Gender Identity: The Human Right of Depathologization

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Depathologization Perspectives

3. Historical Precedent: Depathologization of Homosexuality or Sexual Diversity

4. Current Moment: Depathologization of Transgenderism or Gender Diversity

4.1. Depathologization as a Healthcare Issue

4.2. Evolution of the Diagnostic Classification in the ICD and the DSM

4.3. Depathologization as a Human Right Issue

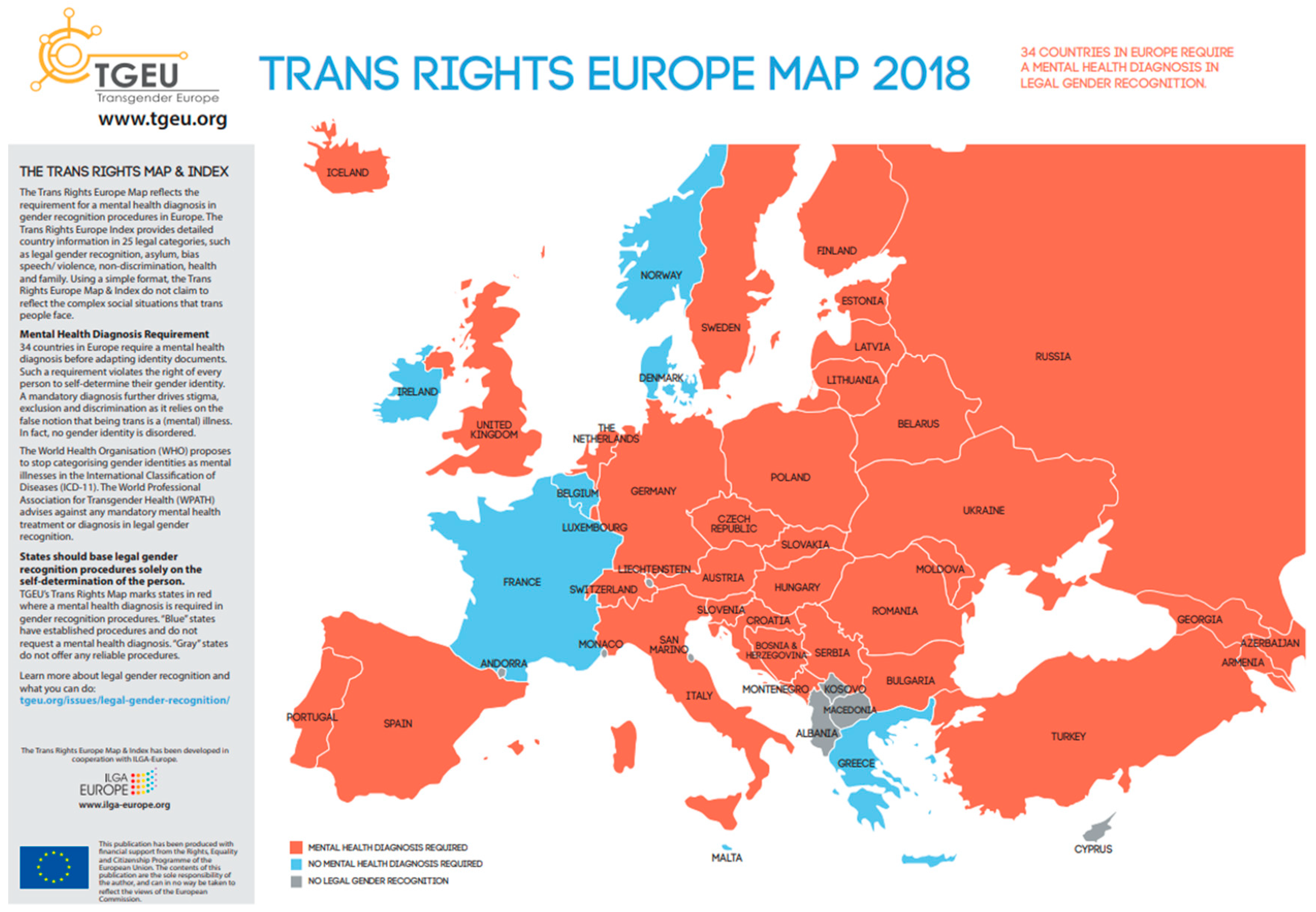

4.4. Depathologization as a Legal Issue

5. Uncertain Future: Depathologization of Intersexuality or Body Diversity

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DSM | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| ECHR | European Convection on Human Rights |

| GATE | Global Action for Trans Equality |

| ICD | International Classification Of Diseases |

| ILGA | The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association |

| SOC-7 | Standards of Care 7th Edition |

| STP | Stop Trans Pathologization |

| TGEU | Transgender Europe |

| TvT | Transrespect-versus-Transphobia Worldwide |

| UN | United Nations |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WPATH | World Professional Association for Transgender Health |

References

- FRA European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Being Trans in the European Union: Comparative Analysis of EU LGBT Survey Data; FRA European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights: Vienna, Austria, 2014; 129p. [Google Scholar]

- The Yogyakarta, Principles. Principles on the Application of International Human Rights Law in Relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity. 2018. Available online: http://yogyakartaprinciples.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/principles_en.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- The Yogyakarta, 10 Principles Plus. Additional Principles and State Obligations on the Application of International Human Rights Law in Relation to Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics to Complement the Yogyakarta Principles. 2017. Available online: http://yogyakartaprinciples.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/A5_yogyakartaWEB-2.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- Jones, T. Trump, trans students and transnational progress. Sex Educ. 2018, 18, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, S. Gender is Not Illness. How Pathologizing Trans People Violates International Human Rights Law; GATE: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Universal Declaration of Human Rights; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 1948; pp. 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Constitution of the World Health Organization. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2018).

- Davy, Z.; Sørlie, A.; Schwend, A.S. Democratising diagnoses? The role of the depathologisation perspective in constructing corporeal trans citizenship. Crit. Soc. Policy 2018, 38, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Emilio, J. Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1998; 269p. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Pérez, P.; Ortiz-Gómez, T.; Gil-García, E. La producción científica biomédica sobre transexualidad en España: Análisis bibliométrico y de contenido (1973–2011). Gac. Sanit. 2015, 29, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stop Trans Pathologization. International Campaign Stop Trans Pathologization. 2012. Available online: http://stp2012.info/old/en (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- GATE. Working on Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Bodily Diversity. 2018. Available online: https://transactivists.org/ (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- ILGA. The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 2018. Available online: https://www.ilga.org/ (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- TGEU. Transrespect vs Transphobia Worldwide. 2018. Available online: https://transrespect.org/en/ (accessed on 18 November 2018).

- Suess, A. Transitar por los Géneros es un Derecho: Recorridos por la Perspectiva de Despatologización. Granada. 2016. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=55894 (accessed on 27 November 2018).

- WPATH. World Professional Association for Transgender Health. 2018. Available online: https://www.wpath.org/ (accessed on 29 November 2018).

- WPATH. Standards of Care Version 7. 2018. Available online: https://www.wpath.org/publications/soc (accessed on 27 November 2018).

- World Health Organisation. ICD-10 Version:2016. 2016. Available online: http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5; American Psychiatricl Association: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; 947p. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. CD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. 2018. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3A%2F%2Fid.who.int%2Ficd%2Fentity%2F577470983 (accessed on 18 November 2018).

- Cooper, J. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edn, text revision) (DSM–IV–TR). Br. J. Psychiatry 2001, 176, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- yogyakartaprinciples.org. About the Yogyakarta Principles. 2018. Available online: http://yogyakartaprinciples.org/principles-en/about-the-yogyakarta-principles/ (accessed on 17 November 2018).

- European Courts of Human Rights. European Convention on Human Rights. 2018. Available online: https://www.echr.coe.int/Pages/home.aspx?p=basictexts&c (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Theilen, J.T. Depathologisation of transgenderism and international human rights law. Hum. Rights Law Rev. 2014, 14, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International A. Because of Who I Am. 2013. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/12000/eur010142013en.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2018).

- TGEU. Transgender Europe. Available online: https://tgeu.org/ (accessed on 18 November 2018).

- Dickens, B.M. Management of intersex newborns: Legal and ethical developments. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 143, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.; Jones, T.; Ward, R.; Dixon, J.; Mitchell, A.; Hillier, L. From Blues to Rainbows: The Mental Health and Well-Being of Gender Diverse and Transgender Young People in Australia. 2014. Available online: http://arrow.latrobe.edu.au:8080/vital/access/manager/Repository/latrobe:42299 (accessed on 12 November 2018).

- Carpenter, M. Intersex human rights: Clinical self-regulation has failed. Reprod. Health Matters. 2018. Available online: http://www.srhm.org/news/intersex-human-rights-clinical-self-regulation-has-failed/ (accessed on 20 November 2018).

- Carpenter, M. The human rights of intersex people: Addressing harmful practices and rhetoric of change. Reprod. Health Matters 2016, 24, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parliament European. European Parliament Resolution on the Rights of Intersex People. 2018. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/B-8-2019-0101_EN.html (accessed on 8 March 2019).

| DSM IV-TR (2001) [21] DSM IV (1994) | 11. Sexual and gender identity disorders | Sexual dysfunctions Paraphilias Gender Identity Disorders (GID) | F.64.2 GID in children F.64.0 GID in adolescents or adults F.64.9 GID not otherwise specified (intersex, cross-dressing behaviour) |

| DSM V (2013) [19] | Sexual Dysfunctions Gender Dysphoria (GD) | F.64.2 GD in children F.64.0 GD in adolescents or adults F.64.8 GD not otherwise specified | |

| ICD 10 (2016) [18] | 5. Mental and behavioural disorders | Disorders of adult personality and behaviour | F.64 Gender identity disorders F.66 Psychological and behavioural disorders associated with sexual development and orientation |

| ICD 11 (2018) [20] | 17. Conditions related to sexual health | Sexual dysfunctions Gender incongruence (GI) | HA60. GI of adolescence and adulthood HA61. GI in childhood 5A71. Adrogenital disorders |

| 20 Developmental anomalies | Malformative disorders of sex development | pseudohermaphroditism | |

| 24. Factors influencing health status and contact with health services | Gender incongruence |

| Principle 3: The Right to recognition before the law (without requirements such as hormone therapy, sterilization or surgery. All of these infringe upon human rights *) Principle 17: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health Principle 18: Protection from Medical Abuses Principle 31 (YP+10): The Right to Legal Recognition Principle 32 (YP+10): The Right to Bodily and Mental Integrity Principio 37 (YP+10): The Right to Truth |

| Country | Change of Name | Change of Gender | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Pathol. Requirement | Sterilization /Surgery Requirement | No | Yes | Pathol. Requirement | Sterilization/Surgery Requirement | No | Keeping Marriage Possible /Divorce necessary | More Than Two Gender Option | |

| Argentina (2012) * | x | x | No data | two | ||||||

| Australia | x | x | marriage | three | ||||||

| Belgium | x | x | x | x | divorce | two | ||||

| Bulgaria | x | x | divorce | two | ||||||

| Botswana | x (different) | x (different) | x | No data | two | |||||

| Chile | x | x | ||||||||

| China | x | x | x | x | divorce | two | ||||

| Colombia | x | x | x | divorce | two | |||||

| Cuba | x | x | x | x | divorce | two | ||||

| Germany | x | x | divorce | two | ||||||

| Denmark (2014) * | x | x | marriage | two | ||||||

| Egypt | x | x | ||||||||

| Georgia | x | x | x | divorce | two | |||||

| Greece | x | x | x | x | divorce | two | ||||

| Spain | x | x | x | x | marriage | two | ||||

| Finland | x | x | x | divorce | two | |||||

| France | x | x | x | x | divorce | two | ||||

| Croatia | x | x | divorce | two | ||||||

| India | x | x | divorce | three | ||||||

| Iceland | x | x | x | x | marriage | two | ||||

| Ireland (2015)* | x | x | two | |||||||

| Italy | x | x | x | x | divorce | two | ||||

| Japan | x | x | x | divorce | Two | |||||

| Kenia | x | x | ||||||||

| South Korea | x | x | x | No data | two | |||||

| Malta (2015)* | x | x | marriage | three | ||||||

| Mexico | x | x | x | x | marriage | two | ||||

| Netherlands | x | x | marriage | two | ||||||

| Norway | x | x | x | marriage | two | |||||

| Nepal | x | x | No data | three | ||||||

| New Zealand | x | x | marriage | three | ||||||

| Portugal | x | x | marriage | two | ||||||

| Romania | x | x | x | divorce | two | |||||

| Russia | x | x | marriage | two | ||||||

| Sweden | x | x | marriage | two | ||||||

| Singapore | x | x | x | x | divorce | two | ||||

| Switzerland | x | x | x | x | marriage | two | ||||

| United Kingdom | x | x | divorce | two | ||||||

| United States | x | x | x (some parts) | x (some parts) | marriage | two | ||||

| Venezuela | x | x | ||||||||

| South Africa | x | x | No data | two | ||||||

| Taiwan | x | x | x | marriage | two | |||||

| Turkey | x | x | x | divorce | two | |||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castro-Peraza, M.E.; García-Acosta, J.M.; Delgado, N.; Perdomo-Hernández, A.M.; Sosa-Alvarez, M.I.; Llabrés-Solé, R.; Lorenzo-Rocha, N.D. Gender Identity: The Human Right of Depathologization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 978. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060978

Castro-Peraza ME, García-Acosta JM, Delgado N, Perdomo-Hernández AM, Sosa-Alvarez MI, Llabrés-Solé R, Lorenzo-Rocha ND. Gender Identity: The Human Right of Depathologization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(6):978. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060978

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastro-Peraza, Maria Elisa, Jesús Manuel García-Acosta, Naira Delgado, Ana María Perdomo-Hernández, Maria Inmaculada Sosa-Alvarez, Rosa Llabrés-Solé, and Nieves Doria Lorenzo-Rocha. 2019. "Gender Identity: The Human Right of Depathologization" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 6: 978. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060978

APA StyleCastro-Peraza, M. E., García-Acosta, J. M., Delgado, N., Perdomo-Hernández, A. M., Sosa-Alvarez, M. I., Llabrés-Solé, R., & Lorenzo-Rocha, N. D. (2019). Gender Identity: The Human Right of Depathologization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), 978. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060978