It Doesn’t End There: Workplace Bullying, Work-to-Family Conflict, and Employee Well-Being in Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical and Empirical Background Linking Workplace Bullying to Employee Well-Being

1.2. Work-to-Family Conflict as a Mediating Mechanism

1.3. Extent of Workplace Bullying in Korean Workplaces

1.4. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Workplace Bullying

2.2.2. Work-to-Family Conflict

2.2.3. Quality of Life

2.2.4. Occupational Health

2.2.5. Covariates

2.3. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Zapf, D.; Cooper, C.L. The concept of bullying and harassment at work: The European tradition. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice; Einarsen, S., Ed.; Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; pp. 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- Leymann, H. The content and development of mobbing at work. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1996, 5, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samnani, A.K.; Singh, P. 20 Years of workplace bullying research: A review of the antecedents and consequences of bullying in the workplace. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2012, 17, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y. Workplace bullying in Korea. KRIVET Issue Br. 2013, 20, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Y. The state of workplace bullying by job sector in Korea. KRIVET Issue Br. 2015, 77, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, A.; Agarwal, U. Workplace bullying: A review and future research directions. South Asian J. Manag. 2016, 23, 27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Marks, N.F. Reconceptualizing the work-family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Parasuraman, S. A work-nonwork interactive perspective of stress and its consequences. J. Organ. Behav. Manag. 1987, 8, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoobler, J.M.; Brass, D.J. Abusive supervision and family undermining as displaced aggression. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, D.; Ferguson, M.; Hunter, E.; Whitten, D. Abusive supervision and work-family conflict: The path through emotional labor and burnout. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.; Ferguson, M.; Perrewe, P.L.; Whitten, D. The fallout from abusive supervision: An examiniation of subordinates and their partners. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 937–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B.J. Consequences of abusive supervision. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 178–190. [Google Scholar]

- Buxton, O.M.; Lee, S.; Beverly, C.; Berkman, L.F.; Moen, P.; Kelly, E.L.; Hammer, L.B.; Almeida, D.M. Work-family conflict and employee sleep: Evidence from IT workers in the Work, Family and Health Study. Sleep 2016, 39, 1871–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geurts, S.; Rutte, C.; Peeters, M. Antecedents and consequences of work–home interference among medical residents. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 48, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, U.; Geurts, S.; Mauno, S. Work-to-family conflict and its relationship with satisfaction and well-being: A one-year longitudinal study on gender differences. Work Stress 2004, 18, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lange, A.H.; Taris, T.W.; Kompier, M.A.J.; Houtman, I.L.D.; Bongers, P.M. “The very best of the millennium”: Longitudinal research and the demand-control-(support) model. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2003, 8, 282–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Davis, K.D.; Neuendorf, C.; Grandey, A.; Lam, C.B.; Almeida, D.M. Individual- and organization-level work-to-family spillover are uniquely associated with hotel managers’ work exhaustion and satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, M.; Kümmerling, A.; Hasselhorn, H.M. Work-home conflict in the European nursing profession. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2004, 10, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, L.T.; Ganster, D.C. Impact of family-supportive work variables on work-family conflict and strain: A control perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 1995, 80, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, D.T.; Barnes, C.M.; Scott, B.A. Driving it home: How workplace emotional labor harms employee home life. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 67, 487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, N.K.; Breaugh, J.A. Family-friendly policies, supervisor support, work-family conflict, family-work conflict, and satisfaction: A test of a conceptual model. J. Bus. Psychol. 2004, 19, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Kwan, H.K.; Lee, C.; Hui, C. Work-to-family spillover effects of workplace ostracism: The role of work-home segmentation preferences. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 52, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, D. Negative spillover impact of perceptions of organizational politics on work-family conflict in China. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2015, 43, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S. Harassment and bullying at work: A review of the Scandinavian approach. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2000, 5, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquadro Maran, D.; Varetto, A.; Zedda, M.; Magnavita, N. Workplace violence toward hospital staff and volunteers: A survey of an Italian sample. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2018, 27, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquadro Maran, D.; Varetto, A.; Zedda, M.; Franscini, M. Health care professionals as victims of stalking: Characteristics of the stalking campaign, consequences, and motivation in Italy. J. Interpers. Violence 2017, 32, 2605–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauge, L.J.; Skogstad, A.; Einarsen, S. Relationships between stressful work environments and bullying: Results of a large representative study. Work Stress 2007, 21, 220–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, A.; Giorgi, G.; Montani, F.; Mancuso, S.; Perez, J.F.; Mucci, N.; Arcangeli, G. Workplace bullying in a sample of italian and spanish employees and its relationship with job satisfaction, and psychological well-being. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casimir, G.; McCormack, D.; Djurkovic, N.; Nsubuga-Kyobe, A. Psychosomatic model of workplace bullying: Australian and Ugandan schoolteachers. Empl. Relat. 2012, 34, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehue, F.; Bolman, C.; Völlink, T.; Pouwelse, M. Coping with bullying at work and health related problems. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2012, 19, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahtahmasebi, S. Quality of life: A case report of bullying in the workplace. Sci. World J. 2004, 4, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vartia, M.A.L. Consequences of workplace bullying with respect to the well-being of its targets and the observers of bullying. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2001, 27, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonde, J.P.; Gullander, M.; Hansen, Å.M.; Grynderup, M.; Persson, R.; Hogh, A.; Willert, M.V.; Kaerlev, L.; Rugulies, R.; Kolstad, H.A. Health correlates of workplace bullying: A 3-wave prospective follow-up study. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2016, 42, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, J.R.; Rothbard, N.P. Mechanisms linking work and family: Clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M.R.; Russell, M.; Cooper, M.L. Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. J. Appl. Psychol. 1992, 77, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voydanoff, P. Toward a conceptualization of perceived work-family fit and balance: A demands and resources approach. J. Marriage Fam. 2005, 67, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voydanoff, P. The effects of work demands and resources on work-to-family conflict and facilitation. J. Marriage Fam. 2004, 66, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trépanier, S.G.; Fernet, C.; Austin, S. Workplace bullying and psychological health at work: The mediating role of satisfaction of needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness. Work Stress 2013, 27, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, F.; Fletcher, B.C. An empirical study of occupational stress transmission in working couples. Hum. Relat. 1993, 46, 881–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Vergel, A.I.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, A. The effect of workplace bullying on health: The mediating role of work-family conflict. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2011, 27, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, G. The effects of Confucian work views and gender role attitudes on job & family involvements and demands for family-friendly policies. J. Fam. Relat. 2010, 14, 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.A. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions: Comparison of South Korea and the United States. In Proceedings of the 2015 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference, Cambridge, UK, 1–2 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Bond, M.H. The Confucius connection: From cultural roots to economic growth. Organ. Dyn. 1988, 16, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Duvander, A.-Z.; Zarit, S.H. How can family policies reconcile fertility and women’s employment? Comparisons between South Korea and Sweden. Asian J. Women’s Stud. 2016, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E. The influence of Confucian work value on the job involvement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Korean J. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2001, 14, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Y.N.; Leather, P.; Coyne, I. South Korean culture and history: The implications for workplace bullying. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2012, 17, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Nurses Not Adequately Covered by the Psychological Counseling Service. Available online: http://news.donga.com/3/all/20180221/88765753/1 (accessed on 21 February 2018).

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H. Measuring Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace. Development and Validity of the Revised Negative Acts Questionnaire: A Manual; University of Bergen: Bergen, Norway, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Bass, B.L. Work, family, and mental health: Testing different models of work-family fit. J. Marriage Fam. 2003, 65, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.H.; Barnes, H.L. Quality of life. In Family Social Science; Olson, D.H., McCubbin, H.I., Barnes, H.L., Larsen, A.S., Muxen, M., Wilson, M., Eds.; University of Minnesota: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zoller, H.M. Health on the line: Identity and disciplinary control in employee occupational health and safety discourse. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2003, 31, 118–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A.; Jenkins, D.A. The happy-productive worker thesis revisited. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, E.L.; Moen, P.; Oakes, J.M.; Fan, W.; Okechukwu, C.; Davis, K.D.; Hammer, L.B.; Kossek, E.E.; King, R.B.; Hanson, G.C.; et al. Changing work and work-family conflict: Evidence from the Work, Family, and Health Network. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2014, 79, 485–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, D.M.; Lee, S.; Walter, K.N.; Lawson, K.M.; Kelly, E.L.; Buxton, O.M. The effects of a workplace intervention on employees’ cortisol awakening response. Community Work Fam. 2018, 21, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, D.E.; Pattison, P.; Bible, J.D. Legislating “NICE”: Analysis and assessment of proposed workplace bullying prohibitions. South Law J. 2012, 22, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Squelch, J.; Guthrie, R. The Australian legal framework for workplace bullying. Comp. Labor Law Policy J. 2010, 32, 15–54. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen, K.; Mykletun, R.J.; Einarsen, S.V.; Skogstad, A.; Salin, D. Ethical infrastructure and successful handling of workplace bullying. Nord. J. Work Life Stud. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method variance in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoel, H.; Cooper, C.L.; Faragher, B. The experience of bullying in Great Britain: The impact of organizational status. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2001, 10, 443–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (N = 307) | Healthcare (n = 105) | Education (n = 88) | Banking (n = 114) | Difference Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M or % | (SD) | M or % | (SD) | M or % | (SD) | M or % | (SD) | χ2 or F-test | |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||||||

| Age | 42.85 | (8.01) | 41.28b | (7.99) | 43.07ab | (8.52) | 44.14a | (7.41) | 3.60 * |

| Gender (%) | 15.41 *** | ||||||||

| Male | 38.76 | 46.67 | 21.59 | ||||||

| Female | 61.24 | 53.33 | 78.41 | 44.74 | |||||

| Education (%) | 55.26 | 31.59 *** | |||||||

| College graduate or higher | 70.03 | 69.52 | 90.91 | 54.39 | |||||

| Under college graduate | 29.97 | 30.48 | 9.09 | 45.61 | |||||

| Work hours (per week) | 43.83 | (6.22) | 43.34b | (4.44) | 41.89b | (4.00) | 45.78a | (8.20) | 10.89 *** |

| Main variables | |||||||||

| Workplace bullying | 5.30 | (5.33) | 6.00a | (5.56) | 3.64b | (3.95) | 5.95a | (5.77) | 6.25 ** |

| Work-to-family conflict | 2.97 | (0.79) | 2.88 | (0.86) | 2.94 | (0.76) | 3.07 | (0.73) | 1.58 |

| Quality of life | 3.62 | (0.61) | 3.58 | (0.60) | 3.74 | (0.61) | 3.55 | (0.61) | 2.70 |

| Occupational health | 3.19 | (0.88) | 3.16ab | (0.94) | 3.44a | (0.79) | 3.03b | (0.84) | 5.89 ** |

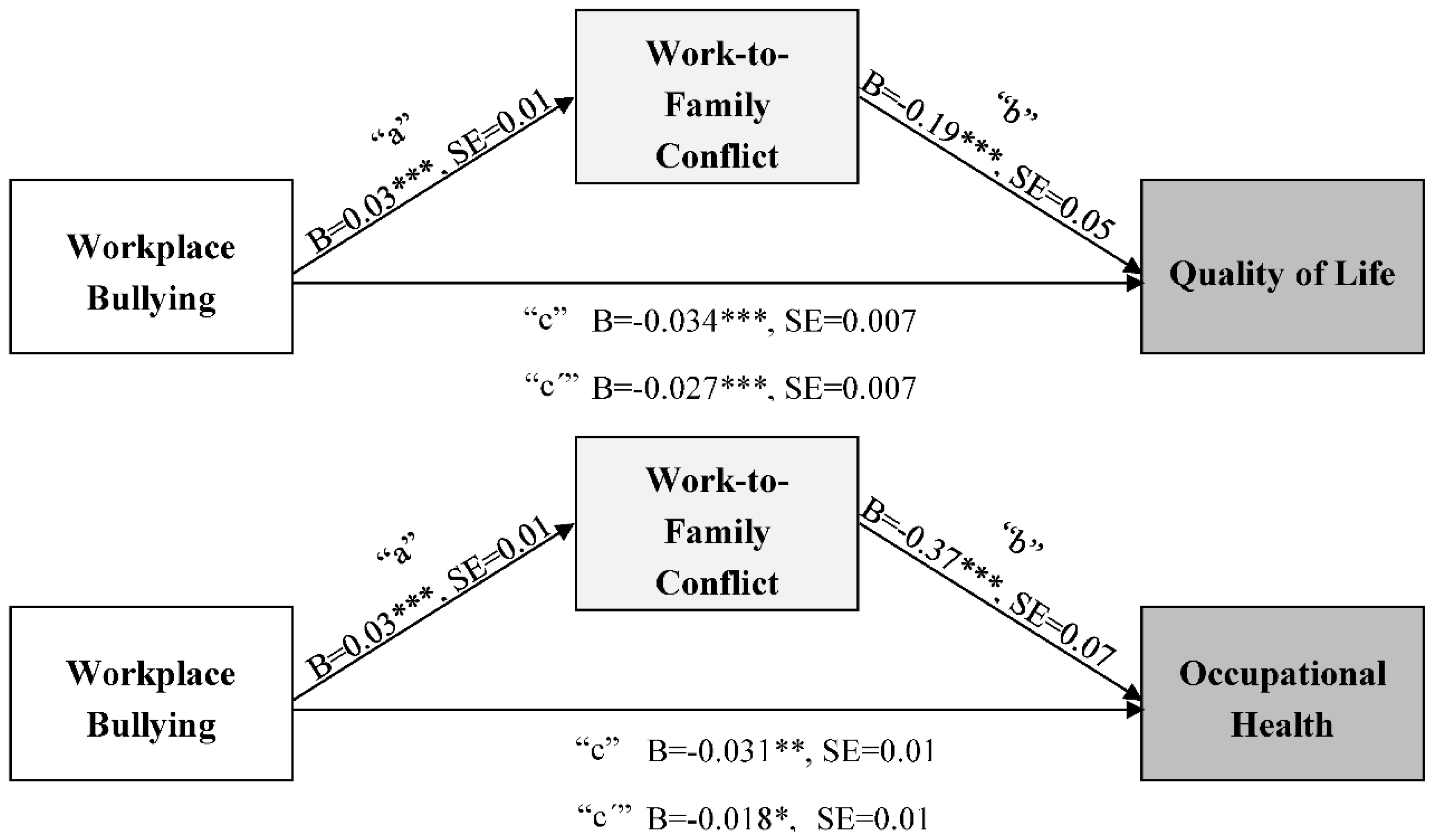

| M: Work-to-Family Conflict | Y: Quality of Life | |||||

| B | (SE) | B | (SE) | |||

| Intercept | −0.45 | *** | (0.10) | 3.55 | *** | (0.08) |

| X: Workplace bullying | 0.03 | *** | (0.01) | −0.03 | *** | (0.01) |

| M: Work-to-family conflict | -- | -- | −0.19 | *** | (0.05) | |

| Industry, Healthcare (vs. Banking) | −0.22 | * | (0.10) | −0.02 | (0.08) | |

| Industry, Education (vs. Banking) | −0.26 | * | (0.11) | 0.08 | (0.09) | |

| Age | −0.01 | (0.01) | 0.00 | (0.00) | ||

| Women (vs. Men) | 0.54 | *** | (0.09) | 0.01 | (0.07) | |

| College graduates or higher (vs. Not) | 0.38 | *** | (0.10) | 0.07 | (0.08) | |

| Work hours (per week) | 0.01 | * | (0.01) | 0.00 | (0.01) | |

| R2 = 0.2285 | R2 = 0.1553 | |||||

| F(7299) = 12.65 *** | F(8298) = 6.85 *** | |||||

| Indirect Effect of X on Y: B = −0.01 **, SE = 0.002 95% CI = −0.0121 to −0.0129 | ||||||

| M: Work-to-Family Conflict | Y: Occupational Health | |||||

| B | (SE) | B | (SE) | |||

| Intercept | −0.45 | *** | (0.10) | 3.04 | *** | (0.12) |

| X: Workplace bullying | 0.03 | *** | (0.01) | −0.02 | * | (0.01) |

| M: Work-to-family conflict | -- | -- | −0.37 | *** | (0.07) | |

| Industry, Healthcare (vs. Banking) | −0.22 | * | (0.10) | 0.13 | (0.11) | |

| Industry, Education (vs. Banking) | −0.26 | * | (0.11) | 0.36 | ** | (0.13) |

| Age | −0.01 | (0.01) | 0.02 | ** | (0.01) | |

| Women (vs. Men) | 0.54 | *** | (0.09) | 0.03 | (0.10) | |

| College graduates or higher (vs. Not) | 0.38 | *** | (0.10) | −0.03 | (0.11) | |

| Work hours (per week) | 0.01 | * | (0.01) | 0.00 | (0.01) | |

| R2 = 0.2285 | R2 = 0.2035 | |||||

| F(7299) = 12.65 *** | F(8298) = 9.52 *** | |||||

| Indirect Effect of X on Y: B = −0.01***, SE = 0.004 95% CI = −0.0214 to −0.0064 | ||||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoo, G.; Lee, S. It Doesn’t End There: Workplace Bullying, Work-to-Family Conflict, and Employee Well-Being in Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071548

Yoo G, Lee S. It Doesn’t End There: Workplace Bullying, Work-to-Family Conflict, and Employee Well-Being in Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(7):1548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071548

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoo, Gyesook, and Soomi Lee. 2018. "It Doesn’t End There: Workplace Bullying, Work-to-Family Conflict, and Employee Well-Being in Korea" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 7: 1548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071548

APA StyleYoo, G., & Lee, S. (2018). It Doesn’t End There: Workplace Bullying, Work-to-Family Conflict, and Employee Well-Being in Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(7), 1548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071548