Behavioral, Histopathological, and Biochemical Implications of Aloe Emodin in Copper-Aβ-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease-like Model Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Animals

2.3. Preparation of the Solutions

2.4. The Construction of Animal Models

2.5. Animal Administration

2.6. Behavioral Tests

2.6.1. Y-Maze Test (YMT)

2.6.2. Open Field Test (OFT)

2.6.3. Morris Water Maze Test (MWM)

2.7. Sample Preparation

2.8. Histopathology Assessment

2.8.1. Nissl Staining

2.8.2. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

2.9. Measurement of Copper Content

2.9.1. Serum Copper Content

2.9.2. Brain Copper Content

2.10. Western Blot

2.11. Biochemical Assays

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

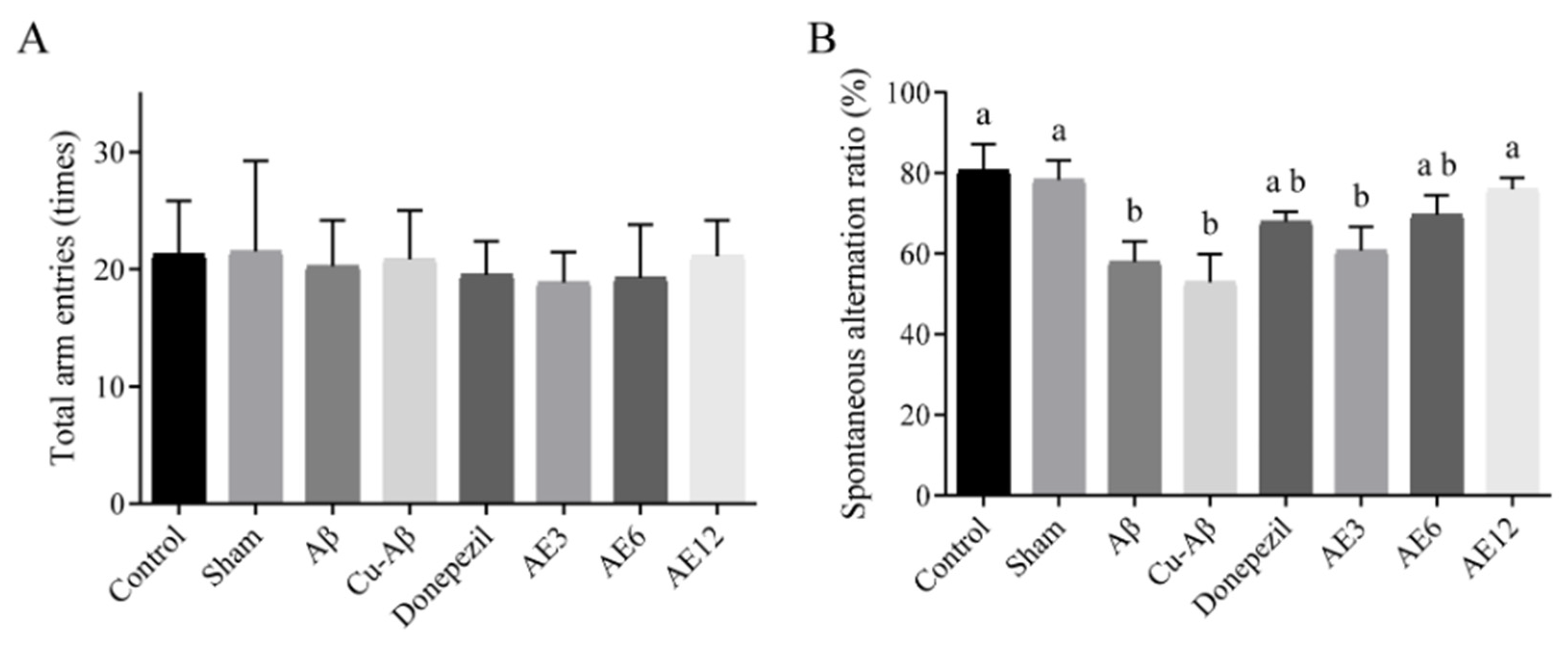

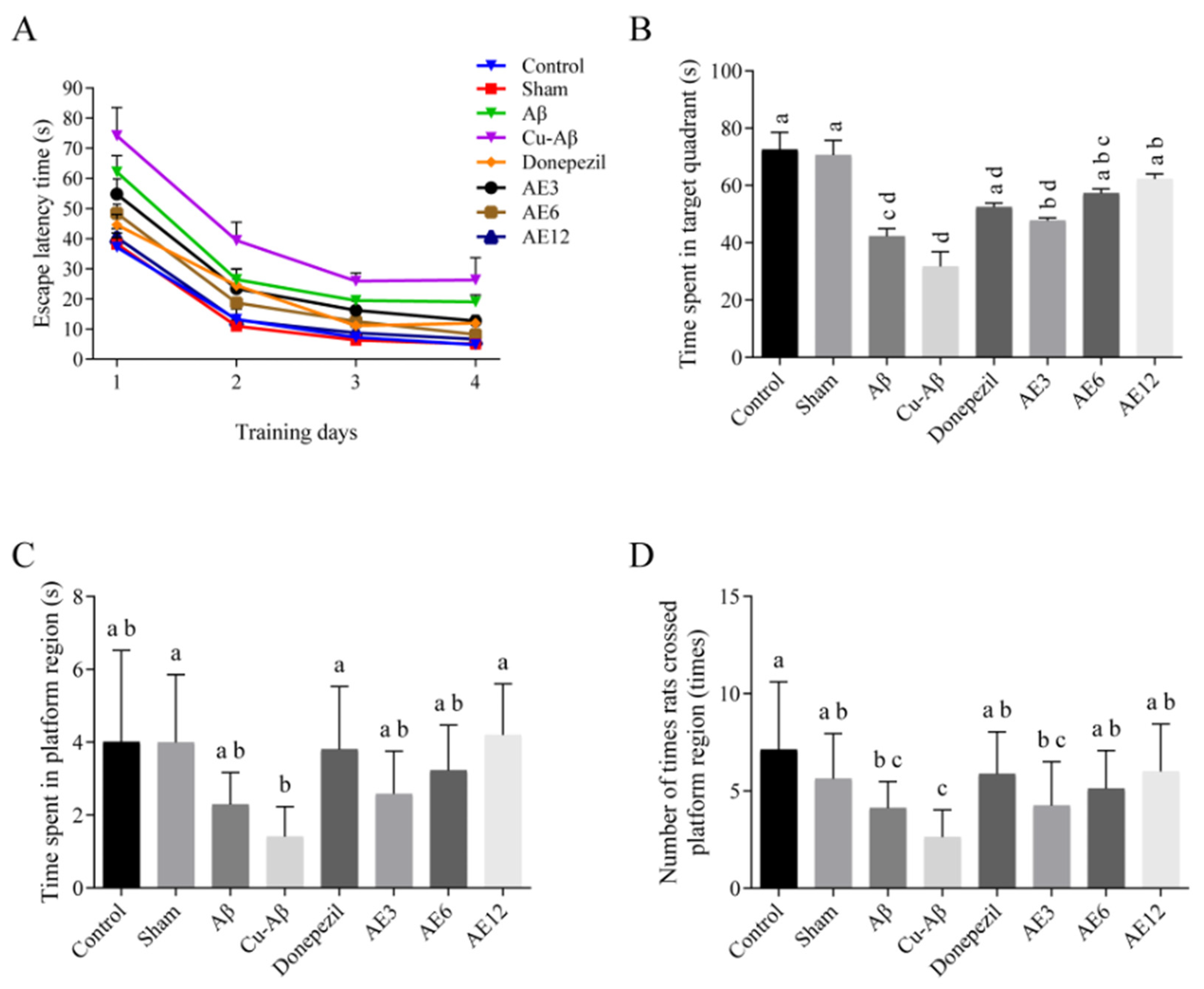

3.1. AE Inhibits the Cognitive Impairment of AD-like Model Rats

3.1.1. Y-Maze Test

3.1.2. Open Field Test

3.1.3. Morris Water Maze Test

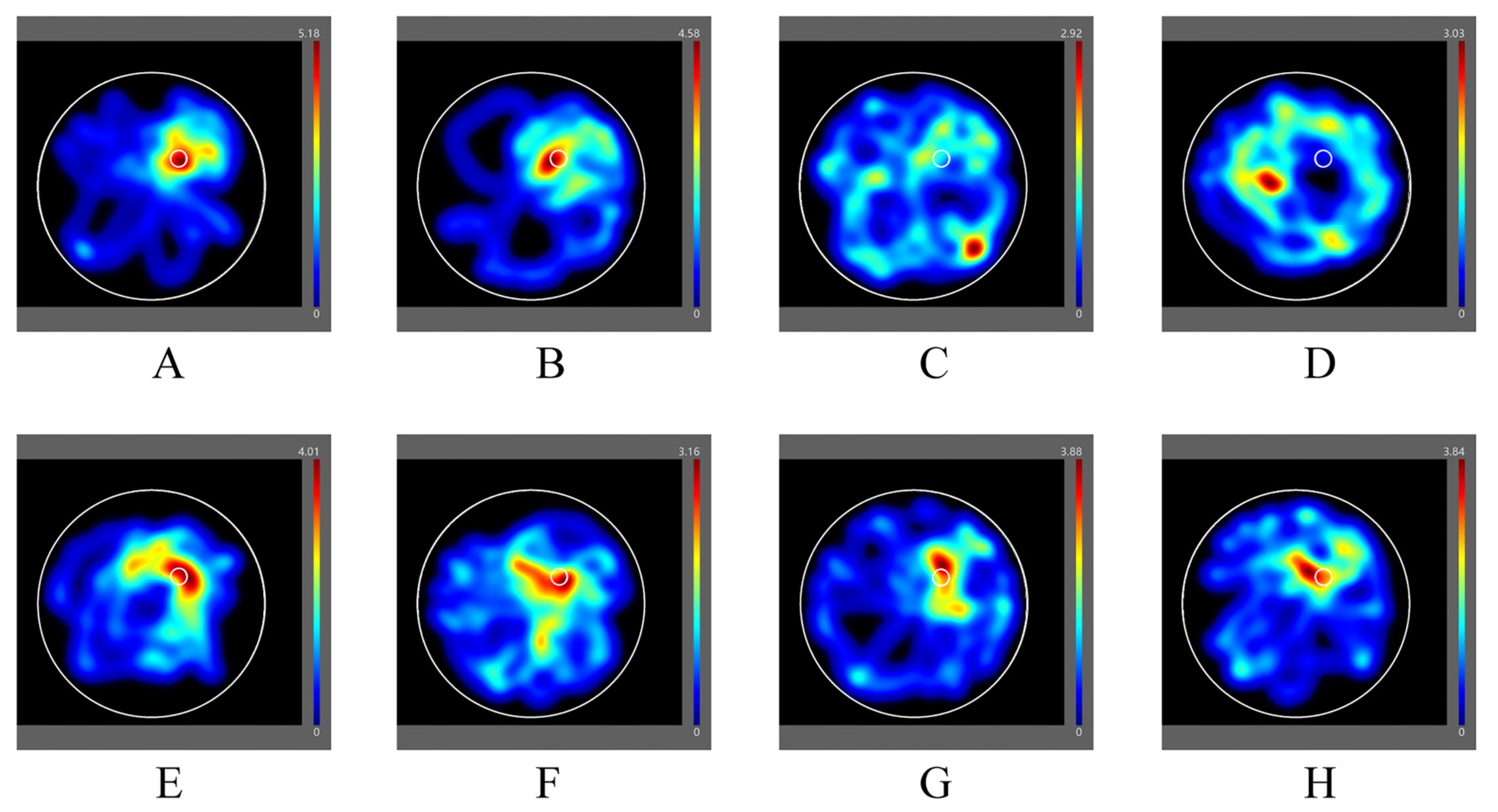

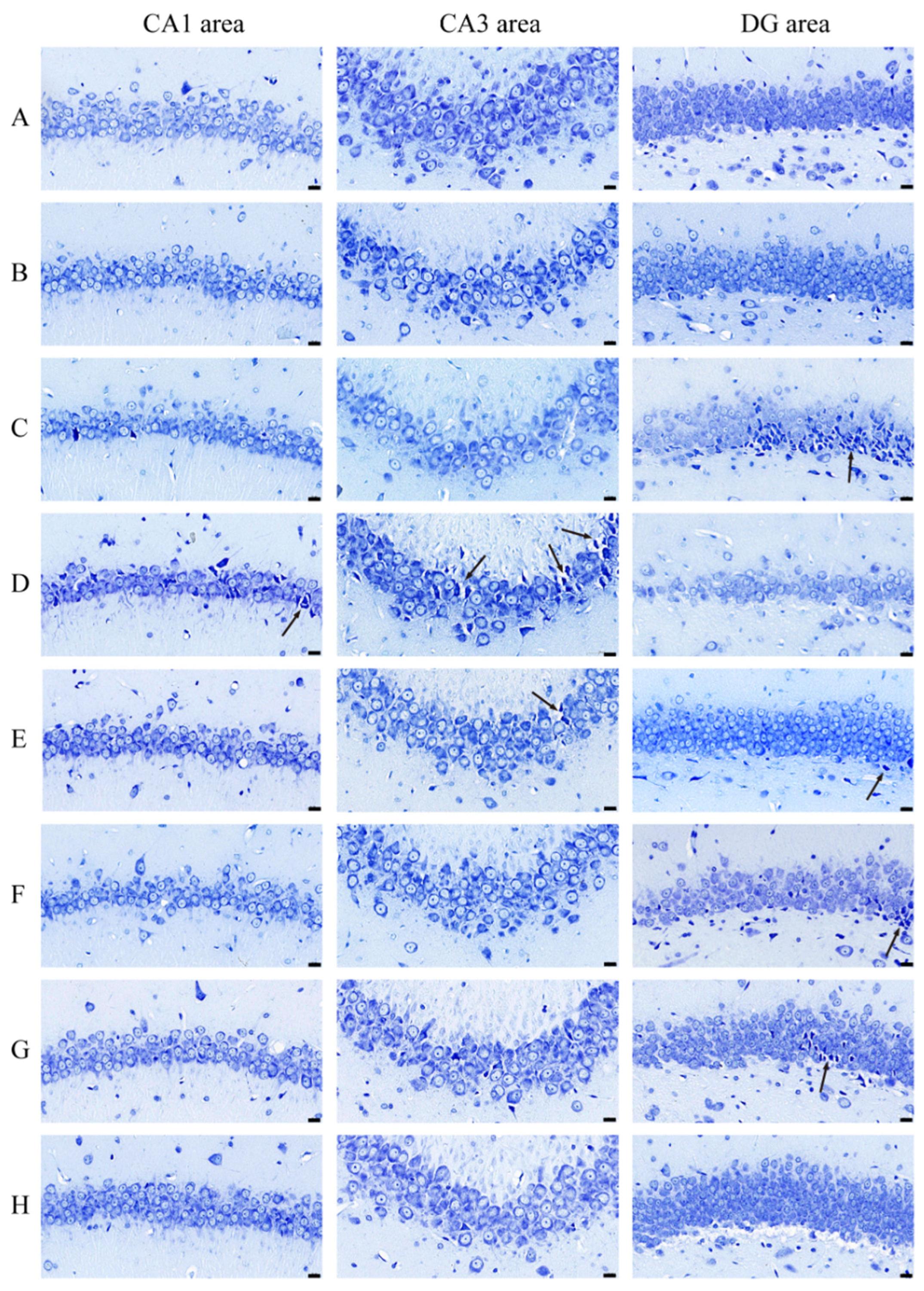

3.2. AE Ameliorates Neuronal Apoptosis in Hippocampus of AD-like Model Rats

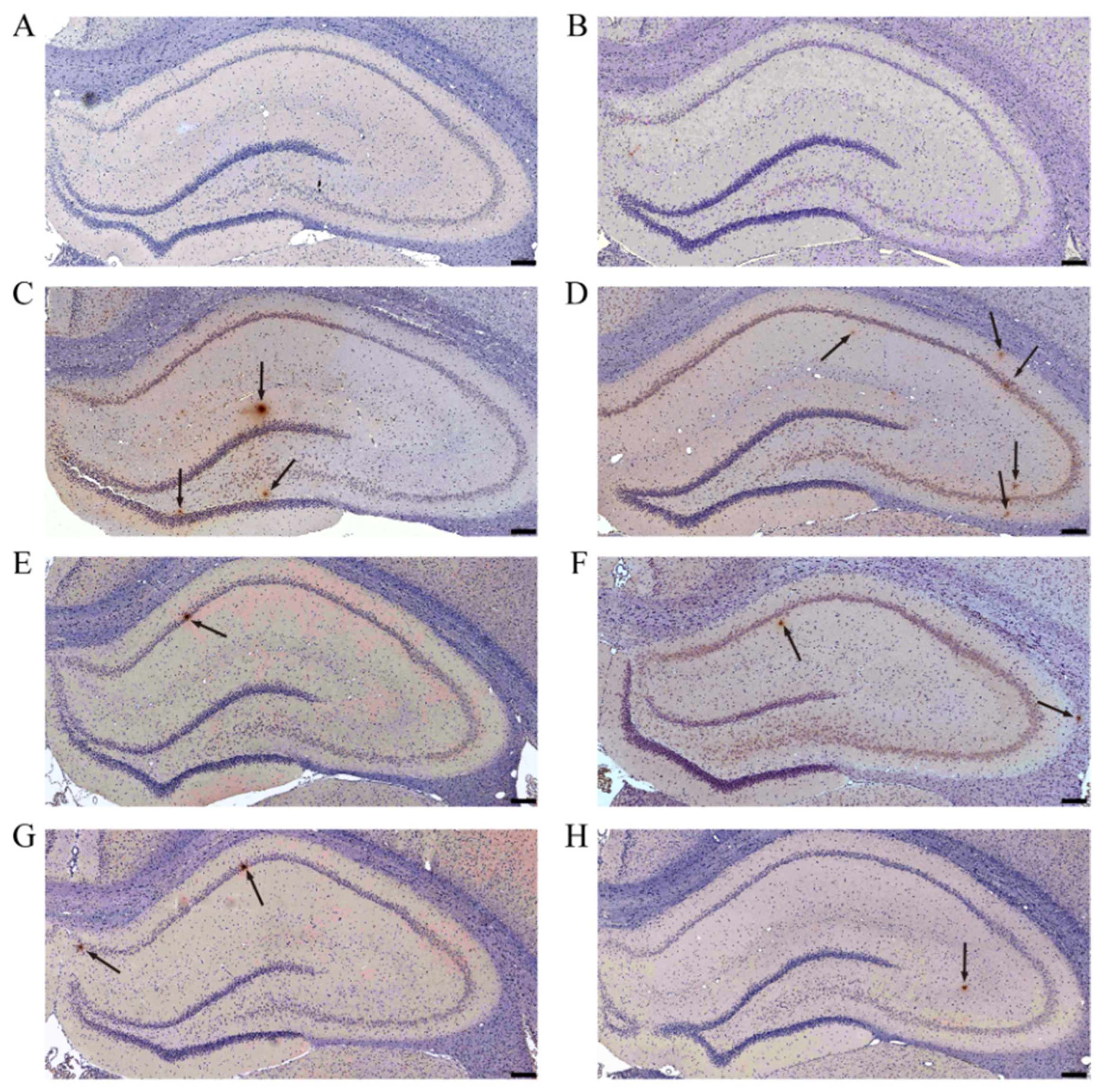

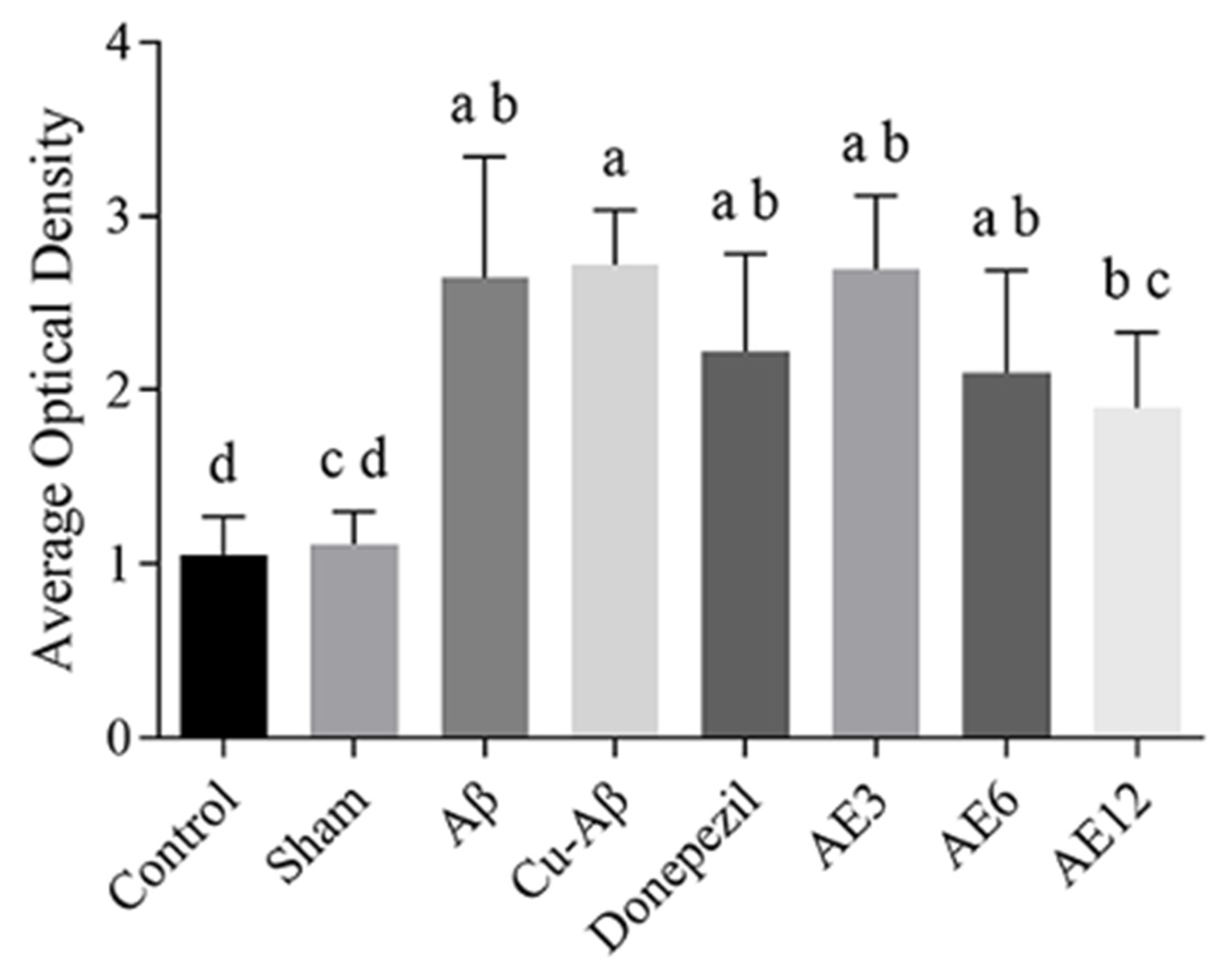

3.3. AE Reduces the Deposition of Aβ in Hippocampus of AD-like Model Rats

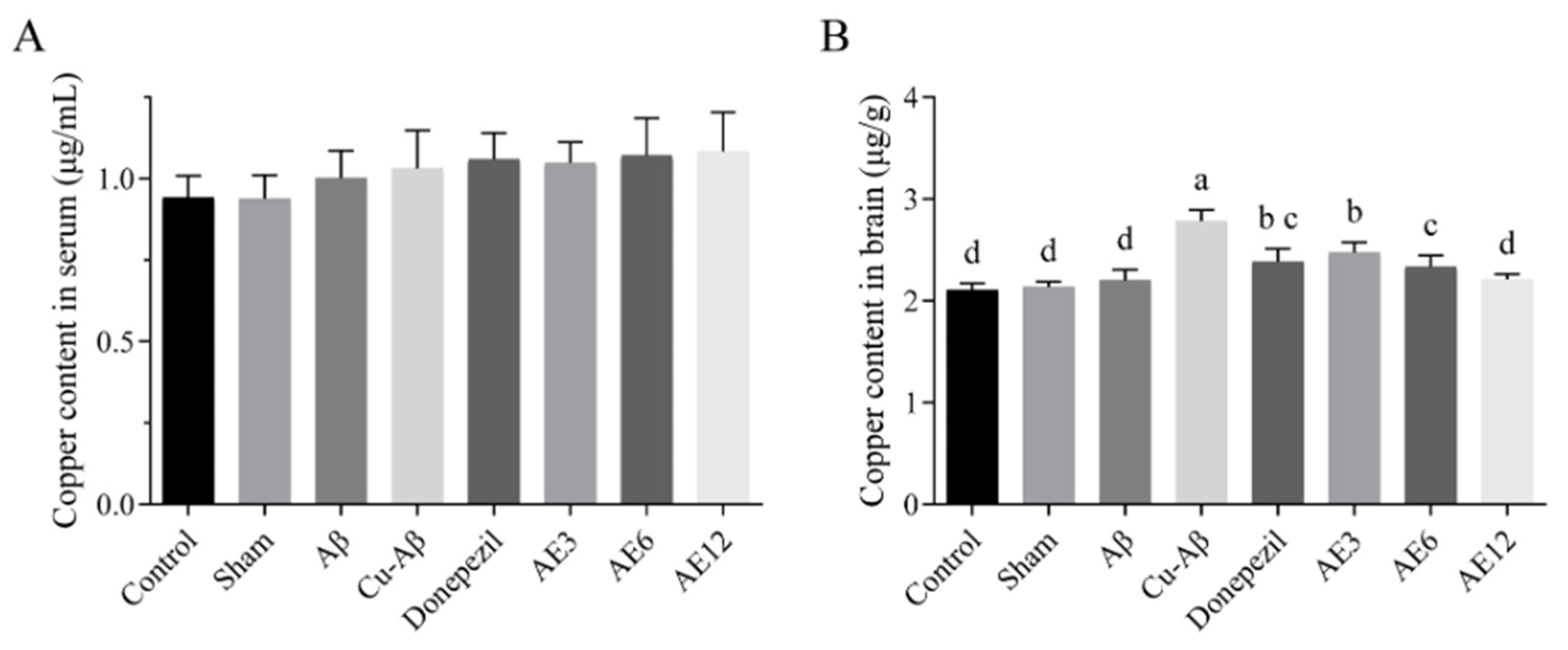

3.4. AE Decreased Copper Levels in Brain of AD-like Model Rats

3.4.1. Method Validation

3.4.2. Quantitative ICP-MS Measurements

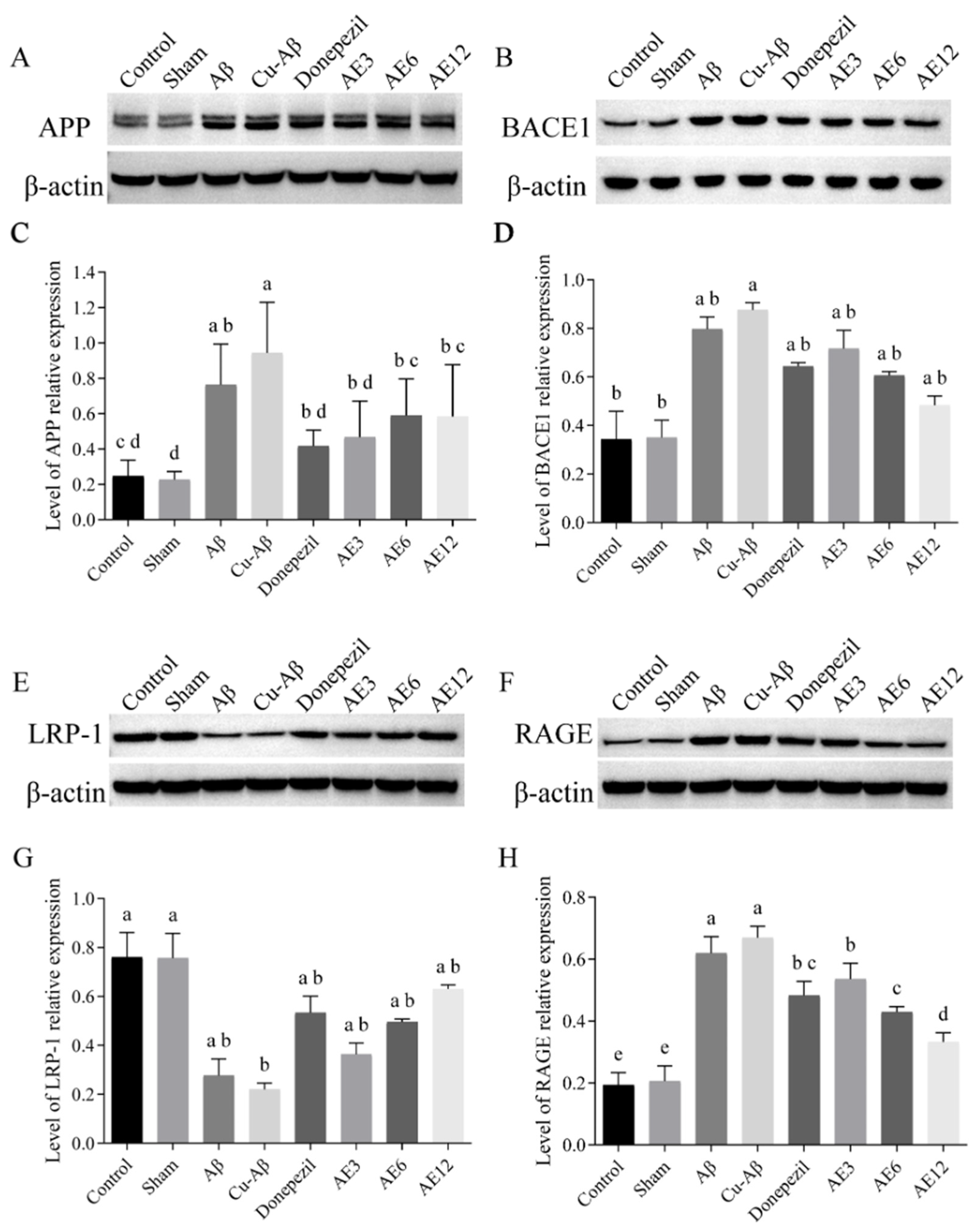

3.5. AE Influenced the Expression of Protein Associated with Aβ Production and Transporter

3.5.1. Protein Associated with Aβ Production

3.5.2. Protein Associated with Aβ Transporter

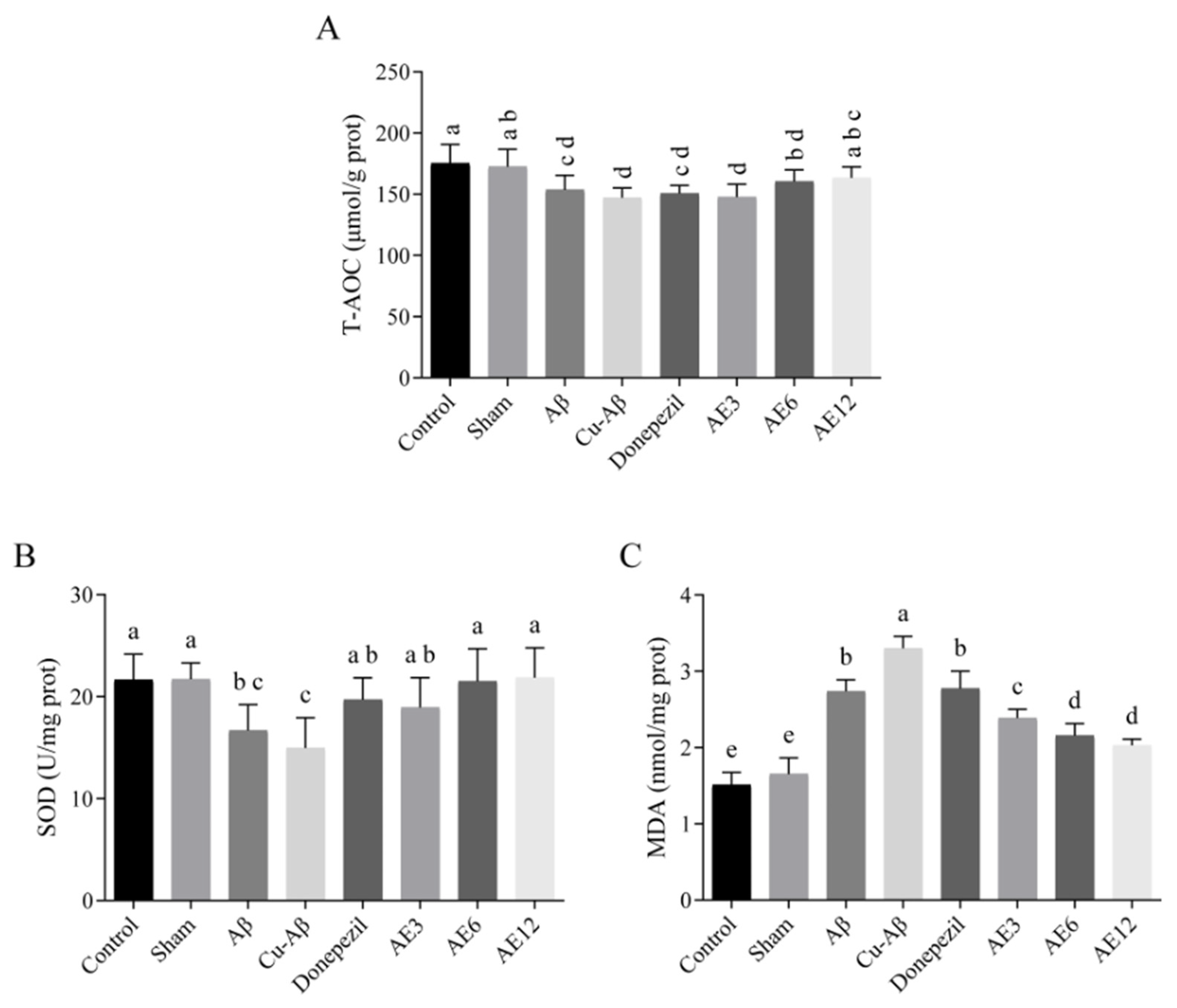

3.6. AE Improved the Antioxidant Capacity of AD-like Model Rats

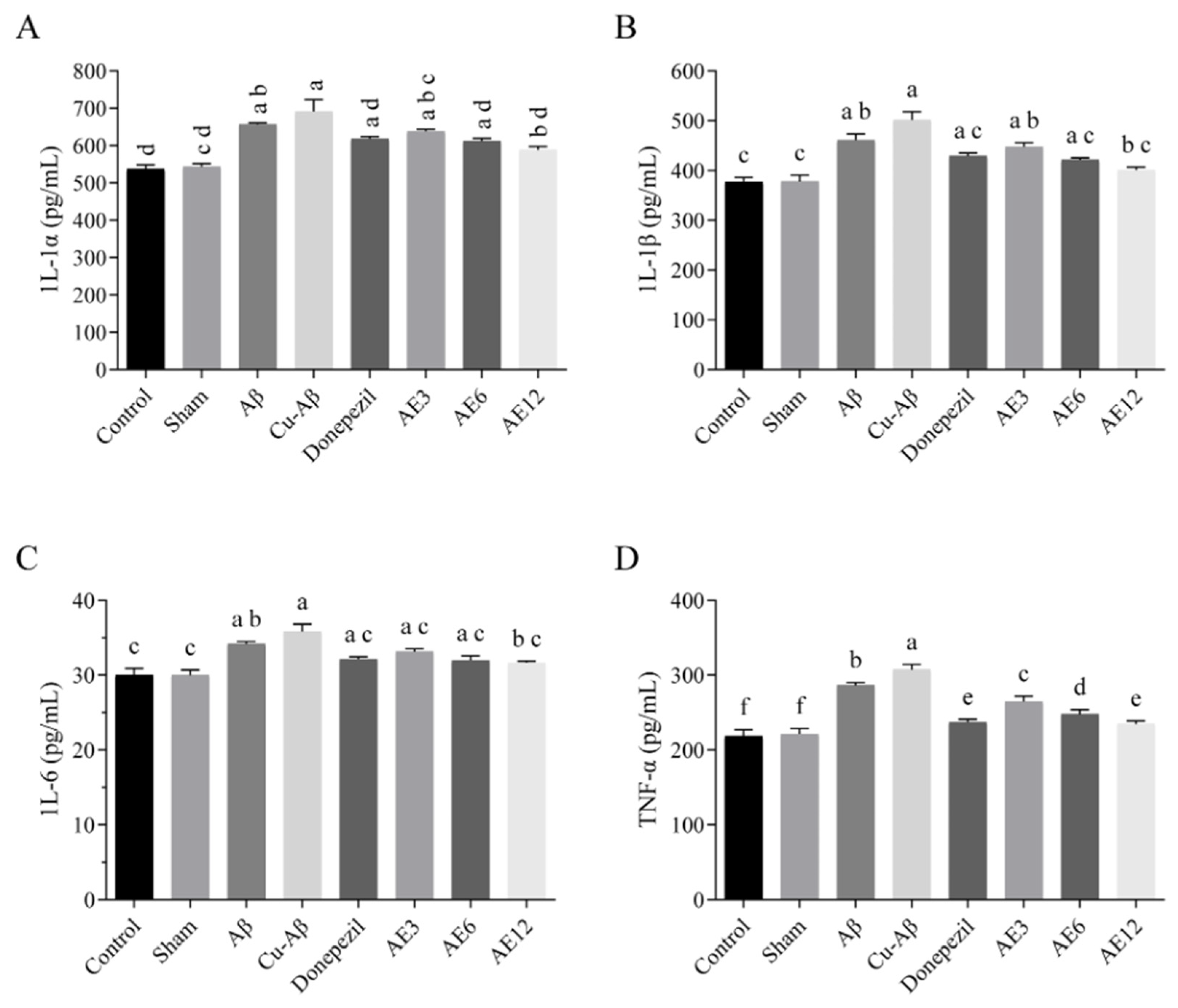

3.7. AE Alleviated the Neuroinflammation in the Brain of AD-like Model Rats

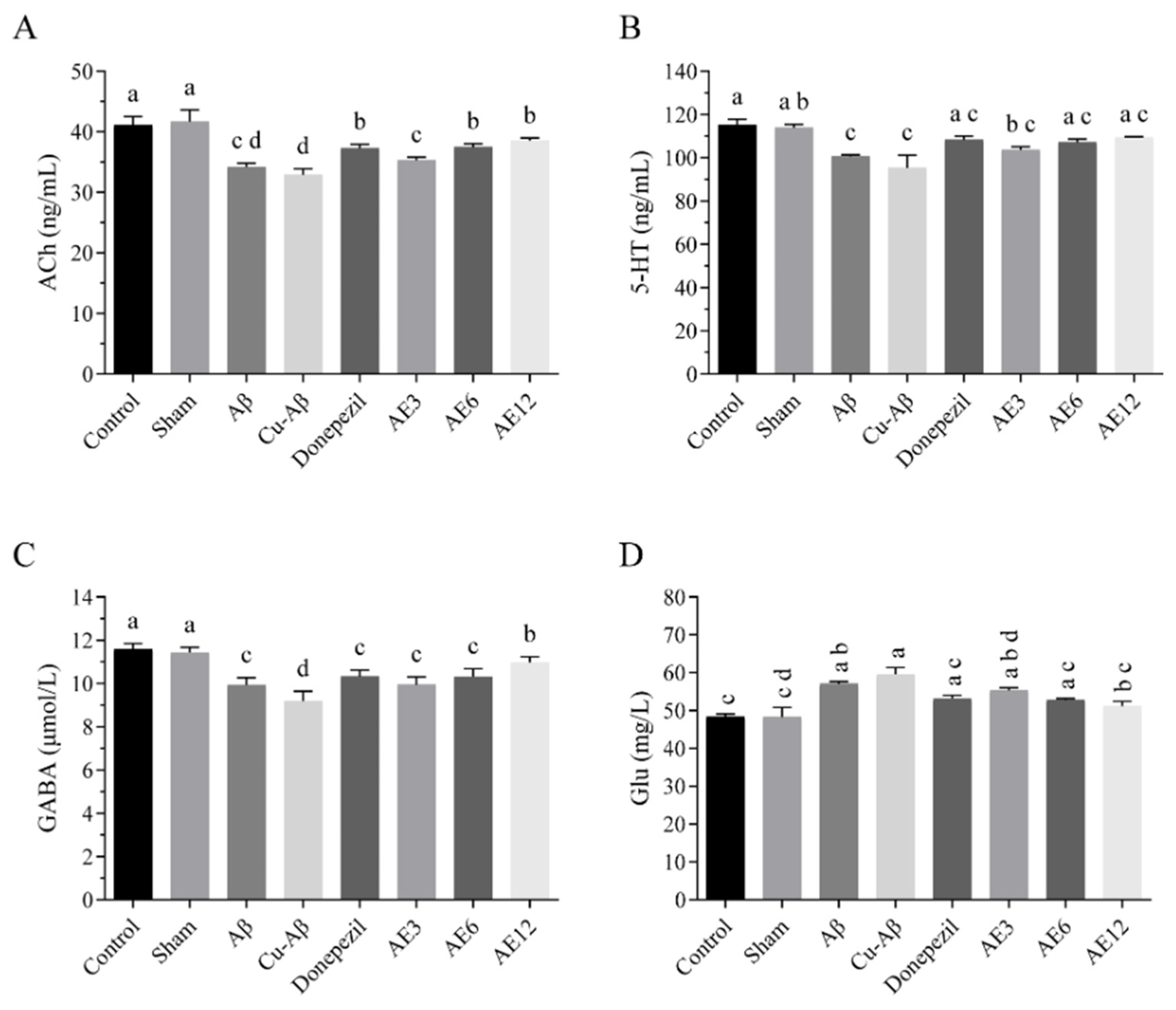

3.8. AE Regulated the Neurotransmitter Dyshomeostasis in the Brain of AD-like Model Rats

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2024 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 3708–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, K.; Ranasinghe, K.G.; Morise, H.; Syed, F.; Sekihara, K.; Rankin, K.P.; Miller, B.L.; Kramer, J.H.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Vossel, K.; et al. Neurophysiological Trajectories in Alzheimer’s Disease Progression. eLife 2024, 12, RP91044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, L. An Age-Old Story of Dementia. Nature 2018, 559, S2–S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.; Allsop, D. Amyloid Deposition as the Central Event in the Aetiology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1991, 12, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasb, M.; Tao, W.; Chen, N. Alzheimer’s Disease Puzzle: Delving into Pathogenesis Hypotheses. Aging Dis. 2024, 15, 43–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Selkoe, D.J.; Hardy, J. The Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease at 25 Years. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtain, C.C.; Ali, F.E.; Smith, D.G.; Bush, A.I.; Masters, C.L.; Barnham, K.J. Metal Ions, pH, and Cholesterol Regulate the Interactions of Alzheimer’s Disease Amyloid-Beta Peptide with Membrane Lipid. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 2977–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sensi, S.L.; Granzotto, A.; Siotto, M.; Squitti, R. Copper and Zinc Dysregulation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 39, 1049–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, A.; Liu, Y.; Nguyen, M.; Meunier, B. Regulation of Copper and Iron Homeostasis by Metal Chelators: A Possible Chemotherapy for Alzheimer’s Disease. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1332–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, I.; Sagare, A.P.; Coma, M.; Perlmutter, D.; Gelein, R.; Bell, R.D.; Deane, R.J.; Zhong, E.; Parisi, M.; Ciszewski, J.; et al. Low Levels of Copper Disrupt Brain Amyloid-β Homeostasis by Altering Its Production and Clearance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 14771–14776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Shang, Q.; Liang, R.; Viles, J.H. Copper(II) Can Kinetically Trap Arctic and Italian Amyloid-Β40 as Toxic Oligomers, Mimicking Cu(II) Binding to Wild-Type Amyloid-Β42: Implications for Familial Alzheimer’s Disease. JACS Au 2024, 4, 578–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kepp, K.P. Alzheimer’s Disease: How Metal Ions Define β-Amyloid Function. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 351, 127–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, S.; Yatin, S.; Aksenova, M.; Butterfield, D.A. Review: Alzheimer’s Amyloid Beta-Peptide-Associated Free Radical Oxidative Stress and Neurotoxicity. J. Struct. Biol. 2000, 130, 184–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheignon, C.; Tomas, M.; Bonnefont-Rousselot, D.; Faller, P.; Hureau, C.; Collin, F. Oxidative Stress and the Amyloid Beta Peptide in Alzheimer’s Disease. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faller, P.; Hureau, C.; Berthoumieu, O. Role of Metal Ions in the Self-Assembly of the Alzheimer’s Amyloid-β Peptide. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 12193–12206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattatray Shinde, S.; Kumar Behera, S.; Kulkarni, N.; Dewangan, B.; Sahu, B. Bifunctional Backbone Modified Squaramide Dipeptides as Amyloid Beta (Aβ) Aggregation Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2024, 97, 117538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puentes-Díaz, N.; Chaparro, D.; Morales-Morales, D.; Alí-Torres, J.; Flores-Gaspar, A. Pincer Ligands as Multifunctional Agents for Alzheimer’s Copper Dysregulation and Oxidative Stress: A Computational Evaluation. ChemPlusChem 2023, 88, e202300405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.-L.; Guo, C.; Hou, J.-Q.; Feng, J.-H.; Zhang, Z.; Xiong, F.; Ye, W.-C.; Wang, H. Stereoisomers of Schisandrin B Are Potent ATP Competitive GSK-3β Inhibitors with Neuroprotective Effects against Alzheimer’s Disease: Stereochemistry and Biological Activity. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 996–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Zhao, H.; Yin, Z.; Han, C.; Wang, Y.; Luo, G.; Gao, X. Rheum Tanguticum Alleviates Cognitive Impairment in APP/PS1 Mice by Regulating Drug-Responsive Bacteria and Their Corresponding Microbial Metabolites. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 766120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, Y.; You, L.; Yin, X.; Fu, J.; Ni, J. Aloe-Emodin: A Review of Its Pharmacology, Toxicity, and Pharmacokinetics. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, G.-C.; Duh, P.-D.; Chuang, D.-Y. Antioxidant Activity of Anthraquinones and Anthrone. Food Chem. 2000, 70, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, R.; Zhao, W.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, A.; Kou, X. Emodin Derivatives as Promising Multi-Aspect Intervention Agents for Amyloid Aggregation: Molecular Docking/Dynamics Simulation, Bioactivities Evaluation, and Cytoprotection. Mol. Divers. 2023, 28, 3085–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-L.; Poon, C.-Y.; Lin, C.; Yan, T.; Kwong, D.W.-J.; Yung, K.K.-L.; Wong, M.S.; Bian, Z.; Li, H.-W. Inhibition of β-Amyloid Aggregation By Albiflorin, Aloeemodin And Neohesperidin And Their Neuroprotective Effect On Primary Hippocampal Cells Against β-Amyloid Induced Toxicity. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2015, 12, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convertino, M.; Pellarin, R.; Catto, M.; Carotti, A.; Caflisch, A. 9,10-Anthraquinone Hinders Beta-Aggregation: How Does a Small Molecule Interfere with Abeta-Peptide Amyloid Fibrillation? Protein Sci. 2009, 18, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, M.; Cai, J.; Zheng, K.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Lin, H.; Liang, S.; Wang, S. Aloe-Emodin Prevents Nerve Injury and Neuroinflammation Caused by Ischemic Stroke via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and NF-κB Pathway. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 8056–8067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, M.; Govindaraju, T. Multipronged Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategies for Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 13657–13689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chromy, B.A.; Nowak, R.J.; Lambert, M.P.; Viola, K.L.; Chang, L.; Velasco, P.T.; Jones, B.W.; Fernandez, S.J.; Lacor, P.N.; Horowitz, P.; et al. Self-Assembly of Abeta(1-42) into Globular Neurotoxins. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 12749–12760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Choi, J.W.; Ree, J.; Lim, J.S.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.I.; Thapa, S.B.; Sohng, J.K.; Park, Y.I. Aloe Emodin 3-O-Glucoside Inhibits Cell Growth and Migration and Induces Apoptosis of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Cells via Suppressing MEK/ERK and Akt Signalling Pathways. Life Sci. 2022, 300, 120495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fronza, M.G.; Baldinotti, R.; Sacramento, M.; Gutierres, J.; Carvalho, F.B.; Fernandes, M.d.C.; Sousa, F.S.S.; Seixas, F.K.; Collares, T.; Alves, D.; et al. Effect of QTC-4-MeOBnE Treatment on Memory, Neurodegeneration, and Neurogenesis in a Streptozotocin-Induced Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Qiu, H.-M.; Fei, H.-Z.; Hu, X.-Y.; Xia, H.-J.; Wang, L.-J.; Qin, L.-J.; Jiang, X.-H.; Zhou, Q.-X. Histone Acetylation and Expression of Mono-Aminergic Transmitters Synthetases Involved in CUS-Induced Depressive Rats. Exp. Biol. Med. 2014, 239, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, A.; Badyal, R.K.; Vasishta, R.K.; Attri, S.V.; Thapa, B.R.; Prasad, R. Biochemical, Histological, and Memory Impairment Effects of Chronic Copper Toxicity: A Model for Non-Wilsonian Brain Copper Toxicosis in Wistar Rat. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2013, 153, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Gaber, S.A.; Hamza, A.H.; Tantawy, M.A.; Toraih, E.A.; Ahmed, H.H. Germanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Mitigate Biochemical and Molecular Changes Characterizing Alzheimer’s Disease in Rats. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Z.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Shang, H. Electroacupuncture Enhances Neuroplasticity by Regulating the Orexin A-Mediated cAMP/PKA/CREB Signaling Pathway in Senescence-Accelerated Mouse Prone 8 (SAMP8) Mice. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 8694462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi-Gahrouei, D.; Abdolahi, M. The Correlation between High Background Radiation and Blood Level of the Trace Elements (Copper, Zinc, Iron and Magnesium) in Workers of Mahallat′s Hot Springs. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2012, 1, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairuz, T.; Heo, J.-C.; Lee, J.-H. Differential Glial Response and Neurodegenerative Patterns in CA1, CA3, and DG Hippocampal Regions of 5XFAD Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkadhi, K.A. Cellular and Molecular Differences Between Area CA1 and the Dentate Gyrus of the Hippocampus. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 6566–6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadleir, K.R.; Kandalepas, P.C.; Buggia-Prévot, V.; Nicholson, D.A.; Thinakaran, G.; Vassar, R. Presynaptic Dystrophic Neurites Surrounding Amyloid Plaques Are Sites of Microtubule Disruption, BACE1 Elevation, and Increased Aβ Generation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 132, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassar, R.; Bennett, B.D.; Babu-Khan, S.; Kahn, S.; Mendiaz, E.A.; Denis, P.; Teplow, D.B.; Ross, S.; Amarante, P.; Loeloff, R.; et al. Beta-Secretase Cleavage of Alzheimer’s Amyloid Precursor Protein by the Transmembrane Aspartic Protease BACE. Science 1999, 286, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, Q.; Yu, X.; Liang, Y. Rhubarb Anthraquinone Glycosides Protect against Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rats by Regulating Brain-Gut Neurotransmitters. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2021, 35, e5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, J.V.; Arne, S.; Alexei, V. Astrocyte Energy and Neurotransmitter Metabolism in Alzheimer’s Disease: Integration of the Glutamate/GABA-Glutamine Cycle. Prog. Neurobiol. 2022, 217, 102331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, R.; Mathew, B.J.; Chourasia, R.; Singh, A.K.; Chaurasiya, S.K. Glutamate Decarboxylase Confers Acid Tolerance and Enhances Survival of Mycobacteria within Macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wu, S.; Wang, Q.; Ding, H. Protective Effects of Aloe-Emodin on Scopolamine-Induced Memory Impairment in Mice and H2O2-Induced Cytotoxicity in PC12 Cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 5385–5389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Atwood, C.S.; Anderson, V.E.; Siedlak, S.L.; Smith, M.A.; Perry, G.; Carey, P.R. Metal Binding and Oxidation of Amyloid-Beta within Isolated Senile Plaque Cores: Raman Microscopic Evidence. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 2768–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Shi, Q.; Tian, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Robert, A.; Liu, Q.; Meunier, B. TDMQ20, a Specific Copper Chelator, Reduces Memory Impairments in Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Models. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Prasad, R. An Overview of Various Mammalian Models to Study Chronic Copper Intoxication Associated Alzheimer’s Disease like Pathology. Biometals 2015, 28, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scolari Grotto, F.; Glaser, V. Are High Copper Levels Related to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Articles Published between 2011 and 2022. Biometals 2024, 37, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Wang, B.; Cui, Y.; Tian, S.; Zhang, Y.; You, L.; Chang, Y.-Z.; Gao, G. Hepcidin Deficiency Impairs Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Mediates Brain Atrophy and Memory Decline in Mice. J. Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Balendra, V.; Obaid, A.A.; Esposto, J.; Tikhonova, M.A.; Gautam, N.K.; Poeggeler, B. Copper-Mediated β-Amyloid Toxicity and Its Chelation Therapy in Alzheimer’s Disease. Metallomics 2022, 14, mfac018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, E.; Nobili, G.; Okafor, M.; Proux, O.; Rossi, G.; Morante, S.; Faller, P.; Stellato, F. Chasing the Elusive “In-Between” State of the Copper-Amyloid β Complex by X-ray Absorption through Partial Thermal Relaxation after Photoreduction. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202217791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourrout, M.; Roux, M.; Boisvert, C.; Gislard, C.; Legland, D.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Olivier, C.; Peyrin, F.; Boutin, H.; Rama, N.; et al. Brain Virtual Histology with X-Ray Phase-Contrast Tomography Part II: 3D Morphologies of Amyloid-β Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease Models. Biomed. Opt. Express 2022, 13, 1640–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiethoff, H.; Mohr, I.; Fichtner, A.; Merle, U.; Schirmacher, P.; Weiss, K.H.; Longerich, T. Metallothionein: A Game Changer in Histopathological Diagnosis of Wilson Disease. Histopathology 2023, 83, 936–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Ji, X.; Zhang, M.; Ren, Y.; Tan, R.; Jiang, H.; Wu, X. Aloe-Emodin: Progress in Pharmacological Activity, Safety, and Pharmaceutical Formulation Applications. Mini. Rev. Med. Chem. 2024, 24, 1784–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlack, K.; Tardiff, D.; Narayan, P.; Hamamichi, S.; Caldwell, K.; Caldwell, G.; Lindquist, S. Clioquinol Promotes the Degradation of Metal-Dependent Amyloid-β (Aβ) Oligomers to Restore Endocytosis and Ameliorate Aβ Toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4013–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekhar, K.; Mehta, K.; Govindaraju, T. Hybrid Multifunctional Modulators Inhibit Multifaceted Aβ Toxicity and Prevent Mitochondrial Damage. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 1432–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charissopoulos, E.; Pontiki, E. Targeting Metal Imbalance and Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer’s Disease with Novel Multifunctional Compounds. Molecules 2025, 30, 3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanta, S.; Rajasekhar, K.; Babagond, V.; Govindaraju, T. Small Molecule Inhibits Metal-Dependent and -Independent Multifaceted Toxicity of Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 3611–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, S.; Suseela, Y.V.; Samanta, S.; Vileno, B.; Faller, P.; Govindaraju, T. Fluorescent Peptides Sequester Redox Copper to Mitigate Oxidative Stress, Amyloid Toxicity, and Neuroinflammation. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasekhar, K.; Madhu, C.; Govindaraju, T. Natural Tripeptide-Based Inhibitor of Multifaceted Amyloid β Toxicity. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 1300–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon-Jones, E.E.; Pope, S.J.A. The Coordination Chemistry of Substituted Anthraquinones: Developments and Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 269, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Xi, J.; Fang, J.; Zhang, B.; Cai, W. Aloe-Emodin Alleviates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity via Inhibition of Ferroptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 206, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Pan, X.; Li, X.; Wu, B. Study on the antioxidant activity of Aloe-emodin metal complex. J. Sichuan Univ. (Med. Sci.) 2021, 52, 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, Y.; Du, B.; Fan, W.; Wang, C.; Yin, J.; Fang, F.; Guan, J. Effect of Aloe Emodin on the Aggregation and Cytotoxicity of Aβ42 in the Presence of Cu2+. Cent. South Pharm. 2024, 22, 3133–3138. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Yao, N.; Fan, W.; Du, B.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; Song, L.; Yin, J.; Fang, F.; Guan, J. Ameliorating Effects of Aloe Emodin in an Aluminum-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease Rat Model. J. Food Biochem. 2024, 2024, 7306081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups | Number of Entries in the Center Zone (Times) | Duration in the Center Zone (s) |

|---|---|---|

| control group | 7.75 ± 2.60 a | 28.56 ± 9.71 a |

| sham group | 7.38 ± 2.07 ab | 23.78 ± 5.38 a |

| hippo-Aβ group | 2.25 ± 1.28 d | 5.69 ± 1.58 c |

| hippo-CuAβ group | 2.13 ± 1.13 d | 3.36 ± 1.88 c |

| donepezil group | 5.25 ± 1.98 c | 12.95 ± 4.38 ac |

| low-dose AE group | 3.00 ± 1.85 d | 6.87 ± 1.66 bc |

| medium-dose AE group | 5.63 ± 2.00 bc | 12.54 ± 2.38 ac |

| high-dose AE group | 7.75 ± 2.32 a | 17.81 ± 3.59 ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, X.; Yin, J.; Du, B.; Fan, W.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Fang, F.; Guan, J. Behavioral, Histopathological, and Biochemical Implications of Aloe Emodin in Copper-Aβ-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease-like Model Rats. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010086

Zhao X, Yin J, Du B, Fan W, Chen Y, Yang Y, Fang F, Guan J. Behavioral, Histopathological, and Biochemical Implications of Aloe Emodin in Copper-Aβ-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease-like Model Rats. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010086

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Xitong, Jianing Yin, Baojian Du, Wenqian Fan, Yang Chen, Yazhu Yang, Fang Fang, and Jun Guan. 2026. "Behavioral, Histopathological, and Biochemical Implications of Aloe Emodin in Copper-Aβ-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease-like Model Rats" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010086

APA StyleZhao, X., Yin, J., Du, B., Fan, W., Chen, Y., Yang, Y., Fang, F., & Guan, J. (2026). Behavioral, Histopathological, and Biochemical Implications of Aloe Emodin in Copper-Aβ-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease-like Model Rats. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010086