seek professional psychological help. Pac. Rim Int. J. Nurs. Res. 2018, 22, 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, J.E.; Horwood, L.J.; Fergusson, D.M. Reasons why young adults do or do not seek help for alcohol problems. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2007, 41, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, B.R.C.; Pinto, I.C.J.F. Stress, burnout and coping in health professionals: A literature review. J. Psychol. Brian Stud. 2017, 1, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, M.J.; Schorling, J.B. A mindfulness course decreases burnout and improves well-being among healthcare providers. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2012, 43, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puolakanoho, A.; Tolvanen, A.; Kinnunen, S.M.; Lappalainen, R. A psychological flexibility-based intervention for Burnout: A randomized controlled trail. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 2020, 15, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlo, J.; Feeley, D. Why focusing on professional burnout is not enough. J. Healthc. Manag. 2018, 63, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyendo, T.O. Exploring the effect of sound and music on health in hospital settings: A narrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 63, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | N (%) or Range |

|---|---|

| Gender Female | 21 (100%) |

| Age Range | 22–25 |

| Race Chinese | 21 (100%) |

| Application to study nursing Self-apply Referred by secondary school | 17 (81%) 4 (19%) |

| Nursing as the first choice Yes No | 8 (38%) 13 (62%) |

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Exemplary Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Contributors to lack of social health | Poor nursing competency | …I am afraid of being questioned [about the knowledge] by my preceptor. (Participant 21) |

| …I was not used to work independently as I worked in group over the last three years. (Participant 02) | ||

| Strained relationship with preceptor | …If you had different viewpoints from your preceptor, conflict could arise. You needed to know how to communicate with your preceptor. (Participant 18) | |

| …The preceptor did not spend much time to know you. She followed what she was used to do in clinical environment. You needed to follow her steps. (Participant 05) | ||

| Heavy workload | …The stressors came from everywhere such as patient’s condition, workload in ward and projects from college. (Participant 06) | |

| Busy schedule | …I found I had less leisure time since I was not used to the arrangement of placement and life. (Participant 10) | |

| Manifestations of lack of social health | Social complexity | …At the beginning (of clinical placement), it was very stressful. I put most of my effort on studying, preparation for placement and sleep. I could not do other things. (Participant 07) …I needed to make preparation… Because of the roster, I did not have a day off for months. (Participant 03) |

| Social separation | …I told my friends not to find me in this year. I had clinical placements and work in shift…I would call you once I was free and they kept silent…My friends were at the bottom, while the (clinical placement related) workgroups were on the top of the list in the communication application. (Participant 14) …I joined a dancing group when I was in secondary school…I kept active in the group…I had thought of withdrawal because of the clinical placement in this year. (Participant 8) | |

| Passive connection | …Although they (family members) did not participate in my learning process, they would support me in another way. For instance, they made some delicious foods and created a silent environment. They used different strategies to facilitate my learning. (Participant 8) …My family celebrated with me, but I did not know it was the Easter day that day. (Participant 3) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tam, H.L.; Mao, A.; Cheong, P.L.; Van, I.K. “My Friends are at the Bottom of My Schedule”: A Qualitative Study on Social Health among Nursing Students during Clinical Placement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186921

Tam HL, Mao A, Cheong PL, Van IK. “My Friends are at the Bottom of My Schedule”: A Qualitative Study on Social Health among Nursing Students during Clinical Placement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(18):6921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186921

Chicago/Turabian StyleTam, Hon Lon, Aimei Mao, Pak Leng Cheong, and Iat Kio Van. 2020. "“My Friends are at the Bottom of My Schedule”: A Qualitative Study on Social Health among Nursing Students during Clinical Placement" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 18: 6921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186921

APA StyleTam, H. L., Mao, A., Cheong, P. L., & Van, I. K. (2020). “My Friends are at the Bottom of My Schedule”: A Qualitative Study on Social Health among Nursing Students during Clinical Placement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186921