Inhibition of Inflammation by an Air-Based No-Ozone Cold Plasma in TNF-α-Induced Human Keratinocytes: An In Vitro Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

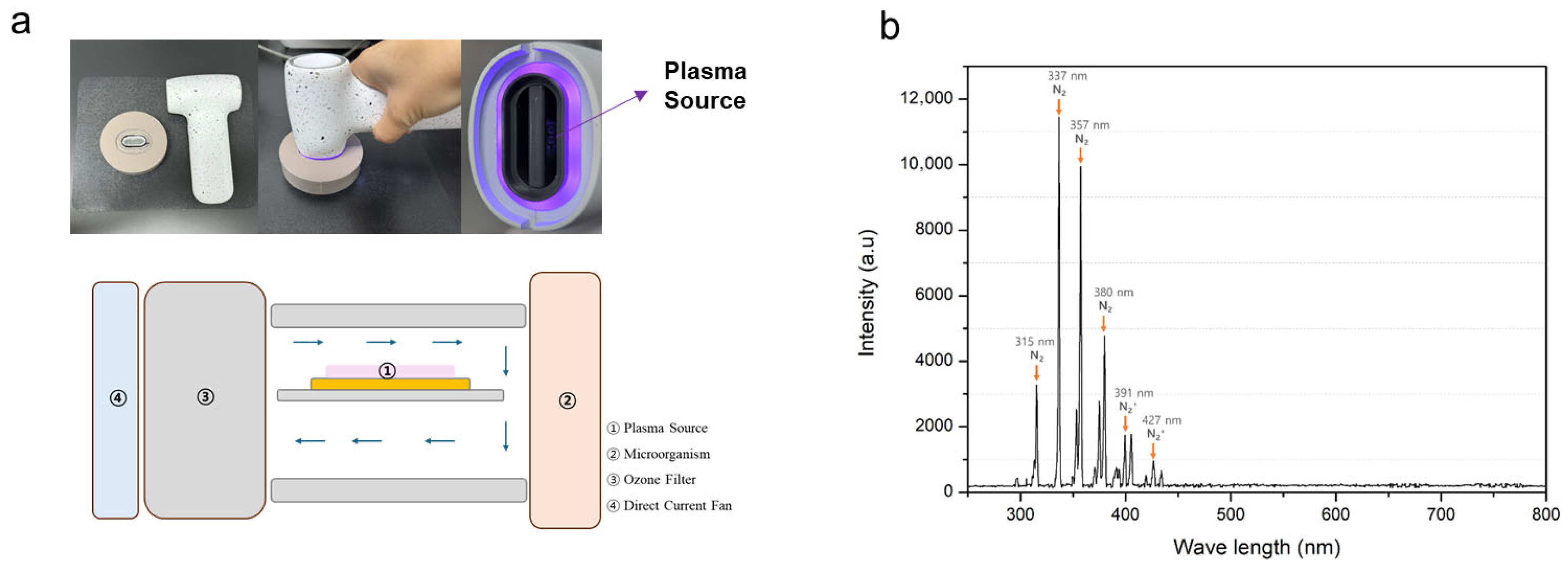

2.1. Air NCP Device

2.2. Optical Emission Spectroscopic Analysis of the Air NCP Device

2.3. Temperature and Ozone Measurements of the Air NCP Device

2.4. Cell Culture

2.5. Air NCP Treatment of Cells

2.6. Sulforhodamine B Assay

2.7. Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction

2.8. Western Blot Analysis

2.9. Prostaglandin E2 Assay

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Air NCP OES

3.2. Air NCP Temperature and Ozone Measurement

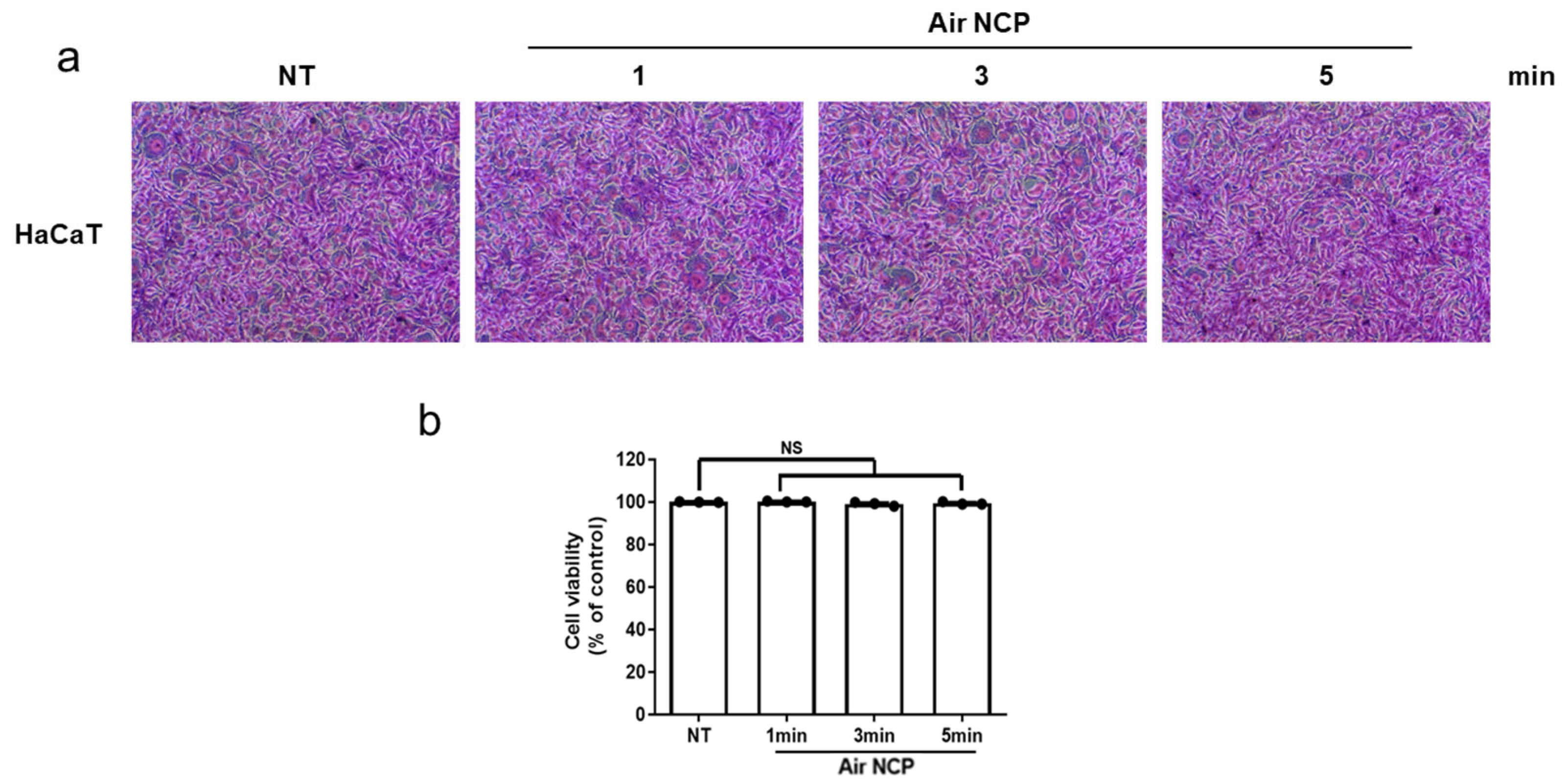

3.3. Effect of the Air NCP Device on HaCaT Cytotoxicity

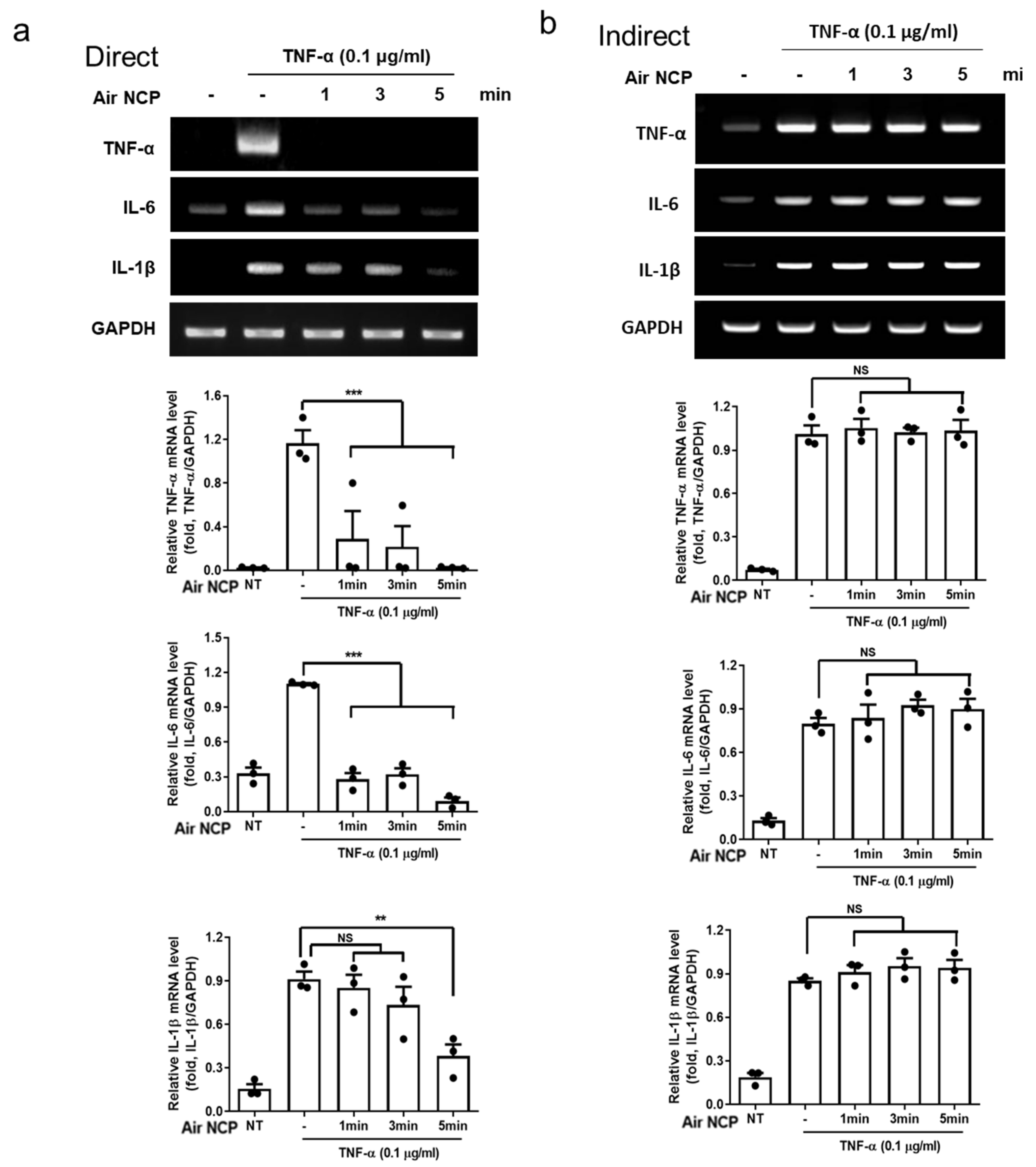

3.4. Effect of the Air NCP Device on the Expression of Inflammatory Cytokines

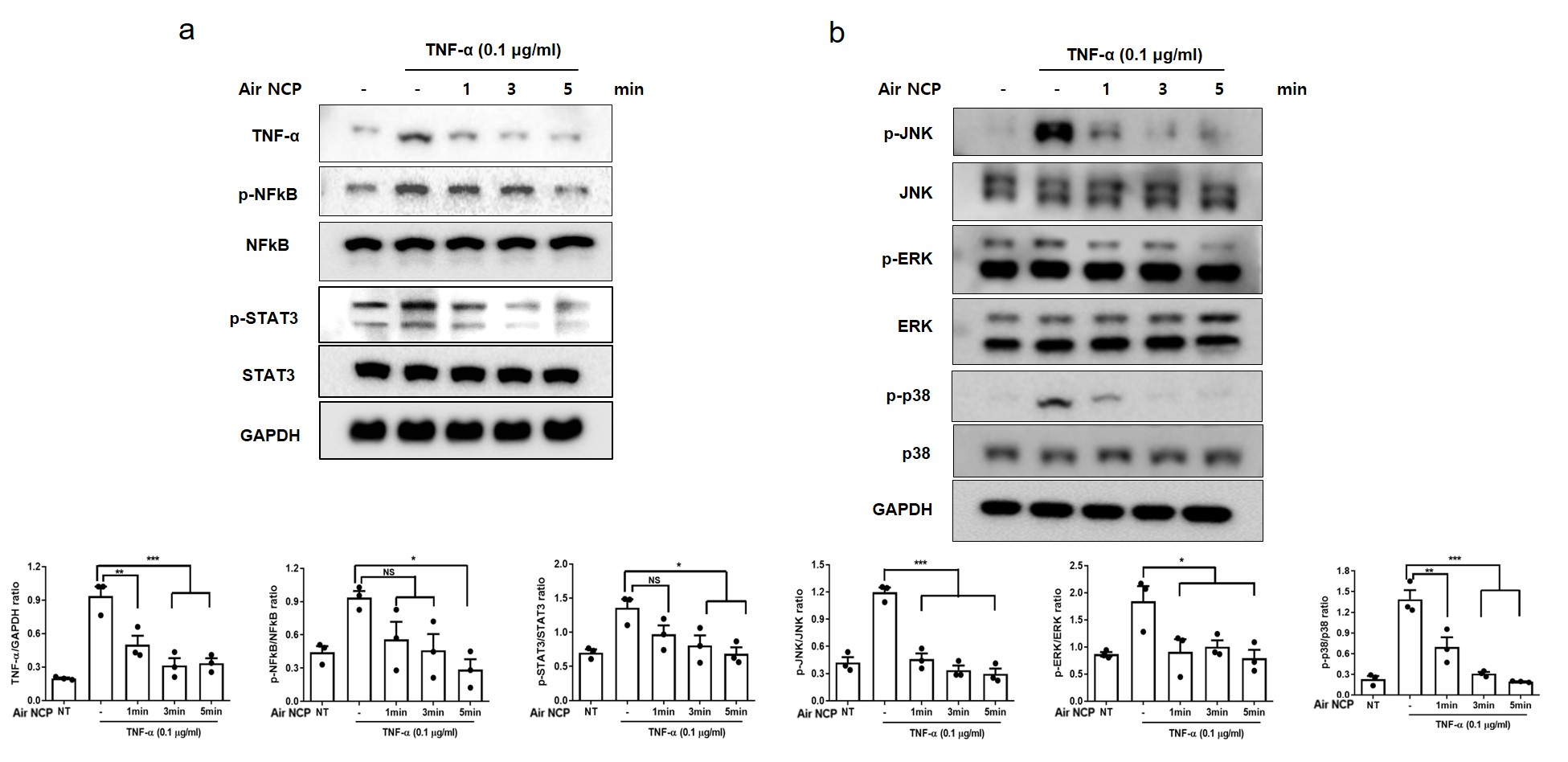

3.5. Effect of the Air NCP on Inflammation-Mediated Signaling

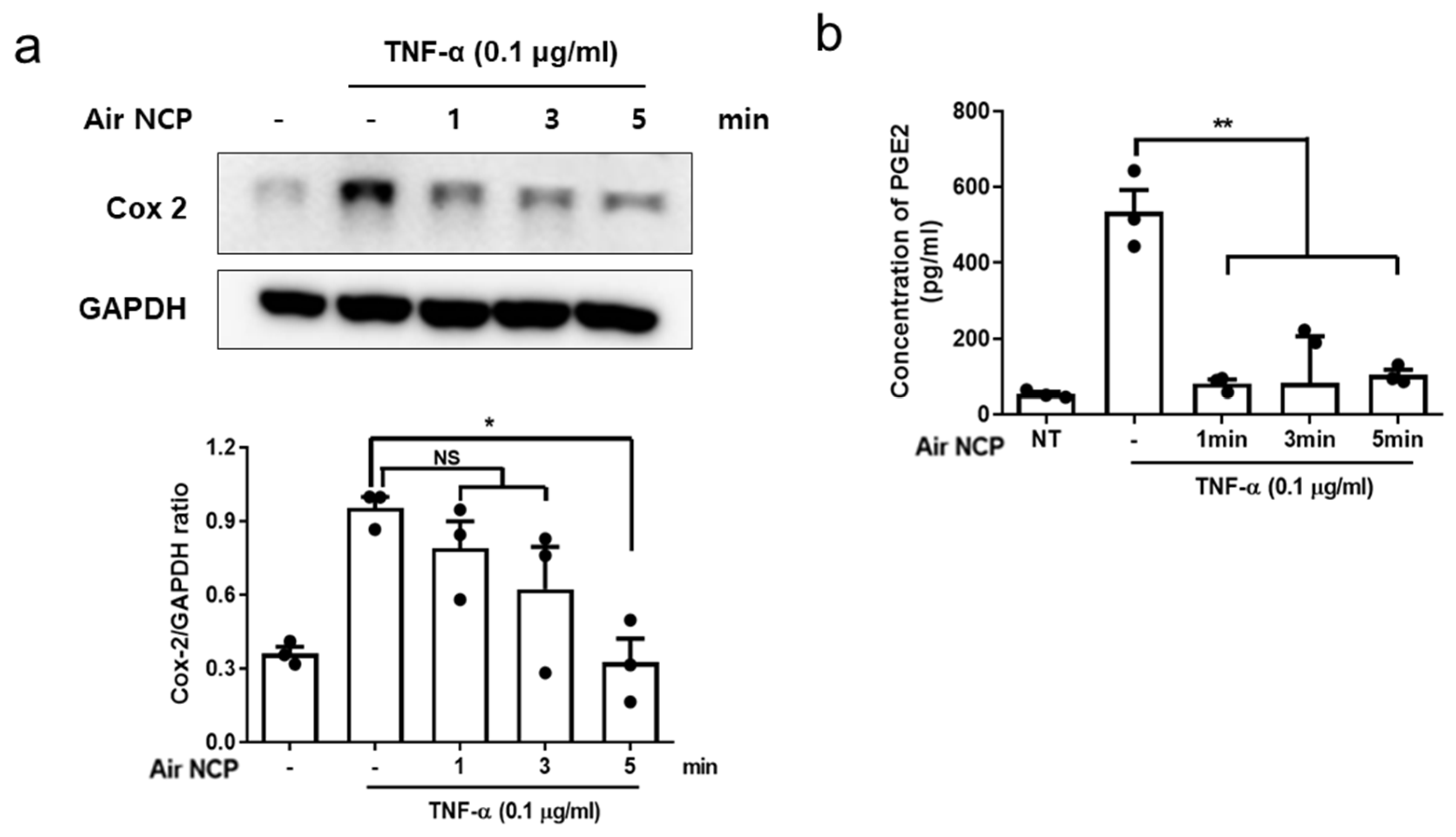

3.6. Effects of Air NCP on Cyclooxygenase-2 and Prostaglandin E2 Production

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HaCaT | Human keratinocytes |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| Air NCP | Non-ozone cold plasma device based on a wireless air source |

| p-NF-κB | Phosphorylated NF-κB |

| p-STAT3 | Phosphorylated STAT3 |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| SRB | Sulforhodamine B |

| TBS-T | Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

References

- Koberle, M.; Amar, Y.; Holge, I.; Kaesler, M.S.; Biedermann, T. Cutaneous barriers and skin immunity. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2022, 268, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Tsoi, L.C.; Billi, A.C.; Ward, N.L.; Harms, P.W.; Zeng, C.; Maverakis, E.; Kahlenberg, J.M.; Gudjonsson, J.E. Cytokinocytes: The diverse contribution of keratinocytes to immune responses in skin. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e142067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piipponen, M.; Li, D.; Landen, N.X. The immune functions of keratinocytes in skin wound healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.; Roan, F.; Ziegler, S.F. The atopic march: Current insights into skin barrier dysfunction and epithelial cell-derived cytokines. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 278, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.C.; Tominaga, M.; Kamata, Y.; Umehara, Y.; Matsuda, H.; Takahashi, N.; Kina, K.; Ogawa, M.; Ogawa, H.; Takamori, K. Possible antipruritic mechanism of cyclosporine A in atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2016, 96, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostrom, A.; Lindman, H.; Swartling, C.; Berne, B.; Bergh, J. Potent corticosteroid cream (mometasone furoate) significantly reduces acute radiation dermatitis: Results from a double-blind, randomized study. Radiother. Oncol. 2001, 59, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Acharjya, B. Adverse cutaneous drug reaction. Indian J. Dermatol. 2008, 53, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzano, A.V.; Borghi, A.; Cugno, M. Adverse drug reactions and organ damage: The skin. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2016, 28, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narla, S.; Silverberg, J.I.; Simpson, E.L. Management of inadequate response and adverse effects to dupilumab in atopic dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 86, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otlewska, A.; Baran, W.; Batycka-Baran, A. Adverse events related to topical drug treatments for acne vulgaris. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2020, 19, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, A.R.; Doherty, K.M.; Leggott, J.; Zlotoff, B. Cutaneous reactions to drugs in children. Pediatrics 2007, 120, e1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, Y.; Naganuma, A.; Suzuki, Y.; Uehara, S.; Hoshino, T.; Hatanaka, T.; Shibusawa, N.; Uehara, A.; Ogawa, A.; Kakizaki, S.; et al. Drug-induced steatohepatitis caused by long-term use of topical steroids for atopic dermatitis. Intern. Med. 2024, 63, 3165–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuguchi, A.; Nakajima, T.; Ishii, Y.; Yoshino, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Endo, K.; Shiko, Y.; Kawasaki, Y.; Amemiya, A.; Torikoe, M.; et al. Prevention of atopic dermatitis in babies by skin care from the newborn period. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 186, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J. Effects and mechanisms of non-thermal plasma-mediated ROS and its applications in animal husbandry and biomedicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalaf, A.T.; Abdalla, A.N.; Ren, K.; Liu, X. Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP): A revolutionary approach in dermatology and skincare. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, I.J.; Yun, M.R.; Yoon, H.K.; Lee, K.H.; Choi, S.Y.; Lee, W.J.; Chang, S.E.; Won, C.H. Treatment of atopic dermatitis using non-thermal atmospheric plasma in an animal model. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, T.; Feng, S.; Zhu, H.; Bai, R.; Gan, X.; He, K.; Du, W.; Cheng, B.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. Therapeutic potential of plasma-treated solutions in atopic dermatitis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 225, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Shui, R.; Chen, J. Plasma dermatology: Skin therapy using cold atmospheric plasma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 918484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubinova, S.; Zaviskova, K.; Uherkova, L.; Zablotskii, V.; Churpita, O.; Lunov, O.; Dejneka, A. Non-thermal air plasma promotes the healing of acute skin wounds in rats. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjunan, K.P.; Friedman, G.; Fridman, A.; Clyne, A.M. Non-thermal dielectric barrier discharge plasma induces angiogenesis through reactive oxygen species. J. R. Soc. Interface 2012, 9, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, H.J.; Won, H.R.; Kim, C.H. Non-thermal atmospheric plasma ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice through inhibition of immune responses and up-regulation of PD-L1 expression. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Liebelt, G.; Striesow, J.; Freund, E.; von Woedtke, T.; Wende, K.; Bekeschus, S. The molecular and physiological consequences of cold plasma treatment in murine skin and its barrier function. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 161, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, G.C.; Choi, J.H.; Hong, J.W. Plasma cupping induces VEGF expression in skin cells through nitric oxide-mediated activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchi, H.; Terao, H.; Koga, T.; Furue, M. Cytokines and chemokines in the epidermis. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2000, 24, S29–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauder, D.N. The role of epidermal cytokines in inflammatory skin diseases. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1990, 95, S27–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, D.-I.; Lee, A.-H.; Shin, H.-Y.; Song, H.-R.; Park, J.-H.; Kang, T.-B.; Lee, S.-R.; Yang, S.-H. The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α) in Autoimmune Disease and Current TNF-α Inhibitors in Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banno, T.; Gazel, A.; Blumenberg, M. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF alpha) in epidermal keratinocytes revealed using global transcriptional profiling. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 32633–32642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogle, M.A.; Arndt, K.A.; Dover, J.S. Evaluation of plasma skin regeneration technology in low-energy full-facial rejuvenation. Arch. Dermatol. 2007, 143, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.S.; Cho, Y.S.; Joo, S.Y.; Mun, C.H.; Seo, C.H.; Kim, J.B. Wound healing potential of low temperature plasma in human primary epidermal keratinocytes. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 16, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, H.J.; Han, C.H.; Kang, S.U.; Kim, C.H. Non-thermal plasma inhibits mast cell activation and ameliorates allergic skin inflammatory diseases in NC/Nga mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, U.; Kostenko, S.; Sveinbjørnsson, B. The role of mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinases (MAPKAPKs) in inflammation. Genes 2013, 4, 101–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, H. MAPK signal pathways in the regulation of cell proliferation in mammalian cells. Cell Res. 2002, 12, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, T.; Lin, K.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Hsia, C.-W.; Manubolu, M.; Huang, W.-C.; Sheu, J.-R.; Hsia, C.-H. Targeting MAPK/NF-κB pathways in anti-inflammatory potential of rutaecarpine: Impact on Src/FAK-mediated macrophage migration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.Y.; Pillinger, M.H.; Abramson, S.B. Prostaglandin E2 synthesis and secretion: The role of PGE2 synthases. Clin. Immunol. 2006, 119, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, K.; Hohjoh, H.; Inazumi, T.; Tsuchiya, S.; Sugimoto, Y. Prostaglandin E2-induced inflammation: Relevance of prostaglandin E receptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1851, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Shin, S.; Kim, H.; Han, S.; Kim, K.; Kwon, J.; Kwak, J.-H.; Lee, C.-K.; Ha, N.-J.; Yim, D.; et al. Anti-inflammatory function of arctiin by inhibiting COX-2 expression via NF-κB pathways. J. Inflamm. 2011, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | 21.3 | 22.7 | 21.4 | 21.8 | 23.6 | 22.16 ± 0.98 °C |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O3 level (ppm a) | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 ± 0.004 ppm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Choi, B.-B.; Park, S.-A.; Choi, J.-H.; Kim, M.-K.; Choi, Y.D.; Lee, H.W.; Kim, G.-C. Inhibition of Inflammation by an Air-Based No-Ozone Cold Plasma in TNF-α-Induced Human Keratinocytes: An In Vitro Study. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010084

Choi B-B, Park S-A, Choi J-H, Kim M-K, Choi YD, Lee HW, Kim G-C. Inhibition of Inflammation by an Air-Based No-Ozone Cold Plasma in TNF-α-Induced Human Keratinocytes: An In Vitro Study. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010084

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Byul-Bora, Seung-Ah Park, Jeong-Hae Choi, Min-Kyeong Kim, Yoon Deok Choi, Hae Woong Lee, and Gyoo-Cheon Kim. 2026. "Inhibition of Inflammation by an Air-Based No-Ozone Cold Plasma in TNF-α-Induced Human Keratinocytes: An In Vitro Study" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010084

APA StyleChoi, B.-B., Park, S.-A., Choi, J.-H., Kim, M.-K., Choi, Y. D., Lee, H. W., & Kim, G.-C. (2026). Inhibition of Inflammation by an Air-Based No-Ozone Cold Plasma in TNF-α-Induced Human Keratinocytes: An In Vitro Study. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010084