From Traditional Use to Molecular Mechanisms: A Bioinformatic and Pharmacological Review of the Genus Kalanchoe with In Silico Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

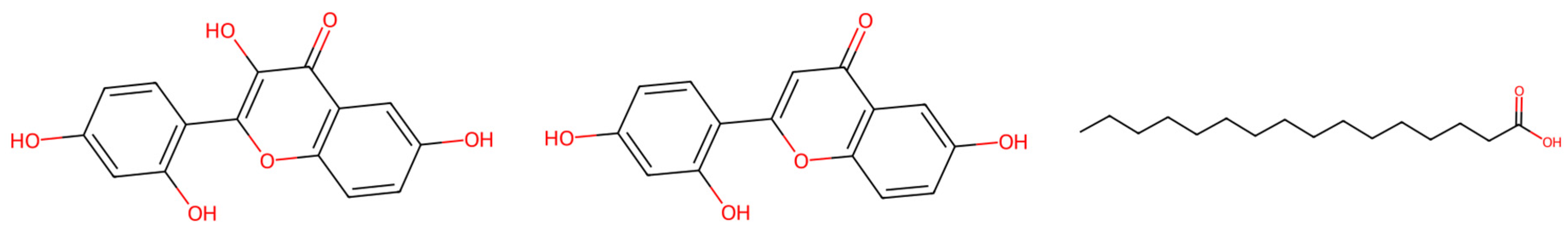

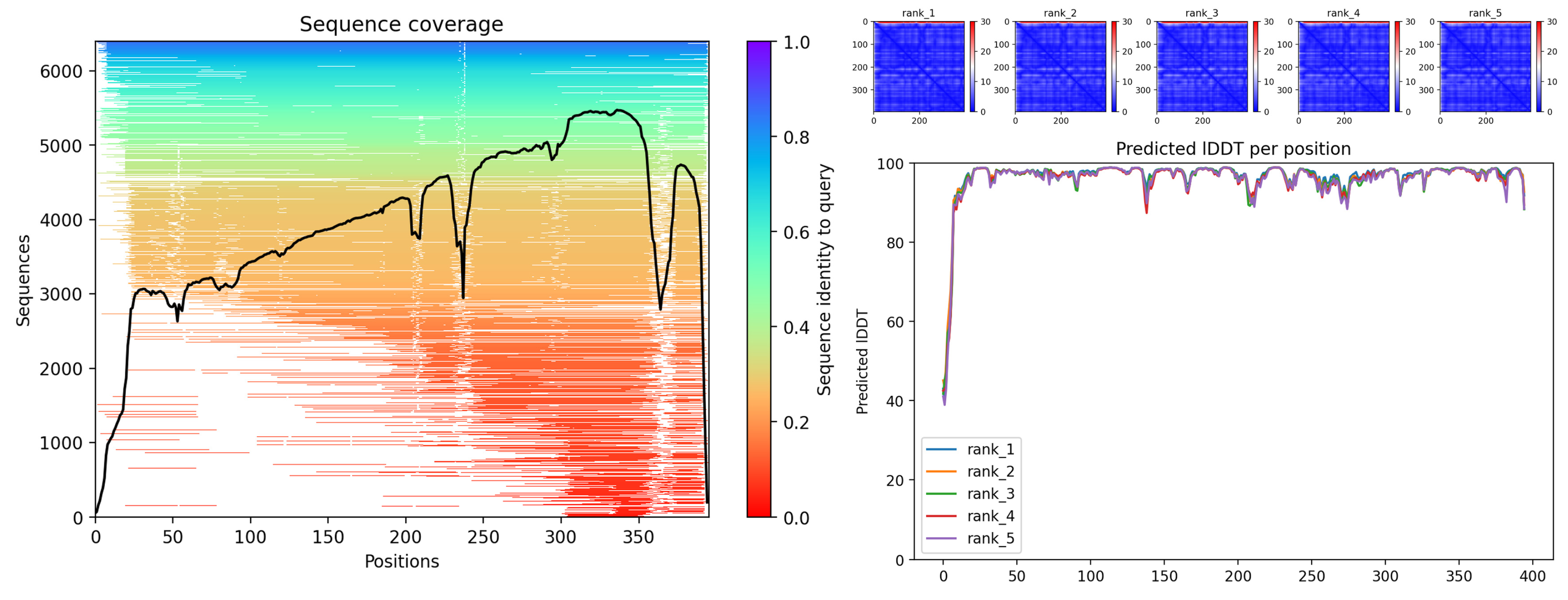

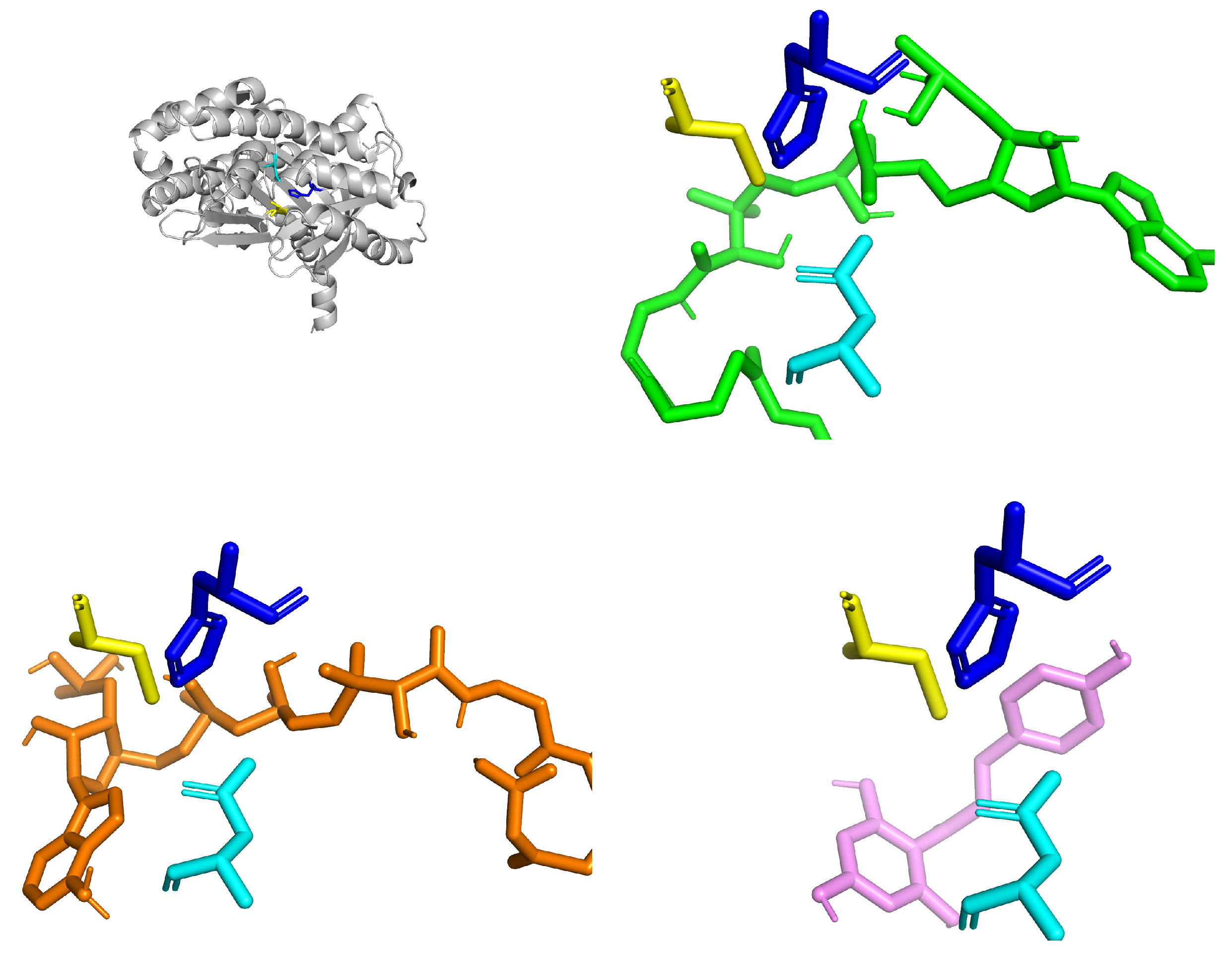

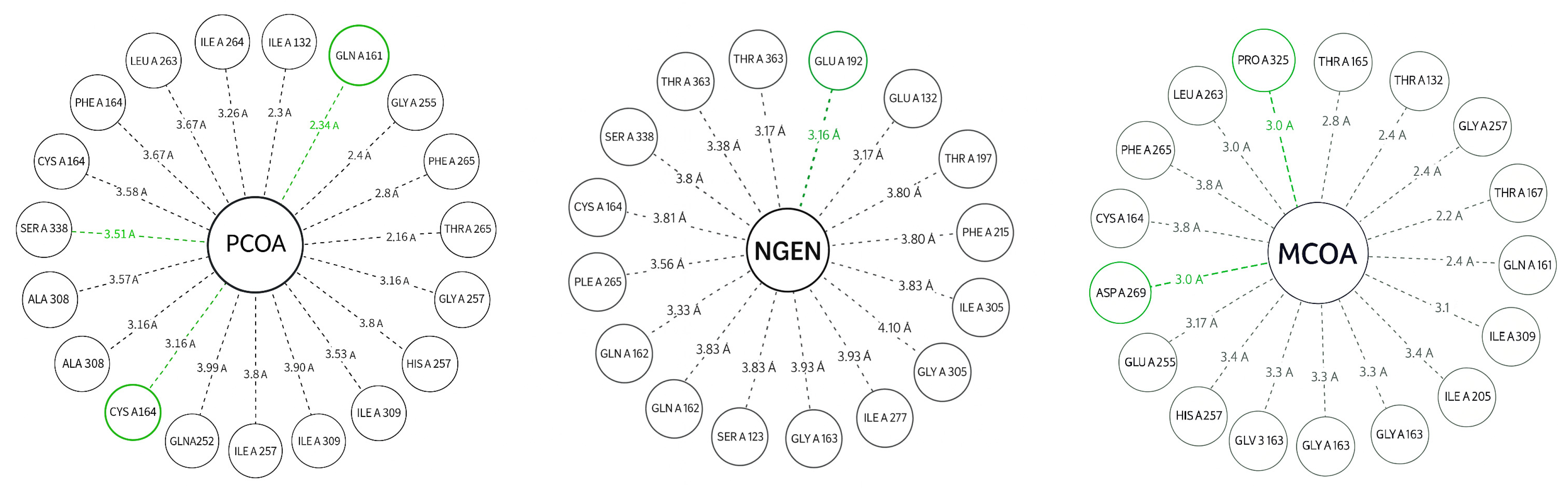

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Trials

3.2. Product List/Patent

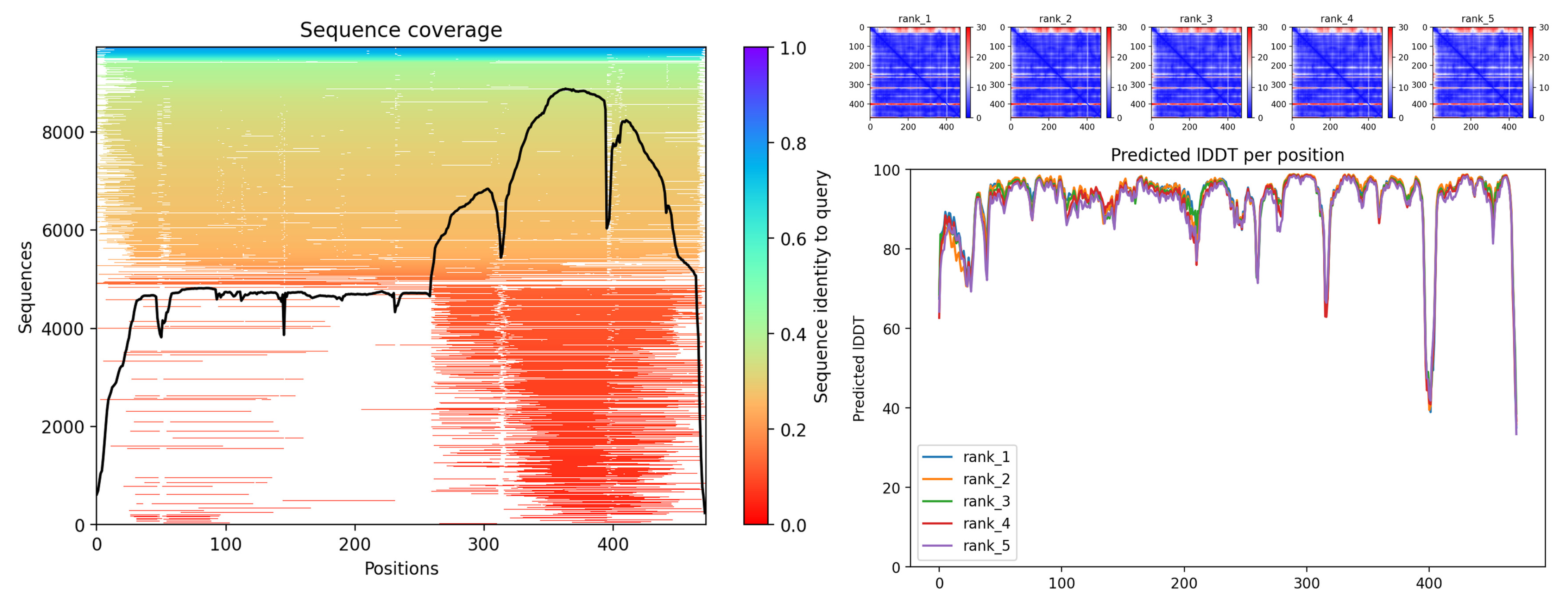

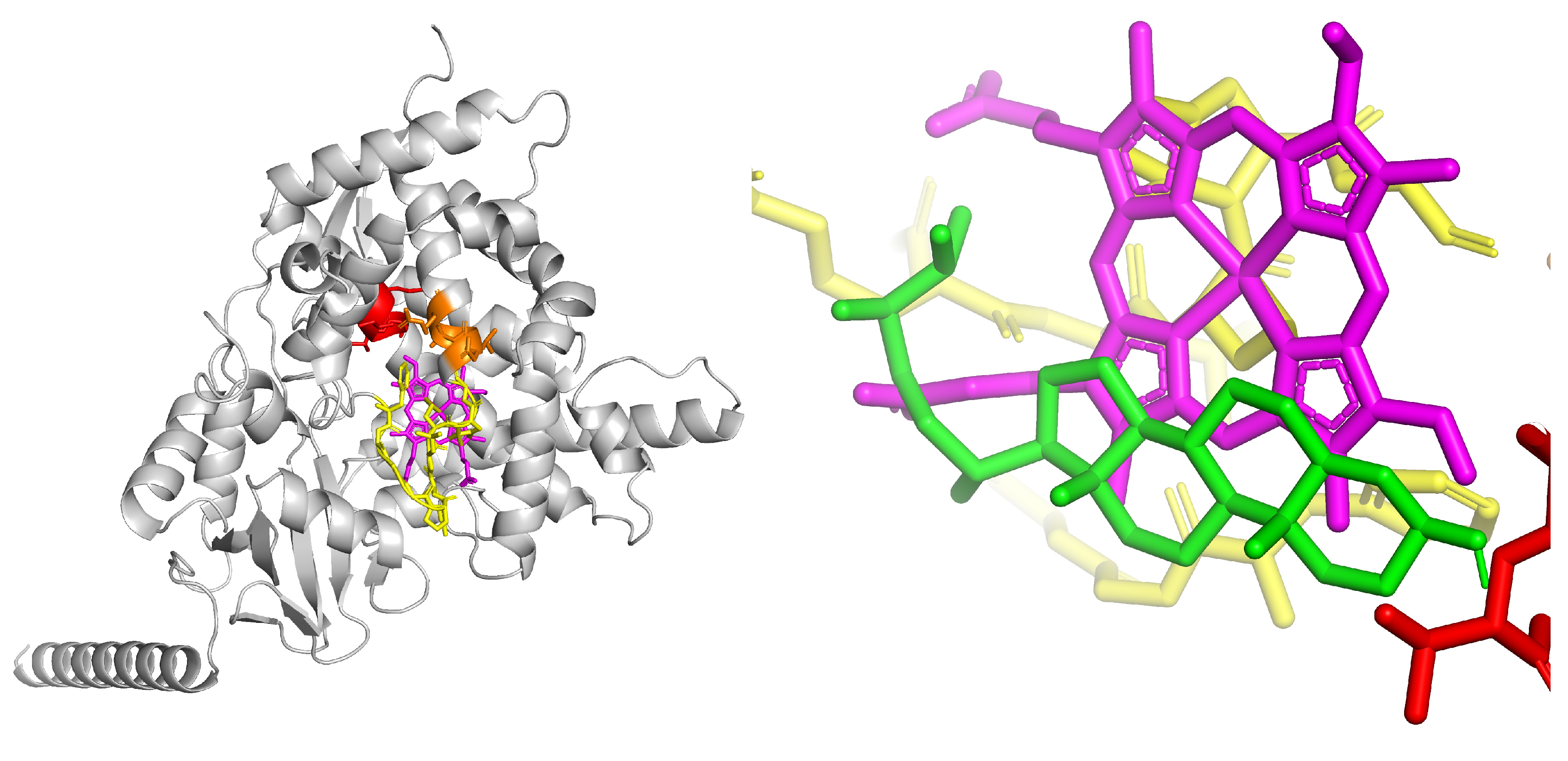

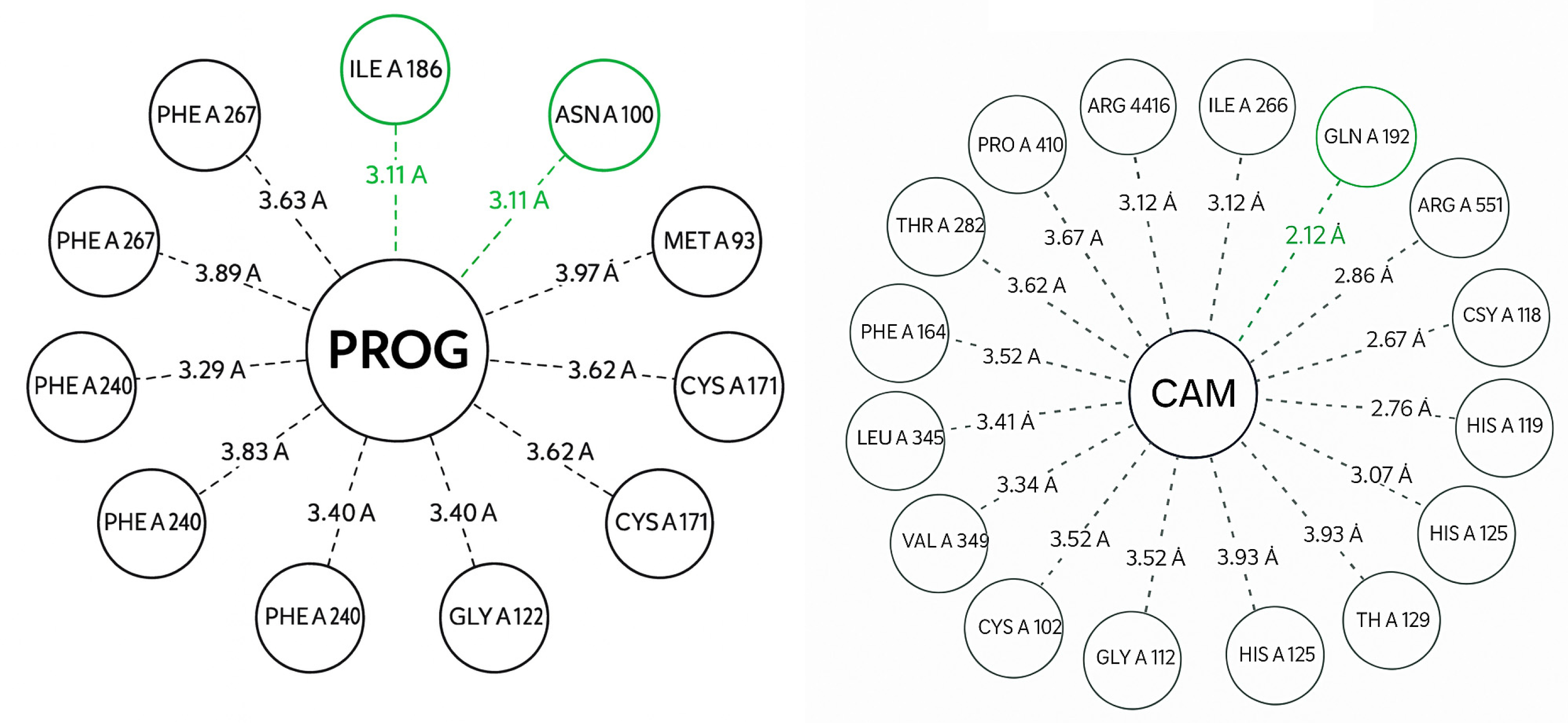

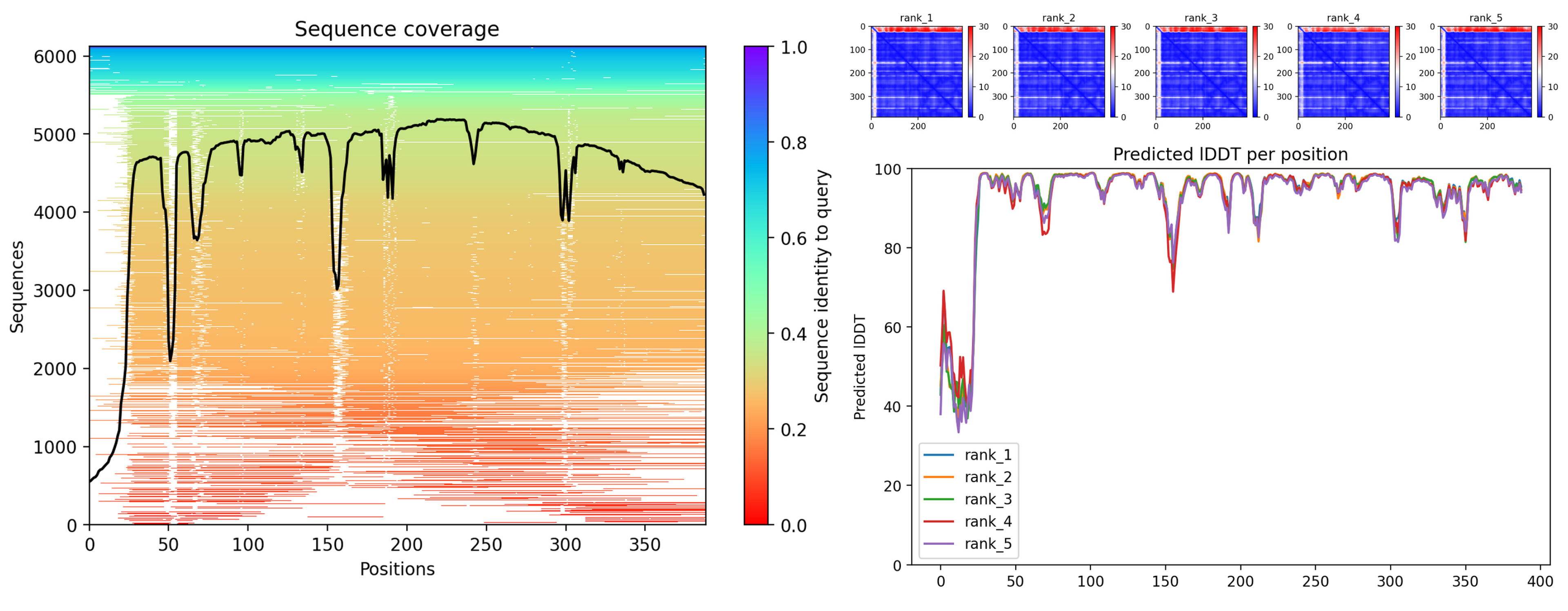

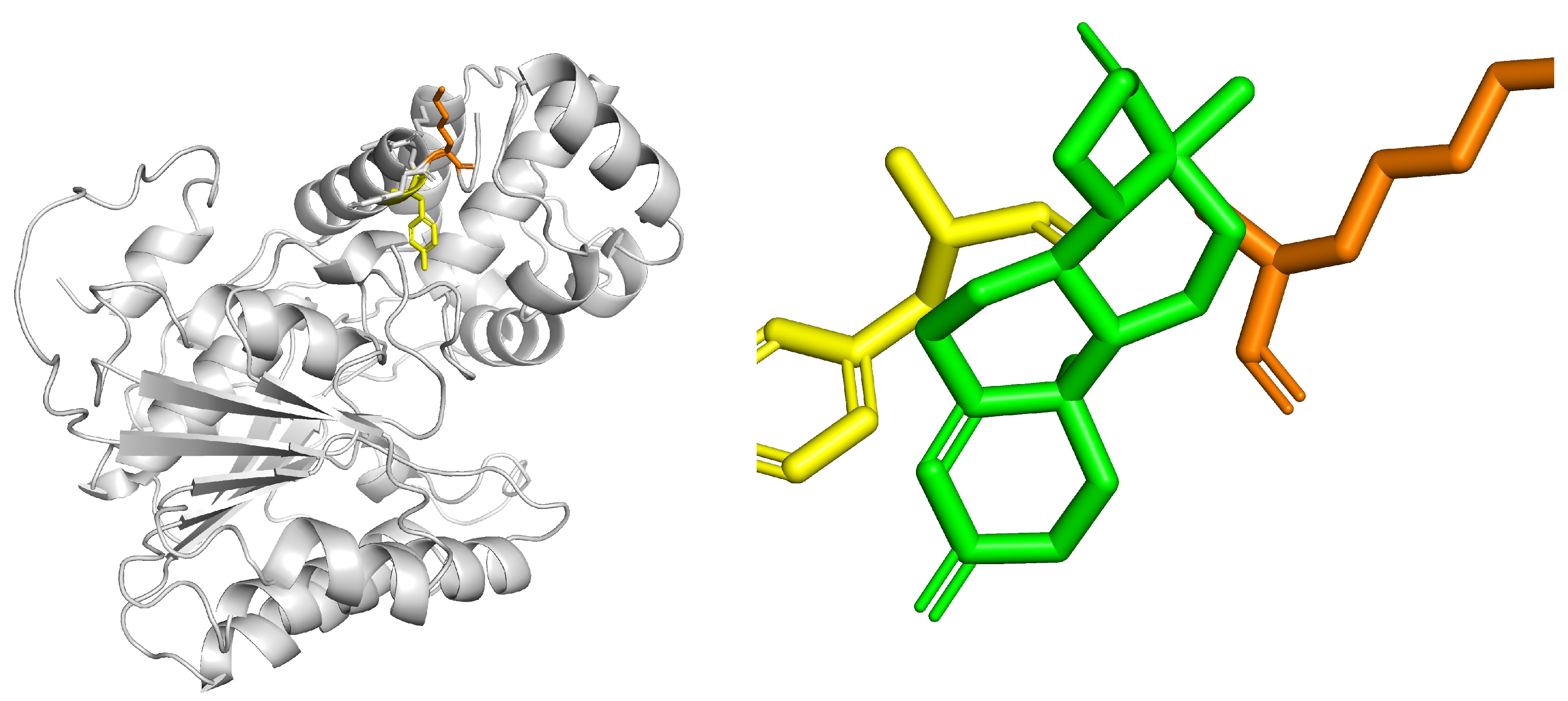

3.3. Bioinformatics Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allorge-Boiteau, L. Madagascar centre de speciation et d’origine du genre Kalanchoe (Crassulaceae). In Biogéographie de Madagascar; ORSTOM: Paris, France, 1996; pp. 137–145. ISBN 2-7099-1324-0. [Google Scholar]

- Asiedu-Gyekye, I.J.; Antwi, D.A.; Bugyei, K.A.; Awortwe, C. Comparative study of two Kalanchoe species: Total flavonoid and phenolic contents and antioxidant properties. Afr. J. Pure Appl. Chem. 2012, 6, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogucka-Kocka, A.; Zidorn, C.; Kasprzycka, M.; Szymczak, G.; Szewczyk, K. Phenolic acid content, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of four Kalanchoë species. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguelefack, T.B.; Nana, P.; Atsamo, A.D.; Dimo, T.; Watcho, P.; Dongmo, A.B.; Kamanyi, A. Analgesic and anticonvulsant effects of extracts from leaves of Kalanchoe crenata (Andrews) Haworth (Crassulaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 106, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richwagen, N.; Lyles, J.T.; Dale, B.L.; Quave, C.L. Antibacterial activity of Kalanchoe mortagei and K. fedtschenkoi against ESKAPE pathogens. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, E.; Villarreal, J.A.; Cantú, C.; Cabral, I.; Scott, L.; Yen, C. Ethnobotany in the Cumbres de Monterrey National Park, Nuevo León, México. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2007, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milad, R.; El-Ahmady, S.; Singab, A.N. Genus Kalanchoe (Crassulaceae): A review of its ethnomedicinal, botanical, chemical and pharmacological properties. Eur. J. Med. Plants 2014, 4, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Abdellaoui, S.; Destandau, E.; Toribio, A.; Elfakir, C.; Lafosse, M.; Renimel, I.; Landemarre, L. Bioactive molecules in Kalanchoe pinnata leaves: Extraction, purification, and identification. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 398, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S.C.; Balamurugan, V.; Elayaraja, R.; Prabakaran, A.S. Antioxidant and phytochemical potential of medicinal plant Kalanchoe pinnata. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2012, 3, 881. [Google Scholar]

- Supratman, U.; Fujita, T.; Akiyama, K.; Hayashi, H.; Murakami, A.; Sakai, H.; Ohigashi, H. Anti-tumor promoting activity of bufadienolides from Kalanchoe pinnata and K. daigremontiana × butiflora. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2001, 65, 947–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supratman, U.; Fujita, T.; Akiyama, K.; Hayashi, H. Insecticidal compounds from Kalanchoe daigremontiana × tubiflora. Phytochemistry 2001, 58, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowicz-Hajduk, J.; Hering, A.; Gucwa, M.; Hałasa, R.; Soluch, A.; Kowalczyk, M.; Ochocka, R. Biological activities of leaf extracts from selected Kalanchoe species and their relationship with bufadienolides content. Pharm. Biol. 2020, 58, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, E.A.; Reuter, S.; Martin, H.; Dehzad, N.; Muzitano, M.F.; Costa, S.S.; Taube, C. Kalanchoe pinnata inhibits mast cell activation and prevents allergic airway disease. Phytomedicine 2012, 19, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simberloff, D.; Von Holle, B. Positive interactions of nonindigenous species: Invasional meltdown? Biol. Invasions 1999, 1, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhymer, J.M.; Simberloff, D. Extinction by hybridization and introgression. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1996, 27, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxcroft, L.C.; Pyšek, P.; Richardson, D.M.; Genovesi, P.; MacFadyen, S. Plant invasion science in protected areas: Progress and priorities. Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 1353–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayers, E.W.; Beck, J.; Bolton, E.E.; Brister, J.R.; Chan, J.; Comeau, D.C.; Connor, R.; DiCuccio, M.; Farrell, C.M.; Feldgarden, M.; et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D23–D44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hu, R.; Yin, H.; Jenkins, J.; Shu, S.; Tang, H.; Liu, D.; Weighill, D.A.; Yim, W.C.; Ha, J.; et al. The Kalanchoë genome provides insights into convergent evolution and building blocks of crassulacean acid metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanke, M.; Morgenstern, B. AUGUSTUS: A web server for gene prediction in eukaryotes that allows user-defined constraints. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, W465–W467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: Making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrödinger, L.L.C. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System; Version 2.5; Schrödinger LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Forli, S.; Olson, A.J. Meeko: A Preparation Tool for AutoDock Molecular Docking. GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/forlilab/meeko (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- O’Boyle, N.M.; Banck, M.; James, C.A.; Morley, C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Hutchison, G.R. Open Babel: An open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminformatics 2011, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Python Software Foundation. Python: A Dynamic, Open Source Programming Language (Version 3.10). Available online: https://www.python.org (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Microsoft Corporation. Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL); Version 2; Microsoft: Redmond, WA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://learn.microsoft.com/windows/wsl/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W. Data structures for statistical computing in Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference (SciPy), Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R.A.; Swindells, M.B. LigPlot+: Multiple ligand–protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011, 51, 2778–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIOVIA; Dassault Systèmes. Discovery Studio Visualizer; Version 20.1.0.19295; Dassault Systèmes: San Diego, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, N.P.; Dixit, V.K. Hepatoprotective activity of leaves of Kalanchoe pinnata Pers. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 86, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzitano, M.F.; Tinoco, L.W.; Guette, C.; Kaiser, C.R.; Rossi-Bergmann, B.; Costa, S.S. The antileishmanial activity assessment of unusual flavonoids from Kalanchoe pinnata. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 2071–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlalka, G.V.; Patil, C.R.; Patil, M.R. Protective effect of Kalanchoe pinnata Pers. (Crassulaceae) on gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2007, 39, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madariaga-Navarrete, A.; Aquino-Torres, E.; Cariño-Cortés, R.; Villagómez-Ibarra, R.; Ocampo-López, J.; Sharma, A.; Hernández-Fuentes, A.D. Kalanchoe daigremontiana: Functional Properties and Histopathological Effects on Wistar Rats Under Hyperglycemia-Inducing Diet. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2021, 55, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimo, T.; Fotio, A.L.; Nguelefack, T.B.; Asongalem, E.A.; Kamtchouing, P. Antiinflammatory activity of leaf extracts of Kalanchoe crenata Andr. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2006, 38, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, E.R.D.; Félix-Silva, J.; Xavier-Santos, J.B.; Fernandes, J.M.; Guerra, G.C.B.; de Araújo, A.A.; Zucolotto, S.M. Local anti-inflammatory activity: Topical formulation containing Kalanchoe brasiliensis and Kalanchoe pinnata leaf aqueous extract. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 113, 108721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Z.R.; Ho, Y.L.; Huang, S.C.; Huang, T.H.; Lai, S.C.; Tsai, J.C.; Chang, Y.S. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative activities of Kalanchoe gracilis (L.) DC stem. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2011, 39, 1275–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Z.R.; Peng, W.H.; Ho, Y.L.; Huang, S.C.; Huang, T.H.; Lai, S.C.; Chang, Y.S. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of the methanol extract of Kalanchoe gracilis (L.) DC stem in mice. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2010, 38, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supratman, U.; Fujita, T.; Akiyama, K.; Hayashi, H. New insecticidal bufadienolide, bryophyllin C, from Kalanchoe pinnata. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2000, 64, 1310–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryer, M.; Lane, K.; Greer, M.; Cates, R.; Burt, S.; Andrus, M.; Johnson, F.B. Isolation and identification of compounds from Kalanchoe pinnata having human alphaherpesvirus and vaccinia virus antiviral activity. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 1586–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisyah, L.S.; Yun, Y.F.; Herlina, T.; Julaeha, E.; Zainuddin, A.; Nurfarida, I.; Shiono, Y. Flavonoid compounds from the leaves of Kalanchoe prolifera and their cytotoxic activity against P-388 murine leukemia cells. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2017, 23, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, J.; Nowak, P.; Wachowicz, B.; Piechocka, J.; Głowacki, R.; Moniuszko-Szajwaj, B.; Stochmal, A. Antioxidant efficacy of Kalanchoe daigremontiana bufadienolide-rich fraction in blood plasma in vitro. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 3182–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.C.; Huang, G.J.; Liaw, C.C.; Yang, C.S.; Yang, C.P.; Kuo, C.L.; Kuo, Y.H. A new megastigmane from Kalanchoe tubiflora (Harvey) Hamet. Phytochem. Lett. 2013, 6, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaly, N.S.; Mina, S.A.; Abdel-Aziz, N.F.; Sammour, E.A. Insecticidal activity of the main flavonoids from the leaves of Kalanchoe beharensis and Kalanchoe longiflora. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 7, 196–202. [Google Scholar]

- Bopda, O.S.M.; Longo, F.; Bella, T.N.; Edzah, P.M.O.; Taïwe, G.S.; Bilanda, D.C.; Dimo, T. Antihypertensive activities of the aqueous extract of Kalanchoe pinnata (Crassulaceae) in high salt-loaded rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.B.; Dongare, V.R.; Kulkarni, C.R.; Joglekar, M.M.; Arvindekar, A.U. Antidiabetic activity of Kalanchoe pinnata in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats by glucose independent insulin secretagogue action. Pharm. Biol. 2013, 51, 1411–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, C.; Hartati, S.R.I.; Santi, M.R.; Firdaus, R.; Hanafi, M.; Kardono, L.B.; Hotta, H. Isolation and identification of substances with anti-hepatitis C virus activities from Kalanchoe pinnata. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Huang, S.C.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, Z.R.; Kung, S.H.; Chang, Y.S.; Lin, C.W. Antiviral ability of Kalanchoe gracilis leaf extract against enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A16. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 503165. [Google Scholar]

- Ibitoye, O.B.; Olofinsan, K.A.; Teralı, K.; Ghali, U.M.; Ajiboye, T.O. Bioactivity-guided isolation of antidiabetic principles from the methanolic leaf extract of Bryophyllum pinnatum. J. Food Biochem. 2018, 42, e12627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majaz, Q.A.; Nazim, S.; Afsar, S.; Siraj, S.; Siddik, P.M. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of roots of Kalanchoe pinnata. Int. J. Pharmacol. Biol. Sci. 2011, 5, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, E.A.; Da-Silva, S.A.G.; Muzitano, M.F.; Silva, P.M.R.; Costa, S.S.; Rossi-Bergmann, B. Immunomodulatory pretreatment with Kalanchoe pinnata extract and its quercitrin flavonoid effectively protects mice against fatal anaphylactic shock. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2008, 8, 1616–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.S.; Souza, M.D.L.M.D.; Ibrahim, T.; Melo, G.O.D.; Almeida, A.P.D.; Guette, C.; Koatz, V.L.G. Kalanchosine dimalate, an anti-inflammatory salt from Kalanchoe brasiliensis. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 815–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ürményi, F.G.G.; Saraiva, G.D.N.; Casanova, L.M.; Matos, A.D.S.; de Magalhães Camargo, L.M.; Romanos, M.T.V.; Costa, S.S. Anti-HSV-1 and HSV-2 flavonoids and a new kaempferol triglycoside from the medicinal plant Kalanchoe daigremontiana. Chem. Biodivers. 2016, 13, 1707–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowicz-Hajduk, J.; Asztemborska, M.; Krauze-Baranowska, M.; Godlewska, S.; Gucwa, M.; Moniuszko-Szajwaj, B.; Ochocka, J.R. Identification of flavonoids and bufadienolides and cytotoxic effects of Kalanchoe daigremontiana extracts on human cancer cell lines. Planta Med. 2020, 86, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowicz-Hajduk, J.; Gucwa, M.; Hajduk, A.; Ochocka, J.R. Kalanchoe blossfeldiana extract induces cell cycle arrest and necrosis in human cervical cancer cells. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2019, 15, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.; Mondal, C.; Bera, R.; Chakraborty, S.; Barik, R.; Roy, P.; Sen, T. Antimicrobial properties of Kalanchoe blossfeldiana: A focus on drug resistance with particular reference to quorum sensing-mediated bacterial biofilm formation. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 67, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, R.T.; Coutinho, M.A.S.; Malvar, D.D.C.; Costa, E.A.; Florentino, I.F.; Costa, S.S.; Vanderlinde, F.A. Mechanisms underlying the antinociceptive, antiedematogenic, and anti-inflammatory activity of the main flavonoid from Kalanchoe pinnata. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 429256. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo, A.; Casanova, L.M.; Corrêa, M.F.P.; Da Costa, N.M.; Nasciutti, L.E.; Costa, S.S. Potential therapeutic effects of underground parts of Kalanchoe gastonis-bonnieri on benign prostatic hyperplasia. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 6340757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Manitius, S.; Flügel, D.; Steinlein, B.G.; Schnelle, M.; von Mandach, U.; Simões-Wüst, A.P. Bryophyllum pinnatum in the treatment of restless legs syndrome: A case series documented with polysomnography. Clin. Case Rep. 2019, 7, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-González, I.; García-Carrancá, A.M.; Cornejo-Garrido, J.; Ordaz-Pichardo, C. Cytotoxic effect of Kalanchoe flammea and induction of intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic signaling in prostate cancer cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 222, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical Trials. From the U.S. National Library of Medicine. Bryophyllum spp. 2021. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=Kalanchoe (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Simões-Wüst, A.P.; Lapaire, O.; Hösli, I.; Wächter, R.; Fürer, K.; Schnelle, M.; von Mandach, U. Two randomised clinical trials on the use of Bryophyllum pinnatum in preterm labour: Results after early discontinuation. Complement. Med. Res. 2018, 25, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrigger-Steiner, C.; Simões-Wüst, A.P.; Kuck, A.; Fürer, K.; Hamburger, M.; von Mandach, U. Sleep quality in pregnancy during treatment with Bryophyllum pinnatum: An observational study. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betschart, C.; von Mandach, U.; Seifert, B.; Scheiner, D.; Perucchini, D.; Fink, D.; Geissbühler, V. Randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial with Bryophyllum pinnatum versus placebo for the treatment of overactive bladder in postmenopausal women. Phytomedicine 2013, 20, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.-H.; Shin, D.-G. Liquid-Phase Antioxidant Composition Comprising Kalanchoe Extract for After-Treatment Following Photodynamic Therapy. WO-2015002347-A1, 2 July 2013. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/WO-2015002347-A1 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Sylwia, N. Skin Care Composition. US-2020276256-A1, 28 April 2017. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/US-2020276256-A1 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Kim, D.-W.; Park, J.-H.; Chung, K.-S.; Kim, D.-Y.; Choi, G.-I. Cosmetic Composition Containing Kalanchoe gastonis and Process for Preparation Thereof. KR-20140079896-A, 20 December 2012. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/KR-20140079896-A (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Seo, J.-H.; Shin, D.-G. Antioxidizing Liquid Composition Including Kalanchoe Gastonis-Bonnieri Extract for Photodynamic Therapy Post Treatment. KR-20150004092-A, 2 July 2013. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/KR-20150004092-A (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Pichardo-Ordaz, C.; González-Arias, I. Kalanchoe flammea Extract with Ethyl Acetate, the Fractions and Major Compounds Thereof for the Treatment of Prostate Cancer. MX-2014015323-A, 15 December 2014. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/MX-2014015323-A (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Zakharchenko-Sergeevna, N.; Buryanov-Ivanovich, Y. Method for Antimicrobial Peptide Cecropin p1 Production from Pinnated Kalanchoe Transgenic Plants Extract. RU-2632116-C1, 2 October 2017. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU2632116C1/en?q=(Method+for+Antimicrobial+Peptide+Cecropin+p1+Production+Pinnated+Kalanchoe+Transgenic+Plants+Extract)&oq=Method+for+Antimicrobial+Peptide+Cecropin+p1+Production+from+Pinnated+Kalanchoe+Transgenic+Plants+Extract (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Lefeuvre, L. Cosmetic or Dermatological Composition Based on Kalanchoe linearifolia Plant Extracts. EP-1857099-A1, 10 May 2006. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/EP-1857099-A1 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Arantes-Ostrosky, E.; Azevedo De Brito-Damasceno, A.; Morais-Fernandes, J.; Ferrari, M.; De Oliveira-Rodrigues, B.; Zucolotto-Langassner, S.M.; Andrade Gomes-Barreto, E. Cosmetic Compositions Containing Kalanchoe brasiliensis and Its Use as a Hydrating Product. BR-102015032217-A2, 22 December 2015. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/BR102015032217B1/en?q=(.+Cosmetic+Compositions+Containing+Kalanchoe+brasiliensis+and+Its+Use+Hydrating+Product.)&oq=.+Cosmetic+Compositions+Containing+Kalanchoe+brasiliensis+and+Its+Use+as+a+Hydrating+Product (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Lefeuvre, L. Topical Composition, Useful e.g., to Prevent/Treat Cutaneous Hypersensibility and Skin Aging and in Skin Repairing, Comprises Kalanchoe linearifolia Extract as Active Ingredient. FR-2900821-A1, 10 May 2006. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/FR-2900821-A1 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Lee, J.-S.; Ahn, T.-H. Manufacturing Method for Antioxidant Composition by Using Kalanchoe Gastonis-Bonnieri Leaf Extract. KR-20140142531-A, 4 June 2013. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/KR-20140142531-A (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Courtin, O. Composition, Useful for Promoting Collagen Synthesis, Protecting Skin Protein Glycation and Limiting the Excessive Production of Matrix Metalloproteinases, Comprises Aqueous and/or Alcoholic Extract of Kalanchoe pinnata. FR-3000390-A1, 28 December 2012. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/FR-3000390-A1 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Seo, J.-H.; Shin, D.-G. Composition Including Kalanchoe Gastonis-Bonnieri Extract Using Iontophoresis. KR-20150047040-A, 23 October 2013. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/KR-20150047040-A (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Lei, Z.; Wei, Y.; Xiaolu, B.; Yue, Y.; Xingjun, T.; Ling, L.; Jingyi, H.; Xia, W.; Jing, Z.; Xingping, L.; et al. Application of Bryophyllum, Extract and Medicinal Preparation of Bryophyllum. CN-104107209-A, 1 August 2014. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/CN-104107209-A (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Lee, C.-Y. Preparation of Chinese Herbal Composite Recipe Used in Environmental Sanitation. US-2005158402-A1, 20 January 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/US-2005158402-A1 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Santy, K.; Ravindranath, A. Herbal Composition for the Treatment of Burns. WO-2020201847-A1, 29 March 2019. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/patent/WO-2020201847-A1 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- García-Pérez, P.; Barreal, M.E.; Rojo-De Dios, L.; Cameselle-Teijeiro, J.F.; Gallego, P.P. Bioactive natural products from the genus Kalanchoe as cancer chemopreventive agents: A review. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2019, 61, 49–84. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, H.; Shanmugam, V.K. Anti-inflammatory activity screening of Kalanchoe pinnata methanol extract and its validation using a computational simulation approach. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2019, 14, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiana, K.A.; Mary, K.L.; Esther, A.A. Phytochemical, antioxidant and antimicrobial evaluation of Nigerian Kalanchoe pinnata (Lam.). J. Chem. Soc. Niger. 2019, 44, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, J.; Stochmal, A. Bufadienolides of Kalanchoe species: An overview of chemical structure, biological activity and prospects for pharmacological use. Phytochem. Rev. 2017, 16, 1155–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra-García, A.; Golubov, J.; Mandujano, M.C. Invasion of Kalanchoe by clonal spread. Biol. Invasions 2015, 17, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Guillot, D.; Ren, M.X.; López-Pujol, J. Kalanchoe (Crassulaceae) as invasive aliens in China–new records, and actual and potential distribution. Nord. J. Bot. 2016, 34, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenti, E.; Simonetti, G.; Bochicchio, M.T.; Martinelli, G. Main changes in European clinical trials regulation (No 536/2014). Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2018, 11, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, A.D.; Conway, D.I.; MacDonald, T.M.; McInnes, G.T. The unintended consequences of clinical trials regulations. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-González, C.R.; Madariaga-Navarrete, A.; Fernández-Cortés, J.M.; Islas-Pelcastre, M.; Oza, G.; Iqbal, H.; Sharma, A. Advances and Applications of Water Phytoremediation: A Potential Biotechnological Approach for the Treatment of Heavy Metals from Contaminated Water. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.K.; Illangasekare, S.; Weaver, M.A.; Leonard, D.G.; Merz, J.F. Effects of patents and licenses on the provision of clinical genetic testing services. J. Mol. Diagn. 2003, 5, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinneny, J.R.; Benfey, P.N. Studying root development using a genomic approach. Annu. Plant Rev. 2010, 37, 325. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, C.; Guo, L.; Hu, R.; Huang, C.; Guo, X. Antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects of vitamin C on the liver of laying hens under chronic heat stress. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1052553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, Q.; Shen, W.; El Mohtar, C.A.; Zhao, X.; Gmitter, F.G., Jr. Functional study of CHS gene family members in citrus revealed a novel CHS gene affecting the production of flavonoids. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, T.; Krüerke, D.; Simões-Wüst, A.P. How physicians and nursing staff perceive effectiveness and tolerability of Bryophyllum preparations: An online survey in an anthroposophic hospital. Complement. Med. Res. 2024, 31, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Song, H.; Deng, X.; Yang, M. Genome-wide identification of CYP90 family and functional analysis of NnCYP90B1 on rhizome enlargement in lotus. Veg. Res. 2024, 4, e035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enoki, S.; Tanaka, K.; Moriyama, A.; Hanya, N.; Mikami, N.; Suzuki, S. Grape cytochrome P450 CYP90D1 regulates brassinosteroid biosynthesis and increases vegetative growth. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 196, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.T.; Fujioka, S.; Kozuka, T.; Tax, F.E.; Takatsuto, S.; Yoshida, S.; Tsukaya, H. CYP90C1 and CYP90D1 are involved in different steps in the brassinosteroid biosynthesis pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2005, 41, 710–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.B.D.S.; Casanova, L.M.; Costa, S.S. Bioactive compounds from Kalanchoe genus potentially useful for the development of new drugs. Life 2023, 13, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Ernst, M.; Christmann, A.; Tropper, M.; Leykauf, T.; Kreis, W.; Munkert, J. Knockout of Arabidopsis thaliana VEP1, encoding a PRISE (Progesterone 5β-Reductase/Iridoid Synthase-Like Enzyme), leads to metabolic changes in response to exogenous methyl vinyl ketone (MVK). Metabolites 2021, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhika, R.; Suradi, S.; Sutanto, Y.S. The Effect of Roflumilast on Absolute Neutrophil Count, MMP-9 Serum, %VEP1 Value, and CAT Scores in Stable COPD Patients. J. Respirologi Indones. 2022, 42, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specie | Extract/Compound | Property | Organism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K. pinnata | Leaf juice concentrate | Hepatoprotective activity | Wistar rats | [33] |

| K. pinnata | Kaempferol and derivates | Antileishmanial activity | Leishmania amazonenis amastigotes | [34] |

| K. daigremontiana | Bufadienolides | Insecticidal activity | Bombyx mori larvae | [11] |

| K. pinnata | Bufadienolides | Anti-tumor-promoting activity | Raji cells | [10] |

| K. daigremontiana | Bufadienolides | Anti-tumor-promoting activity | Raji cells | [11] |

| K. pinnata | Aqueous leaf extract | Nephroprotective and antioxidant activity | Wistar rats | [35] |

| K. daigremontiana | Crude leaf extract | Hepatoprotective activity in diabetes | Wistar rats | [36] |

| K. crenata | Leaf extract | Anti-inflammatory and anti-arthritic activity | Wistar rats | [37] |

| K. brasiliensis | Aqueous leaf extract | Local anti-inflammatory activity | Swiss albino mice | [38] |

| K. pinnata | Aqueous leaf extract | Local anti-inflammatory activity | Swiss albino mice | [38] |

| K. gracilis | Methanolic stem extract | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiproliferative activities | Murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 and HepG2 | [39] |

| K. gracilis | Methanolic stem extract | Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities | ICR mice | [40] |

| K. pinnata | Bryophilline A and C | Insecticidal activity against third-instar larvae | Silkworm (Bombyx mori) | [41] |

| K. pinnata | KPB-100 and KPB-200 | Virus inhibitors | HHV-2 and VACV | [42] |

| K. prolifera | Kaempferol and quercetin derivates | Cytotoxic activity | P-388 murine leukemia cells | [43] |

| K. daigremontiana | 11α,19-dihydroxytelocinobufagin, bersaldegenin-1-acetate, and other bersaldegenin derivates | Antioxidant activity | Blood plasma | [44] |

| K. tubiflora | (6S,7R,8R,9S)-6-oxaspiro-7,8-dihydroxymegastigman-4-en-3-one | Anti-inflammatory activities | Murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 | [45] |

| K. beharensis | Methanol extract of K. beharensis | Insecticidal activity | Spodoptera littoralis | [46] |

| K. longiflora | Methanol extract of K. longiflora | Insecticidal activity | Spodoptera littoralis | [46] |

| K. pinnata | Aqueous extract | Antihypertensive activities | High-salt-loaded rats (SHR) | [47] |

| K. fedtschenkoi | Quercetin and caffeic acid | Antibacterial activity | ESKAPE pathogens | [5] |

| K. mortagei | Quercetin and caffeic acid | Antibacterial activity | ESKAPE pathogens | [5] |

| K. pinnata | Steam distillate of leaves | Antidiabetic activity | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats | [48] |

| K. pinnata | Quercetin, gallic acid, and quercitrin | Antiviral activity | Huh7it-1 cells | [49] |

| K. gracilis | Quercetin, gallic acid, and quercitrin | Antiviral activity | Enterovirus 71 (EV71) and coxsackievirus A16 (CVA16) | [50] |

| B. pinnatum | Ethylacetate fraction of the partitioned methanolic extract | Antidiabetic activity | Alloxan-induced diabetic rats | [51] |

| K. pinnata | Methanolic extract of roots | Antibacterial activity | Escherichia coli Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa | [52] |

| K. pinnata | Aqueous extract and quercitrin | Antiallergic activity | Male BALB/c mice | [53] |

| K. brasiliensis | 3,6-diamino-4,5-dihydroxyoctanedioic acid | Anti-inflammatory activity | Male C57B110 mice | [54] |

| K. daigremontiana | Kaempferol and derivates | Antiviral activity | Acyclovir-sensitive strains of HSV-1 and HSV-2 | [55] |

| K. daigremontiana | Dichloromethane fraction of the ethanol extract | Cytotoxic activity | HeLa, SKOV-3, MCF-7, A375 cell lines | [56] |

| K. blossfeldiana | Ethanolic extract of leaves | Cytotoxic activity | HeLa cell line | [57] |

| K. blossfeldiana | Methanol extract | Antimicrobial activity | Diverse pathogenic bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, among others | [58] |

| K. pinnata | Aqueous extract | Antinociceptive, antiedematogenic, and anti-inflammatory activities | Male Swiss mice | [59] |

| K. gastonis-bonnieri | Aqueous extract | Cytotoxic activity | Stromal cells from primary benign prostatic hyperplasia | [60] |

| B. pinnatum | Chewable tablets (100 mg dried BP matter in 1 g) | sedative and spasmolytic activity | Patients with restless leg syndrome | [61] |

| K. flammea | F82-P2 fraction of the extract, rich in coumaric acid and palmitic acid | Cytotoxic activity | PC-3 cells | [62] |

| Status | Study Title | Conditions | Interventions | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not yet recruiting | Perceived Changes in Anxiety Symptom Burden During Treatment With Bryophyllum Pinnatum | Anxiety Symptoms | Drug: Bryophyllum 50%; chewing tablets | Unknown |

| Recruiting | Effectiveness of Bryophyllum in Nocturia-Therapy | Nocturia, Sleep Disorder | Drug: Bryophyllum pinnatum 50%; tablets into capsules (verum: 2 × 2 capsules/day) | University of Hospital, Clinic for Gynecology, Zurich, Switzerland |

| Completed | Bryophyllum Versus Placebo for Overactive Bladder | Overactive Bladder | Drug: Bryophyllum pinnatum; placebo in form of lactose | Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Zurich, Switzerland |

| Terminated | Bryophyllum Pinnatum Versus Solifenacin Versus Placebo for Overactive Bladder | Overactive Bladder, Urge Urinary Incontinence | Drug: Bryophyllum | Gynecologic Department, University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland |

| Unknown † | Bryophyllum vs. Nifedipine | Tocolysis | Drug: Bryophyllum p. | Department of Obstetrics, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland |

| Completed | The Impact of Bryophyllum on Preterm Delivery | Preterm Delivery, Preterm Contractions, Cervical Shortening | Drug: Bryophyllum; Other: Placebo | Obstetrical Unit, Women’s University Hospital Basel, Basel, Basel Stadt, Switzerland |

| Plant Species | Patent | Patent Number | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kalanchoe sp. | Antioxidant composition | WO-2015002347-A1 | [67] |

| Kalanchoe pinnata, Kalanchoe daigremontiana | Skin care composition | US-2020276256-A1 | [68] |

| Kalanchoe gastonis | Cosmetic composition | KR-20140079896-A | [69] |

| Kalanchoe Gastonis-Bonnieri | Liquid composition for photodynamic therapy post treatment | KR-20150004092-A | [70] |

| Kalanchoe flammea | Extract with ethyl acetate for the treatment of prostate cancer | MX-2014015323-A | [71] |

| Kalanchoe pinnata | Method for antimicrobial peptide production | RU-2632116-C1 | [72] |

| Kalanchoe linearifolia | Dermatological composition | EP-1857099-A1 | [73] |

| Kalanchoe brasilensis | Cosmetic composition | BR-102015032217-A2 | [74] |

| Kalanchoe linearifolia | Topical composition | FR-2900821-A1 | [75] |

| Kalanchoe Gastonis-Bonnieri | Manufacturing method for antioxidant composition | KR-20140142531-A | [76] |

| Kalanchoe pinnata | Composition for skin care and protection | FR-3000390-A1 | [77] |

| Kalanchoe Gastonis-Bonnieri | Composition using iontophoresis | KR-20150047040-A | [78] |

| Bryophyllum sp. | Medicinal preparation | CN-104107209-A | [79] |

| Bryophyllum pinnatum | Preparation of Chinese herbal recipe | US-2005158402-A1 | [80] |

| Bryophyllum pinnatum | Herbal composition for the treatment of burns | WO-2020201847-A1 | [81] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Delgado-González, C.R.; Sharma, A.; Islas-Pelcastre, M.; Saucedo-García, M.; Aquino-Torres, E.; Pacheco-Trejo, J.; Armenta-Jaime, S.; Rivero-Pérez, N.; Madariaga-Navarrete, A. From Traditional Use to Molecular Mechanisms: A Bioinformatic and Pharmacological Review of the Genus Kalanchoe with In Silico Evidence. BioTech 2025, 14, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040097

Delgado-González CR, Sharma A, Islas-Pelcastre M, Saucedo-García M, Aquino-Torres E, Pacheco-Trejo J, Armenta-Jaime S, Rivero-Pérez N, Madariaga-Navarrete A. From Traditional Use to Molecular Mechanisms: A Bioinformatic and Pharmacological Review of the Genus Kalanchoe with In Silico Evidence. BioTech. 2025; 14(4):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040097

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelgado-González, Cristián Raziel, Ashutosh Sharma, Margarita Islas-Pelcastre, Mariana Saucedo-García, Eliazar Aquino-Torres, Jaime Pacheco-Trejo, Silvia Armenta-Jaime, Nallely Rivero-Pérez, and Alfredo Madariaga-Navarrete. 2025. "From Traditional Use to Molecular Mechanisms: A Bioinformatic and Pharmacological Review of the Genus Kalanchoe with In Silico Evidence" BioTech 14, no. 4: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040097

APA StyleDelgado-González, C. R., Sharma, A., Islas-Pelcastre, M., Saucedo-García, M., Aquino-Torres, E., Pacheco-Trejo, J., Armenta-Jaime, S., Rivero-Pérez, N., & Madariaga-Navarrete, A. (2025). From Traditional Use to Molecular Mechanisms: A Bioinformatic and Pharmacological Review of the Genus Kalanchoe with In Silico Evidence. BioTech, 14(4), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040097