4.1. The Livelihood Fragility Problem Faced by Left-Behind Women

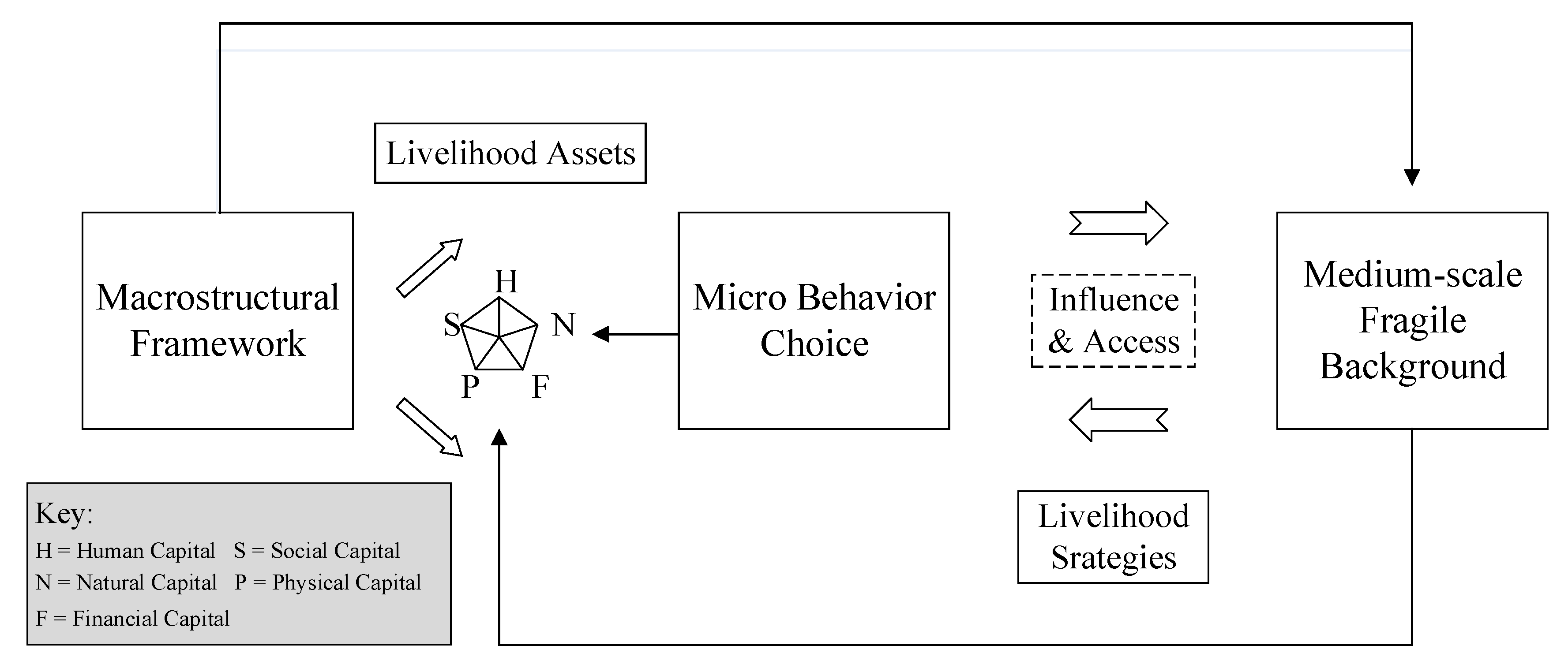

Among the elements of the concept of livelihood, livelihood capital occupies the core position. Therefore, livelihood capital is basically used as an evaluation index in academia. In this research, the separation phenomenon of rural left-behind families leads to some constraints in family structure and function, which makes left-behind women face the plight of livelihood fragility, which is manifested in the following five types of livelihood fragility.

The ideological germination of social capital can be traced back to Durkheim’s “collective consciousness” and Zimmer’s “reciprocal exchange”. However, as a theory, it began with the study of Bourdieu, Parson, and others. After Coleman’s theoretical definition of social capital, Putnam, Porter, and some others, further developed the theory of social capital. In the DFID framework, social capital represents the social resources that people can use in the pursuit of livelihood goals. After the husband moves away for work, the left-behind wives in the countryside have to adapt from being the “housewife” to functioning as the “backbone” of the family. They have to shoulder all the family responsibilities that were originally shared by the husband as well, and also have to deal with the resulting physiological and psychological pressure. Although these women often feel powerless, they are afraid to seek help from other males. The rural society is an acquaintance society. The closeness and traditions of the society are very strict regarding the role of women and their morality. Consequently, left-behind women have to avoid any gossip that could connect them with other men. According to the survey, 26.4% of the left-behind women were the subject of gossip while their husbands were away (among these left-behind women, 75.4% were between 31 and 50 years old, 94% gave birth to one or two children, 61.4% were separated from their husbands for more than six months, and 64.8% of these families had the per capita annual income of less than 5000 RMB) (

Appendix A). Mrs. Wang’s experience illustrates the embarrassing social interaction dilemma of these women:

Mrs. Wang, whose husband went to work in the city after she gave birth to their second child, had to take on the farm work, while also taking care of her parents-in-law and her two children. During the agricultural season, she can only ask relatives or neighbors for help, because she is afraid that people would gossip about her if she asked other men for help

(personal communication).

The production process of social capital is a process of communication and connection between people, people and organizations, and organizations and organizations. The scope of social contact of left-behind women is limited, and is only based on blood and geographic relationship that is maintained between relatives and neighbors. The concept of “virilocal marriage” also weakens, or even breaks down, the existing social network of left-behind women, and their social scope presents an “involution” situation. Additionally, 92.5% of the left-behind women have to engage in agricultural production, and also spend an average of 5.71 h a day in family care and support. This undoubtedly further restricts their participation in public life and affects their social activities. This participation is not only a wake-up call to expand political participation, but also an important way and means to accumulate social capital. Left-behind women have no time to cross-examine politics and their capacity to contribute toward social capital is also reduced because of over-involvement with the family and poor social capital. However, there is no denying that left-behind women are the link between urban and rural areas. The husband shares the stories in the city with his wife, and then the left-behind woman shares them with relatives in the rural home, which promotes the communication between the husband and the rural family.

In the 1950s, American economists Sehultz and Becker regarded personal education and vocational training as an investment, which would form personal “human capital”. In the DFID framework, human capital represents knowledge, skills, abilities, and health status. These are means for people to pursue and achieve different livelihood goals. The questionnaire survey shows that 96.1% of the left-behind women have children, which implies that taking care of them and educating them becomes their responsibility. However, only 16.8% of these women have high school diplomas or higher education. Consequently, these women cannot support the education of their children adequately, hence, 61.9% of these women are concerned about the learning of their children. Furthermore, only 5.8% of these women often participate in training on children’s education. The lack of education and the cultural background also affects their ability to grasp information related to agricultural science and technology. Consequently, they cannot be a part of the agricultural technology team and can only engage in traditional manual labor which offers low added value. Mrs. Zhao’s attitude reflects the lack of understanding science and technology by left-behind women:

Mrs. Zhao, a left-behind woman with only junior high school education, ploughs seven acres of land by herself. She thought that this work was very hard and did not understand the new technologies that could be used for ploughing. Also, she did not want to try using new technologies or new methods, as she was afraid that she would not be able to deal with the loss if she made a mistake

(personal communication).

Playing the role of “both housewife and backbone” not only made it difficult for these women to have the energy, time, and motivation to participate in agricultural technology training, but also immensely increased the pressure on them and, hence, led to physiological and psychological problems. The surveys and interviews reveal that continuous physical labor, especially when there were children to take care of, was having an adverse impact on the health of these women. Sixty-four percent of these women stated that their physical health is not ideal. However, most of these women ignore their health and do not get treatment as is needed. This is evident from the fact that 44.6% of these women do not meet a doctor when needed. Only when they did not have a choice, 54.6% of them chose to see a doctor. The family economic conditions of these left-behind women were generally poor, the survey data shows that more than 65% of these families had the per capita annual income of less than 5000 RMB. As the pillar of the left-behind family and the main force of rural daily production and life, their health problems do not only have an impact on just themselves but also on the entire family and even the rural society. The following case illustrates the health risks associated with their attitude:

Mrs. Xu is a left-behind woman, and she is always busy with housework and agricultural work, hence her health suffers. She often buys medicines from the village peddler, which functions as an informal pharmacy. She says, “The medicines are quite cheap, and it saves me the trouble of going outside the village. At least this medicine helps a bit, this is better than taking no medicine at all”

(personal communication).

In the framework of DFID, financial capital is the accumulation and flow that people require to fulfill their livelihood goals through the process of production and consumption. It refers to money, as well as to the physical objects that can play a role in the accumulation and exchange of money [

11]. Jin et al. (2011) defined financial capital as available savings and regular capital inflows [

23]. A lot of rural labor force has been shifting to the cities, since the 1980s and the trend of masculinity implies that a large number of women stay in the countryside, as the original, “male farming and women weaving” division of labor in the family has been gradually replaced by “male working and women farming”, and the phenomenon of the feminization of agriculture is becoming increasingly common. However, this cannot be precisely termed as the feminization of agriculture as women’s agriculturalization, because in reality it is a situation of “women working while men manage”, and the decision-making power regarding agricultural production and operations is still controlled by men. In this survey, 68.5% of the left-behind women could not make important decisions pertaining to the family, agricultural production, and life independently. Even though 61.4% of these left-behind women had been separated from their husbands for more than six months, they still could not make important decisions at home and in their agricultural activities (

Appendix A).

Additionally, the relative weakness of the agricultural economy makes the family contribution rate of the left-behind women also decline. According to the survey data, 80% of the left-behind women accounted for less than 40% of the total household income, and 44.2% of the left-behind women accounted for less than 20% of the total household income (

Appendix A). Even if about 30% of these left-behind families had the per capita annual income of more than 5000 RMB, the family economic contribution of the left-behind women was still quite limited. Additionally, as the husbands do not live with the family and the women have limited time and energy, the lack of a proper educational environment is expected to have a negative impact on the behavior and values of left-behind children. Taking this into consideration, most left-behind women consciously spend more time and energy on their children. Survey data indicates that the average time spent on housework by these women is 2.47 h per day, the time for educating their children is 1.68 h per day, and for caring for the elderly is 1.56 h per day. However, as women are not remunerated for the housework, their contribution is neglected.

In the DFID framework, material capital includes infrastructure that is required to support basic livelihoods. Jin et al. (2011) regard communication and information services that farmers can afford, as material capital [

23]. As the level of education of left-behind women is low, it is difficult for them to update their internalized agricultural knowledge and master new agricultural technology, which affects their income-generating ability. This ability is also restricted as the women do not possess the skills to collect and analyze information. According to the survey, there are limited channels for left-behind women to obtain information and consequently, 45.3% of these women urgently need market information services. This could also be attributed to the fact that these women have limited free time and energy to collect and analyze information. Additionally, they do not know how to use media to obtain information, and it is difficult for them to grasp the market information in time. Consequently, they cannot meet the production requirements effectively according to the market demand, and miss out on the opportunity to make a profit (in reality, agricultural products have another destinations except for the big markets, that are, self-sufficiency or in local markets, and that even account for a large proportion. However, women have no, or just a little remuneration, for this part, so their contribution is always neglected).

Due to the formation of the agricultural production labor market and the help of relatives, the agricultural production responsibilities undertaken by left-behind women have been reduced, but they still feel powerless when faced with temporary and sudden heavy manual labor. Additionally, Ren et al. (2011) believe that material capital primarily includes housing and family-owned facilities and equipment [

24]. Most rural houses are relatively independent and far away from each other, and many of them have low courtyard walls and small gates. Criminals can easily enter the courtyard, which gives them easy access to the houses. Additionally, the outflow of the young male labor force from these areas has weakened the public security system. The physical and property security of left-behind women is vulnerable to infringement and this increases their psychological burden. These women are afraid of being alone at night because of the unsafe living environment in the countryside. Some of them even sleep with the TV set on as they are afraid of sleeping without any light or sound. The lack of material capital led to Mrs. Chen’s misfortune:

Mrs. Chen lived alone with her three-year-old daughter and one-year-old son. On the night of the incident, Mr. Li intended to only steal, but when he realized that Mrs. Chen and the two children were alone at home, he raped Mrs. Chen. Mrs. Chen did not inform her husband or the police because she was worried that her husband would file for a divorce and she was also afraid that she would be discriminated against by others

(personal communication).

Natural capital refers to the storage of natural resources and environmental services from which livelihood-friendly resources can flow and services can be derived. Presently, China’s per capita arable land area is 1.5 acres, however, the population has increased by 1.4 times, which implies that, in the absence of significant improvement in production conditions, there will inevitably be a conflict because of more people and less land. When a large portion of the male labor force in rural areas gives up working in the agricultural field, it eases the pressure on the family to a certain extent, and makes the left-behind women the backbone of agricultural production. However, because of the disintegration of the people’s commune, the focus on the construction of farmland and water conservation has decreased. This also makes it difficult to concentrate human, material, and financial resources on large-scale construction of farmland and water conservation facilities, and then the original farmland and water conservation facilities are not maintained or even suffered human destruction. In order to maintain normal agricultural production, much manual labor must be invested to meet the needs of land irrigation, however, due to the inherent physical disadvantages of left-behind women, they may not be able to afford the heavy manual labor, which makes it difficult for agricultural production to resist natural disasters due to the weakening of the protection. Consequently, agricultural families may fall into poverty (although economic remittances from husbands who have gone to work in urban cities have a significant contribution to improving the family’s economic situation, only a part of the rural families can get rid of poverty. For more rural families, on one hand, due to the high cost of living in the city, not all income of husbands can be sent home. On the other hand, children’s education and medical treatments require a great deal of money, which often leads to family expenditures greater than family income, and ultimately the families still have difficulty getting out of poverty).

The society in the rural areas in China is still largely agriculture centered. Land resources and property rights system regulate the process of the traditional society moving toward becoming a modern society. As Du (2005) said, “Land reform lays the foundation of today’s rural areas” [

25]. With increasing modernization, comprehensive rural reforms in China are faced by a dilemma, and conflicts of interest have intensified. Amongst these, gender discrimination in rural land allocation has gradually changed from being recessive to explicit. This is visible on two axes [

26], which are centered on gender identity, targeted at rural women and characterized by the deprivation of gender land rights and interests. This is manifested as rural women’s right to land contractual management, the right to use residential land, the income of collective economic organizations, and the right to allocate land expropriation compensation fees, being infringed [

27]. Left-behind women who are categorized as exogamy women are facing the dilemma of “two ends empty” that “their mother’s land is recovered and their mother-in-law’s land is not available to them”. Some of them cannot claim the right to contract in their mother’s family, and some lose the right to contract and manage because of divorce and widow remarriage. Mrs. Zheng is one of them who had to deal with this awkward situation after she got married:

When Mrs. Zheng, a left-behind woman, submitted an application for land for personal housing due to demolition and reconstruction, she was refused and she was informed that she could not be included in her parent’s residence registration anymore because she was married. At the same time, her husband had not registered her name either

(personal communication).

4.2. Macro-Structure Framework: Modernization Construction with Unsynchronized Development of Industrialization, Informatization, Urbanization, and Agricultural Modernization

As an external policy environment, livelihood system includes the entire process of livelihood capital production, livelihood strategy selection, and livelihood outcome output. The scattering of rural left-behind families is the response of farmers to the asynchronous modernization of industrialization, informatization, urbanization, and agricultural modernization, and the result of the choice of family livelihood strategies of the husband going out while the wife stays back. The essence is that some vulnerable groups are forced to break away from the mainstream of development. This is the negative spillover effect of the state’s attempt to rapidly build industrial modernization through the effective use of limited public resources.

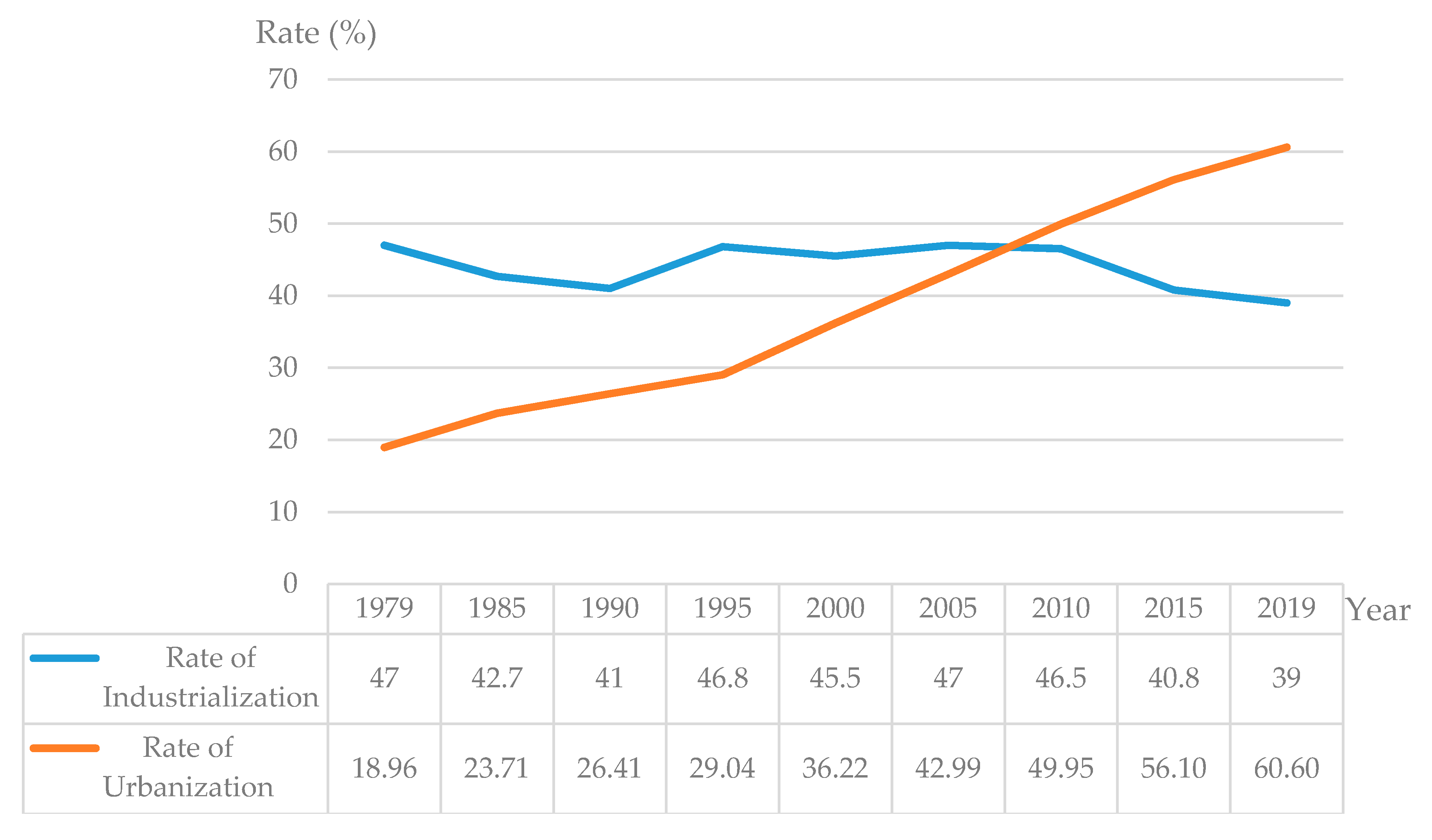

First, the relatively slow urbanization compared to the pace of industrialization inhibits cities from providing a conducive environment for the migration of the entire family rather than just the migrant workers. China’s modernization with industrialization began in 1949. To ensure the smooth progress of modernization with industrialization as the core, the state established certain urban preferential policies with the household registration system as the core content. To begin, these are intended to build a good social order, and then gradually evolve into an important means of social control, resource allocation, and benefit redistribution, to prevent the large-scale flow of rural labor force. This leads to the stagnation of the movement of rural labor force and the process of urbanization. The rate of urbanization has gradually increased from 10.64% in 1949 to 17.92% in 1978. After 1949, as the country vigorously promoted the household registration system and relaxed the requirements of the household registration migration policy, large-scale rural labor began to relocate to cities and towns, and the urbanization rate increased significantly. In spite of this, a very large gap still exists when compared with the long-term industrialization rate of about 45% (

Figure 3). The rate of urbanization has been lagging behind industrialization for a long time, and this makes it difficult for cities to provide infrastructure and basic public services for migrant workers, and forces them to move between urban and rural areas in the form of family separation

Second, the disharmony between urbanization and agricultural modernization lead to low agricultural comparative benefits and imbalanced urban-rural public services. Although “industry feeds back agriculture, city feeds back countryside” is now a consensus, it has not fundamentally changed the interest pattern of unbalanced industrial and agricultural development and has distorted urban-rural market relations in China. This symbiotic state of preference has two impacts. First, agricultural economic income is relatively low as the economic added value of agriculture is far less than that to the industry and service industry, it is difficult for farmers to earn a higher income solely from traditional agricultural production. The income gap between urban and rural areas in China has gradually widened since 1978. By 2017, the ratio of disposable income between urban and rural residents had reached 2.71. To address the economic interests, the movement of rural labor force to cities is inevitable. Second, the basic public services in rural areas are not well established. The long-term implementation of the “agriculture supporting industry, rural supporting urban”, development method has led to a lag in the development of rural infrastructure and basic public services. Due to the lack of a proper supply system for rural family production and life care services, migrant workers can only rely on their own human capital to address the lack. Therefore, based on the strategy of “working in cities and farming in countryside” and the necessity of family care, wives continue living in the countryside to take care of the families and agricultural production, while husbands have to leave the home to work in cities and towns.

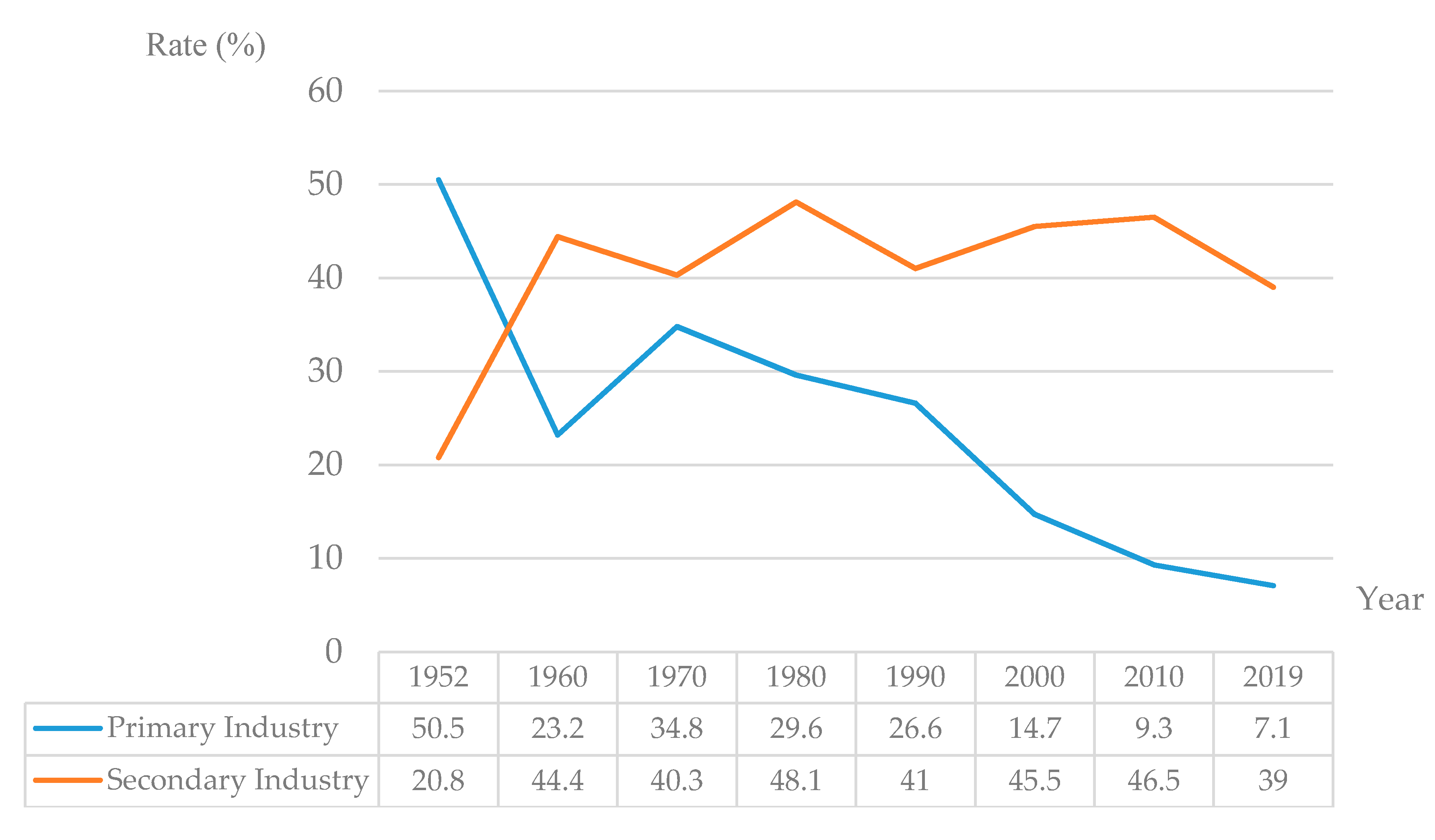

Third, the lag in agricultural modernization as compared to industrialization makes it difficult for rural laborers to work in their hometown. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the national strategy of priority development of heavy industry was implemented. Industrial development funds were accumulated through the “scissors gap” price of industrial and agricultural products, and raw material needed for industrial development were continuously drawn from agriculture. After 1979, the rural surplus labor force, got the opportunity to move to the city. As industries drew a large number of cheap laborers from agriculture they made great progress. From that time on, the positioning of agriculture and industry in the national economy has undergone tremendous changes. In 1952, the primary industry accounted for 50.5% of the GDP, which implied that it was a dominant part of the national economy. By 2019, the proportion had dropped to 7.1 percent. Conversely, the proportion of secondary industry in GDP in 1952 was 20.8%, and it rose to 39% in 2019 (

Figure 4). Agricultural modernization and industrialization have existed in this parasitic state for a long time, which implies that industrialization is not strong enough to drive agricultural modernization and rural industrialization, and the ability of rural surplus labor work force to transfer directly to secondary and tertiary industries is limited. Driven by comparative interests and rational choice of urban and rural employment, a large number of rural labor work force flowed into cities, resulting in the abnormal structure of the “separation” of rural families.

Fourth, the ubiquitous and parasitic nature of information technology enables its integration with industrialization, agricultural modernization, and urbanization, and it acts as a symbiotic interface for material, information, and energy exchange between the other “three modernizations” and the external environment [

28]. However, due to the insufficient development of informationization and its insufficient integration with the “three modernizations”, it is difficult to promote them to the advanced stage of development based on information resources, driven by knowledge innovation and carried by the Internet, so that urbanization and industrialization have insufficient driving effect on agricultural modernization. Agricultural informationization can reduce agricultural water consumption by 30–70% and improve land use efficiency by more than 10% by adopting precise water-saving irrigation technology [

29]. Additionally, the soil moisture in the topsoil can be improved, and winter wheat yield can be promoted by adopting laser-controlled land leveling technology [

30]. However, the integration of informationization and agricultural modernization in China is insufficient, and the level of informationization is relatively low. It is still at the early stage of growth [

31]. As stated previously, the asynchronization of industrialization, urbanization, and agricultural modernization has led to the separation of rural left-behind families. However, the lack of integration of informatization and the other three modernizations aggravates the asynchronization of the development of industrialization, informatization, urbanization, and agricultural modernization, which indirectly has in impact on the separation of rural left-behind families.

4.3. Medium-Scale Fragile Background: The Social Modernization Process of Continuously Weakening Families

In the DFID framework, fragility background refers to the external livelihood environment that people have to deal with, which fundamentally affects their livelihood and the available livelihood capital, especially the economic benefits of their livelihood activities and the corresponding choices. In the process of social modernization, the values of family reunions are undermined, there is a negative impact on the traditional organization of family relationships, and it disintegrates the normal functions of family. Consequently the traditional gender differences in rural areas and the urban-rural dual household registration system jointly resulting in the families of farmers rationally making a choice regarding the livelihood strategies based on gender differentiation and migration based on family decentralization. Women are forced to stay in the countryside and have to deal with the resulting livelihood fragility alone.

First, the family spirit is the Constitutional spirit of China, but the process of social modernization is a process that constantly impacts the traditional family consciousness [

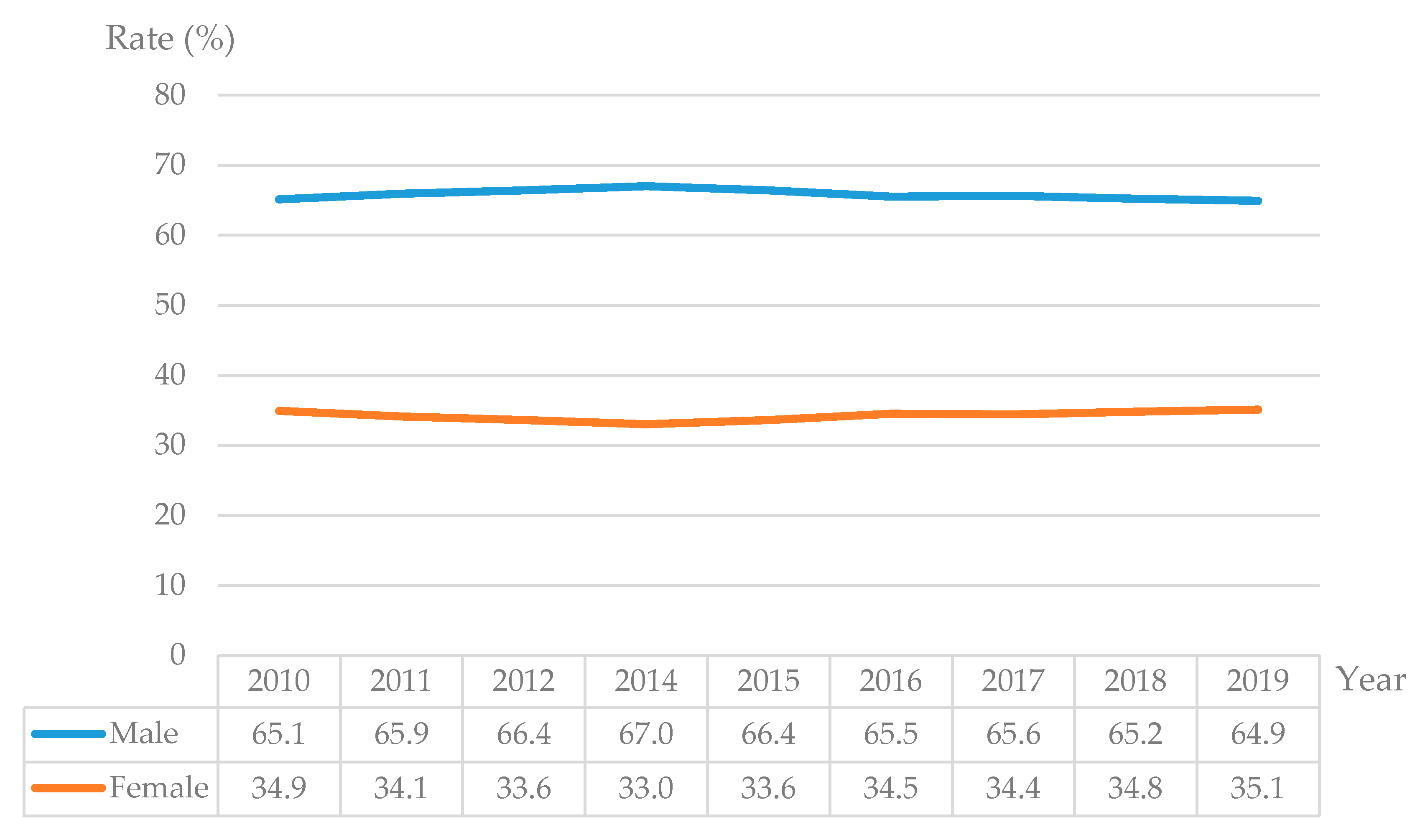

32]. From the Revolution of 1911, the New Cultural Movement to the May 4th Movement, the feudal family system became the critical object of the enlightenment thinkers, and the war and revolutionary idealism in the old and new democratic revolutions even antagonized the family and the country. In the last 30 years the movement from New China to reforms and opening up, social movements have constantly destroyed the traditional family model on an economic basis and ideological level. The extreme politicization of the “Cultural Revolution” lead to excessive harm to the family structure. Just as people dispelled the mistake of trampling on family values during the Cultural Revolution, the tide of reform and opening up swept over. With this, the basic unit of a modern society has been implemented to the greatest extent on independent people. The ideal example of this is the use of urban-rural dual household registration system to screen individualized, non-family-led rural male labor force, and the refusal to grant them citizenship to share urban welfare resources. Consequently, it becomes difficult for families of migrant workers’ families to establish themselves in cities and live and work with peace and contentment. Migrant workers can only migrate to cities in the form of gender differentiation, which is reflected in

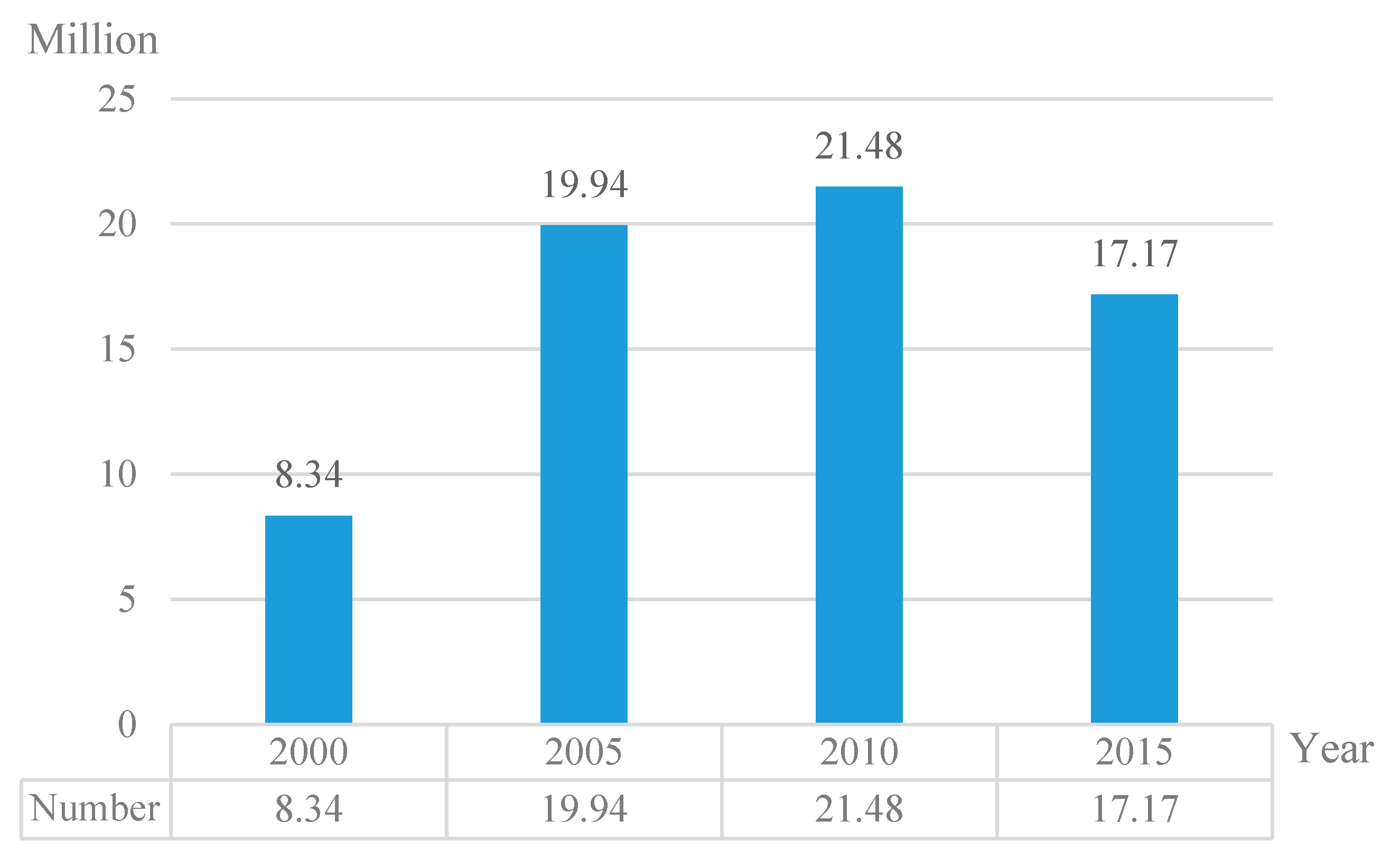

Figure 5:

Second, after the reform and opening up, the individual-based values spread in the society. It became difficult for families which were at the edge of the national vision to become the beneficiaries of system design and arrangement. The function and importance of the family has been increasingly ignored by the society, which lead to a further decline in the value of family in the design and arrangement of the national system. This implies that the basic rights and interests of migrant workers’ families in cities are not guaranteed and their demands are left unsatisfied. In this survey, 70.1% of left-behind women think it is expensive for their husbands to rent a house in cities, and 47.3% think it is expensive for their husbands to see a doctor in cities. Further, only 37.7% of left-behind women said their husbands had work-related injury insurance, 29.1% said their husbands had unemployment insurance, and 18.7% said their husbands had a housing provident fund. This forces migrant workers to attempt to “maximize family interests”. These workers try to avoid risks. Consequently, they have to make rational choices based on gender differentiation and family decentralization. Women are forced to stay alone in the countryside and bear the livelihood fragility caused by family separation. A large number of rural left-behind families and women have become victims of urban construction, and are unable to enjoy the benefits of a complete family.

Third, the current practice of unbalanced modernization of urbanization, industrialization, and agricultural modernization reflects the government’s focus on economy and efficiency. This is essentially a developmental thought process which propagates the thought, “economic growth overwhelms everything” [

33]. This thought process equates modernization with economic development, technological progress, and wealth increase. Public policy also propagates the principle of efficiency first. It responds to the demands of peasants by means of policy tools of management rather than service [

34]. It primarily lays emphasis on the development of a material economy and neglects the value care that people need, and neglects that the fundamental principle of ensuring the well-being of the citizens should be development. This pathological concept of excessive focus on the development of modernity will lead to the development of modernization by overstepping the limited rationality, and will lead to neglecting the needs of people, gender differences, family disintegration, and the rural female labor force would have to live in the countryside to make a living. Village head Li reflected the neglect of left-behind women’s interests in the process of economic development:

Some left-behind women went to work in nearby factories, but most factories did not sign legal labor contracts with left-behind women, nor did they purchase necessary insurance for left-behind women. When left-behind women were injured at work, they only got medical expenses from the factory but no legal insurance compensation

(personal communication).

4.4. Micro-Behavioral Choice: Choice of Family Livelihood Strategies under Social Gender Culture

With the rapid advancement of urbanization in the country and the dual economic and social structure which gradually leads to the integration of urban and rural areas, a series of social security systems, such as the basic pension insurance system and the basic medical insurance system, as an important part of China’s economic and social structural arrangements, are also moving towards integrated development to achieve inclusiveness and equalization of public services. However, in the context of economic growth and over all development, the government focuses on economic development performance and other work that can indicate political achievements, and pays less attention to social equity, especially gender issues, and largely believes that the development goal of gender equity is pursued by a postmodern society. Furthermore, even if gender equity is taken into consideration while formulating policies, most of the focus is on protecting the rights and interests of urban women, and less on rural left-behind women.

Additionally, the livelihood strategies include production activities, investment strategies, and reproduction choices. The livelihood strategies in the farmers’ daily life practice also begin with the psychological framework used to understand the situation. Consciousness cannot be considered without its context, and every situation contributes toward the meaning of accumulation to structure the next moment. To a large extent, life takes place in a world constructed by human beings, where life has historical accumulation, which is an attitude toward the world [

35]. The traditional gender division of labor in China has stereotyped women as being family-oriented, this also gives men priority in resource allocation, and the opportunity to enter the profitable urban industries while women are left behind to handle the unpaid family agriculture.

First, the Chinese traditional gender culture originated from the prevailing Confucian culture of patriarchy which was centered on male superiority and female inferiority. Despite the constant impact of social progress, the pattern of “male working outside, female taking care of home” has become even stronger and can be seen in all sectors of the society. This culture also requires women to regard “traditional virtues” such as “carrying on the ancestral line” and “assisting husband and educating children” as important criteria related to life value [

36]. It requires women to confine their activities and time to address and indulge in trivial family affairs. Traditional gender concepts also endow rural women with psychological characteristics such as inferiority dependence, weakness and timidity, and substitutional achievement motivation. They lack the courage to break through traditional family roles to work in the non-agricultural industries. They are willing to act as housewives and regard the achievements of their husband as the realization of their own values. Survey data shows that 41.1% of the left-behind women agree with the division of “male working outside, female taking care of home”, and 54% of the left-behind women believe that women will encounter more difficulties in working in the city, and then they voluntarily stay at home. Therefore, in the process of urban-rural migration of labor force, the traditional gender concept has an impact on the role image and family expectations. This usually results in the husbands going to the city to work while the wives stay at home.

Second, one of the basic characteristics of Chinese traditional agricultural life is labor intensive cultivation with an iron plough and cattle ploughing as the primary methods. Thus, through the division of labor within the family based on physiology, men take on the labor heavy and intensive field work, while women take on the less intensive housework, forming a division of labor mode of “male cultivating and female weaving” in which the physiological advantages of the two can be observed. After the creation of New China, rural women began to break away from the fate of “working at home in the kitchen” and actively devoted themselves to “socialist revolution and construction”, playing the role of “half the sky” in the entire rural production and life. With the socialization of production, social division of labor reduces the labor time and labor required for agricultural production, this leads to the engagement of left-behind women in heavy agricultural production, promotes the continuous transfer of surplus rural labor to non-agricultural industries, and also leads to a situation in which, “men going out to work, women staying in the countryside”.

Third, the continuous increase in labor and agricultural prices offsets the growth of the farmers’ income, which largely reduce the enthusiasm of farmers to cultivate land, and also makes their income stagnant. Consequently, the income gap between urban and rural residents has not been greatly improved (

Figure 6). To maximize family benefits, farmers prefer to work in cities rather than stay in rural areas. Furthermore, the dual household registration system in urban and rural areas requires that male elites, who meet the needs of individualization, have no family, and can bring the best benefits to the city should be screened out from the rural population. However, even if these eligible farmers move to the city, the urban social system still reflects their “peasant” status and excludes them from the welfare system. Therefore, in the attempt to “maximize family interests while avoiding risks as much as possible”, farmers tend to make a rational livelihood choice of “gender differentiation” and “family decentralization” migration.