In the Name of Family Medicine: A Nationwide Survey of Registered Names of Family Medicine Clinics in Taiwan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Study Design and Data Extraction

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Clinics of Western Medicine in Taiwan

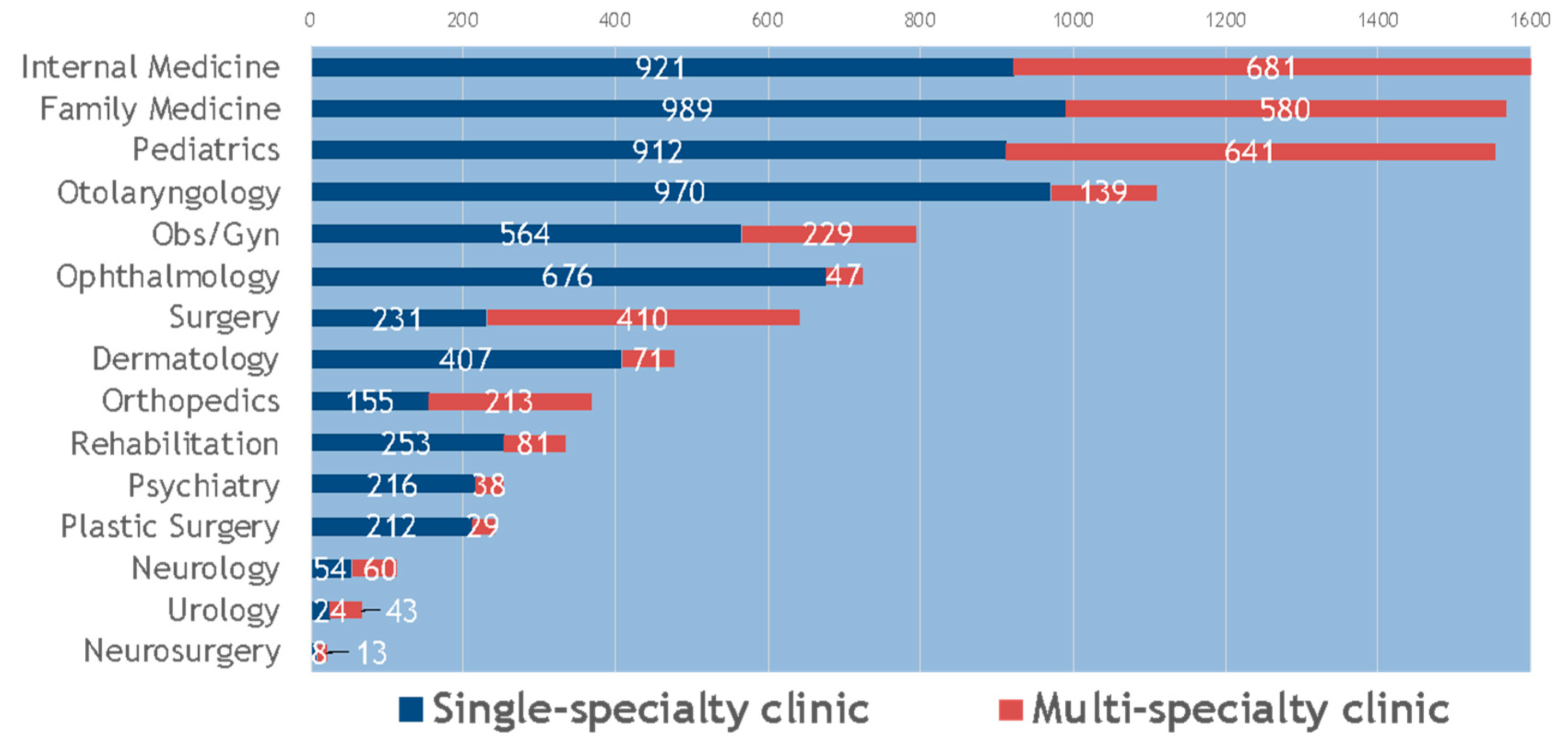

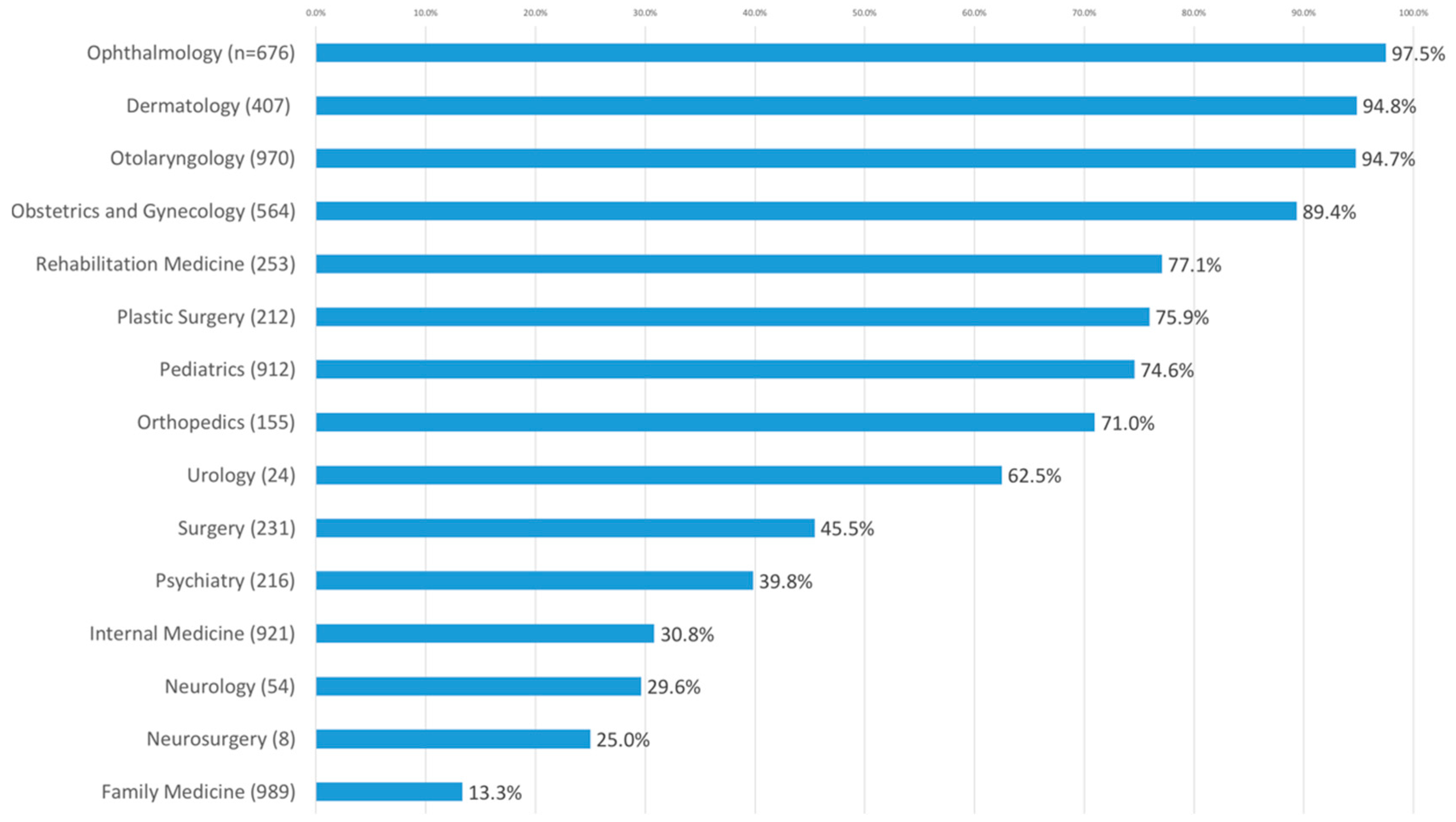

3.2. Clinic Names that Included Their Own Specialty

3.3. Single-Specialty Clinic Names Including a Term for “Family Medicine”

4. Discussion

4.1. Principle Findings

4.2. Features of Registered Clinic Names in Taiwan

4.3. The Branding of Family Medicine

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Future of Family Medicine Project Leadership Committee. The future of family medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann. Fam. Med. 2004, 2, S3–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, T. Is family medicine a specialty? Yes. Can. Fam. Physician 2007, 53, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stein, H.F. Family medicine’s identity: being generalists in a specialist culture? Ann. Fam. Med. 2006, 4, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzinga, H. A new identity for family medicine: physicians for the underserved. Fam. Pract. Manag. 2005, 12, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.J. The South Korean health care system. Jpn. Med. Assoc. J. 2009, 52, 206–209. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.Y.; Majeed, A.; Kuo, K.N. An overview of the healthcare system in Taiwan. London J. Prim. Care (Abingdon) 2010, 3, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.; Pawlikowska, T.; Schweyer, F.X.; López-Roig, S.; Bélanger, E.; Burns, J.; Hugé, S.; Pastor-Mira, M.Î.; Tellier, P.-P.; Spencer, S.; et al. Family physicians’ professional identity formation: a study protocol to explore impression management processes in institutional academic contexts. BMC Med. Educ. 2014, 14, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, P.A.; Waller, E.; Eiff, M.P.; Saultz, J.W.; Jones, S.; Fogarty, C.T.; Corboy, J.E.; Green, L. Measuring family physician identity: the development of a new instrument. Fam. Med. 2013, 45, 708–718. [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu, M.D.; Rioux, M.; Rocher, G.; Samson, L.; Boucher, L. Family practice: professional identity in transition. A case study of family medicine in Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.; Tellier, P.P.; Bélanger, E. Exploring professional identification and reputation of family medicine among medical students: a Canadian case study. Educ. Prim. Care 2012, 23, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, I.; Wright, B.; Brenneis, F.; Brett-Maclean, P.; McCaffrey, L. Why would I choose a career in family medicine? Reflections of medical students at 3 universities. Can. Fam. Physician 2007, 53, 1956–1957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ozcakir, A.; Yaphe, J.; Ercan, I. Perceptions of family medicine and career choice among first year medical students: a cross-sectional survey in a Turkish medical school. Coll. Antropol. 2007, 31, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hansen, S.E.; Mathieu, S.S.; Biery, N.; Dostal, J. The emergence of family medicine identity among first-year residents: a qualitative study. Fam. Med. 2019, 51, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ie, K.; Tahara, M.; Murata, A.; Komiyama, M.; Onishi, H. Factors associated to the career choice of family medicine among Japanese physicians: the dawn of a new era. Asia Pac. Fam. Med. 2014, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, C.Y.; Hung, Y.T.; Chuang, Y.L.; Chen, Y.J.; Weng, W.S.; Liu, J.S.; Liang, K.Y. Incorporating development stratification of Taiwan townships into sampling design of large scale health interview survey. J. Health Manag. 2006, 4, 1–22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare. National Health Insurance Annual Statistical Report 2018. Available online: https://www.mohw.gov.tw/cp-4574-49817-2.html (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Chu, F.Y.; Dai, Y.X.; Liu, J.Y.; Chen, T.J.; Chou, L.F.; Hwang, S.J. A doctor’s name as a brand: a nationwide survey on registered clinic names in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.X.; Chen, M.H.; Chen, T.J. Low prevalence of the use of the Chinese term for ‘psychiatry’ in the names of community psychiatry clinics: a nationwide study in Taiwan. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2016, 62, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.X.; Chen, T.J.; Lin, M.H. Branding palliative care units by avoiding the terms “palliative” and “hospice”: a nationwide study in Taiwan. Inquiry 2017, 54, 46958016686449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, N.B., Jr.; Schmittling, G.; Ostergaard, D.; Graham, R. Specialty practice of family practice residency graduates, 1969 through 1993: a national study. JAMA 1996, 275, 713–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwan Association of Family Medicine. Association Historiography. Available online: https://www.tafm.org.tw/ehc-tafm/s/w/Association/article/e437d4cf75184b89be4221205c4d040e (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Brown, C. Recognition of family physicians as experts rather than gatekeepers requires “cultural shift”. CMAJ 2018, 190, E550–E551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Roig, S.; Pastor, M.Á.; Rodríguez, C. The reputation and professional identity of family medicine practice according to medical students: a Spanish case study. Aten. Primaria 2010, 42, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavendran, S.; Inbaraj, L.R. Do family physicians suffer an identity crisis? A perspective of family physicians in Bangalore city. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2018, 7, 1274–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selva Olid, A.; Zurro, A.M.; Villa, J.J.; Hijar, A.M.; Tuduri, X.M.; Puime, Á.O.; Dalmau, G.M.; Alonso-Coello, P.; for the Universidad y Medicina de Familia Research Group (UNIMEDFAM). Medical students’ perceptions and attitudes about family practice: a qualitative research synthesis. BMC Med. Educ. 2012, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendling, A.L.; Wudyka, A.E.; Phillips, J.P.; Levine, D.L.; Mulhem, E.; Neale, A.V.; Morley, C.P. RU4PC? Texting to quantify feedback about primary care and its relationship with student career interest. Fam. Med. 2016, 48, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, B.; Scott, I.; Woloschuk, W.; Brenneis, F.; Bradley, J. Career choice of new medical students at three Canadian universities: family medicine versus specialty medicine. CMAJ 2004, 170, 1920–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Lim, K.; Park, E.W.; Choi, E.Y.; Cheong, Y.S. Patients’ perceived quality of family physicians’ primary care with or without ‘Family Medicine’ in the clinic name. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2016, 37, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Premji, K.; Upshur, R.; Légaré, F.; Pottie, K. Future of family medicine: role of patient-centred care and evidence-based medicine. Can. Fam. Physician 2014, 60, 409–412. [Google Scholar]

- Vanasse, A.; Orzanco, M.G.; Courteau, J.; Scott, S. Attractiveness of family medicine for medical students: influence of research and debt. Can. Fam. Physician 2011, 57, e216–e227. [Google Scholar]

- Gladu, R.; Nieman, L.Z.; Goodrich, T.J.; Groff, J.Y.; Velasquez, M.M. Family medicine month in a university-based program: establishing a family medicine identity. Fam. Med. 2002, 34, 164–166. [Google Scholar]

| Urbanization Level | Number of Single-Specialty Clinics of Family Medicine | Number of Single-Specialty Clinics of Family Medicine Containing the Specialty in the Clinic Name |

|---|---|---|

| Urban | 487 (100%) | 74 (15.2%) |

| Suburban | 349 (100%) | 44 (12.6%) |

| Rural | 153 (100%) | 14 (9.2%) |

| Total | 989 (100%) | 132 (13.3%) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.-A.; Cheng, S.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Yang, P.-C.; Chang, H.-T.; Lin, M.-H.; Chen, T.-J.; Chou, L.-F.; Hwang, S.-J. In the Name of Family Medicine: A Nationwide Survey of Registered Names of Family Medicine Clinics in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4062. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114062

Liu Y-A, Cheng S, Hsu Y-C, Yang P-C, Chang H-T, Lin M-H, Chen T-J, Chou L-F, Hwang S-J. In the Name of Family Medicine: A Nationwide Survey of Registered Names of Family Medicine Clinics in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(11):4062. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114062

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ya-An, Sally Cheng, Ya-Chuan Hsu, Po-Chin Yang, Hsiao-Ting Chang, Ming-Hwai Lin, Tzeng-Ji Chen, Li-Fang Chou, and Shinn-Jang Hwang. 2020. "In the Name of Family Medicine: A Nationwide Survey of Registered Names of Family Medicine Clinics in Taiwan" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 11: 4062. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114062

APA StyleLiu, Y.-A., Cheng, S., Hsu, Y.-C., Yang, P.-C., Chang, H.-T., Lin, M.-H., Chen, T.-J., Chou, L.-F., & Hwang, S.-J. (2020). In the Name of Family Medicine: A Nationwide Survey of Registered Names of Family Medicine Clinics in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4062. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114062