Cleaning Staff’s Attitudes about Hand Hygiene in a Metropolitan Hospital in Australia: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Focus Group Discussion Guide

References

- Naikoba, S.; Hayward, A. The effectiveness of interventions aimed at increasing handwashing in healthcare workers—A systematic review. J. Hosp. Infect. 2001, 47, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, D.J.; Drey, N.S.; Moralejo, D.; Grimshaw, J.; Chudleigh, J. Interventions to improve hand hygiene compliance in patient care. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 9, CD005186. [Google Scholar]

- Backman, C.; Zoutman, D.E.; Marck, P.B. An integrative review of the current evidence on the relationship between hand hygiene interventions and the incidence of health care-associated infections. Am. J. Infect. Control 2008, 36, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, M.L.; Russo, P.L.; Cruickshank, M.; Bear, J.L.; Gee, C.A.; Hughes, C.F.; Johnson, P.D.; McCann, R.; McMillan, A.J.; Mitchell, B.G.; et al. Outcomes from the first 2 years of the Australian National Hand Hygiene Initiative. Med. J. Australia 2011, 195, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

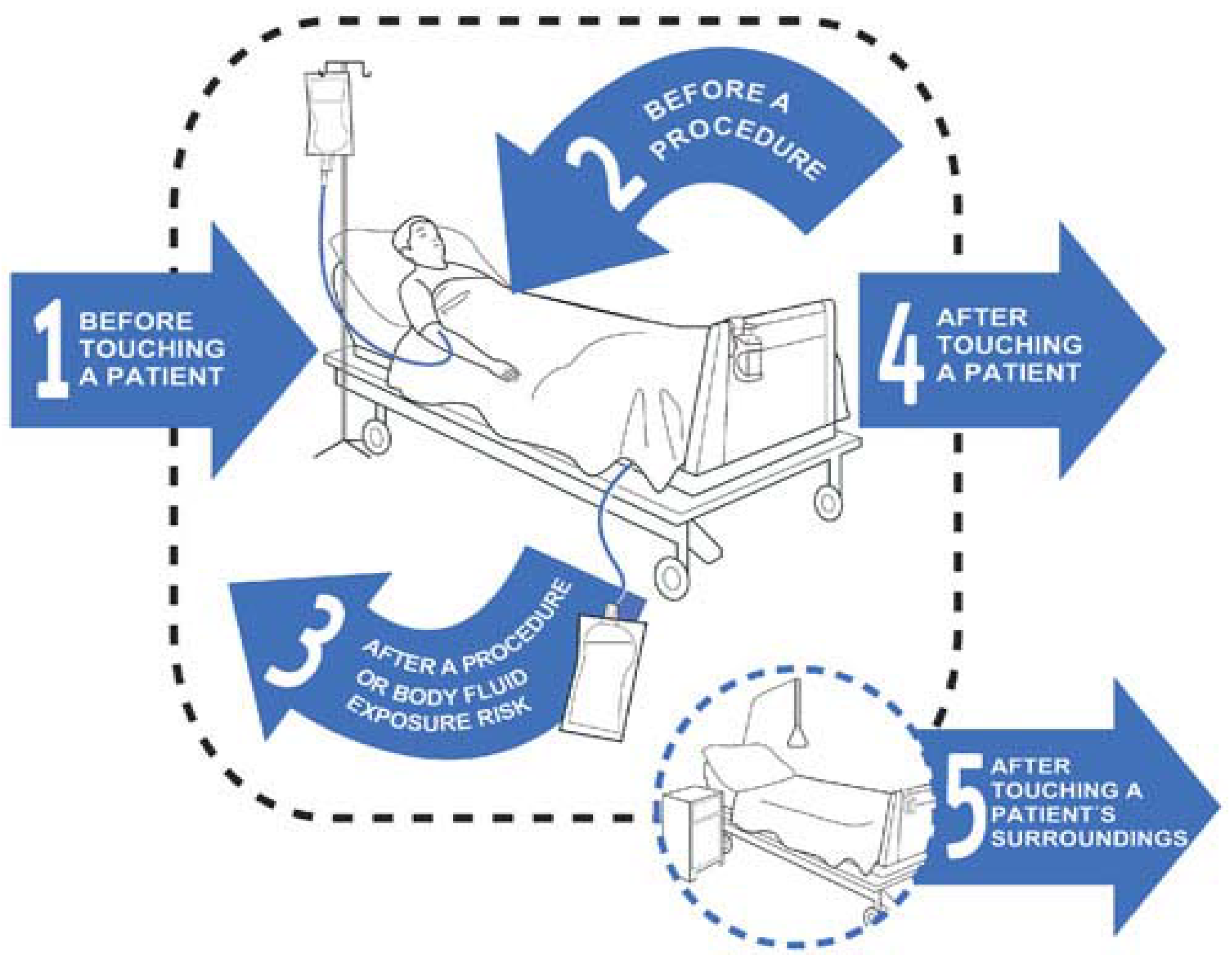

- Hand Hygiene Australia. Five Moments for Hand Hygiene. Available online: https://www.hha.org.au/hand-hygiene/5-moments-for-hand-hygiene (accessed on 22 July 2017).

- Healthcare-Associated Infections | Royal Brisbane & Women’s Hospital | MyHospitals.gov.au. Available online: https://www.myhospitals.gov.au/hospital/310000201/royal-brisbane-and-womens-hospital/healthcare-associated-infectionshttps://www.myhospitals.gov.au/hospital/310000201/royal-brisbane-and-womens-hospital/healthcare-associated-infections (accessed on 16 January 2019).

- Hand Hygiene Australia. Hand Hygiene Australia National Data 2013. Available online: http://www.hha.org.au/LatestNationalData/national-data-for-2013.aspx#PeriodOne2013 (accessed on 22 July 2017).

- Smith, J.; Bekker, H.; Cheater, F. Theoretical versus pragmatic design in qualitative research. Nurse Res. 2011, 18, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liamputtong, P. Qualitative Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: South Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Whitby, M.; McLaws, M.L.; Ross, M.W. Why healthcare workers don’t wash their hands: A behavioural explanation. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2006, 27, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erasmus, V.; Brouwer, W.; van Beeck, E.F.; Oenema, A.; Daha, T.J.; Richardus, J.H.; Vos, M.C.; Brug, J. A qualitative exploration of reasons for poor hand hygiene among hospital workers: Lack of positive role models and of convincing evidence that hand hygiene prevents cross-infection. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2009, 30, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInnes, E.; Philipps, R.; Middleton, S.; Gould, D. A qualitative study of senior hospital managers’ views on current and innovative strategies to improve hand hygiene. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 611. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, J.H.; Wu, S.; Kirzner, D.; Moore, C.; Youssef, G.; Tong, A.; Lourenco, J.; Stewart, R.B.; McCreight, L.J.; Green, K.; et al. Focus group study of hand hygiene practice among healthcare workers in a teaching hospital in Toronto, Canada. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010, 31, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Pittlet, D. Improving hand hygiene compliance in healthcare settings using behaviour change theories. Teach. Learn. Med. 2013, 25, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsalve, M.N.; Pemmaraju, S.V.; Thomas, G.W.; Herman, T.; Segre, A.M.; Polgreen, P.M. Do peer effects improve hand hygiene adherence among healthcare workers? Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2014, 35, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumbler, E.; Castillo, L.; Satorie, L.; Ford, D.; Hagman, J.; Hodge, T.; Price, L.; Wald, H. Culture change in infection control: Applying psychological principles to improve hand hygiene. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2013, 28, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand Hygiene Australia. 2012. Available online: http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/HH-Outcomes.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2017).

- Hui, S.; Ng, J.; Santiano, N.; Schmidt, H.M.; Caldwell, J.; Ryan, E.; Maley, M. Improving hand hygiene compliance: Harnessing the effect of advertised auditing. Healthc. Infect. 2014, 19, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.C.; Tien, K.L.; Hung, I.C.; Lin, Y.J.; Sheng, W.H.; Wang, M.J.; Chang, S.C.; Kunin, C.M.; Chen, Y.C. Compliance of health care workers with hand hygiene practices: Independent advantages of overt and covert observers. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.C. Qualitative study on perceptions of hand hygiene among hospital staff in a rural teaching hospital in India. J. Hosp. Infect. 2012, 80, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harne-Britner, S.; Allen, M.; Fowler, K. Improving hand hygiene adherence among nursing staff. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2011, 26, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhenn, A.S.; Yousef, A.; Mhawsh, M.; Alqudah, N. Hand hygiene championship: A direct observational study. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2013, 34, 1126–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National Hand Hygiene Initiative. 2015. Available online: http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/healthcare-associated-infection/hand-hygiene (accessed on 22 July 2017).

- Ryan, K.; Russo, P.L.; Havers, S.; Bellis, K.; Grayson, M.L. Development of a standardised approach to observing hand hygiene compliance in Australia. Healthc. Infect. 2012, 17, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantle, A.; Fitzpatrick, K. Clean Hands Save Lives: Final Report of the NSW Hand Hygiene Campaign; Clinical Excellence Commission: Sydney, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Alshehari, A.; Park, S.; Rashid, H. Strategies to improve hand hygiene compliance among healthcare workers in adult intensive care units: A mini systematic review. J. Hosp. Inf. 2018, 100, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felembam, O.; John, W.S.; Shaban, R.Z. Hand hygiene practices of home visiting community nurses: Perceptions, compliance, techniques and contextual factors of practice using the World Health Organisation’s ‘Five Moments for Hand Hygiene’. Home Health Nurs. 2012, 30, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hor, S.; Hooker, C.; Iedema, R.; Wyer, M.; Gilbert, G.L.; Jorm, C.; O’sullivan, M.V.N. Beyond hand hygiene: A qualitative study of the everyday work of preventing cross-contamination on hospital wards. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2017, 26, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, S.; Gray, T.; Gottlieb, T. Healthcare-acquired infections: Prevention strategies. Intern. Med. J. 2017, 27, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grayson, M.L.; Stewardson, A.J.; Russo, P.L.; Ryan, K.E.; Olsen, K.L.; Havers, S.M.; Greig, S.; Cruickshank, M.; Hand Hygiene Australia; The National Hand Hygiene Initiative. Effects of the Australian National Hand Hygiene Initiative after 8 years on infection control practices, health-care worker education, and clinical outcomes: A longitudinal study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018, 18, 1269–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, M.L.; Macesic, N.; Huang, G.K.; Bond, K.; Fletcher, J.; Gilbert, G.L.; Gordon, D.L.; Hellsten, J.F.; Iredell, J.; Keighley, C.; et al. Use of an Innovative Personality-Mindset Profiling Tool to Guide Culture-Change Strategies among Different Healthcare Worker Groups. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Count | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 5 | 42% |

| Male | 7 | 58% | |

| Age | <30 years | 1 | 8% |

| 30–50 years | 5 | 42% | |

| >50 years | 6 | 50% | |

| Time employed as a cleaner at this facility | 0–3 years | 3 | 25% |

| 3–10 years | 4 | 33% | |

| >10 years | 5 | 42% | |

| How important is hand hygiene (scale 1–10) | Very important (score 10) | 12 | 100% |

| How hard is hand hygiene (scale 1–10) | Very easy (score 10) | 12 | 100% |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sendall, M.C.; McCosker, L.K.; Halton, K. Cleaning Staff’s Attitudes about Hand Hygiene in a Metropolitan Hospital in Australia: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16061067

Sendall MC, McCosker LK, Halton K. Cleaning Staff’s Attitudes about Hand Hygiene in a Metropolitan Hospital in Australia: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(6):1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16061067

Chicago/Turabian StyleSendall, Marguerite C., Laura K. McCosker, and Kate Halton. 2019. "Cleaning Staff’s Attitudes about Hand Hygiene in a Metropolitan Hospital in Australia: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 6: 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16061067

APA StyleSendall, M. C., McCosker, L. K., & Halton, K. (2019). Cleaning Staff’s Attitudes about Hand Hygiene in a Metropolitan Hospital in Australia: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16061067