Italian Consensus Statement on Patient Engagement in Chronic Care: Process and Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1)

- How to define patient engagement in chronic care?

- 2)

- How can patient engagement be measured?

- 3)

- What are the most recommended methodologies and tools to promote patient engagement?

- 4)

- What is the role of new technologies in promoting of patient engagement?

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Literature Review

2.3. Stakeholder Survey

2.4. Workshops with Experts

2.5. Finalization of the Consensus Statement

3. Results

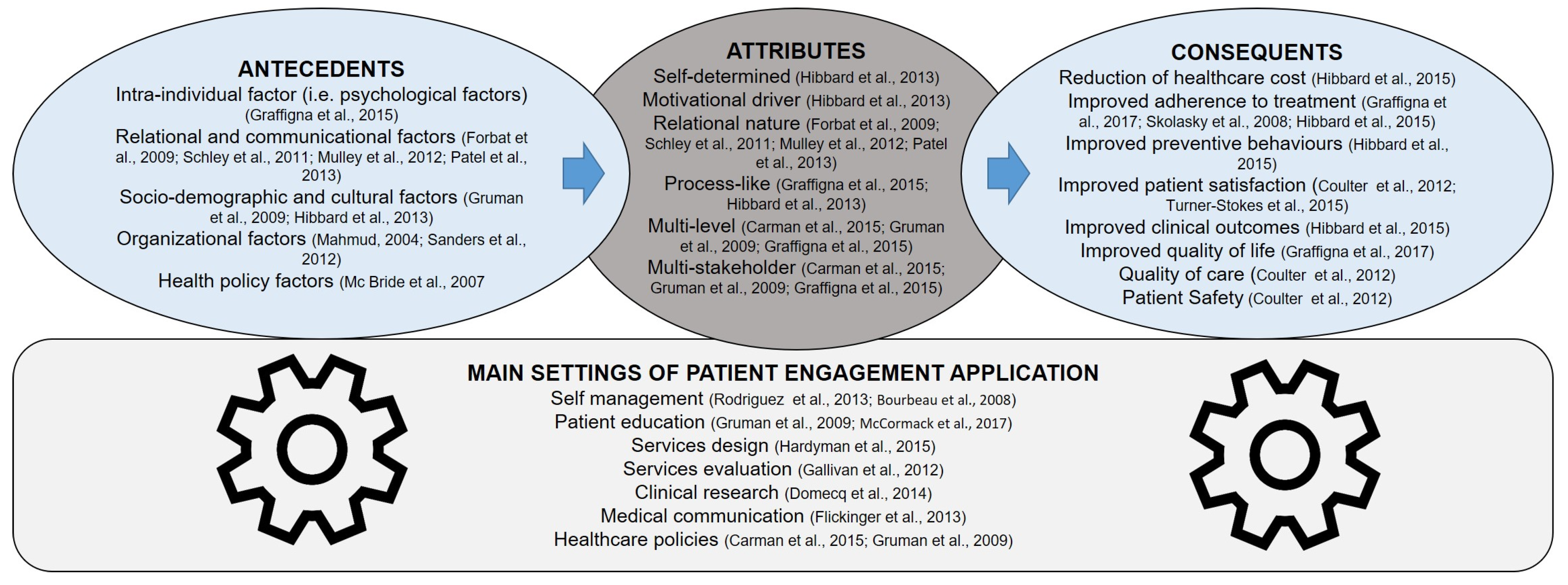

3.1. Query 1 – How Can Patient Engagement be Defined?

3.1.1. Main Evidence

3.1.2. Consensus Statement

3.2. Query 2 – How Can Patient Engagement be Measured?

3.2.1. Main Evidence

3.2.2. Consensus Statement

3.3. Query 3—What are the Best Practices to Promote Patient Engagement?

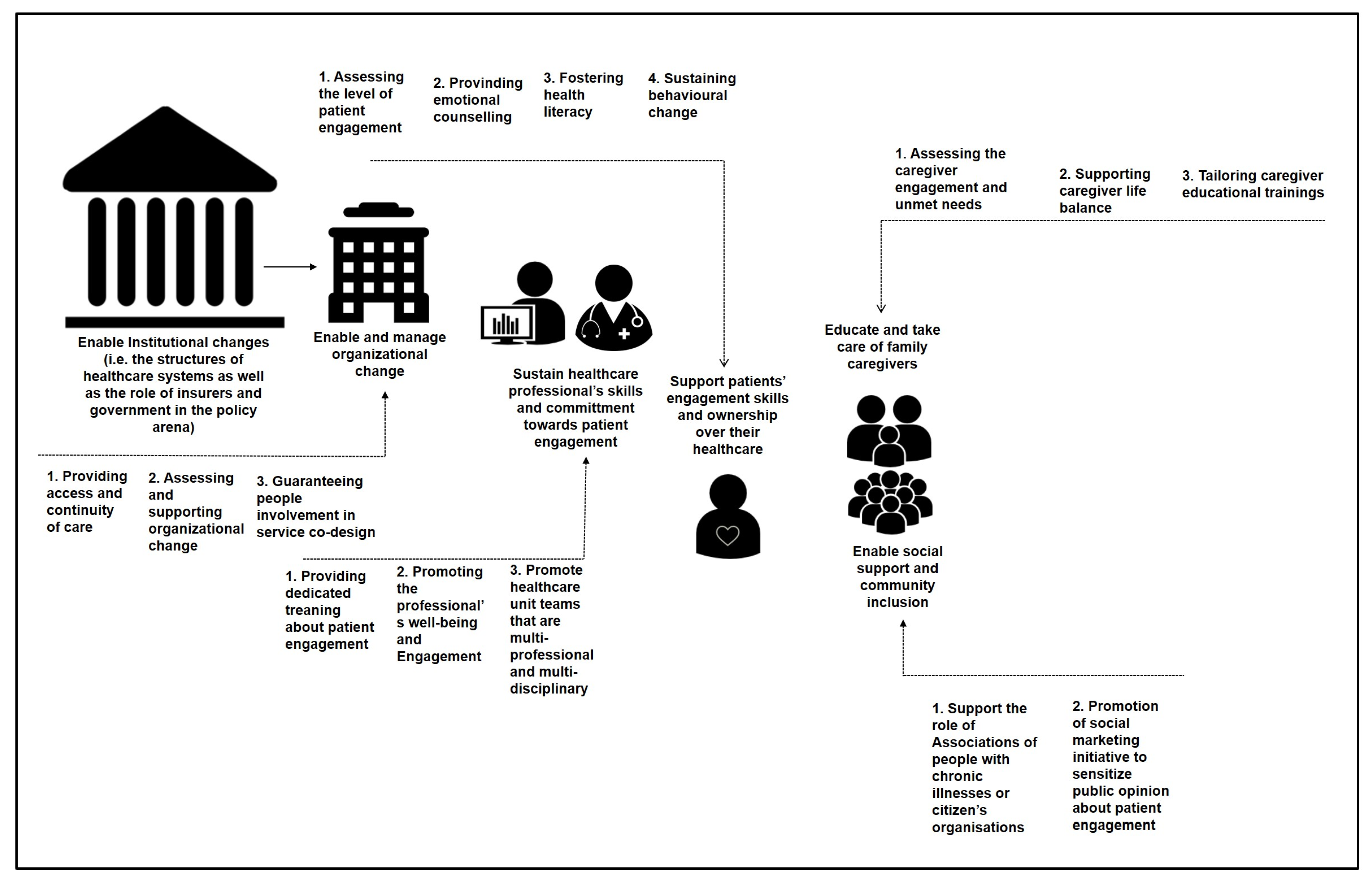

3.3.1. Main Evidence

3.3.2. Consensus Statements

3.3.3. More in Details

3.4. Query 4—What is the Role of the New Technologies in the Promotion of Patient Engagement?

3.4.1. Main Evidence

3.4.2. Consensus Statement

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Role | Responsibilities | Members |

|---|---|---|

| Organizing Committee | Was responsible for:

| G. Graffigna, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; A.C. Bosio, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; S. Barello, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; G. Castelnuovo, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; M. Corbo, Casa di Cura Privata del Policlinico, Milano; G. Riva, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano |

| Technical-Scientific Committee | Was composed of members with recognized experience and representativeness identified and invited by the Organizing Committee and was responsible for:

| E. Anessi Pessina, CERISMAS (Centro di ricerche e studi in management sanitario), Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; R. Bellantone, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Roma; R. Borgatti, IRCSS Istituto Eugenio Medea, Bosisio Parini, Lecco; A. Celano, APMAR (Associazione Persone con Malattie Reumatiche); A. Cicchetti, ALTEMS (Alta Scuola di Economia e Management dei Sistemi Sanitari), Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Roma; F. Consorti, SIPeM (Società Italiana di Pedagogia Medica); L. Coppola, DG Welfare Regione Lombardia; R. D’Elia, Ministero della Salute, Direzione Generale della Prevenzione; D. D’Ugo, SICO (Società Italiana Chirurgia Oncologica), Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Roma; F. De Lorenzo, European Cancer Patients Coalition, FAVO (Federazione Italiana Associazioni di Volontariato in Oncologia); F. Donatelli, Università degli Studi di Milano, Istituto Clinico Sant’Ambrogio Gruppo San Donato; A. Fauci, Istituto Superiore di Sanità; F. Giardina, CNOP (Consiglio Nazionale Ordine degli Psicologi); P. Iannone, Istituto Superiore di Sanità; D. Mannino, AMD (Associazione Medici Diabetologi); D. Mari, Fondazione IRCSS Ca’Grande - Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Università degli Studi di Milano; V. Mastrilli, Ministero della Salute, Direzione Generale della Prevenzione; P. Mocarelli, IRCCS Fondazione Don Gnocchi; E. Molinari, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano, Istituto Auxologico Italiano; F. Molteni, Villa Beretta - Presidio di Riabilitazione dell’Ospedale Valduce; A. Muratore, SICO (Società Italiana Chirurgia Oncologica); G. Muttillo, IPASVI (Infermieri Professionali, Assistenti Sanitari e Vigilatrici di Infanzia); G. Perseghin, SID (Società Italiana Diabetologia); G. Pintori, Inversa Onlus (associazione italiana per i pazienti affetti da idrosadenite suppurativa-acne inversa-); E. Previtali, AMICI Onlus (Associazione Nazionale per le Malattie Infiammatorie Croniche dell’Intestino); W. Ricciardi, Istituto Superiore di Sanità; E. Rizzato, Fondazione SPP (Scuola di Sanità Pubblica); E. Santoro, IRCCS - Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche “Mario Negri”; G. Spata, FNMCeO (Federazione Italiana Ordine dei Medici); M. Tessarollo, Residenze Anni Azzurri (Gruppo KOS); R. Valdagni, IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori. |

| Panel Jury | Had the authority to:

| A. Aglione, FAVO (Federazione Italiana Associazioni di Volontariato in Oncologia); G. Artioli, Arcispedale Santa Maria Nuova - IRCCS di Reggio Emilia; F. Avolio, Agenzia Regionale Sanitaria della Puglia; European Innovative Partnership for Active Healthy Ageing; C. Colombo, IRCSS Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri, Milano; S. Leone, A.M.I.C.I. Italia Onlus (Associazione Nazionale per le Malattie Infiammatorie Croniche dell’Intestino); M.C. Ghiotto, Regione del Veneto; B. Mazzoleni, Commissione Nazionale Ipasvi (Infermieri professionali, assistenti sanitari e vigilatrici di infanzia); R. Mete, Istituto Superiore di Studi Sanitari, Giuseppe Cannarella; P. Mosconi, IRCSS Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri, Milano; S. Nardi, Coordinamento nazionale delle Associazioni di Malati Cronici (CnAMC); C. Pinto, AIOM (Associazione Italiana Oncologia Medica); P. Quintaliani, SIN (Società Italiana Nefrologia), FIR (Fondazione Italiana Rene); G. Sanna, METIS FIMMG (Federazione italiana medici di medicina generale); S. Tonolo, ANMAR (Associazione Nazionale Malati Reumatici); A. Virzì, Società di Medicina Narrativa |

| President of the Jury | Had the authority to:

| G. Damiani, Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Roma |

| Writing Committee | Formed by members selected from the Jury, this Commitee reflects the competences and characteristics of the Panel’s multidisciplinarity, provided the newsroom with the final consensus document, following the modalities established and described in the Jury regulation. This document is an integration of the preliminary document that the Jury will produce in the hours following the Consensus Conference with a synthesis of the tasks that the Panel based itself on to formulate the recommendations. Moreover, the Writing Committee verified the coherence between the conclusions and the accompanying texts. | F. Avolio, Agenzia Regionale Sanitaria della Puglia; European Innovative Partnership for Active Healthy Ageing; G. Artioli, IPASVI Emilia Romagna (Infermieri professionali, assistenti sanitari e vigilatrici di infanzia), Università degli studi di Parma; S. Leone, A.M.I.C.I. Italia Onlus (Associazione Nazionale per le Malattie Infiammatorie Croniche dell’Intestino); P. Mosconi, IRCSS Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri, Milano |

| Scientific Secretariat | coordinated the collected and exchanged material and information between the different participants involved | G. Graffigna, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; S. Barello, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano |

| Organizational Secretariat | coordinated the operative organization of the conference | J. Menichetti, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; M. Savarese, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano |

| Members of the Expert Meetings | Held the role of assessing and synthesizing the evidence present in literature that were pertinent to the queries of the Consensus Conference. Particularly, they had the following jobs:

| Working Group on the definition of Patient Engagement: A. Bertoni, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; S. Donato, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; S. Gilardi, Università degli studi di Milano; C. Guglielmetti, Università degli studi di Milano; M. Lastretti, Ordine degli Psicologi del Lazio; L. Lombi, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; S. Ostuzzi, ALOMAR (Associazione Lombarda Malati Reumatici); G. Pitacco, ASUIT (Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Integrata di Trieste); M. Savarese, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; E. Vegni, Università degli Studi di Milano; N. Visalli, AMD (Associazione Medici Diabetologi) Working group on the measurement of patient engagement: S. Barello, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan; D. Bettega, Fatebenefratelli Ospedale Sacra Famiglia Erba (Como); F. Lucchi, Azienda Ospedaliera Spedali Civili Brescia; M. Magri, IPASVI Milano, Lodi, Monza e Brianza (Infermieri professionali, assistenti sanitari e vigilatrici di infanzia); M. Pozzi, Fatebenefratelli Ospedale Sacra Famiglia Erba (Como); L. Provenzi, IRCSS Istituto Eugenio Medea, Bosisio Parini, Lecco Working group on the promotion of patient engagement: M. Annoni, Fondazione Umberto Veronesi; M. P. Arnaboldi, IEO (Istituto Europeo Oncologico); L. Bellardita, IRCSS Istituto Nazionale Tumori; C. Carzaniga, GITIC (Gruppo Italiano Infermieri di Area Cardiovascolare); A. Castaldo IRCSS Istituto Piccolo Cottolengo Don Orione L. Garrino, SIPeM (Società Italiana di Pedagogia Medica); M. Gorli, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; M. Gulizia, ANMCO (Associazione Nazionale Medici Cardiologi Ospedalieri) A. Lotti, SIPeM (Società Italiana di Pedagogia Medica); J. Menichetti, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; M.L. Mottes, Diabete Forum; A.D.P.Mi Onlus (Associazione Diabetici della Provincia di Milano); N. Piana, Università degli Studi di Perugia; G. Quaglini, Parkinson Italia Onlus G. Scaratti, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; M. Tettamanti, GITIC (Gruppo Italiano Infermieri di Area Cardiovascolare); P. Varese, FAVO (Federazione Italiana Associazioni di Volontariato in Oncologia). Working group on the use of new technologies for patient engagement: S. Bigi, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; D. Bruttomesso, SID (Società Italiana di Diabetologia); L. Del Campo, FAVO (Federazione Italiana Associazioni di Volontariato in Oncologia); S. Franco, Istituto Superiore di Studi Sanitari, Giuseppe Cannarella; A. Mazzone, FADOI (Federazione delle Associazioni dei Medici Internisti Ospedalieri); G. Palumbo Villa Beretta - Presidio di Riabilitazione dell’Ospedale Valduce; D. Pero AIMAC (Associazione Italiana Malati di Cancro); G. Pintori, Inversa Onlus; G. Polvani, Università degli Studi di Milano, IRCSS Centro Cardiologico Monzino E. Santoro, IRCCS - Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche “Mario Negri”; S. Triberti, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano; A. Tzannis, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano |

Appendix B

| Title | Authors | Year | Characteristics of the Intervention | Type of Intervention | Use of Technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A smoking-cessation intervention for hospital patients | Stevens VJ, Glasgow RE, Hollis JF, et al. | 1993 | Multi-part inpatient intervention including counseling, videotapes, self-help materials and a phone call | Psychological support | yes |

| Patient empowerment and feedback did not decrease pain in seriously ill hospitalized adults | Desbiens NA, Wu AW, Yasui Y, Lynn J, Alzola C, Wenger NS, Connors AF Jr, Phillips RS, Fulkerson W. | 1998 | educational and empowerment nurse clinician-mediated intervention to relieve pain | Therapeutic education | no |

| Effects of preparatory videotapes on self-efficacy beliefs and recovery from coronary bypass surgery. | Mahler HI, Kulik JA. | 1998 | three types of videotapes | Psychological support | yes |

| A multicomponent intervention to prevent major bleeding complications in older patients receiving warfarin. A randomized, controlled trial | Beyth RJ, Quinn L, Landefeld CS | 2000 | multicomponent comprehensive program of warfarin management | Therapeutic education | no |

| The efficacy of playing a virtual reality game in modulating pain for children with acute burn injuries: a randomized controlled trial | Das DA, Grimmer KA, Sparnon AL, et al. | 2005 | virtual reality games | Therapeutic education | yes |

| Effect of education on blood pressure control in elderly persons a randomized controlled trial | Figar S, Galarza C, Petrlik E, Hornstein L, Rodríguez Loria G, Waisman G, Rada M, Soriano ER, de Quirós FG. | 2006 | self-management and patient empowerment workshops | Therapeutic education | no |

| A telephone-delivered empowerment intervention with patients diagnosed with heart failure | Shearer NB, Cisar N, Greenberg EA. | 2007 | telephone-delivered empowerment intervention to facilitate purposeful participation in goal attainment, self-management of disease, and perception of functional health | Psychological support | yes |

| Changes in diabetes distress related to participation in an internet based diabetes care management program and glycemic control | Fonda SJ, McMahon GT, Gomes HE, Hickson S, Conlin PR. | 2009 | Internet-based care management program | Therapeutic education | yes |

| Community based peer led diabetes self management. A randomized trial | Lorig, Kate, Ritter, Philip L., Villa, Frank J., Armas, Jean | 2009 | community-based, peer-led diabetes self-management program | Psychological support | no |

| Making the most of your healthcare intervention for older adults with multiple chronic illnesses | Hochhalter, Angela K. et al. | 2010 | patient engagement intervention for older adults with multiple chronic illnesses called Making the Most of Your Healthcare | Therapeutic education | no |

| Randomized control trial of the health empowerment intervention: feasibility and impact | Crawford Shearer NB, Fleury JD, Belyea M. | 2010 | Health Empowerment Intervention to promote the use of personal resources and social contextual resources | Psychological support | no |

| Multimedia education programme for patients with a stoma Effectiveness evaluation | Lo, Shu-Fen | 2011 | multimedia education programme | Therapeutic education | yes |

| Cluster-randomized trial of a mobile phone personalized behavioral intervention for blood glucose control | Quinn C. C., Shardell M. D., Terrin M. L., Barr E. A., Ballew S. H., Gruber-Baldini A. L. | 2011 | patient/provider web portals | Therapeutic education | yes |

| Efficacy of ongoing group-based diabetes self-management education for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus A randomised controlled trial | Rygg, Lisbeth et al. | 2012 | diabetes self-management education | Therapeutic education | no |

| Enhanced medical rehabilitation increases therapy intensity and engagement and improves functional outcomes in postacute rehabilitation of older adults a randomized controlled trial | Lenze EJ, Host HH, Hildebrand MW, Morrow-Howell N, Carpenter B, Freedland KE, Baum CA, Dixon D, Doré P, Wendleton L, Binder EF. | 2012 | Enhanced Medical Rehabilitation | Therapeutic education | no |

| Effectiveness of peer-led self-management coaching for patients recently diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care: a randomized controlled trial | Van der Wulp I, de Leeuw JR, Gorter KJ, Rutten GE. | 2012 | peer led self-management coaching programme | Psychological support | no |

| Effects of a Web-based intervention for adults with chronic conditions on patient activation: online randomized controlled trial | Solomon M., Wagner S. L., Goes J | 2012 | MyHealth Online, a patient portal featuring interactive health applications accessible via the Internet | Therapeutic education | yes |

| Effect of patient activation on self management in patients with heart failure | Shively, Martha J., Larson, Carolyn B. | 2013 | tailored face-to-face or telephonic program focused on having individualized self-selected health goals | Therapeutic education | yes |

| Effectiveness of a quality improvement intervention targeting cardiovascular risk factors: are patients responsive to information and encouragement by mail or post? | Senesael E, Borgermans L, Van De Vijver E, Devroey D. | 2013 | information and regular encouragement by email or letter on cardiovascular risk factors | Support to medical communication | no |

| Effectiveness of general practice based, practice nurse led telephone coaching on glycaemic control of type 2 diabetes the Patient Engagement and Coaching for Health PEACH pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial | Blackberry ID, Furler JS, Best JD, Chondros P, Vale M, Walker C, Dunning T, Segal L, Dunbar J, Audehm R, Liew D, Young D. | 2013 | practice nurse led structured telephone coaching program | Therapeutic education | yes |

| Effects of a web-based patient activation intervention to overcome clinical inertia on blood pressure control cluster randomized controlled trial | Thiboutot J, Sciamanna CN, Falkner B, Kephart DK, Stuckey HL, Adelman AM, Curry WJ, Lehman EB. | 2013 | Web-Based Patient Activation Intervention with tailored messages suggesting questions to ask to improve blood pressure control | Support to medical communication | yes |

| Impact of single session motivational interviewing on clinical outcomes following periodontal maintenance therapy | Brand VS, Bray KK, MacNeill S, Catley D, Williams K. | 2013 | motivational interviewing | Therapeutic education | no |

| Internet based dyspnea self-management support for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Nguyen HQ, Donesky D, Reinke LF, Wolpin S, Chyall L, Benditt JO, Paul SM, Carrieri-Kohlman V. | 2013 | Internet-based and face-to-face dyspnea selfmanagement programs | Therapeutic education | yes |

| The role of patient activation in improving blood pressure outcomes in Black patients receiving home care | Ryvicker, Miriam | 2013 | phone-based educational intervention for blood pressure skills building | Therapeutic education | yes |

| Online disease management of diabetes: engaging and motivating patients online with enhanced resources-diabetes (EMPOWER-D), a randomized controlled trial | Tang P. C., Overhage J. M., Chan A. S., Brown N. L., Aghighi B., Entwistle M. P., et al. | 2013 | (1) wirelessly uploaded home glucometer readings with graphical feedback; (2) comprehensive patient-specific diabetes summary status report; (3) nutrition and exercise logs; (4) insulin record; (5) online messaging with the patient’s health team; (6) nurse care manager and dietitian providing advice and medication management; and (7) personalized text and video educational ‘nuggets’ dispensed electronically by the care team | Therapeutic education | yes |

| Effect of a participant driven health education programme in primary care for people with hyperglycaemia detected by screening 3year results from the Ready to Act randomized controlled trial nested within the ADDITION Denmark study | Maindal HT, Carlsen AH, Lauritzen T, Sandbaek A, Simmons RK. | 2014 | Ready to Act programme with 2 individual counselling interviews and 8 group sessions for motivation, informed decision-making, action experience, social involvement | Therapeutic education | no |

| Effects of a patient oriented decision aid for prioritising treatment goals in diabetes Pragmatic randomised controlled trial | Denig, Petra et al. | 2014 | patient oriented decision aid | Support to medical communication | no |

| Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education the EMPOWER cluster randomized trial | Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A, Ahmed S. | 2014 | deprescribing patient empowerment intervention on benzodiazepine use and a stepwise tapering protocol | Therapeutic education | no |

| A salutogenic program to enhance sense of coherence and quality of life for older people in the community A feasibility randomized controlled trial and process evaluation | Tan, Khoon Kiat, Chan, Sally Wai-Chi, Wang, Wenru, Vehviläinen-Julkunen, Katri | 2015 | Resource Enhancement and Activation Program to develop the well-being and QoL of older people by strengthening their SOC, activation, and resilience through 24 activities | Psychological support | no |

| Effectiveness of motivational interviewing to improve therapeutic adherence in patients over 65 years old with chronic diseases A cluster randomized clinical trial in primary care | Moral RR, Torres LA, Ortega LP, Larumbe MC, Villalobos AR, García JA, Rejano JM; Collaborative Group ATEM-AP Study. | 2015 | motivational interviewing | Therapeutic education | no |

| Encounter Decision Aid vs Clinical Decision Support or Usual Care to Support Patient Centered Treatment Decisions in Osteoporosis The Osteoporosis Choice Randomized Trial II | LeBlanc A, Wang AT, Wyatt K, Branda ME, Shah ND, Van Houten H, Pencille L, Wermers R, Montori VM. | 2015 | encounter decision aid | Support to medical communication | no |

| Feasibility of Standardized Clinician Methodology for Patient Training on Hospital to Home Transitions | Wehbe-Janek H, Hochhalter AK, Castilla T, Jo C. | 2015 | standardized clinician methodology intervention | Therapeutic education | no |

| Patient Empowerment Improved Perioperative Quality of Care in Cancer Patients Aged ≥ 65 Years A Randomized Controlled Trial | Schmidt M, Eckardt R, Scholtz K, Neuner B, von Dossow-Hanfstingl V, Sehouli J, Stief CG, Wernecke KD, Spies CD; PERATECS Group. | 2015 | Patient empowerment intervention with information booklet and patient diary | Therapeutic education | no |

| Peer Coaches to Improve Diabetes Outcomes in Rural Alabama A Cluster Randomized Trial | Safford MM, Andreae S, Cherrington AL, Martin MY, Halanych J, Lewis M, Patel A, Johnson E, Clark D, Gamboa C, Richman JS. | 2015 | peer-coaching intervention | Psychological support | no |

| Safe and effective use of medicines for patients with type 2 diabetes A randomized controlled trial of two interventions delivered by local pharmacies | Kjeldsen LJ, Bjerrum L, Dam P, Larsen BO, Rossing C, Søndergaard B, Herborg H. | 2015 | individually targeted self-management intervention (1. brief, 2. extended) | Therapeutic education | no |

| Activating Patients With a Tailored Bone Density Test Results Letter and Educational Brochure: the PAADRN Randomized Controlled Trial. | Wolinsky FD, Lou Y, Edmonds SW, Hall SF, Jones MP, Wright NC, Saag KG, Cram P, Roblin DW; PAADRN Investigators.. | 2016 | tailored patient activation letter communicating test results plus educational brochure | Therapeutic education | no |

| Assessing the effect of culturally specific audiovisual educational interventions on attaining self-management skills for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Mandarin- and Cantonese-speaking patients: a randomized controlled trial. | Poureslami I, Kwan S, Lam S, Khan NA, FitzGerald JM. | 2016 | culturally and linguistically specific audiovisual educational materials for COPD self-management | Therapeutic education | no |

| Cardiac rehabilitation using the Family-Centered Empowerment Model versus home-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with myocardial infarction a randomised controlled trial | Vahedian-Azimi A, et al. | 2016 | hybrid cardiac rehabilitation programme with educational group sessions involving family members | Therapeutic education | no |

| Do empowered stroke patients perform better at self-management and functional recovery after a stroke? A randomized controlled trial. | Sit JW, Chair SY, Choi KC, Chan CW, Lee DT, Chan AW, Cheung JL, Tang SW, Chan PS, Taylor-Piliae RE. | 2016 | Health Empowerment Intervention for Stroke Self-management | Psychological support | no |

| Does a decision aid for prostate cancer affect different aspects of decisional regret, assessed with new regret scales? A randomized, controlled trial | van Tol-Geerdink, Julia J., Jan Willem H. | 2016 | Decision aid for radical PCa treatments | Support to medical communication | no |

| Effects of a home-based activation intervention on self-management adherence and readmission in rural heart failure patients: the PATCH randomized controlled trial. | Young L, Hertzog M, Barnason S. | 2016 | telephone-based patient activation care at home intervention | Therapeutic education | yes |

| Encouraging early discussion of life expectancy and end-of-life care: A randomised controlled trial of a nurse-led communication support program for patients and caregivers. | Walczak A, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, Davidson PM, Young J, Epstein RM, Costa DS, Clayton JM. | 2016 | nurse-led Communication Support Program for support end-of-life care | Support to medical communication | no |

| Increasing patient involvement in the diabetic foot pathway a pilot randomized controlled trial | McBride E, Hacking B, O’Carroll R, Young M, Jahr J, Borthwick C, Callander A, Berrada Z. | 2016 | Decision Navigation: a multicomponent intervention developed to promote informed treatment decision-making | Support to medical communication | no |

| Patient and Partner Feedback Reports to Improve Statin Medication Adherence: A Randomized Control Trial. | Reddy A, Huseman TL, Canamucio A, Marcus SC, Asch DA, Volpp K, Long JA. | 2016 | 1) daily alarm and a weekly medication adherence feedback report; 2) plus sharing of alarm/report with a friend, family member, or a peer | Therapeutic education | yes |

| The effect of a patient centred care bundle intervention on pressure ulcer incidence (INTACT): A cluster randomised trial. | Chaboyer W, Bucknall T, Webster J, McInnes E, Gillespie BM, Banks M, Whitty JA, Thalib L, Roberts S, Tallott M, Cullum N, Wallis M. | 2016 | patient centred care bundle educational intervention ulcer incidence | Therapeutic education | no |

| The impact of sharing personalised clinical information with people with type 2 diabetes prior to their consultation A pilot randomised controlled trial | O’Donnell, M. et al. | 2016 | booklet including personalised clinical information | Support to medical communication | no |

| Effectiveness of personalised support for self management in primary care a cluster randomised controlled trial | Eikelenboom N, van Lieshout J, Jacobs A, Verhulst F, Lacroix J, van Halteren A, Klomp M, Smeele I, Wensing M. | 2016 | Patient feedback scale and personalized self-management support | Psychological support | no |

References

- Couto, J.E.; Comer, D.M. Patient engagement: The critical catalyst to health reform in the USA. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2012, 1, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clancy, C.M. Patient engagement in health care. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 46, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, A. Patient engagement—What works? J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2012, 35, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruman, J.; Rovner, M.H.; French, M.E.; Jeffress, D.; Sofaer, S.; Shaller, D.; Prager, D.J. From patient education to patient engagement: Implications for the field of patient education. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 78, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barello, S.; Triberti, S.; Graffigna, G.; Libreri, C.; Serino, S.; Hibbard, J.; Riva, G. eHealth for patient engagement: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2016, 6, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Greene, J.; Shi, Y.; Mittler, J.; Scanlon, D. Taking the long view: How well do patient activation scores predict outcomes four years later? Med. Care Res. Rev. 2015, 72, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graffigna, G.; Barello, S.; Bonanomi, A.; Riva, G. Factors affecting patients’ online health information-seeking behaviours: The role of the Patient Health Engagement (PHE) Model. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, A. Leadership for Patient Engagement; King’s Fund: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hochhalter, A.K.; Song, J.; Rush, J.; Sklar, L.; Stevens, A. Making the Most of Your Healthcare intervention for older adults with multiple chronic illnesses. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 81, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.; Hibbard, J.H.; Sacks, R.; Overton, V.; Parrotta, C.D. When patient activation levels change, health outcomes and costs change, too. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, P.J.; Dias, J.; Howard, S.; Kintziger, K.W.; Hudson, M.F.; Seol, Y.H.; Sodomka, P. Personal health records and hypertension control: A randomized trial. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2012, 19, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocloo, J.; Matthews, R. From tokenism to empowerment: Progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2016, 25, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graffigna, G. Promoting Patient Engagement and Participation for Effective Healthcare Reform; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, E.M.; Van Regenmortel, T.; Vanhaecht, K.; Sermeus, W.; Van Hecke, A. Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: A concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 1923–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwyn, G.; Crowe, S.; Fenton, M.; Firkins, L.; Versnel, J.; Walker, S.; Cook, I.; Holgate, S.; Higgins, B.; Gelder, C. Identifying and prioritizing uncertainties: Patient and clinician engagement in the identification of research questions. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2010, 16, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barello, S.; Graffigna, G.; Vegni, E.; Savarese, M.; Lombardi, F.; Bosio, A.C. “Engage me in taking care of my heart”: A grounded theory study on patient-cardiologist relationship in the hospital management of heart failure. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e005582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T. Patient and public involvement in chronic illness: Beyond the expert patient. BMJ 2009, 49, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, N.J.; Ward, K.J.; O’Rourke, A.J. The “expert patient”: Empowerment or medical dominance? The case of weight loss, pharmaceutical drugs and the Internet. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.; Baker, M. “Expert patient”—Dream or nightmare? BMJ 2004, 328, 723–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, S.; Winterbottom, A.; Cross, P.; Redding, D. The Quality of Patient Engagement and Involvement in Primary Care; King’s Fund: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hardyman, W.; Daunt, K.L.; Kitchener, M. Value Co-Creation through Patient Engagement in Health Care: A micro-level approach and research agenda. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, A.R. The Patient Engagement Imperative. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.J.; Gibson, B.; Robinson, P.G. Is quality of life determined by expectations or experience? BMJ 2001, 322, 1240–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, A.; Britten, N.; Lynch, J. Theoretical directions for an emancipatory concept of patient and public involvement. Health 2012, 16, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoemaker, S.J.; de Ramalho Oliveira, D.; Alves, M.; Ekstrand, M. The medication experience: Preliminary evidence of its value for patient education and counseling on chronic medications. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 83, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontaine, P.; Whitebird, R.; Solberg, L.; Tillema, J.; Smithson, A.; Crabtree, B.F. Minnesota’s Early Experience with Medical Home Implementation: Viewpoints from the Front Lines. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 30, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathert, C.; Brandt, J.; Williams, E.S. Putting the “patient” in patient safety: A qualitative study of consumer experiences. Health Expect. 2012, 15, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Greene, J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: Better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manary, M.P.; Boulding, W.; Staelin, R.; Glickman, S.W. The Patient Experience and Health Outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barello, S.; Graffigna, G. Engagement-sensitive decision making: Training doctors to sustain patient engagement in medical consultations. In Patient Engagement: A Consumer-Centered Model to Innovate Healthcare; DeGruyter Open: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; pp. 78–93. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, N.; Fleming, C. Consumer and Provider Perspectives on Shared Decision Making: A Systematic Review of the Peer-Reviewed Literature; Mathematica Policy Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Légaré, F. Shared decision making: Moving from theorization to applied research and hopefully to clinical practice. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 91, 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoul, G.; Clayman, M.L. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ. Couns. 2006, 60, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwyn, G.; Lloyd, A.; May, C.; van der Weijden, T.; Stiggelbout, A.; Edwards, A.; Frosch, D.L.; Rapley, T.; Barr, P.; Walsh, T.; et al. Collaborative deliberation: A model for patient care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 97, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, S.W.; Faber, M.J.; Durand, M.A.; Thompson, R.; Elwyn, G. A classification model of patient engagement methods and assessment of their feasibility in real-world settings. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 95, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwyn, G.; Frosch, M.L.; Thomson, R.; Joseph-Williams, N.; Lloyd, A.; Kinnersley, P.; Cording, E.; Tomson, D.; Dodd, C.; Rollnick, S.; et al. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haase, J.E.; Britt, T.; Coward, D.D.; Leidy, N.K.; Penn, P.E. Simultaneous Concept Analysis of Spiritual Perspective, Hope, Acceptance and Self-transcendence. Image J. Nurs. Sch. 1992, 24, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.O.; Avant, K.C. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 1–230. [Google Scholar]

- Graffigna, G.; Barello, S.; Riva, G.; Castelnuovo, G.; Corbo, M.; Coppola, L.; Daverio, G.; Fauci, A.; Iannone, P.; Ricciardi, W.; et al. Recommandation for patient engagement promotion in care and cure for chronic conditions. Recenti Prog. Med. 2017, 108, 455–475. [Google Scholar]

- Menichettij, C.; Bussolind, G.; Barello, S.; Graffigna, G.; Corbo, M.; Coppola, L.; Daverio, G.; Fauci, A.; Iannone, P.; Ricciardi, W.; et al. Engaging older people in healthy and active lifestyles: A systematic review. Ageing Soc. 2016, 36, 2036–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichetti, J.; Graffigna, G. How older citizens engage in their health promotion: A qualitative research-driven taxonomy of experiences and meanings. BMJ Open 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichetti, J.; Graffigna, G.; Steinsbekk, A. What are the contents of patient engagement interventions for older adults? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Stockard, J.; Mahoney, E.R.; Tusler, M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and Measuring Activation in Patients and Consumers. Health Serv. Res 2004, 39, 1005–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carman, K.L.; Dardess, P.; Maurer, M.; Sofaer, S.; Adams, K.; Bechtel, C.; Sweeney, J. Patient and family engagement: A framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbat, L.; Cayless, S.; Knighting, K.; Cornwell, J.; Kearney, N. Engaging patients in health care: An empirical study of the role of engagement on attitudes and action. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 74, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graffigna, G.; Barello, S.; Bonanomi, A. The role of Patient Health Engagement model (PHE-model) in affecting patient activation and medication adherence: A structural equation model. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunston, R.; Lee, A.; Boud, D.; Brodie, P.; Chiarella, M. Co-Production and Health System Reform—From Re-Imagining to Re-Making. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2009, 68, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, T.; Korczak, V. Community consultation and engagement in health care reform. Aust. Health Rev. 2007, 1, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Duke, C.C.; Lynch, W.D.; Smith, B.; Winstanley, J. Validity of a New Patient Engagement Measure: The Altarum Consumer Engagement (ACE) MeasureTM. Patient 2015, 8, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graffigna, G.; Barello, S.; Bonanomi, A.; Lozza, E. Measuring patient engagement: Development and psychometric properties of the patient health engagement (PHE) scale. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battersby, M.W.; Ask, A.; Reece, M.M.; Markwick, M.J.; Collins, J.P. The Partners in Health scale: The development and psychometric properties of a generic assessment scale for chronic condition self-management. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2003, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howie, J.G.R.; Heaney, D.J.; Maxwell, M.; Walker, J.J. A comparison of a Patient Enablement Instrument (PEI) against two established satisfaction scales as an outcome measure of primary care consultations. Fam. Pract. 1998, 15, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramm, J.M.; Strating, M.M.H.; de Vreede, P.L.; Steverink, N.; Nieboer, A.P. Validation of the self-management ability scale (SMAS) and development and validation of a shorter scale (SMAS-S) among older patients shortly after hospitalisation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.; Chastain, R.L.; Ung, E.; Shoor, S.; Holman, H.R. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989, 32, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortte, K.B.; Falk, L.D.; Castillo, R.C.; Johnson-Greene, D.; Wegener, S.T. The Hopkins Rehabilitation Engagement Rating Scale: Development and Psychometric Properties. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007, 88, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwicker, D. Preparedness for caregiving scale. Mov. Disord. 2010, 56, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- DeCamp, L.R.; Leifheit, K.; Shah, H.; Valenzuela-Araujo, D.; Sloand, E.; Polk, S.; Cheng, T.L. Cross-cultural validation of the parent-patient activation measure in low income Spanish- and English-speaking parents. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 2055–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Collins, P.A.; Mahoney, E.; Baker, L.H. The development and testing of a measure assessing clinician beliefs about patient self-management. Health Expect. 2010, 13, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.; Sacks, R.M.; Hibbard, J.H.; Overton, V. How much do clinicians support patient self-management? The development of a measure to assess clinician self-management support. Healthcare 2016, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linden, A.; Butterworth, S.W.; Prochaska, J.O. Motivational interviewing-based health coaching as a chronic care intervention. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2010, 16, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, E.; Cornwell, P.; Fleming, J.; Haines, T. Patient centered goal-setting in a subacute rehabilitation setting. Disabil. Rehabil. 2010, 32, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigi, S. Communication skills for patient engagement: Argumentation competencies as means to prevent or limit reactance arousal, with an example from the Italian healthcare system. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, T.; Frankel, R.M.; Krupat, E. Enhancing clinician communication skills in a large healthcare organization: A longitudinal case study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005, 58, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deen, D.; Lu, W.H.; Rothstein, D.; Santana, L.; Gold, M.R. Asking questions: The effect of a brief intervention in community health centers on patient activation. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 84, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knops, A.M.; Legemate, D.A.; Goossens, A.; Bossuyt, P.M.M.; Ubbink, D.T. Decision aids for patients facing a surgical treatment decision: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. 2013, 257, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromer, L. Implementing chronic care for COPD: Planned visits, care coordination, and patient empowerment for improved outcomes. Int. J. COPD 2011, 6, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Analysis of the Scientific Evidence Related to Queries 1 and 2 | |

|---|---|

| Method and Search Strategy | For queries 1 and 2 the literature analysis followed the principles of conceptual analysis, widely spread in social science research [8,37,38]. Cochrane Library, Isi Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, PsychInfo were subject to a systematic search according to the following keywords search string: [“patient engag*” OR “consumer engag*” OR “client engag*” OR “citizen engag*”] AND [“definition” OR “conceptualization” OR measure OR “questionnaire”]. No restriction was applied regarding the year, the language or the document type. Additional key references were added and analyzed on the basis of their inclusion in the bibliographical references lists of the studies initially selected for the analysis. |

| Selection Process | In the analysis, only the manuscripts that reported a conceptual definition or a modelling theory of the concept of patient engagement were included. The manuscripts were considered as “conceptual” if they discussed in depth the theoretical underpinning of a construct and its determinants and characteristics. Furthermore, careful attention was given to the modality of operationalization and measurement of the theoretical constructs proposed in the analyzed studies. First, the duplicates generated from the systematic search were delated. At a later stage, all the titles and abstracts found were read and analyzed with the aim of excluding irrelevant and incoherent sources with the study inclusion criteria. Finally, the full texts were read and thoroughly analyzed to understand how they conceptualized, described and operationalized the concept of patient engagement. The process of analysis of the sources was ongoing until no more meaning references were retrieved. |

| Analysis of the Scientific Evidence Related to Queries 3 and 4: | |

| Method and Search Strategy | With the aim of answering queries 3 and 4, Cochrane Library, ISI Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, PsychInfo were the object of a systematic research conducted with the following search string: (“patient* engag*”) AND [“plan*” OR “practice*” OR “intervention*” OR “program*” OR “protocol*” OR “trial*”]. No restriction was applied regarding the year, the language or the type of document. The search was integrated on the basis of an accurate analysis of the bibliographical references reported in the studies found. |

| Selection Process | We adopted the following inclusion criteria: (1) Years covered by the research: all the literature produced until the year 2016; (2) Population: studies that explicitly discussed the concept of Patient Engagement in the context of chronic illnesses; (3) Types of studies: with the aim of focusing the analysis on the most significant scientific evidence, only studies with Randomized Controlled Trial were included. Although we are aware that due to the infancy of the scientific debate about patient engagement the number of RCT on programs aimed at promoting patient engagement might be in a limited number, we preferred to keep this restrictive criterion in order to assess the maximum level of evidence achieved in the scientific literature about patient engagement initiatives. The limitedness of this decision has been however complemented by the following steps of the process: i.e., the experts survey and the workshops. The identified studies underwent another selection through the analysis of the titles and abstracts, to which followed an exclusion of those that were clearly unsuitable for the queries and inclusion criteria previously described. Of all the selected abstracts the full texts were then obtained and divided per topic area (in reference to the CC queries) and types of study. The systematic search of the sources was purposefully initially broad, in order to include all of the potentially relevant studies for the study objectives. The articles found were then further selected in a second phase of screening. Specifically, during an initial selection phase all the sources found were analyzed with regard to their title and abstract. This analysis allowed for the selection of only the relevant studies according to the following criteria: (1) being a Randomized Controlled Trial; (2) referring to chronic patients; (3) presenting measurement data of the impact of the intervention finalized to increase Patient Engagement; (4) being a peer-reviewed article with full text availability. |

| Supplementary Materials (Tables S1 and S2)Related to the Two Reviews Outcomes | |

| Main Outcome | The results achieved by these two literature review were deeply commented and reported in two reports provided to the experts participating in the workshops and experts’ panel. Original reports are partially published [39]. The systematic literature review was partially published in this manuscript [40] |

| Discipline | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Medicine and biology | 35 | 34 |

| Psychology | 24 | 23 |

| Sociology | 3 | 3 |

| Nursing | 15 | 14 |

| Patient advocacy | 11 | 10 |

| Policy making | 8 | 8 |

| Public health | 4 | 4 |

| Health economics | 3 | 3 |

| Health engineering | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 104 | 100% |

| Author(s), Year [Reference] | Definition of “Engagement” | Setting of Application | Level of Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mahmud, 2004 | It is a process of healthcare priorities definition. It consists in empowering people to provide input to decisions that affect their lives and encourages support for those decisions, which in turn improves the public’s trust and confidence in the healthcare system. | Health service design | Macro (organizational factors) |

| Dearing et al., 2005 | Developing “engagement” means fostering those client-therapist working alliances that help the client to gain a more realistic understanding of the nature, process, and expected outcomes of treatment. | Healthcare communication/relationship | Micro level (relational factors) |

| Davis et al., 2007 | Option for patients to be informed partners in their care, including a recasting of the care relationship where the clinician enacts the role of adviser, and patients or designated surrogates for incapacitated patients serve as the locus of decision making. | Healthcare communication/relationship | Micro level (relational factors) |

| Mc Bride et al., 2007 | It is a process that allows, at different levels, the wider community to have a say in the future direction of people’s health care. | Health policy design | Macro level (health policy factors) |

| Dunston et al., 2009 | Dialogic and co-productive partnership among the healthcare system, healthcare professionals and citizen/healthcare consumers whereby these actors become co-productive. | Health service design | Meso level (organizational factors) |

| Forbat et al., 2009 | [to engage patients means] working in partnership with service-users, keeping them informed about: (i) service redesign/improvement processes, (ii) policy, (iii) research and (iv) their own care/treatment. It also implies balancing powers between patients and health providers. | Health service design | Meso level (organizational factors) |

| Schley et al., 2011 | Engaging clients in the therapeutic encounter means developing collaboration, perceived usefulness, and positive client/therapist interaction. | Healthcare communication/relationship | Micro level (relational factor) |

| Mulley et al., 2012 | A process of shared decision making, described as a sequence of three types of conversation - team talk, option talk and decision talk. [engaging patients] - means creating a preference diagnosis which has a unique profile of risks, benefits and side effects. | Healthcare communication | Micro level (relational factors) |

| Sanders et al., 2012 | A collaborative, bidirectional process whereby patients’ knowledge and experience is shared in a dialogue with program developers, health practitioners and researchers. It involves actively harnessing the consumer’s voice to strengthen the quality, relevance and effectiveness of an intervention. | Healthcare design | Meso level (organizational factors) |

| Carman et al., 2013 | Patients, families, their representatives, and health professionals working in active partnership at various levels across the health care system—direct care, organizational design and governance, and policy making—to improve health and health care. | Healthcare deign | Macro level (policy factors) |

| Patel et al., 2013 | The [engaged] patients have the ability to balance clinical information and professional advice with their own needs and preferences. It is a collaborative approach where shared decision making, equal distribution of power and exchange of clinical information are enacted. | Healthcare communication | Micro level (relational factors) |

| Scale Name | Characteristics | Pros | Cons | Recommended Use to |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Engagement Assessment Scales | ||||

| Altarum Consumer Engagement (ACE) [49] | 15 item scale that assesses the individual’s behavior in managing his/her health and his/her decision-making regarding heath care. The instrument consists of four sub-scales (commitment, informed choice, navigation, ownership) each indicative of a specific aspect of Engagement. | The scale is very detailed and allows for good assessment of the patient’s self-management skill. | The scale is quite long and complicated in its clinical application. The scale does not measure the emotional-motivational component of Engagement. | Assess cognitive and behavioural attitudes of patients in self-management |

| Patient Activation Measure(PAM) [43] | Scale formed of 13 items that assess the person’s current behavioural abilities in managing the illness and the treatment prescriptions. | The scale is broadly used and has validation in several languages | It focuses on the behavioural and cognitive components of Engagement, and does not analyze the emotional-motivational component of Engagement | Assess cognitive and behavioural attitudes of patients in self-management |

| Patient Health Engagement Scale (PHE-s) [50] | 5 item scale developed on the basis of a solid conceptual evidence-based model of the patient with chronic illness’ experience of Engagement (PHE-model). The scale assesses the ability to reconfigure ones’ identity from passive receiver to co-author of the heath service. | The scale is easy and fast to use in the clinical context. The scale is very reliable in measuring the psychological attitude of patients towards Engagement | The scale does not measure behavioural components of the patient’s self-management. | Assess emotional and motivation readiness of patients to engage in the healthcare journey |

| The Partners in Health (PHI) Scale [51] | Developed by Battersby and colleagues (2003), the PIH is a generic assessment scale for patients managing their chronic medical conditions. The scale consists of 11 items aimed at measuring the patients’ features regarding the following dimensions: (1) Knowledge of the condition and various treatment options; (2) Ability to negotiate a plan of care; (3) Engagement in activities that protect and promote health; (4) Monitoring and management of the symptoms and signs of the clinical condition(s). Both patients and health professionals judged the scale as acceptable and easy to use, and the health professionals endorsed its clinical utility | The scale enables a multidimensional analysis of engagement in the various domains of patients’ experience. It also allows to mirror patients’ and healthcare providers’ evaluations of engagement | The scale cannot be used to measure the emotional and motivational components of the engagement experience. The scale is quite long and complex to used | The scale is usable for an initial and very comprehensive assessment of engagement, but it is less usable in reiterative assessment due to the time of completion |

| The Patient Enablement Instrument (PEI) [52] | The Patient Enablement Instrument (PEI) – developed by Howie and colleagues (1998) is designed to measure the patients’ ability to understand the nature of their problems and cope with their illness. This tool addresses six questions regarding a patient’s recent consultations, and, assess the following areas: how much they felt able to (1) cope with life, (2) understand their illness, (3) cope with their illness, (4) keep healthy, (5) feel confident about their health, and (6) able to help themselves. Scores were categorized to indicate low (0–4), medium (score 5–9), and high enablement (10–12) | The scale has been widely used and found to be reliable (Cronbach’s α = 0.897). | The scale is mainly related to patients’ ability to understand the nature of their problem and the way to cope with it and it is only related to the consultation experience | The PEI was developed to be used in primary care and is to be completed by the patient after consultation. |

| The Self-Management Ability Scale (SMAS) [53] | Developed by Cramm and colleagues (2012) and based on the self-management of well-being (SMW) theory (Steverink et al., 2005), the 30-item Self-Management Ability Scale (SMAS) measures self-management abilities (SMA). The 30-item SMAS consists of six five-item subscales. Each sub-scale assesses one of the six core abilities to form the composite construct of self-management: (1) take initiatives (be instrumental or self-motivating in realizing aspects of well-being); (2) invest in resources for long-term benefits; (3) maintain variety in resources (achieve and maintain various resources for each dimension of well-being); (4) ensure resource multi-functionality (gain and maintain resources or activities that serve multiple dimensions of well-being simultaneously and in a mutually reinforcing way); (5) self-efficaciously manage resources (gain and maintain a belief in personal competence to achieve well-being); and (6) maintain a positive frame of mind. Each of these abilities directly relates to the dimensions of well-being specified in the SPF theory: physical well-being (comfort and stimulation) and social well-being (affection, behavioral confirmation, and status) | The scale is a very comprehensive tool to explore patients’ attitudes, beliefs, competences and self-efficacy perceptions when managing their health and treatment | The scale is quite long and complex, although articulated into several sub-scales. Furthermore. the scale is only related to engagement in self-management | The SMAS is usable to assess patients’ skills and attitude in self-management |

| Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease Scale (SEMCD) [54] | The SEMCD scale was developed to assess outcomes of the Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP), which aimed to enhance patients’ self-efficacy for chronic disease self-management. The current measure is built from six of ten items from the original Self-efficacy to Manage Symptoms and the Self-efficacy to Manage Disease scales (2 of 10 scales designed to evaluate the Stanford program). | German, Persian, and an international validation study of both the English and Spanish versions all show the SEMCD to be uni-dimensional and internally consistent | Despite extensive use, little information is available on how the original scales were designed or items selected. | The scale is usable to assess patients’ behavioural ability to manage the disease and their self-effectiveness in doing it. |

| Hopkins Rehabilitation Engagement Rating Scale (HRERS) [55] | Hopkins Rehabilitation Engagement Rating Scale (HRERS) provides an evaluation of the degree of patients’ participation in the rehabilitation process. It consists of a 5-item measurement with which to assess clinicians’ evaluation of patients’ engagement in acute rehabilitation services | The scale is widely used in rehabilitation settings and enables clinicians to rate their patients’ level of participation on the basis of agreed standards | The measurement is only concerned with the rehabilitation setting and only provides a clinician rating of patient engagement | The scale was developed for the acute rehabilitation setting |

| Family and Caregiver Engagement Assessment Scales | ||||

| Preparedness for Caregiving Scale[56] | An 8-item questionnaire (validated on a psychometric level) created to assess the extent to which the caregiver perceives him/herself as prepared to deal with the assistive role on various levels (physical care, emotional support, stress management). | The scale furnishes an adequate measurement of the caregiver’s competences in care-taking as well as his/her psychological adjustment to assuming this role. | The scale was developed and validated for the neurological and oncological field and has never been used in other therapeutic areas. | The scale is devoted to assessing caregivers’ experience in neurological and oncological settings |

| Parent-Patient Activation Measure [57] | This is the caregiver version of the 13-item scale that measures the patient’s activation in self-managing his/her healthcare. This scale assesses the level of the caregiver’s activation, evaluating his/her knowledge, his/her perceived self-efficacy and his/her desire to take an active role in managing the healthcare of his/her loved one. | The scale is similar to the one aimed at measuring patient activation and allows to mirror patients’ and caregivers’ experiences | The scale is specific for the pediatric area. | The scale is the analogue of PAM version for patients and it is dedicated to parents of pediatric patients |

| Scales for the Assessment of Healthcare Professionals’ Attitudes towards the Principles of Patient & Caregiver Engagement | ||||

| Clinician Support for Patient Activation Measure – CS-PAM [58] | Instrument that allows assessment of the attitudes and beliefs of clinicians towards the activation of the person with chronic illness. | This measurement is similar to the ones aimed at measuring caregivers’ and patient’s activation and allows comparisons and mirroring of the activation level among these actors. | The scale does not assess actual clinicians’ behaviors. | The scale is the analogue of the PAM version for patients and it measures healthcare professionals’ attitudes and beliefs about patients’ activation |

| Self-Management Support (SMS) Scale [59] | Behavioural scale intended to measure the extent to which clinicians use strategies to improve the patient’s self-management competences. | Offers a list of prototypical behaviors that characterize the clinician’s abilities to motivate and educate the person in self-management. | It does not assess the clinician’s attitudes and his/her value orientation to Engagement. | The scale is useful to rate the number of HP behaviors dedicated to improve patients’ engagement |

| Target | Patient Engagement Strategies | Examples of Methods and Tools Suggested by Experts |

|---|---|---|

| Patient and Family | Give information about the different aspects of the care | Leaflets, books, multimedia platforms, learning video, websites, seminars/workshop/conferences |

| Motivate in improving their awareness about their functioning, their needs and their ability to change | Motivational interviews, goal setting, problem solving techniques, wellness plans, behavioural counselling | |

| Improve the self-awareness | Mindfulness interventions, narrrative diaries, expressive writing | |

| Support the psychological and emotional elaboration | Psychological consultations, self-help groups/patients’ groups, positive psychology | |

| Communicate with the clinicians | Question asking, decision aids, teach back methods | |

| Self-monitor | Therapies patients’ diaries | |

| Protect patients’ rights | Patient advocacy group, informed consent | |

| Promote the networking | Patient associations, patient voluntary associations, caregivers associations | |

| Health Professionals | Sensitize clinicians to the value of patient engagement | Scientific literature sharing and discussion, seminars, workshops, conferences, continuing and distance education |

| Train clinicians to communicate more effectively with their patient | Clinical cases, role playing, consultations’ simulations | |

| Support to the professional identity and role | Leadership trainings, professional identity consultancy, professional counselling | |

| Promote the clinicians’ wellbeing and work engagement | Health promotion interventions, burnout assessment, work engagement interventions, psychological consultancy | |

| Healthcare Organization | Foster a multidisciplinary approach to the care | Multidisciplinary equipe, interdisciplinary team meetings |

| Facilitate the continuity of care as an essential part of enabling better health outcomes, through the boost of patient engagement | Case managers, personalized care plans, integrated care models, Electronic Health Records, Personalized Health Records, Bedsides shift reports | |

| Measure the performance and the level of patient engagement | Patient engagement measure tools (PAM, PHE-s, Altarum Consumer Engagement Scale), patient satisfaction measure, healthcare costs monitoring, public reports, accountability | |

| Promote the active participation of all the healthcare stakeholders (i.e., patients and family organizations, clinical societies, policy makers….) | Action research, groups of participative governance, focus group |

| Summary of Main Consensus Statements and Recommendations |

|---|

| “Engagement” in the clinical care field of chronicity is an umbrella concept that includes and extends beyond other concepts such as adherence, compliance, empowerment, activation, health literacy, shared decision making. Engagement is a complex process that arises from the combination of different dimensions and individual, relational, organizational, social, economic and political factors that connote the quality of life of the patient |

| The formal/informal caregiver - especially in the case of elderly people or young children with severe disabilities and/or in clinical conditions that make them less autonomous in their health management - plays a key role in the process of engagement |

| The evaluation and measurement of the engagement of all actors involved in the care process (patients with chronic illnesses, caregivers and healthcare professionals in the social field) is a factor crucial for enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of the clinical care interventions |

| The training and sensitization of health professionals and healthcare organizations and policy makers about the principles of engagement |

| Technologies can enable the process of engagement and supplement other non-technological intervention strategies; but they are not an alternative to the therapeutic relationship |

| The possible results expected from engagement are: facilitation of the patient in taking care of his/her health, improvement of clinical results, improvement of lifestyle and reduction of healthcare costs, greater integration and continuity of the healthcare and social journey. However, the efficacy testing of these outcomes in the current literature is still quantitatively limited and methodologically weak: this may be due to the still “infancy” of academic research on the topic but also by the lack of investment on this crucial sector. Further joint research activities are needed internationally in order to produce evidence on the outcomes of Engagement initiatives. |

| It is necessary to promote further quality research in the field of efficacy testing of the methodologies and the impact of engagement in health and social services and in clinical care practice |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Graffigna, G.; Barello, S.; Riva, G.; Corbo, M.; Damiani, G.; Iannone, P.; Bosio, A.C.; Ricciardi, W. Italian Consensus Statement on Patient Engagement in Chronic Care: Process and Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114167

Graffigna G, Barello S, Riva G, Corbo M, Damiani G, Iannone P, Bosio AC, Ricciardi W. Italian Consensus Statement on Patient Engagement in Chronic Care: Process and Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(11):4167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114167

Chicago/Turabian StyleGraffigna, Guendalina, Serena Barello, Giuseppe Riva, Massimo Corbo, Gianfranco Damiani, Primiano Iannone, Albino Claudio Bosio, and Walter Ricciardi. 2020. "Italian Consensus Statement on Patient Engagement in Chronic Care: Process and Outcomes" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 11: 4167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114167

APA StyleGraffigna, G., Barello, S., Riva, G., Corbo, M., Damiani, G., Iannone, P., Bosio, A. C., & Ricciardi, W. (2020). Italian Consensus Statement on Patient Engagement in Chronic Care: Process and Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114167