Examining the Moderation Effect of Political Trust on the Linkage between Civic Morality and Support for Environmental Taxation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Civic Morality and Support for Environmental Taxation

3. Moderating Role of Political Trust on the Linkage between Civic Morality and Support for Environmental Taxation

4. Data and Measurement

4.1. Dependent Variable

4.2. Explanatory Variable

4.2.1. Civic Morality

4.2.2. Political Trust

4.3. Controls

4.4. Measurement Validity

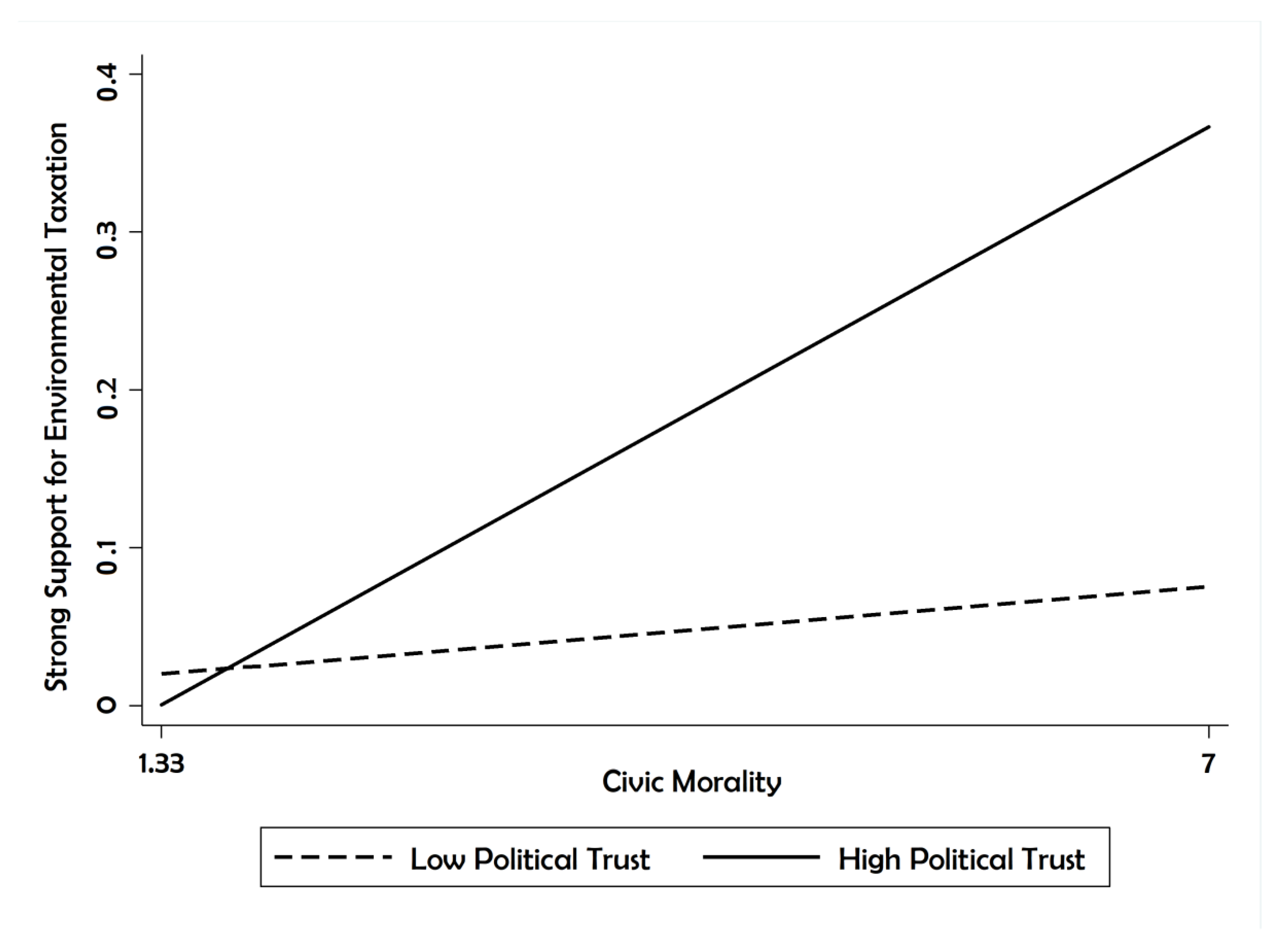

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Global Warming of 1.5 °C: An Ipcc Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C Above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- The End of Australia as We Know it. The New York Times. 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/15/world/australia/fires-climate-change.html (accessed on 16 February 2020).

- Puerto Rico Spend 11 Months Turning the Power Back on. They Finally Got to her. The New York Times 2018. 14 August. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/14/us/puerto-rico-electricity-power.html (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Minder, R. Powerful Winter Storm in Spain kills at least 10. The New York Times. 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/23/world/europe/storm-gloria-spain-floods.html (accessed on 13 March 2020).

- VijayaVenkataRaman, S.; Iniyan, S.; Goic, R. A review of climate change, mitigation and adaptation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 878–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace-Wells, D. The Uninhabitable Earth: Life after Warming; Tim Duggan Books: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod, L.J.; Lehman, D.R. Responding to environmental concerns: What factors guide individual action? J. Environ. Psychol. 1993, 13, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransson, N.; Gärling, T. Environmental concern: Conceptual definitions, measurement methods, and research findings. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S. Environmental concern, attitude toward frugality, and ease of behavior as determinants of pro-environmental behavior intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grob, A. A structural model of environmental attitudes and behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.L.M.; Zint, M.T. Toward fostering environmental political participation: Framing an agenda for environmental education research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 19, 553–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Juknys, R. The role of values, environmental risk perception, awareness of consequences, and willingness to assume responsibility for environmentally-friendly behaviour: The Lithuanian case. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3413–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, T.P.; Fernandes, R. A re-assessment of factors associated with environmental concern and behavior using the 2010 General Social Survey. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 22, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Effects of values, problem awareness, and personal norm on willingness to reduce personal car use. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, M.J.; Rudolph, T.J. Why Washington Won’t Work: Polarization, Political Trust, and the Governing Crisis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, T.J. Political trust as a heuristic. In Handbook on Political Trust; Zmerli, S., van der Meer, T., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Letki, N. Investigating the roots of civic morality: Trust, social capital, and institutional performance. Polit. Behav. 2006, 28, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deth, J. Compliance, trust and norms of citizenship. In Handbook on Political Trust; Zmerli, S., van der Meer, T., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 212–227. [Google Scholar]

- Alm, J.; Torgler, B. Culture differences and tax morale in the United States and in Europe. J. Econ. Psychol. 2006, 27, 224–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgler, B. Tax Compliance and Tax Morale: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis; Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc.: Northampton, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dresner, M.; Handelman, C.; Braun, S.; Rollwagen-Bollens, G. Environmental identity, pro-environmental behaviors, and civic engagement of volunteer stewards in Portland area Parks. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 991–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, A. Environmental citizenship: Towards sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagers, S.C.; Martinsson, J.; Matti, S. Ecological citizenship: A driver of pro-environmental behaviour? Environ. Polit. 2014, 23, 434–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojea, E.; Loureiro, M. Altruistic, egoistic and biospheric values in willingness to pay (WTP) for wildlife. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 63, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, T.; Popp, E. Bringing the ideological divide: Trust and support for social security privatization. Polit. Behav. 2009, 31, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, M. Why Trust Matters: Declining Political Trust and the Demise of American Liberalism; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi, H.; Marshall, G.A. Trust, political orientation, and environmental behavior. Environ. Polit. 2018, 27, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbrother, M. Rich people, poor people, and environmental concern: Evidence across nations and time. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 29, 910–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harring, N. Understanding the effects of corruption and political trust on willingness to make economic sacrifices for environmental protection in a cross-national perspective. Soc. Sci. Q. 2013, 94, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harring, N. Trust and state intervention: Results from a Swedish survey on environmental policy support. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 82, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.K.; Mayer, A. A social trap for the climate? Collective action, trust and climate change risk perception in 35 countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 49, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orviska, M.; Hudson, J.W. Tax evasion, civic duty and the law abiding citizen. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 2002, 19, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deth, J. Norms of citizenship. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior; Dalton, R.J., Klingemann, H.D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 402–417. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, R. Citizenship norms and the expansion of political participation. Polit. Stud. 2008, 56, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T. Why People Obey the Law; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, A.L.; Videras, J. Civic cooperation, pro-environment attitudes, and behavioral intentions. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 58, 814–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citrin, J. Comment: The political relevance of trust in government. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1974, 68, 973–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H. Political issues and trust in government: 1964–1970. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1974, 68, 951–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanley, V.A.; Rudolph, T.J.; Rahn, W.M. The origins and consequences of public trust in government. Public Opin. Q. 2000, 64, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, M. The political relevance of political trust. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1998, 92, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, M.J.; Globetti, S. Political trust and racial policy preferences. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 2002, 46, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, M.J.; Husser, J.A. How trust matters: The changing political relevance of political trust. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 2012, 56, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, M.J.; Rudolph, T.J. Priming, performance, and the dynamics of political trust. J. Polit. 2008, 70, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, E.; Rudolph, T.J. A tale of two ideologies: Explaining public support for economic interventions. J. Polit. 2011, 73, 808–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, T.; Evans, J. Political trust, ideology, and public support for government spending. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 2005, 49, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, T.J. Political trust, ideology, and public support for tax cuts. Public Opin. Q. 2009, 73, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbing, J.R. What Is It About Government that Americans Dislike? Hibbing, J., Theiss-Morse, E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Keele, L. Social capital and the dynamics of trust in government. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 2007, 51, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiken, S. Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 752–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiken, S.; Trope, Y. (Eds.) Dual-Process Theories of Social Psychology; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S.T.; Taylor, S.E. Social Cognition, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hooghe, M.; Zmerli, S. Introduction: The context of political trust. In Political Trust: Why Context Matters; Zmerli, S., Hooghe, M., Eds.; ECPR Press: Colchester, UK, 2011; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kang, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, C.; Park, W.; Lee, Y.; Choi, S.; Kim, S. Korean General Social Survey 2003–2016; Sungkyunkwan University: Seoul, South Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wanous, J.P.; Reichers, A.E.; Hudy, M.J. Overall job satisfaction: How good are single-item measures? J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanous, J.P.; Hudy, M.J. Single-Item reliability: A replication and extension. Organ. Res. Methods 2001, 4, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Robinson, R.B. Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: The case of the privately-held firm and conglomerate business unit. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, S.E. Reciprocal effectis of participation and political efficacy: A panel analysis. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 1985, 29, 891–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, P.H. The participatory consequences of internal and external political efficacy: A research note. West. Polit. Q. 1983, 36, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.; van Wessel, M.; Maeseele, P. Communication practices and political engagement with climate change. Environ. Commun. 2017, 11, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schild, R. Fostering environmental citizenship: The motivations and outcomes of civic recreation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018, 61, 924–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.C.; Waliczek, T.M.; Zajicek, J.M. Relationship between environmental knowledge and environmental attitude of high school students. J. Environ. Educ. 1999, 30, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, M.; Karami, E. Farmers’ pro-environmental behavior under drought: Application of protection motivation theory. J. Arid Environ. 2016, 127, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jeong, S.-H.; Hwang, Y. Predictors of pro-environmental behaviors of American and Korean students: The application of the theory of reasoned action and protection motivation theory. Sci. Commun. 2012, 35, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, B.; Kang, B. South Korea Joins Ranks of World’s Most Polluted Countries. Financial Times, 29 March 2017. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/b49a9878-141b-11e7-80f4-13e067d5072c (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- McCright, A.M. The effects of gender on climate change knowledge and concern in the American public. Popul. Environ. 2010, 32, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiernik, B.M.; Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Age and environmental sustainability: A Meta-analysis. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 28, 826–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A. Heterogeneity in the preferences and pro-environmental behavior of college students: The effects of years on campus, demographics, and external factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3451–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S. South Koreans Rally in Largest Protest in Decades to Demand President’s Ouster. The New York Times, 12 November 2016. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/13/world/asia/korea-park-geun-hye-protests.html (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Choi, S. South Korea Removes President Park Geun-hye. The New York Times, 9 March 2017. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/09/world/asia/park-geun-hye-impeached-south-korea.html (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Pew Research Center. Little Public Support for Reductions in Federal Spending. 11 April. Available online: https://www.people-press.org/2019/04/11/little-public-support-for-reductions-in-federal-spending/ (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Lee, J. South Korea’s Moon Sees Approval Rating Hit New Low Amid Scandal. Bloomberg, 18 October 2019. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-10-18/south-korea-s-moon-sees-approval-rating-hit-new-low-amid-scandal (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Shin, H. Ratings of South Korea’s Moon Take a Hit from Virus Outbreak. Reuters. 28 February 2020. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-health-southkorea-moon/ratings-of-south-koreas-moon-take-a-hit-from-virus-outbreak-idUSKCN20M0RK (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- McCurry, J. South Korea’s Ruling Party Wins Election Landslide Amid Coronavirus Outbreak. The Guardian. 16 April 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/16/south-koreas-ruling-party-wins-election-landslide-amid-coronavirus-outbreak (accessed on 16 April 2020).

| Variables | N | Mean | S.D. | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support for environmental taxation | 760 | 3.33 | 1.10 | 1 | 5 |

| Civic morality | 760 | 5.57 | 1.01 | 1.33 | 7 |

| Political trust | 760 | 1.45 | 0.46 | 1 | 3 |

| Political participation | 760 | 1.67 | 0.66 | 1 | 4 |

| Political interest | 760 | 2.44 | 0.78 | 1 | 4 |

| Perceived local pollution | 760 | 2.45 | 0.63 | 1 | 4 |

| Perceived environmental threats | 760 | 3.62 | 0.63 | 1.67 | 5 |

| Age | 760 | 44.98 | 13.19 | 18 | 83 |

| Female | 760 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Income | 760 | 6.46 | 4.24 | 0 | 21 |

| Education | 760 | 4.00 | 1.39 | 0 | 7 |

| Variables | Support for Environmental Taxation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | |||

| Coef. | (S.E.) | Coef. | (S.E.) | |

| Civic morality | 0.19 | 0.05 *** | −0.11 | 0.13 |

| Political trust | 0.24 | 0.09 *** | −0.98 | 0.48 ** |

| Civic morality × political Trust | 0.22 | 0.08 *** | ||

| Political participation | 0.25 | 0.07 *** | 0.27 | 0.07 *** |

| Political interest | 0.14 | 0.06 ** | 0.12 | 0.06 * |

| Perceived local pollution | 0.13 | 0.07 * | 0.13 | 0.07 * |

| Perceived environmental threats | 0.16 | 0.08 ** | 0.15 | 0.08 * |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Female | −0.04 | 0.09 | −0.03 | 0.09 |

| Income | 0.02 | 0.01 ** | 0.02 | 0.01 ** |

| Education | 0.08 | 0.03 ** | 0.08 | 0.03 ** |

| τ1 | 2.08 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.82 |

| τ2 | 2.98 | 0.45 | 1.25 | 0.82 |

| τ3 | 3.47 | 0.46 | 1.75 | 0.83 |

| τ4 | 5.17 | 0.47 | 3.46 | 0.83 |

| Log likelihood | −985.82 | −982.53 | ||

| Wald test | 117.68 | 130.83 | ||

| Number of cases | 760 | |||

| Variables | Strong Support for Environmental Taxation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | Difference | |

| Civic morality × political trust | 1.98% | 36.68% | 34.70% |

| Civic morality | 0.89% | 11.68% | 10.79% |

| Political trust | 5.55% | 13.21% | 7.66% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, J.Y.; Moon, K.-K. Examining the Moderation Effect of Political Trust on the Linkage between Civic Morality and Support for Environmental Taxation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4476. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124476

Lim JY, Moon K-K. Examining the Moderation Effect of Political Trust on the Linkage between Civic Morality and Support for Environmental Taxation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(12):4476. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124476

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Jae Young, and Kuk-Kyoung Moon. 2020. "Examining the Moderation Effect of Political Trust on the Linkage between Civic Morality and Support for Environmental Taxation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 12: 4476. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124476

APA StyleLim, J. Y., & Moon, K.-K. (2020). Examining the Moderation Effect of Political Trust on the Linkage between Civic Morality and Support for Environmental Taxation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4476. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124476