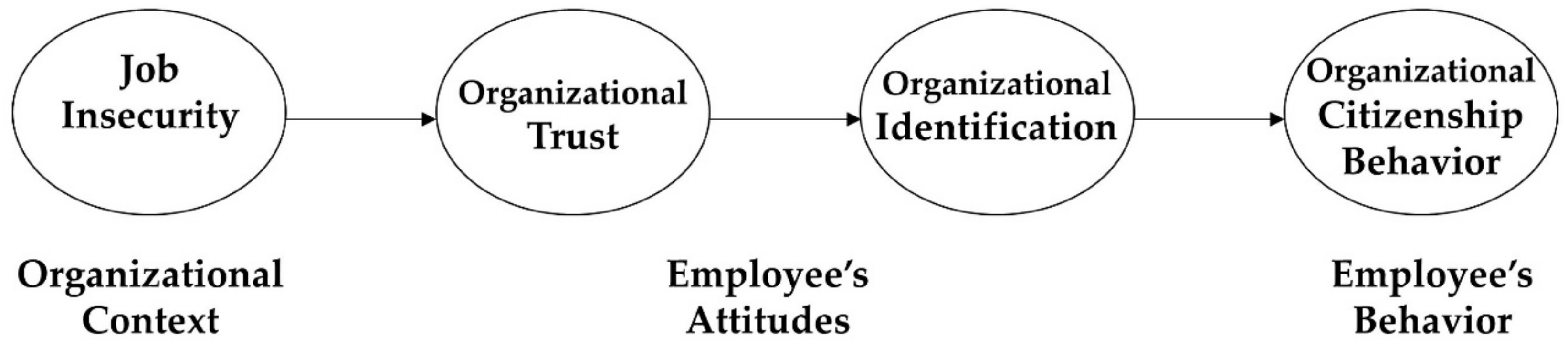

Unstable Jobs Cannot Cultivate Good Organizational Citizens: The Sequential Mediating Role of Organizational Trust and Identification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theories and Hypotheses

2.1. Job Insecurity and Organizational Trust

2.2. Organizational Trust and Organizational Identification

2.3. Organizational Identification and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

2.4. Sequential Mediating Role of Organizational Trust and Organizational Identification between Job Insecurity and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Job Insecurity (Time Point 1, Gathered from Employees)

3.2.2. Organizational trust (Time Point 2, Gathered from Employees)

3.2.3. Organizational Identification (Time point 3, Gathered from Employees)

3.2.4. Organizational Citizenship Behavior (Time Point 3, Gathered from an Immediate Leader of Each Employee)

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model

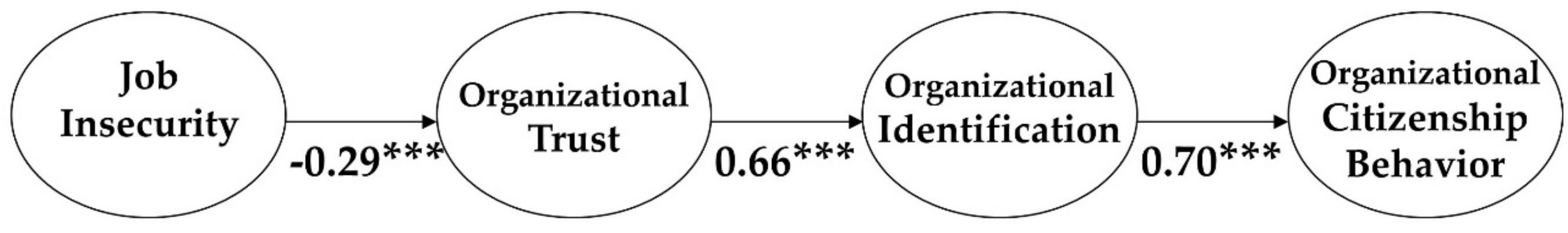

4.3. Structural Model

4.4. Bootstrapping

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lam, C.F.; Liang, J.; Ashford, S.; Lee, C. Job insecurity and organizational citizenship behavior: Exploring curvilinear and moderated relationships. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sverke, M.; Hellgren, J.; Näswall, K. No security: A meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 242–264. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Lu, C.; Siu, O. Job insecurity and job performance: The moderating role of organizational justice and the mediating role of work engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hui, C.; Lee, C. Moderating effects of organization-based self-esteem on organizational uncertainty: Employee response relationships. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 215–232. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G.H.-L.; Chan, D.K.-S. Who suffers more from job insecurity? A meta-analytic review. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 272–303. [Google Scholar]

- De Witte, H.; Pienaar, J.; De Cuyper, N. Review of 30 years of longitudinal studies on the association between job insecurity and health and well-being: Is there causal evidence? Aust. Psychol. 2016, 51, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrie, J.; Shipley, M.; Marmot, M.; Martikainen, P.; Stansfeld, S.; Smith, G. Job insecurity in white-collar workers: Toward an explanation of association with health. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gilboa, S.; Shirom, A.; Fried, Y.; Cooper, C. A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: Examining main and moderating effects. Pers. Psychol. 2008, 61, 227–271. [Google Scholar]

- Niessen, C.; Jimmieson, N.L. Threat of resource loss: The role of self-regulation in adaptive task performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Probst, T.M.; Stewart, S.M.; Gruys, M.L.; Tierney, B.W. Productivity, counterproductivity and creativity: The ups and downs of job insecurity. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2007, 80, 479–497. [Google Scholar]

- Shoss, M.K. Job insecurity: An integrative review and agenda for future research. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1911–1939. [Google Scholar]

- De Witte, H. Job insecurity and psychological well-being: Review of the literature and exploration of some unresolved issues. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1999, 8, 155–177. [Google Scholar]

- De Cuyper, N.; De Witte, H. The impact of job insecurity and contract type on attitudes, well-being and behavioural reports: A psychological contract perspective. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2006, 79, 395–409. [Google Scholar]

- Piccoli, B.; De Witte, H. Job insecurity and emotional exhaustion: Testing psychological contract breach versus distributive injustice as indicators of lack of reciprocity. Work Stress 2015, 29, 246–263. [Google Scholar]

- Loi, R.; Ngo, H.Y.; Zhang, L.Q.; Lau, V.P. The interaction between leader-member exchange and perceived job security in predicting employee altruism and work performance. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 669–685. [Google Scholar]

- Staufenbiel, T.; König, C.J. A model for the effects of job insecurity on performance, turnover intention, and absenteeism. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Stynen, D.; Forrier, A.; Sels, L.; De Witte, H. The relationship between qualitative job insecurity and OCB: Differences across age groups. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2015, 36, 383–405. [Google Scholar]

- Reisel, W.D.; Probst, T.M.; Chia, S.L.; Maloles, C.M.; König, C.J. The effects of job insecurity on job satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior, deviant behavior, and negative emotions of employees. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2010, 40, 74–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, J.K.; Brotheridge, C.M. Exploring the predictors and consequences of job insecurity’s components. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 40–64. [Google Scholar]

- Staufenbiel, T.; König, C.J. An evaluation of Borg’s cognitive and affective job insecurity scales. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.Q.; Wang, H.J.; Lu, J.J.; Du, D.Y.; Bakker, A.B. Does work engagement increase person-job fit? The role of job crafting and job insecurity. J. Voc. Behav. 2014, 84, 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- Vander Elst, T.; Näswall, K.; Bernhard-Oettel, C.; De Witte, H.; Sverke, M. The effect of job insecurity on employee health complaints: A within-person analysis of the explanatory role of threats to the manifest and latent benefits of work. J. Occup. Health. Psychol. 2016, 21, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books/D. C. Heath and Com: Lexington, KY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Borman, W.C.; Motowidlo, S.J. Task Performance and Contextual Performance: The Meaning for Personnel Selection Research. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; LePine, J.A. Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 909. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dirks, K.T.; Ferrin, D.L. The role of trust in organizational settings. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12, 450–467. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Sitkin, S.B.; Burt, R.S.; Camerer, C. Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 393–404. [Google Scholar]

- Whitener, E.M.; Brodt, S.E.; Korsgaard, M.A.; Werner, J.M. Managers as Initiators of Trust: An Exchange Relationship Framework for Understanding Managerial Trustworthy Behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 513–530. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M. In whom we trust: Group membership as an affective context for trust development. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 377–396. [Google Scholar]

- Ashford, S.J.; Lee, C.; Bobko, P. Content, cause, and consequences of job insecurity: A theory based measure and substantive test. Acad. Manag. J. 1989, 32, 803–829. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.L.; Branzyicki, I.; Bakasci, G. Person based reward systems: A theory of organizational reward practices in reform-communist organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 1994, 15, 261–282. [Google Scholar]

- Aryee, S.; Budhwar, P.S.; Chen, Z.X. Trust as a Mediator of the Relationship between Organizational Justice and Work Outcomes: Test of a Social Exchange Model. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 267–285. [Google Scholar]

- Salamon, S.D.; Robinson, S.L. Trust that binds: The impact of collective felt trust on organizational performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Settoon, R.P.; Bennett, N.; Liden, R.C. Social exchange in organizations: Perceived organizational support, leader-member exchange, and employee reciprocity. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; van Dick, R.; Tavares, S. Social identity and social exchange: Identification, support, and withdrawal from the job. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 457–477. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M.; Harquail, C.V. Organizational images and member identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, S.; Butcher, D. Trust in managerial relationships. J. Manag. Psychol. 2003, 18, 282–304. [Google Scholar]

- Ertürk, A. Exploring Predictors of Organizational Identification: Moderating Role of Trust on the Associations between Empowerment, Organizational Support, and Identification. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2010, 19, 409–441. [Google Scholar]

- Christ, O.; van Dick, R.; Wagner, U.; Stellmacher, J. When teachers go the extra mile: Foci of organisational identification as determinants of different forms of organisational citizenship behavior among schoolteachers. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 73, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dukerich, J.M.; Golden, B.R.; Shortell, S.M. Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder: The Impact of Organizational Identification, Identity, and Image on the Cooperative Behaviors of Physicians. Adm. Sci. Q. 2002, 47, 507–533. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dick, R.; Grojean, M.W.; Christ, O.; Wieseke, J. Identity and the extra mile: Relationships between organizational identification and organizational citizenship behaviour. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 283–301. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, K.D.; Cullen, J.B. Continuities and Extensions of Ethical Climate Theory: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Y.; Sung, S.Y.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.S. Top Management Ethical Leadership and Firm Performance: Mediating Role of Ethical and Procedural Justice Climate. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate Social Responsibility: Evolution of a Definitional Construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. A commentary and an overview of key questions on corporate social performance measurements. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 466–478. [Google Scholar]

- Mael, F.A.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, R.M.; Brewer, M.B. Effects of group identity on resource use in a simulated commons dilemma. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 1044–1057. [Google Scholar]

- Wan-Huggins, V.N.; Riordan, C.M.; Griffeth, R.W. The development and longitudinal test of a model of organizational identification. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 724–749. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, D.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Its Nature, Antecedents, and Consequences; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B. Impact of Organizational Citizenship Behavior on Organizational Performance: A Review and Suggestion for Future Research. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Hui, C. Organizational citizenship behaviors and managerial evaluations of employee performance: A review and suggestions for future research. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Ferris, G.R., Rowland, K.M., Eds.; JAI Press Inc.: Greenwich, UK, 1993; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; Whiting, S.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Blume, B.D. Individual- and Organizational-Level Consequences of Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Paine, J.B.; Bachrach, D.G. Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Critical Review of the Theoretical and Empirical Literature and Suggestions for Future Research. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 513–563. [Google Scholar]

- Kraimer, M.L.; Wayne, S.J.; Liden, R.C.; Sparrowe, R.T. The role of job security in understanding the relationship between employees’ perceptions of temporary workers and employees’ performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cook, J.; Wall, T. New work attitude measures of trust, organizational commitment and personal need non-fulfilment. J. Occup. Psychol. 1980, 53, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P.E.; Bauer, J.A.; Fox, S. Measurement Artifacts in the Assessment of Counterproductive Work Behavior and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Do we Know what we Think we Know? J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.E.; Joshi, A.; Erhardt, N.L. Recent Research on Team and Organizational Diversity: SWOT Analysis and Implications. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 801–830. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.G.; Smith, K.A.; Olian, J.D.; Sims, H.P.; O’Bannon, D.P.; Scully, J.A. Top Management Team Demography and Process: The Role of Social Integration and Communication. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 412–438. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G.W.; Lau, R.S. Testing Mediation and Suppression Effects of Latent Variables: Bootstrapping with Structural Equation Models. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 296–325. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sage Focus Ed. 1993, 154, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway, E.K. Using LISREL for Structural Equation Modeling: A Researcher’s Guide; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in Experimental and Nonexperimental Studies: New Procedures and Recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Percent |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 47.2% |

| Female | 52.8% |

| Age | |

| 20s | 21.8% |

| 30s | 24.1% |

| 40s | 27.0% |

| 50s | 27.1% |

| Occupation | |

| Office workers | 64.0% |

| Administrative positions | 19.5% |

| Sales and marketing | 6.6% |

| Manufacturing worker | 4.3% |

| Education | 1.3% |

| Position | |

| Staff | 29.0% |

| Assistant manager | 25.1% |

| Manager or deputy general manager | 30.4% |

| Department/general manager and above director | 15.5% |

| Tenure (in month) | |

| Below 50 | 51.8% |

| 50 to 100 | 19.1% |

| 100 to 150 | 14.6% |

| 150 to 200 | 5.2% |

| 200 to 250 | 4.3% |

| Above 250 | 5.0% |

| Firm size | |

| Above 500 members | 17.5% |

| 300–499 members | 5.6% |

| 100–299 members | 16.8% |

| 50–99 members | 13.5% |

| Below 50 members | 46.5% |

| Industry Type | |

| Manufacturing | 26.1% |

| Services | 14.9% |

| Construction | 13.5% |

| Information service and telecommunications | 9.9% |

| Education | 10.0% |

| Health and welfare | 8.3% |

| Public service and administration | 7.3% |

| Financial/insurance | 4.0% |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender_T2 | 1.53 | 0.50 | - | ||||||

| 2. Position_T2 | 2.56 | 1.39 | −0.36 ** | - | |||||

| 3. Tenure (Months)_T2 | 78.04 | 79.00 | −0.12 * | 0.32 ** | - | ||||

| 4. Education_T2 | 2.58 | 0.81 | −0.07 | 0.16 ** | 0.01 | - | |||

| 5. Job insecurity_T1 | 3.12 | 0.80 | −0.03 | 0.07 | -0.07 | 0.11 | - | ||

| 6. OT_T2 | 3.01 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 0.13 * | 0.11 | −0.10 | −0.29 ** | - | |

| 7. OI _T3 | 3.34 | 0.66 | 0.04 | 0.22 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.04 | −0.17 ** | 0.57 ** | - |

| 8. OCB_T3 | 3.15 | 0.69 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.12 * | −0.03 | −0.18 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.58 ** |

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | Δdf | Δχ2 | Preference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Factor Model | 859.02 | 52 | 0.641 | 0.544 | 0.227 | |||

| 2-Factor Model that integrates organizational trust and identification | 353.92 | 51 | 0.865 | 0.826 | 0.140 | 1 | 505.10 | 2-Factor Model |

| 3-Factor Model | 101.37 | 49 | 0.977 | 0.969 | 0.059 | 2 | 252.55 | 3-Factor Model |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, B.-J. Unstable Jobs Cannot Cultivate Good Organizational Citizens: The Sequential Mediating Role of Organizational Trust and Identification. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071102

Kim B-J. Unstable Jobs Cannot Cultivate Good Organizational Citizens: The Sequential Mediating Role of Organizational Trust and Identification. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(7):1102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071102

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Byung-Jik. 2019. "Unstable Jobs Cannot Cultivate Good Organizational Citizens: The Sequential Mediating Role of Organizational Trust and Identification" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 7: 1102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071102

APA StyleKim, B.-J. (2019). Unstable Jobs Cannot Cultivate Good Organizational Citizens: The Sequential Mediating Role of Organizational Trust and Identification. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071102