Machine Learning-Assisted Polymer and Polymer Composite Design for Additive Manufacturing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Additive Manufacturing of Polymers and Polymer Composites

2.1. AM Techniques for Polymers and Polymer Composites

2.1.1. Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM)

2.1.2. Stereolithography (SLA) and Digital Light Processing (DLP)

2.1.3. Binder Jetting

2.1.4. Selective Laser Sintering (SLS)

2.1.5. Material Jetting

2.2. Polymer Composite Materials in AM

| Property | Thermoplastics | Thermosets | Elastomers | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal behavior | Reversibly soften and harden with heat | Irreversibly cured via crosslinking | Remain elastic across a wide temperature range | [42,90,109] |

| Reprocessability | Can be reheated and reshaped; recyclable | Cannot be reshaped once cured | Limited and material-dependent | [90,104,109] |

| Mechanical properties | Moderate strength; prone to warping and shrinkage | High stiffness and precision, but brittle | Stretchable and impact-absorbing | [42,90,109] |

| Surface quality | May need postprocessing to remove layer artifacts | Naturally smooth finish with high dimensional accuracy | Finish varies by technique; can be rough without tuning | [90,107,109] |

| Common AM techniques | FDM, SLS | SLA, DLP | Material Jetting, modified FDM | [101,102,103] |

| Main limitations | Warping, anisotropy, shrinkage | Brittleness, short shelf life, requires post-curing | Viscosity control challenges; weak interlayer bonding | [90,104,109] |

2.2.1. Reinforcing Materials in Polymer Composite AM

2.2.2. Functional Fillers in Polymer Composite AM

2.2.3. Factors Affecting Material Properties in AM

2.2.4. Industrial Applications of Polymer AM Composites

3. ML for Material Property Prediction in Additive Manufacturing

3.1. Overview of Data-Driven vs. Physics-Based Modeling

3.2. Data Sources for ML Models

3.3. ML Approaches Used in Property Prediction

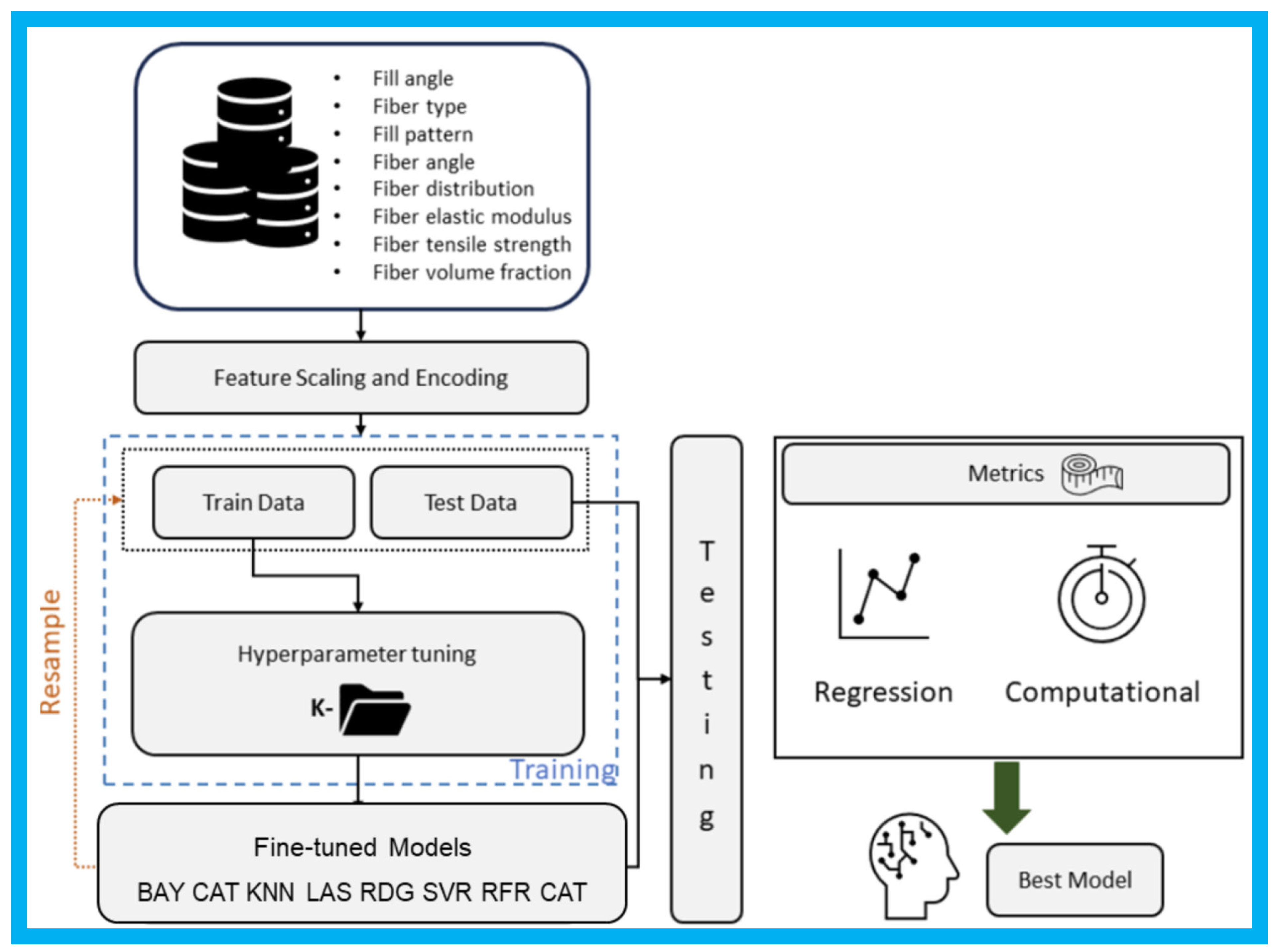

3.3.1. Supervised Learning Models

3.3.2. Unsupervised Learning

| Model Type | Common Algorithms | Applications in AM | Key Strengths | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Regression | Linear Regression (LR), Ridge, SVR | Predicting tensile strength, modulus, thermal conductivity | Simple, interpretable; SVR handles nonlinearity with kernel functions | [199,200,201,202,222,223] |

| Ensemble Methods | Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, XGBoost, AdaBoost | Estimating tensile strength, capturing interactions in mixed feature sets (e.g., print speed, filler type) | High accuracy; robust to noise; captures complex feature interactions | [203,204,205,206,215] |

| Neural Networks | Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) | Predicting bonding strength, toughness, conductivity; uses print data, porosity, fiber alignment | Excellent with high-dimensional, image-rich, or complex data; learns nonlinearities | [207,208,209,223] |

3.3.3. Semi-Supervised Learning

3.3.4. Self-Supervised Learning

3.3.5. Reinforcement Learning

3.3.6. Hybrid AI Models Combining ML with Physics-Based Approaches

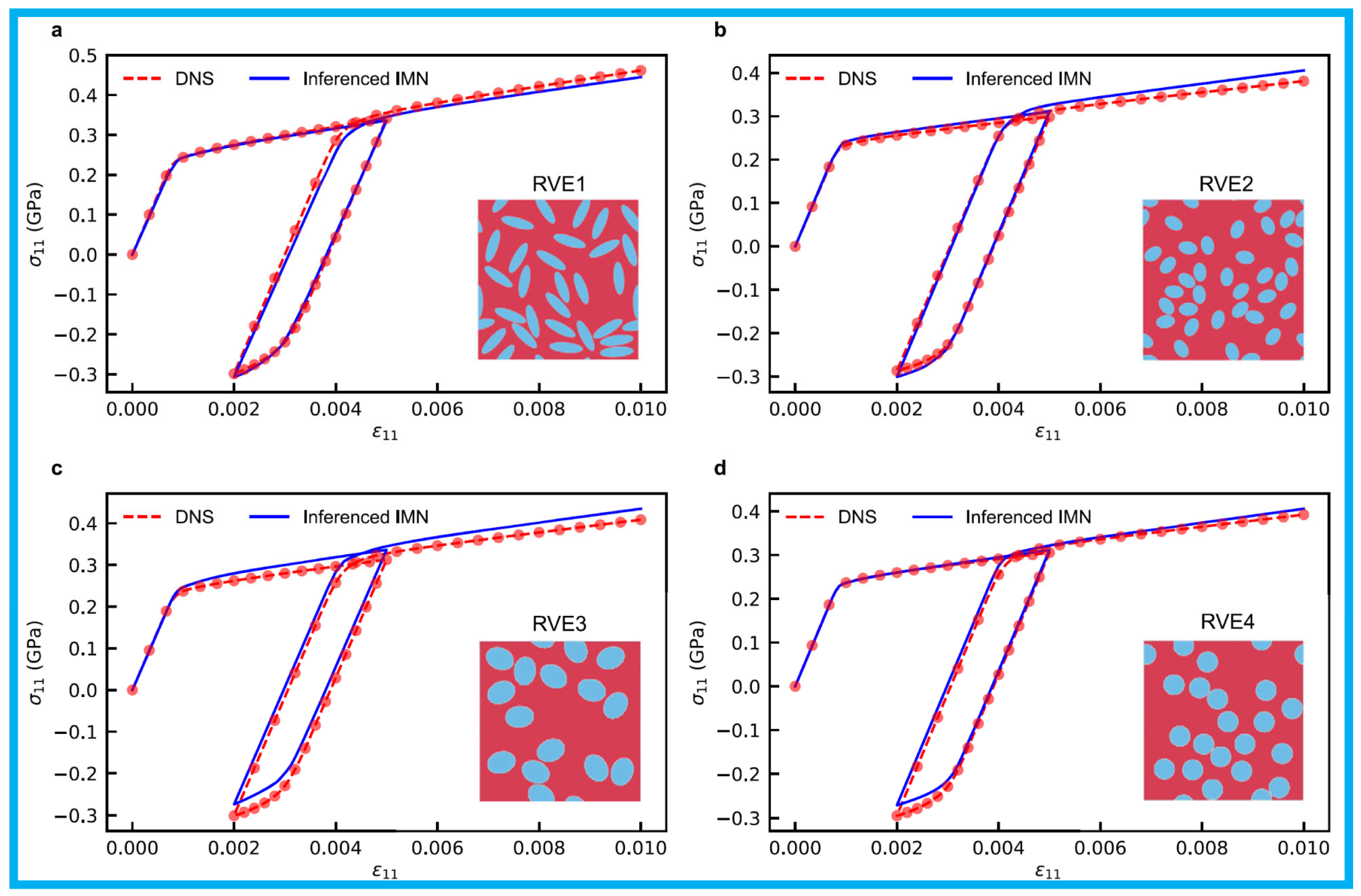

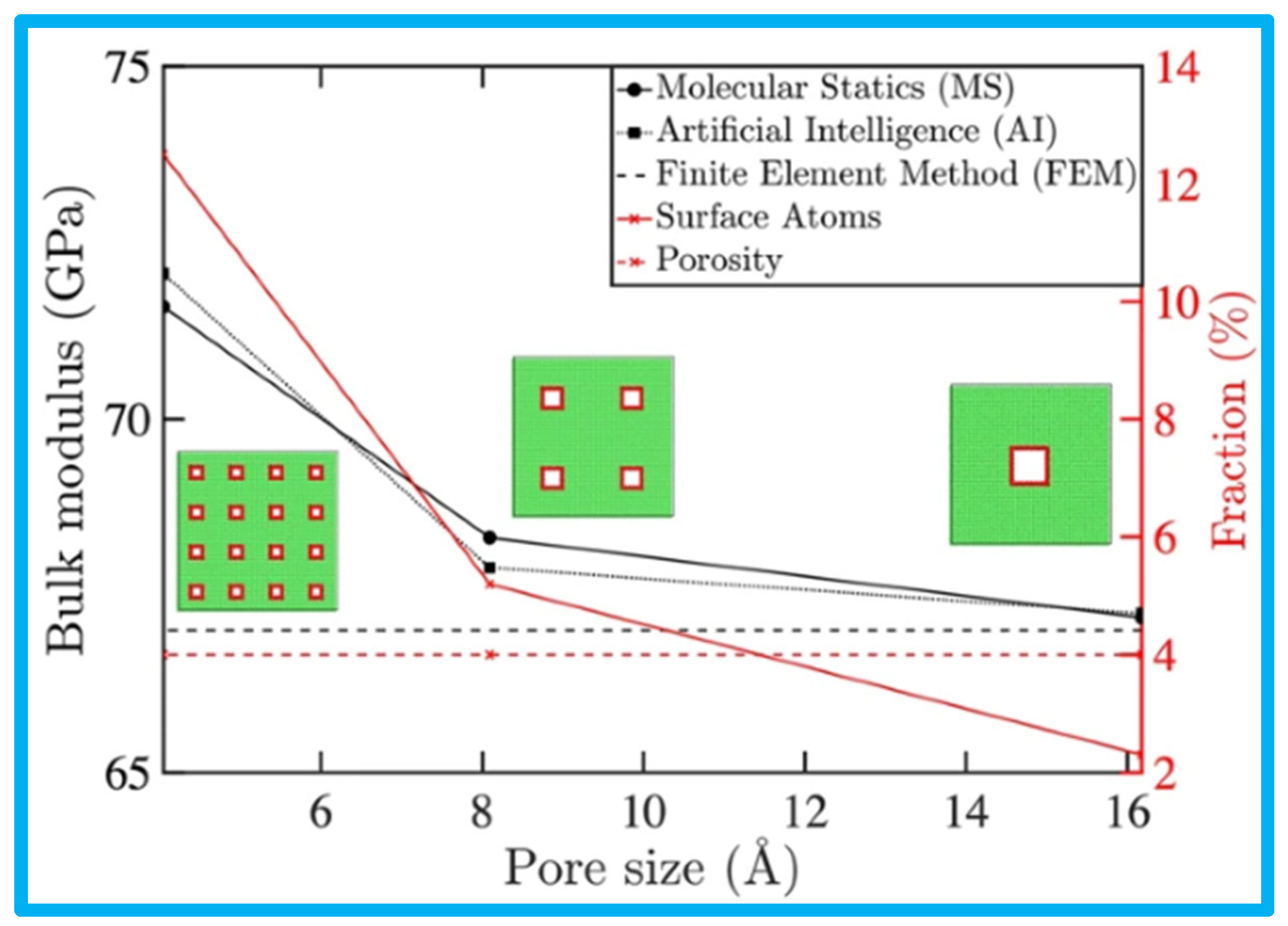

4. Advances in ML-Driven Property Prediction

4.1. Mechanical Property Prediction

4.2. Thermal and Electrical Property Prediction

4.3. Process–Property Relationship Prediction

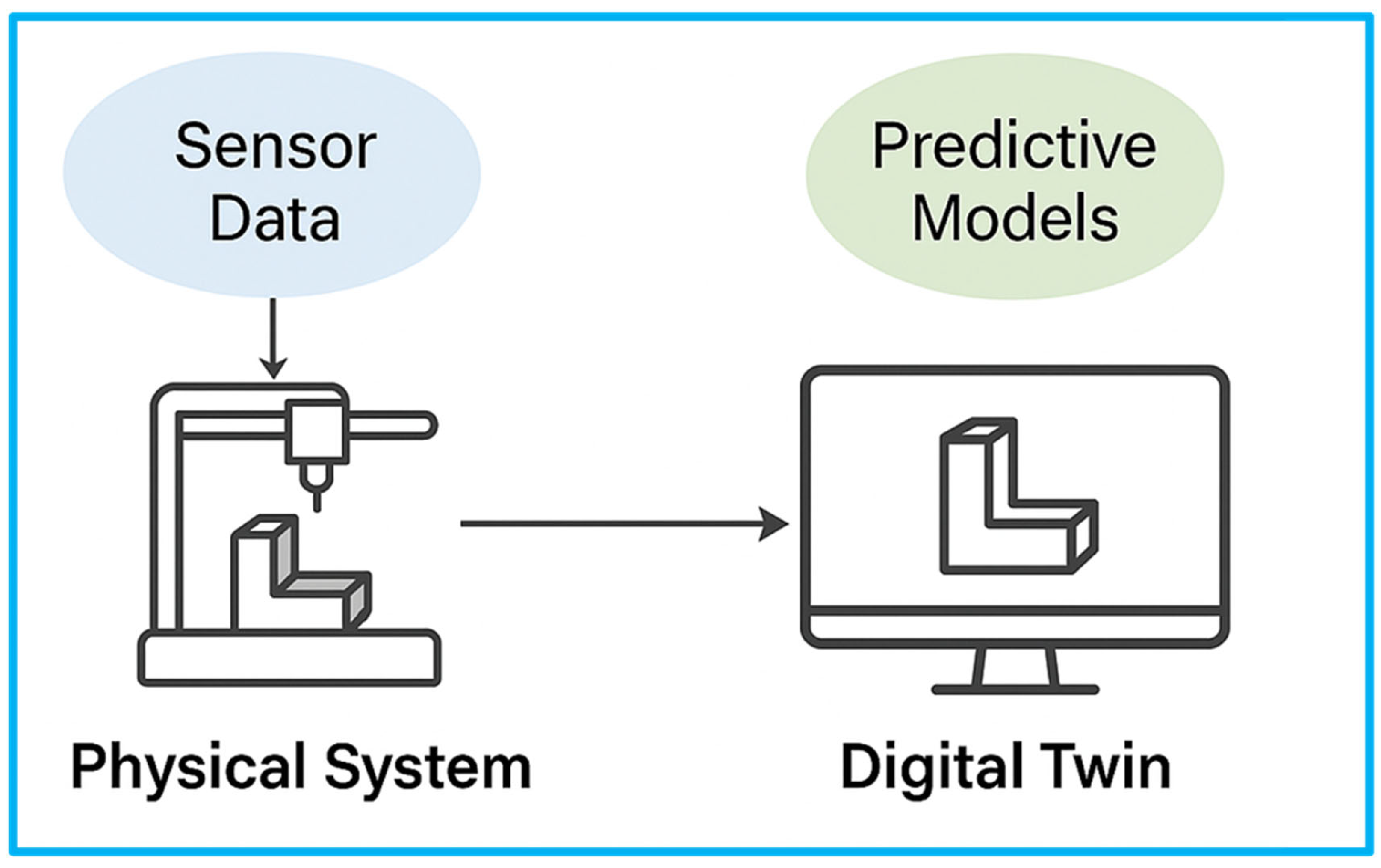

4.4. ML-Based Digital Twins for AM Quality Control

4.5. Characterization Tools in ML-Enhanced Additive Manufacturing Research

5. Challenges in ML-Based Material Property Prediction

5.1. Data Availability and Quality Issues

5.2. Model Generalization and Transferability

5.3. Computational Cost and Scalability

5.4. Explainability and Trust in ML Models

5.5. Industrial Integration and Standardization

6. Future Directions and Emerging Trends

6.1. ML-Based Autonomous Manufacturing

6.1.1. Self-Learning ML Models for Real-Time Process Adaptation

6.1.2. ML-Enhanced Robotics for Automated AM Production

6.2. Generative ML for Material Design

6.3. ML-Based Inverse Design Approaches

6.4. ML for Multiscale Property Prediction

6.5. ML in Sustainable and Smart Manufacturing

7. Conclusions

7.1. Key Findings

- Diverse AM Techniques and Material Systems: We detailed the major AM modalities, Fused Deposition Modeling, Stereolithography, Selective Laser Sintering, material and binder jetting, and emerging directed-energy and multi-material methods and their compatibility with thermoplastics, thermosets, elastomers, and a spectrum of fiber, nanoparticle, and functional fillers. Each technique offers unique advantages such as resolution, mechanical strength, and multifunctionality, but also introduces process-induced variability in layer adhesion, porosity, and anisotropy that complicates property prediction.

- ML Paradigms and Applications: ML approaches from classical regression and tree-based ensemble methods to deep neural networks, clustering, and reinforcement learning have been successfully deployed to predict mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties, optimize process parameters, detect defects in real time, and even steer generative and inverse design of novel composites. Self- and semi-supervised learning, as well as hybrid physics-informed models, have emerged to overcome data scarcity and embed fundamental physical laws into data-driven workflows.

- Explainability, Industrial Integration, and Sustainability: Explainable ML techniques, including SHAP, LIME, PDP, attention mechanisms, and formal concept lattices, are mitigating “black box” concerns, fostering trust in safety-critical applications. Yet industrial deployment still lags, impeded by proprietary data silos, a lack of standardized ML protocols, and the gap between lab-scale datasets and real-world variability. Simultaneously, ML is enabling more sustainable AM practices, the design of bio-based composites, self-healing polymers, ML-assisted life-cycle assessment, and closed-loop recycling strategies that reduce waste and energy consumption.

7.2. Future Outlook

- Federated and Privacy-Preserving Learning: Developing federated ML frameworks will allow multiple stakeholders to train shared models on confidential industrial datasets without exposing proprietary information, broadening the data landscape while safeguarding intellectual property (IP).

- Standardization and Open Data Ecosystems: Establishing AI-integrated standards through ASTM, ISO, and industry consortia, coupled with curated, open-source AM datasets, will enable robust benchmarking, reproducibility, and accelerated model validation across laboratories and production sites.

- Autonomous and Digital-Twin Manufacturing: The integration of ML-powered digital twins, closed-loop control, and multi-agent reinforcement learning will move AM toward self-optimizing “lights-out” factories, where real-time sensor fusion and AI decision-making assure quality and adaptability at scale.

- Next-Generation ML-Based Design: Advances in generative models (GANs, VAEs) and inverse-design algorithms promise to unlock unprecedented composite architectures and functionally graded materials, tailoring microstructure and composition to application-specific performance targets with minimal human intervention.

- Sustainability by Design: Continued growth in ML-enabled life-cycle assessment, eco-design of polymer matrices and fillers, and process optimization for energy efficiency will be essential to align AM with circular economy principles and global decarbonization goals.

- Keep Pace with AM: AM is evolving quickly. ML must keep pace with the new developments in AM. In polymer and polymer composite AM, new developments such as volumetric 3D printing [374] and polymer curing by various electromagnetic waves (for example, visible light) and mechanical waves (for example, ultrasound) [375] deserve attention.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gu, D.; Shi, X.; Poprawe, R.; Bourell, D.L.; Setchi, R.; Zhu, J. Material-structure-performance integrated laser-metal additive manufacturing. Science 2021, 372, eabg1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Ma, Y.; Rosen, D.W. Intelligent additive manufacturing and design: State of the art and future perspectives. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 59, 103139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Trofimov, V.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Feng, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, J.; Wang, D. Study on additive and subtractive manufacturing of high-quality surface parts enabled by picosecond laser. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 318, 118013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBoer, B.; Nguyen, N.; Diba, F.; Hosseini, A. Additive, subtractive, and formative manufacturing of metal components: A life cycle assessment comparison. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 115, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moehring, H.-C.; Maucher, C.; Becker, D.; Stehle, T.; Eisseler, R. The additive-subtractive process chain–A review. J. Mach. Eng. 2023, 23, 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathish, K.; Kumar, S.S.; Magal, R.T.; Selvaraj, V.; Narasimharaj, V.; Karthikeyan, R.; Sabarinathan, G.; Tiwari, M.; Kassa, A.E. A comparative study on subtractive manufacturing and additive manufacturing. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 6892641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B.; Khorasani, M.; Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B.; Khorasani, M. Development of additive manufacturing technology. In Additive Manufacturing Technologies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 23–51. [Google Scholar]

- Savsani, S.; Singh, S.; Mali, H.S. Additive manufacturing for prostheses development: State of the art. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2023, 29, 741–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasani, M.; Ghasemi, A.; Rolfe, B.; Gibson, I. Additive manufacturing a powerful tool for the aerospace industry. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2022, 28, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasco, J.C. Additive manufacturing for the automotive industry. In Additive Manufacturing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 505–530. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Shou, W.; Makatura, L.; Matusik, W.; Fu, K.K. 3D printing of polymer composites: Materials, processes, and applications. Matter 2022, 5, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B.; Khorasani, M.; Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B.; Khorasani, M. Generalized additive manufacturing process chain. In Additive Manufacturing Technologies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.; Zou, J.; Li, S.; Jamshidi, P.; Abena, A.; Forsey, A.; Moat, R.J.; Essa, K.; Wang, M.; Zhou, K. Additive manufacturing of bio-inspired multi-scale hierarchically strengthened lattice structures. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2021, 167, 103764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, X.S. Additive manufacturing of topology-optimized graded porous structures: An experimental study. JOM 2021, 73, 2022–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, B.; Gyabaah, K.Y.; Mensah, P.; Martey, A.K.; Li, G. Challenges and opportunities of vitrimers for aerospace applications: A roadmap for industrial adoption. Clean. Mater. 2025, 18, 100353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belei, C.; Joeressen, J.; Amancio-Filho, S.T. Fused-Filament Fabrication of Short Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polyamide: Parameter Optimization for Improved Performance under Uniaxial Tensile Loading. Polymers 2022, 14, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfriha, K.; Ahmadifar, M.; Shirinbayan, M.; Tcharkhtchi, A. Effect of process parameters on thermal and mechanical properties of polymer-based composites using fused filament fabrication. Polym. Compos. 2021, 42, 6025–6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, U.; Abrar, H.; Furqan, A.; Muhammad, Z.-U.-A.; Hajrah, M.; Abdullah, D.; Qamar, H.; Hassan, I.; Muhammad, A.; Djavanroodi, F. Thermo-mechanical analysis of additive manufacturing for material properties estimation of layered polymer composite. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2024, 31, 8180–8190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Etemadi, M.; Davis, B.A.; McKnight, S.H.; Williams, C.B.; Case, S.W.; Bortner, M.J. Rheological investigation of nylon-carbon fiber composites fabricated using material extrusion-based additive manufacturing. Polym. Compos. 2021, 42, 6010–6024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoundi, B.; Hajami, F. Extruded polymer instability study of the polylactic acid in fused filament fabrication process: Printing speed effects on tensile strength. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2022, 62, 4145–4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayah, N.; Smith, D.E. Correlation of Microstructural Features within Short Carbon Fiber/ABS Manufactured via Large-Area Additive-Manufacturing Beads. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satapathy, Y.; Nikitin, V.; Hana, J.; Venkatesan, K.R.; Tran, F.; Chen, S.; Shevchenko, P.; De Carlo, F.; Kettimuthu, R.; Zekriardehani, S. Multiscale porosity characterization in additively manufactured polymer nanocomposites using micro-computed tomography. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 86, 104199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; McCarthy, E.D. Fibre flow and void formation in 3D printing of short-fibre reinforced thermoplastic composites: An experimental benchmark exercise. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 37, 101686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pibulchinda, P.; Barocio, E.; Pipes, R.B. Influence of fiber orientation on deformation of additive manufactured composites. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 49, 102483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candal, M.V.; Calafel, I.; Fernandez, M.; Aranburu, N.; Aguirresarobe, R.H.; Gerrica-Echevarria, G.; Santamaria, A.; Müller, A.J. Study of the interlayer adhesion and warping during material extrusion-based additive manufacturing of a carbon nanotube/biobased thermoplastic polyurethane nanocomposite. Polymer 2021, 224, 123734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, J.P.; Warrior, H.V. Evaluation of machine learning algorithms for predictive Reynolds stress transport modeling. Acta Mech. Sin. 2022, 38, 321544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovel, J.; Greiner, R. An Introduction to Machine Learning Approaches for Biomedical Research. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 771607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.C.; Choi, J.B.; Udaykumar, H.; Baek, S. Challenges and opportunities for machine learning in multiscale computational modeling. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2023, 23, 060808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cranenburgh, S.; Wang, S.; Vij, A.; Pereira, F.; Walker, J. Choice modelling in the age of machine learning-discussion paper. J. Choice Model. 2022, 42, 100340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Gu, M. Emulating the first principles of matter: A probabilistic roadmap. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.05942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghbalian, M.; Ansari, R.; Haghighi, S. A combined molecular dynamics-finite element multiscale modeling to analyze the mechanical properties of randomly dispersed, chemisorbed carbon nanotubes/polymer nanocomposites. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2023, 30, 5159–5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthale, S.A.; Dhamal, N.A.; Shinde, D.K.; Kelkar, A.D. Polymeric hybrid nanocomposites processing and finite element modeling: An overview. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 00368504211029471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, E.; Dahl, J.C.; Evans, K.M.; Khan, T.; Alivisatos, P.; Xu, T. Using Machine Learning to Predict and Understand Complex Self-Assembly Behaviors of a Multicomponent Nanocomposite. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2203168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, T.S.; Xiong, G.; Fang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Zhou, M.; Jiang, J. Machine-learning-based monitoring and optimization of processing parameters in 3D printing. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2023, 36, 1362–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, H.; Salimi Beni, A. Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Smart Technologies for Nondestructive Evaluation. In Handbook of Nondestructive Evaluation 4.0; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 853–881. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, W.L.; Goh, G.L.; Goh, G.D.; Ten, J.S.J.; Yeong, W.Y. Progress and opportunities for machine learning in materials and processes of additive manufacturing. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2310006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, F.E.; Aydin, R.C.; Cyron, C.J.; Huber, N.; Kalidindi, S.R.; Klusemann, B. A review of the application of machine learning and data mining approaches in continuum materials mechanics. Front. Mater. 2019, 6, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, D.; Singh, S.P.; Behera, B.K. Additive manufacturing of fiber-reinforced composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 12219–12256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahshid, R.; Isfahani, M.N.; Heidari-Rarani, M.; Mirkhalaf, M. Recent advances in development of additively manufactured thermosets and fiber reinforced thermosetting composites: Technologies, materials, and mechanical properties. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 171, 107584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Perveen, F.; Chen, S.; Akram, T.; Irfan, A. Polymer composites in 3D/4D printing: Materials, advances, and prospects. Molecules 2024, 29, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarabia-Vallejos, M.A.; Rodríguez-Umanzor, F.E.; González-Henríquez, C.M.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J. Innovation in additive manufacturing using polymers: A survey on the technological and material developments. Polymers 2022, 14, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, T.A.; Fridman, A.; McLaughlin, J.; Francis, C.; Clay, A.; Narayanan, G.; Yoon, H.; Idrees, M.; Palmese, G.R.; Scala, J.L. High-performance thermosets for additive manufacturing. Innov. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 10, 2330003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S.; Venkatesh, K.; Revathy, G.; Venkatesan, M.; Venkatraman, R. Adaptive fabrication of material extrusion-AM process using machine learning algorithms for print process optimization. J. Intell. Manuf. 2024, 36, 5087–5111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.; Wang, J.; Tu, Y.P.; Chang, G.; Ren, X.; Ding, C. Robust optimization of 3D printing process parameters considering process stability and production efficiency. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 71, 103588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, F.; Taylor, R. Additive manufacturing in the context of repeatability and reliability. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2023, 32, 6589–6609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaei, A.; Ghiaasiaan, R.; Ho, I.-T.; Strayer, S.; Chang, K.-C.; Shamsaei, N.; Shao, S.; Paul, S.; Yeh, A.-C.; Tin, S. Additive manufacturing of nickel-based superalloys: A state-of-the-art review on process-structure-defect-property relationship. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 136, 101108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, K.; Samykano, M.; Kadirgama, K.; Harun, W.S.W.; Rahman, M.M. Fused deposition modeling: Process, materials, parameters, properties, and applications. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 120, 1531–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, M.; Ma, H.; Chapa-Villarreal, F.A.; Lobo, A.O.; Zhang, Y.S. Stereolithography apparatus and digital light processing-based 3D bioprinting for tissue fabrication. Iscience 2023, 26, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maines, E.M.; Porwal, M.K.; Ellison, C.J.; Reineke, T.M. Sustainable advances in SLA/DLP 3D printing materials and processes. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 6863–6897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.B.; Sathiya, P.; Varatharajulu, M. Selective laser sintering. In Advances in Additive Manufacturing Processes; Bentham Science Publishers: Karachi, Pakistan, 2021; pp. 28–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B.; Khorasani, M.; Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B.; Khorasani, M. Material jetting. In Additive Manufacturing Technologies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 203–235. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, M.; Singh, M.; Ravi, K. Fabrication of superhydrophobic PLA surfaces by tailoring FDM 3D printing and chemical etching process. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 626, 157217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Prakash, B.P.; Dileep, K.S.; Rao, S.A.; Kumar, G.V. An experimental examination on surface finish of FDM 3D printed parts. Mater. Today Proc. 2024, 115, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thumsorn, S.; Prasong, W.; Kurose, T.; Ishigami, A.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ito, H. Rheological behavior and dynamic mechanical properties for interpretation of layer adhesion in FDM 3D printing. Polymers 2022, 14, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zou, B.; Ding, S.; Li, L.; Huang, C. Effects of FDM-3D printing parameters on mechanical properties and microstructure of CF/PEEK and GF/PEEK. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2021, 34, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, V.; Das, O.; Babu, K.; Marimuthu, U.; Veerasimman, A.; Johnson, D.J.; Neisiany, R.E.; Hedenqvist, M.S.; Ramakrishna, S.; Berto, F. Fatigue behaviour of FDM-3D printed polymers, polymeric composites and architected cellular materials. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 143, 106007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hıra, O.; Yücedağ, S.; Samankan, S.; Çiçek, Ö.Y.; Altınkaynak, A. Numerical and experimental analysis of optimal nozzle dimensions for FDM printers. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 7, 823–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkertzos, P.; Kotzakolios, A.; Mantzouranis, G.; Kostopoulos, V. Nozzle temperature calibration in 3D printing. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2024, 18, 879–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farashi, S.; Vafaee, F. Effect of printing parameters on the tensile strength of FDM 3D samples: A meta-analysis focusing on layer thickness and sample orientation. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 7, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholil, A.; Asyaefudin, E.; Pinto, N.; Syaripuddin, S. Compression strength characteristics of ABS and PLA materials affected by layer thickness on FDM. Proc. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2377, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, A.; Galațanu, S.-V.; Sedmak, A.; Marșavina, L.; Trajković, I.; Popa, C.-F.; Milošević, M. Layer thickness influence on impact properties of FDM printed PLA material. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2024, 56, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, M.; Mahale, A.; Singh, S.K.; Deshmukh, S. Printing parameters and materials affecting mechanical properties of FDM-3D printed Parts: Perspective and prospects. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 50, 2269–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eryıldız, M. Effect of build orientation on mechanical behaviour and build time of FDM 3D-printed PLA parts: An experimental investigation. Eur. Mech. Sci. 2021, 5, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Khairul Nizam, M.A.N.B.; Ismail, K.I.B.; Yap, T.C. The effect of printing orientation on the mechanical properties of FDM 3D printed parts. In Enabling Industry 4.0 Through Advances in Manufacturing and Materials: Selected Articles from iM3F 2021, Malaysia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.P.; Saravanakumar, K.; Kumar, C.A.; Saravanakumar, R.; Abimanyu, B. Experimental investigation of the process parameters and print orientation on the dimensional accuracy of fused deposition modelling (FDM) processed carbon fiber reinforced ABS polymer parts. Mater. Today Proc. 2024, 98, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Additive Manufacturing by Digital Light Processing (DLP). Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 8, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouzakis, D.E. Advanced technologies in manufacturing 3D-layered structures for defense and aerospace. In Lamination-Theory and Application; INTECH: Vienna, Austria, 2018; Volume 74331. [Google Scholar]

- Al Rashid, A.; Khan, S.A.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G.; Koç, M. Additive manufacturing of polymer nanocomposites: Needs and challenges in materials, processes, and applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 910–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unkovskiy, A.; Schmidt, F.; Beuer, F.; Li, P.; Spintzyk, S.; Kraemer Fernandez, P. Stereolithography vs. direct light processing for rapid manufacturing of complete denture bases: An In Vitro accuracy analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, Q. An approach to improve the resolution of DLP 3D printing by parallel mechanism. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat Sarmadi, B.; Schmidt, F.; Beuer, F.; Metin, D.S.; Simeon, P.; Nicic, R.; Unkovskiy, A. The effect of build angle and artificial aging on the accuracy of SLA-and DLP-printed occlusal devices. Polymers 2024, 16, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.C.; Yang, C.C.; Levon, J.A.; Chu, T.M.G.; Morton, D.; Lin, W.S. The effects of additive manufacturing technologies and finish line designs on the trueness and dimensional stability of 3D-printed dies. J. Prosthodont. 2023, 32, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vichi, A.; Balestra, D.; Louca, C. Effect of different finishing systems on surface roughness and gloss of a 3D-printed material for permanent dental use. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellakany, P.; Fouda, S.M.; AlGhamdi, M.A.; Aly, N.M. Comparison of the color stability and surface roughness of 3-unit provisional fixed partial dentures fabricated by milling, conventional and different 3D printing fabrication techniques. J. Dent. 2023, 131, 104458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, M.; Váz, P.; Silva, J.; Martins, P. Head-to-Head Evaluation of FDM and SLA in Additive Manufacturing: Performance, Cost, and Environmental Perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Luo, K.; Spintzyk, S.; Unkovskiy, A.; Li, P.; Xu, S.; Fernandez, P.K. Post-processing of DLP-printed denture base polymer: Impact of a protective coating on the surface characteristics, flexural properties, cytotoxicity, and microbial adhesion. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, 2062–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, H.N. A study on effects of curing and machining conditions in post-processing of SLA additive manufactured polymer. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 119, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abela, S. Washing and Post-Processing Procedures. In Digital Orthodontics: Providing a Contemporary Treatment Solution; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Petrov, L.; Bojović, B.; Golubović, Z.; Sedmak, A.; Mišković, Ž.; Trajković, I.; Milošević, M. Experimental Mechanical Characterization of Parts Manufactured by SLA and DLP Technologies. Struct. Integr. Life 2023, 23, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Pop, S.I.; Dudescu, M.; Mihali, S.G.; Păcurar, M.; Bratu, D.C. Effects of disinfection and steam sterilization on the mechanical properties of 3D SLA-and DLP-printed surgical guides for orthodontic implant placement. Polymers 2022, 14, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, S.; Dudescu, M.; Contac, L.R.; Pop, R. Evaluation of the tensile properties of polished and unpolished 3D SLA-and DLP-Printed specimens used for surgical guides fabrication. Acta Stomatol. Marisiensis J. 2023, 6, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B.; Khorasani, M.; Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B.; Khorasani, M. Binder jetting. In Additive Manufacturing Technologies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 237–252. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafaei, A.; Elliott, A.M.; Barnes, J.E.; Li, F.; Tan, W.; Cramer, C.L.; Nandwana, P.; Chmielus, M. Binder jet 3D printing—Process parameters, materials, properties, modeling, and challenges. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 119, 100707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Manogharan, G. Optimization of Binder Jetting Using Taguchi Method. JOM 2017, 69, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderrama-Armendariz, C.O.; Arbelaez-Rios, S.E.; Martel-Estrada, S.-A.; Maldonado-Macias, A.A.; MacDonald, E.; Aguilar-Duque, J.I. Recovery of residual polyamide (PA12) from polymer powder bed fusion additive manufacturing process through a binder jetting process. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2024, 30, 970–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xiao, F.; Gao, Y. SiC Powder Binder Jetting 3D Printing Technology: A Review of High-Performance SiC-Based Component Fabrication and Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Song, X.; Han, S.; Abbassi, F.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, B.; Wang, X.; Araby, S. Mechanical and functional properties of polyamide/graphene nanocomposite prepared by chemicals free-approach and selective laser sintering. Compos. Commun. 2022, 36, 101396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Ding, B.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cui, Z. 4D printing of polyamide 1212 based shape memory thermoplastic polyamide elastomers by selective laser sintering. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 92, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbay Kisasöz, B.; Koç, E. Thermoplastic polymers and polymer composites used in selective laser sintering (SLS) method. In Springer Handbook of Additive Manufacturing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 585–595. [Google Scholar]

- Häfele, T.; Schneberger, J.-H.; Buchholz, S.; Vielhaber, M.; Griebsch, J. The impact of geometric complexity on manufacturing process efficiency of Selective Laser Sintering. Procedia CIRP 2023, 120, 968–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrpouya, M.; Vahabi, H.; Barletta, M.; Laheurte, P.; Langlois, V. Additive manufacturing of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) biopolymers: Materials, printing techniques, and applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 127, 112216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Kim, H.C.; De Kleine, R.; Soo, V.K.; Kiziltas, A.; Compston, P.; Doolan, M. Life cycle energy and greenhouse gas emissions implications of polyamide 12 recycling from selective laser sintering for an injection-molded automotive component. J. Ind. Ecol. 2022, 26, 1378–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupone, F.; Padovano, E.; Pietroluongo, M.; Giudice, S.; Ostrovskaya, O.; Badini, C. Optimization of selective laser sintering process conditions using stable sintering region approach. Express Polym. Lett. 2021, 15, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, N.; Foerster, A.; Aboulkhair, N.T. Material Jetting. In Springer Handbook of Additive Manufacturing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 371–387. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.B.; Bezek, L.B. Material Jetting of Polymers. In Additive Manufacturing Processes; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2020; pp. 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, S.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Tang, Y. Additive manufacturing of polymeric composites from material processing to structural design. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 219, 108903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.P.; Parameswaran, C.; Idrees, M.; Rasaki, A.S.; Liu, C.; Chen, Z.; Colombo, P. Additive manufacturing of polymer-derived ceramics: Materials, technologies, properties and potential applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 128, 100969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Xie, Z.; Wu, K.; Fu, Q. Controlled vertically aligned structures in polymer composites: Natural inspiration, structural processing, and functional application. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2103495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, D.; Singh, S.P.; Behera, B.K. Mechanical, thermal, and microstructural analysis of 3D printed short carbon fiber-reinforced nylon composites across diverse infill patterns. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 1671–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samir, S.; Gewali, J.P.; Singh, T.; Debbarma, K.; Mazumdar, S.; Lone, F.; Daniella, U.E. Introduction to polymer composites in Aerospace. CNSE J. 2024, 1, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.M.; Raghav, G.R.; Jeen Robert, R.B. PEEK-based 3D printing: A paradigm shift in implant revolution for healthcare. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 2024, 63, 680–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhy, C.; Suryakumar, S.; Bhattacharjee, D. Optimizing PEEK impact strength through multi-objective FDM 3D printing. J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2023, 17, 9725–9741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, R.; Vijayakumar, P.; Rusho, M.A.; Kumar, A.; Shankar, K.V.; Thirugnanasambandam, A.K. Selection and optimization of Carbon-Reinforced Polyether Ether Ketone process parameters in 3D Printing—A rotating component application. Polymers 2024, 16, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Ding, Y.; Lei, Z.; Welch, S.; Zhang, W.; Dunn, M.; Yu, K. 3D printing of continuous fiber-reinforced thermoset composites. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 40, 101921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoni, G.; Gercci, Y.; Dodiuk, H.; Kenig, S.; Tenne, R. Radiation curing thermosets. In Handbook of Thermoset Plastics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 891–915. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Qiu, J.; Wang, S. In-situ curing of 3D printed freestanding thermosets. J. Adv. Manuf. Process. 2022, 4, e10114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.J.; Peterson, A.M.; Park, J.H. Chapter 23-3D printing. In Handbook of Thermoset Plastics, 4th ed.; Dodiuk, H., Ed.; William Andrew Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 1021–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, E.F.; Wanasinghe, S.V.; Flynn, A.E.; Dodo, O.J.; Sparks, J.L.; Baldwin, L.A.; Tabor, C.E.; Durstock, M.F.; Konkolewicz, D.; Thrasher, C.J. 3D-printed self-healing elastomers for modular soft robotics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 28870–28877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nethani, H.; Jangitwar, A.; Gupta, S.; Kandasubramanian, B. Silicone-Based Additive Manufacturing. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 2024, 64, 998–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasiri, A.; Brabazon, D. Materials used within polymer matrix composites (PMCs) and PCM production via additive manufacturing. Encycl. Mater. Compos. 2021, 2, 837–846. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, K.I.; Yap, T.C.; Ahmed, R. 3D-printed fiber-reinforced polymer composites by fused deposition modelling (FDM): Fiber length and fiber implementation techniques. Polymers 2022, 14, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.D.; Yue, L.; Kuang, X.; Roach, D.J.; Dunn, M.L.; Qi, H.J. A hybrid additive manufacturing process for production of functional fiber-reinforced polymer composite structures. J. Compos. Mater. 2023, 57, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Dutta, N.K.; Roy Choudhury, N. Work function engineering of graphene. Nanomaterials 2014, 4, 267–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanthi, P.P.; Kumar, M.N.; Chowdary, M.S.; Madhav, V.V.; Saxena, K.K.; Mohammed, K.A.; Khan, M.I.; Upadhyay, G.; Eldin, S.M. Mechanical properties of carbon fiber reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene filled epoxy composites: Experimental and numerical investigations. Mater. Res. Express 2023, 10, 025308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, C.; Ejiofor, O. Mechanics and computational homogenization of effective material properties of functionally graded (Composite) material plate FGM. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2023, 13, 128–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, S.P. Enhancing interfacial adhesion in carbon fiber-reinforced composites through polydopamine-assisted nanomaterial coatings. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 6768–6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, A.; Carreiró, F.; Oliveira, A.M.; Neves, A.; Pires, B.; Venkatesh, D.N.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Eder, P.; Silva, A.M. Polymeric nanoparticles: Production, characterization, toxicology and ecotoxicology. Molecules 2020, 25, 3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zwingmann, B.; Schlaich, M. Carbon fiber reinforced polymer for cable structures—A review. Polymers 2015, 7, 2078–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Han, M.; Jiang, Y.; Ng, E.L.L.; Zhang, Y.; Owh, C.; Song, Q.; Li, P.; Loh, X.J.; Chan, B.Q.Y. Electrically conductive polymers for additive manufacturing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 5337–5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsden, A.J.; Papageorgiou, D.; Valles, C.; Liscio, A.; Palermo, V.; Bissett, M.; Young, R.; Kinloch, I. Electrical percolation in graphene–polymer composites. 2D Mater. 2018, 5, 032003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yu, M.-Y.; Yu, Z.-Z.; Nicolosi, V. Design and advanced manufacturing of electromagnetic interference shielding materials. Mater. Today 2023, 66, 245–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retailleau, C.; Eddine, J.A.; Ndagijimana, F.; Haddad, F.; Bayard, B.; Sauviac, B.; Alcouffe, P.; Fumagalli, M.; Bounor-Legaré, V.; Serghei, A. Universal behavior for electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness of polymer based composite materials. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 221, 109351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.; Sampaio, A.; Pontes, A. Composite materials with MWCNT processed by Selective Laser Sintering for electrostatic discharge applications. Polym. Test. 2022, 114, 107711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sit, S.; Nath, K.; Das, N.C.; Chakraborty, G. Superior electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness of functionalized MWCNTs filled flexible thermoplastic polymer nanocomposites. J. Elastomers Plast. 2022, 54, 975–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhao, H.; Niu, H.; Ren, Y.; Fang, H.; Fang, X.; Lv, R.; Maqbool, M.; Bai, S. Highly thermally conductive 3D printed graphene filled polymer composites for scalable thermal management applications. Acs Nano 2021, 15, 6917–6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleifer, S.L.; Regev, O. Additive manufacturing of anisotropic graphene-based composites for thermal management applications. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 70, 103567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Niu, H.; Zhao, H.; Kang, L.; Ren, Y.; Lv, R.; Ren, L.; Maqbool, M.; Bashir, A.; Bai, S. Highly anisotropic thermal conductivity of three-dimensional printed boron nitride-filled thermoplastic polyurethane composites: Effects of size, orientation, viscosity, and voids. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 14568–14578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roudný, P.; Kašparová, J.; Gransow, P.; Drašar, Č.; Spiehl, D.; Syrový, T. Polycarbonate composites for material extrusion-based additive manufacturing of thermally conductive objects. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 79, 103901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, N.; Strasser, C.; Tanda, A.; Archodoulaki, V.M.; Burgstaller, C. Influence of printing direction and filler orientation on the thermal conductivity of 3D printed heat sinks. SPE Polym. 2024, 5, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.-B.; Kim, M.; Hyun, K.; Ahn, C.-W.; Kim, C.B. Thermally conductive 2D filler orientation control in polymer using thermophoresis. Polym. Test. 2023, 117, 107838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchert, D.S.; Tahmasebipour, A.; Liu, X.; Mancini, J.; Moran, B.; Giera, B.; Joshipura, I.D.; Shusteff, M.; Meinhart, C.D.; Cobb, C.L. Anisotropic thermally conductive composites enabled by acoustophoresis and stereolithography. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2201687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, B.; Taheri-Behrooz, F. Advanced additive manufacturing of self-healing composites: Exploiting shape memory alloys for autonomous restoration under mixed-mode loading. Mater. Des. 2023, 234, 112379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G. Self-Healing Composites: Shape Memory Polymer Based Structures; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Yu, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, P.; Chi, Y.; Jian, X.; Song, Y.; Xu, J. Dual rapid self-healing and easily recyclable carbon fiber reinforced vitrimer composites. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 480, 148147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ng, E.L.L.; Han, D.X.; Yan, Y.; Chan, S.Y.; Wang, J.; Chan, B.Q.Y. Self-healing polymeric materials and composites for additive manufacturing. Polymers 2023, 15, 4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyabaah, K.Y.; Konlan, J.; Tetteh, O.; Jahan, M.; Jackson, E.; Mensah, P.; Li, G. 3D printable regolith filled shape memory vitrimer composite for extraterrestrial application. J. Compos. Mater. 2024, 58, 2639–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado-Garcia, I.; Garcia-Gonzalez, D.; Garzon-Hernandez, S.; Rusinek, A.; Robles, G.; Martinez-Tarifa, J.M.; Arias, A. Conductive 3D printed PLA composites: On the interplay of mechanical, electrical and thermal behaviours. Compos. Struct. 2021, 265, 113744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinchi, A.; Sola, A. Embedding function within additively manufactured parts: Materials challenges and opportunities. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2023, 25, 2300395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Noman, A.; Kumar, B.K.; Dickens, T. Field assisted additive manufacturing for polymers and metals: Materials and methods. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2023, 18, e2256707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trembecka-Wójciga, K.; Ortyl, J. Enhancing 3D printed ceramic components: The function of dispersants, adhesion promoters, and surface-active agents in Photopolymerization-based additive manufacturing. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 332, 103251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zohdi, N.; Yang, R. Material anisotropy in additively manufactured polymers and polymer composites: A review. Polymers 2021, 13, 3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.N.; Ishak, M.R.; Hannah, M.Z.Z. The effect of fused deposition modeling parameters (FDM) on the mechanical properties of polylactic acid (PLA) printed parts. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Mech 2024, 123, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algarni, M.; Ghazali, S. Comparative study of the sensitivity of PLA, ABS, PEEK, and PETG’s mechanical properties to FDM printing process parameters. Crystals 2021, 11, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemipour, S.; Mammeri, A. Role of Controlling Factors in 3D Printing. In Industrial Strategies and Solutions for 3D Printing: Applications and Optimization; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cojocaru, V.; Frunzaverde, D.; Miclosina, C.-O.; Marginean, G. The influence of the process parameters on the mechanical properties of PLA specimens produced by fused filament fabrication—A review. Polymers 2022, 14, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Gilmer, E.L.; Biria, S.; Bortner, M.J. Importance of polymer rheology on material extrusion additive manufacturing: Correlating process physics to print properties. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 1218–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzos, E.; Van Hemelrijck, D.; Pyl, L. Modeling elastic properties of 3D printed composites using real fibers. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 232, 107581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimašauskas, M.; Jasiūnienė, E.; Kuncius, T.; Rimašauskienė, R.; Cicėnas, V. Investigation of influence of printing parameters on the quality of 3D printed composite structures. Compos. Struct. 2022, 281, 115061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, J.; Koirala, P.; Shen, Y.-L.; Tehrani, M. Eliminating voids and reducing mechanical anisotropy in fused filament fabrication parts by adjusting the filament extrusion rate. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 80, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetrick, D.R.; Sanei, S.H.R.; Ashour, O. Void content reduction in 3D printed glass fiber-reinforced polymer composites through temperature and pressure consolidation. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourali, M.; Peterson, A.M. The effects of toolpath and glass fiber reinforcement on bond strength and dimensional accuracy in material extrusion of a hot melt adhesive. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 58, 103056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Chen, X.; Xu, S.; Zhao, T. Evolution of Manufacturing Defects of 3D-Printed Thermoplastic Composites with Processing Parameters: A Micro-CT Analysis. Materials 2023, 16, 6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Fan, J.; Li, G. Recyclable thermoset shape memory polymers with high stress and energy output via facile UV-curing. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 11479–11487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharana, A.P.; Dixit, A.R. 2-Dimensional strain mapping and post curing effects on viscoelastic properties of glass fiber infused photocurable composites prepared using Vat-photopolymerization process. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2025, 31, 742–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttridge, C.; Shannon, A.; O’Sullivan, A.; O’Sullivan, K.J.; O’Sullivan, L.W. Effects of post-curing duration on the mechanical properties of complex 3D printed geometrical parts. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 156, 106585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štaffová, M.; Ondreáš, F.; Svatík, J.; Zbončák, M.; Jančář, J.; Lepcio, P. 3D printing and post-curing optimization of photopolymerized structures: Basic concepts and effective tools for improved thermomechanical properties. Polym. Test. 2022, 108, 107499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livolsi, F.; May, T.; Caputo, D.; Fouladi, K.; Eslami, B. Multiscale study on effect of humidity on shape memory polymers used in three-dimensional printing. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2021, 143, 091010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniran, O.; Cong, W.; Bediako, E.; Adu, S.P. Environmental affected mechanical performance of additively manufactured carbon fiber–reinforced plastic composites. J. Compos. Mater. 2022, 56, 1139–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruère, V.; Lion, A.; Holtmannspoetter, J.; Johlitz, M. Under-extrusion challenges for elastic filaments: The influence of moisture on additive manufacturing. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 7, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, G.D.; Wong, K.K.; Tan, N.; Seet, H.L.; Nai, M.L.S. Large-format additive manufacturing of polymers: A review of fabrication processes, materials, and design. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2024, 19, e2336160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrol, A.; Góralski, B.; Wichniarek, R. The influence of moisture absorption and desorption by the ABS filament on the properties of additively manufactured parts using the fused deposition modeling method. Materials 2024, 17, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramian, J.; Ramian, J.; Dziob, D. Thermal Deformations of Thermoplast during 3D Printing: Warping in the Case of ABS. Materials 2021, 14, 7070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altıparmak, S.C.; Xiao, B. A market assessment of additive manufacturing potential for the aerospace industry. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 68, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Riccio, A. A systematic review of design for additive manufacturing of aerospace lattice structures: Current trends and future directions. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2024, 149, 101021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ng, N.P.H.; Jung, J.; Moon, S.K. Additive manufacturing for automotive industry: Status, challenges and future perspectives. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Singapore, 18–21 December 2023; pp. 1431–1436. [Google Scholar]

- Tom, T.; Sreenilayam, S.P.; Brabazon, D.; Jose, J.P.; Joseph, B.; Madanan, K.; Thomas, S. Additive manufacturing in the biomedical field-recent research developments. Results Eng. 2022, 16, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M. Additive manufacturing processes in medical applications. Materials 2021, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.M.; Amudhan, K.; Ezhilmaran, V.; Jeen Robert, R.B. Transformative applications of additive manufacturing in biomedical engineering: Bioprinting to surgical innovations. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 2024, 48, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrycky, C.; Wang, Z.; Kim, K.; Kim, D.-H. 3D bioprinting for engineering complex tissues. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, E.H.Y.; Yu, F.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Z. 3D Bioprinting for Next-Generation Personalized Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaali, M.J.; Moosabeiki, V.; Rajaai, S.M.; Zhou, J.; Zadpoor, A.A. Additive manufacturing of biomaterials—Design principles and their implementation. Materials 2022, 15, 5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, A.M.; Pei, Y.; Jayawardhana, B.; Kottapalli, A.G.P. Biomimetic soft polymer microstructures and piezoresistive graphene MEMS sensors using sacrificial metal 3D printing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liman, M.L.R.; Islam, M.T.; Hossain, M.M. Mapping the progress in flexible electrodes for wearable electronic textiles: Materials, durability, and applications. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2022, 8, 2100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krifa, M. Electrically conductive textile materials—Application in flexible sensors and antennas. Textiles 2021, 1, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckdashel, R.R.; Khadse, N.; Park, J.H. Smart E-textiles: Overview of components and outlook. Sensors 2022, 22, 6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malley, S.; Reina, C.; Nacy, S.; Gilles, J.; Koohbor, B.; Youssef, G. Predictability of mechanical behavior of additively manufactured particulate composites using machine learning and data-driven approaches. Comput. Ind. 2022, 142, 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.; Keist, J.; Palmer, T. Defects in metal additive manufacturing processes. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 4808–4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anang, A.N.; Alade, B.; Olabiyi, R. Additive Manufacturing of Metal Alloys: Exploring Microstructural Evolution and Mechanical Properties. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2024, 5, 2373–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi-Hafshejani, P.; Soltani-Tehrani, A.; Shamsaei, N.; Mahjouri-Samani, M. Laser incidence angle influence on energy density variations, surface roughness, and porosity of additively manufactured parts. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 50, 102572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udu, A.G.; Osa-Uwagboe, N.; Adeniran, O.; Aremu, A.; Khaksar, M.G.; Dong, H. A machine learning approach to characterise fabrication porosity effects on the mechanical properties of additively manufactured thermoplastic composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2024, 44, 07316844241236696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yang, Y.; Moghaddam, N.S. Process modeling in laser powder bed fusion towards defect detection and quality control via machine learning: The state-of-the-art and research challenges. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 73, 961–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsazadeh, M.; Sharma, S.; Dahotre, N. Towards the next generation of machine learning models in additive manufacturing: A review of process dependent material evolution. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 135, 101102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erps, T.; Foshey, M.; Luković, M.K.; Shou, W.; Goetzke, H.H.; Dietsch, H.; Stoll, K.; von Vacano, B.; Matusik, W. Accelerated discovery of 3D printing materials using data-driven multiobjective optimization. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabf7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, A.; Duan, C.; Kulik, H.J. Audacity of huge: Overcoming challenges of data scarcity and data quality for machine learning in computational materials discovery. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2022, 36, 100778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhou, J.; Sun, Z. Materials data toward machine learning: Advances and challenges. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 3965–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loisel, J.; Cornuéjols, A.; Laguerre, O.; Tardet, M.; Cagnon, D.; de Lamotte, O.D.; Duret, S. Machine learning for temperature prediction in food pallet along a cold chain: Comparison between synthetic and experimental training dataset. J. Food Eng. 2022, 335, 111156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karande, P.; Gallagher, B.; Han, T.Y.-J. A strategic approach to machine learning for material science: How to tackle real-world challenges and avoid pitfalls. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 7650–7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, W.; Sun, L. Mechanical characterization of 3D printed continuous carbon fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 227, 109618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, M.; Colucci, G.; Diana, A.; Sin, A.; Tonani, A.; Maurino, V. Thermal properties and decomposition products of modified cotton fibers by TGA, DSC, and Py–GC/MS. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 228, 110937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, L.V.M.; de Brito, L.L.C.; Souza, D.d.H.S.; Tavares, M.I.B. Evaluation of polymeric nanocomposites. Lumen Virtus 2024, 15, 2518–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, I.; Siracusa, V. The use of thermal techniques in the characterization of bio-sourced polymers. Materials 2021, 14, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, I.; Rongpipi, S.; Govindaraju, I.; Mal, S.S.; Gomez, E.W.; Gomez, E.D.; Kalita, R.D.; Nath, Y.; Mazumder, N. An insight into microscopy and analytical techniques for morphological, structural, chemical, and thermal characterization of cellulose. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2022, 85, 1990–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhringer, P.; Sommer, D.; Haase, T.; Barteczko, M.; Sprave, J.; Stoll, M.; Karadogan, C.; Koch, D.; Middendorf, P.; Liewald, M. A strategy to train machine learning material models for finite element simulations on data acquirable from physical experiments. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2023, 406, 115894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, D.; Haufe, A.; Middendorf, P. A machine learning material model for structural adhesives in finite element analysis. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2022, 117, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, S.; Schwalbe-Koda, D.; Mohapatra, S.; Damewood, J.; Greenman, K.P.; Gómez-Bombarelli, R. Learning matter: Materials design with machine learning and atomistic simulations. Acc. Mater. Res. 2022, 3, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobeiry, N.; Poursartip, A. Theory-guided machine learning for process simulation of advanced composites. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.16010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yao, X.; Liu, K.; Tan, C.; Moon, S.K. Multisensor fusion-based digital twin in additive manufacturing for in-situ quality monitoring and defect correction. Proc. Des. Soc. 2023, 3, 2755–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbouelNour, Y.; Gupta, N. In-situ monitoring of sub-surface and internal defects in additive manufacturing: A review. Mater. Des. 2022, 222, 111063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarhalli, T.P.; Save, A.M.; Shekokar, N.M. Fundamental models in machine learning and deep learning. In Design of Intelligent Applications Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vyas, D.; Kapadia, V.V. Eagle view: An abstract evaluation of machine learning algorithms based on data properties. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Stud. 2022, 11, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.; Soleimani, S. ML-based group method of data handling: An improvement on the conventional GMDH. Complex Intell. Syst. 2021, 7, 2949–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kaur, A.; Semwal, A. Supervised and unsupervised prediction application of machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Cyber Resilience (ICCR), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 6–7 October 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ciampaglia, A.; Tridello, A.; Paolino, D.; Berto, F. Data driven method for predicting the effect of process parameters on the fatigue response of additive manufactured AlSi10Mg parts. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 170, 107500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuwono, S.; Löppenberg, M.; Arend, D.; Diprasetya, M.R.; Schwung, A. Mlpro-mpps-a versatile and configurable production systems simulator in python. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 2nd Industrial Electronics Society Annual On-Line Conference (ONCON), Virtual, 8–10 December 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehne, M.; Bartsch, K.; Bossen, B.; Emmelmann, C. Predicting melt track geometry and part density in laser powder bed fusion of metals using machine learning. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 8, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada Parra, D.; Ferreira, G.R.B.; Díaz, J.G.; Gheorghe de Castro Ribeiro, M.; Braga, A.M.B. Supervised Machine Learning Models for Mechanical Properties Prediction in Additively Manufactured Composites. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niendorf, K.; Raeymaekers, B. Using supervised machine learning methods to predict microfiber alignment and electrical conductivity of polymer matrix composite materials fabricated with ultrasound directed self-assembly and stereolithography. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2022, 206, 111233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Becerra, J.; González-Estrada, O.A.; Sánchez-Acevedo, H. Comparison of models to predict mechanical properties of FR-AM composites and a fractographical study. Polymers 2022, 14, 3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, L. A comparative study of 11 non-linear regression models highlighting autoencoder, DBN, and SVR, enhanced by SHAP importance analysis in soybean branching prediction. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challapalli, A.; Li, G. Machine learning assisted design of new lattice core for sandwich structures with superior load carrying capacity. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrin, T.; Pourali, M.; Pourkamali-Anaraki, F.; Peterson, A.M. Active learning for prediction of tensile properties for material extrusion additive manufacturing. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Hussain, A.; Amir, S.B.; Ahmed, S.H.; Aslam, S.M.H. XGBoost and random forest algorithms: An in depth analysis. Pak. J. Sci. Res. 2023, 3, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagner, A.; Ciucci, D.; Cabitza, F. Aggregation models in ensemble learning: A large-scale comparison. Inf. Fusion 2023, 90, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Teodoro, G.; Monaci, M.; Palagi, L. Unboxing tree ensembles for interpretability: A hierarchical visualization tool and a multivariate optimal re-built tree. EURO J. Comput. Optim. 2024, 12, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challapalli, A.; Li, G. 3D printable biomimetic rod with superior buckling resistance designed by machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayasudha, M.; Elangovan, M.; Mahdal, M.; Priyadarshini, J. Accurate estimation of tensile strength of 3D printed parts using machine learning algorithms. Processes 2022, 10, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaddad, W.; He, M.; Halabi, Y.; Almajhali, K.Y.M. Optimizing the material and printing parameters of the additively manufactured fiber-reinforced polymer composites using an artificial neural network model and artificial bee colony algorithm. In Structures; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 46, pp. 1781–1795. [Google Scholar]

- Nawafleh, N.; AL-Oqla, F.M. Artificial neural network for predicting the mechanical performance of additive manufacturing thermoset carbon fiber composite materials. J. Mech. Behav. Mater. 2022, 31, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, S.; Ali, A.; Anam, S.; Ahmed, M.M. An unsupervised machine learning algorithms: Comprehensive review. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 2023, 13, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rylko, N.; Stawiarz, M.; Kurtyka, P.; Mityushev, V. Study of anisotropy in polydispersed 2D micro and nano-composites by Elbow and K-Means clustering methods. Acta Mater. 2024, 276, 120116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manola, M.S.; Singh, B.; Singla, M.K.; Chohan, J.S.; Kumar, R.; Bisht, Y.S.; Alkahtani, M.Q.; Islam, S.; Ammarullah, M.I. Investigation of melt flow index and tensile properties of dual metal reinforced polymer composites for 3D printing using machine learning approach: Biomedical and engineering applications. AIP Adv. 2024, 14, 055016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Lyu, J.; Manoochehri, S. In situ process monitoring using acoustic emission and laser scanning techniques based on machine learning models. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 84, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrich, J.; Snow, Z.; Corbin, D.; Reutzel, E.W. Multi-modal sensor fusion with machine learning for data-driven process monitoring for additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 48, 102364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanpui, D.; Chandra, A.; Manna, S.; Dutta, P.S.; Chan, M.K.; Chan, H.; Sankaranarayanan, S.K. Understanding structure-processing relationships in metal additive manufacturing via featurization of microstructural images. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 231, 112566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsenan, S.A.; Al-Turaiki, I.M.; Hafez, A.M. Feature extraction methods in quantitative structure–activity relationship modeling: A comparative study. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 78737–78752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahfock, D.; McLachlan, G.J. Semi-supervised learning of classifiers from a statistical perspective: A brief review. Econom. Stat. 2023, 26, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Sanz, J.M.; Maestro-Prieto, J.-A.; Arnaiz-González, Á.; Bustillo, A. Semi-supervised learning for industrial fault detection and diagnosis: A systemic review. ISA Trans. 2023, 143, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Ni, J. A deep fuzzy semi-supervised approach to clustering and fault diagnosis of partially labeled semiconductor manufacturing data. In Proceedings of the North American Fuzzy Information Processing Society Annual Conference, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 7–9 June 2021; pp. 62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, N.V.; Hum, A.J.W.; Do, T.; Tran, T. Semi-supervised machine learning of optical in-situ monitoring data for anomaly detection in laser powder bed fusion. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2023, 18, e2129396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunselman, C.; Sheikh, S.; Mikkelsen, M.; Attari, V.; Arróyave, R. Microstructure classification in the unsupervised context. Acta Mater. 2022, 223, 117434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akers, S.; Kautz, E.; Trevino-Gavito, A.; Olszta, M.; Matthews, B.E.; Wang, L.; Du, Y.; Spurgeon, S.R. Rapid and flexible segmentation of electron microscopy data using few-shot machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 2021, 7, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, K.M.O.; Gorgônio, A.C.; Flavius Da Luz, E.G.; Canuto, A.M.D.P. An efficient approach to select instances in self-training and co-training semi-supervised methods. IEEE Access 2021, 10, 7254–7276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, D.N.C.; Van Tung, T.; Yee, E.Y.K. Quality monitoring for injection moulding process using a semi-supervised learning approach. In Proceedings of the IECON 2021–47th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Toronto, ON, Canada, 13–16 October 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Z.; Dong, Y.; Yu, Z.; Lv, H.; Lv, Z. Semi-supervised support vector machine for digital twins based brain image fusion. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 705323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W. A co-training style semi-supervised artificial neural network modeling and its application in thermal conductivity prediction of polymeric composites filled with BN sheets. Energy AI 2021, 4, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. Beyond Labels: A Comprehensive Review of Self-Supervised Learning and Intrinsic Data Properties. J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 4, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. Beyond supervised: The rise of self-supervised learning in autonomous systems. Information 2024, 15, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, S.; D’Innocente, A.; Liao, Y.; Carlucci, F.M.; Caputo, B.; Tommasi, T. Self-supervised learning across domains. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 5516–5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albelwi, S. Survey on self-supervised learning: Auxiliary pretext tasks and contrastive learning methods in imaging. Entropy 2022, 24, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S.; Shariffdeen, R.; Rasnayaka, S.; Kasthuriarachchi, N. Self-supervised vision transformers for malware detection. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 103121–103135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magar, R.; Wang, Y.; Barati Farimani, A. Crystal twins: Self-supervised learning for crystalline material property prediction. npj Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabin, M.; Kabir, A.N.B.; Kabir, M.K.; Choi, H.-J.; Uddin, J. Contrastive self-supervised representation learning framework for metal surface defect detection. J. Big Data 2023, 10, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, D.; Mateus, R.; Balestriero, R. Self-Supervised Anomaly Detection in the Wild: Favor Joint Embeddings Methods. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.04289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.-J.; Chen, C.-S. Foundation model for composite microstructures: Reconstruction, stiffness, and nonlinear behavior prediction. Mater. Des. 2025, 257, 114397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.-J. Foundation Model for Composite Materials and Microstructural Analysis. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.06565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.L.K.; Gonzales, C.; Spellings, M.; Galkin, M.; Miret, S.; Kumar, N. Towards foundation models for materials science: The open matsci ml toolkit. In Proceedings of the SC’23 Workshops of the International Conference on High Performance Computing, Network, Storage, and Analysis, Denver, CO, USA, 12–17 November 2023; pp. 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, R.d.R.; Capron, B.D.O.; Secchi, A.R.; de Souza, M.B., Jr. Where reinforcement learning meets process control: Review and guidelines. Processes 2022, 10, 2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S. Integrating Machine Learning for Optimal Path Planning. J. Comput. Technol. Appl. Math. 2025, 2, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmadhikari, S.; Menon, N.; Basak, A. A reinforcement learning approach for process parameter optimization in additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 71, 103556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Shen, B.; Law, A.C.C.; Kong, Z. Reinforcement Learning-based Defect Mitigation for Quality Assurance of Additive Manufacturing. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 65, 822–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladosz, P.; Weng, L.; Kim, M.; Oh, H. Exploration in deep reinforcement learning: A survey. Inf. Fusion 2022, 85, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Xie, L. A survey on multi-agent reinforcement learning and its application. J. Autom. Intell. 2024, 3, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasme, P.; Vagadiya, J.; Bhatia, U. Enhancing predictive skills in physically-consistent way: Physics informed machine learning for hydrological processes. J. Hydrol. 2022, 615, 128618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.; Griesemer, S.; Cao, D.; Seo, S.; Liu, Y. When physics meets machine learning: A survey of physics-informed machine learning. Mach. Learn. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2025, 1, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyyedi, A.; Bohlouli, M.; Oskoee, S.N. Machine learning and physics: A survey of integrated models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Du, Z.; Liu, C.; Zheng, Y.; Cui, T.; Mei, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Guo, X. Problem-independent machine learning (PIML)-based topology optimization—A universal approach. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 2022, 56, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, D.E.; Woodward, W.H.; Van Duin, A.C. Machine learning-assisted hybrid ReaxFF simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 6705–6712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, B.; Peters, A.; Li, G.; Hei, X. Generative Design of Thermoset Shape Memory Polymers Driven by Chemical Group: A Conditional Variational Autoencoder Approach. J. Polym. Sci. 2025, 63, 1334–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmankar, A.P.; Challa, J.S.; Singh, A.R.; Regalla, S.P. A Review of the Applications of Machine Learning for Prediction and Analysis of Mechanical Properties and Microstructures in Additive Manufacturing. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2024, 24, 120801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyeniskhan, N.; Keutayeva, A.; Kazbek, G.; Ali, M.H.; Shehab, E. Integrating machine learning model and digital twin system for additive manufacturing. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 71113–71126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horr, A.M. Real-time Modelling and ML Data Training for Digital Twinning of Additive Manufacturing Processesa? BHM Berg-Und Hüttenmännische Monatshefte 2024, 169, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challapalli, A.; Konlan, J.; Li, G. Inverse machine learning discovered metamaterials with record high recovery stress. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 244, 108029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, J.B.; Chowdhury, S.; Ali, N.M. An investigation of the ensemble machine learning techniques for predicting mechanical properties of printed parts in additive manufacturing. Decis. Anal. J. 2024, 12, 100492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.J.; Barocio, E.; Pipes, R.B. A machine learning approach to determine the elastic properties of printed fiber-reinforced polymers. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 220, 109293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, A.; Alinia, M.; Kamarian, S.; Saber-Samandari, S.; Li, G.; Song, J.-I. Design optimization of additively manufactured sandwich beams through experimentation, machine learning, and imperialist competitive algorithm. J. Eng. Des. 2024, 35, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, J.N.; Gorji, M.B.; Mohr, D. Modeling structure-property relationships with convolutional neural networks: Yield surface prediction based on microstructure images. Int. J. Plast. 2023, 163, 103506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Feng, X.; Konlan, J.; Mensah, P.; Li, G. Overcoming the barrier: Designing novel thermally robust shape memory vitrimers by establishing a new machine learning framework. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 30049–30065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, W.; Ai, H.; Zhou, H.; Feng, L.; Cheng, L.; Guo, R.; Song, X. Application of machine learning in predicting the thermal conductivity of single-filler polymer composites. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 109116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Lu, W.; Olofsson, T.; Zhuang, X.; Rabczuk, T. Stochastic interpretable machine learning based multiscale modeling in thermal conductivity of Polymeric graphene-enhanced composites. Compos. Struct. 2024, 327, 117601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Vu-Bac, N.; Zhuang, X.; Fu, X.; Rabczuk, T. Stochastic integrated machine learning based multiscale approach for the prediction of the thermal conductivity in carbon nanotube reinforced polymeric composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 224, 109425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.W.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, P.; Hippalgaonkar, K.; Senthilnath, J.; Chellappan, V. Explainable machine learning to enable high-throughput electrical conductivity optimization and discovery of doped conjugated polymers. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 295, 111812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Ng, E.L.L.; Zhang, Y.; Owh, C.; Wang, F.; Song, Q.; Feng, T.; Zhang, B.; Li, P. Progress and opportunities in additive manufacturing of electrically conductive polymer composites. Mater. Today Adv. 2023, 17, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Huang, P.; Li, Y.-Q.; Fu, S.-Y. Improved bond strength, reduced porosity and enhanced mechanical properties of 3D-printed polyetherimide composites by carbon nanotubes. Compos. Commun. 2022, 30, 101083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, S.; Kandasamy, R.; Venkatachalam, R.; Gunalan, M.; Dhairiyasamy, R. Advances in Optimizing Mechanical Performance of 3D-Printed Polymer Composites: A Microstructural and Processing Enhancements Review. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2024, 2024, 3168252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.S.; Almutahhar, M.; Sattar, K.; Alhajeri, A.; Nazir, A.; Ali, U. Deep learning based porosity prediction for additively manufactured laser powder-bed fusion parts. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 7330–7335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Cervera, M.; Chiumenti, M.; Lin, X. Residual stresses control in additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2021, 5, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.S.; Mourad, A.-H.I.; Harib, K.H.; Vijayavenkataraman, S. Recent developments in the application of machine-learning towards accelerated predictive multiscale design and additive manufacturing. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2023, 18, e2141653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.F.; Alam, A.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Alam, M.S.; Rafat, Y.; Salik, N.; Al-Saidan, I. Real-time defect detection in 3D printing using machine learning. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 42, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaf, A.I.; Ahmed, H.; Khan, M.A.I.; Sezer, H. Development of Real-Time Defect Detection Techniques Using Infrared Thermography in the Fused Filament Fabrication Process. In Proceedings of the ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 29 October–2 November 2023; p. V003T003A017. [Google Scholar]

- Sicard, B.; Wu, Y.; Gadsden, S.A. Digital twin enabled asset management of machine tools. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Prognostics and Health Management (ICPHM), Spokane, WA, USA, 17–19 June 2024; pp. 285–292. [Google Scholar]

- Moller, J.; Hagerty, N.M.; Nguyen-Beck, T.S.; Hawkins, S.S.; Maffe, A.P.; Berry, R.J.; Nepal, D. Virtual Dynamic Mechanical Analysis. In Challenges in Mechanics of Time Dependent Materials Volume 2; River Publishers: Roma, Italy, 2021; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, C.; Cui, J.; Ning, N.; Zhang, L.; Tian, M. Quantitative characterization of interfacial properties of carbon black/elastomer nanocomposites and mechanism exploration on their interfacial interaction. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 222, 109367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, S.; Blanco, I. Investigation of dispersion, interfacial adhesion of isotropic and anisotropic filler in polymer composite. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qu, H.; Yu, S.; Zhang, S.X. Nondestructive investigation on close and open porosity of additively manufactured parts using an X-ray computed tomography. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 70, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, D.; Díaz, L.-C.; Jiménez, R.; Torralba, M.; Albajez, J.A.; Fabra, J.A.Y. X-Ray Computed Tomography performance in metrological evaluation and characterisation of polymeric additive manufactured surfaces. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 75, 103754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.; Seetoh, I.P.; Lai, C.Q. Machine learning assisted investigation of defect influence on the mechanical properties of additively manufactured architected materials. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 221, 107190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grierson, D.; Rennie, A.E.; Quayle, S.D. Machine learning for additive manufacturing. Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Chen, Y. Generative ai for synthetic data generation: Methods, challenges and the future. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.04190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W. Image data augmentation techniques based on deep learning: A survey. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2024, 21, 6190–6224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narikawa, R.; Fukatsu, Y.; Wang, Z.L.; Ogawa, T.; Adachi, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Ishikawa, S. Generative Adversarial Networks-Based Synthetic Microstructures for Data-Driven Materials Design. Adv. Theory Simul. 2022, 5, 2100470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kench, S.; Cooper, S.J. Generating three-dimensional structures from a two-dimensional slice with generative adversarial network-based dimensionality expansion. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2021, 3, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Feng, X.; Wick, C.; Peters, A.; Li, G. Machine learning assisted discovery of new thermoset shape memory polymers based on a small training dataset. Polymer 2021, 214, 123351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Hu, F.; Liu, Y.; Witherell, P.; Wang, C.C.; Rosen, D.W.; Simpson, T.W.; Lu, Y.; Tang, Q. Research and application of machine learning for additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 52, 102691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Xue, M.; Cong, P.; Song, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Guo, W. Machine learning for predicting fatigue properties of additively manufactured materials. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2024, 37, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wu, D. Predicting stress–strain curves using transfer learning: Knowledge transfer across polymer composites. Mater. Des. 2022, 218, 110700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.; Surananai, S.; Sainath, K.; Khan, M.Z.; Kuppusamy, R.R.P.; Suneetha, Y.K. Emerging trends in development and application of 3D printed nanocomposite polymers for sustainable environmental solutions. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 196, 112298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, D.J.; Bimrose, M.V.; Shao, C.; Tawfick, S.; King, W.P. Using machine learning to predict dimensions and qualify diverse part designs across multiple additive machines and materials. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 55, 102848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Rahmani Dehaghani, M.; Sajadi, P.; Wang, G.G. Selecting subsets of source data for transfer learning with applications in metal additive manufacturing. J. Intell. Manuf. 2024, 36, 3185–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezankhani, M.; Narayan, A.; Seethaler, R.; Milani, A.S. An active transfer learning (ATL) framework for smart manufacturing with limited data: Case study on material transfer in composites processing. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th IEEE International Conference on Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems (ICPS), Victoria, BC, Canada, 10–12 May 2021; pp. 277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, C.; Li, G. The rise of machine learning in polymer discovery. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2023, 5, 2200243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, A.; Li, G. Machine Learning-Driven Discovery of Thermoset Shape Memory Polymers With High Glass Transition Temperature Using Variational Autoencoders. J. Polym. Sci. 2025, 63, 1095–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orouji, S.; Liu, M.C.; Korem, T.; Peters, M.A. Domain adaptation in small-scale and heterogeneous biological datasets. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadp6040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, P.; Walambe, R.; Ramanna, S.; Kotecha, K. Domain adaptation: Challenges, methods, datasets, and applications. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 6973–7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]