“Our Work, Our Health, No One’s Concern”: Domestic Waste Collectors’ Perceptions of Occupational Safety and Self-Reported Health Issues in an Urban Town in Ghana

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Setting

Ethical Consideration

2.2. Population

2.3. Data Sampling and Collection Procedures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Background of Study Participants

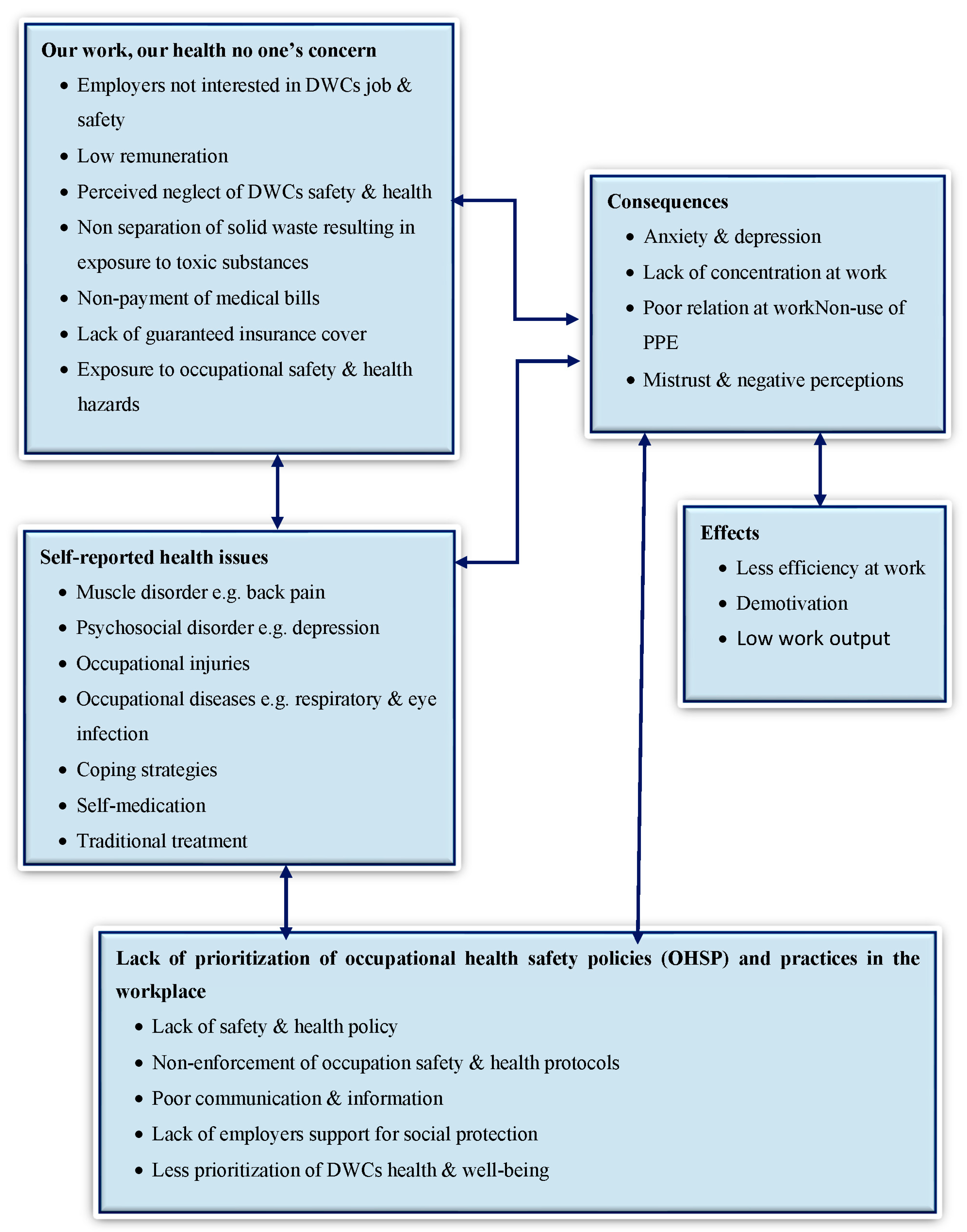

3.1.1. Emergent Theme 1: “Our Work, Our Health, No One’s Concern”

“As waste collectors, our concern is our health. For them (employers), our work, our health, is not their concern. All that they are interested in is the streets are clean every morning. Nothing else.”(Female FGD participant from company B)

“Our work, our health, no one’s concern, but for us (waste collectors). If you do not provide adequate protection and safety for yourself, you will lose your job and be in a poor state of health.”(Male IDI discussant from company A)

“Hhhmm our health is indeed in our hands. We encounter different kinds of waste daily, from human to animal waste, solid and liquid. Most of these wastes are always at an advanced stage of decomposition. Depending on how well you are dressed (in PPE), you are always at risk… hmmm.”(Female FGD participant from company B)

“Our waste is not sorted into various compartments. That is a major health threat in this job, where we encounter any kind and type of waste. So our health is really in our hands.”(Female IDI participant from company A)

“Before you get to work, even if you are not provided with the right tools to protect yourself, you will have to get that to stay safe”(Female IDI participant from company B)

“The company does not care about your health. I have been in this job for 7 years now and I know how to reduce the risk associated with it. My health is my concern. Otherwise, I would have left this job many years ago.”(Male IDI participant from company A)

3.1.2. Emergent Theme 2: Self-Reported Health Issues and Occupational Safety Coping Strategies among DWCs

‘’I have never known sickness or ill-health, my previous job as a gardener was less of a health burden, now I suffer from severe back pain because of the long hours under the sun picking and cleaning the markets.’’(Male FGD participant from company A)

‘’Over the last 5 years, my health has worsened so much, a lot of the work requires manual and intensive labor here. I have never had a skin disease, but today, I visit the clinic almost every month because I constantly suffer from irritations on my skin…”(Female IDI participant from company B)

“We have no health insurance to meet any medical emergency that may arise from this work, so we don’t go to the clinic or hospital. Every day we have so many health issues that can happen when you are at work. So, we deal with it with the drugs we purchase from drug peddlers or the drug shops close by.”(Male FGD participant, Company B)

“I feel stressed, and I am unable to perform my duties at an optimal level. Sometimes I find it very difficult to come to work, other times I feel like giving up on this job or to talk to someone about my problems but no one is near to listen.”(Female IDI discussant, company A)

“You see this bag; I have everything inside to deal with any hurt or accidents while am on the job. Ask anyone, they will show one or more first aid items they have in their pockets too…. it’s always safe and good to take your health on the streets into your own hands.”(Male IDI participant, company B)

3.1.3. Emergent Theme 3: Lack of Prioritization of Occupational Health and Safety Policies (OHSP) and Practices in the Workplace

“Hmmm, the company has good policies for workers, we only hear it but do not benefit from it. These policies are only spoken of in good meetings outside the company. We hope that we too will be taken care of one day and we will benefit from the policies.”(Female FGD participant, company A)

“For the policies benefitting our health, hmmm, we are yet to see that. For policies, we hear about it. We have been told, just that we are yet to feel it. I think they must re-prioritize and put our health needs first because it is currently low or non-existent in the workplace. Something needs to be done for us.”(Female IDI participant, company B)

“I use to work for a company in Tema before coming to work here, I think government officers used to come regularly to monitor and even sometimes interview us. So, the company was serious about the health of workers. Ever since I joined this waste company, I have not seen any government official coming to supervise what we do, not alone how workers’ welfare and health is. Government must do that to help us.”(Male FGD participant, company B)

“You see the gloves and nose mask am wearing (pointing to her hands and nose), I purchased these myself for the work since I never got a replacement over the last 3 years. I had to purchase out-of-pocket for use”(Female FGD participants, company B)

“Why worry and go through these procedures at the workplace, when all you get is paperwork and to sit in front of your bosses to narrate your incident over and over again for sympathy and not for assistance now or in the future to avert such an occurrence. So many of our colleagues just take care of themselves with their financial resources if they are injured in the process.”(Male IDI participant, company A)

“Sometimes management does not communicate periodically risk issues and accidents that occur in the workplace to guide our future work efforts for the fear of worker attrition in the company. But that has its negative effects since we are not guided by past happenings to learn from. There is a need for management to change this practice.”(Male FGD participant, company A)

“We don’t have a clinic or even a medical officer employed by the company who takes care of our health or even the daily hazards that we encounter while at work (pointing to a scar on his hand).”(Male FGD participant, company A)

“When you go to the big hospitals where everyone attends for health-seeking, you spend the whole day in wait for care while your work suffers. You can even get back from that health facility and be sanctioned for not coming to work”(Female IDI participant, company B)

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

5.1. Policy Implications

5.2. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lasota, A.M.; Hankiewicz, K. Self-reported fatigue and health complaints of refuse collectors. Cent. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 28, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rogers, J.; Englehardt, J.; An, H.; Fleming, L. Solid waste collection health and safety risks-Survey of municipal solid waste collectors. J. Solid Waste Technol. Manag. 2002, 28, 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Englehardt, J.D.; An, H.; Bean, J.A.; Fleming, L.E.; Dantis, M. Solid Waste Management Health and Safety Risks Epidemiology and Assessment to Support Risk Reduction Report to Florida; Cent Solid Hazard Waste Management University: Miami, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cointreau, S. Occupational and Environmental Health Issues of Solid Waste Management: With Special Emphasis on Middle and Lower-Income Countries I; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gbekor, A. “Domestic waste management”, Ghana Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Newsletter 2003, 47, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Porta, D.; Milani, S.; Lazzarino, A.I.; Perucci, C.A.; Forastiere, F. Systematic review of epidemiological studies on health effects associated with management of solid waste. Environ. Health 2009, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boadi, K.O.; Kuitunen, M. Municipal solid waste management in the Accra Metropolitan Area, Ghana. Environmentalist 2003, 23, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, L. Health hazards and waste management. Br. Med. Bull. 2003, 68, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuijer, P.P.F.M.; Sluiter, J.K.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W. Health and safety in waste collection: Towards evidence-based worker health surveillance. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 1040–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerie, S. Occupational Risks Associated with Solid Waste Management in the Informal Sector of Gweru, Zimbabwe. J. Environ. Public Health 2016, 2016, 9024160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Velasco Garrido, M.; Bittner, C.; Harth, V.; Preisser, A.M. Health status and health-related quality of life of municipal waste collection workers-A cross-sectional survey. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2015, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poulsen, O.M.; Breum, N.O.; Ebbehøj, N.; Hansen, Å.M.; Ivens, U.I.; van Lelieveld, D.; Malmros, P.; Matthiasen, L.; Nielsen, B.H.; Nielsen, E.M.; et al. Collection of domestic waste. Review of occupational health problems and their possible causes. Sci. Total Environ. 1995, 170, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolnikov, T.R.; da Silva, R.C.; Tuesta, A.A.; Marques, C.P.; Cruvinel, V.R.N. Ineffective waste site closures in Brazil: A systematic review on continuing health conditions and occupational hazards of waste collectors. Waste Manag. 2018, 80, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.Y.; Chang, W.T.; Chuang, H.Y.; Tsai, S.S.; Wu, T.N.; Sung, F.C. Adverse health effects among household waste collectors in Taiwan. Environ. Res. 2001, 85, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutberlet, J.; Baeder, A.M. Informal recycling and occupational health in Santo André, Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2008, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyere, R.; Addaney, M.; Ayaribilla Akudugu, J. Decentralization and Solid Waste Management in Urbanizing Ghana: Moving beyond the Status Quo. In Municipal Solid Waste Management; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yeboah-Assiamah, E.; Asamoah, K.; Kyeremeh, T.A. Decades of public-private partnership in solid waste management. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2017, 28, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douti, N.B.; Abanyie, S.K.; Ampofo, S. Solid Waste Management Challenges in Urban Areas of Ghana: A Case Study of Bawku Municipality. Int. J. Geosci. 2017, 8, 494–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fobil, J.; Kolawole, O.; Hogarh, J.; Carboo, D.; Rodrigues, F. Waste Management Financing in Ghana and Nigeria–How Can the Concept of Polluter-Pays-Principle (Ppp) Work in Both Countries? Int. J. Acad. Res. 2010, 2, 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu, G. Social effects of poor sanitation and waste management on poor urban communities: A neighborhood-specific study of Sabon Zongo, Accra. J. Urban. 2010, 3, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, S.T.; Kosoe, E.A. Solid waste management in urban areas of Ghana: Issues and experiences from Wa. J. Environ. Pollut. Hum. Health 2014, 2, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miezah, K.; Obiri-Danso, K.; Kádár, Z.; Fei-Baffoe, B.; Mensah, M.Y. Municipal solid waste characterization and quantification as a measure towards effective waste management in Ghana. Waste Manag. 2015, 46, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anomanyo, E.D. Integration of Municipal Solid Waste Management in Accra (Ghana): Bioreactor Treatment Technology As an Integral Part of the Management Process. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kofoworola, O.F. Recovery and recycling practices in municipal solid waste management in Lagos, Nigeria. Waste Manag. 2007, 27, 1139–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, S.B.; Saphores, J.D.; Feldman, D.L.; Hamilton, A.J.; Fletcher, T.D.; Cook, P.L.M.; Stewardson, M.; Sanders, B.F.; Levin, L.A.; Ambrose, R.F.; et al. Taking the “waste” out of “wastewater” for human water security and ecosystem sustainability. Science 2012, 337, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lin, A.Y.C.; Huang, S.T.Y.; Wahlqvist, M.L. Waste management to improve food safety and security for health advancement. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 18, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boadi, K.O.; Kuitunen, M. Environmental and health impacts of household solid waste handling and disposal practices in Third World cities: The case of the Accra Metropolitan Area, Ghana. J. Environ. Health 2005, 68, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lissah, S.Y.; Ayanore, M.A.; Krugu, J.; Ruiter, R.A.C. Psychosocial risk, work-related stress, and job satisfaction among domestic waste collectors in the Ho municipality of Ghana: A phenomenological study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kanhai, G.; Agyei-Mensah, S.; Mudu, P. Population awareness and attitudes toward waste-related health risks in Accra, Ghana. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2019, 31, 670–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kretchy, J.-P.; Dzodzomenyo, M.; Rheinländer, T.; Ayi, I.; Konradsen, F.; Fobil, J.N.; Dalsgaard, A. Exposure, protection and self-reported health problems among solid waste handlers in a Coastal Peri-urban community in Ghana. Int. J. Public Health Epidemiol. 2015, 4, 2326–7291. [Google Scholar]

- Lissah, S.Y.; Ayanore, M.A.; Krugu, J.K.; Aberese-Ako, M.; Ruiter, R.A.C. Managing urban solid waste in Ghana: Perspectives and experiences of municipal waste company managers and supervisors in an urban municipality. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Asani, P.U.; Zurbrugg, C.; Anapolsky, S.; Mani, S. Improving Municipal Solid Waste Management in India, A Sourcebook for Policy Makers and Practitioners; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- GSS. Projected Population by District and Sex, Volta Region, 2010, 2015–2020; Ghana Statistical Service: Accra, Ghana, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Sekyere, E. Scavenging for wealth or death? Exploring the health risk associated with waste scavenging in kumasi, ghana. Ghana J. Geogr. 2014, 6, 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Elaine Welsh Qualitative Social Research. Forum Qual. Sozialforsch. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2002, 12, 345–357.

- Kottner, J.; Audige, L.; Brorson, S.; Donner, A.; Gajewski, B.J.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Roberts, C.; Shoukri, M.; Streiner, D.L. Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS) were proposed. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberese-Ako, M.; Van Dijk, H.; Gerrits, T.; Arhinful, D.K.; Agyepong, I.A. ‘Your health our concern, our health whose concern?’: Perceptions of injustice in organizational relationships and processes and frontline health worker motivation in Ghana. Health Policy Plan. 2014, 29, ii15–ii28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aberese-Ako, M.; Agyepong, I.A.; Gerrits, T.; Van Dijk, H. I used to fight with them but now I have stopped!: Conflict and doctor-nurse-anaesthetists’ motivation in maternal and neonatal care provision in a specialist referral hospital. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selin, E. Sustainable Municipal Solid Waste Management-A Qualitative Study on Possibilities and Solutions in Mutomo, Kenya; Department of Ecology and Environmental Science (EMG), Umea University: Umea, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Abou-ElWafa, H.S.; El-Bestar, S.F.; El-Gilany, A.H.; Awad, E.E.S. Musculoskeletal disorders among municipal solid waste collectors in Mansoura, Egypt: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2012, 2, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mohammed, S.; Abdul Latif, P.D.P. Possible Health Danger Associated With Gabbage/Refuse Collectors. IOSR J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 2014, 8, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, V.P.; Kamble, R.K. Occupational health hazards in street sweepers of Chandrapur city, central India. Int. J. Environ. 2017, 6, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asumeng, M.; Asamani, L.; Afful, J.; Agyemang, C.B. Occupational Safety and Health Issues in Ghana. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 60–79. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M.; Wilkinson, R.G. (Eds.) Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Ma, M.; Thompson, J.R.; Flower, R.J. Waste management, informal recycling, environmental pollution and public health. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziraba, A.K.; Haregu, T.N.; Mberu, B. A review and framework for understanding the potential impact of poor solid waste management on health in developing countries. Arch. Public Health 2016, 74, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Owusu-sekyere, E.; Osumanu, I.K.; Yaro, J.A. Dompoase Landfill in the Kumasi Metropolitan Area of Ghana: A ‘Blessing’ or a ‘Curse’? Int. J. Curr. Trends Res. 2013, 2, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Oteng-Ababio, M. The role of the informal sector in solid waste management in the Gama, Ghana: Challenges and opportunities. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2011, 103, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.T.; van Nguyen, B.; Do, H.T.T.; Nguyen, B.N.; Nguyen, V.T.; Vu, S.T.; Tran, T.T.T. Psychological stress and associated factors among municipal solid waste collectors in Hanoi, Vietnam: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, J.; Schneider, S.; Von Känel, R. Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom. Med. 2010, 72, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouter, A.C.; Bumpus, M.F.; Head, M.R.; McHale, S.M. Implications of overwork and overload for the quality of men’s family relationships. J. Marriage Fam. 2001, 63, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustaka, Ε.; Constantinidis, T.C. Sources and effects of work-related stress in nursing. Health Sci. J. 2011, 4, 210–216. [Google Scholar]

- Yoada, R.M.; Chirawurah, D.; Adongo, P.B. Domestic waste disposal practice and perceptions of private sector waste management in urban Accra. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gebremedhin, F.; Debere, M.K.; Kumie, A.; Tirfe, Z.M.; Alamdo, A.G. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Among Solid Waste Collectors in Lideta Sub-city on Prevention of Occupational Health Hazards, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Sci. J. Public Health 2016, 4, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Addo, I.B.; Adei, D.; Acheampong, E.O. Solid Waste Management and Its Health Implications on the Dwellers of Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana. Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 7, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, P.; Ganguly, R.; Dhulia, A. Occupational Health Hazard Exposure among municipal solid waste workers in Himachal Pradesh, India. Waste Manag. 2018, 78, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPEC. Addressing the Exploitation of Children in Scavenging (Waste Picking): A Thematic Evaluation of Action on Child Labour. A Thematic Evaluation; International Programme on the Eliminatioo of Child Labour (IPEC), International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, J. WHO Healthy Workplace Framework: Background and Supporting Literature and Practices. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/517787/retrieve (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Leka, S.; Jain, A. Health Impact of Psychosocial Hazards at Work: An Overview; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Alli, B.O. Fundamental principles of occupational health and safety Second edition. Ilo. Int. 2008, 15, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Type of Interview | Participants (DWCs) | Number (n) |

|---|---|---|

| In-Depth Interviews | Company A | 10 |

| Company B | 5 | |

| Total IDIs | 15 | |

| Focus Group Discussions | Company A | 33 |

| Company B | 16 | |

| Total FGDs | 49 |

| 1. Nature of hazards associated with waste collection in the study area Can you indicate the nature of health hazards associated with your work? Probe further if the participant names any of the following.

|

| 2. Factors that can expose domestic waste collectors to occupational hazards Indicate the factors which in your view can expose you to the risk and occupational and health hazards in your workplace. Probe further if the participant names any of the following.

|

|

3. Preventive measures for safety and health hazards at the workplace Do you know how/what health and safety measures are required in your workplace? Probe further if the participant names any of the following.

|

| Characteristics | Company A | Company B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manager/Supervisor | DWC | Manager/Supervisor | DWC | |

| Age in Years | n | n | n | n |

| 21–30 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 31–40 | 12 | 10 | 4 | 5 |

| 41–50 | 6 | 17 | 2 | 10 |

| 51–60 | 4 | 11 | 2 | 4 |

| 61+ | - | 3 | - | 1 |

| Ethnic Group of Participants | ||||

| Ewe | 22 | 42 | 10 | 19 |

| Other | 3 | 1 | - | 2 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Married | 22 | 27 | 7 | 13 |

| Divorced/separated | - | 3 | - | 1 |

| Widow/widower | - | 8 | - | 4 |

| Religion | ||||

| Christian | 18 | 27 | 8 | 14 |

| Muslim | 2 | 3 | - | 1 |

| Traditionalist | 2 | 11 | 1 | 5 |

| No religion | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Educational Level | ||||

| MSLC | - | 11 | - | 5 |

| JSS | - | 9 | - | 5 |

| Vocational training | - | 3 | - | 2 |

| None | - | 20 | - | 9 |

| SHS | 15 | - | 8 | - |

| Tertiary | 10 | - | 2 | - |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 4 | 29 | 2 | 13 |

| Male | 21 | 14 | 8 | 8 |

| Number of Years in the Workplace | ||||

| Below 1 year | - | - | - | - |

| 1–5 years | 6 | 8 | 3 | 8 |

| 6–10 years | 17 | 23 | - | 13 |

| 11–15 years | 2 | 7 | - | - |

| 16–20 years | - | 5 | - | - |

| 21 and above | - | - | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lissah, S.Y.; Ayanore, M.A.; Krugu, J.K.; Aberese-Ako, M.; Ruiter, R.A.C. “Our Work, Our Health, No One’s Concern”: Domestic Waste Collectors’ Perceptions of Occupational Safety and Self-Reported Health Issues in an Urban Town in Ghana. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116539

Lissah SY, Ayanore MA, Krugu JK, Aberese-Ako M, Ruiter RAC. “Our Work, Our Health, No One’s Concern”: Domestic Waste Collectors’ Perceptions of Occupational Safety and Self-Reported Health Issues in an Urban Town in Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116539

Chicago/Turabian StyleLissah, Samuel Yaw, Martin Amogre Ayanore, John K. Krugu, Matilda Aberese-Ako, and Robert A. C. Ruiter. 2022. "“Our Work, Our Health, No One’s Concern”: Domestic Waste Collectors’ Perceptions of Occupational Safety and Self-Reported Health Issues in an Urban Town in Ghana" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 11: 6539. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116539