Leveraging Publicly Accessible Sustainability Tools to Quantify Health and Climate Benefits of Hospital Climate Change Mitigation Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

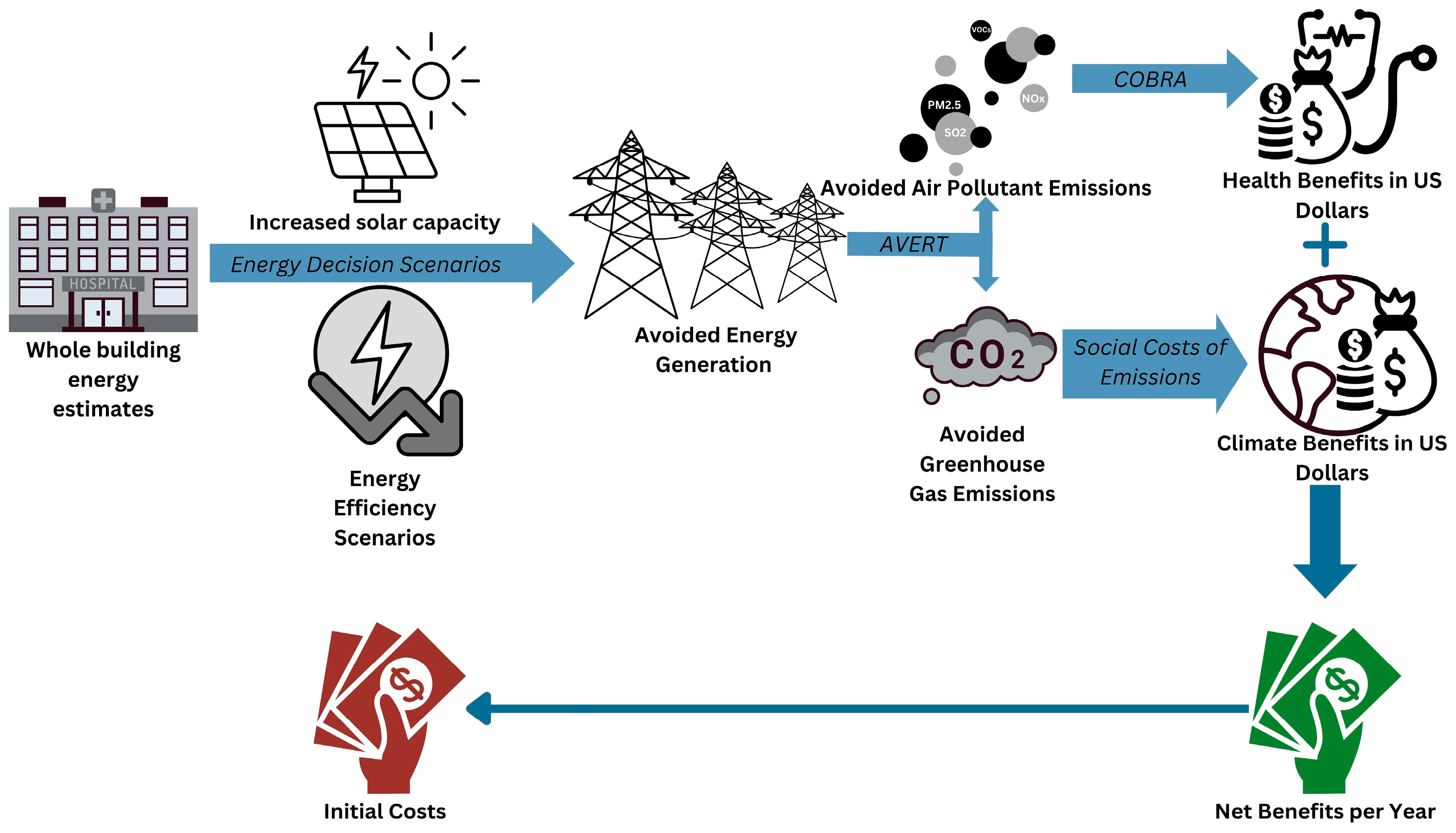

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Energy Decision Scenarios

2.2. Quantifying Benefits of Energy Decision Scenarios

2.2.1. Health Benefits

2.2.2. Climate Benefits

2.3. Scaling Energy Decision Scenarios

3. Results

3.1. Climate and Health Benefits of Chosen Energy Scenarios

3.2. Scaling Energy Decision Scenarios

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| US | United States |

| ESG | Environmental, social, and governance |

| ERE | Expanding renewable energy |

| IEE | Increasing energy efficiency |

| SO2 | Sulfur dioxide |

| NOx | Nitrogen oxides |

| NYS | New York State |

| EO | Executive Order |

| AVERT | AVoided Emissions and geneRation Tool |

| COBRA | CO-Benefits Risk Assessment |

| PM2.5 | Particulate Matter < 2.5 microns |

| VOC | Volatile organic compounds |

| NH3 | Ammonia |

| USD | United States Dollar |

| SCC | Social Cost of Carbon |

| MW | Megawatt |

References

- Hardy, J. Climate Change: Causes, Effects, and Solutions | Wiley. Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Climate+Change%3A+Causes%2C+Effects%2C+and+Solutions+-p-9780470850190 (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Romanello, M.; di Napoli, C.; Green, C.; Kennard, H.; Lampard, P.; Scamman, D.; Walawender, M.; Ali, Z.; Ameli, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; et al. The 2023 Report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: The Imperative for a Health-Centred Response in a World Facing Irreversible Harms. Lancet 2023, 402, 2346–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. The Health Impacts of Climate Change: Why Climate Action Is Essential to Protect Health. Orthop. Trauma 2022, 36, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, M.; Malik, A.; Li, M.; Fry, J.; Weisz, H.; Pichler, P.-P.; Chaves, L.S.M.; Capon, A.; Pencheon, D. The Environmental Footprint of Health Care: A Global Assessment. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e271–e279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckelman, M.J.; Sherman, J. Environmental Impacts of the U.S. Health Care System and Effects on Public Health. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Friedrich, J.; Vigna, L. Where Do Emissions Come From? 4 Charts Explain Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector. Available online: https://www.wri.org/insights/4-charts-explain-greenhouse-gas-emissions-countries-and-sectors (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- US Environmental Protection Agency. The Office of Air and Radiation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Wade, R. Climate Change and Healthcare: Creating a Sustainable and Climate-Resilient Health Delivery System. J. Healthc. Manag. 2023, 68, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Health Sector Commitments to Emissions Reduction and Resilience. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20241101222525/https://www.hhs.gov/climate-change-health-equity-environmental-justice/climate-change-health-equity/actions/health-sector-pledge/index.html (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Health Sector Commitments to Emissions Reduction and Resilience, November 2024 Update. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20241211015959/https://www.hhs.gov/climate-change-health-equity-environmental-justice/climate-change-health-equity/actions/health-sector-pledge/index.html (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Weimann, L.; Weimann, E. On the Road to Net Zero Health Care Systems: Governance for Sustainable Health Care in the United Kingdom and Germany. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Practice Greenhealth Practice Greenhealth: Sustainability Solutions for Health Care. Available online: https://practicegreenhealth.org/ (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- SION60. Massachusetts Requires Hospitals to Report Green House Gas Emissions. 2024. Available online: https://sion60.com/massachusetts-requires-hospitals-to-report-green-house-gas-emissions/ (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- The Joint Commission Sustainable Healthcare Certification. Available online: https://www.jointcommission.org/what-we-offer/certification/certifications-by-setting/hospital-certifications/sustainable-healthcare-certification/ (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Nakielski, M.L. Moving Forward with ESG, Sustainability, and Corporate Responsibility. Front. Health Serv. Manag. 2023, 40, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.R.; Haigler, E. Co-Benefits of Climate Mitigation and Health Protection in Energy Systems: Scoping Methods. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonocore, J.J.; Luckow, P.; Fisher, J.; Kempton, W.; Levy, J.I. Health and Climate Benefits of Offshore Wind Facilities in the Mid-Atlantic United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 074019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Carbon Neutrality in the UNECE Region: Integrated Life-Cycle Assessment of Electricity Sources; ECE Energy Series; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-92-1-001485-4.

- Buonocore, J.J.; Hughes, E.J.; Michanowicz, D.R.; Heo, J.; Allen, J.G.; Williams, A. Climate and Health Benefits of Increasing Renewable Energy Deployment in the United States*. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 114010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonocore, J.J.; Luckow, P.; Norris, G.; Spengler, J.D.; Biewald, B.; Fisher, J.; Levy, J.I. Health and Climate Benefits of Different Energy-Efficiency and Renewable Energy Choices. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Kovats, S.; Vardoulakis, S.; Wilkinson, P.; Woodward, A.; Li, J.; Gu, S.; Liu, X.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.; et al. Public Health Co-Benefits of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction: A Systematic Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Butkus, M. Determinants of Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A New Multiplicative Approach Analysing the Impact of Energy Efficiency, Renewable Energy, and Sector Mix. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 309, 127233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Shafiullah, M.; Papavassiliou, V.G.; Hammoudeh, S. The CO2–Growth Nexus Revisited: A Nonparametric Analysis for the G7 Economies over Nearly Two Centuries. Energy Econ. 2017, 65, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Muttarak, R.; Feng, Y. What Is the Global Causality among Renewable Energy Consumption, Financial Development, and Public Health? New Perspective of Mineral Energy Substitution. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 104036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, S.; Duan, J. California’s Economy. Available online: https://www.ppic.org/publication/californias-economy/ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Williams, A.A.; Baniassadi, A.; Izaga Gonzalez, P.; Buonocore, J.J.; Cedeno-Laurent, J.G.; Samuelson, H.W. Health and Climate Benefits of Heat Adaptation Strategies in Single-Family Residential Buildings. Front. Sustain. Cities 2020, 2, 561828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macro Poverty Outlook: Grenada 2025. Available online: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/e408a7e21ba62d843bdd90dc37e61b57-0500032021/related/mpo-grd.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- World Bank Open Data GDP (Current US$)—United States. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- World Bank Open Data GDP per Capita (Current US$)—Germany. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- van Ouwerkerk, J.; Celi Cortés, M.; Nsir, N.; Gong, J.; Figgener, J.; Zurmühlen, S.; Bußar, C.; Sauer, D.U. Quantifying Benefits of Renewable Investments for German Residential Prosumers in Times of Volatile Energy Markets. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Symonds, P.; Verschoor, N.; Chalabi, Z.; Taylor, J.; Davies, M. Home Energy Efficiency and Subjective Health in Greater London. J. Urban Health 2021, 98, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGain, F.; Naylor, C. Environmental Sustainability in Hospitals—A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2014, 19, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New York State Executive Order No. 22: Leading by Example: Directing State Agencies to Adopt a Sustainability and Decarbonization Program. Available online: https://www.governor.ny.gov/executive-order/no-22-leading-example-directing-state-agencies-adopt-sustainability-and (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Rochester Regional Health Solar Energy Powers Rochester Regional Facilities. Available online: https://www.rochesterregional.org/hub/solar-energy (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Medline Governor Hochul Announces Completion of Largest Rooftop Solar Project in New York State. Available online: https://newsroom.medline.com/releases/governor-hochul-announces-completion-of-largest-rooftop-solar-project-in-new-york-state/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- New York City Department of Citywide Administrative Services NYC DCAS & NYC Health + Hospitals Celebrate the Completion of First Ever Solar Power Installation. Available online: http://www.nyc.gov/site/dcas/news/001-24/nyc-dcas-nyc-health-hospitals-celebrate-completion-first-ever-solar-power-installation (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Albanese, J. Push to Make Upstate More Energy Efficient, Leads to Big Drop in Natural Gas, Electricity Usage; Upstate News; SUNY Upstate Medical University: Syracuse, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- US Environmental Protection Agency; The Office of Air and Radiation. Avoided Emission Rates Generated from AVERT. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/avert/avoided-emission-rates-generated-avert (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Levy, J.I.; Woo, M.K.; Penn, S.L.; Omary, M.; Tambouret, Y.; Kim, C.S.; Arunachalam, S. Carbon Reductions and Health Co-Benefits from US Residential Energy Efficiency Measures. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 034017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, D.; Holloway, T.; Harkey, M.; Rrushaj, A.; Brinkman, G.; Duran, P.; Janssen, M.; Denholm, P. Potential Air Quality Benefits from Increased Solar Photovoltaic Electricity Generation in the Eastern United States. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 175, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, A.; Chen, L.-W.A.; Lin, G.; Buttner, M.P.; Gakh, M.; Bloomfield, E.F. Air Quality Health Benefits of the Nevada Renewable Portfolio Standard. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, S.; Woody, M.; Omary, M.; Penn, S.; Chung, S.; Woo, M.; Tambouret, Y.; Levy, J. Modeling the Air Quality and Public Health Benefits of Increased Residential Insulation in the United States. In Proceedings of the Air Pollution Modeling and Its Application XXIV, Montpellier, France, 4–8 May 2015; Steyn, D.G., Chaumerliac, N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- US Environmental Protection Agency. AVERT User Manual; US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. State Energy and Environment Program AVERT Overview and Step-by-Step Instructions; US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- US Environmental Protection Agency Publications That Cite AVERT. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-04/avert_publications_04-11-24.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- US Environmental Protection Agency. COBRA User Manual, v5.2; US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2025.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Publications That Cite EPA’s CO-Benefits Risk Assessment (COBRA). Health Impacts Screening and Mapping Tool. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-04/publications-that-cite-cobra_0.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- US Environmental Protection Agency. User’s Manual for the Co-Benefits Risk Assessment Health Impacts Screening and Mapping Tool (COBRA); US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. EPA Report on the Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases: Estimates Incorporating Recent Scientific Advances; US Environmental Protection Agency, National Center for Environmental Economics Office of Policy, Climate Change Division, Office of Air and Radiation: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI Inflation Calculator. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- NYS Department of Health Hospital Bed Capacity. Available online: https://coronavirus.health.ny.gov/hospital-bed-capacity (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Bawaneh, K.; Nezami, F.G.; Rasheduzzaman, M.; Deken, B. Energy Consumption Analysis and Characterization of Healthcare Facilities in the United States. Energies 2019, 12, 3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gas-equivalencies-calculator (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Buonocore, J.J.; Lambert, K.F.; Burtraw, D.; Sekar, S.; Driscoll, C.T. An Analysis of Costs and Health Co-Benefits for a U.S. Power Plant Carbon Standard. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safaei Kouchaksaraei, E.; Kelly, K.E. Air Emission and Health Impacts of a US Industrial Energy Efficiency Program. Energy Effic. 2024, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markandya, A.; Armstrong, B.G.; Hales, S.; Chiabai, A.; Criqui, P.; Mima, S.; Tonne, C.; Wilkinson, P. Public Health Benefits of Strategies to Reduce Greenhouse-Gas Emissions: Low-Carbon Electricity Generation. Lancet 2009, 374, 2006–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amelung, D.; Fischer, H.; Herrmann, A.; Aall, C.; Louis, V.R.; Becher, H.; Wilkinson, P.; Sauerborn, R. Human Health as a Motivator for Climate Change Mitigation: Results from Four European High-Income Countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 57, 101918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.E.; Henze, D.K.; Milford, J.B. How Accounting for Climate and Health Impacts of Emissions Could Change the US Energy System. Energy Policy 2017, 102, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanello, M.; Walawender, M.; Hsu, S.-C.; Moskeland, A.; Palmeiro-Silva, Y.; Scamman, D.; Ali, Z.; Ameli, N.; Angelova, D.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; et al. The 2024 Report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: Facing Record-Breaking Threats from Delayed Action. Lancet 2024, 404, 1847–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden-Chapman, P.; Crane, J.; Matheson, A.; Viggers, H.; Cunningham, M.; Blakely, T.; O’Dea, D.; Cunningham, C.; Woodward, A.; Saville-Smith, K.; et al. Retrofitting Houses with Insulation to Reduce Health Inequalities: Aims and Methods of a Clustered, Randomised Community-Based Trial. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 2600–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulzakimin, M.; Masrom, M.A.N.; Hazli, R.; Adaji, A.A.; Seow, T.W.; Izwan, A.R.M.H. Benefits For Public Healthcare Buildings towards Net Zero Energy Buildings (NZEBs): Initial Reviews. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 713, 012042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimifard, P.; Rainbolt, M.V.; Buonocore, J.J.; Lahvis, M.; Sousa, B.; Allen, J.G. A Novel Method for Calculating the Projected Health and Climate Co-Benefits of Energy Savings through 2050. Build. Environ. 2023, 244, 110618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, R.N.; Maibach, E.; Pencheon, D.; Watts, N.; Frumkin, H. A Pathway to Net Zero Emissions for Healthcare. BMJ 2020, 371, m3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Hultman, N.; Patwardhan, A.; Qiu, Y.L. Integrating Sustainability into Climate Finance by Quantifying the Co-Benefits and Market Impact of Carbon Projects. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; Hornsey, M.J. A Social Identity Analysis of Climate Change and Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors: Insights and Opportunities. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Energy Information Administration. New York State Profile and Energy Estimates. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/state/?sid=NY (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Liu, J.; Jian, L.; Wang, W.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Dastbaz, P. The Role of Energy Storage Systems in Resilience Enhancement of Health Care Centers with Critical Loads. J. Energy Storage 2021, 33, 102086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, D.; Holloway, T.; Kladar, R.M.; Meier, P.; Ahl, D.; Harkey, M.; Patz, J. Response of Power Plant Emissions to Ambient Temperature in the Eastern United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 5838–5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, C.M.; Moeller, M.D.; Felder, F.A.; Henderson, B.H.; Carlton, A.G. High Electricity Demand in the Northeast U.S.: PJM Reliability Network and Peaking Unit Impacts on Air Quality. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 8375–8384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Institution(s) | Number of Beds | Energy Use Estimates (MW/Year) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Method 1 | Method 2 | ||

| Focus Institution | 734 | 5.23 | 3.50 |

| All Hospitals in Onondaga County, New York | 1175 | 8.37 | 5.61 |

| All Hospitals in New York State | 38,514 | 274.40 | 183.77 |

| Energy Decision | Scenario | Health Benefits ($/Year) | CO2 Avoided (Tons/Year) | Climate Benefits ($/Year) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Estimate | High Estimate | ||||

| ERE | 5% | $15,620 | $29,099 | 210 | $47,223 |

| 25% | $80,145 | $149,106 | 1060 | $238,362 | |

| 50% | $159,487 | $296,640 | 2130 | $478,973 | |

| 75% | $240,272 | $446,787 | 3190 | $717,335 | |

| 100% | $318,251 | $591,575 | 4260 | $957,946 | |

| IEE | 5% | $98,311 | $183,167 | 1210 | $272,093 |

| 10% | $192,814 | $358,219 | 2410 | $541,937 | |

| 15% | $291,405 | $541,883 | 3620 | $814,029 | |

| 20% | $391,357 | $728,171 | 4830 | $1,086,122 | |

| 25% | $485,636 | $903,045 | 6040 | $1,358,215 | |

| ERE + IEE | 5% ERE + 5% IEE | $112,869 | $210,032 | 1420 | $319,315 |

| 50% ERE + 15% IEE | $450,146 | $836,968 | 5750 | $1,293,003 | |

| 100% ERE + 25% IEE | $806,709 | $1,500,549 | 10,290 | $2,313,912 | |

| Facilities | Method | Health Benefits ($/Year) | CO2 Avoided (Tons/Year) | Climate Benefits ($/Year) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Estimate | High Estimate | ||||

| All Hospitals in Onondaga County, New York | Method 1 | $1,855,486 | $3,450,313 | 16,470 | $3,703,609 |

| Method 2 | $1,241,058 | $2,307,490 | 11,030 | $2,480,316 | |

| All Hospitals in New York State | Method 1 | $40,610,803 | $75,595,168 | 538,330 | $121,054,267 |

| Method 2 | $27,324,677 | $50,828,855 | 361,120 | $81,205,054 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Scott, T.; Corsi, P.; Williams, A.A. Leveraging Publicly Accessible Sustainability Tools to Quantify Health and Climate Benefits of Hospital Climate Change Mitigation Strategies. Green Health 2026, 2, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/greenhealth2010002

Scott T, Corsi P, Williams AA. Leveraging Publicly Accessible Sustainability Tools to Quantify Health and Climate Benefits of Hospital Climate Change Mitigation Strategies. Green Health. 2026; 2(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/greenhealth2010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleScott, Talya, Paul Corsi, and Augusta A. Williams. 2026. "Leveraging Publicly Accessible Sustainability Tools to Quantify Health and Climate Benefits of Hospital Climate Change Mitigation Strategies" Green Health 2, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/greenhealth2010002

APA StyleScott, T., Corsi, P., & Williams, A. A. (2026). Leveraging Publicly Accessible Sustainability Tools to Quantify Health and Climate Benefits of Hospital Climate Change Mitigation Strategies. Green Health, 2(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/greenhealth2010002