Working towards More Effective Implementation, Dissemination and Scale-Up of Lower-Limb Injury-Prevention Programs: Insights from Community Australian Football Coaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

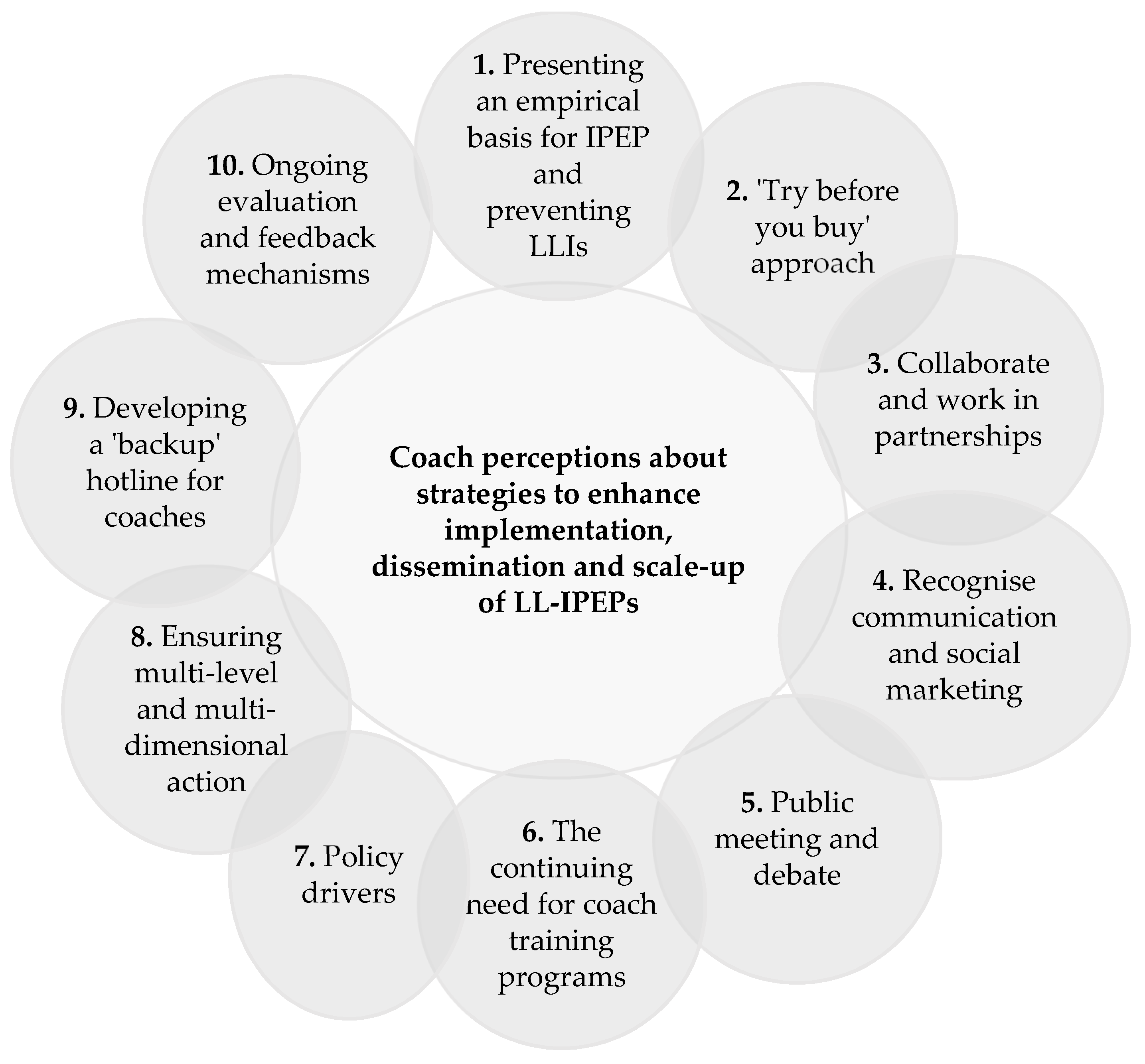

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Presenting an Empirical Basis for Injury-Prevention Exercise Programs and Preventing Lower-Limb Injuries Getting the Facts

If a program was presented to me at a seminar, and the one thing I said to … that I asked the … (Victoria Project Manager), initially (prior to the program trial), was ‘is there any statistics yet that it does (LL-IPEP) prevent injury?’ I couldn’t see that it was going to be detrimental to the players’ warm-up, but I think statistical data, which could be provided within a seminar … or a handout that shows … from this program the injury rates were reduced in comparison to X is important. I think figures hit home a lot harder than necessarily saying the proof’s in the pudding … this will change or this will help … has it been proven, and why will it help? … I can certainly see the benefits, and …I think statistics have bigger impact than necessarily a program per se. Somebody sits down and goes wow, they can show that injury prevention in knees, ankles … were reduced by 35 per cent. Why? Because of the training implementation, that also increased players’ attendance on the track, by another rate of 25 per cent, through the maintenance component. The injury-prevention element of it, I think that’s going to sink into potential coaches, or people at the seminar a lot more than the program itself. I’ll go home and analyse the program anyway, but …you also don’t want to leave it to (a coach’s) own interpretation of whether they think it’s going to be beneficial, you need some fairly substantial supporting data with it, which I think, just tops off the presentation. It provides you with a reason, why should you, how come I’m doing this? Now that I know about it, it can only benefit, because these statistics prove. And as I said, you can tailor other stats like you want, but ultimately, there only has to be two, three or four reasons as to why it benefits the playing group, or the players, and coaches will look at it and say, I’ve got to incorporate that.(Brian)

I’m eagerly awaiting what’s coming out (evidence) because I’ll actually use that as a basis for my teaching. …I teach fitness instructors, I teach Year 12 P.E. (Physical Education). They’re … the people, the next generation, that’s going to use this information. So, from my own professional side of things, I’m waiting for those studies to come down (evidence of study findings to be disseminated). From the coaching side of things, once again, because I can interpret it, I probably will go back out into coaching in some way, shape or form in the next couple of years, so when those studies are there, I’ll probably use it as part of my own periodization throughout the design and warm-ups and cool downs based on it because I do see the benefit at the start and the finish of these programs.(Geoff)

3.2. ‘Try before You Buy’ Approach

I had no issues with it at all. I thought it was great. It was well run and everything was fine. It was an opportunity to get new insights. It’s probably tough as well ‘cos I’ve only seen it for that one year so I’ve only really got that to work off (and) if I got to see a comparison … Seeing it run again in a different environment, I could probably have a bit more of an idea of how I could implement it and what might work best in different environments.(Andrew)

3.3. Collaborate and Work in Partnership

I think there’s ways to get to Football Victoria, the VCFL (Victorian Country Football League), the AFL (Australian Football League), they’re the football bodies that you need to start getting support from, then can deliver that to the leagues, as such, as each league is answerable to their operations. That would be the initial starting point, I think that’s probably the most feasible way to do it, getting leagues together. I think that’s the most achievable, successful way to implement it.(Brian)

3.4. Recognising Communication and Social Marketing

I initially knew about the program from the newspaper and saw it on the local news. I also had contact with a few uni. (University) students who knew what was going on with the program, but also basically through a lot of reading about these types of programs. In the previous year, in one of the clubs where the program had been trialed, I spoke to a few players from there. It was part of professional development for me just reading about what the prevention measures for injuries were, so I was always up to date with the background. I did have awareness of the potential benefits of such programs … I jumped at the chance to be involved.(Geoff)

Social marketing may be applicable for preparing and stimulating coaches (and others) who may be contemplating change [53]. Geoff’s experience in observing media about the IPEP triggered his interest and he seemed to have no hesitation in later making the decision to agree to trial the program with his team of players in the following season. He was highly intrinsically motivated, ‘I jumped at the chance to be involved’.(Geoff)

… marketing, yeah, is probably a big one. There’s probably no point–if you don’t have some people to endorse it that are pretty big in it. Even some footballers, you know, well known footballers, that sort of thing, to say that this is the way that football is going, prevention and that sort of thing and if you want the best out of your players.(Andrew)

… our main focus is to have a full list every week to pick from because sides that win Premierships have good depth, they have players to fill spots when players are out. So, if you haven’t got a good side coming up behind you, like in Reserves - If you look back for years, you’ll find that the Reserve sides either played in the Premiership or won it with them. So, if you’ve got those two well balanced, and good sides, good players to be able to fill holes … If you have this side at the start of the year and you hopefully don’t lose anyone by the end of it … if you can keep them on the park and not have any major injuries like broken bones and that sort of thing, you can have a fair crack at the year. So, when you go out and recruit players, you go out and recruit a side. You don’t go out and recruit a side plus extras in case there’s an injury. You go and pick that side that you think is going to win a Premiership.(Andrew)

Understanding the coach’s character and highlighting the importance of the program was found to be especially important. Preventing injuries and thereby reducing the number of injured players means that the coach will have more players available for his/her ideal team. Therefore, it is not only information and education about the role of injury prevention that is important, but also speaking the same language as the coach (p. 805).

Probably the information’s always a big one … We’re pretty visual and we like to see some results before taking it on … So, if we had some good stats (statistics) on that side of things … you know … if there is some time spent on creating material it’s actually ‘gonna’ work, and continue to send information out there over time. That would be a big thing.(Andrew)

3.5. Public Meeting and Debate

The easiest way to deliver it would be to hold a general (or public) meeting, and you’d need to deliver it to coaches, presidents, football managers … get all the key people at the club/s. You can’t invite whole committees to a meeting as such, but you can get the president, the football manager, all coaches, from the U18s, seniors, reserves and juniors—if you’re wanting to go through junior clubs.(Brian)

The easiest way is to get it in a seminar environment, so if you’re talking about the Ballarat Football League as an example–they’re affiliated with three leagues–the Ballarat Football League, the Central Highlands League, and the Maryborough Football League. Not all leagues are fortunate enough to have the facility (governance) that they control all three.(Brian)

In a large meeting/seminar you could get representatives to present programs (IPEPs) and information on related topics. Handouts could be provided about the program. You could go through the information and have the program packaged to take away, it would have probably been enough for me to then go away and implement it.(Brian)

The program (IPEP), when it was presented to me, provided the resources of two girls (IPEP trainers) who were going to come and run the program. So there are different ways that it could be delivered and this strategy could be discussed (e.g., direct or indirect approach) … I think that it’s got to be a fairly in-depth seminar that talks about each stage (of IPEP integration, delivery and maintenance in the long term) so that people in the seminar understand. Some people that are football coaches, they’re going to have a better understanding of the … or jargon, with regards to what we are talking about, with exercise or limbs or stretches or implementation of what your trying to do, than compared to … maybe someone who may still have even a level one coaching accreditation. So, it’s having that sort of open forum, and delivering it to everyone, you can’t send everyone from every football club, it’s not feasible, and it’s not achievable. You’ve got to hope that the information delivered is attainable and explainable, for the people that take it away, or the environment is open enough that people feel comfortable to ask the questions that are necessary. At least have a ‘Q and A’ afterwards, where those embarrassed, or quieter people can come up to one or two people who are doing the seminar to do so.(Brian)

Having such a meeting at separate football clubs might be an option. It’s more personal, and implementation could quite possibly be more successful, because people will feel more comfortable asking questions in a one-on-one environment, than they would in a three-league environment.(Brian)

3.6. The Continuing Need for Coach Training Programs

3.6.1. Formal Learning

There’s hundreds and hundreds of coaches a year, that perform a level one or level two coaching accreditation, where if you can get the program, not authorized, but approved upon, and have the VFL, AFL or league level, or whoever runs the coach accreditations, to support the program (IPEPs). They (the AFLCA) get guest speakers in, and they get football tacticians, they get the support, they get the fitness advisors, or maybe you can get yourself into an hours presentation to a level one or two coaching course accreditation, and then you start to hit the coaches at that level as well. … if you can get them to approve, then you are going to be hitting another level of coaches each year.(Brian)

3.6.2. Non-Formal - Seminars and Workshops

Well, I think from a coaches’ point of view, just generally speaking, that this sort of thing could be organized … maybe at the end of the year, you know, before pre-season starts as a refresher and going through these sorts of the things (the IPEP) at a coaches’ forum would be fantastic.(Geoff)

I think it’s just a part of coaching. It’s like going to any coaching seminar, I think. Yeah, so I think they could … Like they do a coaching seminar at the end of every year for new coaches that want to do this level of accreditation (Level 2), so I think that would be a good day to do something like the IPEP … that focuses on the injury sort of stuff as well. To try to work in with that too.(Andrew)

I know I can implement these things because I’m still involved in the industry (sport and exercise science) but for a general coach, having them or educating them at the start of the season is too late. I would say probably early November would be perfect because a lot of teams start to train again in about November. So, that would probably be the perfect time because if they are doing it right, they’re setting out (planning) their programs (or training schedules). They get this program (IPEPs), they get some ideas and they’d be able to run with it.(Geoff)

So, I think that would be an ongoing one (the forum). They (coaches) just need to get constant reinforcement. If it’s put in front of them as a good idea, and it’s in their face, they will use it. If it’s something that you do every three years, they’ll do it for 6 months, 12 months. The second year and the third year, they’ll forget it. Once they get the refresher … ‘oh yeah that was a good idea, bring it back in’. Obviously, the costs’ there, it’s the personnel just going through it. You’re trying to train up coaches. Or their assistant coaches or staff that they’ve got there. But ongoing development for those people would be fantastic.(Geoff)

3.7. Policy Drivers

Well, I’ve seen a lot of changes and it wouldn’t be a bad thing and it would surprise me if it happens. I think it would be good. I would definitely be an advocate for it but … I’ve seen a lot of changes over 10 years where injuries and the improved awareness and that’s great … that we are in much better position than what we were 10 years ago, that’s for sure. Injuries 10 years ago, where a player might never play again and something from a simple knee clean out. Knee rehabs these days–you know, one of the guys in Ballarat had the keyhole surgery on the knee and was back in seven weeks. Like that Sydney guy, Malcheski or whatever his name was, had (new intervention for injury). So, those sort of advances I’ve talked about, and … the potential for policy in injury prevention are great.(Andrew)

The policy side of things is always going to be difficult … Because leagues have different constitutions. You need to go through the VCFL, the Metro and Amateurs boards and go through trying to implement it through those people. The AFL overseas everything, they’re obviously the peak body but they delegate quite a lot. For my club, it’s the VCFL. For Essendon districts it’s the Metropolitan Football League. And then you’ve got the amateur association. So, there are three bodies that you’d need to go through.(Geoff)

3.8. Ensuring Multi-Level and Multi-Dimensional Action

That’s where the—if you had it built into the accreditation process, it will keep going. Once something is in a club, the harder it is to get it out. Each coach that is coming in (that is. a new coach transitioning into a club) might have their ideas, but players will say nuh (no) we do this. I had a number of drills, ‘oh we call it this, we did this process or that’s what we used to do with this other coach’. They know, they remember. Players remember. So, they will all suggest it, and when a club brings in a new coach, generally that coach will have a designated person to help mentor them within the club. So if it’s a part of what is working and the clubs accepted, yes, this is what we want to do, it should not fade out. It’s only when you get those massive whole-board changes; the coaching staff changes, that’s when you might lose the program. But for a general club to club, it may change slightly. Aspects of the program might change or the time given might change slightly but the elements will still be there.(Geoff)

3.9. Developing a Backup ‘Hotline’ for Coaches

I think having a contact, some sort of hotline to call would be helpful. If I get a program like that (the IPEPs), first thing I’d say is where has it come from? Who am I going to speak to? If I was going to coach, next year and the year after that, I want to know more. So, who’s the person I can contact? Is there someone, a point of contact or a helpline I can use? Somewhere that I can call, or someone to contact to talk to about at any stage, this would be great.(Brian)

3.10. Ongoing Evaluation and Feedback Mechanisms

I think ongoing data attention to injury reporting and other aspects (performance) would be useful and supportive, ongoing collation of data and any extensions to the program would be something I would be looking for … I am one of those coaches who like to evolve and knows what going on.(Brian)

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Klugl, M.; Shrier, I.; McBain, K.; Shultz, R.; Meeuwisse, W.H.; Garza, D.; Matheson, G.O. The prevention of sport injury: An analysis of 12,000 published manuscripts. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2010, 20, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew, N.; Gabbe, B.; Cook, J.; Lloyd, D.G.; Donnelly, C.J.; Nash, C.; Finch, C.F. Could targeted exercise programmes prevent lower limb injury in community australian football? Sports Med. 2013, 43, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGlashan, A.J.; Finch, C.F. The extent to which behavioural and social sciences theories and models are used in sport injury prevention research. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 841–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffen, K.; Meewisse, W.H.; Romiti, M.; Kang, J.; McKay, C.; Bizzini, M.; Dvirak, J.; Finch, C.; Mykelbust, G.; Emery, C. Evaluation of how different implementation strategies of an injury prevention programme (FIFA 11+) impact team adherence and injury risk in canadian female youth football players: A clustered-randomised trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahr, R.; Thorborg, K.; Ekstrand, J. Evidence-based hamstring injury prevention is not adopted by the majority of champions league or norwegian premier league football teams: The nordic hamstring survey. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 1466–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quarrie, K.L.; Gianotti, S.M.; Hopkins, W.G.; Hume, P.A. Effect of nationwide injury prevention programme on serious spinal injuries in new zealand rugby union: Ecological study. BMJ 2007, 334, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dick, R.; Goulet, C.; Gianotti, S. Implementing large-scale injury prevention programs. In Sports Injury Prevention; Bahr, R., Engebresten, L., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, L.; Parcel, G.; Kok, G.; Gottlieb, N. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen, E.; Finch, C. Setting our minds to implementation. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 1015–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viljoen, W.; Patricios, J. Boksmart-implementing a national rugby safety programme. Br. J. Sports Med. 2012, 46, 692–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizzini, M.; Junge, A.; Dvorak, J.; Dvorak, J. Implementing of the FIFA 11+ football warm up program: How to approach and convince the football associations to invest in prevention. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 803–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myklebust, G.; Skjolberg, A.; Bahr, R. ACL injury incidence in female handball 10 years after the norwegian ACL prevention study: Important lessons learned. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 476–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindblom, H.; Walden, M.; Carlfjord, S.; Haggland, M. Implementation of a neuromuscular training programme in female adolescent football: 3-year follow-up study after a randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 1425–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, A.; Lloyd, D.G.; Gabbe, B.J.; Cook, J.; Finch, C.F. We have the programme, what next? Planning the implementation of an injury prevention programme. Inj. Prev. 2017, 23, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Providenza, C.; Engebretsen, L.; Tator, C.; Kissick, J.; McCrory, P.; Sills, A.; Johnston, K.M. From consensus to action: Knowledge transfer, education and influencing policy on sports concussion. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finch, C. A new framework for research leading to sports injury prevention. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2006, 9, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klesges, L.M.; Estabrooks, P.A.; Dzewaltowski, D.A.; Bull, S.S.; Glasgow, R.E. Beginning with the application in mind: Designing and planning health behavior change interventions to enhance dissemination. Ann. Behav. Med. 2005, 29, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milat, A.J.; Bauman, A.; Redman, S. Narrative review of models and success factors for scaling up public health interventions. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milat, A.J.; King, L.; Newson, R.; Wolfenden, L.; Rissel, C.; Bauman, A.; Redman, S. Increasing the scale and adoption of population health interventions: Experiences and perspectives of policy makers, practitioners, and researchers. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2014, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, D.; Allegrante, J.P.; Sleet, D.; Finch, C.F. Editorial: Research alone is not sufficient to prevent sports injury. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 682–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talpey, S.W.; Siesmaa, E.J. Sports injury prevention: The role of the strength and conditioning coach. Strength Cond. J. 2017, 39, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlashan, A.J. Enhancing Integration of Specialised Exercise Training into Coach Practice to Prevent Lower Limb Injury: Using Theory and Exploring Coaches’ Salient Beliefs; Federation University: Ballarat, VIC, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, C.; Gabbe, B.; White, P.; Lloyd, D.; Twomey, D.; Donaldson, A.; Elliott, B.; Cook, J. Priorities for investment in injury prevention in community australian football. Clin. J. Sports Med. 2013, 23, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheson, G.O.; Klugl, M.; Dvorak, J.; Engebretsen, L.; Meeuwisse, W.H.; Schwellnus, M.; Blair, S.N.; van Mechelen, W.; Derman, W.; Borjesson, M.; et al. Responsibility of sport and exercise medicine in preventing and managing chronic disease: Applying our knowledge and skill is overdue. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 1272–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stake, R.E. Case studies. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 435–453. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Methods Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Reade, I.; Rodger, W.; Spriggs, K. New ideas and high performance coaches: A case study of knowledge transfer in sport science. Int. J. Sport Sci. Coach. 2008, 360, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendellen, K.; Camiré, M.; Bean, C.N.; Forneris, T.; Thompson, J. Integrating life skills into golf Canada’s youth programs: Insights into a successful research to practice partnership. J. Sport Psychol. Action 2017, 8, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Enquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, C.F.; Doyle, T.L.; Dempsey, A.R.; Elliott, B.C.; Twomey, D.M.; White, P.E.; Diamantopoulos, K.; Young, W.; Lloyd, D.G. What do community football players think about different exercise training programmes? Implications for the delivery of lower limb injury prevention programmes. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finch, C.F.; Twomey, D.M.; Fortington, L.V.; Doyle, T.L.; Elliott, B.C.; Akram, M.; Lloyd, D.G. Preventing australian football injuries with a targeted neuromuscular control exercise programme: Comparative injury rates from a training intervention delivered in a clustered randomised controlled trial. Inj. Prev. 2016, 22, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finch, C.; Lloyd, D.; Elliott, B. The preventing Australian football injuries with exercise (pafix) study: A group randomised controlled trial. Inj. Prev. 2009, 15, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qualitative, S.; Research, I. Nvivo (Version 9.0); Qualitative Solution and Research International: Doncaster, VIC, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes, A.C. Developing mixed methods research in sport and exercise psychology: Critical reflections on five points of controversy. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.J.; Kendall, L. Perceptions of elite coaches and sport scientists of the research needs for elite coaching practice. J. Sports Sci. 2007, 25, 1577–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Gielen, A.C.; Sleet, D.; Green, L.W. Community models and approaches to interventions. In Injury and Violence Prevention: Behavioral Science Theories, Methods, and Applications; Gielen, A.C., Sleet, D., DiClemente, R.J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, A.; Poulas, R.G. Planning the diffusion of a neck-injury prevention programme among community rugby union coaches. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, A.; Finch, C.F. Editorial: Applying implementation science to sport injury prevention. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegrante, J.P.; Hanson, D.W.; Sleet, D.A.; Marks, R. Ecological approaches to the prevention of unintentional injuries. Ital. J. Public Health 2010, 7, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, R.; Phillips, R.; Tillbrook, R.; Lowe, K. Middle-out approaches to reform of university teaching and learning: Champions striding between the “top-down” and “bottom-up” approaches. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distance Learn. 2005, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, V.; Hart, K. Getting the message out-disseminating research findings to employees in large rural mining organisations. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 30, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter, M.; Lezin, N.; Young, L. Evaluating community-based collaborative mechanisms: Implications for practitioners. Health Promot. Pract. 2000, 1, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakocs, R.C.; Edwards, E.M. What explains community coalition effectiveness? A review of the literature. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 30, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VicHealth. The Partnership Analysis Tool. Available online: https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/media-and-resources/publications/the-partnerships-analysis-tool (accessed on 15 January 2015).

- Bauman, A.E.; Nelson, D.E.; Pratt, M.; Matsudo, V.K.R.; Schoeppe, S. Dissemination of physical activity evidence, programs, policies, and surveliiance in the international public health arena. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 31, S57–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, J.; Ewing, M.; Finch, C. Social marketing: Why injury prevention needs to adopt this behaviour change approach. Br. J. Sports Med. 2012, 47, 665–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estabrooks, P.A.; Glasgow, R.E. Translating effective clinical-based physical activity intervention into practice. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 31, S45–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storey, J.D.; Saffitz, G.B.; Rimon, J.G. Social marketing. In Health Behavior and Health Education; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Viswanath, K., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 4, pp. 435–461. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen, A. Social marketing: Definition and domain. J. Public Policy Mark. 1994, 13, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Redding, C.A.; Evers, K.E. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Lewis, F.M., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002; Volume 3, pp. 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, E.B.; Ramsey, L.T.; Brownson, R.C.; Heath, G.W.; Howze, E.H.; Powell, K.E.; Stone, E.J.; Rajab, M.W.; Corso, P. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity: A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 22, 73–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearing, J.W.; Maibach, E.W.; Buller, D.B. A convergent diffusion and social marketing approach for disseminating proven approaches to physical activity intervention. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 31, S11–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizzini, M.; Dvorak, J. Fifa 11+: An effective programme to prevent football injuries in various player groups worldwide—A narrative review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, D.; Liaw, S.T.; Dobell, J.; Anderson, R. Australian rural football club leaders as mental health advocates: An investigation of the impact of the coach the coach project. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2010, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action; Prentice-Hall: Englewood-Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock, I.M.; Strecher, V.J.; Becker, M.H. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Mechelen, D.M.; van Mechelen, W.; Verhagen, E.A.L.M. Sport injury prevention in your pocket?! Prevention apps assessed against the available scientific evidence: A review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 878–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gielen, A.C.; Girasek, D.C. Integrating perspectives on the prevention of unintentional injuries. In Integrating Behvaioural and Social Sciences with Public Health; Schneiderman, N., Speers, M.A., Silva, J.M., Tomes, H., Gentry, J.H., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 203–230. [Google Scholar]

- Straus, D.A. Managing meetings to build consensus. In The Consensis Building Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide to Reaching Agreement; Susskind, S., McKearnen, S., Thomas-Lamar, J., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 287–322. [Google Scholar]

- Heaney, C.A.; Walker, N.C.; Green, A.J.K.; Rostron, C.L. Sport psychology education for sport injury rehabilitation professionals: A systematic review. Phys. Ther. Sport 2015, 16, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemyre, F.; Trudel, P.; Durand-Bush, N. How youth-sport coaches learn to coach? Sport Psychol. 2007, 21, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushion, C.; Nelson, L.; Armour, K.; Lyle, J.; Jones, R.; Sandford, R.; O’Callaghan, C. Coach Learning and Development: A Review of the Literature; The National Coaching Foundation: Leeds, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Woodman, L. AFL Coaching Registrations; AFL Coaches Association: Brighton, VIC, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Football League Coaches Association. The 2013 Coach Manual; AFL: Duncan, BC, Canada, 2013; Volume 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mallett, C.J.; Rossi, T.; Tinning, R. Coaching Knowledge, Learning and Mentoring in the AFL; University of Queensland: Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Junge, A.; Lamprecht, M.; Stamm, H.; Hasler, H.; Bizzini, M.; Tschopp, M.; Reuter, H.; Wyss, H.; Chilvers, C.; Dvorak, J. Countrywide campaign to prevent soccer injuries in swiss amateur players. Am. J. Sports Med. 2011, 39, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Vogt, T.M.; Boles, S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The re-aim framework. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasgow, R.E.; McKay, H.G.; Piette, J.D.; Reynolds, K.D. The re-aim framework for evaluating interventions: What can it tell us about approaches to chronic illness management. Patient Educ. Couns. 2001, 44, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, B.A.; Brownson, R.C.; Kerner, J.F.; Glasgow, R.E. Methodological challenges in disseminating evidence-base interventions to promote physical activity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 31, S24–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, C.; Sproule, J. Coaches perceptions of coach education experiences. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2012, 43, 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, G.A.; Durand Bush, N.; Schnicke, R.J.; Salmela, J.H. The importance of mentoring in the development of coaches and athletes. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 1998, 29, 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.; Armour, K.; Potrac, P. Constructing expert knowledge: A case study of a top-level professional soccer coach. Sport Educ. Soc. 2003, 8, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.; Trudel, P.; Culver, D. Learning how to coach: The different learning situations reported by youth ice hockey coaches. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2007, 12, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushion, C.; Armour, K.; Jones, R. Coach education and continuing professional development: Experience and learning to coach. Quest 2003, 55, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, T.; Potrac, P.; McKenzie, A. Evaluating and reflecting upon a coach education initiative: The code of rugby. Sport Psychol. 2006, 20, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, T.; Jones, R.L.; Potrac, P. Understanding Sports Coaching: The Social, Cultural and Pedagogical Foundations of Coaching Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Football League. Australian Football League (AFL) Policies; AFL: Duncan, BC, Canada, 2014; Volume 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Football League: Community. Australian Football League (AFL) Policy and Guidelines. Available online: http://www.aflcommunityclub.com.au/index.php?id=211 (accessed on 10 November 2014).

- Donaldson, A.; Leggett, S.; Finch, C.F. Sports policy development and implementation in context: Researching and understanding the perceptions of community end-users. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2012, 47, 743–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, C.F.; Donaldson, A. A sports setting matrix for understanding the implementation context for community sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, J.; Chalmers, D.; Waller, A. The New Zealand rugby injury and performance project: Developing ‘tackling rugby injury’, a national injury prevention program. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2002, 13, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fortington, L.V.; Finch, C.F. Priorities for injury prevention in women’s australian football: A compilation of national data from different sources. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2016, 2, e000101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gielen, A.C. Application of behavior-change theories and methods to injury prevention. Epidemiol. Rev. 2003, 25, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, K. The need for, and value of, a multi-level approach to disease prevention: The case of tobacco control. In Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioural Research; Smedley, B.D., Syme, S.L., Eds.; National Academics Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Green, L.W.; Orleans, C.T.; Ottoson, J.M.; Cameron, R.; Pierce, J.P.; Bettinghaus, E.P. Inferring strategies for disseminating physical activity policies, programs and practices from the successes of tobacco control. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 31, S66–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittlemark, M.B.; Wise, M.; Nam, E.W.; Santos, B.C.; Fosse, E.; Saan, H.; Hagard, S.; Tang, K.G. Mapping national capacity to engage in health promotion: Overview of issues and approaches. Health Promot. Int. 2006, 21, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timpka, T.; Eckstrand, J.; Svanstrom, L. From sports injury prevention to safety promotion in sports. Sports Med. 2006, 36, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timpka, T.; Finch, C.F.; Goulet, C.; Noakes, T.; Yammine, K. Meeting the global demand of sports safety: The intersection of science and policy in sport safety. Sports Med. 2008, 38, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, N.; Otago, L.; Romiti, M.; Donaldson, A.; Finch, C. Coaches’ perspective on implementing an evidence-informed injury prevention programme in junior community netball. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, 1128–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, B.S.; Register-Mihalik, J.; Padua, D.A. High levels of coach intent to integrate a ACL injury prevention program into training does not translate to effective implementation. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2015, 18, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulos, R.G.; Donaldson, A. Improving the diffusion of safety initiatives in community sport. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2015, 18, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, L.J.; Cushion, C. Reflection in coach education: The case of the national governing body coaching certificate. Sport Psychol. 2006, 20, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, J.P.; Stewart, N.W.; Law, B.; Hall, C.R.; Gregg, M.J.; Robertson, R. Knowledge translation of sport psychology to coaches: Coaches’ use of online resources. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2015, 10, 1055–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CoachAssist. Available online: http://www.coachassist.com.au/default.aspx (accessed on 10 October 2014).

- League, A.F. Australian Football League: Community. Available online: http://www.aflcommunityclub.com.au/ (accessed on 10 October 2014).

- Embling, M. Coaching and the Internet. Available online: http://www.aflcommunityclub.com.au/index.php?id=47&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=3406&cHash=fc4dca31b488b980cb65155a8ff249ba (accessed on 4 May 2015).

- Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N. Ecological models of health behavior. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Lewis, F.M., Eds.; John Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002; Volume 3, pp. 462–484. [Google Scholar]

- Allegrante, J.P.; Marks, R.; Hanson, D.W. Ecological models for the prevention and control of unintentional injury. In Injury and Violence Prevention: Behavioural Science Theories, Methods and Applications; Gielen, A.C., Sleet, D.A., DiClemente, R.J., Eds.; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 105–126. [Google Scholar]

- LaVoi, N.M.; Dutove, J.K. Barriers and supports for female coaches: An ecological model. Sports Coach. Rev. 2012, 1, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, D.; Hall, M.; Howat, P. Using theory to guide practice in children’s pedestrain safety education. Am. J. Health Stud. 2003, 34, S42–S47. [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen, E.; van Mechelen, W. Editorial: Sport for all, injury prevention for all. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finch, C. Implementation and dissemination research: The time has come. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 763–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhagen, E.; Vriend, I. Preventing ankle sprains with a smartphone: Implementation effectiveness of an evidence based app. In Proceedings of the 2013 Asics Conference of Science and Medicine in Sport, Phuket, Thailand, 23–25 October 2013; Volume 16 (Suppl.1), p. e25. [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen, E.; van Stralen, M.M.; Maartje, M.; van Mechelen, W. Behaviour, the key factor for injury prevention. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McGlashan, A.; Verrinder, G.; Verhagen, E. Working towards More Effective Implementation, Dissemination and Scale-Up of Lower-Limb Injury-Prevention Programs: Insights from Community Australian Football Coaches. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020351

McGlashan A, Verrinder G, Verhagen E. Working towards More Effective Implementation, Dissemination and Scale-Up of Lower-Limb Injury-Prevention Programs: Insights from Community Australian Football Coaches. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(2):351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020351

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcGlashan, Angela, Glenda Verrinder, and Evert Verhagen. 2018. "Working towards More Effective Implementation, Dissemination and Scale-Up of Lower-Limb Injury-Prevention Programs: Insights from Community Australian Football Coaches" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 2: 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020351

APA StyleMcGlashan, A., Verrinder, G., & Verhagen, E. (2018). Working towards More Effective Implementation, Dissemination and Scale-Up of Lower-Limb Injury-Prevention Programs: Insights from Community Australian Football Coaches. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(2), 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020351