Internet Celebrities’ Impact on Luxury Fashion Impulse Buying

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is a suitable conceptual model that provides an accurate picture highlighting the main aspects of IC endorsement?

- What are the main factors of IC endorsement that affect consumers’ impulse buying?

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Internet Celebrity and Impulse Buying

2.2. IC Endorsement and Persuasion

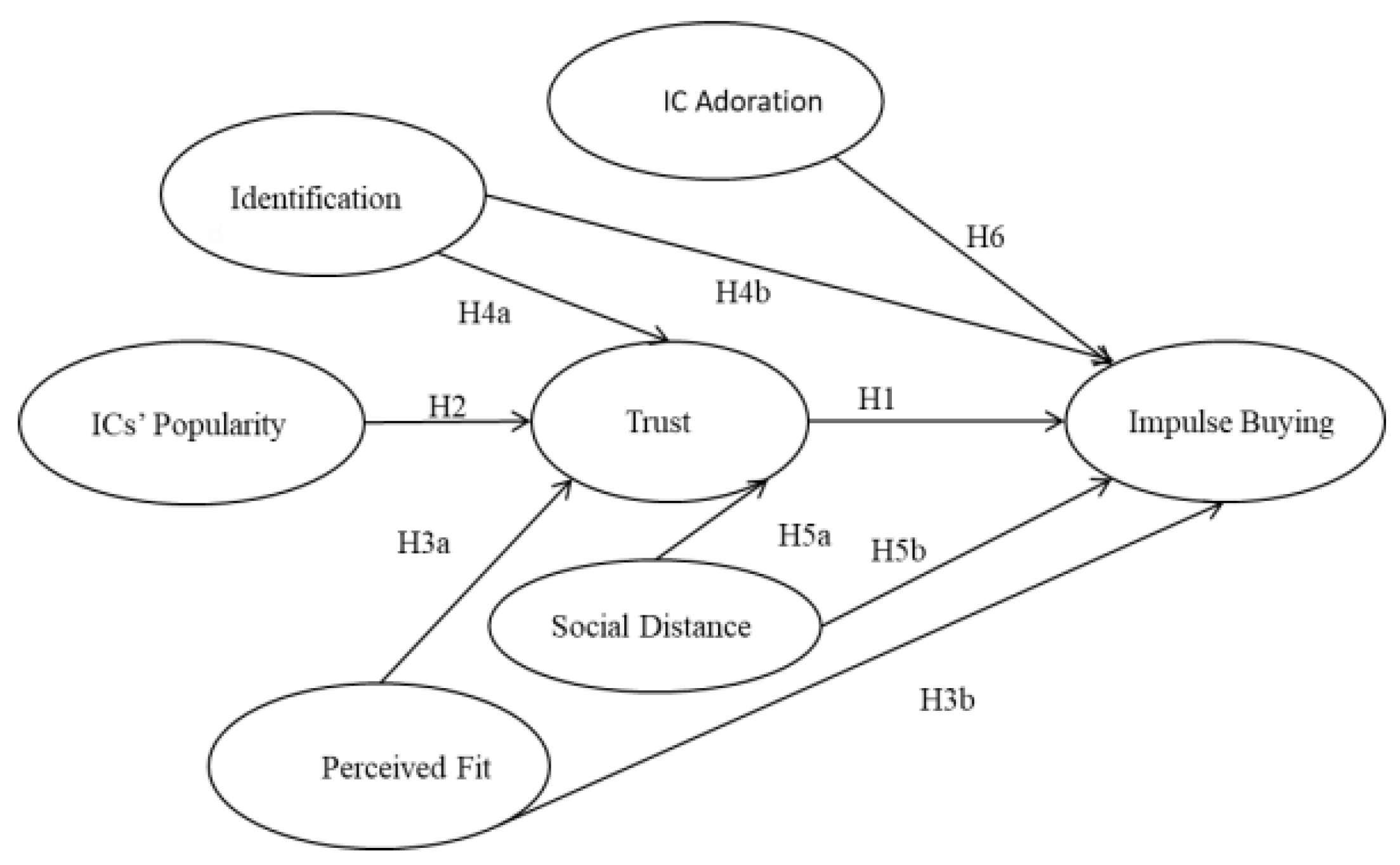

3. Hypotheses Development and Research Model

3.1. Impulse Buying

3.2. Trust

3.3. ICs’ Popularity

3.4. Perceived Fit

3.5. Identification

3.6. Social Distance

3.7. IC Adoration

3.8. Proposed Theoretical Model

4. Method

4.1. Measures

4.2. Participants and Procedure

4.3. Statistical Technique

5. Results

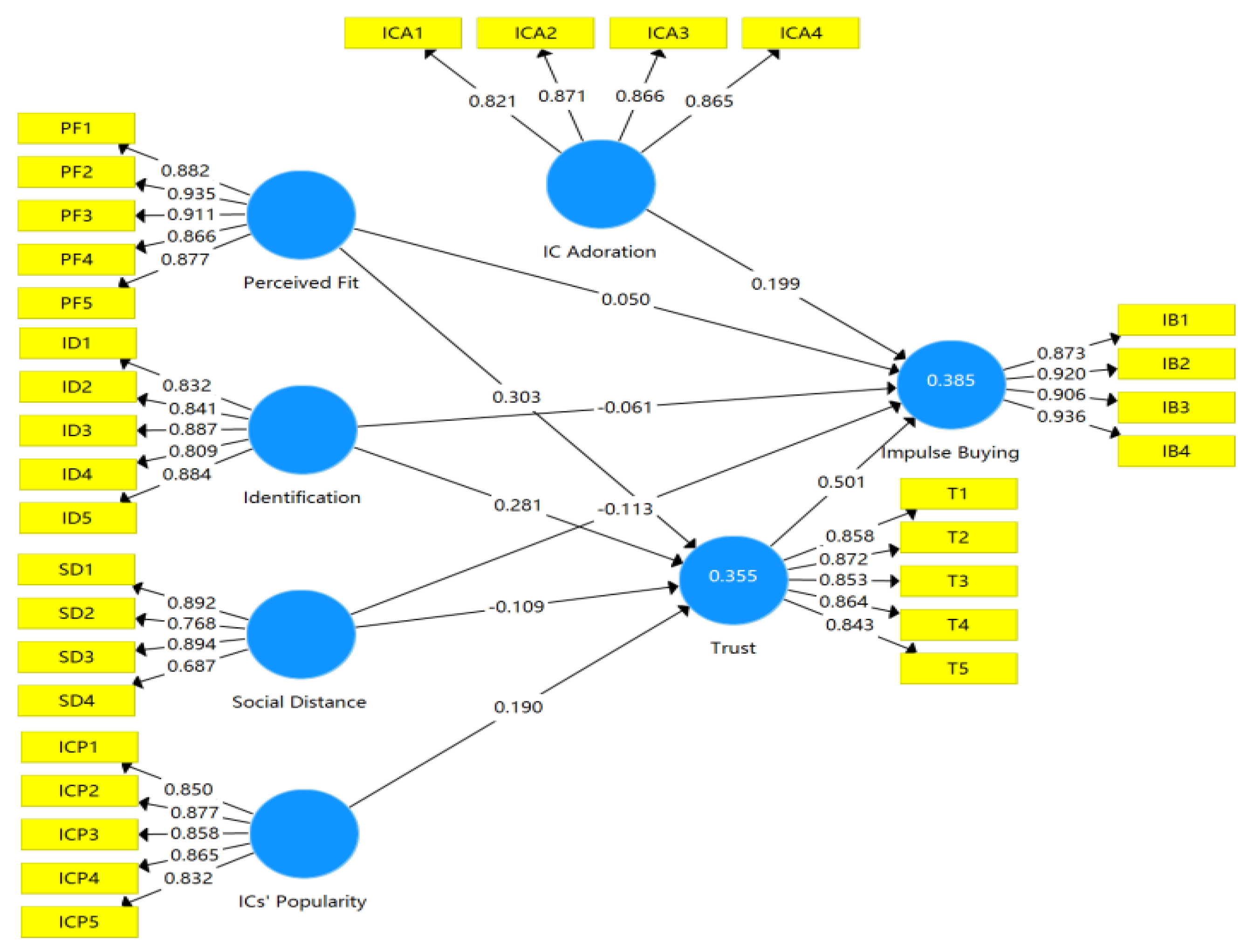

5.1. Measurement Model Assessment

5.2. Structural Model Assessment and Hypotheses Testing

5.3. Mediation Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Managerial Implications

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brandão, A.; Pinho, E.; Rodrigues, P. Antecedents and Consequences of Luxury Brand Engagement in Social Media. Span. J. Mark.–ESIC 2019, 23, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-C.; Bruning, P.F.; Swarna, H. Using Online Opinion Leaders to Promote the Hedonic and Utilitarian Value of Products and Services. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.L.; Lin, J.C.C.; Chiang, H. Sen. The Effects of Blogger Recommendations on Customers’ Online Shopping Intentions. Internet Res. 2013, 23, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A.U.; Qiu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Shahzad, M. The Impact of Social Media Celebrities’ Posts and Contextual Interactions on Impulse Buying in Social Commerce. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 115, 106178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, T.; Van Dolen, W. The Influence of Online Store Beliefs on Consumer Online Impulse Buying: A Model and Empirical Application. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, D.W. The Buying Impulse. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.J.; Kim, E.Y.; Funches, V.M.; Foxx, W. Apparel Product Attributes, Web Browsing, and e-Impulse Buying on Shopping Websites. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, P.; Augusto, M.; Matos, M. Antecedents and Outcomes of Digital Influencer Endorsement: An Exploratory Study. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer Marketing: How Message Value and Credibility Affect Consumer Trust of Branded Content on Social Media. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuarrie, E.F.; Miller, J.; Phillips, B.J. The Megaphone Effect: Taste and Audience in Fashion Blogging. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 136–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerman, S.C. The Effects of the Standardized Instagram Disclosure for Micro- and Meso-Influencers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 103, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapitan, S.; Silvera, D.H. From Digital Media Influencers to Celebrity Endorsers: Attributions Drive Endorser Effectiveness. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafesse, W.; Wood, B.P. Followers’ Engagement with Instagram Influencers: The Role of Influencers’ Content and Engagement Strategy. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Zhang, Q. Influence of Parasocial Relationship between Digital Celebrities and Their Followers on Followers’ Purchase and Electronic Word-of-Mouth Intentions, and Persuasion Knowledge. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 87, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, A.P.; Janssen, L.; Verspaget, M. Celebrity vs. Influencer Endorsements in Advertising: The Role of Identification, Credibility, and Product-Endorser Fit. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, D.; Duraipandian, I.; Sethi, D. Celebrity Endorsement: How Celebrity–Brand–User Personality Congruence Affects Brand Attitude and Purchase Intention. J. Mark. Commun. 2014, 89, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergkvist, L.; Zhou, K.Q. Celebrity Endorsements: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Advert. 2016, 35, 642–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.T. Flow and Social Capital Theory in Online Impulse Buying. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2277–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Hu, F. Website Attributes in Urging Online Impulse Purchase: An Empirical Investigation on Consumer Perceptions. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 55, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Heng, X.; Sahu, V. Impact of Store Size on Impulse Purchase. J. Mark. 2009, 8, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.-J.; Eckman, M.; Yan, R.-N. Application of the Stimulus-Organism-Response Model to the Retail Environment: The Role of Hedonic Motivation in Impulse Buying Behavior. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2011, 21, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, Y.; Niu, H.J. The Effects of Idolatry and Personality Traits on Impulse Buying: An Empirical Study. Int. J. Manag. 2008, 25, 633–641. [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez, D.; Wu, X.; Nguyen, B.; Kent, A.; Gutierrez, A.; Chen, T. Investigating Narrative Involvement, Parasocial Interactions, and Impulse Buying Behaviours within a Second Screen Social Commerce Context. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 53, 102135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejavibulya, P.; Eiamkanchanalai, S. The Impacts of Opinion Leaders towards Purchase Decision Engineering under Different Types of Product Involvement. Syst. Eng. Procedia 2011, 2, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Martensen, A.; Brockenhuus-Schack, S.; Zahid, A.L. How Citizen Influencers Persuade Their Followers. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. An Int. J. 2018, 22, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, C.W.; Kim, Y.K. The Mechanism by Which Social Media Influencers Persuade Consumers: The Role of Consumers’ Desire to Mimic. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 905–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.; Swaminathan, V.; Brooks, G. Driving Brand Engagement Through Online Social Influencers: An Empirical Investigation of Sponsored Blogging Campaigns. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Cho, H. Fostering Parasocial Relationships with Celebrities on Social Media: Implications for Celebrity Endorsement. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and Consequences of Opinion Leadership. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufaris, M. Applying the Technology Acceptance Model and Flow Theory to Online Consumer Behavior. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Chen, C.W. Impulse Buying Behaviors in Live Streaming Commerce Based on the Stimulus-Organism-Response Framework. Information 2021, 12, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.I.; Irving, L.; Harold, H. Communication and Persuasion; Psychological Studies of Opinion Change; Yale University Press: New Haven, NH, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis, H.C. Attitudes and Attitude Change; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Pornpitakpan, C. The Persuasiveness of Source Credibility: A Critical Review of Five Decades’ Evidence. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 243–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, C. Visibility Labour: Engaging with Influencers’ Fashion Brands and #OOTD Advertorial Campaigns on Instagram. Media Int. Aust. 2016, 161, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, H.; Beattie, J.; Friese, S. Objects, Decision Considerations and Self-Image in Men’s and Women’s Impulse Purchases. Acta Psychol. (Amst.) 1996, 93, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, S.; Xu, Y.; Thomas, J. Luxury Fashion Consumption and Generation Y Consumers. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2015, 19, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, S.; Ang, L.; Welling, R. Self-Branding, ‘Micro-Celebrity’ and the Rise of Social Media Influencers. Celebr. Stud. 2017, 8, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.R.; Troshani, I.; Chandrasekar, D. Signalling Effects of Vlogger Popularity on Online Consumers. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2020, 60, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P. Drivers of New Product Recommending and Referral Behaviour on Social Network Sites. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 535–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Kim, H.Y. Influencer Advertising on Social Media: The Multiple Inference Model on Influencer-Product Congruence and Sponsorship Disclosure. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 2018, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Veirman, M.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. Marketing through Instagram Influencers: The Impact of Number of Followers and Product Divergence on Brand Attitude. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 798–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräve, J.-F. Exploring the Perception of Influencers Vs. Traditional Celebrities. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Social Media & Society-#SMSociety17, Toronto, ON, Canada, 28–30 July 2017; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA; Volume 28, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N.J.; Phua, J.; Lim, J.; Jun, H. Disclosing Instagram Influencer Advertising: The Effects of Disclosure Language on Advertising Recognition, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intent. J. Interact. Advert. 2017, 17, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergkvist, L.; Hjalmarson, H.; Mägi, A.W. A New Model of How Celebrity Endorsements Work: Attitude toward the Endorsement as a Mediator of Celebrity Source and Endorsement Effects. Int. J. Advert. 2016, 35, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, H. The Significance of Impulse Buying Today. J. Mark. 1962, 26, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.L.; Chen, K.W.; Chiu, M.L. Defining Key Drivers of Online Impulse PurchasingS: A Perspective of Both Impulse Shoppers and System Users. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X. How Does Shopping with Others Influence Impulsive Purchasing? J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.; Prendergast, G.P. Social Comparison, Imitation of Celebrity Models and Materialism among Chinese Youth. Int. J. Advert. 2008, 27, 799–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Z.K.; Barnes, S.J.; Zhao, S.J.; Zhang, H. Can Consumers Be Persuaded on Brand Microblogs? An Empirical Study. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Tukachinsky, R.H. Narrative Persuasion 2.0: Transportation in Participatory Websites. Commun. Res. Rep. 2017, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, G. Who Is the Celebrity Endorser? Cultural Foundations of the Endorsement Process. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamins, M.A. An Investigation into the “Match-up” Hypothesis in Celebrity Advertising: When Beauty May Be Only Skin Deep. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, K. Celebrity Endorsements: Influence of a Product-Endorser Match on Millennials Attitudes and Purchase Intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 32, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Till, B.D.; Busler, M. The Match-Up Hypothesis: Physical Attractiveness, Expertise, and the Role of Fit on Brand Attitude, Purchase Intent and Brand Beliefs. J. Advert. 2000, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E.; Bettman, J.R. Connecting With Celebrities: How Consumers Appropriate Celebrity Meanings for a Sense of Belonging. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Trope, Y.; Liberman, N.; Levinsagi, M. Construal Levels and Self-Control. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gefen, D.; Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W. Trust and TAM in Online Shopping: An Integrated Model. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabner-Kräuter, S.; Kaluscha, E.A. Empirical Research in On-Line Trust: A Review and Critical Assessment. Int. J. Hum.Comput. Stud. 2003, 58, 783–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.H.; Nicholson, M. A Multidisciplinary Cognitive Behavioural Framework of Impulse Buying: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B.; Pan, Z. How Do Product Recommendations Affect Impulse Buying? An Empirical Study on WeChat Social Commerce. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawron, M.; Strzelecki, A. Consumers’ Adoption and Use of e-Currencies in Virtual Markets in the Context of an Online Game. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1266–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Knoll, K.; Leidner, D.E. Is Anybody out There? Antecedents of Trust in Global Virtual Teams. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1998, 14, 29–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvily, B.; Perrone, V.; Zaheer, A. Trust as an Organizing Principle. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Sato, A. The Psychology of Impulse Buying: An Integrative Self-Regulation Approach. J. Consum. Policy 2011, 34, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.; Spence, P.R.; Gentile, C.J.; Edwards, A.; Edwards, A. How Much Klout Do You Have A Test of System Generated Cues on Source Credibility. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, A12–A16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffaker, D. Dimensions of Leadership and Social Influence in Online Communities. Hum. Commun. Res. 2010, 36, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, G.; Uray, N.; Silahtaroglu, G. How to Engage Consumers through Effective Social Media Use-Guidelines for Consumer Goods Companies from an Emerging Market. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 768–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwick, A.E. Instafame: Luxury Selfies in the Attention Economy. Public Cult. 2015, 27, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Zheng, Y. Following the Majority: Social Influence in Trusting Behavior. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Watkins, B. YouTube Vloggers’ Influence on Consumer Luxury Brand Perceptions and Intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5753–5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A. Selecting the Right Cause Partners for the Right Reasons: The Role of Importance and Fit in Cause-Brand Alliances. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 26, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, A. A Multi-Method Investigation of Consumer Motivations in Impulse Buying Behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2000, 17, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Sicilia, M.; Moyeda-Carabaza, A.A. Creating Identification with Brand Communities on Twitter: The Balance between Need for Affiliation and Need for Uniqueness. Internet Res. 2017, 27, 21–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogardus, E.S. A Social Distance Scale. Sociol. Soc. Res. 1933, 22, 265–271. [Google Scholar]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-Level Theory of Psychological Distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liviatan, I.; Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Interpersonal Similarity as a Social Distance Dimension: Implications for Perception of Others’ Actions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 44, 1256–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trope, Y.; Fishbach, A. Counteractive Self-Control in Overcoming Temptation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesser, A. Toward a Self-Evaluation Maintenance Model of Social Behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 21, 181–227. [Google Scholar]

- Steffes, E.M.; Burgee, L.E. Social Ties and Online Word of Mouth. Internet Res. 2009, 19, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Esch, P.; Arli, D.; Castner, J.; Talukdar, N.; Northey, G. Consumer Attitudes towards Bloggers and Paid Blog Advertisements: What’s New? Mark. Intell. Plan. 2018, 36, 778–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Barnes, B.R.; Talias, M.A. Exporter–Importer Relationship Quality: The Inhibiting Role of Uncertainty, Distance, and Conflict. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2006, 35, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, J.S.; Huang, C.Y.; Chuang, M.C. Antecedents of Taiwanese Adolescents’ Purchase Intention toward the Merchandise of a Celebrity: The Moderating Effect of Celebrity Adoration. J. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 145, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazon, M.; Delgado-Ballester, E.; Sicilia, M. Fostering Brand Love in Facebook Brand Pages. Online Inf. Rev. 2019, 43, 710–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Ahuvia, A.; Bagozzi, R.P. Brand Love. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Qiu, T.; Xie, Y. Scientific Construction of the Evaluation Index System for Microbloggers’ Influence. J. Zhejiang Univ. 2014, 44, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Chen, N.; Ran, X. Computational Modeling of Weibo User Influence Based on Information Interactive Network. Online Inf. Rev. 2016, 40, 867–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and Validation of a Scale to Measure Celebrity Endorsers’ Perceived Expertise, Trustworthiness, and Attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCroskey, J.C.; Richmond, V.P.; Daly, J.A. The Development of a Measure of Perceived Homophily in Interpersonal Communication. Hum. Commun. Res. 1975, 1, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Social Space and Symbolic Power. Sociol. Theory 1989, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltby, J.; Day, L.; McCutcheon, L.E.; Houran, J.; Ashe, D. Extreme Celebrity Worship, Fantasy Proneness and Dissociation: Developing the Measurement and Understanding of Celebrity Worship within a Clinical Personality Context. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, H.; Hartmann, T. The PSI-Process Scales. A New Measure to Assess the Intensity and Breadth of Parasocial Processes. Communications 2008, 33, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auter, P.J.; Palmgreen, P. Development and Validation of a Parasocial Interaction Measure: The Audience-persona Interaction Scale. Commun. Res. Rep. 2000, 17, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Benbasat, I. E-Commerce Product Recommendation Agents: Use, Characteristics, and Impact. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-Sem), 2nd ed.; Sage publications: Thousands Oak, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, Y.; McColl, R.; Kitchen, P.J. New Luxury Brand Positioning and the Emergence of Masstige Brands. J. Brand Manag. 2009, 16, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, G.A.; Yazdanparast, A.; Strutton, D. Investigating the Marketing Impact of Consumers’ Connectedness to Celebrity Endorsers. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzl, C.; Roldan, J.L.; Cepeda, G. Mediation Analysis in Partial Least Squares Path Modelling, Helping Researchers Discuss More Sophisticated Models. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1849–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.; Menon, S.; Sivakumar, K. Online Peer and Editorial Recommendations, Trust, and Choice in Virtual Markets. J. Interact. Mark. 2005, 19, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M.; Gordon, B.S.; James, J.D. Social Capital and Consumer Happiness: Toward an Alternative Explanation of Consumer-Brand Identification. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 28, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yan, X.; Fan, W.; Gordon, M. The Joint Moderating Role of Trust Propensity and Gender on Consumers’ Online Shopping Behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 43, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragoncillo, L.; Orús, C. Impulse Buying Behaviour: An Online-Offline Comparative and the Impact of Social Media. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2018, 22, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S. Exploring Relationship between Value Perception and Luxury Purchase Intention: A Case of Indian Millennials. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2019, 23, 414–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiao, F. The Symbolic Meaning of Luxury-Lite Fashion Brands among Younger Chinese Consumers. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2020, 24, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande Yamawaki, M.A.; Sarfati, G. The Millennials Luxury Brand Engagement on Social Media: A Comparative Study of Brazilians and Italians. Internext 2019, 14, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R. Effect of Celebrity Endorsements on Dimensions of Customer-Based Brand Equity: Empirical Evidence from Indian Luxury Market. J. Creat. Commun. 2016, 11, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Item | Statement | M | SD | Related Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICs’ Popularity | 1 | This IC has a lot of fans | 5.45 | 1.52 | Chen et al. (2014), Wang et al. (2015) |

| 2 | This IC enjoys great fame in society | 5.05 | 1.61 | ||

| 3 | There are many people sharing and discussing the products recommended by the IC | 4.64 | 1.61 | ||

| 4 | This IC enjoys high popularity on the Internet | 5.05 | 1.52 | ||

| 5 | This IC has highly active followers | 4.92 | 1.50 | ||

| Perceived Fit | 1 | The product recommended has something in common with the IC’s daily publish content | 3.24 | 1.71 | Till and Busler (2000)Ohanian (1990) |

| 2 | The personal style of IC is similar to the product | 3.31 | 1.72 | ||

| 3 | The lifestyle the IC represent has something in common with the product | 3.33 | 1.73 | ||

| 4 | The IC knows a lot about the product | 3.47 | 1.75 | ||

| 5 | The IC is familiar with fashion luxury | 3.45 | 1.74 | ||

| Social Distance | 1 | The perceived personality difference between me and IC | 5.13 | 1.50 | McCroskey et al. (1975) Bourdieu (1989) |

| 2 | The perceived appearance difference between me and IC | 5.22 | 1.48 | ||

| 3 | The perceived taste and style difference between me and IC | 4.90 | 1.49 | ||

| 4 | The perceived living standard difference between me and IC | 5.67 | 1.41 | ||

| IC Adoration | 1 | I often pay attention to updates of some ICs | 2.77 | 1.68 | Maltby et al. (2006) |

| 2 | I actively respond to the topics the ICs raise | 1.92 | 1.17 | ||

| 3 | Some opinions of ICs exert great impact on me | 2.09 | 1.32 | ||

| 4 | I spend plenty of time browsing ICs’ updates every day | 1.99 | 1.30 | ||

| Identification | 1 | I feel close with this IC | 4.05 | 1.80 | Schramm and Hartmann (2008)Auter and Palmgreen (2000) |

| 2 | I share similar interest with this IC | 3.54 | 1.71 | ||

| 3 | I appreciate the physical image of this IC | 4.13 | 1.83 | ||

| 4 | I yearn for the life status of this IC | 3.54 | 1.79 | ||

| 5 | I share the same value with this IC | 3.74 | 1.76 | ||

| Trust | 1 | I believe this IC has the ability to provide professional information | 3.76 | 1.71 | Xiao and Benbasat (2007) |

| 2 | I believe the IC is honest about the product and describes it objectively | 3.75 | 1.58 | ||

| 3 | I believe this IC won’t just recommend the product just for business interest | 3.62 | 1.70 | ||

| 4 | I believe this IC can provide unbiased recommendation | 3.55 | 1.55 | ||

| 5 | I believe this IC recommends for helping others | 3.90 | 1.62 | ||

| Impulse Buying | 1 | I feel the luxury product is not that expensive than I first saw it | 3.02 | 1.49 | Verhagen and Van Dolen (2011) |

| 2 | I hadn’t planned to purchase before, but I want to buy it now | 2.79 | 1.45 | ||

| 3 | Seeing so many people buying the product, I feel I want it eagerly | 2.90 | 1.55 | ||

| 4 | It’s hard to resist the temptation to do this purchase | 2.80 | 1.52 |

| Measure | Items | Frequency | Percentages (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 344 | 58.8 |

| Male | 241 | 41.2 | |

| Age | <20 | 38 | 6.5 |

| 21–30 | 438 | 74.9 | |

| 31–40 | 37 | 6.3 | |

| 41–50 | 42 | 7.2 | |

| >50 | 30 | 5.1 | |

| Education | Junior and high school | 14 | 2.4 |

| Junior college | 24 | 4.1 | |

| Undergraduate school | 251 | 42.9 | |

| Master | 209 | 35.7 | |

| Ph.D | 87 | 14.9 | |

| Monthly disposable income | <1000 | 73 | 12.5 |

| 1001–3000 | 231 | 39.5 | |

| 3001–5000 | 96 | 16.4 | |

| >5000 | 185 | 31.6 |

| Factors | Standardized Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICs’ Popularity (IP) | 0.850 | 0.910 | 0.932 | 0.734 |

| 0.877 | ||||

| 0.858 | ||||

| 0.865 | ||||

| 0.832 | ||||

| Perceived Fit (PF) | 0.882 | 0.937 | 0.952 | 0.800 |

| 0.935 | ||||

| 0.911 | ||||

| 0.866 | ||||

| 0.877 | ||||

| Identification (ID) | 0.832 | 0.905 | 0.929 | 0.724 |

| 0.841 | ||||

| 0.887 | ||||

| 0.809 | ||||

| 0.884 | ||||

| Social Distance (SD) | 0.892 | 0.844 | 0.887 | 0.664 |

| 0.768 | ||||

| 0.894 | ||||

| 0.687 | ||||

| IC Adoration (ICA) | 0.821 | 0.878 | 0.916 | 0.733 |

| 0.871 | ||||

| 0.866 | ||||

| 0.865 | ||||

| Trust (T) | 0.858 | 0.911 | 0.933 | 0.736 |

| 0.872 | ||||

| 0.853 | ||||

| 0.864 | ||||

| 0.843 | ||||

| Impulse Buying (IB) | 0.873 | 0.930 | 0.950 | 0.826 |

| 0.92 | ||||

| 0.906 | ||||

| 0.936 |

| Hypotheses | Hypothesized Association | Path Coefficients | Collinearity Assessment | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesized Relationships | VIF | ||||

| H1 | T-IB | 0.501 *** | 1.488 | 12.61 | 0.000 |

| H2 | IP-T | 0.190 *** | 1.270 | 4.37 | 0.000 |

| H3a | PF-T | 0.303 *** | 1.121 | 7.20 | 0.000 |

| H3b | PF-IB | 0.050 | 1.342 | 1.15 | 0.250 |

| H4a | ID-T | 0.281 *** | 1.411 | 6.10 | 0.000 |

| H4b | ID-IB | −0.061 | 1.497 | 1.31 | 0.190 |

| H5a | SD-T | −0.109 *** | 1.167 | 2.81 | 0.000 |

| H5b | SD-IB | −0.113 *** | 1.099 | 3.25 | 0.000 |

| H6 | ICA-IB | 0.199 *** | 1.300 | 5.40 | 0.000 |

| R2 | Q2 | |

|---|---|---|

| T | 0.355 | 0.259 |

| IB | 0.385 | 0.318 |

| Direct Standardized Coefficient | 95% Confidence Interval of the Direct Effect | Significance (p < 0.05)? | Indirect Standardized Coefficient | 95% Confidence Interval of the Indirect effect | Significance (p < 0.05)? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID→IB | −0.060 | (−0.148, 0.028) | No | 0.145 | (0.098, 0.195) | Yes |

| IP→IB | −0.032 | (−0.102, 0.042) | No | 0.095 | (0.049, 0.149) | Yes |

| SD→IB | −0.114 | (−0.178, −0.043) | Yes | −0.054 | (−0.094, −0.015) | Yes |

| PF→IB | 0.050 | (−0.039, 0.129) | No | 0.150 | (0.110, 0.200) | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, M.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. Internet Celebrities’ Impact on Luxury Fashion Impulse Buying. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2470-2489. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16060136

Chen M, Xie Z, Zhang J, Li Y. Internet Celebrities’ Impact on Luxury Fashion Impulse Buying. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2021; 16(6):2470-2489. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16060136

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Mingliang, Zhaohan Xie, Jing Zhang, and Yingying Li. 2021. "Internet Celebrities’ Impact on Luxury Fashion Impulse Buying" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 16, no. 6: 2470-2489. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16060136

APA StyleChen, M., Xie, Z., Zhang, J., & Li, Y. (2021). Internet Celebrities’ Impact on Luxury Fashion Impulse Buying. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 16(6), 2470-2489. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16060136