Rates of Chronic Medical Conditions in 1991 Gulf War Veterans Compared to the General Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Self-Report of Medical Conditions

2.3. Self-Report of Exposures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

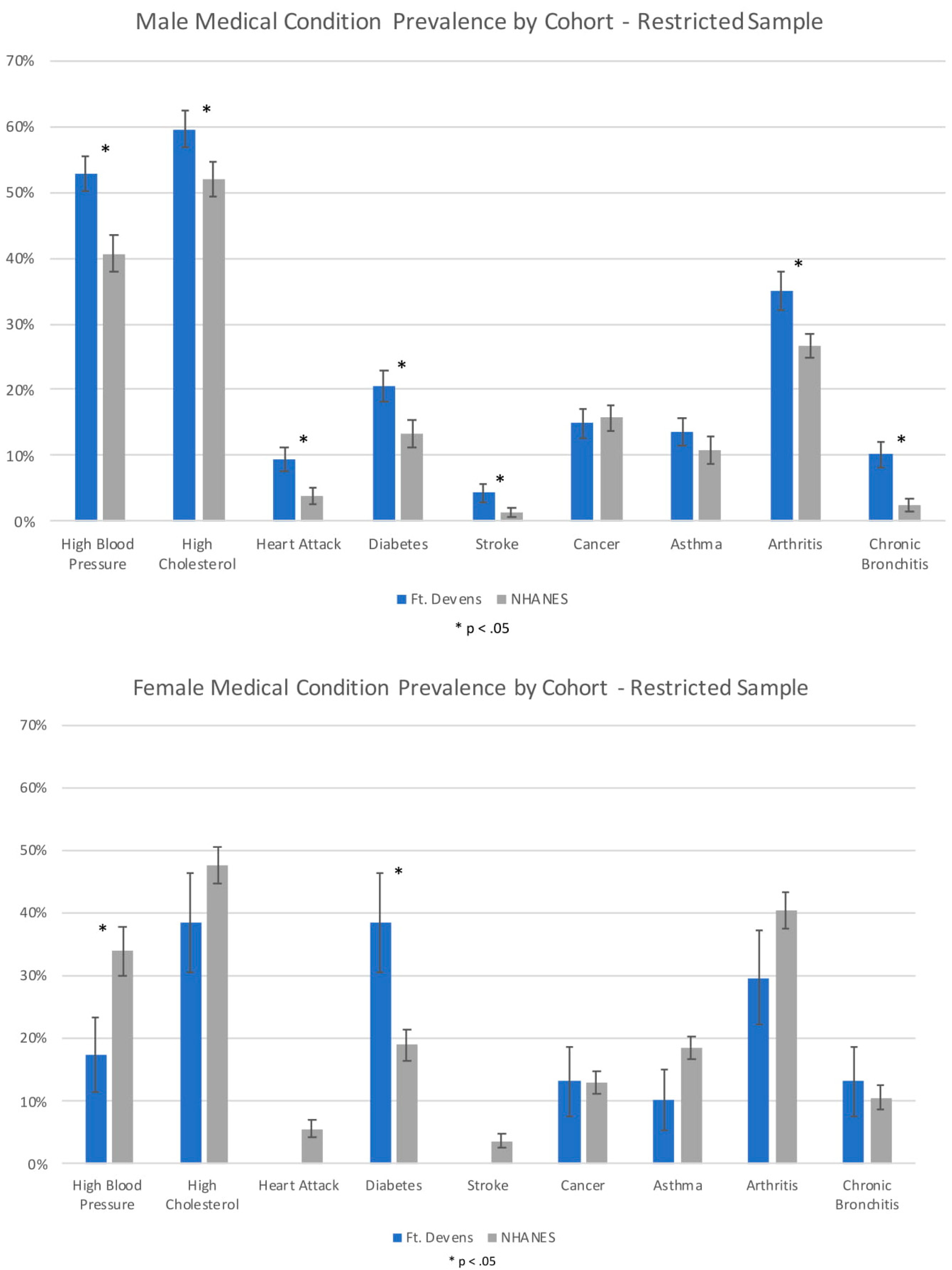

3.2. Chronic Conditions in the FDC and NHANES Cohort

3.3. Age and Gender Comparisons in FDC and NHANES Cohorts

3.4. Chronic Conditions and Toxicant Exposures in the Ft. Devens Cohort

3.5. Direct Comparison of Prevalence of Chronic Conditions in Men and Women within the Ft. Devens Cohort

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steele, L. Prevalence and Patterns of Gulf War Illness in Kansas Veterans: Association of Symptoms and Characteristics of Person, Place, and Time of Military Service. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 152, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, K.; Nisenbaum, R.; Stewart, G.; Thompson, W.; Robin, L.; Washko, R.; Noah, D.; Barrett, D.; Randall, B.; Herwaldt, B.; et al. Chronic Multisymptom Illness Affecting Air Force Veterans of the Gulf War. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1998, 280, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veteran’s Illnesses. Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans: Research Update and Recommenations, 2009–2013; 2014 Updated Scientific Findings and Recommendations; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- Maule, A.L.; Janulewicz, P.A.; Sullivan, K.A.; Krengel, M.H.; Yee, M.K.; McClean, M.; White, R.F. Meta-analysis of self-reported health symptoms in 1990–1991 Gulf War and Gulf War-era veterans. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e016086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, R.F.; Steele, L.; O’Callaghan, J.P.; Sullivan, K.; Binns, J.H.; Golomb, B.A.; Bloom, F.E.; Bunker, J.A.; Crawford, F.; Graves, J.C.; et al. Recent research on Gulf War illness and other health problems in veterans of the 1991 Gulf War: Effects of toxicant exposures during deployment. Cortex 2016, 74, 449–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, K.; Krengel, M.; Proctor, S.P.; Devine, S.; Heeren, T.; White, R.F. Cognitive Functioning in Treatment-Seeking Gulf War Veterans: Pyridostigmine Bromide Use and PTSD. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2003, 25, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, K.; Krengel, M.; Bradford, W.; Stone, C.; Thompson, T.A.; Heeren, T.; White, R.F. Neuropsychological functioning in military pesticide applicators from the Gulf War: Effects on information processing speed, attention and visual memory. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2018, 65, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golomb, B.A. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and Gulf War illnesses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 4295–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.K.; Li, B.; Mahan, C.M.; Eisen, S.A.; Engel, C.C. Health of US veterans of 1991 Gulf War: A follow-up survey in 10 years. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009, 51, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, K.; Kent, K.; Sherwood, R.; Hull, L.; Seed, P.; David, A.S.; Wessely, S. Chronic fatigue syndrome and related disorders in UK veterans of the Gulf War 1990–1991: Results from a two-phase cohort study. Psychol. Med. 2008, 38, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, B.; Long, K.; Rull, R.P.; Dursa, E.K.; Millennium Cohort Study Team. Health Status of Gulf War and Era Veterans Serving in the US Military in 2000. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, e261–e267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unwin, C.; Blatchley, N.; Coker, W.; Ferry, S.; Hotopf, M.; Hull, L.; Ismail, K.; Palmer, I.; David, A.; Wessely, S. Health of UK servicemen who served in Persian Gulf War. Lancet 1999, 353, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, G.C.; Reed, R.J.; Kaiser, K.S.; Smith, T.C.; Gastañaga, V.M. Self-reported Symptoms and Medical Conditions among 11,868 Gulf War-era Veterans. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 155, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Mahan, C.M.; Kang, H.K.; Eisen, S.A.; Engel, C.C. Longitudinal health study of US 1991 Gulf War veterans: Changes in health status at 10-year follow-up. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 174, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haley, R.W. Excess Incidence of ALS in young Gulf War veterans. Am. Acad. Neurol. 2003, 61, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, R.D.; Kamins, K.G.; Feussner, J.R.; Grambow, S.C.; Hoff-Lindquist, J.; Harati, Y.; Mitsumoto, H.; Pascuzzi, R.; Spencer, P.S.; Tim, R.; et al. Occurrence of amyotrophic lateral scelrosis among Gulf War veterans. Am. Acad. Neurol. 2003, 61, 742–749. [Google Scholar]

- Horner, R.D.; Grambow, S.C.; Coffman, C.J.; Lindquist, J.H.; Oddone, E.Z.; Allen, K.D.; Kasarskis, E.J. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis among 1991 Gulf War veterans: Evidence for a time-limited outbreak. Neuroepidemiology 2008, 31, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, H.A.; Maillard, J.D.; Levine, P.H.; Simmens, S.J.; Mahan, C.M.; Kang, H.K. Investigating the risk of cancer in 1990–1991 US Gulf War veterans with the use of state cancer registry data. Ann. Epidemiol. 2010, 20, 265.e1–272.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullman, T.A.; Mahan, C.M.; Kang, H.K.; Page, W.F. Mortality in US Army Gulf War veterans exposed to 1991 Khamisiyah chemical munitions destruction. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 1382–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, S.K.; Kang, H.K.; Bullman, T.A.; Wallin, M.T. Neurological mortality among U.S. veterans of the Persian Gulf War: 13-year follow-up. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2009, 52, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCauley, L.A.; Lasarev, M.; Sticker, M.; Rischitelli, G.; Spencer, P.S. Illness Experience of Gulf War Veterans Possibly Exposed to Chemical Warfare Agents. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 23, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.K.; Mahan, C.M.; Lee, K.Y.; Magee, C.A.; Murphy, F.M. Illnesses Among United States Veterans of the Gulf War: A Population-Based Survey of 30,000 Veterans. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2000, 42, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelsall, H.L.; Sim, M.R.; Forbes, A.B.; Glass, D.C.; McKenzie, D.P.; Ikin, J.F.; Abramson, M.J.; Blizzard, L.; Ittak, P. Symptoms and medical conditions in Australian veterans of the 1991 Gulf War: Relation to immunisations and other Gulf War exposures. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 61, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, D.N.; Lange, J.L.; Heller, J.; Kirkpatrick, J.; DeBakey, S. A Case-Control Study of Asthma among U.S. Army Gulf War Veterans and Modeled Exposure to Oil Well Fire Smoke. Mil. Med. 2002, 167, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2014; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, J.; Proctor, S.P.; Erickson, D.J.; Hu, H. Risk Factors for Multisymptom Illness in US Army Veterans of the Gulf War. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2002, 44, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, S. Health status of Persian Gulf War veterans: Self-reported symptoms, environmental exposures and the effect of stress. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1998, 27, 1000–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krengel, M. Redefining Gulf War Illness Using Longitudinal Health Data: The Fort Devens Cohort Annual Report; W81XWH-11-1-0818; U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command: Fort Detrick, MD, USA, August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, S.; Zhu, B.P.; Black, W.; Brownson, R.C. A comparison of national estimates of obesity prevalence from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2006, 30, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, N.; Creed, F.; Silman, A.; Dunn, G.; Baxter, D.; Smedley, J.; Taylor, S.; Macfarlane, G.J. Health and exposures of United Kingdom Gulf war veterans. Part II: The relation of health to exposure. Occup. Environ. Med. 2001, 58, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.; Horvath, J. The Growing Burden of Chronic Disease in America. Public Health Rep. 2004, 119, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, S.S.; McNeil, R.B.; Provenzale, D.T.; Dursa, E.K.; Thomas, C.M. Method Issues in Epidemiological Studies of Medically Unexplained Symptom-based Conditions in Veterans. J. Mil. Veterans Health 2013, 21, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Smylie, A.L.; Broderick, G.; Fernandes, H.; Razdan, S.; Barnes, Z.; Collado, F.; Sol, C.; Fletcher, M.A.; Klimas, N. A comparison of sex-specific immune signatures in Gulf War illness and chronic fatigue syndrome. BMC Immunol. 2013, 14, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craddock, T.J.; Fritsch, P.; Rice, M.A., Jr.; del Rosario, R.M.; Miller, D.B.; Fletcher, M.A.; Klimas, N.G.; Broderick, G. A role for homeostatic drive in the perpetuation of complex chronic illness: Gulf War Illness and chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, K.J.; Palumbo, C.L.; Proctor, S.P.; Killiany, R.J.; Yurgelun-Todd, D.A.; White, R.F. Quantitative magnetic resonance brain imaging in US army veterans of the 1991 Gulf War potentially exposed to sarin and cyclosarin. Neurotoxicology 2007, 28, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, L.L.; Rothlind, J.C.; Cardenas, V.A.; Meyerhoff, D.J.; Weiner, M.W. Effects of low-level exposure to sarin and cyclosarin during the 1991 Gulf War on brain function and brain structure in US veterans. Neurotoxicology 2010, 31, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, L.L.; Abadjian, L.; Hlavin, J.; Meyerhoff, D.J.; Weiner, M.W. Effects of low-level sarin and cyclosarin exposure and Gulf War Illness on brain structure and function: A study at 4T. Neurotoxicology 2011, 32, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, S.P.; Heaton, K.J.; Heeren, T.; White, R.F. Effects of sarin and cyclosarin exposure during the 1991 Gulf War on neurobehavioral functioning in US army veterans. Neurotoxicology 2006, 27, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, L.; Sastre, A.; Gerkovich, M.M.; Cook, M.R. Complex factors in the etiology of Gulf War illness: Wartime exposures and risk factors in veteran subgroups. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golier, J.A.; Legge, J.; Yehuda, R. The ACTH response to dexamethasone in Persian Gulf War veterans. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1071, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, K.; Krengel, M.; Janulewicz, P.; Chamberlain, J. An overview of toxicant exposures in veterans cohorts from Vietnam to Iraq. In Military Medical Care: From Predeployment to Post-Separation; Routledge Publishers: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Koslik, H.J.; Hamilton, G.; Golomb, B.A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Gulf War illness revealed by 31Phosphorus Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy: A case-control study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, L.; Evans, J.E.; Joshi, U.; Crynen, G.; Reed, J.; Mouzon, B.; Baumann, S.; Montague, H.; Zakirova, Z.; Emmerich, T.; et al. Translational potential of long-term decreases in mitochondrial lipids in a mouse model of Gulf War Illness. Toxicology 2016, 372, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakirova, Z.; Reed, J.; Crynen, G.; Horne, L.; Hassan, S.; Mathura, V.; Mullan, M.; Crawford, F.; Ait-Ghezala, G. Complementary proteomic approaches reveal mitochondrial dysfunction, immune and inflammatory dysregulation in a mouse model of Gulf War Illness. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2017, 11, 1600190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.B.; Michalovicz, L.T.; Calderazzo, S.; Kelly, K.A.; Sullivan, K.; Killiany, R.J.; O’Callaghan, J.P. Corticosterone potentiates DFP-induced neuroinflammation and affects high-order diffusion imaging in a rat model of Gulf War Illness. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018, 67, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Ft. Devens (n = 448) Mean ± SD or N (%) | NHANES (n = 2959) Mean ± SD or N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age * | 53.93 ± 8.33 | 55.86 ± 10.23 |

| Male * | 54.13 ± 8.38 | 54.74 ± 9.04 |

| Female * | 52.15 ± 7.75 | 56.68 ± 10.90 |

| Sex * | ||

| Male | 401 (89.5) | 1249 (42.3) |

| Female | 47 (10.5) | 1710 (57.7) |

| Race/Ethnicity * | ||

| Black/African American | 12 (2.7) | 592 (10.4) |

| White/Caucasian | 416 (92.9) | 1189 (69.2) |

| Hispanic | 7 (1.6) | 731 (12.7) |

| Asian | 1 (0.2) | 389 (5.6) |

| Other/Multiracial | 10 (2.2) | 58 (1.9) |

| Missing | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

| Education * | ||

| Less than a high school diploma | 1 (0.2) | 762 (25.8) |

| High School Diploma | 80 (17.9) | 660 (22.3) |

| Other Training or Some College | 171 (38.2) | 803 (27.1) |

| College or Above | 195 (43.5) | 731 (24.7) |

| Missing | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) |

| Current Smoking * | ||

| Yes | 73 (16.3) | 588 (19.9) |

| No | 372 (83.0) | 2370 (80.1) |

| Missing | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.0) |

| Exposures | ||

| Self-reported Exposures | ||

| Chemical/Biological Warfare (CBW) | 178 (39.7) | |

| Missing CBW Data | 131 (29.2) | |

| Pyridostigmine Bromide (PB) pills | 247 (55.1) | |

| Missing PB Data | 89 (19.9) | |

| Prevalence of Gulf War Illness (GWI) | ||

| Fukuda Criteria | 265 (59.2) | |

| Male | 237 (59.1) | |

| Female | 28 (59.6) | |

| Fukuda—Severe Criteria | 58 (21.9) | |

| Male | 52 (21.9) | |

| Female | 6 (21.4) | |

| Kansas Criteria | 147 (32.8) | |

| Male | 132 (32.9) | |

| Female | 15 (31.9) | |

| Prevalence of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) | 26 (9.4) | |

| Male | 21 (8.7) | |

| Female | 5 (13.5) | |

| Prevalence of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) | 47 (16.4) | |

| Male | 38 (15.4) | |

| Female | 9 (23.1) | |

| Prevalence of Fibromyalgia | 11 (3.7) | |

| Male | 8 (3.1) | |

| Female | 3 (7.7) |

| Condition | Ft. Devens % (n = 401) | NHANES % (n = 1249) | Excess Prevalence [CI] | p-Value | OR [CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||||

| Self-reported doctor diagnosed medical conditions | |||||

| High Blood Pressure | 52.9% | 40.7% | 12.3% [6.5–18.1] | 0.000 | 1.64 [1.299–2.073] |

| High Cholesterol | 59.5% | 49.7% | 9.8% [3.8–15.9] | 0.001 | 1.49 [1.165–1.904] |

| Heart Attack | 9.2% | 4.7% | 4.5% [0.6–8.4] | 0.025 | 2.04 [1.093–3.805] |

| Diabetes | 20.9% | 15.5% | 5.4% [−0.03–10.8] | 0.051 | 1.44 [0.998–2.078] |

| Stroke | 4.4% | 2.3% | 2.1% [−0.6–4.7] | 0.133 | 1.93 [0.819–4.549] |

| Cancer | 14.4% | 12.3% | 2.1% [−2.7–6.9] | 0.391 | 1.20 [0.791–1.819] |

| Asthma | 15.3% | 10.4% | 4.9% [−0.07–9.9] | 0.053 | 1.56 [0.994–2.448] |

| Arthritis | 35.9% | 25.4% | 10.5% [4.5–16.6] | 0.001 | 1.65 [1.238–2.192] |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 10.7% | 2.6% | 8.0% [4.1–11.9] | 0.000 | 4.41 [2.138–9.078] |

| Women % (n = 47) % (n = 1710) | |||||

| Self-reported doctor diagnosed medical conditions | |||||

| High Blood Pressure | 22.2% | 46.8% | −24.6% [−37.3–(−11.8)] | 0.000 | 0.32 [0.181–0.582] |

| High Cholesterol | 37.2% | 45.5% | −8.3% [−23.1–6.5] | 0.271 | 0.71 [0.385–1.308] |

| Heart Attack | 2.5% | 4.5% | −2.0% [−7.0–3.1] | 0.440 | 0.55 [0.117–2.541] |

| Diabetes | 37.2% | 17.4% | 19.8% [5.1–34.4] | 0.008 | 2.81 [1.308–6.035] |

| Stroke | 0% | 4.1% | −4.1% [−5.1–(−3.1)] | N/A | N/A |

| Cancer | 12.2% | 12.8% | −0.6% [−10.8–9.5] | 0.904 | 0.94 [0.373–2.387] |

| Asthma | 9.5% | 18.1% | −8.6% [−17.8–0.6] | 0.067 | 0.48 [0.215–1.054] |

| Arthritis | 29.3% | 41.2% | −11.9% [−26.2–2.4] | 0.104 | 0.59 [0.314–1.113] |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 17.1% | 9.6% | 7.4% [−4.3–19.1] | 0.213 | 1.93 [0.686–5.424] |

| Men – Restricted Analyses | % (n = 372) | % (n = 373) | |||

| Self-reported doctor diagnosed medical conditions | |||||

| High Blood Pressure | 52.7% | 40.6% | 12.2% [4.7–19.6] | 0.001 | 1.63 [1.208–2.211] |

| High Cholesterol | 59.6% | 51.9% | 7.7% [0.2–15.2] | 0.044 | 1.37 [1.009–1.855] |

| Heart Attack | 9.4% | 3.8% | 5.6% [1.3–9.9] | 0.010 | 2.63 [1.255–5.530] |

| Diabetes | 20.5% | 13.4% | 7.1% [0.9–13.4] | 0.025 | 1.67 [1.066–2.620] |

| Stroke | 4.3% | 1.4% | 2.9% [0.1–5.6] | 0.041 | 3.19 [1.050–9.679] |

| Cancer | 14.9% | 15.7% | −0.8% [−6.6–5.0] | 0.782 | 0.94 [0.602–1.465] |

| Asthma | 13.6% | 10.9% | 2.7% [−3.1–8.6] | 0.362 | 1.29 [0.746–2.228] |

| Arthritis | 35.0% | 26.7% | 8.2% [1.5–15.0] | 0.017 | 1.47 [1.073–2.026] |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 10.2% | 2.5% | 7.7% [3.6–11.8] | 0.000 | 4.50 [2.017–10.029] |

| Women – Restricted Analyses | % (n = 42) | % (n = 639) | |||

| Self-reported doctor diagnosed medical conditions | |||||

| High Blood Pressure | 17.5% | 33.9% | −16.4% [−30.3–(−2.5)] | 0.021 | 0.41 [0.196–0.874] |

| High Cholesterol | 38.5% | 47.7% | −9.2% [−25.6–7.0] | 0.266 | 0.68 [0.351–1.334] |

| Heart Attack | 0% | 5.6% | −5.6% [−8.4–(−2.8)] | N/A | N/A |

| Diabetes | 38.5% | 19.0% | 19.5% [3.4–35.6] | 0.017 | 2.67 [1.189–6.001] |

| Stroke | 0% | 3.7% | −3.7% [−5.9–(−1.5)] | N/A | N/A |

| Cancer | 13.2% | 13.0% | 0.2% [−11.1–11.4] | 0.977 | 1.01 [0.377–2.733] |

| Asthma | 10.3% | 18.6% | −8.3% [−18.5–1.8] | 0.109 | 0.50 [0.215–1.166] |

| Arthritis | 29.7% | 40.4% | −10.6% [−26.4–5.1] | 0.187 | 0.63 [0.312–1.255] |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 13.2% | 10.6% | 2.5% [−8.9–14.0] | 0.663 | 1.28 [0.427–3.820] |

| Condition | Ft. Devens | NHANES | Excess Prevalence [CI] | p-Value | OR [CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40s | % (n = 142) | % (n = 387) | |||

| Self-reported doctor diagnosed medical conditions | |||||

| High Blood Pressure | 43.6% | 26.4% | 17.2% [7.9–26.5] | 0.000 | 2.16 [1.423–3.272] |

| High Cholesterol | 50.8% | 37.6% | 13.2% [3.3–23.1] | 0.009 | 1.71[1.144–2.561] |

| Heart Attack | 4.5% | 1.8% | 2.7% [−1.4–6.7] | 0.199 | 2.54 [0.612–10.509] |

| Diabetes | 14.2% | 9.3% | 4.9% [−2.2–12.0] | 0.174 | 1.62 [0.808–3.232] |

| Stroke | 0% | 0.8% | −0.8% [−1.6–0.01] | N/A | N/A |

| Cancer | 5.4% | 2.8% | 2.6% [−2.0–7.1] | 0.267 | 1.95 [0.599–6.373] |

| Asthma | 12.8% | 10.9% | 2.0% [−5.0–9.0] | 0.578 | 1.21 [0.618–2.373] |

| Arthritis | 17.0% | 12.2% | 4.8% [−3.1–12.7] | 0.231 | 1.48 [0.780–2.789] |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 4.7% | 1.8% | 2.9% [−1.4–7.1] | 0.183 | 2.66 [0.629–11.256] |

| 50s | % (n = 149) | % (n = 382) | |||

| High Blood Pressure | 55.1% | 40.8% | 14.3% [4.8–23.7] | 0.003 | 1.78 [1.215–2.602] |

| High Cholesterol | 61.3% | 45.8% | 15.5% [5.6–25.4] | 0.002 | 1.87 [1.253–2.805] |

| Heart Attack | 9.3% | 4.2% | 5.1% [−1.0–11.2] | 0.103 | 2.34 [0.842–6.503] |

| Diabetes | 20.0% | 15.2% | 4.8% [−3.7–13.3] | 0.270 | 1.39 [0.773–2.509] |

| Stroke | 2.1% | 2.6% | −0.5% [−3.8–2.7] | 0.746 | 0.79 [0.188–3.311] |

| Cancer | 17.6% | 6.5% | 11.1% [3.3–18.9] | 0.005 | 3.06 [1.393–6.723] |

| Asthma | 13.4% | 10.2% | 3.2% [−4.3–10.6] | 0.404 | 1.36 [0.662–2.782] |

| Arthritis | 43.8% | 22.0% | 21.8% [11.4–32.1] | 0.000 | 2.76 [1.700–4.471] |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 13.1% | 2.6% | 10.5% [3.7–17.4] | 0.003 | 5.62 [1.824–17.335] |

| 60s | % (n = 96) | % (n = 480) | |||

| High Blood Pressure | 67.4% | 58.6% | 8.8% [−1.6–19.2] | 0.098 | 1.46 [0.932–2.286] |

| High Cholesterol | 71.1% | 54.4% | 16.7% [5.9–27.4] | 0.002 | 2.06 [1.292–3.279] |

| Heart Attack | 20.3% | 10.2% | 10.1% [−0.5–20.8] | 0.062 | 2.25 [0.960–5.252] |

| Diabetes | 34.4% | 29.9% | 4.4% [−8.0–16.8] | 0.483 | 1.23 [0.694–2.166] |

| Stroke | 16.1% | 5.8% | 10.2% [0.4–20.1] | 0.042 | 3.08 [1.041–9.139] |

| Cancer | 27.6% | 15.2% | 12.4% [0.4–24.3] | 0.043 | 2.12 [1.026–4.398] |

| Asthma | 23.2% | 9.8% | 13.4% [2.0–24.8] | 0.021 | 2.79 [1.168–6.643] |

| Arthritis | 55.0% | 34.5% | 20.5% [7.2–33.8] | 0.003 | 2.32 [1.342–4.004] |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 15.1% | 3.8% | 11.3% [1.5–21.1] | 0.024 | 4.54 [1.226–16.837] |

| 40s – Restricted Analyses | % (n = 134) | % (n = 124) | |||

| High Blood Pressure | 42.4% | 29.0% | 13.4% [−0.2–27.0] | 0.054 | 1.80 [0.991–3.279] |

| High Cholesterol | 50.0% | 47.3% | 2.7% [−11.1–16.5] | 0.704 | 1.11 [0.641–1.933] |

| Heart Attack | 4.6% | 0.2% | 4.4% [0.5–8.4] | 0.029 | 27.36 [1.413–529.776] |

| Diabetes | 13.8% | 7.2% | 6.6% [−2.9–16.1] | 0.175 | 2.06 [0.725–5.867] |

| Stroke | 0% | 0% | 0% | N/A | N/A |

| Cancer | 5.6% | 6.7% | −1.2% [−8.0–5.7] | 0.741 | 0.82 [0.246–2.709] |

| Asthma | 11.4% | 11.0% | 0.4% [−7.9–8.7] | 0.918 | 1.04 [0.454–2.405] |

| Arthritis | 16.3% | 19.0% | −2.7% [−13.5–8.2] | 0.629 | 0.83 [0.394–1.757] |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 4.8% | 0.9% | 3.9% [−0.4–8.2] | 0.077 | 5.51 [0.829–36.651] |

| 50s – Restricted Analyses | % (n = 135) | % (n = 123) | |||

| High Blood Pressure | 56.4% | 43.1% | 13.3% [−2.7–29.4] | 0.104 | 1.71 [0.896–3.259] |

| High Cholesterol | 63.1% | 49.9% | 13.2% [−0.1–26.4] | 0.051 | 1.71 [0.997–2.947] |

| Heart Attack | 10.5% | 3.6% | 6.9% [−0.8–14.6] | 0.080 | 3.14 [0.871–11.340] |

| Diabetes | 20.2% | 14.4% | 5.9% [−5.1–16.8] | 0.295 | 1.51 [0.698–3.272] |

| Stroke | 2.4% | 1.7% | 0.7% [−3.3–4.7] | 0.732 | 1.43 [0.184–11.088] |

| Cancer | 18.7% | 17.0% | 1.7% [−10.4–13.8] | 0.788 | 1.12 [0.490–2.559] |

| Asthma | 11.6% | 10.2% | 1.4% [−7.6–10.5] | 0.755 | 1.16 [0.458–2.934] |

| Arthritis | 43.0% | 25.1% | 17.9% [5.9–29.9] | 0.004 | 2.25 [1.306–3.876] |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 12.5% | 3.5% | 9.0% [1.4–16.6] | 0.020 | 3.94 [1.242–12.507] |

| 60s+ - Restricted Analyses | % (n = 89) | % (n = 126) | |||

| High Blood Pressure | 67.0% | 54.2% | 12.9% [−1.5–27.2] | 0.079 | 1.72 [0.939–3.153] |

| High Cholesterol | 70.5% | 62.0% | 8.5% [−6.6–23.6] | 0.269 | 1.47 [0.744–2.892] |

| Heart Attack | 19.6% | 9.6% | 10.0% [−2.3–22.4] | 0.112 | 2.30 [0.824–6.441] |

| Diabetes | 32.8% | 21.4% | 11.4% [−2.2–25.0] | 0.100 | 1.79 [0.894–3.597] |

| Stroke | 15.1% | 3.0% | 12.1% [1.9–22.2] | 0.020 | 5.69 [1.313–24.695] |

| Cancer | 28.6% | 27.4% | 1.2% [−13.7–16.0] | 0.877 | 1.06 [0.507–2.215] |

| Asthma | 20.8% | 11.8% | 8.9% [−3.8–21.7] | 0.170 | 1.96 [0.750–5.101] |

| Arthritis | 55.4% | 40.7% | 14.6% [−0.9–30.2] | 0.065 | 1.80 [0.963–3.379] |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 13.7% | 3.2% | 10.5% [0.6–20.5] | 0.038 | 4.83 [1.092–22.359] |

| Condition | Exposed % (n = 178) | Unexposed % (n = 139) | Excess Prevalence | p-Value | OR [CI] | Adjusted OR [CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical/Biological Warfare (CBW) | ||||||

| Self reported doctor diagnosed medical conditions | ||||||

| High Blood Pressure | 54.0% | 42.0% | 12.0% | 0.040 | 1.621 [1.033–2.544] | 1.601 [1.012–2.533] |

| High Cholesterol | 56.8% | 53.4% | 3.4% | 0.633 | 1.145 [0.717–1.827] | 1.084 [0.674–1.742] |

| Heart Attack | 11.0% | 5.5% | 5.5% | 0.161 | 2.147 [0.796–5.795] | 2.013 [0.742–5.464] |

| Diabetes | 29.9% | 8.9% | 21.0% | 0.000 | 4.340 [2.055–9.165] | 3.242 [1.647–6.382] |

| Stroke | 4.1% | 3.7% | 0.4% | 1.000 | 1.122 [0.293–4.288] | 1.116 [0.289–4.310] |

| Cancer | 17.5% | 11.4% | 6.1% | 0.204 | 1.643 [0.785–3.439] | 1.494 [0.722–3.090] |

| Asthma | 18.5% | 10.3% | 8.2% | 0.094 | 1.987 [0.919–4.296] | 1.940 [0.896–4.201] |

| Arthritis | 43.4% | 23.9% | 19.5% | 0.002 | 2.446 [1.403–4.265] | 2.199 [1.261–3.834] |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 16.0% | 5.7% | 10.3% | 0.020 | 3.175 [1.225–8.229] | 3.997 [1.426–11.202] |

| Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) | 15.2% | 2.8% | 12.4% | 0.002 | 6.131 [1.717–21.889] | 5.957 [1.664–21.321] |

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) | 24.8% | 8.7% | 16.1% | 0.003 | 3.439 [1.529–7.734] | 3.401 [1.502–7.699] |

| Pyridostigmine Bromide (PB) Pills % (n = 247) % (n = 112) | ||||||

| Self reported doctor diagnosed medical conditions | ||||||

| High Blood Pressure | 50.2% | 40.9% | 9.3% | 0.109 | 1.456 [0.923–2.299] | 1.542 [0.969–2.453] |

| High Cholesterol | 58.4% | 51.0% | 7.4% | 0.226 | 1.351 [0.840–2.174] | 1.305 [0.807–2.110] |

| Heart Attack | 11.5% | 1.1% | 10.4% | 0.003 | 11.348 [1.501–85.798] | 12.141 [1.601–92.054] |

| Diabetes | 23.7% | 11.2% | 12.5% | 0.015 | 2.452 [1.172–5.128] | 2.175 [1.107–4.273] |

| Stroke | 4.6% | 1.1% | 3.5% | 0.280 | 4.193 [0.516–34.067] | 4.673 [0.572–38.192] |

| Cancer | 15.3% | 10.1% | 5.2% | 0.265 | 1.606 [0.723–3.567] | 1.443 [0.666–3.124] |

| Asthma | 12.5% | 11.5% | 1.0% | 0.845 | 1.100 [0.496–2.438] | 1.127 [0.507–2.505] |

| Arthritis | 36.4% | 31.4% | 5.0% | 0.494 | 1.249 [0.725–2.152] | 1.223 [0.711–2.105] |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 13.1% | 8.0% | 5.1% | 0.227 | 1.751 [0.720–4.255] | 1.664 [0.678–4.085] |

| Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) | 10.9% | 2.4% | 8.5% | 0.037 | 4.885 [1.094–21.809] | 5.076 [1.132–22.760] |

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) | 20.9% | 8.6% | 12.3% | 0.017 | 2.791 [1.175–6.627] | 2.662 [1.112–6.372] |

| Medical Condition | Men | Women | p-Value | OR [CI] | * Adjusted OR [CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Blood Pressure | 52.9% | 22.2% | 0.000 | 3.933 [1.895–1.895] | 3.454 [1.622–7.353] |

| High Cholesterol | 59.5% | 37.2% | 0.006 | 2.484 [1.291–4.777] | 2.249 [1.127–4.488] |

| Heart Attack | 9.2% | 2.5% | 0.224 | 3.961 [0.523–30.024] | 3.253 [0.415–25.466] |

| Diabetes | 20.9% | 37.2% | 0.021 | 0.447 [0.227–0.881] | 0.378 [0.182–0.782] |

| Stroke | 4.4% | 0.0% | 0.246 | N/A | N/A |

| Cancer | 14.4% | 12.2% | 0.815 | 1.215 [0.450–3.277] | 1.099 [0.390–3.100] |

| Asthma | 15.3% | 9.5% | 0.363 | 1.712 [0.581–5.050] | 1.570 [0.527–4.679] |

| Arthritis | 35.9% | 29.3% | 0.485 | 1.354 [0.662–2.769] | 1.296 [0.592–2.835] |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 10.7% | 17.1% | 0.289 | 0.580 [0.236–1.426] | 0.460 [0.179–1.182] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zundel, C.G.; Krengel, M.H.; Heeren, T.; Yee, M.K.; Grasso, C.M.; Janulewicz Lloyd, P.A.; Coughlin, S.S.; Sullivan, K. Rates of Chronic Medical Conditions in 1991 Gulf War Veterans Compared to the General Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060949

Zundel CG, Krengel MH, Heeren T, Yee MK, Grasso CM, Janulewicz Lloyd PA, Coughlin SS, Sullivan K. Rates of Chronic Medical Conditions in 1991 Gulf War Veterans Compared to the General Population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(6):949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060949

Chicago/Turabian StyleZundel, Clara G., Maxine H. Krengel, Timothy Heeren, Megan K. Yee, Claudia M. Grasso, Patricia A. Janulewicz Lloyd, Steven S. Coughlin, and Kimberly Sullivan. 2019. "Rates of Chronic Medical Conditions in 1991 Gulf War Veterans Compared to the General Population" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 6: 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060949

APA StyleZundel, C. G., Krengel, M. H., Heeren, T., Yee, M. K., Grasso, C. M., Janulewicz Lloyd, P. A., Coughlin, S. S., & Sullivan, K. (2019). Rates of Chronic Medical Conditions in 1991 Gulf War Veterans Compared to the General Population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060949