Effects of Compulsory Schooling on Mortality: Evidence from Sweden

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Authors | Country/Data Source | Year/Content of the Reform | Identification Strategy | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albouy and Lequien [18] | France/ Longitudinal data: Echantillon Demographique Permanent Census data (1968, 1975, 1982, 1990, 1999) Register Data of Deaths from 1968–2005 | 1936 (Zay Reform)/6→7 1967 (Berthoin Reform)/7→9 | Regression Discontinuity Design on birth cohorts | Zay Reform: survival till 82 for those surviving until 1968 increased by 6% (Wald-estimate). Berthoin Reform: survival until 52 for those surviving until 1968 increased by 1% (Wald-estimate) Effects statistically insignificant |

| Gathmann et al. [17] | Various European Countries/ Human Mortality Database European Social Service International Social Survey Programme Survey of Health Ageing and Retirement | 19 different Reforms | Regression Discontinuity Design on birth cohorts Meta analysis (for pooled estimate over the 19 reforms) | Substantial heterogeneity in time and space: Effects probably larger for reforms implemented earlier in the 20th century. Gender differences: no effects for women; reduction of 2.8% in 20-year male mortality from age 18 (reduced form) |

| Van Kippersluis et al. [19] | Netherlands/ Dutch Cross-sectional General Household Survey (1997–2005) Tax Records (1998) Cause-of-Death register (1998–2005) Dutch Municipality Register | 1928/6→7 | Regression Discontinuity Design on date of birth (individual data) | 2%–3% decrease in mortality until the age of 89 for those surviving until the age of 81 (reduced form). Reduced form similar to two-stage least squares estimates as a rise in education between 0.6–1, depending on specification |

| Clark and Royer [10] | England and Wales/ Mortality Data from the Office for National Statistics: All deaths for the years 1970 to 2007 | 1947/8→9 1972/9→10 | Regression Discontinuity Design | Hardly any evidence for a reduction of mortality; some estimates even with a positive sign |

| Meghir et al. [14] | Sweden Swedish population censuses; all individuals born in Sweden between 1946 and 1957 | Implemented by municipalities between 1949 and 1962. From 1962 nationwide/ (7 or 8)→9 | Reduced Form Difference in Difference/IV | Short-lived gain in expected male years of life from a shift in mortality from ages 45–50 to ages 50–55. Overall life expectancy not significantly affected Heterogeneity with respect to social background |

| Lleras-Muney [13] | U.S./ Census (1960, 1970, 1980) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey | 1915–1939 Various U.S. states with different extensions | Difference in Difference/IV Regression Discontinuity Design | Extension of one year of education decreases 10 year mortality for those surviving until 1960 by 3.6% (instrumental variable (IV)) relative to a baseline mortality of 10%. Estimates challenged by Mazumder [16]: Sensitive to state-specific time trends; effects mainly due to earliest cohorts |

| Lager and Torssander [15] | Sweden/ Swedish population censuses All individuals born in Sweden between 1943 and 1955 | Implemented by municipalities between 1949 and 1962 From 1962, nationwide/ (7 or 8)→9 | Reduced Form Difference in Difference/IV | Overall, all-cause mortality not significantly affected Lower mortality from causes related to education (e.g., cancer and accidents). Socioeconomic heterogeneity with lower mortality among the least educated |

2. Institutional Background and Methodological Section

2.1. Background on the Educational System and the Reform

2.2. Data and Sample Selection

2.3. Variable Definitions

| Mean | Standard Error | min | max | N | |

| 10 Year Death Rate | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.027 | 731,791 |

| 20 Year Death Rate | 0.017 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.047 | 731,791 |

| 30 Year Death Rate | 0.026 | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.073 | 731,791 |

| 40 Year Death Rate | 0.048 | 0.016 | 0.010 | 0.111 | 731,791 |

| 50 Year Death Rate | 0.097 | 0.035 | 0.025 | 0.218 | 731,791 |

| 60 Year Death Rate | 0.193 | 0.069 | 0.050 | 0.427 | 731,791 |

| 70 Year Death Rate | 0.373 | 0.118 | 0.105 | 0.746 | 731,791 |

| Male | 0.509 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 731,791 |

| Treatment | 0.406 | 0.272 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 731,791 |

| Urban | 0.269 | 0.223 | 0.040 | 1.000 | 731,791 |

| Age at Census 1935 | 7.622 | 2.299 | 4.000 | 11.000 | 731,791 |

| G | 400 |

2.3.1. Computing Mortality Rates

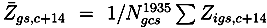

denotes the size of cohort c of sex s in county g at the end of 1935 and

denotes the size of cohort c of sex s in county g at the end of 1935 and  , the number of deaths of the corresponding cell during year t. The incomplete deaths between 1935 and 1946 have been imputed under a missing at random assumption. The imputed death rates roughly match death rates from official statistics. Computing death rates from a later census to circumvent the missing values in the Death Index was not possible, due to migration into cities. The cell-specific population in 1950 deviates from the population 20 years earlier. This would be problematic with respect to the treatment assignment. As students in cities are more likely to have experienced extended schooling, many more individuals would be assigned as treated if a later census would have been used.

, the number of deaths of the corresponding cell during year t. The incomplete deaths between 1935 and 1946 have been imputed under a missing at random assumption. The imputed death rates roughly match death rates from official statistics. Computing death rates from a later census to circumvent the missing values in the Death Index was not possible, due to migration into cities. The cell-specific population in 1950 deviates from the population 20 years earlier. This would be problematic with respect to the treatment assignment. As students in cities are more likely to have experienced extended schooling, many more individuals would be assigned as treated if a later census would have been used.2.3.2. Treatment Indicator

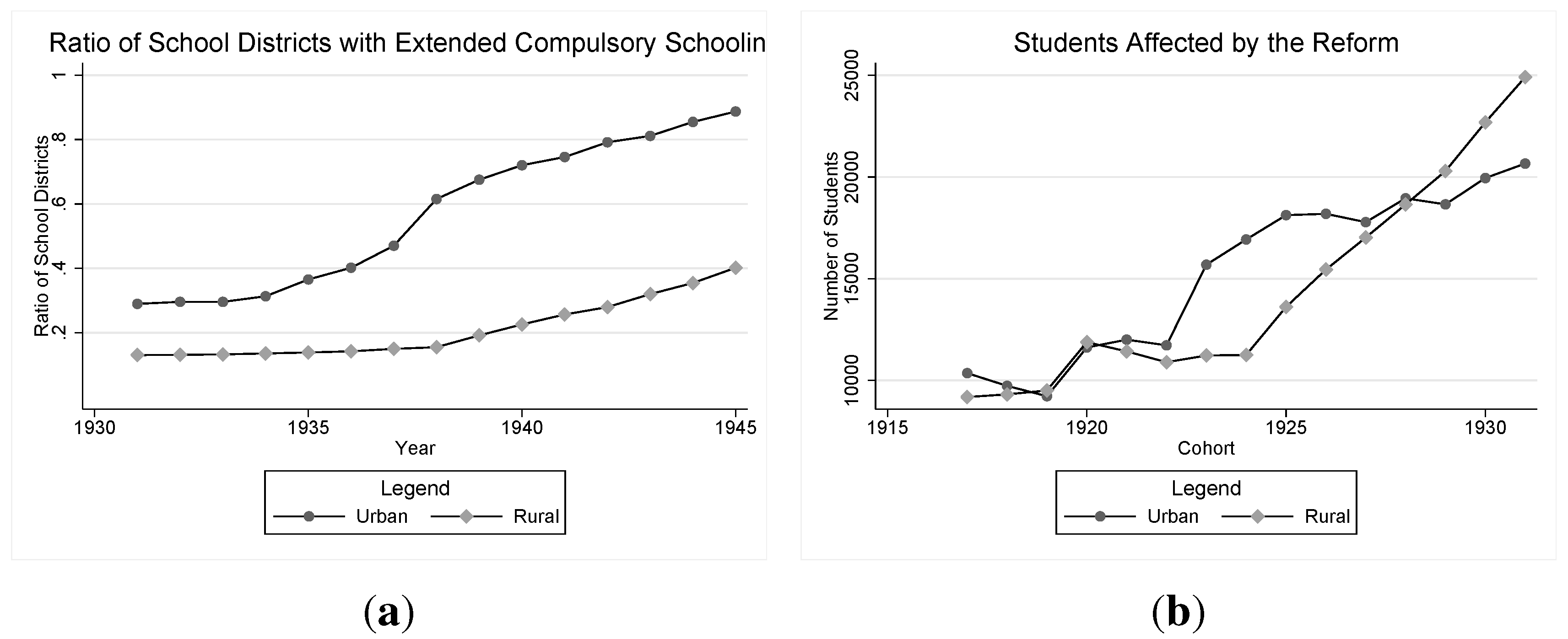

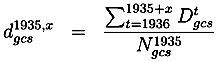

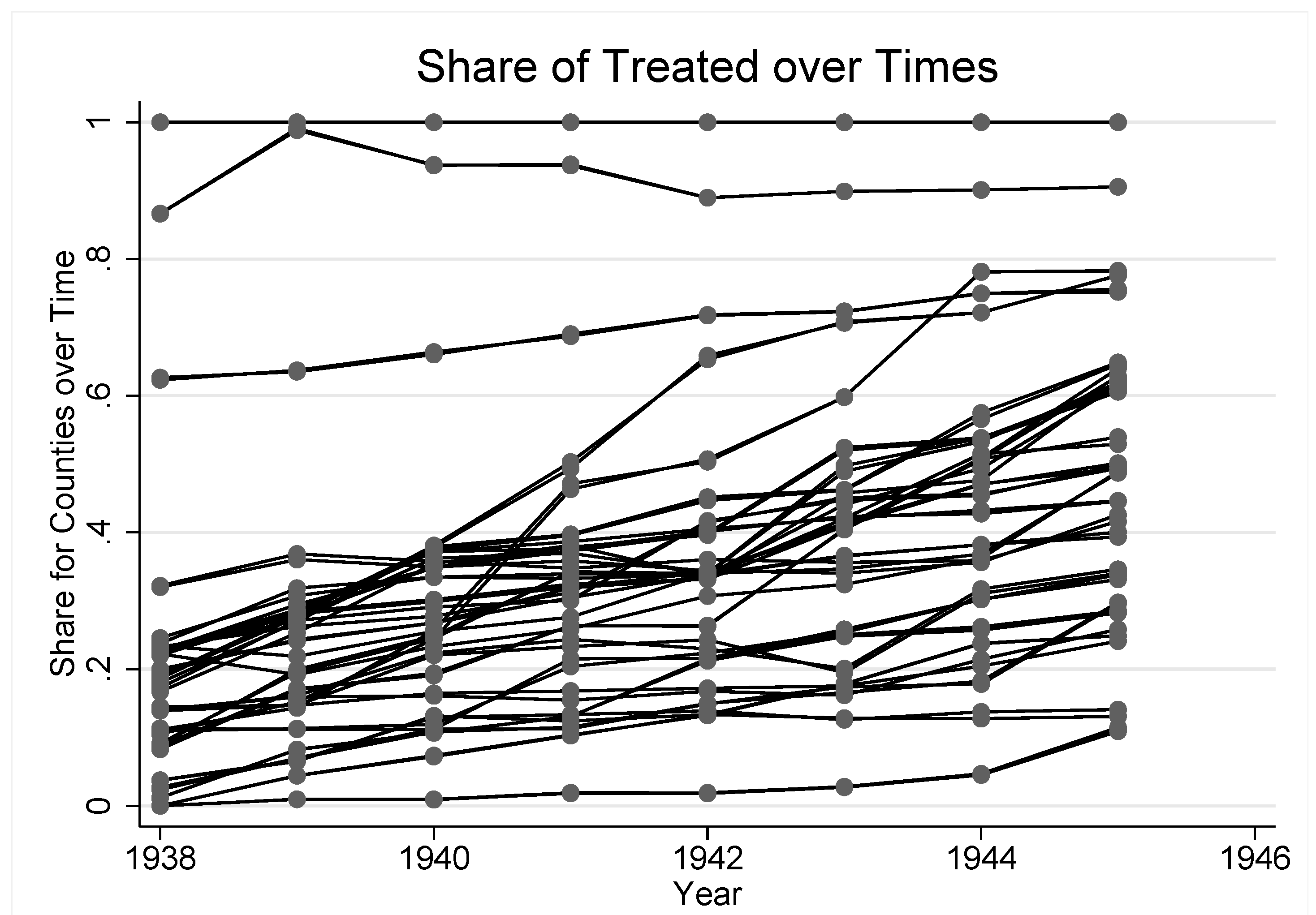

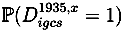

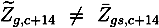

. As we combine rural and urban areas for reasons mentioned in Section 2.2, the final treatment share is constructed as a weighted average between the two areas in every region, g. The weights are given by the specific cohort sizes from the census. In Figure 2, we have plotted

. As we combine rural and urban areas for reasons mentioned in Section 2.2, the final treatment share is constructed as a weighted average between the two areas in every region, g. The weights are given by the specific cohort sizes from the census. In Figure 2, we have plotted  for each region.

for each region.

2.4. Empirical Strategy

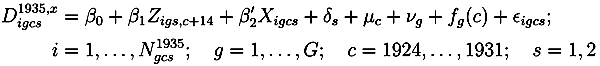

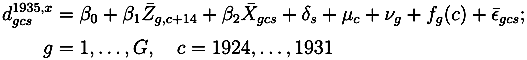

is assumed to be given by a linear probability model:

is assumed to be given by a linear probability model:

gives the number of observations within a specific gender-cohort-region cell. In the basic regressions without the inclusion of cohort trends, β1 is identified by deviations from a statewide cohort trend and regional specific intercepts and, therefore, constitutes a simple difference-in-difference estimate. This specification has been shown to be sensitive concerning the inclusion of regional specific trends (see Mazumder [16]).

gives the number of observations within a specific gender-cohort-region cell. In the basic regressions without the inclusion of cohort trends, β1 is identified by deviations from a statewide cohort trend and regional specific intercepts and, therefore, constitutes a simple difference-in-difference estimate. This specification has been shown to be sensitive concerning the inclusion of regional specific trends (see Mazumder [16]).

. In general, the constructed treatment share,

. In general, the constructed treatment share,  , as

, as  , does not distinguish between gender and weighs all school districts equally by construction. This creates a (possibly non-classical) measurement error in the instrument. In the following, we will carefully state the assumptions that are necessary for inference on the effects of the treatment, β1.

, does not distinguish between gender and weighs all school districts equally by construction. This creates a (possibly non-classical) measurement error in the instrument. In the following, we will carefully state the assumptions that are necessary for inference on the effects of the treatment, β1.3. Results and Discussion

| Death Rate: | 10 Years | 20 Years | 30 Years | 40 Years | 50 Years | 60 Years | 70 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No trends: | |||||||

| Treatment | −0.004* | −0.006* | −0.008* | −0.011** | −0.010* | −0.013 | −0.028* |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.008) | (0.013) | |

| Urban | −0.004 | −0.015 | −0.026 | 0.001 | −0.009 | −0.086 | −0.034 |

| (0.012) | (0.018) | (0.021) | (0.028) | (0.051) | (0.083) | (0.111) | |

| Male | 0.002** | 0.006** | 0.012** | 0.022** | 0.051** | 0.102** | 0.164** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| R2 | 0.659 | 0.734 | 0.827 | 0.894 | 0.933 | 0.951 | 0.973 |

| Linear county trends: | |||||||

| Treatment | −0.005 | −0.014** | −0.025** | −0.023** | −0.029** | −0.016 | −0.026 |

| (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.010) | (0.012) | (0.019) | |

| Urban | −0.003 | −0.010 | −0.015 | 0.008 | −0.001 | −0.092 | −0.012 |

| (0.012) | (0.019) | (0.022) | (0.030) | (0.054) | (0.086) | (0.115) | |

| Male | 0.002** | 0.006** | 0.012** | 0.022** | 0.051** | 0.102** | 0.164** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| R2 | 0.682 | 0.760 | 0.848 | 0.901 | 0.936 | 0.954 | 0.975 |

| Linear/Quadratic county trends: | |||||||

| Treatment | −0.008* | −0.020** | −0.028** | −0.023* | −0.034** | −0.024 | −0.019 |

| (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.011) | (0.013) | (0.021) | |

| Urban | −0.005 | −0.006 | −0.014 | −0.002 | 0.001 | −0.099 | −0.039 |

| (0.014) | (0.020) | (0.025) | (0.033) | (0.060) | (0.095) | (0.124) | |

| Male | 0.002** | 0.006** | 0.012** | 0.022** | 0.051** | 0.102** | 0.164** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| R2 | 0.705 | 0.773 | 0.856 | 0.907 | 0.939 | 0.957 | 0.977 |

| G | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 |

| Baseline Mortality | 0.007 | 0.017 | 0.026 | 0.048 | 0.097 | 0.193 | 0.373 |

| Specification: | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death Rate: | |||||||||||

| 10 Years | |||||||||||

| Treatment | −0.001 | −0.004* | −0.004* | −0.004* | −0.004* | −0.006 | −0.005 | −0.005 | −0.005 | −0.007* | −0.007* |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| 20 Years | |||||||||||

| Treatment | −0.003* | −0.006** | −0.006* | −0.006** | −0.006* | −0.016** | −0.014** | −0.015** | −0.014** | −0.016** | −0.016** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.004) | |

| 30 Years | |||||||||||

| Treatment | −0.004** | −0.008** | −0.008* | −0.009** | −0.008* | −0.029** | −0.026** | −0.027** | −0.025** | −0.028** | −0.028** |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.005) | |

| 40 Years | |||||||||||

| Treatment | −0.006 | −0.012** | −0.011** | −0.012** | −0.011** | −0.030** | −0.023** | −0.027** | −0.023** | −0.026** | −0.026** |

| (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| 50 Years | |||||||||||

| Treatment | −0.009 | −0.013* | −0.010* | −0.014* | −0.010* | −0.045** | −0.029** | −0.037** | −0.029** | −0.029** | −0.030** |

| (0.008) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.011) | (0.010) | (0.011) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.010) | |

| 60 Years | |||||||||||

| Treatment | −0.018 | −0.017* | −0.012 | −0.020* | −0.013 | −0.052* | −0.018 | −0.033 | −0.016 | −0.022 | −0.022 |

| (0.016) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.010) | (0.008) | (0.020) | (0.012) | (0.018) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | |

| 70 Years | |||||||||||

| Treatment | −0.036 | −0.035* | −0.028* | −0.040* | −0.028* | −0.080* | −0.026 | −0.054 | −0.026 | −0.031 | −0.029 |

| (0.028) | (0.014) | (0.013) | (0.016) | (0.013) | (0.034) | (0.020) | (0.032) | (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.018) | |

| Urban | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Male | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| County FE | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Cohort FE | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| County trends (linear) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Gender trend | √ | ||||||||||

| Restricted sample | √ | ||||||||||

| G | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 368 |

| Death Rate: | 10 Years | 20 Years | 30 Years | 40 Years | 50 Years | 60 Years | 70 Years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specification: | ||||||||

| Interacted | ||||||||

| No trends: | ||||||||

| Treatment | −0.004* (0.002) | −0.005* (0.002) | −0.007* (0.003) | −0.011** (0.004) | −0.010 (0.006) | −0.012 (0.011) | −0.031* (0.015) | |

| Interaction | −0.000 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.002 (0.002) | 0.000 (0.002) | −0.001 (0.005) | −0.003 (0.009) | 0.007 (0.010) | |

| Linear county trends: | ||||||||

| Treatment | −0.005 (0.003) | −0.013** (0.005) | −0.024** (0.006) | −0.023** (0.007) | −0.028** (0.010) | −0.014 (0.013) | −0.029 (0.020) | |

| Interaction | −0.000 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.002 (0.002) | −0.000 (0.002) | −0.001 (0.005) | −0.003 (0.009) | 0.006 (0.010) | |

| Men Only | ||||||||

| No trends: | ||||||||

| Treatment | −0.003 (0.002) | −0.008* (0.003) | −0.011* (0.004) | −0.013* (0.005) | −0.013 (0.007) | −0.010 (0.011) | −0.030 (0.019) | |

| Linear county trends: | ||||||||

| Treatment | −0.010 (0.005) | −0.024** (0.007) | −0.029** (0.010) | −0.020 (0.013) | −0.026 (0.015) | −0.012 (0.021) | −0.040 (0.028) | |

| Women Only | ||||||||

| No trends: | ||||||||

| Treatment | −0.004 (0.002) | −0.003 (0.003) | −0.005 (0.004) | −0.009 (0.005) | −0.008 (0.006) | −0.016 (0.010) | −0.025 (0.013) | |

| Linear county trends: | ||||||||

| Treatment | 0.002 (0.006) | −0.004 (0.007) | −0.021** (0.008) | −0.028** (0.011) | −0.032* (0.014) | −0.019 (0.018) | −0.011 (0.025) |

| Death Rate: | 10 Years | 20 Years | 30 Years | 40 Years | 50 Years | 60 Years | 70 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No trends: | |||||||

| Treatment | −0.584* | −0.354** | −0.334** | −0.278** | −0.167* | −0.115* | −0.142* |

| (0.243) | (0.128) | (0.119) | (0.078) | (0.064) | (0.055) | (0.058) | |

| Marginal effects | −0.004 | −0.005 | −0.008 | −0.012 | −0.014 | −0.017 | −0.031 |

| Linear county trends: | |||||||

| Treatment | −0.473 | −0.764* | −1.037** | −0.565** | −0.350** | −0.105 | −0.121 |

| (0.586) | (0.300) | (0.239) | (0.177) | (0.121) | (0.079) | (0.085) | |

| Marginal effects | −0.003 | −0.012 | −0.026 | −0.025 | −0.030 | −0.016 | −0.027 |

| G | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 |

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Health, United States, 2011; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Education at a Glance 2012 OECD Indicators: OECD Indicators. Education at a Glance; OECD Publishing: Lanham, MD, USA, 2012.

- Statistics Sweden, Livslängden i Sverige 2001–2010: Livslängdstabeller För Riket Och Länen. Demografiska Rapporter, SCB: Orebro, Sweden, 2011.

- Oreopoulos, P.; Salvanes, K.G. Priceless: The nonpecuniary benefits of schooling. J. Econ. Perspect. 2011, 25, 159–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.M.; Lleras-Muney, A. Education and Health: Evaluating Theories and Evidence; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, M. On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. J. Polit. Econ. 1972, 80, 223–255. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, J.N. In sickness and in healthtill education do us part: Education effects on hospitalization. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2008, 27, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemptner, D.; Jürges, H.; Reinhold, S. Changes in compulsory schooling and the causal effect of education on health: Evidence from Germany. J. Health Econ. 2011, 30, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürges, H.; Reinhold, S.; Salm, M. Does schooling affect health behavior? Evidence from the educational expansion in Western Germany. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2011, 30, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.; Royer, H. The effect of education on adult mortality and health: Evidence from Britain. Am. Econ. Rev. In press.

- Oreopoulos, P. Estimating average and local average treatment effects of education when compulsory schooling laws really matter. Am. Econ. Rev. 2006, 96, 152–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silles, M.A. The causal effect of education on health: Evidence from the United Kingdom. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2009, 28, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleras-Muney, A. The relationship between education and adult mortality in the United States. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2005, 72, 189–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghir, C.; Palme, M.; Simeonova, E. Education, Health and Mortality: Evidence from a Social Experiment, IZA Discussion Paper; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lager, A.C.J.; Torssander, J. Causal effect of education on mortality in a quasi-experiment on 1.2 million Swedes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8461–8466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, B. The effects of education on health and mortality. Nordic Econ. Policy 2012, 1, 261–303. [Google Scholar]

- Gathmann, C.; Jürges, H.; Reinhold, S. Compulsory Schooling Reforms, Education and Mortality in Twentieth Century Europe; CESifo: Munich, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Albouy, V.; Lequien, L. Does compulsory education lower mortality? J. Health Econ. 2009, 28, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kippersluis, H.; O’Donnell, O.; van Doorslaer, E. Long-run returns to education does schooling lead to an extended old age? J. Hum. Resour. 2011, 46, 695–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecklesiastikdepartementet, Betänkande Och Förslag Angående Obligatorisk Sjuårig Folkskola, SOU 1935:58; Ivar Hagströms Boktryckeri A.B.: Stockholm, Sweden, 1935.

- Fredriksson, V.A. Svenska Folkskolans Historia; Albert Bonniers Förlag: Stockholm, Sweden, 1950; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M. Utbildningsexpansion, Jämlikhet Och Avlänkning: Studier I Utbildningspolitik Och Utbildningsplanering 1933–1985. In Goteborg Studies in Educational Sciences; Barnes & Noble: Boston, MA, USA, 1988; Volume 66. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson, V.A. Svenska Folkskolans Historia; Albert Bonniers Förlag: Stockholm, Sweden, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson, J.O. Can Education be Equalized: The Swedish Case in Comparative Perspective; Westview Press: Lexington, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lindmark, E. Läroplaner Och Andra Styrdokument Före 1970; Stockholm University: Stockholm, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöberg, M. Skydd, hinder eller möjlighet? Barn 2009, 34, 123138. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, E.; Westberg, J. Utbildningshistoria: En Introduktion; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Meghir, C.; Palme, M. Educational reform, ability, and family background. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ståhlberg, A.C. Socialförsäkringarna i Sverige: Andra upplagan; SNS Frlag: Stockholm, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- SOU. Betänkande Angående Moderskapsskydd, Statens Offentliga Utredningar 1929:27; Statens Offentliga Utredningar: Stockholm, Sweden, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Ström, J. Den socialmedicinska övervakningen av blivande mödrar och spädbarn i Sverige. En statistisk analys av verksamhetens omfattning, arbetssätt och ekonomi. Soc. Med. Tidskr. 1942, 19, 22–43. [Google Scholar]

- Heidenheimer, A.J.; Elvander, N.; Hultén, C. The Shaping of the Swedish Health System; Taylor & Francis: New Delhi, India, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Sweden, Statistisk årsbok För Sverige; Statistiska Centralbyrån: Stockholm, Sweden, 1938–1946.

- Wisselgren, M.J. Att föda barn–från privat till offentlig angelägenhet: Förlossningsvårdens institutionalisering i Sundsvall 1900–1930. Ph.D. Thesis, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wolke, L.E. Svenska Frivilliga: Militära Uppdrag I Utlandet Under 1800-Och 1900-Talen; Historiska Media: Stockholm, Sweden, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Skolöverstyrelsen, Tabeller; Skolöverstyrelsens arkiv, Statistiska kontoret: Stockholm, Sweden, 1945.

- Statistics Sweden. Särskilda Folkräkningen 1935/36. 1937.

- Swedish Death Index 1901–2009; Federation of Swedish Genealogical Societies: Farsta, Sweden, 2010.

- Holmlund, H. A Researcher’s Guide to the Swedish Compulsory School Reform; Centre for the Economics of Education, London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, W. Ecological correlations and the behavior of individuals. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1950, 15, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, D.A. Ecological inference and the ecological fallacy. Int. Encycl. Soc. Behav. Sci. 1999, 6, 4027–4030. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Sweden, Dödsorsaker år 1940; Stockholm: Kungl. Statistiska Centralbyrån: Stockholm, Sweden, 1943.

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Fischer, M.; Karlsson, M.; Nilsson, T. Effects of Compulsory Schooling on Mortality: Evidence from Sweden. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 3596-3618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10083596

Fischer M, Karlsson M, Nilsson T. Effects of Compulsory Schooling on Mortality: Evidence from Sweden. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2013; 10(8):3596-3618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10083596

Chicago/Turabian StyleFischer, Martin, Martin Karlsson, and Therese Nilsson. 2013. "Effects of Compulsory Schooling on Mortality: Evidence from Sweden" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10, no. 8: 3596-3618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10083596

APA StyleFischer, M., Karlsson, M., & Nilsson, T. (2013). Effects of Compulsory Schooling on Mortality: Evidence from Sweden. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(8), 3596-3618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10083596