An Explanatory Model of Sexual Satisfaction in Adults with a Same-Sex Partner: An Analysis Based on Gender Differences

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Will personal and interpersonal variables associate (directly and/or indirectly) with sexual satisfaction?

- Will the explanatory models show gender differences?

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Differences by Sex

3.2. Bivariate Correlations

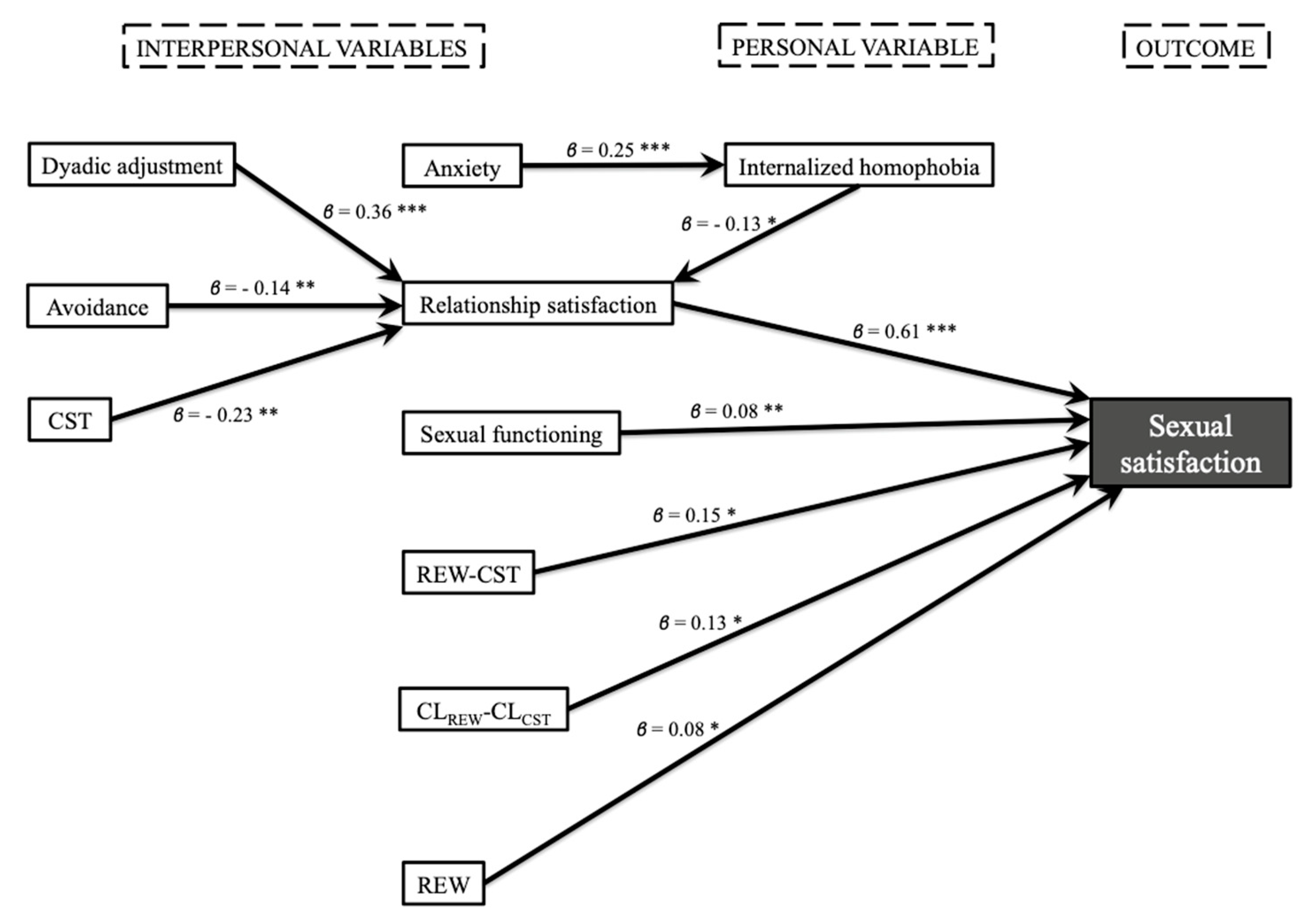

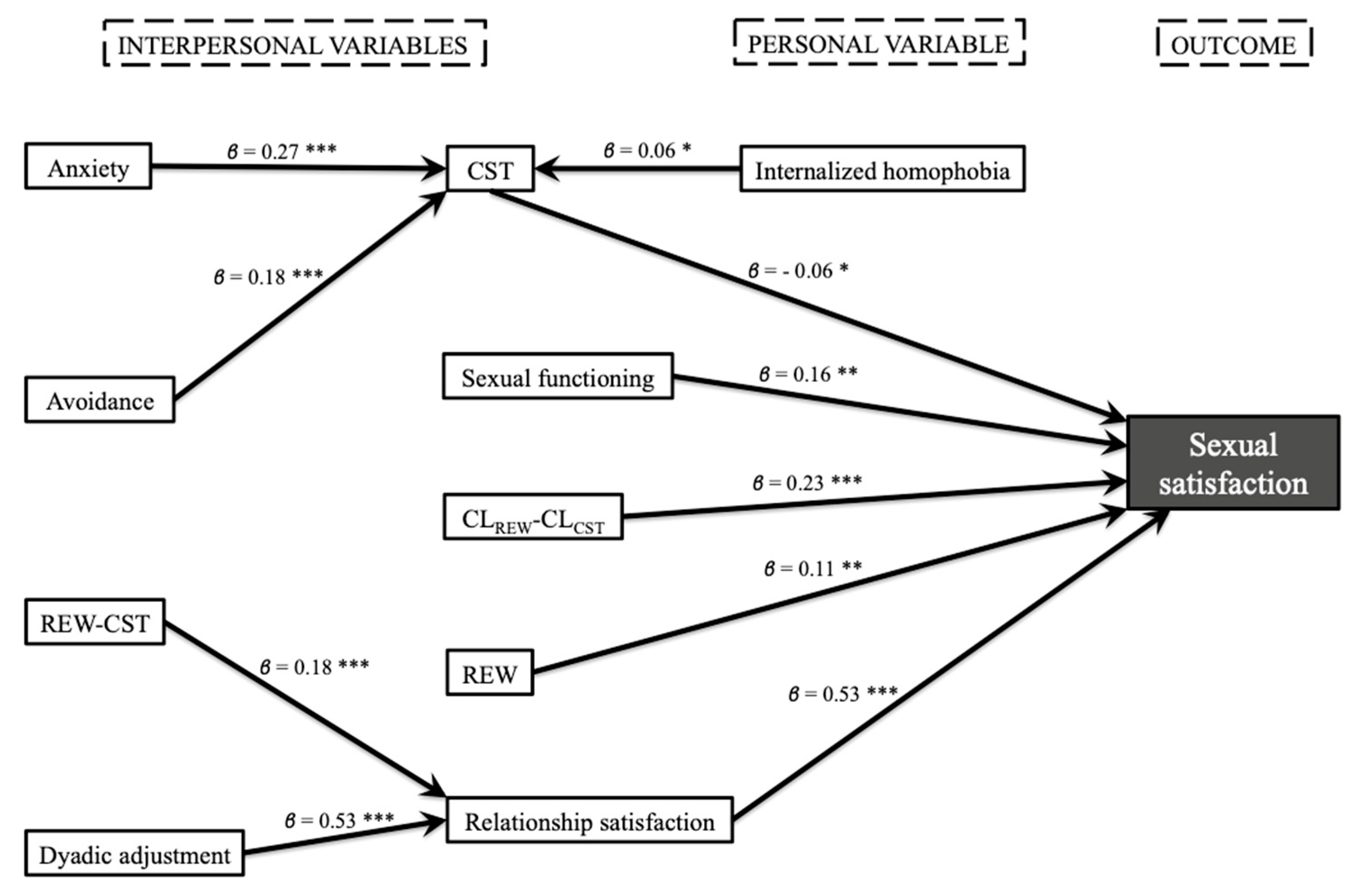

3.3. Testing the Models

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Measuring Sexual Health: Conceptual and Practical Considerations and Related Indicators; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70434/who_rhr_10.12_eng.pdf;jsessionid=67CF1DCDE6D56A85082C5101F8854FAB?sequence=1 (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- Byers, E.S.; Rehman, U.S. Sexual well-being. In APA, Handbook of Sexuality and Psychology; Tolman, L.D., Hamilton, L.M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, WA, USA, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 317–337. [Google Scholar]

- Calvillo, C.; Sánchez-Fuentes, M.M.; Sierra, J.C. Revisión sistemática sobre la satisfacción sexual en parejas del mismo sexo [Systematic review of sexual satisfaction in same-sex couples]. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Salud 2018, 9, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fuentes, M.M.; Santos-Iglesias, P.; Sierra, J.C. A systematic review of sexual satisfaction. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2014, 14, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrance, K.; Byers, E.S. Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: The Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction. Pers. Relatsh. 1995, 2, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoal, P.M.; Narciso, I.d.S.B.; Pereira, N.M. What is sexual satisfaction? Thematic analysis of lay people’s definitions. J. Sex Res. 2013, 51, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GAB. Working Definition of Sexual Pleasure. Available online: http://www.gab-shw.org/our-work/working-definition-of-sexual-pleasure/ (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Budge, S.L.; Katz-Wise, S.L. Sexual minorities’ gender norm conformity and sexual satisfaction: The mediating effects of sexual communication, internalized stigma, and sexual narcissism. Int. J. Sex. Health 2019, 31, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleishman, J.M.; Crane, B.; Koch, P.B. Correlates and predictors of sexual satisfaction for older adults in same-sex relationships. J. Homosex. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepler, D.K.; Smendik, J.M.; Cusik, K.M.; Tucker, D.R. Predictors of sexual satisfaction for partnered lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2018, 5, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoal, P.M.; Shaughnessy, K.; Almeida, M.J. A thematic analysis of a sample of partnered lesbian, gay, and bisexual people´s concepts of sexual satisfaction. Psychol. Sex. 2019, 10, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyar, C.; Newcomb, M.E.; Mustanski, B.; Whitton, S.W. A Structural equation model of sexual satisfaction and relationship functioning among sexual and gender minority individuals assigned female at birth in diverse relationships. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological models of human development. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 2nd ed.; Husén, T., Postlethwaite, T.N., Eds.; Pergamon, Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 1994; Volume 3, pp. 1643–1647. [Google Scholar]

- Arcos-Romero, A.I.; Sierra, J.C. Revisión sistemática sobre la experiencia subjetiva del orgasmo [Systematic review of the subjective experience of orgasm]. Rev. Int. Androl. 2018, 16, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos-Romero, A.I.; Sierra, J.C. Factors associated with subjective orgasm experience in heterosexual relationships. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2020, 46, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, A.W.; Lehavot, K.; Simoni, J.M. Ecological models of sexual satisfaction among lesbian/bisexual and heterosexual women. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2009, 38, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Fuentes, M.M.; Salinas, J.M.; Sierra, J.C. Use of an ecological model to study sexual satisfaction in a heterosexual Spanish sample. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2016, 45, 1973–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haseli, A.; Shariati, M.; Nazari, A.M.; Keramat, A.; Emamian, M.H. Infidelity and its associated factors: A systematic review. J. Sex. Med. 2019, 16, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herek, G.M. The psychology of sexual prejudice. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2000, 9, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herek, G.M. Beyond “homophobia”: Thinking about sexual prejudice and stigma in the twenty-first century. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2004, 1, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyper, L.; Vanwesenbeeck, I. Examining sexual health differences between lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual adults: The role of sociodemographics, sexual behavior characteristics, and minority stress. J. Sex Res. 2011, 48, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss, 2nd ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1982; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Zapiain, J. Apego y Sexualidad; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sperling, M.B.; Berman, W.H. (Eds.) Attachment in Adults: Clinical and Developmental Perspectives; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, K.A.; Clark, C.L.; Shaver, P.R. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In Attachment Theory and Close Relationships; Simpson, J.A., Rholes, W.S., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan, C.; Shaver, P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 51–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzer, B.; Campbell, L. Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Pers. Relatsh. 2008, 15, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-González, M.; Barrientos, J.; Gómez, F.; Meyer, I.H.; Bahamondes, J.; Cárdenas, M. Romantic attachment and relationship satisfaction in gay men and lesbians in Chile. J. Sex Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, K.P.; Vowels, L.M.; Murray, S.H. The impact of attachment style on sexual satisfaction and sexual desire in a sexually diverse sample. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2018, 44, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suschinsky, K.D.; Huberman, J.S.; Maunder, L.; Brotto, L.A.; Hollenstein, T.; Chivers, M.L. The relationship between sexual functioning and sexual concordance in women. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2019, 45, 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvillo, C.; Sánchez-Fuentes, M.M.; Parrón, T.; Sierra, J.C. Validation of the Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire in adults with a same-sex partner. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farero, A.; Bowles, R.; Blow, A.; Ufer, L.; Kees, M.; Guty, D. Rasch analysis of the Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (RDAS) with military couples. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2019, 41, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busby, D.M.; Christensen, C.; Crane, D.R.; Larson, J.H. A revision of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale for use with distressed and nondistressed couples: Construct hierarchy and multidimensional scales. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 1995, 21, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanier, G.B. The measurement of marital quality. J. Sex Marital Ther. 1979, 5, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallis, E.E.; Rehman, U.S.; Woody, E.Z.; Purdon, C. The longitudinal association of relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction in long-term relationships. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.N.; Byers, E.S. Minority stress, protective factors, and sexual functioning of women in a same-sex relationship. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fuentes, M.M.; Sierra, J.C. Sexual satisfaction in a heterosexual and homosexual Spanish sample: The role of socio-demographic characteristics, health indicators, and relational factors. Sex. Relation. Ther. 2015, 30, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, D.; Chartrand, E.; Simard, M.-C.; Bouthillier, D.; Bégin, J. Conflict, social support, and relationship quality: An observational study of heterosexual, gay male, and lesbian couples’ communication. J. Fam. Psychol. 2003, 17, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, M.; LoPresti, B.J.; Denes, A. Exploring trait affectionate communication and post sex communication as mediators of the association between attachment and sexual satisfaction. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2019, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.C.; Moyano, N.; Vallejo-Medina, P.; Gómez-Berrocal, C. An abridged Spanish version of Sexual Double Standard Scale: Factorial structure, reliability and validity evidence. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2018, 18, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsey, A.C.; Pomeroy, W.B.; Martin, C.E. Sexual Behavior in the Human Male; Indiana University Press (Orig. 1948): Bloomington, IN, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, A.P.; Weinberg, M.S. Homosexualities: A Study of Diversity among Men and Women; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega López, A. Agresión en Parejas Homosexuales en España y Argentina: Prevalencias y Heterosexismo. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, M.W.; Rosser, B.R.S.; Neumaier, E.R.; Positive Connections Team. The relationship of internalized homonegativity to unsafe sexual behavior in HIV seropositive men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2008, 20, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, M.; Russell, D.W.; Mallinckrodt, B.; Vogel, D.L. The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR)-Short Form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess. 2007, 88, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvillo, C.; Sánchez-Fuentes, M.M.; Parrón, T.; Sierra, J.C. Validación de la versión breve de la Experiences in Close Relationship en adultos con pareja del mismo sexo [Validation of the short version of the Experiences in Close Relationship in adults with a same-sex partner]. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Ev. 2020, 2, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, M.; Rankin, M.A.; Alpert, J.E.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Worthington, J.J. An open trial of oral sildenafil in antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. Psychother. Psychosom. 1998, 67, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.C.; Vallejo-Medina, P.; Santos-Iglesias, P.; Lameiras Fernández, M. Validación del Massachussets General Hospital-Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (MGH-SFQ) en población española [Validation of the Massachusetts General Hospital-Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (MGH-SFQ) in a Spanish population]. Aten. Primaria 2012, 44, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanier, G.B. DAS. Escala de Ajuste Diádico; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Iglesias, P.; Vallejo-Medina, P.; Sierra, J.C. Propiedades psicométricas de una versión breve de la Escala de Ajuste Diádico en muestras españolas [Development and validation of a short version of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale in Spanish samples]. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2009, 9, 501–517. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrance, K.; Byers, E.S.; Cohen, J.N. Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire. In Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures, 3rd ed.; Fisher, T.D., Davis, C.M., Yarber, W.L., Davis, S.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 525–530. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Fuentes, M.M.; Santos-Iglesias, P.; Byers, E.S.; Sierra, J.C. Validation of the Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire in a Spanish sample. J. Sex Res. 2015, 52, 1028–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fuentes, M.M.; Santos-Iglesias, P. Sexual satisfaction in Spanish heterosexual couples: Testing the Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2016, 42, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R; RStudio, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2018; Available online: http//www.rstudio.com (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J. The strengths and limitations of the statistical modeling of complex social phenomenon: Focusing on SEM, path analysis, or multiple regression models. Int. J. Soc. Behav. Educ. Econ. Bus. Ind. Eng. 2015, 9, 1594–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McAlister, A.L.; Krosnick, J.A.; Milburn, M.A. Causes of adolescent cigarette smoking: Tests of a structural equation model. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1984, 47, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, A.; Nitzl, C.; Kraus, F.; Förstner, R. Cost estimation of an asteroid mining mission using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Acta Astronaut. 2020, 167, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, M.A.Y. Examining the role of transformational leadership and entrepreneurial orientation on employee retention with moderating role of competitive advantage. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gana, K.; Broc, G. Structural Equation Modeling with Lavaan; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra, A.; Bentler, P.M. Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In Latent Variable Analysis: Applications to Developmental Research; Von Eye, A., Clogg, C.C., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 399–419. [Google Scholar]

- Sherry, A. Internalized homophobia and adult attachment: Implications for clinical practice. Psychotherapy 2007, 44, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D.M.; Meyer, I.H. Internalized homophobia and relationship quality among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. J. Couns. Psychol. 2009, 56, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-González, M.; Barrientos, J.; Cárdenas, M.; Espinoza, M.F.; Quijada, P.; Rivera, C.; Tapia, P. Romantic attachment and life satisfaction in a sample of gay men and lesbians in Chile. Int. J. Sex. Health 2016, 28, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbay, N.; Lafontaine, M.F. Understanding the relationship between attachment, caregiving, and same sex intimate partner violence. J. Fam. Violence 2017, 32, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, J.J.; Selterman, D.; Fassinger, R.E. Romantic attachment and relationship functioning in same-sex couples. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridge, S.R.; Feeney, J.A. Relationship history and relationship attitudes in gay males and lesbians: Attachment styles and gender differences. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 1998, 32, 848–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neil, J.M. Summarizing 25 years of research on men’s gender role conflict using the Gender Role Conflict Scale: New research paradigms and clinical implications. Couns. Psychol. 2008, 36, 358–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R.-J.; Mitchell, V. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual issues in couple Therapy. In Clinical Handbook of Couple Therapy, 5th ed.; Gurman, A.S., Lebow, J.L., Snyder, D.K., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 489–511. [Google Scholar]

- Colgan, P. Treatment of identity and intimacy issues in gay males. J. Homosex. 1987, 14, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGahuey, C.A.; Gelenberg, A.J.; Laukes, C.A.; Moreno, F.A.; Delgado, P.L.; McKnight, K.M.; Manber, R. The Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX): Reliability and validity. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2000, 26, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fuentes, M.M.; Moyano, N.; Granados, R.; Sierra, J.C. Validation of the Spanish version of the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX) using self-reported and physiological measures. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Salud 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.; Pereira, H.; Monteiro, S.; Esgalhado, G.; Afonso, R.M.; Loureiro, M.; Delfina, F.; Garcia, N. The importance of biomedical indicators in sexual functioning in healthy Portuguese adults. Rev. Int. Androl. 2019, 17, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moret, L.B.; Glaser, B.A.; Page, R.C.; Bargeron, E.F. Intimacy and sexual satisfaction in unmarried couple relationships: A pilot study. Fam J. Alex Va 1998, 6, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.B.; Ritchie, L.; Knopp, K.; Rhoades, G.K.; Markman, H.J. Sexuality within female same-gender couples: Definitions of sex, sexual frequency norms, and factors associated with sexual satisfaction. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2018, 47, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.L. Attachment identity as a predictor of relationship functioning among heterosexual and sexual-minority women. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommantico, M.; Donizzetti, A.R.; Parrello, S.; De Rosa, B. Gay and lesbian couples’ relationship quality: Italian validation of the Gay and Lesbian Relationship Satisfaction Scale (GLRSS). J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2019, 23, 326–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitalnick, J.S.; McNair, L.D. Couples therapy with gay and lesbian clients: An analysis of important clinical issues. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2005, 31, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldridge, N.S.; Gilbert, L.A. Correlates of relationship satisfaction in lesbian couples. Psychol. Women Q. 1990, 14, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, K.M.; Deluty, R.H. Social support, coming out, and relationship satisfaction in lesbian couples. J. Lesbian Stud. 2000, 4, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, M.M.; Nobre, P. Distressing sexual problems and dyadic adjustment in heterosexuals, gay men, and lesbian women. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2016, 42, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova, J.V.; Gee, C.B.; Warren, L.Z. Emotional skillfulness in marriage: Intimacy as a mediator of the relationship between emotional skillfulness and marital satisfaction. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 24, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindia, K.; Allen, M. Sex differences in self-disclosure: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.N.; Byers, E.S.; Walsh, L.P. Factors influencing the sexual relationships of lesbian and gay men. Int. J. Sex. Heal. 2008, 20, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, K.R.; Meston, C.M. The association between sexual costs and sexual satisfaction in women: An exploration of the Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 2011, 20, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Schachner, D.A.; Shaver, P.R. Attachment dimensions and sexual motives. Pers. Relatsh. 2004, 11, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradi, H.J.; Noordhof, A.; Dingemanse, P.; Barelds, G.P.H.; Kamphuis, J.H. Actor and partner effects of attachment on relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction across the genders: An APIM approach. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2017, 43, 700–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birnbaum, G.E. Attachment orientations, sexual functioning, and relationship satisfaction in a community sample of women. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2007, 24, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, P.R.; Hazan, C. A biased overview of the study of love. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 1988, 5, 473–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impett, E.A.; Peplau, L.A. Why some women consent to unwanted sex with a dating partner: Insights from Attachment theory. Psychol. Women Q. 2002, 26, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, B.A.; Goldfried, M.R.; Davila, J. The relationship between experiences of discrimination and mental health among lesbians and gay men: An examination of internalized homonegativity and rejection sensitivity as potential mechanism. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 80, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thies, K.E.; Starks, T.J.; Denmark, F.L.; Rosenthal, L. Internalized homonegativity and relationship quality in same-sex romantic couples: A test of mental health mechanism and gender as a moderator. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2016, 3, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, J.J.; Fassinger, R.E. Self-acceptance and self-disclosure of sexual orientation in lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: An attachment perspective. J. Couns. Psychol. 2003, 50, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingoglia, S.; Miano, P.; Guajana, M.E.; Vitale, A. Secure attachment and individual protective factors against internalized homophobia. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdek, L.A. Relationship outcomes and their predictors: Longitudinal evidence from heterosexual married, gay cohabiting, and lesbian cohabiting couples. J. Marriage Fam. 1998, 60, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, K.P.; Mailhausen, R.R.; Maitland, S.B. The impact of sexual compatibility on sexual and relationship satisfaction in a sample of young adult heterosexual couples. Sex. Relation. Ther. 2013, 28, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vowels, L.M.; Mark, K.P. Relationship and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal actor-partner interdependence model approach. Sex. Relation. Ther. 2020, 35, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, E.S. Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study of individuals in long-term relationships. J. Sex Res. 2005, 42, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haavio-Mannila, E.; Kontula, O. Correlates of increased sexual satisfaction. Arch. Sex. Behav. 1997, 26, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, K.P.; Jozkowski, K.N. The mediating role of sexual and nonsexual communication between relationship and sexual satisfaction in a sample of college-age heterosexual couples. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2013, 39, 410–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, I.M.; Schlagintweit, H.E.; Nobre, P.J.; Rosen, N.O. Sexual well-being and perceived stress in couples transitioning to parenthood: A dyadic analysis. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2019, 19, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano, N.; Vallejo-Medina, P.; Sierra, J.C. Sexual Desire Inventory: Two or three dimensions? J. Sex Res. 2017, 54, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos-Romero, A.I.; Sierra, J.C. Factorial invariance, differential item functioning, and norms of the Orgasm Rating Scale. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2019, 19, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalheira, A.A.; Costa, P.A. The impact of relational factors on sexual satisfaction among heterosexual and homosexual men. Sex. Relat. Ther. 2015, 30, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Men (n = 410) | Women (n = 410) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | M (SD) | Rank | M (SD) | t/χ2 | |

| Age (years) | 18–66 | 29.24 (9.84) | 18–58 | 29 (8.57) | 0.36 |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | ||||

| First sexual relation (years) | 16.52 (3.82) | 17.55 (3.12) | −4.21 *** | ||

| Duration of the relationship with current partner (months) | 47.70 (56.75) | 46.90 (50.32) | 0.21 | ||

| Me | M (SD) | Me | M (SD) | ||

| Number of sexual partners | 11.50 | 32.18 (66.03) | 5 | 7.51 (10.73) | 7.46 *** |

| Nationality | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Spanish | 225 (54.90) | 247 (60.20) | 2.41 | ||

| Other Hispanic countries | 185 (45.10) | 163 (39.80) | |||

| Education level | |||||

| Basic | 6 (1.50) | 10 (2.4) | 1.32 | ||

| Intermediate | 113 (27.60) | 105 (25.60) | |||

| Higher | 291 (71) | 295 (72) | |||

| Cohabit with current partner | |||||

| Yes | 232 (56.60) | 231 (56.30) | 0.005 | ||

| No | 178 (43.40) | 179 (43.70) | |||

| Variables | Men (n = 410) | Women (n = 410) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | M (SD) | M (SD) | p | |

| Internalized homophobia | 4–28 | 6.50 (4.64) | 6.18 (4.33) | 0.309 |

| Anxiety | 6–42 | 20.88 (8.09) | 18.37 (7.63) | <0.001 |

| Avoidance | 6–42 | 13.50 (6.27) | 10.84 (5.07) | <0.001 |

| Sexual functioning | 0–20 (Men) 0–16 (Women) | 13.75 (3.27) | 10.20 (2.46) | <0.001 |

| Dyadic adjustment | 12–75 | 61.01 (7.96) | 63.28 (6.81) | <0.001 |

| Sexual satisfaction | 5–35 | 29.99 (6.35) | 32.10 (4.30) | <0.001 |

| Relationship satisfaction | 5–35 | 30.48 (6.35) | 32.11 (4.68) | <0.001 |

| REW-CST | from −8 to +8 | 3.80 (3.53) | 5.07 (3.06) | <0.001 |

| CLREW-CLCST | from −8 to + 8 | 3.10 (3.44) | 4.60 (3.10) | <0.001 |

| REW | 0–58 | 43.63 (7.92) | 44.55 (6.52) | 0.070 |

| CST | 0–58 | 15.58 (9.07) | 13.02 (7.57) | <0.001 |

| Variables | Outcome | Personal Variable | Interpersonal Variables | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| 1. Sexual satisfaction | 1 | −0.18 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.36 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.77 ** | 0.59 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.46 ** | −0.48 ** | −0.05 |

| 2. Internalized homophobia | −0.22 ** | 1 | 0.25 ** | 0.28 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.27 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.10 * | −0.08 | 0.07 | 0.20 ** |

| 3. Anxiety | −0.22 ** | 0.15 ** | 1 | 0.30 ** | −0.11 * | −0.29 ** | −0.27 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.24 | −0.18 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.09 |

| 4. Avoidance | −0.33 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.38 ** | 1 | −0.30 ** | −0.54 ** | −0.43 ** | −0.39 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.31 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.18 ** |

| 5. Sexual functioning | 0.42 ** | −0.04 | −0.15 ** | −0.17 ** | 1 | 0.38 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.36 ** | −0.42 ** | −0.11 * |

| 6. Dyadic adjustment | 0.44 ** | −0.26 ** | −0.37 ** | −0.51 ** | 0.24 ** | 1 | 0.55 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.43 ** | −0.42 ** | −0.05 |

| 7. Relationship satisfaction | 0.68 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.27 ** | −0.37 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.59 ** | 1 | 0.46 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.37 ** | −0.43 ** | −0.08 |

| 8. REW-CST | 0.49 ** | −0.09 | −0.27 ** | −0.33 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.38 ** | 1 | 0.80 ** | 0.48 ** | −0.54 ** | −0.07 |

| 9. CLREW-CLCST | 0.54 ** | −0.11 * | −0.30 ** | −0.30 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.72 ** | 1 | 0.40 ** | −0.46 ** | −0.05 |

| 10. REW | 0.39 ** | −0.08 | −0.25 ** | −0.17 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.30 ** | 1 | −0.62 ** | −0.05 |

| 11. CST | −0.44 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.30 ** | −0.37 ** | −0.34 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.47 ** | −0.39 ** | −0.62 ** | 1 | 0.09 |

| 12. Nationality | 0 | 0.14 ** | 0.05 | 0.16 ** | 0.09 | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.03 | 0 | −0.02 | 0.16 ** | 1 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calvillo, C.; Sánchez-Fuentes, M.d.M.; Sierra, J.C. An Explanatory Model of Sexual Satisfaction in Adults with a Same-Sex Partner: An Analysis Based on Gender Differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103393

Calvillo C, Sánchez-Fuentes MdM, Sierra JC. An Explanatory Model of Sexual Satisfaction in Adults with a Same-Sex Partner: An Analysis Based on Gender Differences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(10):3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103393

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalvillo, Cristóbal, María del Mar Sánchez-Fuentes, and Juan Carlos Sierra. 2020. "An Explanatory Model of Sexual Satisfaction in Adults with a Same-Sex Partner: An Analysis Based on Gender Differences" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 10: 3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103393

APA StyleCalvillo, C., Sánchez-Fuentes, M. d. M., & Sierra, J. C. (2020). An Explanatory Model of Sexual Satisfaction in Adults with a Same-Sex Partner: An Analysis Based on Gender Differences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103393