Genome Mining and Molecular Networking-Targeted Discovery of Siderophores with Plant Growth-Promoting Activities from the Marine-Derived Streptomonospora nanhaiensis 12A09T

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

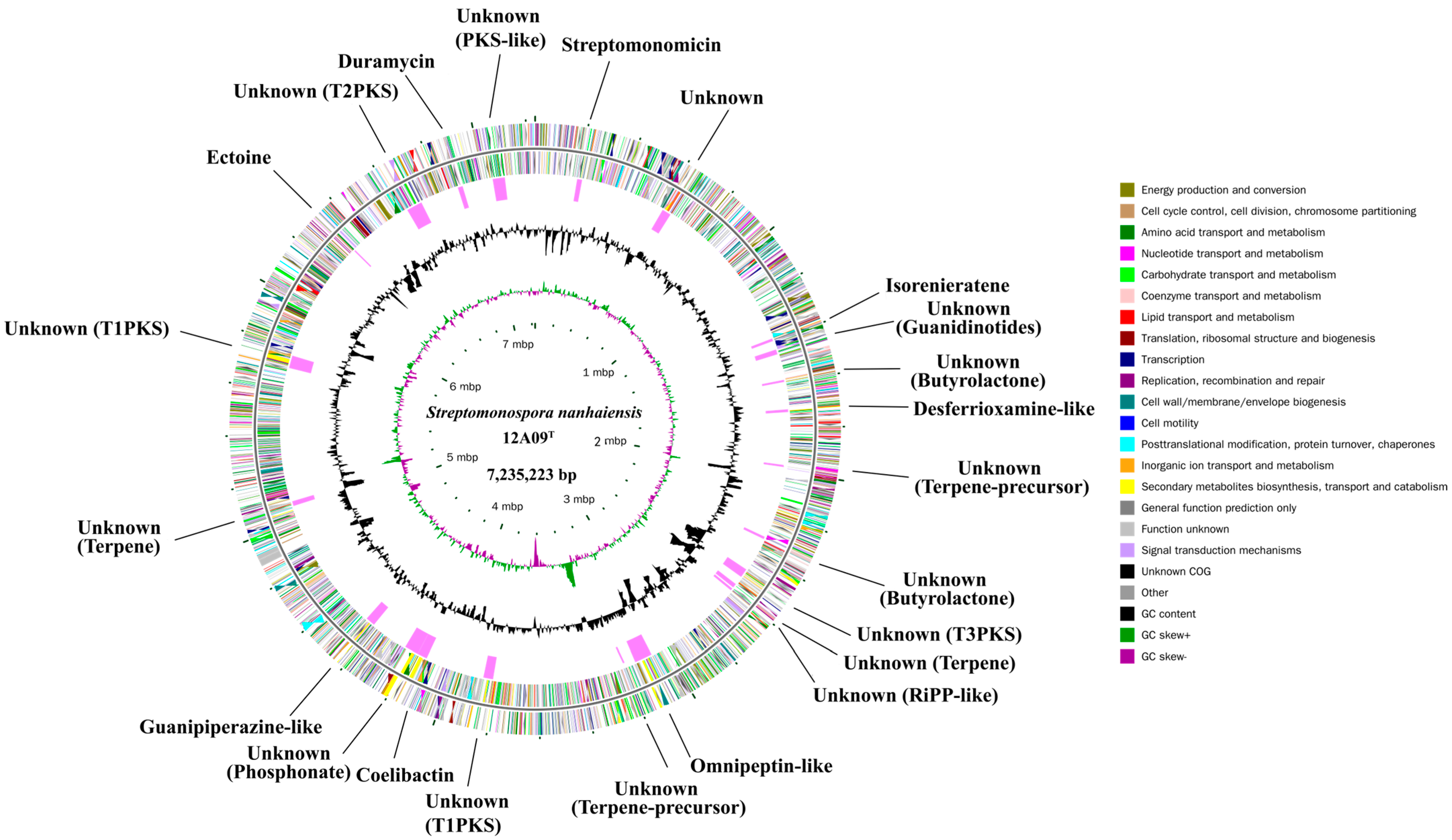

2.1. Complete Genome Features of S. Nanhaiensis 12A09T

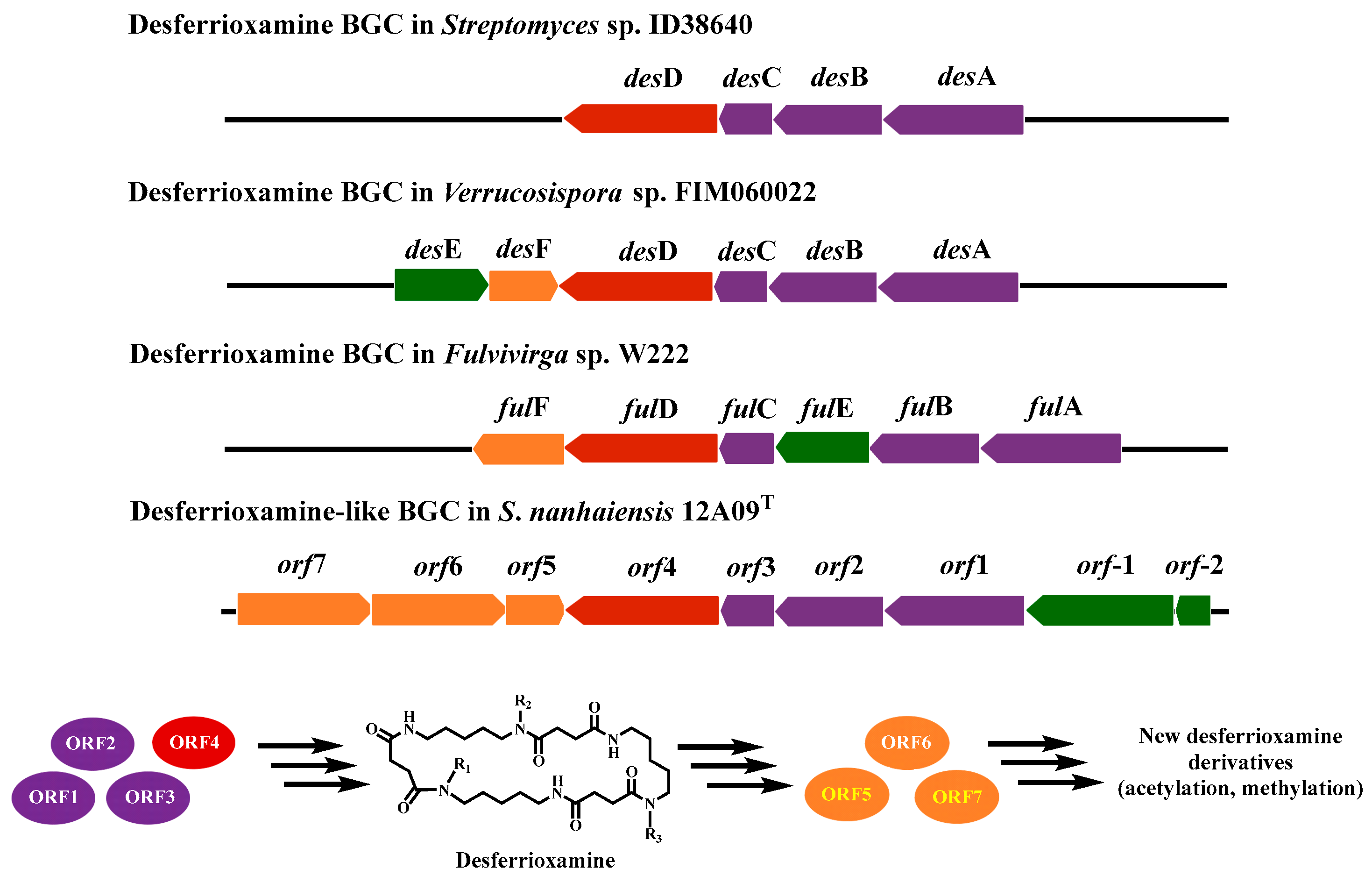

2.2. Genome Mining of BGCs

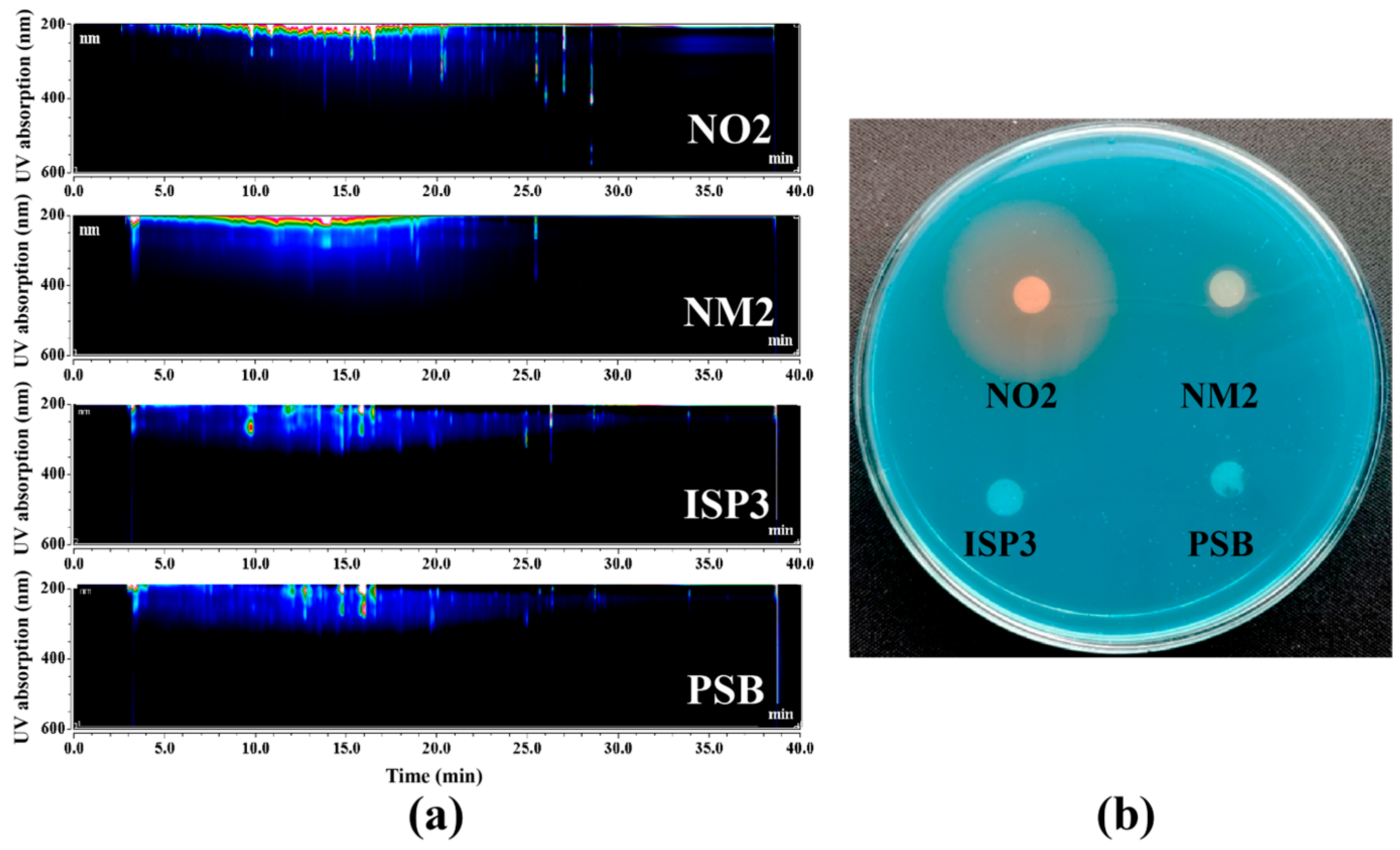

2.3. Culture Regulation for Activating the Silent Siderophore BGC

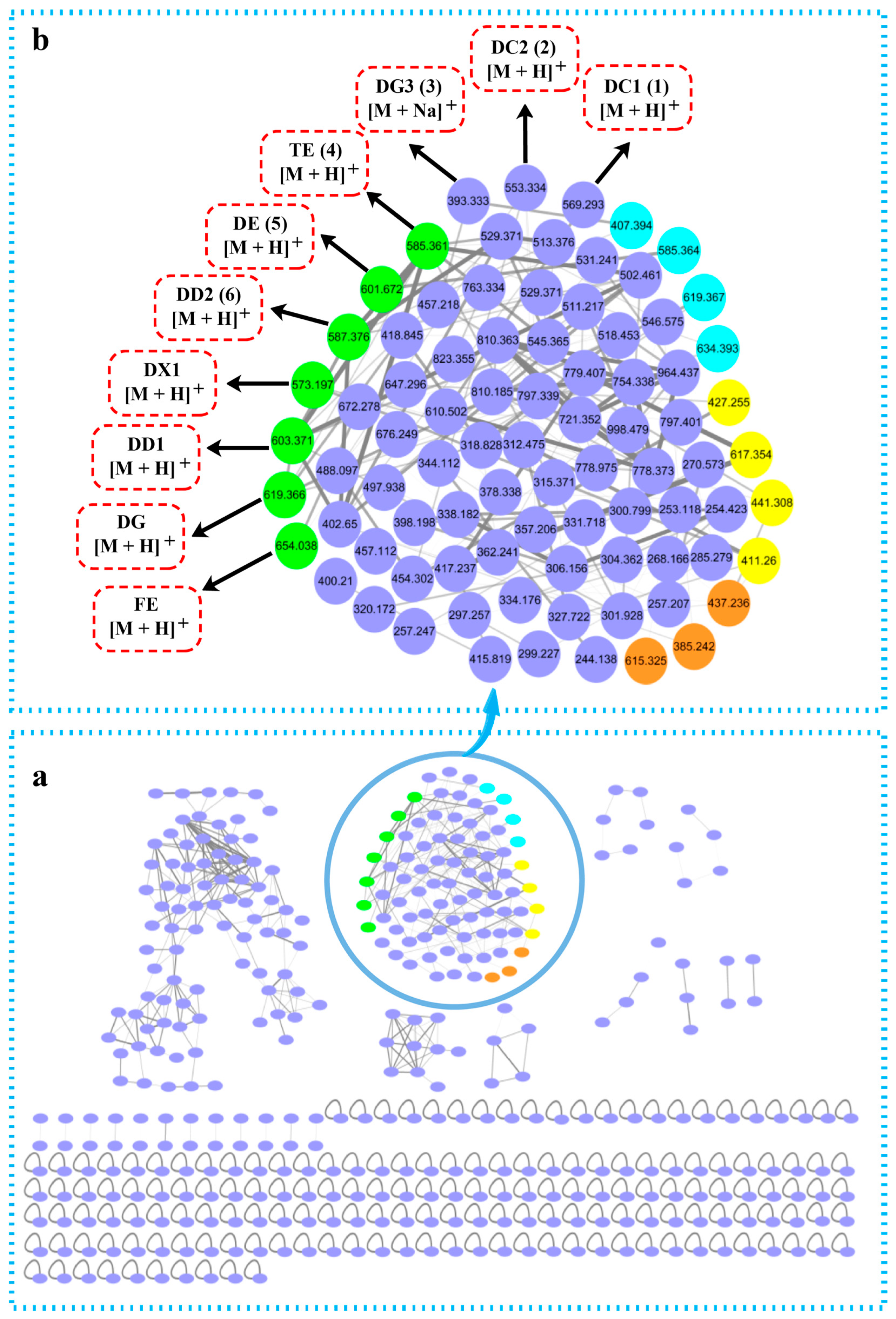

2.4. Molecular Networking Analysis of Siderophore Extracts

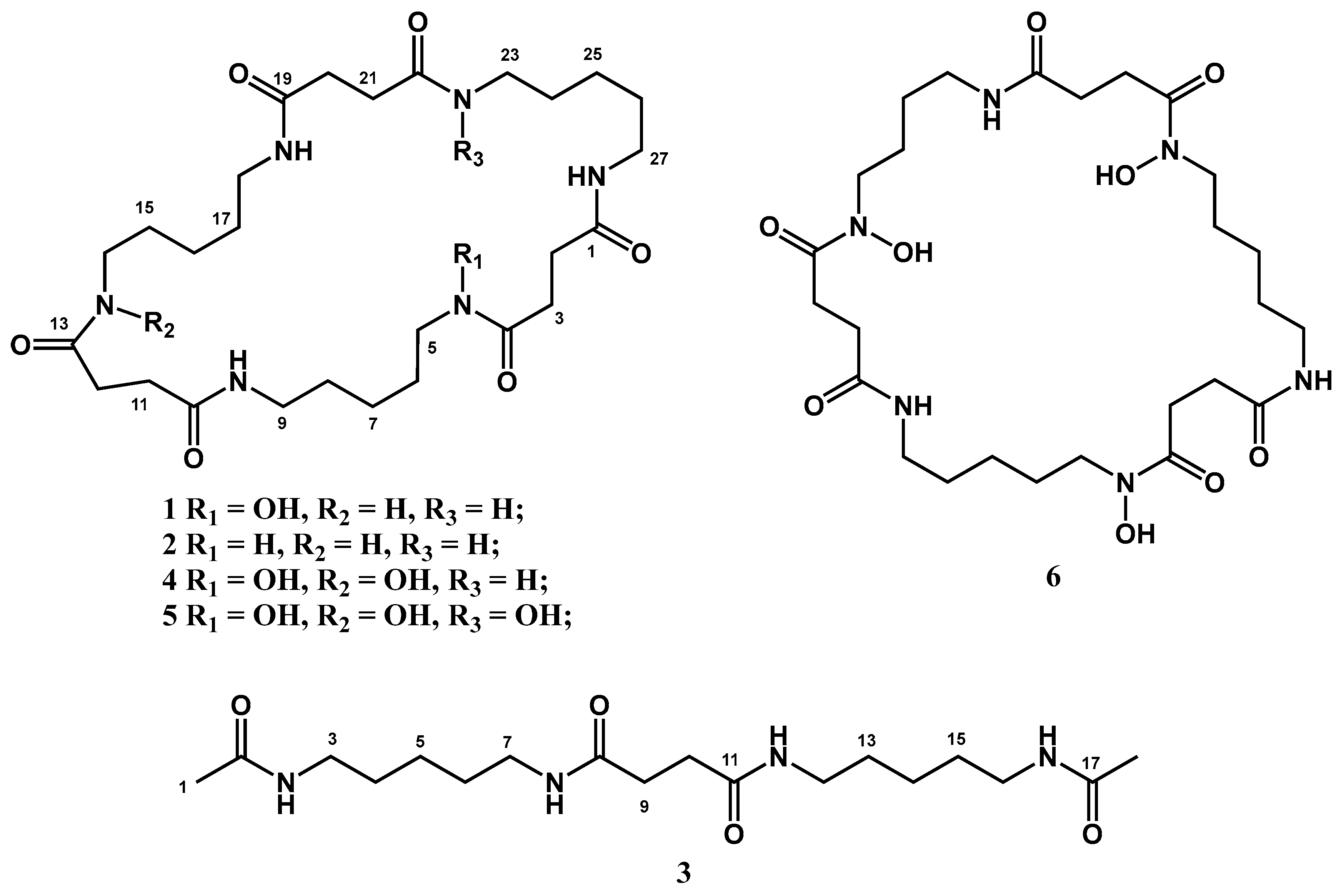

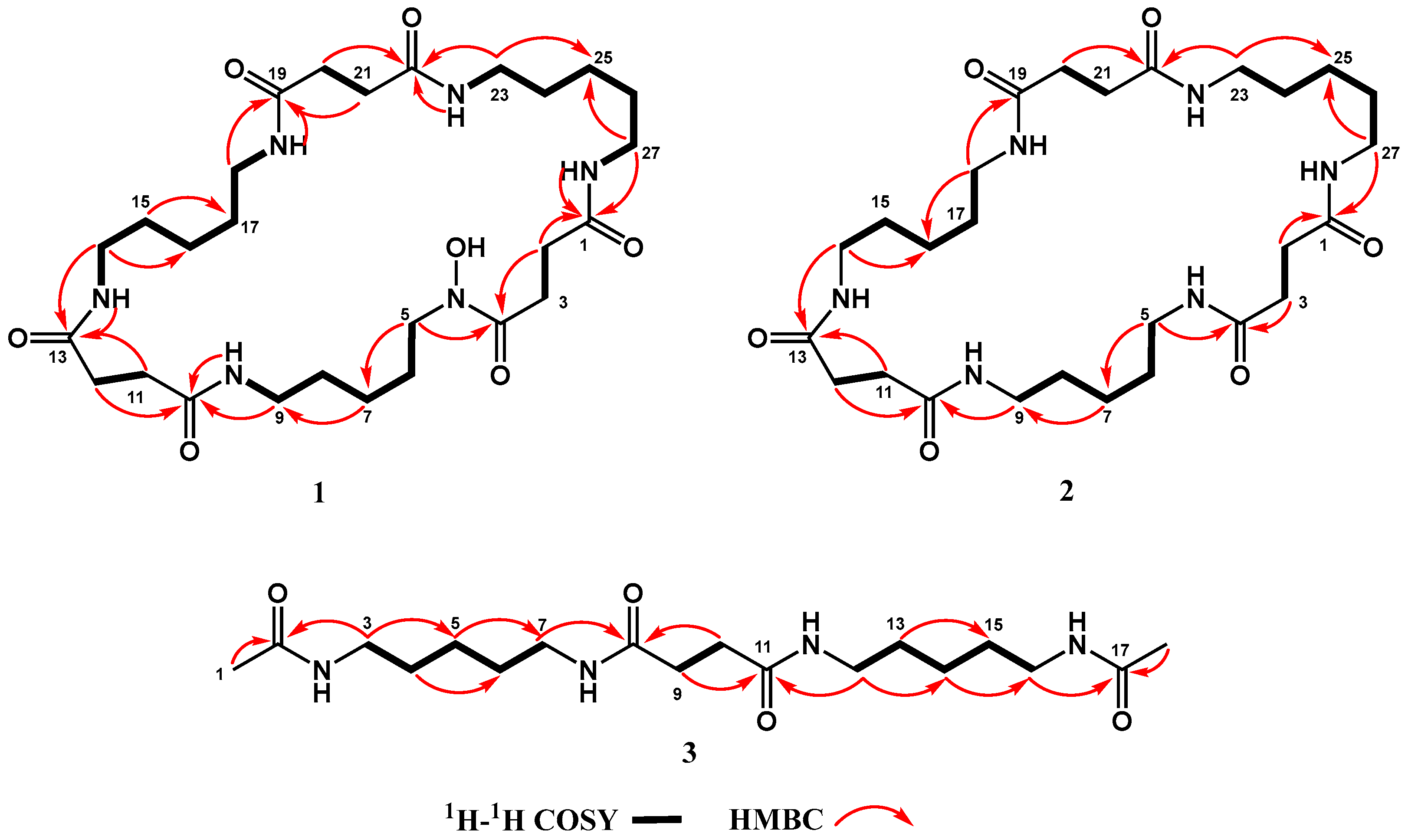

2.5. Structural Elucidation

2.6. Ferric Iron-Chelating Activity

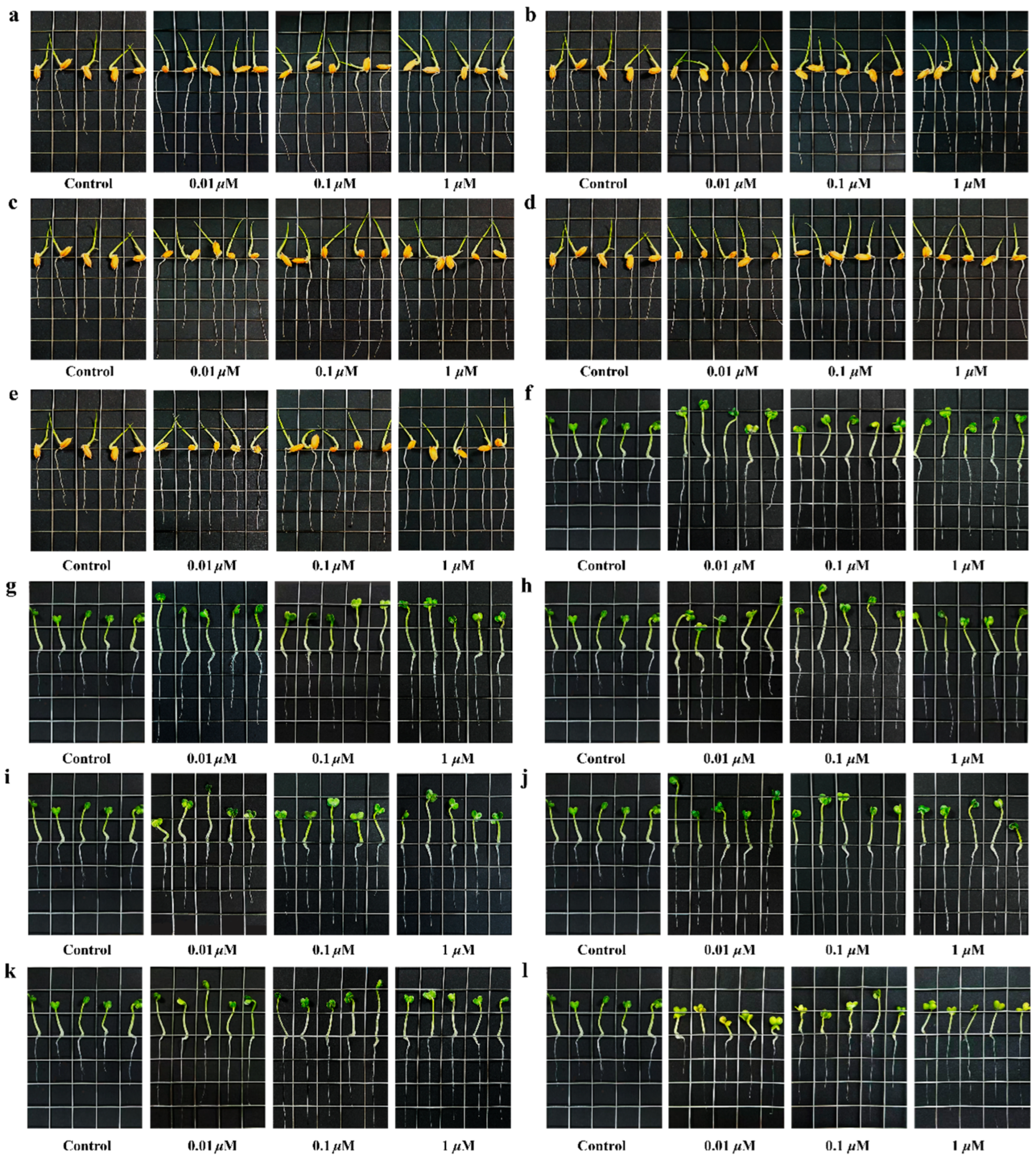

2.7. Bioassay of Plant Growth Regulatory Activity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

3.2. Actinomycete Strain

3.3. Genome Sequencing and BGCs Mining

3.4. Culture Regulation for Activating the Siderophore BGC

3.5. CAS Plate Assay

3.6. Fermentation and Extraction

3.7. LC-MS/MS Molecular Networking Analysis

3.8. HPLC-DAD and Bioactivity Guided Isolation and Purification

3.9. Ferric Iron-Chelating Activity

3.10. Bioassay of Plant Growth Regulatory Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dobroslavska, P.; Silva, M.L.; Vicente, F.; Pereira, P. Mediterranean dietary pattern for healthy and active aging: A narrative review of an integrative and sustainable approach. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.X.; Zhang, M.M.; Li, L.; Wang, X.J.; Li, S.S.; Xiang, W.S. Development and application of the novel plant growth regulator guvermectin: A perspective. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 8365–8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.X.; Bai, L.; Cao, P.; Li, S.S.; Huang, S.X.; Wang, J.D.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, J.W.; Song, J.; et al. Novel plant growth regulator guvermectin from plant growth promoting rhizobacteria boosts biomass and grain yield in rice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 16229–16240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gong, D.H.; Zhao, K.J.; Chen, D.Y.; Dong, Y.W.; Gao, Y.Y.; Wang, Q.; Hao, G.F. Research and development trends in plant growth regulators. Adv. Agrochem. 2024, 3, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.R.; Copp, B.R.; Grkovic, T.; Keyzers, R.A.; Prinsep, M.R. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2025, 42, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Qi, L.; Xu, M.H.; Li, W.Y.; Liu, N.; He, X.L.; Zhang, Y.X. Anti-Agrobacterium tumefactions sesquiterpene derivatives from the marine-derived fungus Trichoderma effusum. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1446283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.G.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M.Z.; Ding, G.; Jia, C.G.; Qin, J.C.; Guo, L.P. Marine natural products: The important resource of biological insecticide. Chem. Biodivers. 2021, 18, e2001020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.C.; Cao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Zhao, J.R.; Zhang, Q.; Ji, A.G.; Song, S.L. Advances in research on the bioactivity of alginate oligosaccharides. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.G.; Konhauser, K.O. Iron in earth surface systems: A major player in chemical and biological processes. Elements 2011, 7, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.W.; Guo, Y.Q.; Wu, Q.H.; Wang, W.; Pan, J.W.; Chen, M.H.; Jiang, H.; Yin, Q.J.; Zhang, G.Y.; Wei, B.; et al. Discovery of new siderophores from a marine Streptomycetes sp. via combined metabolomics and analysis of iron-chelating activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 6584–6593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hider, R.C.; Kong, X.L. Chemistry and biology of siderophores. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010, 27, 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, C.A.R.; Siringan, M.A.T.; Relucio-San Diego, M.A.C.V. Multiple plant growth–promoting activities exhibited by root associated bacteria isolated from bamboo and corn. Int. J. Microbiol. 2025, 2025, 6374935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Kuerban, Z.; Jiang, R.; He, F.X.; Hu, X.; Xu, Y.C.; Dong, C.X.; Shen, Q.R. The isolation, identification, whole-genome sequencing of Trichoderma brevicompactum TB2 and its effects on plant growth-promotion. Plant Soil 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithyapriya, S.; Sundaram, L.; Eswaran, S.U.D.; Perveen, K.; Alshaikh, N.A.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Mastinu, A. Purification and characterization of desferrioxamine B of Pseudomonas fuorescens and its application to improve oil content, nutrient uptake, and plant growth in peanuts. Microb. Ecol. 2024, 87, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.X.; Shi, L.S.; Shi, H.M.; Ye, J.R. Characterization of the Priestia megaterium ZS-3 siderophore and studies on its growth promoting effects. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.Q. Design and prospects of an efficient mining pipeline for microbial natural products in the post-genome era. J. Microbiol. 2022, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov, R.L.; Galperin, M.Y.; Natale, D.A.; Koonin, E.V. The COG database: A tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosio, M.; Gaspari, E.; Iorio, M.; Pessina, S.; Medema, M.H.; Bernasconi, A.; Simone, M.; Maffioli, S.I.; Ebright, R.H.; Donadio, S. Analysis of the pseudouridimycin biosynthetic pathway provides insights into the formation of C-nucleoside antibiotics. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018, 25, 540–549.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.J.; Zhou, H.B.; Zhong, G.N.; Huo, L.J.; Tang, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.M.; Bian, X.Y. Genome mining and biosynthesis of primary amine-acylated desferrioxamines in a marine gliding bacterium. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 939–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Peng, F.; Wang, C.X.; Xie, Y.; Lin, R.; Fang, Z.K.; Sun, F.; Lian, T.Y.; Jiang, H. FW0622, a new siderophore isolated from marine Verrucosispora sp. by genomic mining. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 3082–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.X.; Li, H.L. Structure, function, and biosynthesis of siderophores produced by Streptomyces species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 4425–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzis, J.A.; Ingrey, S.D.; Chau, R.; Simon, Y.; Neilan, B.A. Genome-guided discovery of natural products and biosynthetic pathways from Australia’s untapped microbial megadiversity. Aust. J. Chem. 2016, 69, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.Y.S.; Graziani, E.; Waters, B.; Pan, W.B.; Li, X.; McDermott, J.; Meurer, G.; Saxena, G.; Andersen, R.J.; Davies, J. Novel natural products from soil DNA libraries in a Streptomycete host. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 2401–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S.; Shin, H.J.; Jang, K.H.; Kim, T.S.; Oh, K.B.; Jongheon Shin, J. Cyclic peptides of the nocardamine class from a marine-derived bacterium of the genus Streptomyces. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 623–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Kanoh, K.; Adachi, K.; Matsuda, S.; Shizuri, Y. Tenacibactins A–D, hydroxamate siderophores from a marine-derived bacterium, Tenacibaculum sp. A4K-17. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.F.; Pan, H.Q.; He, J.; Zhang, X.M.; Zhang, Y.G.; Klenk, H.P.; Hu, J.C.; Li, W.J. Description of Streptomonospora sediminis sp. nov. and Streptomonospora nanhaiensis sp. nov., and reclassification of Nocardiopsis arabia Hozzein & Goodfellow 2008 as Streptomonospora arabica comb. nov. and emended description of the genus Streptomonospora. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 4447–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Vader, L.; Szenei, J.; Reitz, Z.L.; Augustijn, H.E.; Cediel-Becerra, J.D.D.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Koetsier, R.A.; Williams, S.E.; et al. antiSMASH 8.0: Extended gene cluster detection capabilities and analyses of chemistry, enzymology, and regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, W32–W38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwyn, B.; Neilands, J.B. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 160, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, M.C.; Maclean, B.; Burke, R.; Amodei, D.; Ruderman, D.L.; Neumann, S.; Gatto, L.; Fischer, B.; Pratt, B.; Egertson, J.; et al. A cross-platform toolkit for mass spectrometry and proteomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 918–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.X.; Carver, J.J.; Phelan, V.V.; Sanchez, L.M.; Garg, N.; Peng, Y.; Nguyen, D.D.; Watrous, J.; Kapono, C.A.; Luzzatto-Knaan, T.; et al. Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.J.; Wang, Z.; Han, J.; Su, S.H.; Gong, Y.X.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, N.H.; Wang, J.; Feng, L. Sativene sesquiterpenoids from the plant endophytic fungus Bipolaris victoriae S27 and their potential as plant-growth regulators. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 2598–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clusters | Type | From | To | Biosynthetic Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | Lassopeptide | 191,959 | 214,488 | Streptomonomicin |

| Cluster 2 | T2PKS | 605,576 | 653,305 | Unknown |

| Cluster 3 | Terpene | 1,381,481 | 1,407,212 | Isorenieratene |

| Cluster 4 | Guanidinotides | 1,441,572 | 1,464,125 | Unknown |

| Cluster 5 | Butyrolactone | 1,583,381 | 1,594,478 | Unknown |

| Cluster 6 | Siderophore | 1,710,310 | 1,740,625 | Desferrioxamine-like |

| Cluster 7 | Terpene-precursor | 1,948,404 | 1,969,495 | Unknown |

| Cluster 8 | Butyrolactone | 2,314,592 | 2,325,629 | Unknown |

| Cluster 9 | T3PKS | 2,485,075 | 2,526,133 | Unknown |

| Cluster 10 | Terpene | 2,566,315 | 2,587,691 | Unknown |

| Cluster 11 | RiPP-like | 2,592,565 | 2,602,861 | Unknown |

| Cluster 12 | NRPS | 3,068,416 | 3,150,338 | Omnipeptin-like |

| Cluster 13 | Terpene-precursor | 3.217,990 | 3,240,236 | Unknown |

| Cluster 14 | T1PKS | 3,809,298 | 3,855,021 | Unknown |

| Cluster 15 | NRPS | 4,127,061 | 4,178,721 | Coelibactin |

| Cluster 16 | Phosphonate | 4,383,958 | 4,394,830 | Unknown |

| Cluster 17 | NRPS-like | 4,411,046 | 4,454,201 | Guanipiperazine A/B-like |

| Cluster 18 | Terpene | 5,071,300 | 5,092,994 | Unknown |

| Cluster 19 | T1PKS | 5,706,685 | 5,764,401 | Unknown |

| Cluster 20 | Ectoine | 6,320,017 | 6,330,418 | Ectoine |

| Cluster 21 | T2PKS | 6,626,639 | 6,699,116 | Unknown |

| Cluster 22 | Lanthipeptide-class-iv | 6,878,044 | 6,900,620 | Duramycin |

| Cluster 23 | PKS-like | 7,053,968 | 7,096,753 | Unknown |

| Protein | Size (aa) | Proposed Function | Accession | Identities | Positives | Homologous Protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF-1 | 577 | Major facilitator superfamily transporter | XKK40617.1 | 99% | 99% | |

| ORF-2 | 186 | TetR family transcriptional regulator | GAA1444975.1 | 98% | 98% | |

| ORF1 | 547 | L-2, 4-diaminobutyrate decarboxylase | SFL00654.1 | 67% | 75% | DesA |

| ORF2 | 482 | Lysine/ornithine N-monooxygenase | XKK40621.1 | 99% | 99% | DesB |

| ORF3 | 206 | N-acetyltransferase | SIO88002.1 | 69% | 76% | DesC |

| ORF4 | 644 | Siderophore biosynthesis protein | MEU1626482.1 | 71% | 81% | DesD |

| ORF5 | 267 | Methyltransferase | XKK42002.1 | 94% | 94% | |

| ORF6 | 538 | Acyl-CoA synthetase | SHJ64988.1 | 80% | 85% | |

| ORF7 | 547 | Acyl-CoA transferase | SIO85325.1 | 73% | 77% |

| Observed Mass Peak (m/z) | Molecular Formula | Assignment | Post-Modification |

|---|---|---|---|

| 393.333 [M + Na]+ | C18H34N4O4 | Desferrioxamine G3 (3) | |

| 553.334 [M + H]+ | C27H48N6O6 | Desferrioxamine C2 (2) | |

| 569.293 [M + H]+ | C27H48N6O7 | Desferrioxamine C1 (1) | |

| 573.197 [M + H]+ | C25H44N6O9 | Desferrioxamine X1 | |

| 585.361 [M + H]+ | C27H48N6O8 | Terragine E (4) | |

| 587.376 [M + H]+ | C26H46N6O9 | Deferrioxamine D2 (6) | |

| 601.672 [M + H]+ | C27H48N6O9 | Desferrioxamine E (5) | |

| 603.370 [M + H]+ | C27H50N6O9 | Desferrioxamine D1 | |

| 619.366 [M + H]+ | C27H50N6O10 | Desferrioxamine G | |

| 654.038 [M + H]+ | C27H45FeN6O9 | Ferrioxamine E | |

| 411.260 [M − H]− | C20H36N4O5 | Desferrioxamine G3 (3) + acetyl | Acetylation |

| 427.255 [M − H]− | C19H32N4O7 | Avaroferrin + acetyl | Acetylation |

| 441.308 [M − H]− | C20H34N4O7 | Bisucaberin + acetyl | Acetylation |

| 617.354 [M + Na]+ | C29H50N6O7 | Desferrioxamine C2 (2) + acetyl | Acetylation |

| 385.242 [M + H]+ | C19H36N4O4 | Desferrioxamine G3 (3) + CH3 | Methylation |

| 437.236 [M + Na]+ | C19H34N4O6 | Bisucaberin + CH3 | Methylation |

| 615.325 [M + H]+ | C28H50N6O9 | Desferrioxamine E (5) + CH3 | Methylation |

| 407.394 [M + Na]+ | C18H32N4O4 | Desferrioxamine G3 (3) − 2H | Oxidation |

| 585.364 [M + H]+ | C27H48N6O8 | Desferrioxamine C1 (1) + O | Oxidation |

| 619.367 [M + H]+ | C27H50N6O10 | Desferrioxamine D1 + O | Oxidation |

| 634.393 [M + NH4]+ | C27H48N6O10 | Desferrioxamine E (5) + O | Oxidation |

| Position | 1 * | 2 # | 3 # | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH (J in Hz) | δC, Type | δH (J in Hz) | δC, Type | δH (J in Hz) | δC, Type | |

| 1 | 171.1 C | 174.6 C | 1.92 s a | 22.5 CH3 | ||

| 2 | 2.26 m a | 29.9 CH2 | 2.47 s a | 32.5 CH2 | 173.2 C | |

| 3 | 2.58 m | 27.5 CH2 | 2.47 s a | 32.5 CH2 | 3.15 m b | 40.3 CH2 |

| 4 | 172.1 C | 174.6 C | 1.51 m c | 30.0 CH2 | ||

| 5 | 3.45 m | 46.8 CH2 | 3.17 t (6.7) b | 40.1 CH2 | 1.35 m d | 25.2 CH2 |

| 6 | 1.48 m | 25.8 CH2 | 1.51 m c | 29.9 CH2 | 1.51 m c | 30.0 CH2 |

| 7 | 1.20 m b | 23.1 CH2 | 1.35 m d | 25.0 CH2 | 3.15 m b | 40.3 CH2 |

| 8 | 1.34 m c | 28.7 CH2 | 1.51 m c | 29.9 CH2 | 174.5 C | |

| 9 | 2.98 m d | 38.2 CH2 | 3.17 t (6.7) b | 40.1 CH2 | 2.45 s e | 32.3 CH2 |

| 10 | 171.2 C | 174.6 C | 2.45 s e | 32.3 CH2 | ||

| 11 | 2.26 m a | 31.0 CH2 | 2.47 s a | 32.5 CH2 | 174.5 C | |

| 12 | 2.26 m a | 31.0 CH2 | 2.47 s a | 32.5 CH2 | 3.15 m b | 40.3 CH2 |

| 13 | 171.4 C | 174.6 C | 1.51 m c | 30.0 CH2 | ||

| 14 | 2.98 m d | 38.3 CH2 | 3.17 t (6.7) b | 40.1 CH2 | 1.35 m d | 25.2 CH2 |

| 15 | 1.34 m c | 28.7 CH2 | 1.51 m c | 29.9 CH2 | 1.51 m c | 30.0 CH2 |

| 16 | 1.20 m b | 23.5 CH2 | 1.35 m d | 25.0 CH2 | 3.15 m b | 40.3 CH2 |

| 17 | 1.34 m c | 28.7 CH2 | 1.51 m c | 29.9 CH2 | 173.2 C | |

| 18 | 2.98 m d | 38.2 CH2 | 3.17 t (6.7) b | 40.1 CH2 | 1.92 s a | 22.5 CH3 |

| 19 | 171.3 C | 174.6 C | ||||

| 20 | 2.26 m a | 31.0 CH2 | 2.47 s a | 32.5 CH2 | ||

| 21 | 2.26 m a | 31.0 CH2 | 2.47 s a | 32.5 CH2 | ||

| 22 | 171.3 C | 174.6 C | ||||

| 23 | 2.98 m d | 38.3 CH2 | 3.17 t (6.7) b | 40.1 CH2 | ||

| 24 | 1.34 m c | 28.7 CH2 | 1.51 m c | 29.9 CH2 | ||

| 25 | 1.20 m b | 23.5 CH2 | 1.35 m d | 25.0 CH2 | ||

| 26 | 1.34 m c | 28.7 CH2 | 1.51 m c | 29.9 CH2 | ||

| 27 | 2.98 m d | 38.2 CH2 | 3.17 t (6.7) b | 40.1 CH2 | ||

| -NH | 7.72 s | |||||

| N-OH | 9.58 s | |||||

| Compound | Oryza sativa | Brassica campestris | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 μM | 0.1 μM | 0.01 μM | 1 μM | 0.1 μM | 0.01 μM | |

| 1 | 4.2 ± 0.2 *** | 4.2 ± 0.2 *** | 3.8 ± 0.4 ** | 3.3 ± 0.2 *** | 2.9 ± 0.3 *** | 2.5 ± 0.2 *** |

| 2 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.1 *** | 2.7 ± 0.5 *** | 2.7 ± 0.3 *** |

| 3 | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.3 *** | 2.8 ± 0.3 *** | 2.2 ± 0.3 *** |

| 4 | 3.8 ± 0.3 ** | 3.6 ± 0.2 * | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.3 *** | 2.4 ± 0.3 *** | 2.1 ± 0.2 *** |

| 5 | 4.2 ± 0.3 *** | 4.2 ± 0.3 *** | 4.1 ± 0.2 *** | 3.3 ± 0.3 *** | 3.0 ± 0.4 *** | 2.9 ± 0.4 *** |

| 6 | 4.0 ± 0.3 *** | 3.9 ± 0.3 *** | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.3 *** | 2.8 ± 0.4 *** | 2.7 ± 0.4 *** |

| Gibberellin | 4.3 ± 0.2 *** | 4.2 ± 0.3 *** | 4.1 ± 0.3 *** | 3.4 ± 0.3 *** | 3.0 ± 0.5 *** | 2.8 ± 0.2 *** |

| Blank control | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bai, Y.; Gao, W.; Zhao, W.; Arishi, A.A.; Shang, Z.; Hu, J.; Pan, H. Genome Mining and Molecular Networking-Targeted Discovery of Siderophores with Plant Growth-Promoting Activities from the Marine-Derived Streptomonospora nanhaiensis 12A09T. Mar. Drugs 2026, 24, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010007

Bai Y, Gao W, Zhao W, Arishi AA, Shang Z, Hu J, Pan H. Genome Mining and Molecular Networking-Targeted Discovery of Siderophores with Plant Growth-Promoting Activities from the Marine-Derived Streptomonospora nanhaiensis 12A09T. Marine Drugs. 2026; 24(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Yan, Weixian Gao, Wendian Zhao, Amr A. Arishi, Zhuo Shang, Jiangchun Hu, and Huaqi Pan. 2026. "Genome Mining and Molecular Networking-Targeted Discovery of Siderophores with Plant Growth-Promoting Activities from the Marine-Derived Streptomonospora nanhaiensis 12A09T" Marine Drugs 24, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010007

APA StyleBai, Y., Gao, W., Zhao, W., Arishi, A. A., Shang, Z., Hu, J., & Pan, H. (2026). Genome Mining and Molecular Networking-Targeted Discovery of Siderophores with Plant Growth-Promoting Activities from the Marine-Derived Streptomonospora nanhaiensis 12A09T. Marine Drugs, 24(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/md24010007