Sociocultural Factors Impacting Substance Misuse and Treatment: A Latent Class Analysis of Youths Undergoing Combined Treatment

Highlights

- Adolescents with high access and sociocultural privilege had more negative urine drug screens during treatment but were more likely to have an alcohol use disorder (AUD) diagnosis and to use multiple substances.

- Socioculturally disadvantaged adolescents had more emergency department visits

- During adolescent substance treatment.

- These findings suggest the importance of assessing sociocultural factors at the outset of adolescent substance treatment.

- Future research should evaluate interventions to address sociocultural factors as a way to improve outcomes and promote health equity.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

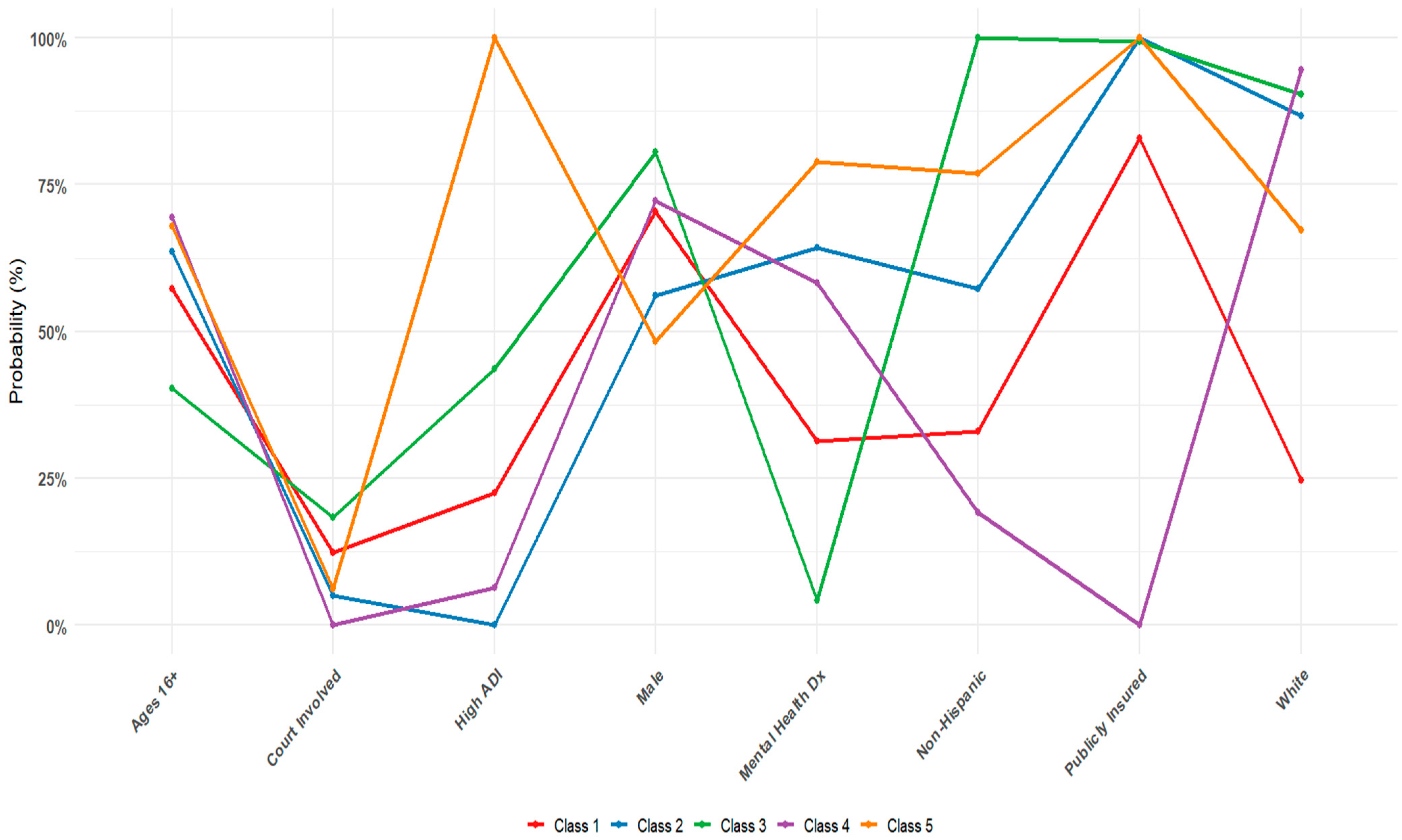

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Health. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1\ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Layman, H.M.; Thorisdottir, I.E.; Halldorsdottir, T.; Sigfusdottir, I.D.; Allegrante, J.P.; Kristjansson, A.L. Substance Use Among Youth During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2022, 24, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2024 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP25-07-007, NSDUH Series H-60). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2025. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt56287/2024-nsduh-annual-national-report.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2013–2023; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yonek, J.C.; Dauria, E.F.; Kemp, K.; Koinis-Mitchell, D.; Marshall, B.D.L.; Tolou-Shams, M. Factors Associated With Use of Mental Health and Substance Use Treatment Services by Justice-Involved Youths. Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, K.M.; Levy, S.J.; Bukstein, O.G. Adolescent Substance Use Disorders. NEJM Evid. 2022, 1, EVIDra2200051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tervo-Clemmens, B.; Gilman, J.M.; Evins, A.E.; Bentley, K.H.; Nock, M.K.; Smoller, J.W.; Schuster, R.M. Substance Use, Suicidal Thoughts, and Psychiatric Comorbidities Among High School Students. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 310–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, S.E.; Schulenberg, J.E.; Schepis, T.S.; McCabe, V.V.; Veliz, P.T. Longitudinal Analysis of Substance Use Disorder Symptom Severity at Age 18 Years and Substance Use Disorder in Adulthood. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e225324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurstone, C.; Etzig, C.; Chen, E.; Seely, H.D.; Loh, R. Mortality following adolescent substance treatment: 21-year follow-up from a single clinical site. Front. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2025, 4, 1600101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosty, E.; Ertl, A.; Sheats, K.J.; Wilson, R.; Betz, C.J.; Blair, J.M. Surveillance for violent deaths—National Violent Death Reporting System, 34 states, four California counties, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, 2017. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2020, 69, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstick, J.E.; Cunningham, R.M.; Carter, P.M. Current Causes of Death in Children and Adolescents in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1955–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, J.; Hadland, S.E. The Overdose Crisis among U.S. Adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deas, D.; Brown, E.S. Adolescent substance abuse and psychiatric comorbidities. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2006, 67, e02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, R.P.; Tsai, B.; Abela, J.R.Z. Temporal relationships among depressive symptoms, risky behavior engagement, perceived control, and gender in a sample of adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 2010, 20, 726–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundele, M.O. Behavioural and emotional disorders in childhood: A brief overview for paediatricians. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2018, 7, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verboom, C.E.; Sijtsema, J.J.; Verhulst, F.C.; Penninx, B.W.; Ormel, J. Longitudinal associations between depressive problems, academic performance, and social functioning in adolescent boys and girls. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, C.L.; Liddle, H.A.; Greenbaum, P.E.; Henderson, C.E. Impact of psychiatric comorbidity on treatment of adolescent drug abusers. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2004, 26, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trautmann, S.; Rehm, J.; Wittchen, H. The economic costs of mental disorders. EMBO Rep. 2016, 17, 1245–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, N.R. School-based harm reduction with adolescents: A pilot study. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2022, 17, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, L.R.; Maralit, A.M.; Thomas, S.E.; Rivers, S.L.; Salazar, C.A.; Anton, R.F.; Tomko, R.L.; Squeglia, L.M. Piloting of the Just Say Know prevention program: A psychoeducational approach to translating the neuroscience of addiction to youth. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2020, 47, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Seely, H.D.; Thurstone, C. Reducing barriers to promote engagement and retention in adolescent substance use treatment: Results from a quality improvement evaluation. Front. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 3, 1393401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pössel, P.; Seely, H.D.; Marchetti, I. Similarities and Differences in the Architecture of Cognitive Vulnerability to Depressive Symptoms in Black and White American Adolescents: A Network Analysis Study. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2024, 52, 1591–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seely, H.D.; Pössel, P. Equity and inclusion in prevention: Is prevention efficacious in diverse groups? J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2024, 93, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, A.; Harvey, N.; Kamanu, M.; Tendulkar, S.; Fleary, S. Barriers, facilitators, and disparities in retention for adolescents in treatment for substance use disorders: A qualitative study with treatment providers. Subst. Abus. Treat Prev. Policy 2020, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huey, S.J., Jr.; Park, A.L.; Galán, C.A.; Wang, C.X. Culturally Responsive Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Ethnically Diverse Populations. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 19, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttazzoni, A.; Doherty, S.; Minaker, L. How Do Urban Environments Affect Young People’s Mental Health? A Novel Conceptual Framework to Bridge Public Health, Planning, and Neurourbanism. Public Health Rep. 2022, 137, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinn, T.M.; Schinke, S.P.; Trent, D.N. Substance use among late adolescent urban youths: Mental health and gender influences. Addict. Behav. 2010, 35, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, P.; Calfee, C.S.; Delucchi, K.L. Practitioner’s Guide to Latent Class Analysis: Methodological Considerations and Common Pitfalls. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 49, e63–e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachid, T.; Abarda, A.; Hasbaoui, A. Latent class analysis: A review and recommendations for future applications in health sciences. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 238, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnert, K.M.; Walton, M.A.; Resko, S.; Barry, K.T.; Chermack, S.T.; Zucker, R.A.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Booth, B.M.; Blow, F.C. Latent class analysis of substance use among adolescents presenting to urban primary care clinics. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2014, 40, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karanges, E.A.; Guerin, A.A.; Malignaggi, S.; Purcell, R.; McGorry, P.; Hickie, I.; Yung, A.R.; Pantelis, C.; Amminger, G.P.; Van Dam, N.T.; et al. Substance use patterns among youth seeking help for mental illness: A latent class analysis. Addict. Behav. 2025, 167, 108355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mee-Lee, D. The Criteria: Treatment Criteria for Addictive, Substance-Related, and Co-Occurring ASAM Conditions, 3rd ed.; Change Companies: Carson City, NV, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maroko, A.R.; Doan, T.M.; Arno, P.S.; Hubel, M.; Yi, S.; Viola, D. Integrating Social Determinants of Health With Treatment and Prevention: A New Tool to Assess Local Area Deprivation. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2016, 13, 160221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denver Health. Report to the City; Denver Health: Denver, CO, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Adolescent Substance Abuse Treatment. Available online: https://www.denverhealth.org/services/behavioral-health/addiction-services/adolescent-substance-abuse-treatment (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Center for Addiction Medicine. Annual Report; Center for Addiction Medicine: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bolck, A.; Croon, M.A.; Hagenaars, J.A. Estimating latent structure models with categorical variables: One-step versus three-step estimators. Political Anal. 2004, 12, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardslee, J.; Miltimore, S.; Fine, A.; Frick, P.J.; Steinberg, L.; Cauffman, E. Under the radar or under arrest: How is adolescent boys’ first contact with the juvenile justice system related to future offending and arrests? Law Hum. Behav. 2019, 43, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgaonkar, N.T.; Baker, A.E.; Dapretto, M.; Galván, A.; Frick, P.J.; Steinberg, L.; Cauffman, E. Exploring Disproportionate Minority Contact in the Juvenile Justice System Over the Year Following First Arrest. J. Res. Adolesc. Off. J. Soc. Res. Adolesc. 2021, 31, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronson, J.; Berzofsky, M. Indicators of Mental Health Problems Reported by Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2011–2012; Bureau of Justice Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/imhprpji1112.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Hoge, M.A.; Vanderploeg, J.; Paris, M., Jr.; Lang, J.M.; Olezeski, C. Emergency Department Use by Children and Youth with Mental Health Conditions: A Health Equity Agenda. Community Ment. Health J. 2022, 58, 1225–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santo, L.; Peters, Z.J.; Davis, D.; DeFrances, C.J. Emergency department visits related to mental health disorders among children and adolescents: United States, 2018–2021. In National Health Statistics Reports; No 191; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C.J.; Andersen, S.L. Sensitive periods of substance abuse: Early risk for the transition to dependence. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2017, 25, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.M.; Calhoun, B.H.; Abdallah, D.A.; Blayney, J.A.; Schultz, N.R.; Brunner, M.; Patrick, M.E. Simultaneous Alcohol and Marijuana Use Among Young Adults: A Scoping Review of Prevalence, Patterns, Psychosocial Correlates, and Consequences. Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev. 2022, 42, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, B.; Debenham, J.; Squeglia, L.M. Alcohol and Cannabis Use and the Developing Brain. Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev. 2021, 41, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, L.; Raninen, J.; Larm, P. Early Drinking Onset and Subsequent Alcohol Use in Late Adolescence: A Longitudinal Study of Drinking Patterns. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2024, 74, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danpanichkul, P.; Duangsonk, K.; Díaz, L.A.; Chen, V.L.; Rangan, P.; Sukphutanan, B.; Dutta, P.; Wanichthanaolan, O.; Ramadoss, V.; Sim, B.; et al. The burden of alcohol and substance use disorders in adolescents and young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2025, 266, 112495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danpanichkul, P.; Ng, C.H.; Tan, D.J.H.; Wijarnpreecha, K.; Huang, D.Q.; Noureddin, M.; Young Alcohol Disease Collaborative. The Global Burden of Alcohol-associated Cirrhosis and Cancer in Young and Middle-aged Adults. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2024, 22, 1947–1949.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categorical Indicator | Level | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Race | White | 914 (71) |

| Black | 164 (13) | |

| Other | 137 (11) | |

| Unknown | 38 (2.9) | |

| Asian | 19 (1.5) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 19 (1.5) | |

| Other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.1) | |

| Ethnicity | Not Hispanic | 666 (52) |

| Hispanic | 600 (46) | |

| Unknown | 26 (2.0) | |

| Gender | Boy | 828 (64) |

| Girl | 424 (33) | |

| Transgender Girl | 11 (0.9) | |

| Non-Binary | 10 (0.8) | |

| Transgender Boy | 9 (0.7) | |

| Gender Fluid | 5 (0.4) | |

| Other | 4 (0.3) | |

| Agender | 1 (0.1) | |

| Insurance | Medicaid | 839 (65) |

| Commercial | 413 (32) | |

| Self-Pay | 20 (1.5) | |

| Special Billing | 11 (0.9) | |

| Financial Assistance | 8 (0.6) | |

| Worker’s Comp | 1 (0.1) | |

| Mental Health Diagnosis | Yes | 649 (50) |

| No | 643 (50) | |

| Court Involvement | Yes | 96 (7.0) |

| No | 1196 (93) | |

| Continuous Indicator | Mean ± SD | |

| Patient Age | 15.8 ± 1.5 | |

| Area Deprivation Index (ADI) State Decile Rank (1–10) | 5.2 ± 2.6 | |

| Binary Outcome * | Level | n (%) |

| Cannabis Use | Yes | 1047 (81) |

| No | 245 (19) | |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | Yes | 277 (21) |

| No | 1015 (79) | |

| Opioid Use Disorder | Yes | 196 (15) |

| No | 1096 (85) | |

| Multiple Substance Use | Yes | 426 (33) |

| No | 866 (67) | |

| Withdrawal Management Visits | Yes | 42 (3) |

| No | 1250 (97) | |

| Continuous Outcome † | Mean ± SD | |

| IOP Sessions Attended | 1.6 ± 6.6 | |

| STEP Sessions Attended | 19.5 ± 26.6 | |

| STEP Sessions Missed | 13.8 ± 16.0 | |

| Average Days Between Sessions | 13.9 ± 17.9 | |

| 30-Day Gaps Between Sessions | 1.0 ± 1.7 | |

| Inpatient Hospitalizations | 0.3 ± 0.9 | |

| Emergency Department Visits | 1.5 ± 3.0 | |

| Negative UDS | 0.4 ± 0.4 | |

| Negative UDS, Primary Substance | 0.5 ± 0.4 | |

| Model | Min. Class Size | Log Likelihood | AIC | BIC | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100% | −5371 | 10,759 | 10,799 | – |

| 2 | 30.4% | −5195 | 10,423 | 10,509 | 0.734 |

| 3 | 31.1% | −5157 | 10,367 | 10,498 | 0.623 |

| 4 | 17.7% | −5144 | 10,357 | 10,534 | 0.576 |

| 5 | 9.8% | −5134 | 10,355 | 10,577 | 0.674 |

| 6 | 6.7% | −5125 | 10,356 | 10,623 | 0.781 |

| 7 | 1.8% | −5116 | 10,356 | 10,669 | 0.709 |

| Analysis Outcome | p-Value (p < 0.05) | Effect Size (η2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANOVA Results for Continuous Outcomes | IOP Sessions Attended | 0.858 | <0.01 |

| Percent of STEP Sessions Attended | 0.002 | 0.02 | |

| Percent of STEP Sessions Missed | 0.002 | 0.02 | |

| Average Days Between Sessions | 0.419 | <0.01 | |

| 30-Day Gaps Between Sessions | 0.366 | <0.01 | |

| Inpatient Hospitalizations | 0.366 | <0.01 | |

| Emergency Department Visits | <0.001 | 0.03 | |

| Percent of Negative UDS | 0.014 | 0.02 | |

| Percent of Negative UDS for Primary Substance | 0.018 | 0.02 | |

| Logistic Regression Results for Categorical Outcomes | Opioid Use Disorder Diagnosis | 0.018 | 0.02 |

| Alcohol Use Disorder Diagnosis | 0.004 | 0.02 | |

| Cannabis Use Diagnosis | 0.170 | <0.01 | |

| Multiple Substance Diagnoses | 0.005 | 0.02 | |

| Withdrawal Management Visits | 0.377 | 0.02 | |

| Continuous Outcome | Comparison | Mean Diff (95% CI) | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of STEP Sessions Attended | Class 4-1 | 0.07 (0.02, 0.11) | <0.001 | The high access, sociocultural privilege class (Class 4) attended ~7% more sessions than the moderate access, low MH needs class (Class 1) |

| Class 4-2 | 0.04 (0.00, 0.08) | 0.039 | The high access, sociocultural privilege class (Class 4) attended ~4% more sessions than adolescents with moderate structural access and high MH needs (Class 2) | |

| Percent of STEP Sessions Missed | Class 4-1 | −0.07 (−0.11, −0.02) | <0.001 | The high access, sociocultural privilege class (Class 4) missed ~7% less sessions than the moderate access, low MH needs class (Class 1) |

| Class 4-2 | −0.04 (−0.08, −0.00) | 0.039 | The high access, sociocultural privilege class (Class 4) missed ~4% less sessions than adolescents with moderate structural access and high MH needs (Class 2) | |

| Emergency Department Visits After STEP Intake | Class 4-2 | −1.12 (−1.73, −0.51) | <0.001 | The high access, sociocultural privilege class (Class 4) had ~1.12 fewer ED visits than adolescents with moderate structural access and high MH needs (Class 2) |

| Class 5-4 | 1.42 (0.55, 2.29) | <0.001 | Adolescents with low access and high MH needs (Class 5) had ~1.42 more ED visits than the high access, sociocultural privilege class (Class 4) | |

| Percent of Negative UDSs | Class 4-3 | 0.17 (0.03, 0.31) | 0.0079 | The high access, sociocultural privilege class (Class 4) had ~17 percent more negative UDSs than the low access, court-involved class (Class 3) |

| Percent of Negative UDSs for Primary Substance | Class 4-3 | 0.19 (0.04, 0.34) | 0.0185 | The high access, sociocultural privilege class (Class 4) had ~19 percent more negative primary-SUD UDSs than the low access, court-involved class (Class 3) |

| Binary Outcome | Comparison | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | Interpretation |

| Opioid Use Disorder Diagnosis at Intake | Class 4-5 | 0.40 (0.18, 0.87) | 0.011 | The high access, sociocultural privilege class (Class 4) had 60% lower odds of OUD compared to adolescents with low access and high MH needs (Class 5) |

| Alcohol Use Disorder Diagnosis at Intake | Class 1-4 | 0.49 (0.28, 0.88) | 0.007 | The moderate access, low MH needs class (Class 1) had about half the odds of AUD compared to the high access, sociocultural privilege class (Class 4) |

| Multiple Substance Diagnoses at Intake | Class 1-4 | 0.57 (0.35, 0.94) | 0.019 | The moderate access, low MH needs class (Class 1) had ~43% lower odds of polysubstance use compared to the high access, sociocultural privilege class (Class 4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seely, H.D.; Still, L.; Weinberger, E.; Chen, E.; Holmes, K.; Loh, R.; Thurstone, C. Sociocultural Factors Impacting Substance Misuse and Treatment: A Latent Class Analysis of Youths Undergoing Combined Treatment. Future 2025, 3, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3040025

Seely HD, Still L, Weinberger E, Chen E, Holmes K, Loh R, Thurstone C. Sociocultural Factors Impacting Substance Misuse and Treatment: A Latent Class Analysis of Youths Undergoing Combined Treatment. Future. 2025; 3(4):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3040025

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeely, Hayley D., Luke Still, Emily Weinberger, Eileen Chen, Kalyn Holmes, Ryan Loh, and Christian Thurstone. 2025. "Sociocultural Factors Impacting Substance Misuse and Treatment: A Latent Class Analysis of Youths Undergoing Combined Treatment" Future 3, no. 4: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3040025

APA StyleSeely, H. D., Still, L., Weinberger, E., Chen, E., Holmes, K., Loh, R., & Thurstone, C. (2025). Sociocultural Factors Impacting Substance Misuse and Treatment: A Latent Class Analysis of Youths Undergoing Combined Treatment. Future, 3(4), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3040025