Reconsidering the Relationship between Air Pollution and Deprivation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

A More Pluralistic Theoretical Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analytical Approach

2.2. Data

3. Results and Discussions

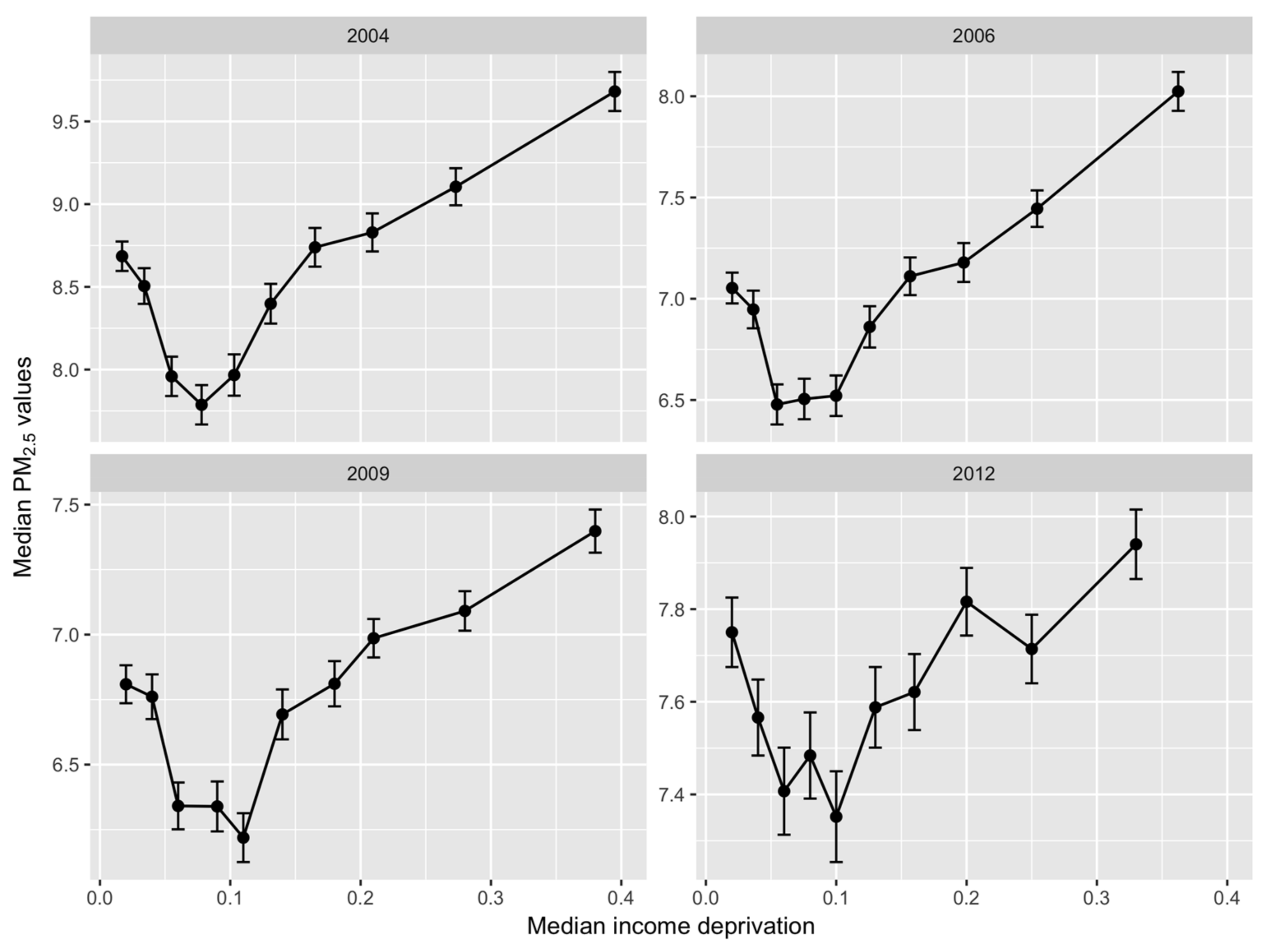

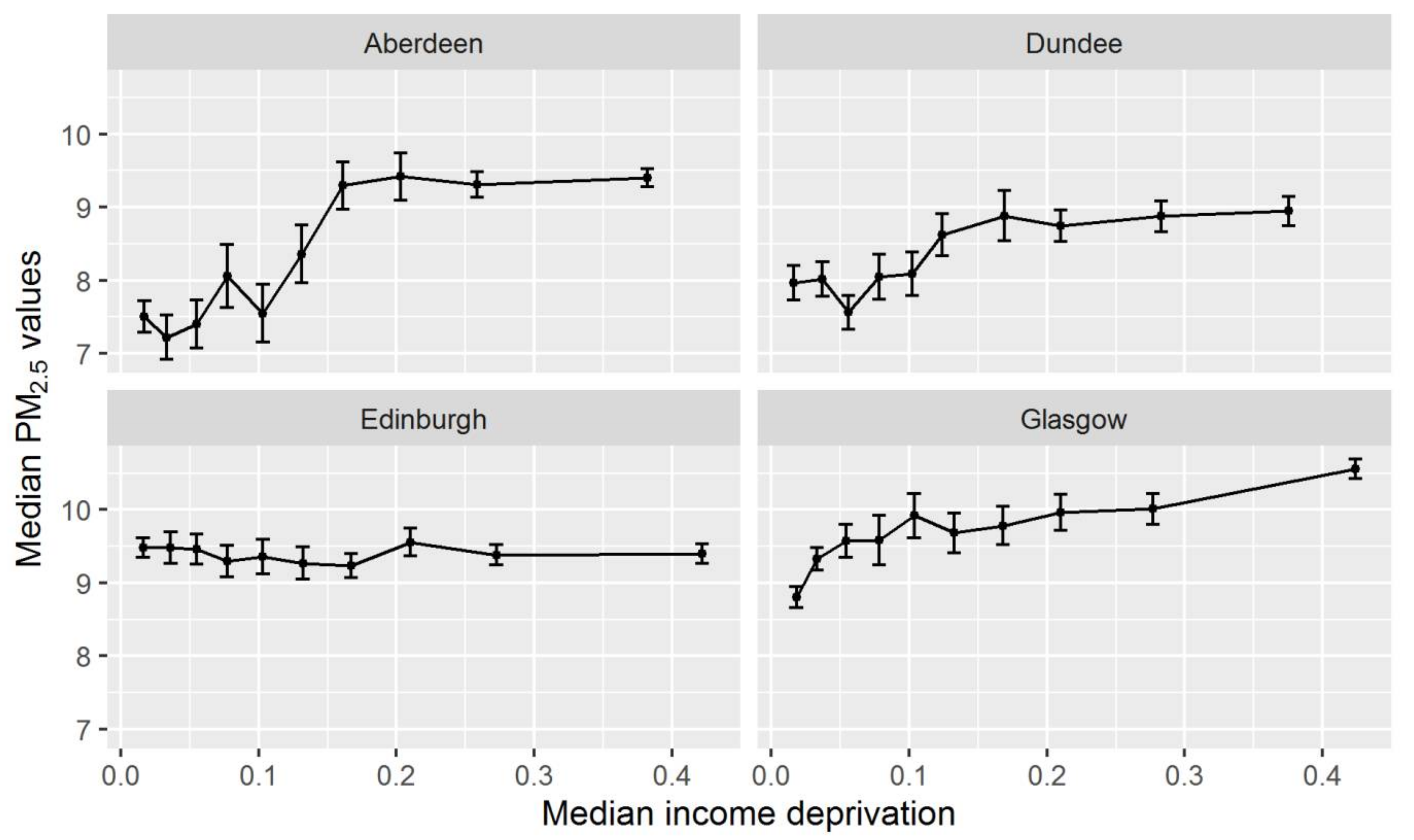

3.1. Explore Relationships without Imposing Functional Form

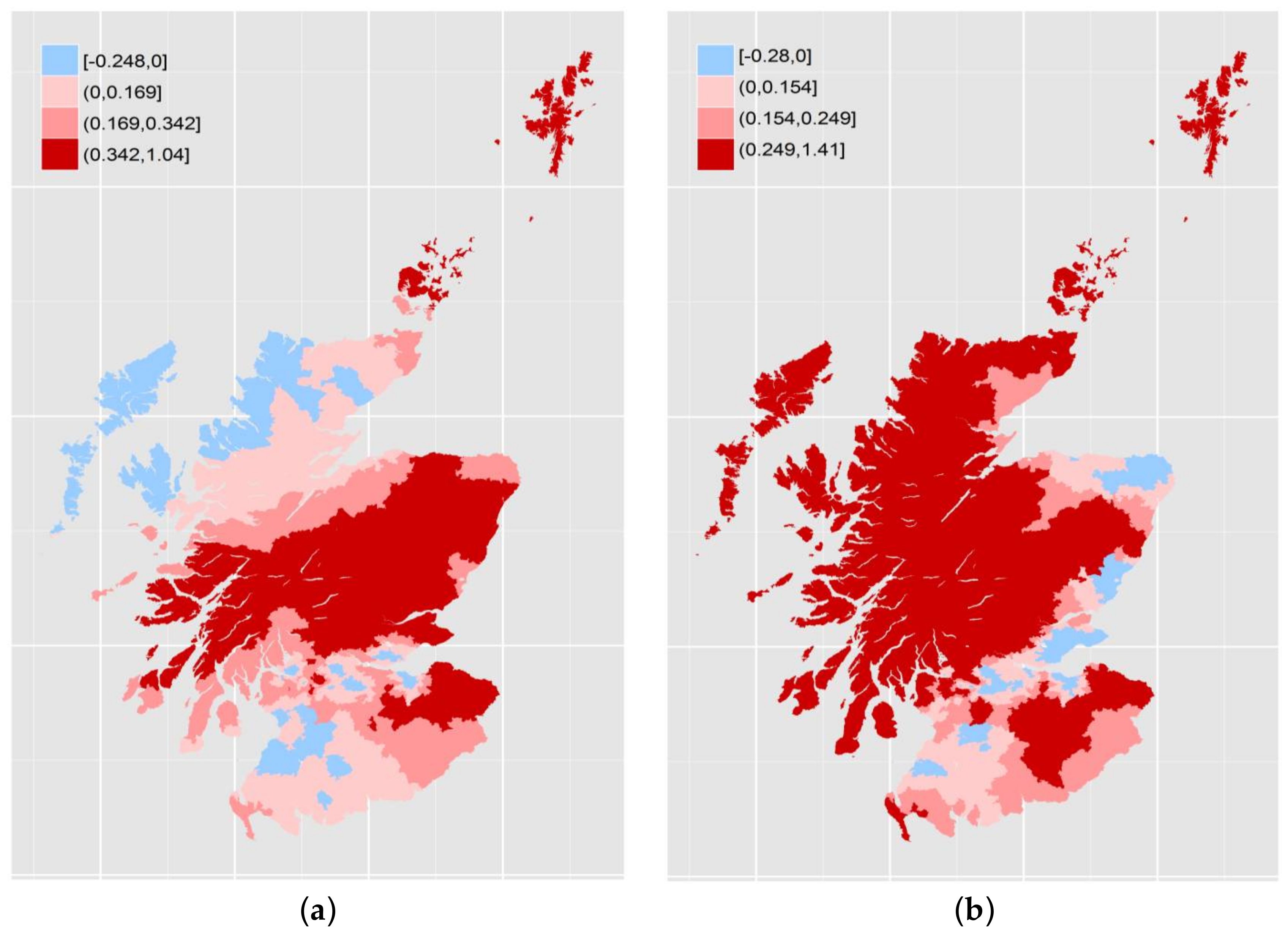

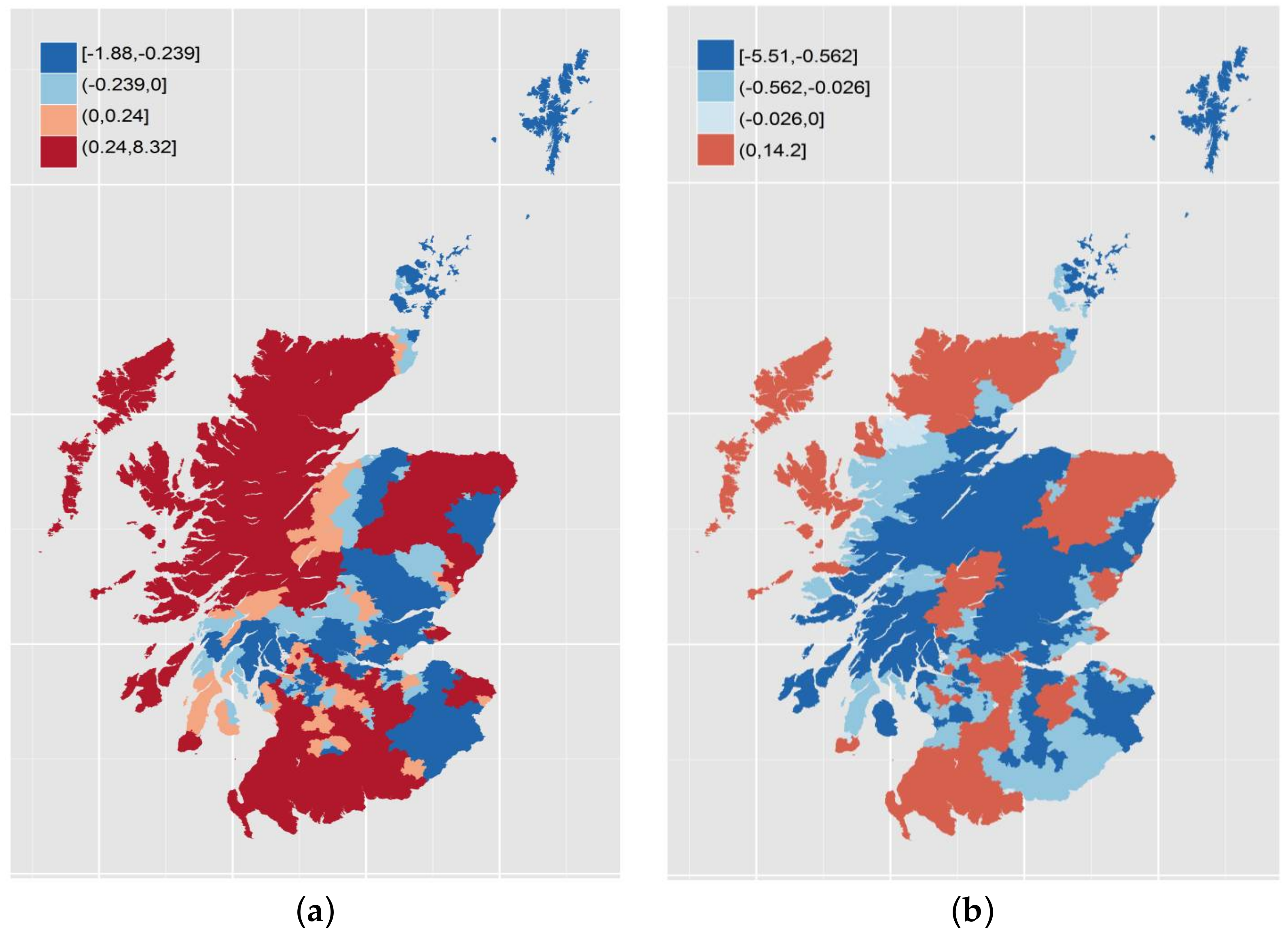

3.2. Local Spatial Non-Linear Analysis

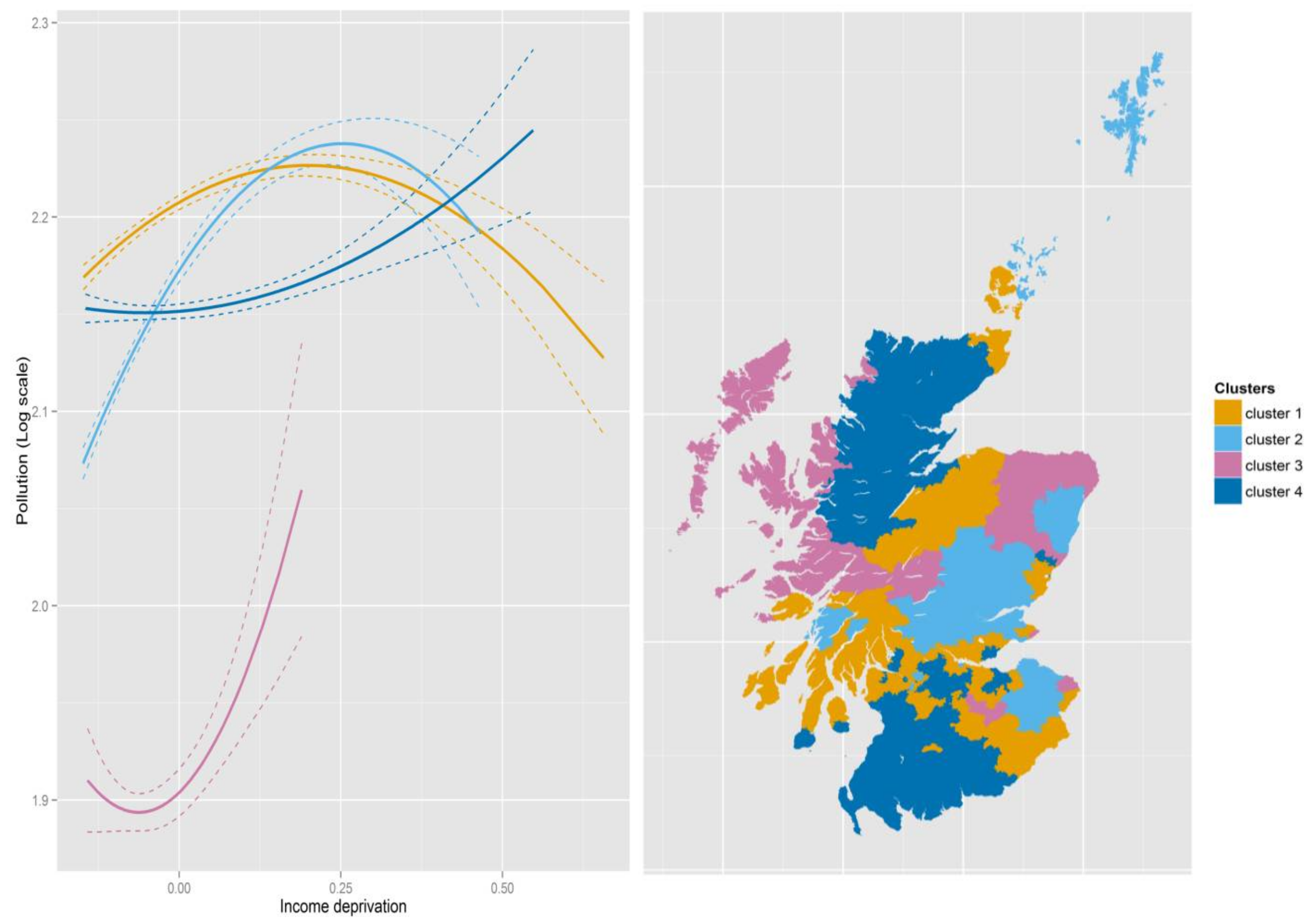

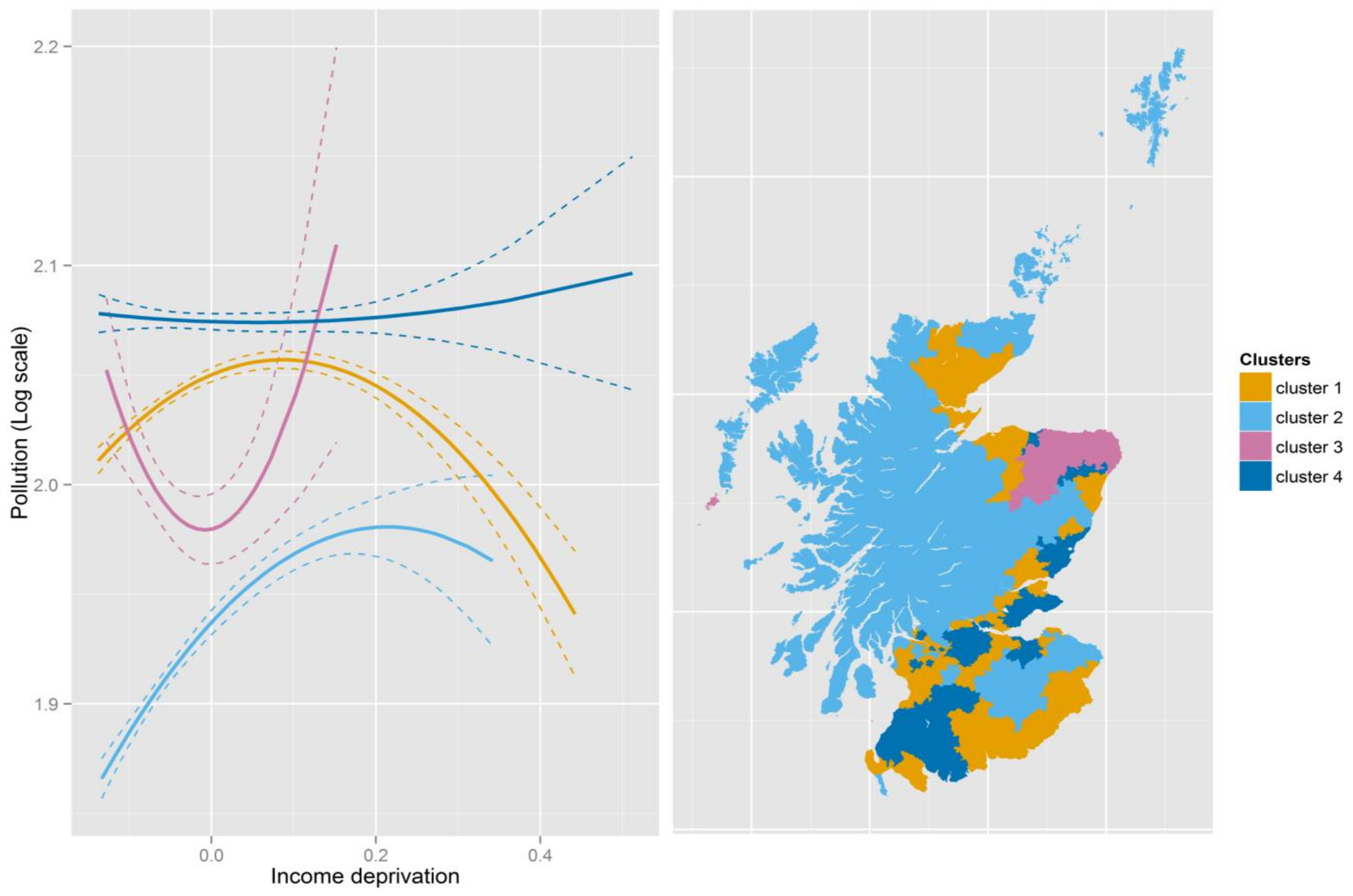

3.3. Identifying Regions

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vaughan, A. Diesel Cars in London Increase Despite Air Pollution Warnings. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/jun/15/diesel-vehicles-take-record-share-of-the-market-on-londons-roads (accessed on 28 March 2018).

- Physicians, R.C.O. Every Breath We Take: The Lifelong Impact of Air Pollution; RCP: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, W. An analytical review of environmental justice research: What do we really know? Environ. Manag. 2002, 29, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depro, B.; Timmins, C.; O’Neil, M. White flight and coming to the nuisance: Can residential mobility explain environmental injustice? J. Assoc. Environ. Res. Econ. 2015, 2, 439–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, G.; Dorling, D. An environmental justice analysis of British air quality. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 909–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.L.; Ebisu, K. Environmental inequality in exposures to airborne particulate matter components in the United States. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brainard, J.S.; Jones, A.P.; Bateman, I.J.; Lovett, A.A.; Fallon, P.J. Modelling environmental equity: Access to air quality in Birmingham, England. Environ. Plan. A 2002, 34, 695–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedley, A.J.; McGhee, S.M.; Barron, B.; Chau, P.; Chau, J.; Thach, T.Q.; Wong, T.-W.; Loh, C.; Wong, C.-M. Air pollution: Costs and paths to a solution in Hong Kong—Understanding the connections among visibility, air pollution, and health costs in pursuit of accountability, environmental justice, and health protection. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 2008, 71, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla, C.M.; Kihal-Talantikite, W.; Vieira, V.M.; Rossello, P.; Le Nir, G.; Zmirou-Navier, D.; Deguen, S. Air quality and social deprivation in four French Metropolitan areas—A localized Spatio-temporal environmental inequality analysis. Environ. Res. 2014, 134, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, J.; Kingham, S. Environmental inequalities in New Zealand: A national study of air pollution and environmental justice. Geoforum 2008, 39, 980–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryce, G.; Chen, Y.; Galster, G. The impact of floods on house prices: An imperfect information approach with myopia and amnesia. Hous. Stud. 2011, 26, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiebout, C.M. A pure theory of local expenditures. J. Political Econ. 1956, 64, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, G.; Norman, P.; Mullin, K. Who benefits from environmental policy? An environmental justice analysis of air quality change in britain, 2001–2011. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 105009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galster, G. On the nature of neighbourhood. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 2111–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-H.; Bowker, J.M.; Park, W.M. Measuring the contribution of water and green space amenities to housing values: An application and comparison of spatially weighted hedonic models. J. Agric. Res. Econ. 2006, 485–507. [Google Scholar]

- Geoghegan, J. The value of open spaces in residential land use. Land Use Policy 2002, 19, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjestland, A.; McArthur, D.P.; Osland, L.; Thorsen, I. The suitability of hedonic models for cost-benefit analysis: Evidence from commuting flows. Transp. Res. Part A Policy and Pract. 2014, 61, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.R.; Jones, W.H. Hedonic property valuation models: Are subjective measures of neighborhood amenities needed? Real Estate Econ. 1979, 7, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Dong, G. Valuing the “green” amenities in a spatial context. J. Reg. Sci. 2014, 54, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlauf, S.N. Chapter 50 Neighborhood effects. In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 4, pp. 2173–2242. [Google Scholar]

- Hamnett, C. The blind men and the elephant: The explanation of gentrification. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1991, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, H. ‘Smoke cities’: Northern industrial towns in late Georgian England. Urban Hist. 2004, 31, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosley, S. The Chimney of the World: A History of Smoke Pollution in Victorian and Edwardian Manchester; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, T. Towards a politics of mobility. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2010, 28, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellegård, K.; Vilhelmson, B. Home as a pocket of local order: Everyday activities and the friction of distance. Geograf. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2004, 86, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoma, M.; Mikkonen, K.; Palomäki, M. The threshold gravity model and transport geography: How transport development influences the distance-decay parameter of the gravity model. J. Transp. Geogr. 1993, 1, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkonen, K.; Luoma, M. The parameters of the gravity model are changing–how and why? J. Transp. Geogr. 1999, 7, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Knox, P.L. Spatial transformation of metropolitan cities. Environ. Plan. A 2015, 47, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, R. On form versus function: Will the new urbanism reduce traffic, or increase it? J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1996, 15, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, C. Happy City: Transforming Our Lives through Urban Design; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Næss, P.; Strand, A.; Næss, T.; Nicolaisen, M. On their road to sustainability?: The challenge of sustainable mobility in urban planning and development in two Scandinavian capital regions. Town Plan. Rev. 2011, 82, 285–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, N.; Kearns, A.; Livingston, M. Place attachment in deprived neighbourhoods: The impacts of population turnover and social mix. Hous. Stud. 2012, 27, 208–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.B., Jr. Requiem for large-scale models. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1973, 39, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Brömmelstroet, M.; Pelzer, P.; Geertman, S. Forty years after lee’s requiem: Are we beyond the seven sins? Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2014, 41, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D.; McIntosh, I.; Smyth, J. Neighbourhood identity: The path dependency of class and place. Hous. Theory Soc. 2010, 27, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, A.; Dean, J. Challenging images: Tackling stigma through estate regeneration. Policy Politics 2003, 31, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, A.; Bailey, N.; Bramley, G.; Croudace, R.; Watkins, D. ‘Managing’the middle classes: Urban managers, public services and the response to middle-class capture. Local Gov. Stud. 2014, 40, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawson, H.; Kintrea, K. Part of the problem or part of the solution? Social housing allocation policies and social exclusion in Britain. J. Soc. Policy 2002, 31, 643–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harloe, M. Social justice and the city: The new ‘liberal formulation’. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2001, 25, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Brunsdon, C.; Charlton, M. Geographically Weighted Regression: The Analysis of Spatially Varying Relationships; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Páez, A.; Uchida, T.; Miyamoto, K. A general framework for estimation and inference of geographically weighted regression models: 1. Location-specific kernel bandwidths and a test for locational heterogeneity. Environ. Plan. A 2002, 34, 733–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, M.; Mulligan, G. Using geographically weighted regression to explore local crime patterns. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2007, 25, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. The Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation. 2012. Available online: http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/SIMD (accessed on 28 March 2018).

- DEFRA. What Are the Causes of Air Pollution? Available online: http://uk-air.defra.gov.uk/assets/documents/What_are_the_causes_of_Air_Pollution.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2018).

- Brunsdon, C.; Fotheringham, A.S.; Charlton, M. Some notes on parametric significance tests for geographically weighted regression. J. Reg. Sci. 1999, 39, 497–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Y.; Mei, C.-L.; Zhang, W.-X. Statistical tests for spatial nonstationarity based on the geographically weighted regression model. Environ. Plan. A 2000, 32, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Income Deprivation | Mean | Std. Dev | Lower Quantile | Upper Quantile |

| 2004 | 0.149 | 0.121 | 0.055 | 0.209 |

| 2006 | 0.141 | 0.110 | 0.055 | 0.198 |

| 2009 | 0.154 | 0.113 | 0.060 | 0.210 |

| 2012 | 0.138 | 0.098 | 0.060 | 0.200 |

| Air Pollution (PM2.5 Micrograms/m3 (μg m−3)) | Mean | Std. Dev | Lower Quantile | Upper Quantile |

| National | ||||

| 2004 | 8.630 | 1.542 | 7.422 | 9.607 |

| 2006 | 7.088 | 1.284 | 6.205 | 7.937 |

| 2009 | 6.779 | 1.135 | 5.995 | 7.523 |

| 2012 | 7.557 | 1.087 | 6.888 | 8.236 |

| Aberdeen | ||||

| 2004 | 8.247 | 1.308 | 7.092 | 9.363 |

| 2006 | 6.523 | 1.024 | 5.630 | 7.338 |

| 2009 | 6.924 | 1.158 | 6.078 | 7.797 |

| 2012 | 8.169 | 0.887 | 7.677 | 8.665 |

| Dundee | ||||

| 2004 | 8.404 | 0.750 | 7.785 | 8.981 |

| 2006 | 7.455 | 1.233 | 6.264 | 8.328 |

| 2009 | 6.680 | 0.622 | 6.122 | 7.059 |

| 2012 | 7.609 | 0.448 | 7.325 | 7.921 |

| Edinburgh | ||||

| 2004 | 9.442 | 0.865 | 8.952 | 9.935 |

| 2006 | 7.716 | 0.765 | 7.122 | 8.271 |

| 2009 | 7.508 | 0.813 | 7.100 | 7.962 |

| 2012 | 8.497 | 0.701 | 8.130 | 8.874 |

| Glasgow | ||||

| 2004 | 9.986 | 1.357 | 8.967 | 10.878 |

| 2006 | 8.321 | 1.069 | 7.507 | 8.946 |

| 2009 | 7.602 | 0.947 | 6.965 | 8.057 |

| 2012 | 8.066 | 0.954 | 7.427 | 8.552 |

| Variables | National Scale | Aberdeen | Dundee | Glasgow | Edinburgh | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | 2004 | 2012 | |

| Coefficients/(Std. Err) | Coefficients/(Std. Err) | Coefficients/(Std. Err) | Coefficients/(Std. Err) | Coefficients/(Std. Err) | ||||||||

| Intercept | 2.132 * | 1.936 * | 1.892 * | 2.006 * | 2.157 * | 2.118 * | 2.133 * | 2.027 * | 2.283 * | 2.079 * | 2.243 * | 2.139 * |

| (−0.003) | (−0.003) | (−0.003) | (−0.002) | (−0.011) | (−0.009) | (−0.006) | (−0.005) | (−0.004) | (−0.004) | (−0.005) | (−0.004) | |

| Income deprivation | 0.358 * | 0.448 * | 0.261 * | 0.164 * | 0.74 * | 0.357 * | 0.466 * | 0.113 | 0.433 * | 0.374 * | 0.043 | 0.011 |

| (−0.024) | (−0.026) | (−0.024) | (−0.024) | (−0.084) | (−0.079) | (−0.051) | (−0.047) | (−0.035) | (−0.037) | (−0.038) | (−0.038) | |

| Squared income deprivation | 0.453 * | 0.435 * | 0.548 * | 0.554 * | −1.159 | −0.128 | −0.988 * | −0.139 | −0.586 * | −0.788 * | −0.058 | −0.246 |

| (−0.105) | (−0.126) | (−0.119) | (0.151) | (−0.588) | (−0.886) | (−0.269) | (−0.308) | (−0.12) | (−0.184) | (−0.176) | (−0.332) | |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.085 | 0.092 | 0.05 | 0.022 | 0.14 | 0.043 | 0.265 | 0.026 | 0.139 | 0.083 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Sample size | 6505 | 6505 | 6505 | 6505 | 461 | 461 | 265 | 265 | 1398 | 1398 | 772 | 772 |

| Variables | Minimum | Lower Quartile (25%) | Median (50%) | Upper Quartile (75%) | Maximum | Non-Stationarity Test (F Statistic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.701 | 2.065 | 2.192 | 2.282 | 2.504 | 516.3 * |

| Income deprivation | −0.248 | 0.039 | 0.169 | 0.342 | 1.044 | 11.81 * |

| Squared Income Deprivation | −1.884 | −0.721 | −0.239 | 0.240 | 8.324 | 5.87 * |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.827 | |||||

| Residual standard error | 0.075 | |||||

| 2012 | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.663 | 1.968 | 2.047 | 2.123 | 2.262 | 383 * |

| Income deprivation | −0.28 | 0.020 | 0.154 | 0.249 | 1.409 | 7.52 * |

| Squared Income Deprivation | −5.508 | −1.078 | −0.562 | −0.026 | 14.25 | 5.49 * |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.791 | |||||

| Residual standard error | 0.068 | |||||

| Models | RSS | DF | MS | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | |||||

| OLS (2004) | 194.5 | 6502 | 0.03 | ||

| GWR | 35.8 | 6336 | 0.006 | ||

| GWR improvement | 158.7 | 165.7 | 0.958 | 169.7 | 0.000 |

| 2012 | |||||

| OLS (2012) | 141.2 | 6502 | 0.022 | ||

| GWR | 29.4 | 6332 | 0.005 | ||

| GWR improvement | 111.8 | 169.8 | 0.659 | 142.1 | 0.000 |

| Clusters | Cluster Summaries | Income Deprivation Summaries | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income Deprivation | Squared Income Deprivation | Cluster Size | Median | Min | Max | |

| 2004 | Coefficients | |||||

| cluster 1 | 0.19 | −0.48 | 2486 | 0.12 | −0.15 | 0.66 |

| cluster 2 | 0.52 | −1.02 | 1377 | 0.08 | −0.15 | 0.46 |

| cluster 3 | 0.33 | 2.61 | 308 | 0.10 | −0.14 | 0.19 |

| cluster 4 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 2334 | 0.14 | −0.15 | 0.55 |

| 2012 | Coefficients | |||||

| cluster 1 | 0.16 | −0.92 | 3008 | 0.12 | −0.14 | 0.44 |

| cluster 2 | 0.41 | −0.95 | 1324 | 0.08 | −0.13 | 0.34 |

| cluster 3 | 0.08 | 5.08 | 164 | 0.09 | −0.13 | 0.15 |

| cluster 4 | −0.01 | 0.11 | 2009 | 0.14 | −0.14 | 0.51 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bailey, N.; Dong, G.; Minton, J.; Pryce, G. Reconsidering the Relationship between Air Pollution and Deprivation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040629

Bailey N, Dong G, Minton J, Pryce G. Reconsidering the Relationship between Air Pollution and Deprivation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(4):629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040629

Chicago/Turabian StyleBailey, Nick, Guanpeng Dong, Jon Minton, and Gwilym Pryce. 2018. "Reconsidering the Relationship between Air Pollution and Deprivation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 4: 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040629

APA StyleBailey, N., Dong, G., Minton, J., & Pryce, G. (2018). Reconsidering the Relationship between Air Pollution and Deprivation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(4), 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040629