Implementing Mental Health Promotion Initiatives—Process Evaluation of the ABCs of Mental Health in Denmark

Abstract

1. Background

1.1. The ABCs of Mental Health

1.1.1. Origin of the ABCs of Mental Health

“‘Act’ means that individuals should strive to keep themselves physically, socially and cognitively active. […]

‘Belong’ refers to being a member of a group or organisation (whether face-to-face or not), such that an individual’s connectedness with the community and sense of identity are strengthened. […]

‘Commit’ refers to the extent to which an individual becomes involved with (or commits to) some activity or organisation. Commitment provides a sense of purpose and meaning in people’s lives.”[10]

1.1.2. Organisation of the ABCs of Mental Health

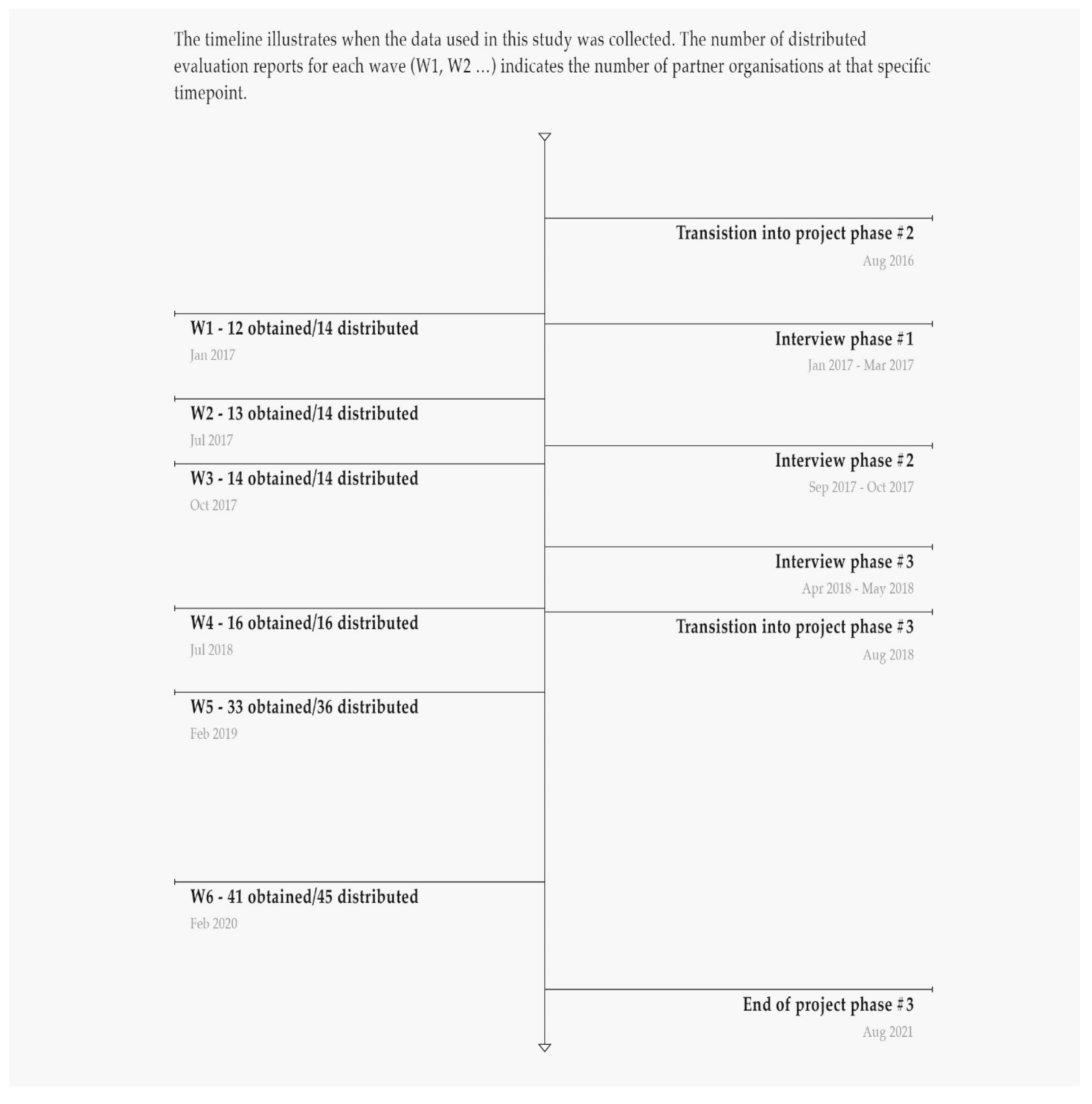

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Evaluation Questionnaires

2.4. Interviews

2.5. Analyses

3. Findings

3.1. Overall Characteristics of the MHP Initiatives—Three Strategies

- building capacity to work with MHP (e.g., by providing staff training and promoting intersectoral and interprofessional collaboration);

- campaign activities to promote mental health awareness and knowledge (e.g., online advertisements and campaign events); and

- establishing and promoting opportunities to engage in mentally healthy activities (e.g., volunteer led walking groups and community kitchens).

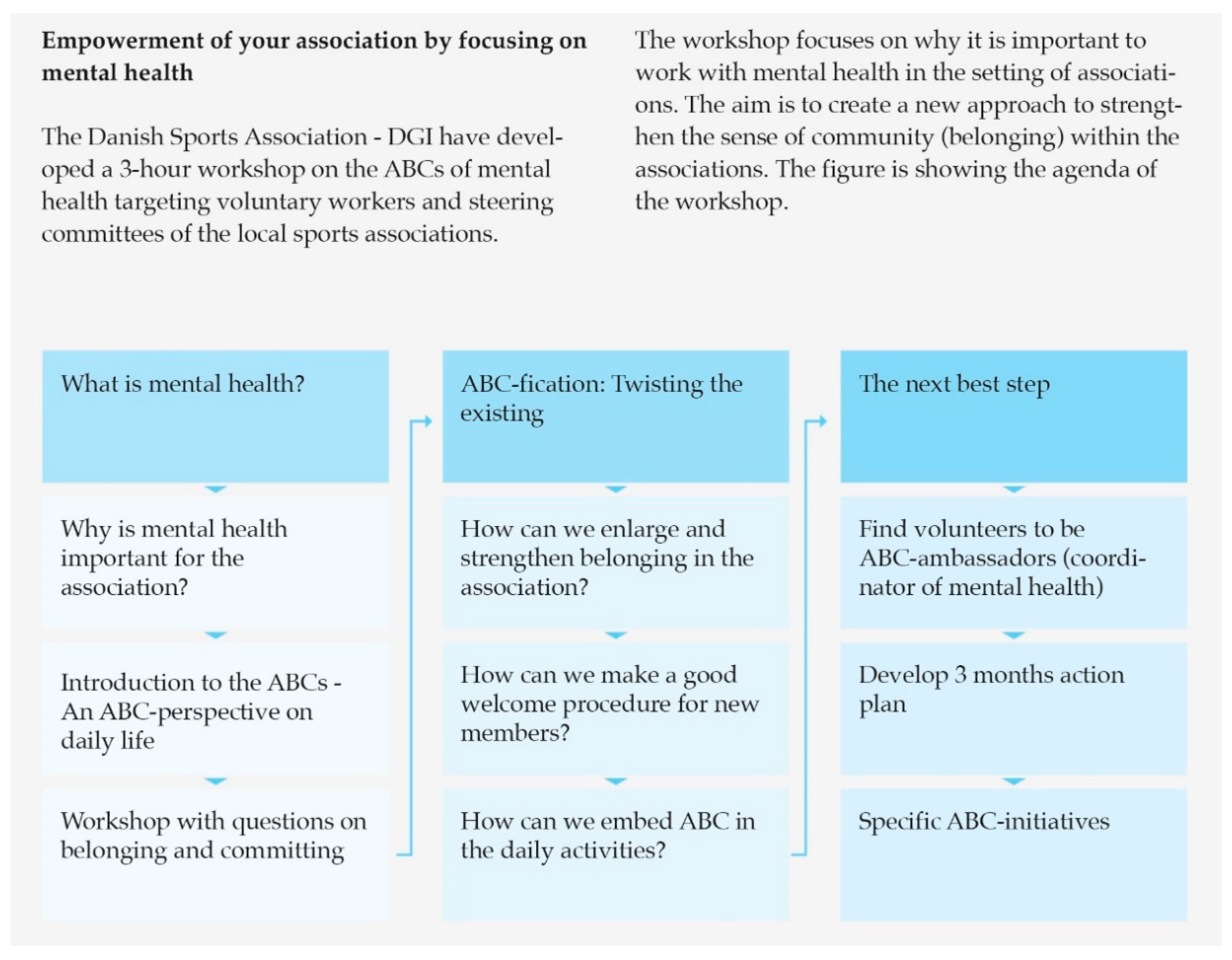

3.1.1. Building MHP Capacity

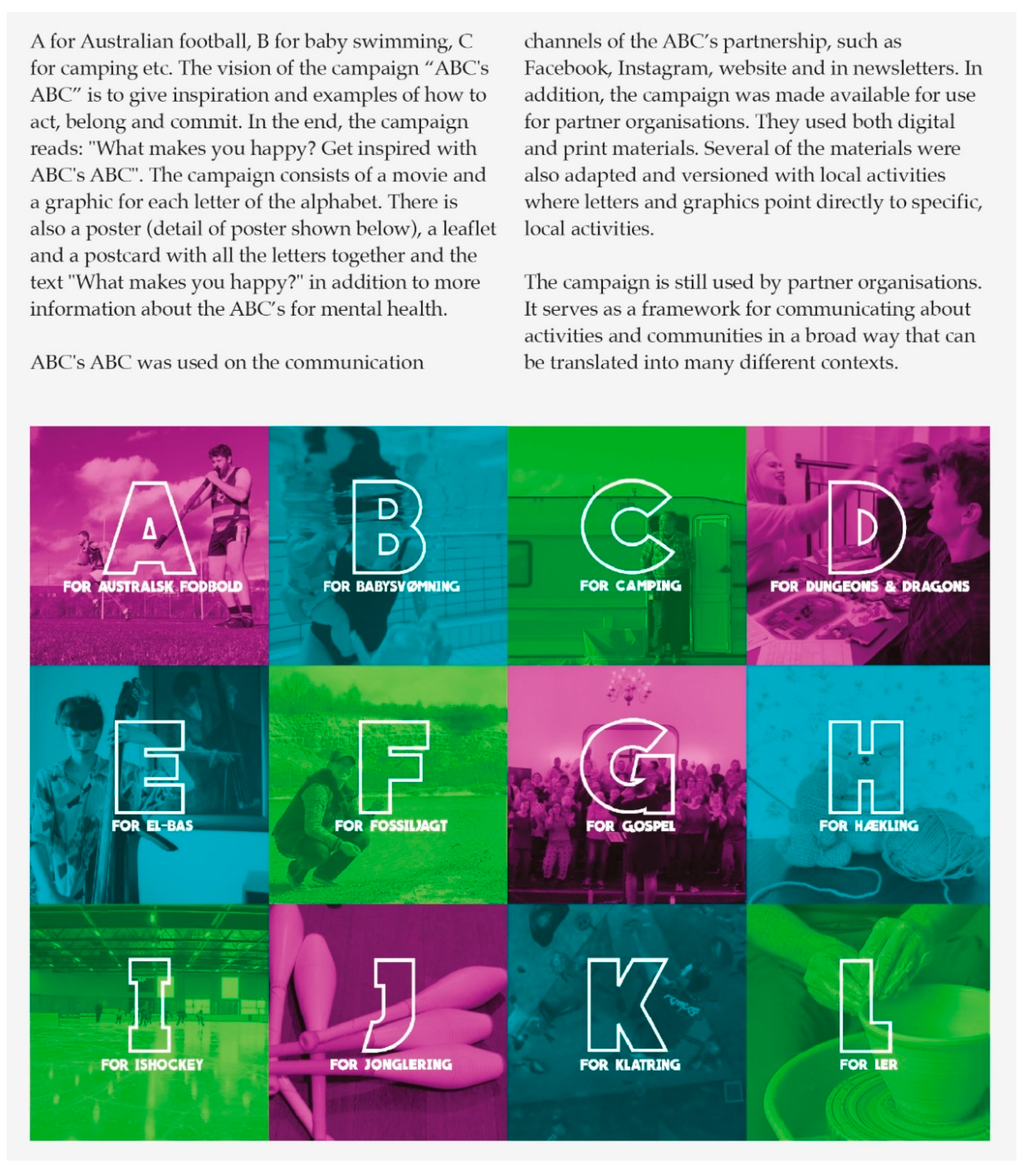

3.1.2. Campaign Activities

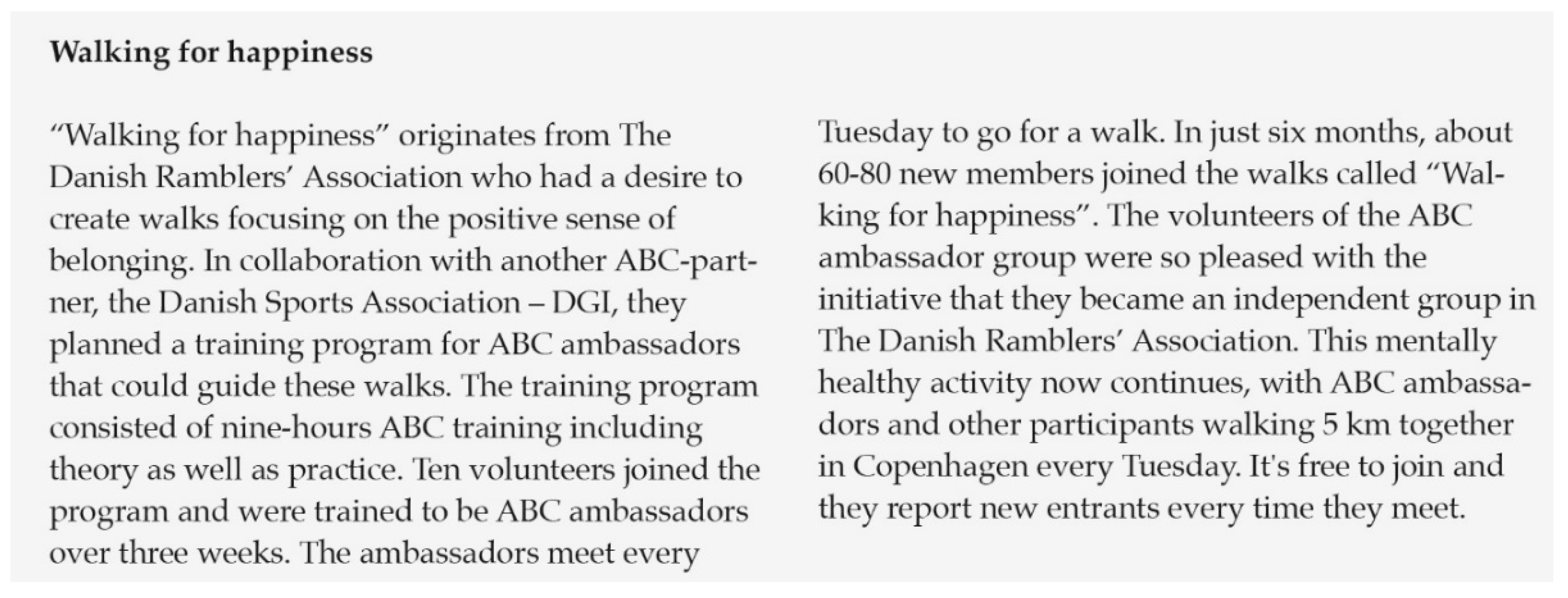

3.1.3. Mentally Healthy Activities

3.2. Qualitative Findings of the Perceptions of the Implementation Process and the Impact

3.2.1. Characteristics of Individuals

Attitudes toward the ABCs

“So thanks to your three messages [ABC-messages] one is actually enabled in working with the entire health promotion methodology. That is without having to complicate things or talk a lot about it.”(Interview, coordinator, municipality 1)

“The broad frame of understanding encompassed by the ABCs enables working with mental health at all levels; from political decision makers and cross disciplinary management areas down to the local citizen. Furthermore, we can see a great potential in translating the ABC-framework to locally based methods, initiatives and tools to support activities in promoting mental health.”(Questionnaire W2, municipality 3)

3.2.2. Characteristics of the Intervention

Credibility and Campaign Appeal Forms

“The fact that the ABCs of mental health is research-based has created credibility from the beginning—albeit that the three domains [act, belong and commit] are obvious for many, it is still meaningful for people to be confirmed that what they are doing is in the right direction.”(Questionnaire W4, NGO 1)

“Rather than being completely submerged in risk, treatment, shouldn’t and must, then try looking at the fact that there is something that may benefit you in other areas. To me that is exactly what the ABCs enables. As you say, patient associations entail a sort of community with mutual interests and so on, so to me it (the ABC’s) makes sense in several areas.”(Group interview, coordinator, municipality 2)

“But no one wants to join the scouts because they’re overweight. That’s also not why you take up football or something else. So this ‘hey, you need to find out what makes you happy’ and ‘what it is that gives you the energy to smile at the other cyclists’ and stuff like that, that is the focus that decides if you join the scouts …”(Interview, coordinator, NGO 2)

3.2.3. Process

Engaging Others as an Essential and Challenging Aspect of the Implementation Process

“Overall, the ABCs of mental health have contributed with a method to talk about mental health and wellbeing as well as incorporating mental health in the health promoting work, because all groups of employees understand the ABC messages because they are simple and relevant for most people.”(Questionnaire W4, municipality 1)

“There is a great interest in and accept of the ABC’s as a method. Most employees with contact to citizens think the ABC’s is meaningful as a framework to talk about being active and sense of community.”(Questionnaire W5, Municipality 4)

“We have been able to concretise and put some simple words on how we can help promote population mental health. Something we probably already did sporadically and in a more complicated manner but that we can now clearly formulate.”(Questionnaire W4, NGO3)

“That is the difficult aspect of this, trying to communicate it (the ABC-framework), concretize it, and make it manageable and actionable. That is those next steps.”(Interview, coordinator, NGO 3)

“… how can we as a municipality motivate and concretize “what’s in it for me” for the local collaborative partners?”.(Interview, coordinator, municipality 2)

“The ABCs is in many ways a simple tool, but nevertheless a tool that needs to be contextualized and adapted depending on the audience. Many local stakeholders, service providers, and municipal partners don’t consider themselves “mental health ambassadors” although they know that their activities promote wellbeing. Also, they don’t use the words “mental health” in their everyday activities. As an ABC-coordinator you therefore need to be able to relate to the context of various local stakeholders and use words that in their setting can be translated and equal mental health such as “feeling good” and “being happy”. Sometimes that means letting go of the words “mental health” and “the ABCs of mental health” because when it comes down to it, the local stakeholders decide for themselves how the ABCs are to be used and highlighted in their activities. That doesn’t mean that they don’t do ABC-activities—just that they have adapted the messages, so they work and live in their organisation.”(Questionnaire W4, municipality 3)

“It isn’t something extra (you need to do), it is just something that can help support you in reaching the goals you are meant to. That is what I find resonates with people. It isn’t rocket-science. It is a way of communicating so practitioners can see, that this is a method that can help them achieve their goals. … You find resources in working with health promotion that makes their job easier.”(Interview, coordinator, municipality 1)

“The ABC-framework has provided a clear message but has given loose boundaries in relation to developing and letting the ABCs take shape according to the context and resources. To some degree this has been liberating as it has provided the ABC-coordinator with the freedom to act on and to form the project locally. On the other hand, at times, as an ABC-coordinator, you needed an indicator that allowed you to set the standards for your work and guide you in terms of being on the right track.”(Questionnaire W4, municipality 3)

3.2.4. Inner Setting

Challenges Related to Producing an Economic Case for MHP Initiatives

“So it depends a lot on the economy of it all. And I also think that it is really really difficult to prove that we might save money. Because it is in the future. It is difficult to calculate how much money we might save, and this is always required, when we do these types of things. How much will we save in the future, because we are doing this now?”(Interview, stakeholder, municipality 2)

3.2.5. Outer Setting

Positive Feedback from End-Users on ABC-Initiatives and ABC-Messages

“I find it a challenge that it is called mental health. It creates a barrier in our world. If it was “happy” or “thriving”. I mean if you could find other words to describe it, because it becomes somewhat clinical. When I say something with mental health I hurry up and add ‘active’ or ‘belonging’.”(Interview, coordinator, NGO 2)

Promoting Interorganisational Collaborations through MHP

The Partnership as a Source of Resources

“At the same time, we can learn something from the other partners. That is the balance that makes a partnership interesting. That we can influence and contribute with something we are particularly good at. But it is also interesting that we can mirror ourselves in other organisations and the way they do things. Or learn something from how others receive this type of project and how they work with it. I find that is the balance that makes it rewarding.”(Interview, stakeholder, NGO 2)

“In the ABCs we inform people that even small adjustments and reprioritizing in your everyday life can help promote your mental health. However, not all citizens, organisations or workplaces have the creativity or energy to devise what these changes might be.”(Questionnaire W3, municipality 3)

3.3. Perceived Impact–Quantitatively Assessed

3.3.1. Characteristics of Respondents

3.3.2. Response Frequencies for Items on Perceived Impact

4. Discussion

4.1. A Novel Approach to MHP?

4.2. Balancing Adaptability and Guidance

4.3. Responsibility for Ensuring MHP Initiatives

4.4. Methodological Considerations

4.5. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campion, J.; Bhui, K.; Bhugra, D. European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on prevention of mental disorders. Eur. Psychiatry 2012, 27, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteford, H.A.; Ferrari, A.J.; Degenhardt, L.; Feigin, V.; Vos, T. The global burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders: An analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro, J.M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Bitter, I.; Demotes-Mainard, J.; Leboyer, M.; Lewis, S.W.; Linszen, D.; Maj, M.; McDaid, D.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; et al. ROAMER: Roadmap for mental health research in Europe. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 23 (Suppl. 1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Mental Health—Action Plan 2013–2020; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mathers, C.D.; Loncar, D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, e442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, G.; Christodoulou, G.; Jenkins, R.; Tsipas, V.; Christodoulou, N.; Lecic-Tosevski, D.; Mezzich, J.; Bhugra, D.; European Psychiatry, A. Mental health promotion: Guidance and strategies. Eur. Psychiatry 2012, 27, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar-McHenry, J.; Donovan, R.J. The development of the Perth Charter for the Promotion of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2013, 15, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsman, A.K.; Wahlbeck, K.; Aaro, L.E.; Alonso, J.; Barry, M.M.; Brunn, M.; Cardoso, G.; Cattan, M.; de Girolamo, G.; Eberhard-Gran, M.; et al. Research priorities for public mental health in Europe: Recommendations of the ROAMER project. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koushede, V.; Nielsen, L.; Meilstrup, C.; Donovan, R.J. From rhetoric to action: Adapting the Act-Belong-Commit Mental Health Promotion Programme to a Danish context. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2015, 17, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, R.J.; James, R.; Jalleh, G.; Sidebottom, C. Implementing Mental Health Promotion: The Act–Belong–Commit Mentally Healthy WA Campaign in Western Australia. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2006, 8, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.M. Addressing the determinants of positive mental health: Concepts, evidence and practice. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2009, 11, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrman, H.; Jane-Llopis, E. Mental health promotion in public health. Promot. Educ. 2005, 12 (Suppl. 2), 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jane-Llopis, E.; Barry, M.M. What makes mental health promotion effictive. IUHPE 2005, 2, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Civilstyrelsen. Sundhedsloven—Bekendtgørelse af Sundhedsloven. Available online: https://www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/R0710.aspx?id=210110#ida93f3b5f-d9a3-41b4-a578-67e11fdeb0f3 (accessed on 19 April 2020).

- Ministry of Health. Healthcare in Denmark—An Overview; Ministry of Health: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Friis-Holmberg, T.; Christensen, A.I.; Zinckernagel, L.; Petersen, L.S.; Rod, M.H. Kortlægning. Kommunernes Arbejde Med Implementering af Sundhedsstyrelsens Forebyggelsespakker; Center for Intervention Research, The Danish National Institute of Public Health: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, N.S.; Holmberg, T.; Hærvig, K.K.; Christensen, A.I.; Rod, M.H. Kortlægning: Kommunernes Arbejde Med Implementering af Sundhedsstyrelsens Forebyggelsespakker 2015. Udvikling i Arbejdet fra 2013–2015; Center for Interventionsforskning: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Santini, Z.I.; Koyanagi, A.; Tyrovolas, S.; Haro, J.M.; Donovan, R.J.; Nielsen, L.; Koushede, V. The protective properties of Act-Belong-Commit indicators against incident depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment among older Irish adults: Findings from a prospective community-based study. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 91, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santini, Z.I.; Nielsen, L.; Hinrichsen, C.; Tolstrup, J.S.; Vinther, J.L.; Koyanagi, A.; Donovan, R.J.; Koushede, V. The association between Act-Belong-Commit indicators and problem drinking among older Irish adults: Findings from a prospective analysis of the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 180, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santini, Z.I.; Nielsen, L.; Hinrichsen, C.; Meilstrup, C.; Koyanagi, A.; Haro, J.M.; Donovan, R.; Koushede, V. Act-Belong-Commit Indicators Promote Mental Health and Wellbeing among Irish Older Adults. Am. J. Health Behav. 2018, 42, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittelmark, M.B.; Bauer, G.F. The Meaning of Salutogenesis. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis; Mittelmark, M.B., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Bauer, G.F., Pelikan, J.M., Lindström, B., Espnes, G.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Koushede, V. Mental Sundhed til Alle—ABC i Teori og Praksis; SIF’s Forlag: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, L.; Sørensen, B.B.; Donovan, R.J.; Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T.; Koushede, V. ‘Mental health is what makes life worth living’: An exploration of lay people’s understandings of mental health in Denmark. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2017, 19, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 373–374. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S. Transcribing Interviews. In Doing Interviews; Kvale, S., Ed.; Sage Publications, Ltd.: London, UK, 2011; pp. 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.; McCluskey, S.; Turley, E.; King, N. The Utility of Template Analysis in Qualitative Psychology Research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2015, 12, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justensen, L.; Mik-Meyer, N. Kvalitative Metoder i Organisations-og Ledelsesstudier, 1st ed.; Heinskou, M.B., Ed.; Hans Reitzels Forlag: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar-McHenry, J.; Donovan, R.J.; Nicholas, A.; Kerrigan, S.; Francas, S.; Phan, T. Implementing a Mentally Healthy Schools Framework based on the population wide Act-Belong-Commit mental health promotion campaign. Health Educ. 2016, 116, 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalleh, G.; Donovan, R.J.; James, R.; Ambridge, J. Process evaluation of the Act-Belong-Commit Mentally healthy WA campaign: First 12 month data. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2007, 18, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, M.M.; Domitrovich, C.; Lara, A. The implementation of mental health promotion programmes. Promot. Educ. Suppl. 2005, 2, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekornes, S.; Hauge, T.E.; Lund, I. Teachers as mental health promoters: A study of teachers’ understanding of the concept of mental health. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2012, 14, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, A.; Davis, A. Community development as mental health promotion: Principles, practice and outcomes. Community Dev. J. 2012, 47, 506–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauscher, A.B.; Ardiles, P.; Griffin, S. Building mental health promotion capacity in health care: Results from Phase I of a workforce development project. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2013, 15, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzer, K.R.; Rickwood, D.J. Teachers’ and coaches’ role perceptions for supporting young people’s mental health: Multiple group path analyses. Aust. J. Psychol. 2015, 67, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamminen, N.; Solin, P.; Barry, M.M.; Kannas, L.; Stengård, E.; Kettunen, T. A systematic concept analysis of mental health promotion. International Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2016, 18, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jane-Llopis, E.; Katschnig, H.; McDaid, D.; Wahlbeck, K. Supporting decision-making processes for evidence-based mental health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 2011, 26 (Suppl. 1), i140–i146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachrach, C.; Newcomer, S.F. Addressing bias in intervention research: Summary of a workshop. J. Adolesc. Health 2002, 31, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley-Tyler, M. A Fundamental Choice: Internal or External Evaluation? Eval. J. Australas. 2005, 4, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, B.B. Beyond being an evaluator: The multiplicity of roles of the internal evaluator. New Dir. Eval. 2011, 2011, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Health Report 2001: Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtinen, V.; Ozamiz, A.; Underwood, L.; Weiss, M. The Intrinsic Value of Mental Health. In Promoting Mental Health—Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice; Herrman, H., Saxena, S., Moodie, R., Eds.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005; pp. 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- EU. European Framework for Action on Mental Health and Wellbeing. In Proceedings of the EU Joint Action on Mental Health and Wellbeing—Final Conference, Brussels, Belgium, 21–22 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Item | Variable | Questionnaire Item | Response Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual level | |||

| 1.1 | Overall benefit | Participation in the ABC partnership has been beneficial for me as an employee. | 1 = Fully disagree, 2 = Partly disagree, 3 = Neither agree nor disagree, 4 = Partly agree, 5 = Fully agree, 0 = Not relevant |

| 1.2 | Knowledge about MHP | Through the ABCs of mental health, I have gained knowledge about what to focus on if I want to work with mental health and mental health promotion. | |

| 1.3 | Awareness of relationship between MHP and professional tasks | My knowledge about the ABCs of mental health has made me reflect on how mental health and mental health promotion is related to my work. | |

| 1.4 | Increased awareness, personal mental health (mind-set) | My knowledge about the ABCs of mental health has made me think more about my own mental health. | |

| 1.5 | Behaviour change, personal mental health | My knowledge about the ABCs of mental health has made me actively do something for my personal mental health. | |

| 1.6 | Behaviour change, talking about the ABCs | I have talked about the ABCs of mental health with … (multiple answers allowed) | a) Colleagues, b) Collaborators from other organisations, c) Friends, d) Family, e) Others, f) None |

| Organisational level | |||

| 2.1 | Overall benefit | It has been beneficial for my organisation to be a partner in the ABC partnership. | 1 = Fully disagree, 2 = Partly disagree, 3 = Neither agree nor disagree, 4 = Partly agree, 5 = Fully agree, 0 = Not relevant |

| 2.2 | Relevant framework for MHP | The ABCs of mental health offers a relevant framework for understanding and working with mental health promotion in my organisation. | |

| 2.3 | Mutual language for external collaboration | Through the ABCs of mental health, we have obtained a mutual language for mental health which makes it easier to collaborate on mental health promotion initiatives with external collaborators. | |

| 2.4 | Mutual language for internal collaboration | Through the ABCs of mental health, we have obtained a mutual language for mental health which makes it easier to collaborate on mental health promotion initiatives within my organisation. | |

| 2.5 | Usage of ABC-framework by employees/volunteers | The ABCs of mental health is being used by employees/volunteers in my organisation. | |

| 2.6 | Increased focus on MHP | The work with the ABCs of mental health has sharpened our focus on protective factors and positive aspects of mental health. | |

| 2.7 | Initiation of new initiatives | In my organisation, we have initiated new activities or initiatives which would not have been developed without being involved in or knowing about the ABCs of mental health. | |

| 2.8 | Modifications and changes in existing initiatives | Knowing about the ABCs of mental health has resulted in changes in the focus or aim of existing activities in my organisation. | |

| Characteristic | Category | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| N | 41 | |

| Type of organisation | Municipality | 23 (56) |

| NGO | 10 (24) | |

| Unions | 3 (7) | |

| Other | 5 (12) | |

| Year of involvement with the implementation of the ABCs | 2015 | 1 (2) |

| 2016 | 8 (20) | |

| 2017 | 3 (7) | |

| 2018 | 12 (29) | |

| 2019 | 17 (41) | |

| Primary field of professional interest a | Health | 29 (71) |

| Culture | 9 (22) | |

| Senior | 7 (17) | |

| Social service | 9 (22) | |

| Non-profit | 3 (7) | |

| Physical activity | 8 (20) | |

| Volunteer work | 14 (34) | |

| Other | 6 (15) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hinrichsen, C.; Koushede, V.J.; Madsen, K.R.; Nielsen, L.; Ahlmark, N.G.; Santini, Z.I.; Meilstrup, C. Implementing Mental Health Promotion Initiatives—Process Evaluation of the ABCs of Mental Health in Denmark. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5819. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165819

Hinrichsen C, Koushede VJ, Madsen KR, Nielsen L, Ahlmark NG, Santini ZI, Meilstrup C. Implementing Mental Health Promotion Initiatives—Process Evaluation of the ABCs of Mental Health in Denmark. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(16):5819. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165819

Chicago/Turabian StyleHinrichsen, Carsten, Vibeke Jenny Koushede, Katrine Rich Madsen, Line Nielsen, Nanna Gram Ahlmark, Ziggi Ivan Santini, and Charlotte Meilstrup. 2020. "Implementing Mental Health Promotion Initiatives—Process Evaluation of the ABCs of Mental Health in Denmark" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 16: 5819. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165819

APA StyleHinrichsen, C., Koushede, V. J., Madsen, K. R., Nielsen, L., Ahlmark, N. G., Santini, Z. I., & Meilstrup, C. (2020). Implementing Mental Health Promotion Initiatives—Process Evaluation of the ABCs of Mental Health in Denmark. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5819. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165819