Nobiletin Attenuates Adipogenesis and Promotes Browning in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes Through Exosomal miRNA-Mediated AMPK Activation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

2.2. Cell Viability Assay

2.3. Cell Culture and Differentiation of Preadipocytes

2.4. Lipid Quantification

2.5. Quantification of Gene Expression

2.6. Protein Quantification and Immunoblot Analysis

2.7. Exosome Purification and Exosomal Marker Study

2.8. microRNA RNA-Seq Analysis

2.9. Validation of microRNA

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Nobiletin Concentration Affecting the Survival of 3T3-L1 Adipocytes

3.2. Reduction of Intracellular Lipid Accumulation in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes in the Presence of Nobiletin

3.3. Suppression of Adipogenic Transcription Factors by Nobiletin

3.4. Inhibition of the Fatty Acid Synthesis Enzyme by Nobiletin

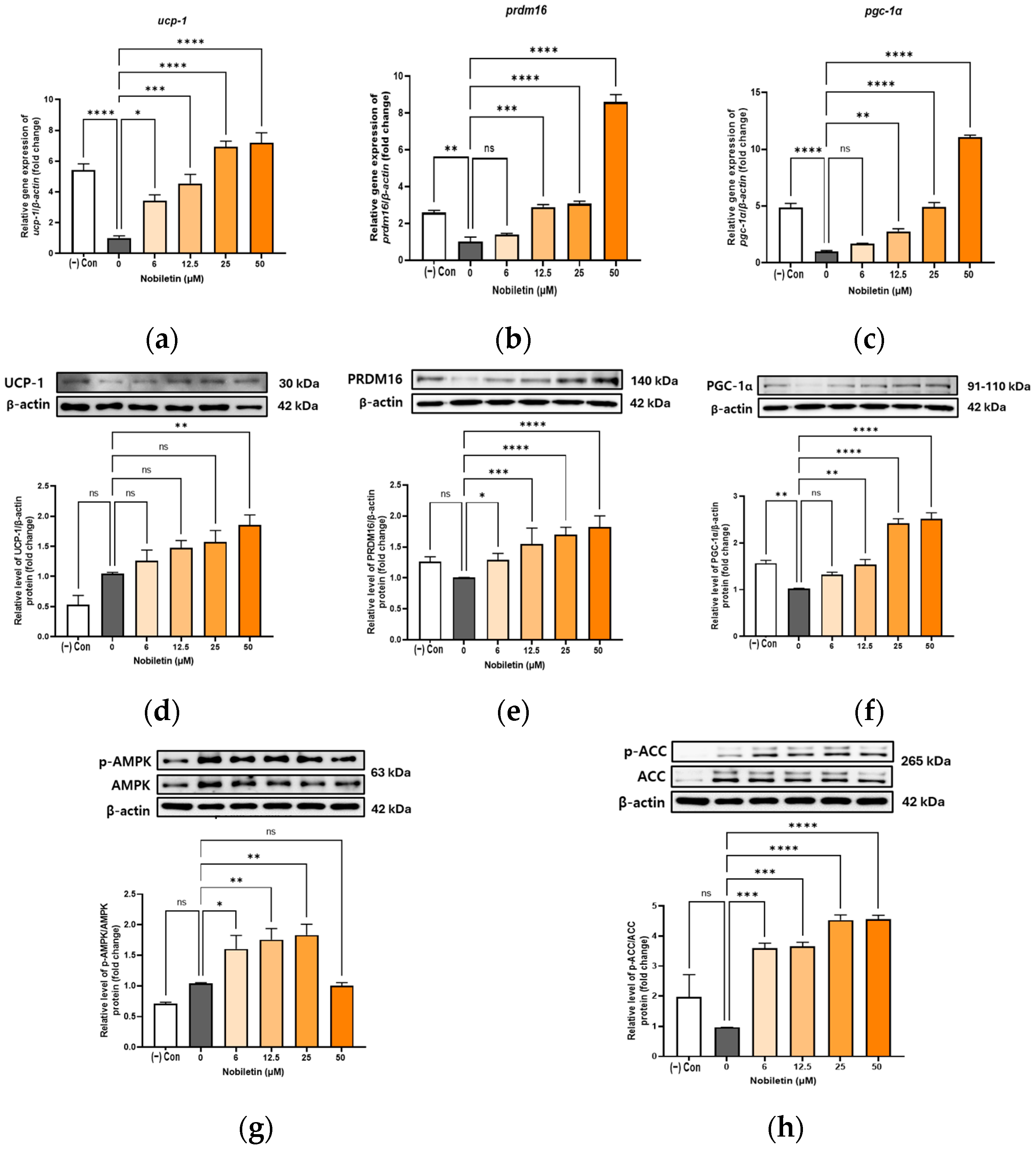

3.5. Increase in the Expression of Browning Markers in Differentiated Adipocytes 3T3-L1 in the Presence of Nobiletin

3.6. Activation of AMPK and ACC by Nobiletin in 3T3-L1 Cells

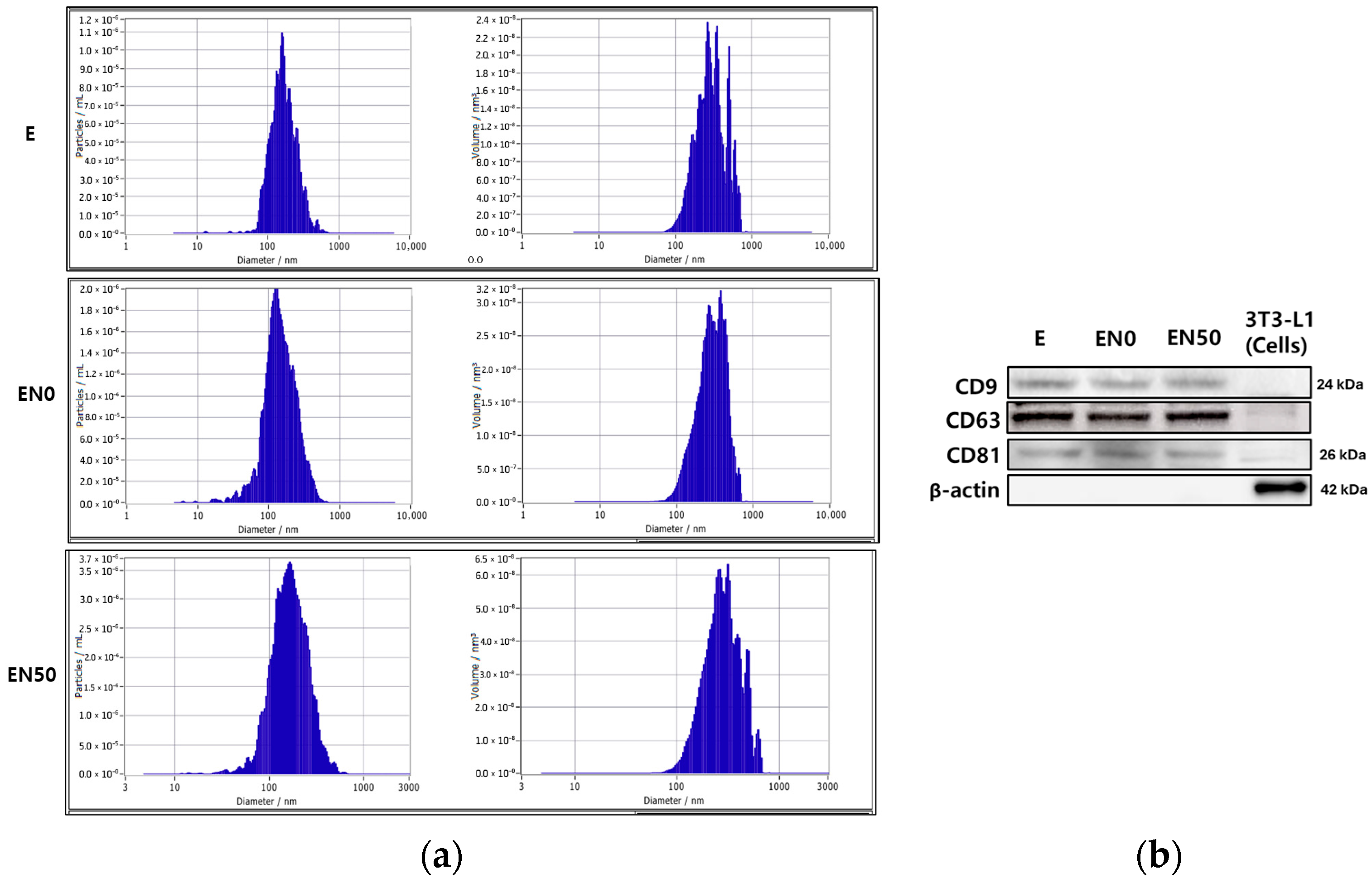

3.7. Exosome Extraction, Size, Concentration, and Markers

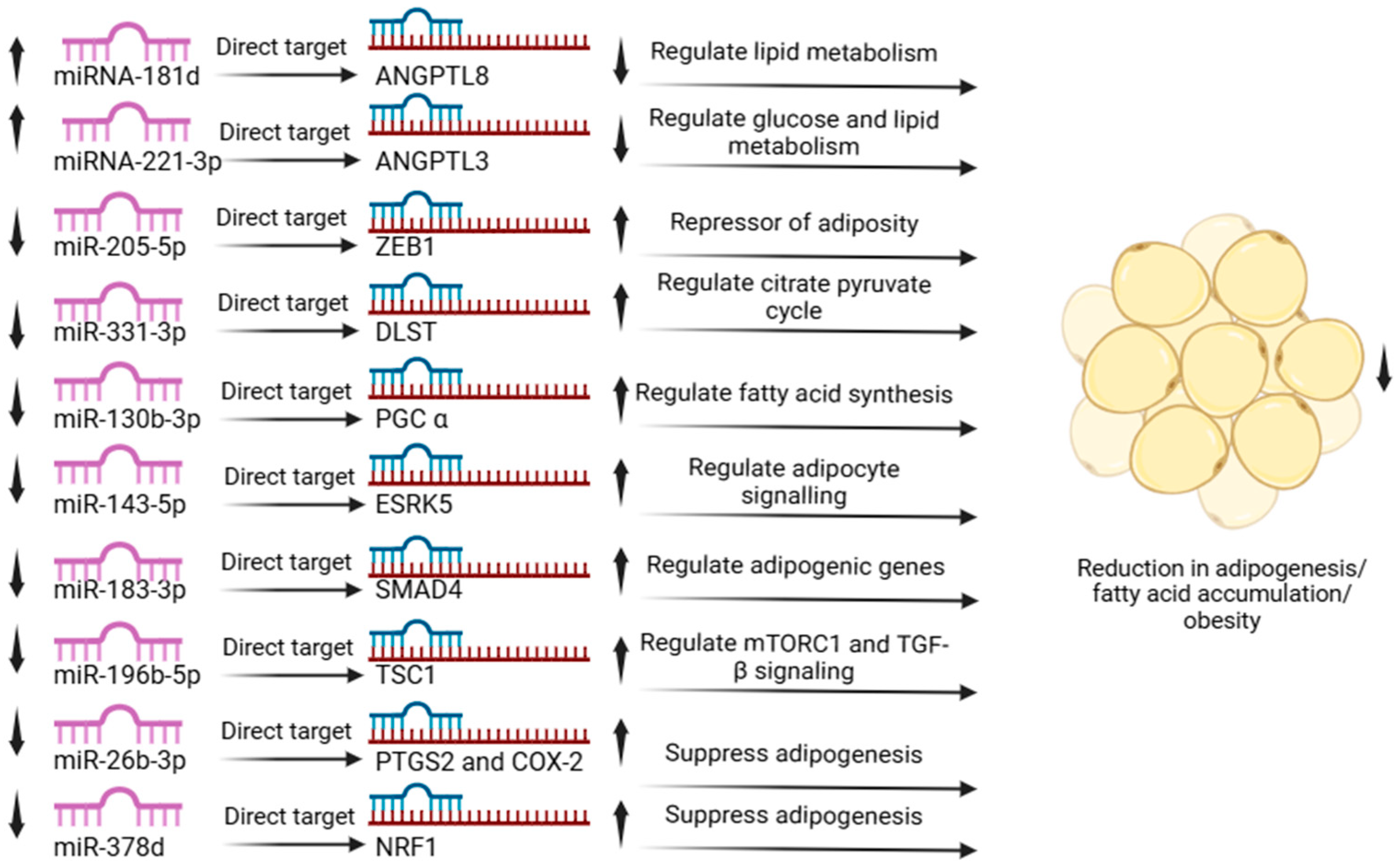

3.8. Expression Analysis of microRNA

3.9. Validation of Expressed microRNAs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Phelps, N.H.; Singleton, R.K.; Zhou, B.; Heap, R.A.; Mishra, A.; Bennett, J.E.; Paciorek, C.J.; Lhoste, V.P.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Stevens, G.A.; et al. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2024, 403, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; An, J.; Ha, S.Y.; Nam, S.; Kim, J.H. Immune signature as a potential marker for predicting response to immunotherapy in obesity-associated colorectal cancer. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 37, 1579–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.R.; Shin, J.; Han, K.; Chang, J.; Jeong, S.-M.; Chon, S.J.; Choi, S.J.; Shin, D.W. Obesity and Risk of Diabetes Mellitus by Menopausal Status: A Nationwide Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.J.; Park, S.; Kim, S.S.; Park, H.J.; Son, J.W.; Lee, T.K.; Hong, S.; Kang, J.-H.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, Y.-H.; et al. The Gangwon Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome Study: Methods and Initial Baseline Data. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2022, 31, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, V.; Lee, M.-J.; Chun, J.L.; Park, M.; Lee, H.-J. 1-Deoxynojirimycin containing Morus alba leaf-based food modulates the gut microbiome and expression of genes related to obesity. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Mawatari, K.; Yoo, S.-H.; Chen, Z. The Circadian Nobiletin-ROR Axis Suppresses Adipogenic Differentiation and IκBα/NF-κB Signaling in Adipocytes. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, V.; Chauhan, S.; Lee, H.-J. The Bioactivity and Phytochemicals of Pachyrhizus erosus (L.) Urb.: A Multifunctional Underutilized Crop Plant. Antioxidants 2021, 11, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, V.; Park, M.; Lee, H.-J. Comparative transcriptome analysis of the expression of antioxidant and immunity genes in the spleen of a Cyanidin 3-O-Glucoside-treated alzheimer’s mouse model. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, V.; Lee, H.-J. Antioxidant activity of Urtica dioica: An important property contributing to multiple biological activities. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, V.; Lee, H.-J. Pharmacological Activities of Mogrol: Potential Phytochemical against Different Diseases. Life 2023, 13, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, S.; Jaiswal, V.; Cho, Y.-I.; Lee, H.-J. Biological Activities and Phytochemicals of Lungworts (Genus Pulmonaria) Focusing on Pulmonaria officinalis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, V.; Lee, H.-J. Pharmacological Properties of Shionone: Potential Anti-Inflammatory Phytochemical against Different Diseases. Molecules 2023, 29, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, V.; Lee, H.-J. The Bioactivity and Phytochemicals of Muscari comosum (Leopoldia comosa), a Plant of Multiple Pharmacological Activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Jaiswal, V.; Kim, K.; Chun, J.; Lee, M.J.; Shin, J.H.; Lee, H.-J. Mulberry Leaf Supplements Effecting Anti-Inflammatory Genes and Improving Obesity in Elderly Overweight Dogs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jaglan, P.; Buttar, H.S. Nobiletin Prevents Obesity-Related Complications and Neurological Disorders: An Overview of Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Manag. 2023, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer Sost, M.; Stevens, Y.; Salden, B.; Troost, F.; Masclee, A.; Venema, K. Citrus Extract High in Flavonoids Beneficially Alters Intestinal Metabolic Responses in Subjects with Features of Metabolic Syndrome. Foods 2023, 12, 3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, D.; Jeong, H.; Kim, C.-E.; Leem, J. A System-Level Mechanism of Anmyungambi Decoction for Obesity: A Network Pharmacological Approach. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, M.; Slack, F.J. Challenges identifying efficacious miRNA therapeutics for cancer. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2020, 15, 987–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.D.; Kim, Y.; Choi, S.A.; Han, I.; Yadav, D.K. Clinical Significance of MicroRNAs, Long Non-Coding RNAs, and CircRNAs in Cardiovascular Diseases. Cells 2023, 12, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoumi, M.; Arafa, M.G.; Nasr, M.; Sammour, O.A. Nobiletin-loaded composite penetration enhancer vesicles restore the normal miRNA expression and the chief defence antioxidant levels in skin cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-G.; Jian, W.-J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Nobiletin promotes the pyroptosis of breast cancer via regulation of miR-200b/JAZF1 axis. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2021, 37, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Iqbal, H.; Kim, S.M.; Jin, M. Phytochemicals that act on synaptic plasticity as potential prophylaxis against stress-induced depressive disorder. Biomol. Ther. 2023, 31, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.S.; Farhana, A.; Mohammed, G.E.Y.; Osman, A.A.; Alsrhani, A.; Shahid, S.M.A.; Kuddus, M.; Rasheed, Z. Thymoquinone Upregulates microRNA-199a-3p and Downregulates COX-2 Expression and PGE(2) Production via Deactivation of p38/ERK/JNK-MAPKs and p65/p50-NF-κB Signaling in Human Lung Cancer Cells. Biology 2025, 14, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sp, N.; Kang, D.Y.; Lee, J.-M.; Jang, K.-J. Mechanistic Insights of Anti-Immune Evasion by Nobiletin through Regulating miR-197/STAT3/PD-L1 Signaling in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, N.M.; Burke, A.C.; Samsoondar, J.P.; Seigel, K.E.; Wang, A.; Telford, D.E.; Sutherland, B.G.; O’Dwyer, C.; Steinberg, G.R.; Fullerton, M.D.; et al. The citrus flavonoid nobiletin confers protection from metabolic dysregulation in high-fat-fed mice independent of AMPK. J. Lipid Res. 2020, 61, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martchenko, A.; Biancolin, A.D.; Martchenko, S.E.; Brubaker, P.L. Nobiletin ameliorates high fat-induced disruptions in rhythmic glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuk, T.; Kim, Y.; Yang, J.; Sung, J.; Jeong, H.S.; Lee, J. Nobiletin Inhibits Hepatic Lipogenesis via Activation of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 2018, 7420265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Song, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Z.; Raza, S.H.A.; Jiang, C.; Ma, Y.; Ma, Y.; et al. Regulatory role of exosome-derived miRNAs and other contents in adipogenesis. Exp. Cell Res. 2024, 441, 114168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Abe, D.; Sekiya, K. Nobiletin enhances differentiation and lipolysis of 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 357, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, J.; Parray, H.A.; Yun, J.W. Nobiletin induces brown adipocyte-like phenotype and ameliorates stress in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biochimie 2018, 146, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Sato, T.; Murotomi, K. Sudachitin and Nobiletin Stimulate Lipolysis via Activation of the cAMP/PKA/HSL Pathway in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Foods 2023, 12, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen-Urstad, A.P.L.; Semenkovich, C.F. Fatty acid synthase and liver triglyceride metabolism: Housekeeper or messenger? Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2012, 1821, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J. Brown Adipose Tissue: Function and Physiological Significance. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 277–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seale, P.; Kajimura, S.; Yang, W.; Chin, S.; Rohas, L.M.; Uldry, M.; Tavernier, G.; Langin, D.; Spiegelman, B.M. Transcriptional Control of Brown Fat Determination by PRDM16. Cell Metab. 2007, 6, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.-H.; Singh, S.P.; Raffaele, M.; Waldman, M.; Hochhauser, E.; Ospino, J.; Arad, M.; Peterson, S.J. Adipocyte-Specific Expression of PGC1α Promotes Adipocyte Browning and Alleviates Obesity-Induced Metabolic Dysfunction in an HO-1-Dependent Fashion. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahonen, M.; Taskinen, J.; Latorre, J.; Ortega, F.; Pa, N.; Olkkonen, V. Microrna-221-3P alters human adipocyte lipid storage by regulating glucose and lipid metabolism. Atherosclerosis 2020, 315, e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Farha, M.; Cherian, P.; Al-Khairi, I.; Nizam, R.; Alkandari, A.; Arefanian, H.; Tuomilehto, J.; Al-Mulla, F.; Abubaker, J. Reduced miR-181d level in obesity and its role in lipid metabolism via regulation of ANGPTL3. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.-F.; Qiang, J.; Bao, J.-W.; Li, H.-X.; Yin, G.-J.; Xu, P.; Chen, D.-J. miR-205-5p negatively regulates hepatic acetyl-CoA carboxylase β mRNA in lipid metabolism of Oreochromis niloticus. Gene 2018, 660, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Cui, J.; Ma, L.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, W. The Effect of MicroRNA-331-3p on preadipocytes proliferation and differentiation and fatty acid accumulation in Laiwu pigs. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 9287804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jazii, F.R.; Haghighi, M.M.; Alvares, D.; Liu, L.; Khosraviani, N.; Adeli, K. miR-130b is a potent stimulator of hepatic very-low-density lipoprotein assembly and secretion via marked induction of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 318, E262–E275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, Z.-Q.; Wang, Y.-J.; Wang, M.; Yang, W.-C. MiR-143 regulates milk fat synthesis by targeting Smad3 in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Animals 2020, 10, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhong, T.; Wang, L.; Guo, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, H. MiR-183 promotes preadipocyte differentiation by suppressing Smad4 in goats. Gene 2018, 666, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Wang, B. miR-196b-5p controls adipocyte differentiation and lipogenesis through regulating mTORC1 and TGF-β signaling. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 9207–9222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Ji, C.; Song, G.; Shi, C.; Shen, Y.; Chen, L.; Yang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, X. Obesity-associated microRNA-26b regulates the proliferation of human preadipocytes via arrest of the G1/S transition. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 3648–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Hu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, Z.; Niu, J.; Steer, C.J.; Zheng, G.; Song, G. MicroRNA-378 promotes hepatic inflammation and fibrosis via modulation of the NF-κB-TNFα pathway. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, K.; Nishi, K.; Kadota, A.; Nishimoto, S.; Liu, M.-C.; Sugahara, T. Nobiletin suppresses adipocyte differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells by an insulin and IBMX mixture induction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2012, 1820, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, Y.; Ham, H.; Park, Y.; Jeong, H.-S.; Lee, J. Nobiletin suppresses adipogenesis by regulating the expression of adipogenic transcription factors and the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 12843–12849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-S.; Cha, B.-Y.; Choi, S.-S.; Choi, B.-K.; Yonezawa, T.; Teruya, T.; Nagai, K.; Woo, J.-T. Nobiletin improves obesity and insulin resistance in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, N.M.; Trzaskalski, N.A.; Hanson, A.A.; Fadzeyeva, E.; Telford, D.E.; Chhoker, S.S.; Sutherland, B.G.; Edwards, J.Y.; Huff, M.W.; Mulvihill, E.E. Nobiletin prevents high-fat diet-induced dysregulation of intestinal lipid metabolism and attenuates postprandial lipemia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2022, 42, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Tian, X.; Gan, L.; Yang, X. Nobiletin promotes adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells through the activation of Akt. Adv. Tradit. Med. 2021, 23, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, M.; Roder, K.; Zhang, L.; Wolf, S. Transcription factors acting on the promoter of the rat fatty acid synthase gene. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002, 30, 1070–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Shan, S.; Li, P.-P.; Shen, Z.-F.; Lu, X.-P.; Cheng, J.; Ning, Z.-Q. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ transcriptionally up-regulates hormone-sensitive lipase via the involvement of specificity protein-1. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Roda, P.; Perez-Navarro, E.; Garcia-Martin, R. Adipose Tissue as a Major Launch Spot for Circulating Extracellular Vesicle-Carried MicroRNAs Coordinating Tissue and Systemic Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Luo, L.; Luo, Y.; Wu, D.; Spilca, D.; Le, Q.; Yang, X.; Alvarez, K.; Hines, W.C.; et al. COX-2 Deficiency Promotes White Adipogenesis via PGE2-Mediated Paracrine Mechanism and Exacerbates Diet-Induced Obesity. Cells 2022, 11, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banhos Danneskiold-Samsøe, N.; Sonne, S.B.; Larsen, J.M.; Hansen, A.N.; Fjære, E.; Isidor, M.S.; Petersen, S.; Henningsen, J.; Severi, I.; Sartini, L.; et al. Overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 in adipocytes reduces fat accumulation in inguinal white adipose tissue and hepatic steatosis in high-fat fed mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhao, X.; Steer, C.J.; Yan, G.; Song, G. A negative feedback loop between microRNA-378 and Nrf1 promotes the development of hepatosteatosis in mice treated with a high fat diet. Metabolism 2018, 85, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| PPARγ | TTTTCAAGGGTGCCAGTTTC | AATCCTTGGCCCTCTGAGAT |

| C/EBPα | TTACAACAGGCCAGGTTTCC | GGCTGGCGACATACAGTACA |

| SREBP-1c | TGTTGGCATCCTGCTATCTG | AGGGAAAGCTTTGGGGTCTA |

| FAS | TTGCTGGCACTACAGAATGC | AACAGCCTCAGAGCGACAAT |

| PGC-1α | GCAACATGCTCAAGCCAAAC | TGCAGTTCCAGAGAGTTCCA |

| UCP-1 | CTTTGCCTCACTCAGGATTGG | ACTGCCACACCTCCAGTCATT |

| PRDM16 | CAGCACGGTGAAGCCATTC | GCGTGCATCCGCTTGTG |

| β-actin | CTGTCCCTGTATGCCTCTG | ATGTCACGCACGATTTCC |

| microRNA | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| miR-221-3p | GCAGAGCTACATTGTCTGCT | CAGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGAAACCCA |

| miR-181d | ACACTCCAGCTGGGAACATTCATTGTTGTC | TCAACTGGTGTCGTGGAGTCGGCAATTCAG-TTGAGACCCACCG |

| miR-205-5p | TCCTTCATTCCACCGGAGTCTG | GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGAC |

| miR-331-3p | ACACTCCAGCTGGGGCCCCTGGGCCTATC | CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGAGTCGGCAATTCAGTTGAGTTCTAGGA |

| miR-130b-3p | CAGTGCAATGATGAAAGGGCAT | ATGCCCTTTCATCATTGCACTG |

| miR-143-5p | GCGCAGCGCCCTGTCTCC | GCTGCAGAACAACTTCTC |

| miR-183-3p | CGCAGAGTGTGACTCCTGTT | TGGCCCTTCGGTAATTCACT |

| miR-196b-5p | ACACTCCAGCTGGGTAGGTAGTTTCCTGTT | CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGAGTCGGCAATTCA-GTTGAGCCCAACAA |

| miR-26b-3p | GGCCTGTTCTCCATTACTTGG | CGCTTCACGAATTTGCGTGTCAT |

| miR-378 | GGACACTGGACTTGGAG | TGCGTGTCGTGGAGTC |

| U6 | CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA | ACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chauhan, S.; Baek, H.; Jaiswal, V.; Park, M.; Lee, H.-J. Nobiletin Attenuates Adipogenesis and Promotes Browning in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes Through Exosomal miRNA-Mediated AMPK Activation. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010036

Chauhan S, Baek H, Jaiswal V, Park M, Lee H-J. Nobiletin Attenuates Adipogenesis and Promotes Browning in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes Through Exosomal miRNA-Mediated AMPK Activation. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleChauhan, Shweta, Hana Baek, Varun Jaiswal, Miey Park, and Hae-Jeung Lee. 2026. "Nobiletin Attenuates Adipogenesis and Promotes Browning in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes Through Exosomal miRNA-Mediated AMPK Activation" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010036

APA StyleChauhan, S., Baek, H., Jaiswal, V., Park, M., & Lee, H.-J. (2026). Nobiletin Attenuates Adipogenesis and Promotes Browning in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes Through Exosomal miRNA-Mediated AMPK Activation. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010036