Characteristics of Stress and Suicidal Ideation in the Disclosure of Sexual Orientation among Young French LGB Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Emotions

- −

- “Well-being” (23.07% of explained variance) included six emotions (amused, reassured, satisfied, happy, hopeful, relieved).

- −

- “Hostility and disappointment” (14.96% of explained variance) included six emotions (angry, sad, disappointed, offended, disgusted, frustrated).

- −

- “Anxious anticipation” (9.91% of explained variance) included six emotions (preoccupied, threatened, scared, guilty, anxious, embarrassed).

- −

- “Mastery” (5.38% of explained variance) included three emotions (combative, confident, master of myself).

- −

- “Jealousy” (4.66% of explained variance) included two emotions (jealous, envious).

- −

- “Well-being and mastery (At the end, two initials factors (well-being and mastery) are grouped as a single factor)” (38.57% of explained variance) included nine emotions (amused, reassured, satisfied, happy, hopeful, relieved, combative, confident, master of myself).

- −

- “Hostility and disappointment” (13.46% of variation explained) included six emotions (angry, sad, disappointed, offended, disgusted, frustrated).

- −

- “Anxious anticipation” (5.88% of variation explained) included six emotions (preoccupied, threatened, scared, guilty, anxious, embarrassed).

- −

- “Jealousy” (5.14% of variation explained) included two emotions (jealous, envious).

2.3.2. Cognitive Appraisals

- −

- Risk 1 “Loss of respect and affection” (25.49% of explained variance) included three items: “Lose the affection of someone who is important to you”; “Lose the approval or respect of someone who is important to you”; “Lose respect for someone else”.

- −

- Risk 2 “Appear as a careless, unethical person” (12.94% of explained variance) included two items: “Appear as a careless person”; “Appear as an unethical person”.

- −

- Risk 3 “Incompetence and failure” (9.94% of explained variance) included three items: “To not reach an important goal at work”; “Diminish your financial resources”; “Come across as incompetent”.

- −

- Risk 4 “Cause suffering” (8.86% of explained variance) included two items: “Harm the physical wellbeing and health of your relatives”; “Hurt a relative”.

- −

- Risk 5 “Harm myself or others” (7.94% of explained variance) included three items: “Jeopardize your own physical health”, your security or your wellbeing”; “Disrupt a relative’s habits”; “Lose your self-esteem”.

2.3.3. Coping

- −

- “Avoidance” (12.05% of explained variance) included twenty two items (items 3, 6, 9, 11, 12, 14, 21, 25, 28, 32, 33, 34, 35, 41, 44, 51, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 62).

- −

- “Positive development” (9.01% of explained variance) included ten items (items 15, 18, 20, 23, 29, 30, 37, 39, 47, 50).

- −

- “Seeking help” (4.09% of explained variance) included six items (items 8, 18, 31, 43, 46, 53).

- −

- “Preparation and escape” (3.64% of explained variance) included ten items (items 19, 26, 27, 36, 52, 58, 60, 63, 54, 67).

- −

- “Minimization” (3.21% of explained variance) included six items (items 13, 24, 54, 42, 45, 55).

- −

- “Problem solving” (2.99% of explained variance) included eight items (items 1, 2, 5, 10, 22, 61, 65, 66).

- −

- “Aggression” (2.95% of explained variance) included three items (items 17, 40, 48).

- −

- “Acceptance” (2.57% of explained variance) included five items (items 4, 7, 20, 34, 38).

2.3.4. Suicidal Ideation

2.4. Data Analysis

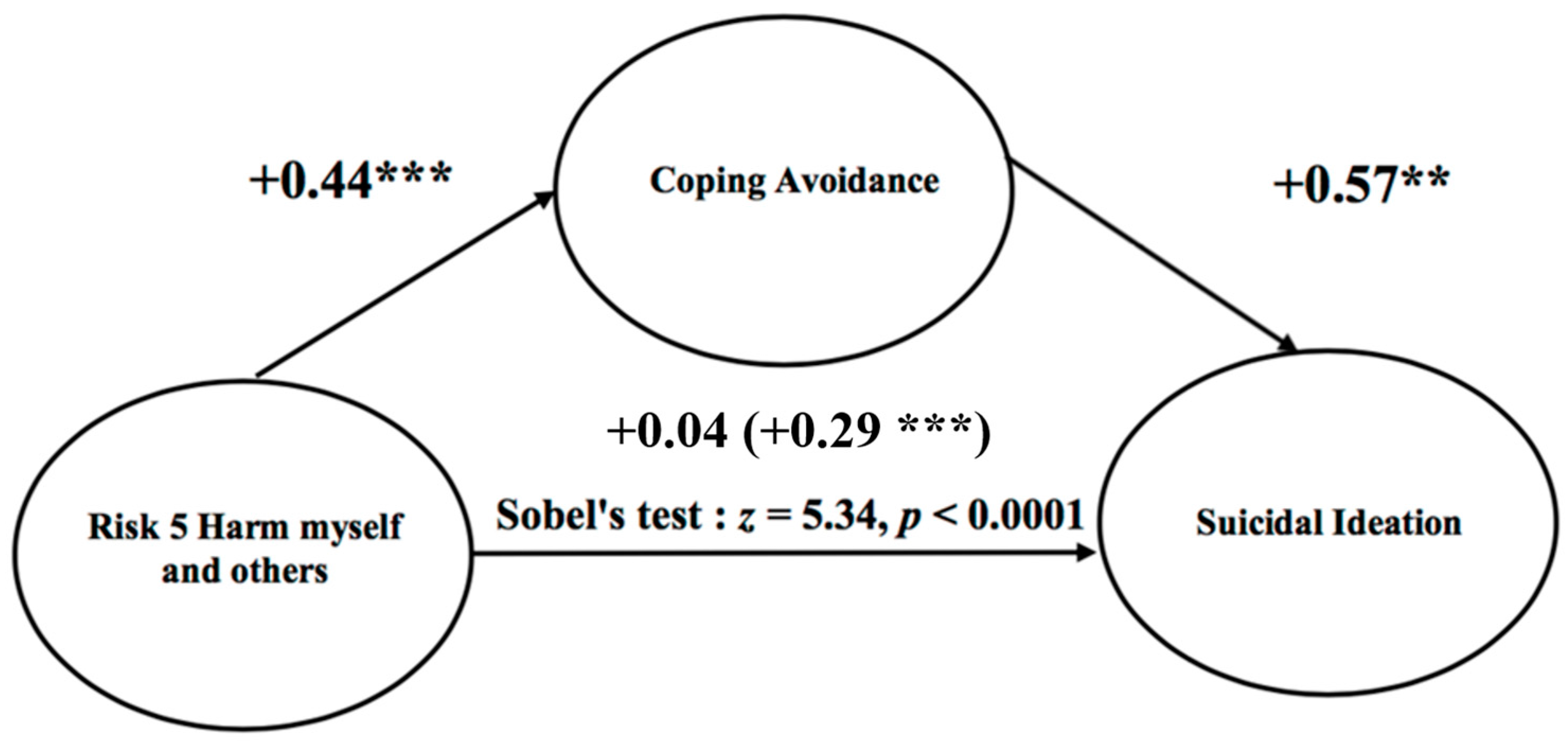

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Almazan, E.P.; Roettger, M.E.; Acosta, P.S. Measures of Sexual Minority Status and Suicide Risk among Young Adults in the United States. Arch. Suicide Res. 2014, 18, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.B.; Oxendine, S.; Taub, D.J.; Robertson, J. Suicide Prevention for LGBT Students. New Dir. Stud. Serv. 2013, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshal, M.P.; Dietz, L.J.; Friedman, M.S.; Stall, R.; Smith, H.A.; McGinley, J.; Thoma, B.C.; Murray, P.J.; D’Augelli, A.R.; Brent, D.A. Suicidality and Depression Disparities Between Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 49, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, S.; Joyner, K. Adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk: Evidence from a national study. Am. J. Public Health 2001, 91, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skerrett, D.; Kõlves, K.; Leo, D. De Are LGBT populations at a higher risk for suicidal behaviors in Australia? Research findings and implications. J. Homosex. 2015, 62, 883–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdet, S.; Pugnière, J.M. Attirance sexuelle, suicidalité et homophobie intériorisée. In Masculinité état des Lieux; Welzer-Lang, D., Ed.; Erès: Toulouse, France, 2011; pp. 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Jouvin, E.; Beaulieu-Prévost, D.; Julien, D. Minorités sexuelles: Des populations plus exposées que les autres? In Baromètre Santé 2005; Beck, F., Guilbert, P., Eds.; Institut National de Prévention et d’Education pour la Santé (INPES): Paris, France, 2007; pp. 355–367. [Google Scholar]

- Velter, A. Rapport Enquête Presse Gay 2004; Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le Sida et les hépatites (ANRS), INstitut de Veille Sanitaire (INVS): Saint-Maurice, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Paget, L.M.; Chee, C.C.; Sauvage, C.; Saboni, L.; Beltzer, N.; Velter, A. Factors associated with suicide attempts by sexual minorities: Results from the 2011 gay and lesbian survey. Rev. Epidemiol. Sante Publique 2016, 64, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, M.; Semlyen, J.; Tai, S.S.; Killaspy, H.; Osborn, D.; Popelyuk, D.; Nazareth, I. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry 2008, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R.J.; Derlega, V.J.; Griffin, J.L.; Krowinski, A.C. Stressors for Gay Men and Lesbians: Life Stress, Gay-Related Stress, Stigma Consciousness, and Depressive Symptoms. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 22, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.; Johnson, R.M.; Corliss, H.L.; Molnar, B.E.; Azrael, D. Emotional distress among LGBT touth: The influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. J. Youth Adolesc. 2009, 38, 1001–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I.; Dietrich, J.; Schwartz, S. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders and suicide attempts in diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1004–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I.H.; Northridge, M.E. The Health of Sexual Minorities: Public Health Perspectives of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Populations; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, I.H. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiPlacido, J. Minority stress among lesbians, gay men and bisexuals: A consequence of heterosexism, homophobia and stigmatization. In Stigma and Sexual Orientation; Herek, G.M., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 138–159. [Google Scholar]

- Cass, V.C. Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. J. Homosex. 1979, 4, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosario, M.; Hunter, J.; Maguen, S.; Gwadz, M.; Smith, R. The Coming-Out Process and Its Adaptational and Health-Related Associations among Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Youths: Stipulation and Exploration of a Model. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2001, 29, 133–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Augelli, A.; Grossman, A.; Salter, N.; Vasey, J.; Starks, M.; Sinclair, K. Predicting the suicide attempts of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2005, 35, 646–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Augelli, A.; Grossman, A.; Starks, M. Childhood gender atypicality, victimization, and PTSD among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. J. Interpers. Violence 2006, 21, 1462–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragowski, E.A.; Halkitis, P.N.; Grossman, A.H.; D’Augelli, A.R. Sexual Orientation Victimization and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2011, 23, 226–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beals, K.P.; Peplau, L.A.; Gable, S.L. Stigma management and well-being: The role of perceived social support, emotional processing, and suppression. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critcher, C.; Ferguson, M. The cost of keeping it hidden: Decomposing concealment reveals what makes it depleting. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2014, 143, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, K.H.; Hebl, M.R. The disclosure dilemma for gay men and lesbians: “Coming out” at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaSala, M. Gay male couples: The importance of coming out and being out to parents. J. Homosex. 2000, 39, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, D.M.; Lehavot, K.; Meyer, I.H. Minority stress and physical health among sexual minority individuals. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilkington, N.W.; D’Augelli, A.R. Victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in community settings. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzo, G.; Pace, U.; Lo Cascio, V.; Craparo, G.; Schimmenti, A. Bullying Victimization, Post-Traumatic Symptoms, and the Mediating Role of Alexithymia. Child Indic. Res. 2014, 7, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonet, L.; Wells, B.E.; Parsons, J.T. A positive look at a difficult time: A strength based examination of coming out for lesbian and bisexual women. J. LGBT Health Res. 2007, 3, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Augelli, A.R. Mental Health Problems among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youths Ages 14 to 21. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2002, 7, 433–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Huebner, D.; Diaz, R.M.; Sanchez, J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnell, E.A.; Birkett, M.; Mustanski, B. Families Matter: Social Support and Mental Health Trajectories among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, J.C.; Lazarus, R.S. Cognitive style, stress perception and coping. In Hand Book of Stress and Anxiety: Knowledge, Theory and Treatment; Kutasha, I.L., Ed.; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1980; pp. 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Psychological Stress and Coping Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping; Springer Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R. An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1980, 21, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, R.F. Suicide as escape from self. Psychol. Rev. 1990, 97, 90–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lester, D. The role of shame in suicide. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1997, 27, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mokros, H.B. Suicide and Shame. Am. Behav. Sci. 1995, 38, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everall, R.D. Being in the Safety Zone: Emotional Experiences of Suicidal Adolescents and Emerging Adults. J. Adolesc. Res. 2006, 21, 370–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T. 1921-Cognitive Therapy of Depression; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; ISBN 0898620007. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 9780898621839. [Google Scholar]

- Nock, M.K.; Wedig, M.M.; Holmberg, E.B.; Hooley, J.M. The emotion reactivity scale: Development, evaluation, and relation to self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Behav. Ther. 2008, 39, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Dovidio, J.F.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Phills, C.E. An implicit measure of anti-gay attitudes: Prospective associations with emotion regulation strategies and psychological distress. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 1316–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graziani, P.; Rusinek, S.; Servant, D.; Hautekeete-Sence, D.; Hautekeete, M. Validation française du questionnaire de coping “way of coping check-list-revised” (W.C.C.-R.) et analyse des événements stressants du quotidien. J. Ther. Comport. Cognit. 1998, 8, 100–112. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Graziani, P. Spécificité de L’évaluation, du Vécu Émotionnel et du Coping des Sujets Souffrant de Troubles Anxieux Confrontés à des Évènements Stressants. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Charles de Gaulle-Lille 3, Villeneuve-d’Ascq, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Larson, J.E.; Hautamaki, J.; Matthews, A.; Kuwabara, S.; Rafacz, J.; Walton, J.; Wassel, A.; O’Shaughnessy, J. What Lessons do Coming Out as Gay Men or Lesbians have for People Stigmatized by Mental Illness? Community Ment. Health J. 2009, 45, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savin-Williams, R.C.; Ream, G.L. Sex variations in the disclosure to parents of same-sex attractions. J. Fam. Psychol. 2003, 17, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, A.N.; Szymanski, D.M. Family Dynamics and Changes in Sibling of Origin Relationship after Lesbian and Gay Sexual Orientation Disclosure. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2011, 33, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, R. Family and friendship relationships after young women come out as bisexual or lesbian. J. Homosex. 2000, 38, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legate, N.; Ryan, R.M.; Weinstein, N. Is Coming Out Always a “Good Thing”? Exploring the Relations of Autonomy Support, Outness, and Wellness for Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Individuals. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2012, 3, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grov, C.; Bimbi, D.S.; Nanin, J.E.; Parsons, J.T. Race, ethnicity, gender, and generational factors associated with the coming-out process among lesbian, and bisexual individuals. J. Sex Res. 2006, 43, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Augelli, A.R.; Grossman, A.H.; Starks, M.T.; Sinclair, K.O. Factors Associated with Parents’ Knowledge of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Youths’ Sexual Orientation. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2010, 6, 178–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, R. Stigma management and gay identity development. Soc. Work 1991, 36, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pachankis, J.E.; Goldfried, M.R.; Ramrattan, M.E. Extension of the rejection sensitivity construct to the interpersonal functioning of gay men. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charbonnier, É.; Graziani, P. Stress, risque suicidaire et annonce de son homosexualité. Serv. Soc. 2013, 59, 1–6. (In French) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, J. Putting stress into words: Health, linguistic, and therapeutic implications. Behav. Res. Ther. 1993, 31, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, J. Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychol. Sci. 1997, 8, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragins, B.R. Sexual orientation in the workplace: The unique work and career experiences of gay, lesbian and bisexual workers. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, M. Coming Out Growth: Conceptualizing and Assessing Experiences of Stress-Related Growth Associated with Coming Out as Lesbian or Gay. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Akron, Akron, OH, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, M.D.; Waehler, C.A. Coming Out Growth: Conceptualizing and measuring stress-related growth associated with coming out to others as a sexual minority. J. Adult Dev. 2010, 17, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coursaud, J.B. L’Homosexualité Entre Préjugés et Réalités; Milan: Toulouse, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Angst, J.; Gamma, A.; Gastpar, M.; Lepine, J.P.; Mendlewicz, J.T.A. Gender differences in depression. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2002, 252, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanagh, J.; Carson, A.; Sharpe, M. Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: A systematic review. Psychol. Med. 2003, 33, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Lesage, A.; Seguin, M.; Chawky, N.; Vanier, C.; Lipp, O.; Turecki, G. Patterns of co-morbidity in male suicide completers. Psychol. Med. 2003, 33, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wieczorek, W.; Conwell, Y.; Tu, X. Psychological strains and youth suicide in rural China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 2003–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speckens, A.; Hawton, K. Social problem solving in adolescents with suicidal behavior: A systematic review. Suicide Life-Threat. 2005, 35, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, K.; Stelzer, J.; Bergman, J. Problem solving, stress, and coping in adolescent suicide attempts. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 1995, 25, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blankstein, K.; Lumley, C.; Crawford, A. Perfectionism, hopelessness, and suicide ideation: Revisions to diathesis-stress and specific vulnerability models. J. Ration. Emot. Cognit. Behav. Ther. 2007, 25, 279–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, R.C. Bisexual Identities. In Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identities over the LifespanPsychological Perspectives; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995; pp. 48–86. [Google Scholar]

- Fenner, Y.; Garland, S.M.; Moore, E.E.; Jayasinghe, Y.; Fletcher, A.; Tabrizi, S.N.; Gunasekaran, B.; Wark, J. Web-Based recruiting for Health Research Using a Social Networking Site: An Exploratory Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouchieu, C.; Castetbon, K.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Touvier, M. Prise de compléments alimentaires évaluée par autoquestionnaire sur Internet, étude NutriNet-Santé. Rev. Epidemiol. Sante Publique 2012, 60, S95. (In French) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRose, R.; Lin, C.A.; Eastin, M.S. Unregulated Internet Usage: Addiction, Habit, or Deficient Self-Regulation? Media Psychol. 2003, 5, 225–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastro, D.E.; Eastin, M.S.; Tamborini, R. Internet Search Behaviors and Mood Alterations: A Selective Exposure Approach. Media Psychol. 2002, 4, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, S.; Morgan, S.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Boylan, C.; Crowley, S.; Gahan, H.; Howley, J.; Staunton, D.; Guerin, S. Deliberate self-harm in children and adolescents: A qualitative study exploring the needs of parents and carers. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 13, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, S.; McFarlane, M.; Rietmeijer, C. HIV and sexually transmitted infection risk behaviors among men seeking sex with men on-line. Am. J. Public Health 2001, 91, 988–989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bull, S.; Lloyd, L.; Rietmeijer, C.; McFarlane, M. Recruitment and retention of an online sample for an HIV prevention intervention targeting men who have sex with men: The smart sex quest project. AIDS Care 2004, 16, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charbonnier, E.; Graziani, P. La perception de jeunes lesbiennes et gais concernant l’attitude de leurs parents à l’égard de leur homosexualité. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2011, 30, 31–46. (In French) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean (±SD) |

|---|---|

| Primary appraisal | |

| Risk “Lose respect and affection” | 2.35 (±1.11) |

| Risk “Cause suffering” | 1.92 (±1.21) |

| Risk “Harm myself or others” | 1.54 (±0.96) |

| Risk “Appear as a careless, unethical person” | 0.94 (±1.12) |

| Risk “Incompetence and failure” | 0.5 (±0.74) |

| Secondary appraisal | |

| “Accept the situation” | 2.98 (±1.25) |

| “Seek information before acting” | 1.25 (±1.33) |

| “Stick to the plan and keep doing what you wanted to do” | 1.23 (±1.45) |

| “Change the situation or act upon it” | 0.89 (± 1.21) |

| Emotional Factors at the beginning of the disclosure | |

| Anxious anticipation | 2.42 (±0.88) |

| Mastery | 1.23 (±1.06) |

| Hostility and disappointment | 1.21 (±1.08) |

| Well-being | 1.08 (±0.96) |

| Jealousy | 0.18 (±0.50) |

| Emotional Factors at the end of the disclosure | |

| Well-being and mastery | 1.90 (±1.10) |

| Anxious anticipation | 1.14 (±1.07) |

| Hostility and disappointment | 1.06 (±1.16) |

| Jealousy | 0.22 (±0.56) |

| Coping strategies mobilised during disclosure | |

| Positive development | 1.51 (±0.66) |

| Help seeking | 1.46 (±0.73) |

| Minimization | 1.25 (±0.59) |

| Problem solving | 1.21 (±0.48) |

| Acceptance | 1.14 (±0.53) |

| Avoidance | 1.10 (±0.57) |

| Preparation and escape | 0.98 (±0.61) |

| Aggression | 0.59 (±0.66) |

| Model | Standardized B | SE | t | df | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 195 | 0.36 | |||

| Avoidance coping | 0.58 *** | 0.11 | 10.18 | ||

| Development coping | −0.16 ** | 0.10 | −2.75 | ||

| Model 2 | 194 | 0.38 | |||

| Avoidance coping | 0.50 *** | 0.12 | 8.21 | ||

| Development coping | −0.17 ** | 0.10 | −3.09 | ||

| Risk 3 Incompetence and Failure | 0.15 * | 0.10 | 2.44 | ||

| Risk 4 To cause suffering | 0.13 * | 0.05 | 2.16 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Charbonnier, E.; Dumas, F.; Chesterman, A.; Graziani, P. Characteristics of Stress and Suicidal Ideation in the Disclosure of Sexual Orientation among Young French LGB Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020290

Charbonnier E, Dumas F, Chesterman A, Graziani P. Characteristics of Stress and Suicidal Ideation in the Disclosure of Sexual Orientation among Young French LGB Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(2):290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020290

Chicago/Turabian StyleCharbonnier, Elodie, Florence Dumas, Adam Chesterman, and Pierluigi Graziani. 2018. "Characteristics of Stress and Suicidal Ideation in the Disclosure of Sexual Orientation among Young French LGB Adults" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 2: 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020290

APA StyleCharbonnier, E., Dumas, F., Chesterman, A., & Graziani, P. (2018). Characteristics of Stress and Suicidal Ideation in the Disclosure of Sexual Orientation among Young French LGB Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(2), 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020290