A Conceptual Model for Developing Digital Maturity in Hospitality Micro and Small Enterprises

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Maturity

2.2. Digital Transformation in Hospitality

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Dimensions of Digital Maturity

4.1. Strategy and Organization

“Each product has a suitable digital marketing and promotion method, and marketing and promotion are dynamic and changing. … The strategies for high-end, mid-range, and low-end products are all different, and the product determines the marketing method.”(No. H4)

4.2. Digital Technology

“We have our own marketing channel matrix, including many self-media operating accounts and light application. Mainly because we have accumulated many customers, we have a strong foundation. And we have [formed alliances with] companies along a travel line in the northwest of Yunnan Province to promote together.”(No. 22)

“We used intelligent furniture earlier than large hotels, such as smart curtains, automatic air conditioning, TV management, humidifier management… many tourists choose to stay in our inn because of our facilities.”(No. 4)

4.3. Digital Capabilities

“We received many orders at the beginning. When two platforms handle orders simultaneously, it’s easy to duplicate orders. After a few duplicates, my father complained. Then, the photographer we hired suggested using a cloud manager.”(No. 15)

“[The online booking platform] has red lines that cannot be crossed, such as rejecting orders or converting a booking made on the platform into an off-platform booking. In addition, timely responses are required, and negative reviews need to be responded to promptly. Also, the room images should be exquisite and showcase the unique features of the inn, which will make it easier for guests to click through.”(No. 20)

“Ctrip provides a lot of data, and we do use this big data to make decisions. For example, they even provide us with a user profile, including which provinces your orders come from, and we will adjust accordingly based on this information.”(No. 3)

“Around seven or eight years ago, our customers mostly came through Ctrip and Meituan. … A WeChat Official Account was quite effective four or five years ago. If you performed well on a WeChat Official Account in 2015, you could generate almost half of the revenue. … [Now], the influence of TikTok is rising rapidly.”(No. 4)

“Every product has a unique marketing method. … Holiday inns, B&Bs, [and] homestays represent a non-standardized market. There is no conclusive way to saturate this niche market with a one-size-fits-all solution. You cannot summarize the hospitality MSE market with a unified model. … Choosing an individualized approach based on your own product is pivotal.”(No. H3)

“We have our own marketing matrix, comprising channels such as Today’s Headlines, Meituan, Feizhu, Douban, TikTok, Little Red Book, WeChat Official Account, Phoenix Net, Baidu Baijia, and even Xuexi Qiangguo.”(No. 15)

4.4. Integrated business

“If we digitize our business—for example, with a good room management system—it can see the occupancy situation and arrange room assignments well. It can connect directly to various platforms, such as Ctrip, without having to operate room switches, and it has a clear statistical report, so there is no need for manual bookkeeping.”(No. 15)

“I usually post content once every two weeks on WeChat Moments… I get more than 10,000 RMB in revenue per month from WeChat.”(No. 7)

“We provide excellent service and offer affordable routes. Our customers are all satisfied, except for one negative review. We also had a guest who wrote a travel blog, which was unexpectedly exciting. Her blog was promoted to the top on Ctrip; thus, many people came to stay at our homestay.”(No. 1)

“Nowadays, it is difficult to find talent through apps like 58.com. However, if you show your business culture through platforms like TikTok, Weibo, and Little Red Book, while presenting the unique characteristics of your company, you will find that you can attract staff who are compatible with the corporate culture or temperament.”(No. 4)

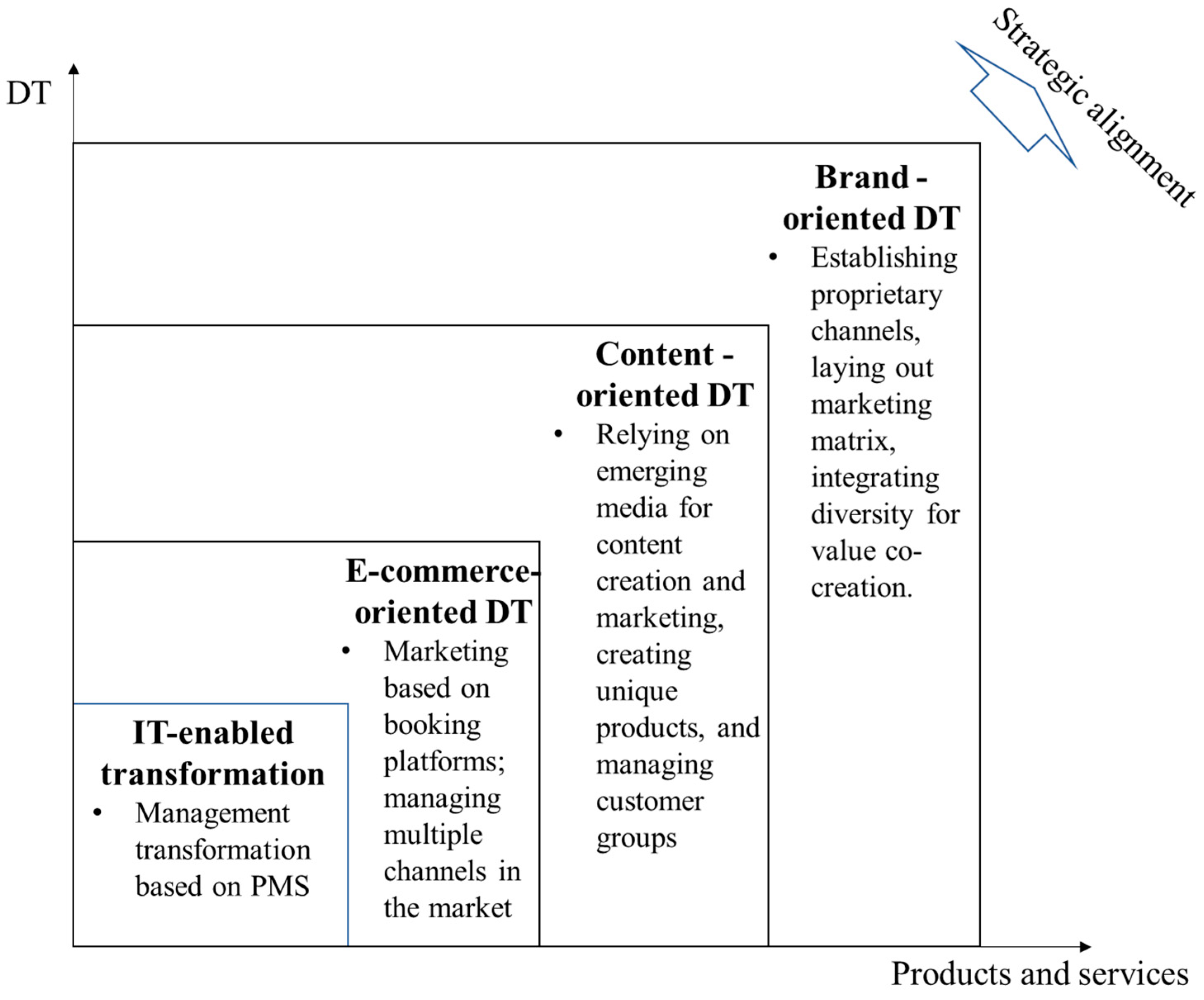

5. Digital Maturity Development Phases

“Holiday MSEs themselves are non-standard accommodations. If I have an ordinary homestay client, to be honest, I might only work on their Ctrip optimization and training rather than recommending [that they engage in] content marketing. This is because the input–output ratio of high-priced new media is too low for low-priced homestays.”(No. H3)

6. Discussion and Conclusions

7. Contributions, Implications, and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Number | Gender | Education | Position | Business Scale (Room Quantity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | female | Bachelor | Owner | 8 |

| 2 | female | Junior high school | Owner | 15 |

| 3 | female | Master | Owner | 8 |

| 4 | male | Bachelor | Owner | 30 |

| 5 | male | Bachelor | Owner | 15 |

| 6 | female | Bachelor | Owner | 10 |

| 7 | male | Bachelor | Manager | 40 |

| 8 | female | Bachelor | Owner | 10 |

| 9 | male | High school | Owner | 15 |

| 10 | male | Bachelor | Owner | 30 |

| 11 | female | Junior college | Owner | 12 |

| 12 | male | Bachelor | Owner | 18 |

| 13 | male | Bachelor | Owner | 16 |

| 14 | male | Junior college | Manager | 20 |

| 15 | female | Bachelor | Owner | 15 |

| 16 | female | Bachelor | Owner | 16 |

| 17 | male | High school | Owner | 12 |

| 18 | male | Bachelor | Owner | 30 |

| 19 | male | Bachelor | Owner | 16 |

| 20 | male | Bachelor | Manager | 18 |

| 21 | female | High school | Owner | 15 |

| 22 | male | Bachelor | Owner | 22 |

| 23 | male | Junior college | Manager | 16 |

| 24 | female | Bachelor | Owner | 32 |

| 25 | female | Junior college | Owner | 28 |

| 26 | female | Bachelor | Owner | 27 |

| 27 | female | Junior college | Manager | 11 |

| 28 | female | Bachelor | Manager | 8 |

| H1 | male | Bachelor | Industry Association Manager | N/A |

| H2 | female | Bachelor | Consultant | N/A |

| H3 | male | Bachelor | Consultant | N/A |

| H4 | male | Bachelor | Consultant | N/A |

| H5 | female | Master | Industry Association Manager | N/A |

| H6 | male | Bachelor | Consultant | N/A |

| H7 | male | Bachelor | Consultant | N/A |

References

- Shin, H.; Perdue, R.R. Customer Nontransactional Value Cocreation in an Online Hotel Brand Community: Driving Motivation, Engagement Behavior, and Value Beneficiary. J. Travel Res. 2021, 61, 1088–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, V.; Srivastava, S. Hospitality and hospitality industry amid COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives on challenges and learnings from India. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M.; Fathi, M. Corporate survival in Industry 4.0 era: The enabling role of lean digitized manufacturing. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 31, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.; Law, R. Readiness of upscale and luxury-branded hotels for digital transformation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 79, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassnig, M.; Muller, J.M.; Klieber, K.; Zeisler, A.; Schirl, M. A digital readiness check for the evaluation of supply chain aspects and company size for Industry 4.0. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2022, 33, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.R.; Salume, P.K.; Barbosa, M.W.; de Sousa, P.R. The path to digital maturity: A cluster analysis of the retail industry in an emerging economy. Technol. Soc. 2023, 72, 102191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, G.; Palmer, D.; Phillips, A.; Kiron, D.; Buckley, N. Achieving Digital Maturity. 2017. Available online: https://hbsp.harvard.edu/product/SMR624-PDF-ENG (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Rossmann, A. Digital maturity: Conceptualization and measurement model. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Information Systems, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–16 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, R.C.; Martinho, J.L. An Industry 4.0 maturity model proposal. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2020, 31, 1023–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassanelli, C.; Rossi, M.; Terzi, S. Evaluating the smart readiness and maturity of manufacturing companies along the product development process. In PLM 2019: Product Lifecycle Management in the Digital Twin Era; Fortin, C., Rivest, L., Bernard, A., Bouras, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 565, pp. 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bouncken, R.; Barwinski, R. Shared digital identity and rich knowledge ties in global 3D printing—A drizzle in the clouds? Glob. Strateg. J. 2020, 11, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beliaeva, T.; Ferasso, M.; Kraus, S.; Damke, E.J. Dynamics of digital entrepreneurship and the innovation ecosystem. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 26, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillis, I.; Wagner, B. E-business development: An exploratory investigation of the small firm. Int. Small Bus. J. 2005, 23, 604–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghaus, S.; Back, A. Stages in digital business transformation: Results of an empirical maturity study. In Proceedings of the Tenth Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems, Paphos, Cyprus, 4–6 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Neuland. Digital Transformation Report 2015. 2015. Available online: http://www.neuland.digital/neuland/wpcontent/uploads/2016/01/DTA_Report_2015.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Chanias, S.; Hess, T. How Digital Are We? Maturity Models for the Assessment of a Company’s Status in the Digital Transformation. 2016. Available online: http://www.wim.bwl.unimuenchen.de/download/epub/mreport_2016_2.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2020).

- Hanelt, A.; Bohnsack, R.; Marz, D.; Marante, A.C. A systematic review of the literature on digital transformation: Insights and implications for strategy and organizational change. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 58, 1159–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Dong, J.Q.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupilas, K.J.; Montequin, V.R.; González, J.G.; Iglesias, G.A. Digital maturity model for research and development organization with the aspect of sustainability. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 219, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichert, R. Digital transformation maturity: A systematic review of literature. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2019, 67, 1673–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remane, G.; Hanelt, A.; Wiesboeck, F.; Kolbe, L. Digital Maturity in Traditional Industries-An Exploratory Analysis. In Proceedings of the 25th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Guimarães, Portugal, 14–17 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, R. Research on enterprise digital maturity model. Manag. Rev. 2021, 33, 152–162. [Google Scholar]

- Westerman, G.; Calméjane, C.; Bonnet, D.; Ferraris, P.; McAfee, A. Digital Transformation: A Roadmap for Billion-Dollar Organizations. 2011. Available online: https://www.capgemini.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Digital_Transformation__A_Road-Map_for_Billion-Dollar_Organizations.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Friedrich, R.; Gröne, F.; Koster, A.; Le Merle, M. Measuring Industry Digitization: Leaders and Laggards in the Digital Economy. 2011. Available online: https://www.strategyand.pwc.com/gx/en/insights/2011-2014/measuring-industry-digitization-leaders-laggards.html (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- De Carolis, A.; Macchi, M.; Negri, E.; Terzi, S. A maturity model for assessing the digital readiness of manufacturing companies. In Advances in Production Management Systems. The Path to Intelligent, Collaborative and Sustainable Manufacturing; Lödding, H., Riedel, R., Thoben, K.D., Cieminski, G., von Kiritsis, D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; p. 513. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.A.; Schallmo, D.; Lang, K.; Boardman, L. Digital Maturity Models for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the International Society for Professional Innovation Management (ISPIM) Innovation Conference, Florence, Italy, 16–19 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gökalp, E.; Martinez, V. Digital transformation capability maturity model enabling the assessment of industrial manufacturers. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 132, 103522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kıyıklık, A.; Kuşakcı, A.O.; Mbowe, B. A digital transformation maturity model for the airline industry with a self-assessment tool. Decis. Anal. J. 2022, 3, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stich, V.; Zeller, V.; Hicking, J.; Kraut, A. Measures for a successful digital transformation of SMEs. Procedia CIRP 2020, 93, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navío-Marco, J.; Ruiz-Gómez, L.M.; Sevilla-Sevilla, C. Progress in information technology and tourism management: 30 years on and 20 years after the internet—Revisiting Buhalis & Law’s landmark study about eHospitality. Tourism Manag. 2018, 69, 460–470. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Harwood, T.; Bogicevic, V.; Viglia, G.; Beldona, S.; Hofacker, C. Technological disruptions in services: Lessons from tourism and hospitality. J. Serv. Manag. 2019, 30, 484–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, I.M.; Ross, J.W.; Beath, C.; Mocker, M.; Moloney, K.G.; Fonstad, N.O. How big old companies navigate digital transformation. MIS Q. Exec. 2017, 16, 197–213. [Google Scholar]

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busulwa, R.; Pickering, M.; Mao, I. Digital transformation and hospitality management competencies: Toward an integrative framework. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 102, 103132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Leung, R. Smart hospitality-Interconnectivity and interoperability towards an ecosystem. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eller, R.; Alford, P.; Kallmünzer, A.; Peters, M. Antecedents, consequences, and challenges of Small and micro-sized enterprise digitalization in hospitality industry. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G. Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis: Emergence vs. Forcing; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1992; pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rapley, T. Doing Conversation, Discourse and Document Analysis; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.S.; Tsai, C.T. Culinary hospitality strategic development: An Asia-Pacific perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 14, 40–55. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qual. Soc. Work 2002, 1, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Research; Sage: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, B.H.; Benbasat, I. Measuring the Linkage Between Business and Information Technology Objectives. MIS Q. 1996, 20, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, A.J.G. Business & IT Alignment in Theory and Practice. In Proceedings of the 40th Hawaii International International Conference on Systems Science (HICSS-40 2007), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yeow, A.; Soh, C.; Hansen, R. Aligning with new digital strategy: A dynamic capabilities approach. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2017, 27, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, T.; Windsperger, J. Seeing through the network: Competitive advantage in the digital economy. J. Organ. Des. 2017, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Papastathopoulos, A. Organizational readiness for digital financial innovation and financial resilience. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 243, 108326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahre, C.; Hoffmann, D.; Ahlemann, F. Beyond Business-IT Alignment—Digital Business Strategies as a Paradigmatic Shift: A Review and Research Agenda. In Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral, A.; Peças, P. A framework for assessing manufacturing SMEs Industry 4.0 maturity. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubricki, K. Introducing the Six Dimensions of Digital Maturity, aka the Strategy Digital Maturity Model? 2012. Available online: https://www.onlineauthority.com/blog/introducing-dstrategy-digital-maturity-model (accessed on 20 June 2020).

| Author(s) | Key Dimensions | Maturity Levels | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| [23] | Digital intensity; digital transformation management intensity | Beginners, conservatives, fashionistas, and digirati | |

| [24] | Input, processing, output, and underlying infrastructure | Industry-level digitization index | |

| [14] | Customer experience, product innovation, strategy, organization, process digitization, collaboration, IT, culture and expertise, and transformation management | Five stages | |

| [21] | DT impact, DT readiness | Traditional industries | |

| [25] | Process, monitoring and control, technology, and organization | Manufacturing companies | |

| [26] | Strategy, products/services, technology, people/culture, management, and processes | Small- and medium-sized enterprises (SME) | |

| [22] | Digital readiness (strategy and organization, infrastructure), DT intensity (business processes and management digitalization, integrated business) | Five levels | |

| [27] | Organization, strategy, management, data analytics, data management, technology management, and support | Manufacturing | |

| [28] | Organization and technology, digital ecosystem, data and metrics, competition, and marketing | Five phases | Airline industry |

| [6] | Strategy, market, operations, culture, and technology | Three levels | Retail industry |

| [19] | Smart operations, smart products and services, smart facilities, people, strategy and organization, and sustainability | Sustainable organizations |

| Main Category | Sub-Categories | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Strategy and organization | Digital literacy of leadership | Awareness of DT |

| Knowledge and skills in digital technology | ||

| Employees’ digital skills | Knowledge and skills in digital technology | |

| Strategic alignment | Business digital strategic alignment | |

| Digital technology | Hospitality property management system (PMS) | Software-as-a-service (SaaS) solution |

| Online booking platform | Online booking platforms | |

| Social media and content platform | Social media | |

| Short video platforms | ||

| Online community platforms | ||

| Influencer community platforms | ||

| Proprietary digital channels | Official websites | |

| Mobile applications/lightweight applications | ||

| Smart facilities | Smart locks | |

| Smart home devices | ||

| Artificial intelligence drawing technology | ||

| Digital capabilities | Informationization capability | Informationization capability |

| Digital platform use | Platform order management capability | |

| Platform rule adaptation capability | ||

| Platform marketing capability | ||

| Digital networking | Digital partner selection capability | |

| Digital network integration and utilization capability | ||

| Integrated business | Digital business management | Reservation management |

| Room inventory management | ||

| Financial management | ||

| Data analysis | ||

| Digital marketing | Booking platform-based marketing | |

| Content-based marketing | ||

| Brand marketing | ||

| Digital customer relationship management | Customer feedback management | |

| Own traffic community management | ||

| Digital recruitment and training | Emerging media-based recruitment | |

| Online learning and training |

| Phase | Digital Technology | Capability | Operations | Aims |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IT-enabled transformation | Hotel PMS Smart locks | Informationization capability | Digital business management | Simplify business processes and improve efficiency |

| E-commerce-oriented DT | (above) + online booking platform; social media | (above) + platform order management; platform rule adaptation; platform marketing | (above) + booking platform marketing; customer feedback management; online learning and training; own traffic community management | (above) + platform-based market penetration |

| Content- oriented DT | (above) + content platform; smart home devices | (above) + platform marketing (content creation and traffic management) | (above) + content-based marketing; emerging media-based recruitment | (above) + channel diversification and improved dissemination |

| Brand- oriented DT | (above) + proprietary digital channels | (above) + digital partner selection; digital network integration and use | (above) + brand marketing | (above) + channel diversification and improved dissemination |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ka, X.; Ying, T.; Tang, J. A Conceptual Model for Developing Digital Maturity in Hospitality Micro and Small Enterprises. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 1511-1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer18030076

Ka X, Ying T, Tang J. A Conceptual Model for Developing Digital Maturity in Hospitality Micro and Small Enterprises. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2023; 18(3):1511-1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer18030076

Chicago/Turabian StyleKa, Xiyan, Tianyu Ying, and Jingyi Tang. 2023. "A Conceptual Model for Developing Digital Maturity in Hospitality Micro and Small Enterprises" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 18, no. 3: 1511-1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer18030076

APA StyleKa, X., Ying, T., & Tang, J. (2023). A Conceptual Model for Developing Digital Maturity in Hospitality Micro and Small Enterprises. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 18(3), 1511-1528. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer18030076