Functioning and Disability Analysis of Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury by Using the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

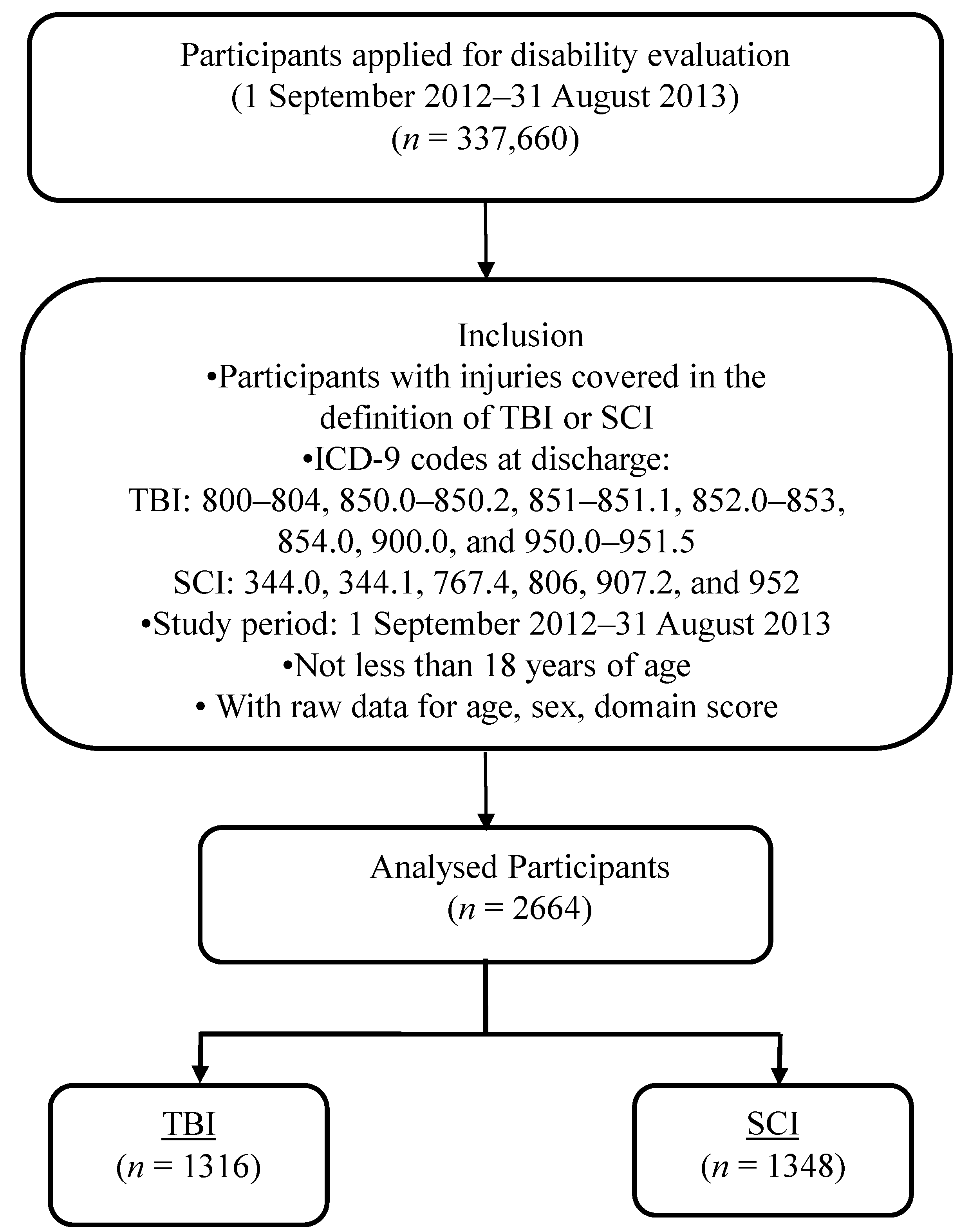

2.1. Sample

2.2. Instruments: Domain and Summary Scores of the WHODAS 2.0

2.3. Procedure

| Variables | TBI (n = 1316) | SCI (n = 1348) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Sex | 0.293 | ||||

| Male | 873 | 66.34 | 920 | 68.25 | |

| Female | 443 | 33.66 | 428 | 31.75 | |

| Age (years) | 0.446 | ||||

| Mean, SD | 58.87 | 19.139 | 58.34 | 16.951 | |

| Median | 59.49 | 58.60 | |||

| Education | 0.073 | ||||

| No formal education | 126 | 18.39 | 95 | 14.18 | |

| Primary | 211 | 30.80 | 202 | 30.15 | |

| Above Primary | 348 | 50.80 | 373 | 55.67 | |

| Missing | 631 | 678 | |||

| Socioeconomic Status | 0.111 | ||||

| Average | 1254 | 95.29 | 1301 | 96.51 | |

| Middle low & low | 62 | 4.71 | 47 | 3.49 | |

| Place of Residence | <0.001 | ||||

| Community dwelling | 865 | 66.13 | 1000 | 74.63 | |

| Institutional dwelling | 443 | 33.87 | 340 | 25.37 | |

| Missing | 8 | 8 | |||

| Urbanization level | 0.289 | ||||

| Rural | 339 | 25.76 | 327 | 24.26 | |

| Suburban | 502 | 38.15 | 495 | 36.72 | |

| Urban | 475 | 36.09 | 526 | 39.02 | |

| Severity of impairment | <0.001 | ||||

| Mild | 259 | 19.68 | 326 | 24.18 | |

| Moderate | 351 | 26.67 | 371 | 27.52 | |

| Severe | 235 | 17.86 | 506 | 37.54 | |

| Extreme | 471 | 35.79 | 145 | 10.76 | |

3. Results

3.1. Sample Size

3.2. WHODAS 2.0 Scores and Injury Types

| Variables | TBI | SCI | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Cognition | 68.84 | 33.244 | 30.69 | 31.891 | <0.001 * |

| Mobility | 67.48 | 33.591 | 67.50 | 30.013 | 0.986 |

| Self-care | 47.55 | 39.361 | 39.77 | 35.921 | <0.001 * |

| Relationships | 72.53 | 33.586 | 45.95 | 34.794 | <0.001 * |

| Life activities | 79.27 | 34.125 | 74.04 | 36.581 | <0.001 * |

| Participation | 62.99 | 27.655 | 58.38 | 26.199 | <0.001 * |

| WHODAS 2.0 summary score | 66.38 | 26.953 | 52.00 | 23.902 | <0.001 * |

3.3. WHODAS 2.0 scores and associated factors

| Cognition | Mobility | Self-Care | Relationships | Life Activities | Participation | WHODAS 2.0 Summary Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 23.399 * | 30.934 * | 17.357 * | 30.325 * | 47.105 * | 43.926 * | 32.544 * |

| Age | 1.009 * | 1.005 * | 1.008 * | 1.007 * | 1.004 * | 1.001 * | 1.005 * |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | |||||||

| Female | 1.029 * | 1.015 * | 0.971 * | 0.97 * | 0.985 * | 1.003 | 1.001 |

| Injury | |||||||

| SCI | |||||||

| TBI | 1.988 * | 0.926 * | 1.073 * | 1.429 * | 1.029 * | 1.016 * | 1.178 * |

| Socioeconomic status | |||||||

| Average | |||||||

| Middle-low & low | 1.03 * | 1.074 * | 1.095 * | 0.996 | 1.076 * | 1.037 * | 1.047 * |

| Urbanization level | |||||||

| Urban (reference) | |||||||

| Suburban | 0.999 | 1 | 1.096 * | 0.972 * | 1.002 | 1.01 | 1.006 |

| Rural | 1.033 * | 1.028 * | 1.049 * | 1.006 | 1.015 * | 1.036 * | 1.028 * |

| Place of Residence | |||||||

| Community dwelling | |||||||

| Institutional dwelling | 1.249 * | 1.254 * | 1.427 * | 1.195 * | 1.187 * | 1.243 * | 1.247 * |

| Severity of impairment | |||||||

| Mild (reference) | |||||||

| Moderate | 1.368 * | 1.325 * | 1.5 * | 1.362 * | 1.206 * | 1.227 * | 1.3 * |

| Severe | 1.539 * | 1.601 * | 1.648 * | 1.521 * | 1.337 * | 1.297 * | 1.453 * |

| Extreme | 1.899 * | 1.723 * | 1.86 * | 1.816 * | 1.36 * | 1.414 * | 1.631 * |

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Health Statistics and Health Information Systems; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Vital Statistics in Taiwan; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Taipei, Taiwan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkers, M.P. Quality of life after traumatic brain injury: A review of research approaches and findings. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004, 4, S21–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toft, A.M.; Moller, H.; Laursen, B. The years after an injury: Long-term consequences of injury on self-rated health. J. Trauma 2010, 1, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, A.P.; Schwarzbold, M.L.; Thais, M.E.; Hohl, A.; Bertotti, M.M.; Schmoeller, R.; Nunes, J.C.; Prediger, R.; Linhares, M.N.; Guarnieri, R.; et al. Psychiatric disorders and health-related quality of life after severe traumatic brain injury: A prospective study. J. Neurotrauma 2012, 6, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.W.; Lin, C.M.; Tsai, J.T.; Hung, K.S.; Hung, C.C.; Chiu, W.T. Neurotrauma research in Taiwan. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2008, 101, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van Velzen, J.M.; van Bennekom, C.A.; Edelaar, M.J.; Sluiter, J.K.; Frings-Dresen, M.H. Prognostic factors of return to work after acquired brain injury: A systematic review. Brain Inj. 2009, 5, 385–395. [Google Scholar]

- Adriaansen, J.J.; van Asbeck, F.W.; Lindeman, E.; van der Woude, L.H.; de Groot, S.; Post, M.W. Secondary health conditions in persons with a spinal cord injury for at least 10 years: Design of a comprehensive long-term cross-sectional study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 13, 1104–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magasi, S.R.; Heinemann, A.W.; Whiteneck, G.G. Participation following traumatic spinal cord injury: An evidence-based review for research. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2008, 2, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Dryden, D.M.; Saunders, L.D.; Rowe, B.H.; May, L.A.; Yiannakoulias, N.; Svenson, L.W.; Schopflocher, D.P.; Voaklander, D.C. Utilization of health services following spinal cord injury: A 6-year follow-up study. Spinal Cord 2004, 9, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, V.K.; Kopec, J.A.; Mâsse, L.C.; Dvorak, M.F. Measuring participation among persons with spinal cord injury: Comparison of three instruments. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2010, 4, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.; Yun, S.J.; Khan, F. A comparison of participation outcome measures and the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core Sets for traumatic brain injury. J. Rehabil. Med. 2014, 2, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.C.; Tate, R.L.; Lannin, N.A.; Middleton, J.; Lane-Brown, A.; Cameron, I.D. The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale, WHODAS II: Reliability and validity in the measurement of activity and participation in a spinal cord injury population. J. Rehabil. Med. 2012, 9, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustun, T.; Kostanjsek, N.; Chatterji, S.; Rehm, J. Measuring Health and Disability: Manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ustun, T.B.; Chatterji, S.; Kostanjsek, N.; Rehm, J.; Kennedy, C.; Epping-Jordan, J.; Saxena, S.; Korffe, M.; Pull, C. Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bull. World Health Organ. 2010, 11, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, W.C.; Liou, T.H.; Huang, W.N.; Yen, C.F.; Teng, S.W.; Chang, I.C. Developing a disability determination model using a decision support system in Taiwan: A pilot study. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2013, 8, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.F.; Hwang, A.W.; Liou, T.H.; Chiu, T.Y.; Hsu, H.Y.; Chi, W.C.; Wu, T.F.; Chang, B.S.; Lu, S.J.; Liao, H.F.; et al. Validity and reliability of the Functioning Disability Evaluation Scale-Adult Version based on the WHODAS 2.0–36 items. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2014, 11, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, W.C.; Chang, K.H.; Escorpizo, R.; Yen, C.F.; Liao, H.F.; Chang, F.H.; Chiou, H.Y.; Teng, S.W.; Chiu, W.T.; Liou, T.H. Measuring disability and its predicting factors in a large database in Taiwan using the world health organization disability assessment schedule 2.0. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 12, 12148–12161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.T.; Yen, C.F.; Teng, S.W.; Liao, H.F.; Chang, K.H.; Chi, W.C.; Wang, Y.H.; Liou, T.H. Implementing disability evaluation and welfare services based on the framework of the international classification of functioning, disability and health: Experiences in Taiwan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, S.W.; Yen, C.F.; Liao, H.F.; Chang, K.H.; Chi, W.C.; Wang, Y.H.; Liou, T.H. Evolution of system for disability assessment based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: A Taiwanese study. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2013, 11, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiers, W.; Carlozzi, N.; Cernich, A.; Velozo, C.; Pape, T.; Hart, T.; Gulliver, S.; Rogers, M.; Villarreal, E.; Gordon, S.; et al. Measurement of social participation outcomes in rehabilitation of veterans with traumatic brain injury. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2012, 1, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennett, B.; Snoek, J.; Bond, M.R.; Brooks, N. Disability after severe head injury: Observations on the use of the Glasgow Outcome Scale. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1981, 4, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langlois, J.A.; Rutland-Brown, W.; Wald, M.M. The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: A brief overview. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006, 5, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Taly, A.B. Functional outcome following rehabilitation in chronic severe traumatic brain injury patients: A prospective study. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2012, 2, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zee, C.H.; Post, M.W.; Brinkhof, M.W.; Wagenaar, R.C. Comparison of the Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation with the ICF Measure of Participation and Activities Screener and the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule II in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 1, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrett, S.; Beaver, C.; Sullivan, M.J.; Herbison, G.P.; Acland, R.; Paul, C. Traumatic and non-traumatic spinal cord impairment in New Zealand: Incidence and characteristics of people admitted to spinal units. Inj. Prev. 2012, 5, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuo, C.-Y.; Liou, T.-H.; Chang, K.-H.; Chi, W.-C.; Escorpizo, R.; Yen, C.-F.; Liao, H.-F.; Chiou, H.-Y.; Chiu, W.-T.; Tsai, J.-T. Functioning and Disability Analysis of Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury by Using the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 4116-4127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120404116

Kuo C-Y, Liou T-H, Chang K-H, Chi W-C, Escorpizo R, Yen C-F, Liao H-F, Chiou H-Y, Chiu W-T, Tsai J-T. Functioning and Disability Analysis of Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury by Using the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015; 12(4):4116-4127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120404116

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuo, Chia-Ying, Tsan-Hon Liou, Kwang-Hwa Chang, Wen-Chou Chi, Reuben Escorpizo, Chia-Feng Yen, Hua-Fang Liao, Hung-Yi Chiou, Wen-Ta Chiu, and Jo-Ting Tsai. 2015. "Functioning and Disability Analysis of Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury by Using the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12, no. 4: 4116-4127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120404116

APA StyleKuo, C.-Y., Liou, T.-H., Chang, K.-H., Chi, W.-C., Escorpizo, R., Yen, C.-F., Liao, H.-F., Chiou, H.-Y., Chiu, W.-T., & Tsai, J.-T. (2015). Functioning and Disability Analysis of Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury by Using the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(4), 4116-4127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120404116