Men’s Migration, Women’s Personal Networks, and Responses to HIV/AIDS in Mozambique

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Conceptual Framework

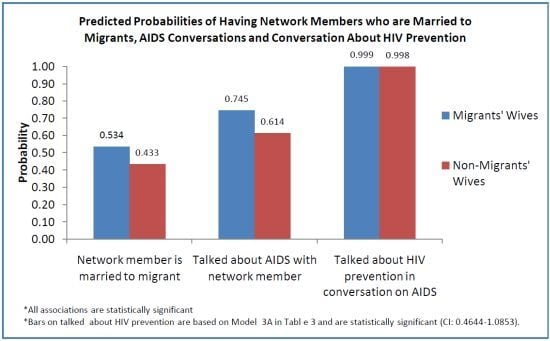

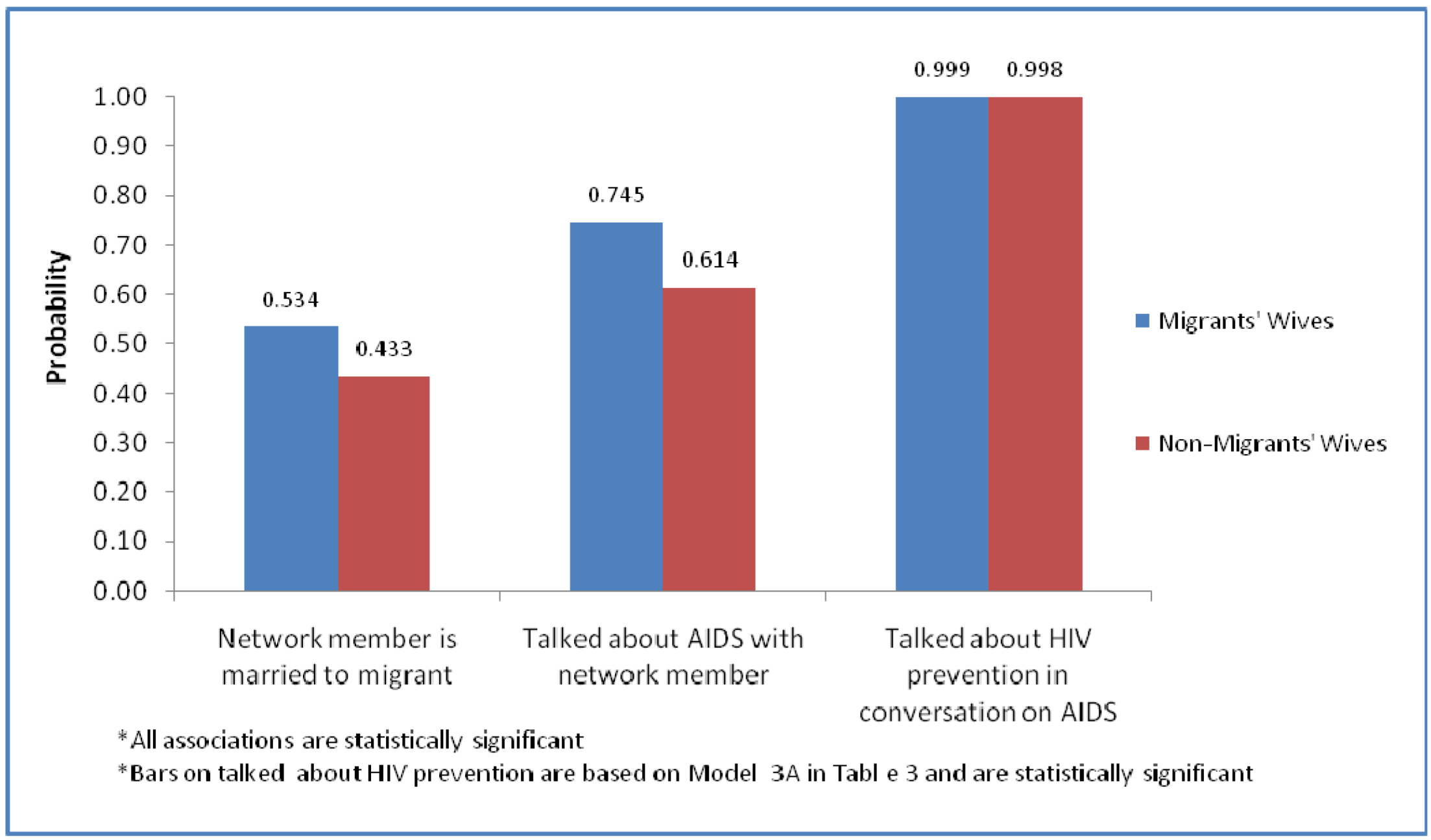

- H1: Migrants’ wives are more likely to have fellow migrants’ wives as personal network members than are non-migrants’ wives, net of other characteristics.

- H2: Migrants’ wives are more likely to use embedded resources within their networks to engage in communication about HIV/AIDS with members of their personal network than are non-migrants’ wives, net of other characteristics.

- H3: Migrants’ wives are more likely to use embedded resources within their networks to converse about HIV/AIDS with network members who are also migrants’ wives than with network members who are not migrants’ wives, net of other characteristics.

- H4: Migrants’ wives are more likely to use embedded resources within their networks to discuss HIV prevention in their conversations with network members compared to non-migrants’ wives, net of other characteristics.

- H5: Migrants’ wives are more likely to have been tested for HIV and to use HIV prevention if their network members are also migrants’ wives and have tested for HIV and used prevention, net of other characteristics.

4. Study Setting

5. Methods

5.1. Data

5.2. Measures

5.3. Statistical Model

6. Results

6.1. Descriptive Analysis

| Husband’s Labor Migration Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Migrant | Not a migrant | All | |

| Network member is married to migrant ** | 42.42 | 55.3 | 47.98 | |

| Network member is Kin or in-law | 37.99 | 36.31 | 37.12 | |

| Network member’s age relative to ego | ||||

| Older than ego | 52.45 | 50.41 | 51.37 | |

| Same as ego | 19.16 | 18.86 | 18.95 | |

| Younger than ego | 28.39 | 30.73 | 29.68 | |

| Religion | ||||

| Same as ego’s | 50.5 | 47.84 | 48.95 | |

| Other/No religion or don’t know | 49.5 | 52.16 | 51.05 | |

| Network member will loan ego money if in need | 86.91 | 85.18 | 85.96 | |

| Network member works outside the household | 12.95 | 12.16 | 12.47 | |

| Ever talked about AIDS with network member ** | 69.35 | 62.07 | 65.13 | |

| Network member uses at least one method of HIV prevention | 34.17 | 32.2 | 33.06 | |

| Network member had an AIDS test | 6.76 | 5.47 | 6.01 | |

| Ego’s uses at least one method of HIV prevention | 81.58 | 79.38 | 80.1 | |

| Ego had AIDS test | 18.2 | 16.77 | 17.34 | |

| Total | 42.93 | 57.07 | 100 | |

| N | 1,390 | 1,848 | 3,238 | |

| Husband’s Migration Status | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Themes | Migrant | Not a migrant | All |

| Need for Prevention | 92.22 * | 88.23 * | 90.07 |

| Known or Suspected AIDS Cases | 64.21 * | 59.55 * | 61.59 |

| Testing and Treatment of AIDS | 23.65 * | 19.97 * | 21.62 |

| Other themes | 4.99 | 4.81 | 4.89 |

6.2. Multivariate Analysis

| 1. Network member is married to migrant | 2. Talked about AIDS with network members | 3. Talked about HIV prevention in conversation on AIDS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2A | 2B | 3A | 3B | |||

| Labor migration | ||||||

| Migrant’s wife | 1.50 ** | 1.84 ** | 1.28 | 2.17 ** | 1.52 | |

| Worried of AIDS infection from spouse | 1.08 | 3.31 ** | 2.98 ** | 2.29 ** | 2.11 * | |

| Network member is married to migrant | 1.44 ** | 1.33 † | 1.19 | 1.06 | ||

| Network Resources | ||||||

| Kin | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.94 | ||

| Older than ego | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.01 | 1.01 | ||

| Younger than ego | 1.11 | 1.11 | 0.98 | 0.98 | ||

| Same religion as ego’s | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.10 | 1.10 | ||

| Network member would loan money | 1.19 | 1.17 | 1.32 | 1.30 | ||

| Network member works | 1.23 | 1.24 | 1.16 | 1.18 | ||

| Ego’s characteristics | ||||||

| Age (in years) | 0.98 * | 1.04 * | 1.04 * | 1.03 | 1.02 | |

| Number of living children | 0.98 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.060 * | 1.06 | |

| 1–4 years of school | 1.08 | 1.36 | 1.37 | 1.19 | 1.19 | |

| 5 or more years of school | 1.26 † | 2.65 ** | 2.71 ** | 1.74 * | 1.91 * | |

| Currently working | 0.83 † | 2.00 ** | 2.01 ** | 1.72 * | 1.73 * | |

| In polygynous union | 0.86 | 1.23 | 1.23 | 1.5 * | 1.50 * | |

| Resides with parents in-law | 1.03 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.04 | 1.04 | |

| Household material possession index | 1.09 † | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.02 | |

| Thatched roof | 0.86 † | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.94 | |

| Household own cattle | 1.04 | 1.12 | 1.13 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |

| Mainline church | 1.09 | 1.30 | 1.30 | 1.39 | 1.39 | |

| Zoinist/Pentecostal | 0.95 | 1.69 * | 1.69 * | 1.64 * | 1.64 | |

| Had talked to husband about AIDS | 1.15 | 9.77 ** | 9.82 ** | 8.785 ** | 8.81 ** | |

| Migrant’s wife*worried of AIDS infection from spouse | 1.37 | 1.29 | ||||

| Migrant’s wife*network member is married to migrant | 1.21 | 1.32 | ||||

| Generalized Chi-square | 2,922.0 | 1,263.7 | 1,261.00 | 1,390.0 | 1,387.33 | |

| Generalized Chi-square/DF | 0.91 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.44 | |

| N | 3,227 | 3,210 | 3,210 | 3,210 | 3,210 | |

| Ego’s Uses HIV Prevention | Ego has Tested for HIV | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Labor migration status | |||

| Migrant’s wife | 1.09 | 1.03 | |

| Worried of AIDS infection from spouse | 1.34 | 1.47 | |

| Network member is married to migrant | 0.76 † | 0.93 | |

| Network member uses HIV prevention | 4.92 ** | ||

| Network member has tested for HIV | 8.64 ** | ||

| Network Resources | |||

| Kin | 0.77 | 1.17 | |

| Older than ego | 0.93 | 0.89 | |

| Younger than ego | 1.01 | 0.99 | |

| Same religion as ego’s | 1.27 | 0.92 | |

| Network member would loan money | 1.35 | 0.96 | |

| Network member works | 1.13 | 1.11 | |

| Ego’s characteristics | |||

| Age (in years) | 1.01 | 0.96 * | |

| Number of living children | 0.96 | 1.17 * | |

| 1–4 years of school | 1.15 | 0.82 | |

| 5 or more years of school | 1.33 | 1.43 | |

| Currently working | 1.64 * | 0.72 | |

| In polygynous union | 0.75 | 1.11 | |

| Resides with parents in-law | 0.91 | 1.01 | |

| Household’s material possession index | 1.23 * | 1.18 | |

| Thatched roof | 1.30 | 1.07 | |

| Household owns cattle | 0.68 † | 1.04 | |

| Mainline church | 1.01 | 1.73 | |

| Zionist/Pentecostal | 1.09 * | 1.97 * | |

| [No religion] | 2.09 | 1.34 | |

| Had talked to husband about AIDS | 2.09 ** | 1.34 | |

| Migrant’s wife*network member is married to migrant*network member prevent HIV | 2.10 | ||

| Migrant’s wife*network member is married to migrant*network member Tested for HIV | 0.60 | ||

| Generalized Chi-square | 903.78 | 908.50 | |

| Generalized Chi-square/DF | 0.28 | 0.29 | |

| N | 3,210 | 3,210 | |

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of social capital. In The Handbook of Theory: Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J.G., Ed.; Greenwood Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi, I.; Subramanian, S.V.; Kim, D. Social Capital and Health; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N. Building a network theory of social capital. In Social Capital Theory and Research; Lin, N., Cook, K., Burt, R.S., Eds.; Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anarfi, J.K. Sexuality, migration and AIDS in Ghana—A socio-behavioral study. Health Trans. Rev. 1993, 3 (suppl.), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lurie, M.N.; Williams, B.G.; Zuma, K.; Mkaya-Mwamburi, D.; Garnett, G.P.; Sweat, M.D.; Gittelsohn, J.; Abdool Karim, S.S. The impact of migration on HIV-1 transmission in South Africa: A study of migrant and nonimmigrant men and their partners. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2003, 30, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agadjanian, V.; Menjívar, C. Talking about the epidemic of the millennium: Religion, informal communication, and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Soc. Probl. 2008, 55, 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helleringer, S.; Kohler, H.-P. Social networks, perception of risk, and changing attitudes towards HIV/AIDS: New evidence from a longitudinal study using fixed-effects analysis. Population 2005, 59, 265–282. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut, R.G.; Weeks, J.R. Unraveling a public health enigma: Why do immigrants experience superior perinatal health outcomes? Res. Sociol. Health Care 1996, 13B, 337–391. [Google Scholar]

- Coffee, M.; Lurie, M.N.; Garnett, G.P. Modeling the impact of migration on the HIV epidemic in South Africa. AIDS 2007, 21, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.R.; Marino, F. Social support and social structure: A descriptive epidemiology. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1994, 35, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I.; Kennedy, B.P.; Lochner, K.S.M.; Deborah, P.-S. Social capital, income inequality and mortality. Am. J. Public Health 1997, 87, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L.F. Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In Social Epidemiology; Berkman, L.F., Kawachi, I., Eds.; Oxford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 332–348. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. Am. Prospect. 1993, 13, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J. Democr. 1995, 6, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- House, J.S.; Landis, K.R.; Umberson, D. Social relationships and health. Science 1988, 241, 540–545. [Google Scholar]

- Haines, V.A.; Beggs, J.J.; Hurlbert, J.S. Contextualizing health outcomes: Do effects of networks structure differ for women and men? Sex. Roles 2008, 59, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A. Stress, coping and social support processes: Where are we? What next? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, Extra Issue, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregson, S.; Terceira, N.; Mushati, P.; Nyamukapa, C.; Campbell, C. Community group participation: Can it help young women to avoid HIV? An exploratory study of social capital and school education in Rural Zimbabwe. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 58, 2119–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronyk, P.M.; Harpham, T.; Busza, J.; Phetla, G.; Morison, L.A.; Hardreaves, J.R.; Kim, J.C.; Watts, C.H.; Porter, J.D. Can social capital be intentionally generated? A randomized trial from Rural South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Aguilar, J.P.; Bacchus, D.N.A. Migration, poverty and risk of HIV infection: An application of social capital theory. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2010, 20, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, K.N. Social capital, microfinance and the politics of development. Fem. Econ. 2002, 8, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Outline of a Theory of Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Kelly, M.P. Social and Cultural Capital in the Urban. Ghetto: Implications for the Economic Sociology of Immigration; Russell Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.P.; Christakis, N.A. Social networks and health. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 2008, 34, 405–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, M.N.; Williams, B.G.; Zuma, K.; Mkaya-Mwamburi, D.; Garnett, G.P.; Sweat, M.D.; Gittelsohn, J.; Abdool Karim, S.S. Who infects whom? HIV-1 concordance and discordance among migrant and non-migrant couples in South Africa. AIDS 2003, 17, 2245–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, M.J.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Cook, J.M. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, M.J.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Brashears, M.E. Social isolation in America: Changes in core discussion networks over two decades. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2006, 71, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabiku, S.T.; Agadjanian, V.; Sevoyan, A. Husbands labor migration and wives autonomy, Mozambique 2000–2006. Popul. Studies 2010, 64, 293–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agadjanian, V.; Arnaldo, C.; Cau, B. Health costs of wealth gains: Labor migration and perceptions of HIV/AIDS risks in Mozambique. Soc. Forces 2011, 89, 1097–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agadjanian, V.; Menjívar, C.; Cau, B. Economic Uncertainties, Social Strains, and HIV Risks: Exploring the Effects of Male Labor Migration on Rural Women in Mozambique. In How Migrants Impact their Homelands; Eckstein, S., Najam, A., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2013; (forthcoming). [Google Scholar]

- Joffe, H.; Begetta, N. Social representation of AIDS among Zambian Adolescents. J. Health Psychol. 2003, 8, 616–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.A. Changing HIV Risk Behavior: Practical Strategies; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Valente, T.W.; Watkins, S.C.; Jato, M.N.; van Der Straten, A.; Tsitsol, P.M. Social network associations with contraceptive use among Cameroonian women in voluntary associations. Soc. Sci. Med. 1997, 45, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S. Extra-Marital sexual partnerships and male friendships in Rural Malawi. Demogr. Res. 2010, 22, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Population Reference Bureau World Population Data Sheet 2012, Washington. Available online: http://www.prb.org/pdf12/2012-population-data-sheet_eng.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2013).

- UNAIDS Report on the Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic: July 2002. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/dataimport/pub/report/2002/brglobal_aids_ report_en_pdf_red_en.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2013).

- Ministry of Health of Mozambique, Relatório Sobre a Revisão dos Dados de Vigilância Epidemiologica do HIV – Ronda; Ministry of Health: Maputo, Mozambique, 2004.

- Ministry of Health, Inquérito Nacional de Prevalência, Riscos Comportamentais e Informação sobre o HIV e SIDA (INSIDA); Ministry of Health: Maputo, Mozambique, 2009.

- Adepoju, A. Continuity and changing configurations of migration to and from the republic of South Africa. Int. Migr. 2003, 41, 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Crush, J.; Raimundo, I.; Simelane, H.; Cau, B. Migration-Induced HIV and AIDS in Rural Mozambique and Swaziland. Southern African Migration Programme, 2010. Available online: http://www.queensu.ca/samp/sampresources/samppublications/policyseries/Acrobat53.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2013).

- Crush, J.; Jeeves, A.; Yudelman, D. South. Africa’s Labor Empire: A History of Black Migrancy. to the Gold Mines; CO Westview: Boulder, CO, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- First, R. Black Gold: the Mozambican Miner, Proletarian and Peasant; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- De Vletter, F. Migration and development in Mozambique: Poverty, inequality and survival. Devel. South. Afr. 2007, 24, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helleringer, S.; Kohler, H.-P.; Chimbiri, A. Characteristics of external/bridge relationships by partner type and location where sexual relationship took place. AIDS 2007, 21, 2560–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrito, P.B. From GLM to GLIMMIX—Which model to choose? In the 13th Annual Conference of the Southeast SAS Users Group, Portsmouth, VA, USA, 23–25 October 2005.

- Smith, R.B. Multilevel Modeling of Social Problems: A Causal Perspective; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, P.J.; Bons, T.A. Mate choice and friendship in twins: evidence for genetic similarity. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 16, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, R. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian, V. Informal Social Networks and Epidemic Prevention in a Third World Context: Cholera and HIV/AIDS Compared. In Advances in Medical Sociology, Social Networks and Health; Levy, J.A, Pescosolido, B.A., Eds.; JAI-Elsevier Science: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2002; Volume 8, pp. 201–221. [Google Scholar]

- Behrman, J.; Kohler, H.-P.; Watkins, S.C. Social networks, HIV/AIDs and risk perceptions. Demography 2007, 44, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Straten, A.; King, R.; Grinstead, O.; Serufilira, A.; Allen, S. Couple communication, sexual coercion and HIV risk reduction in Kigali, Rwanda. AIDS 1995, 9, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickman, R.L.; Lodico, M.; Diclemente, R.J.; Morris, R.; Baker, C.; Huscroft, S. Sexual Communication is associated with condom use by sexually active incarcerated adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 1994, 15, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, A.P.; Sayles, J.N.; Patel, V.A.; Remien, R.H.; Ortiz, D.; Szekers, G.; Coates, T. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: A review of literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS 2008, 22, S67–S79. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Avogo, W.; Agadjanian, V. Men’s Migration, Women’s Personal Networks, and Responses to HIV/AIDS in Mozambique. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 892-912. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10030892

Avogo W, Agadjanian V. Men’s Migration, Women’s Personal Networks, and Responses to HIV/AIDS in Mozambique. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2013; 10(3):892-912. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10030892

Chicago/Turabian StyleAvogo, Winfred, and Victor Agadjanian. 2013. "Men’s Migration, Women’s Personal Networks, and Responses to HIV/AIDS in Mozambique" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10, no. 3: 892-912. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10030892

APA StyleAvogo, W., & Agadjanian, V. (2013). Men’s Migration, Women’s Personal Networks, and Responses to HIV/AIDS in Mozambique. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(3), 892-912. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10030892