Lowly Expressed Toxin Transcripts in Poorly Characterized Myanmar Russell’s Viper Venom Gland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

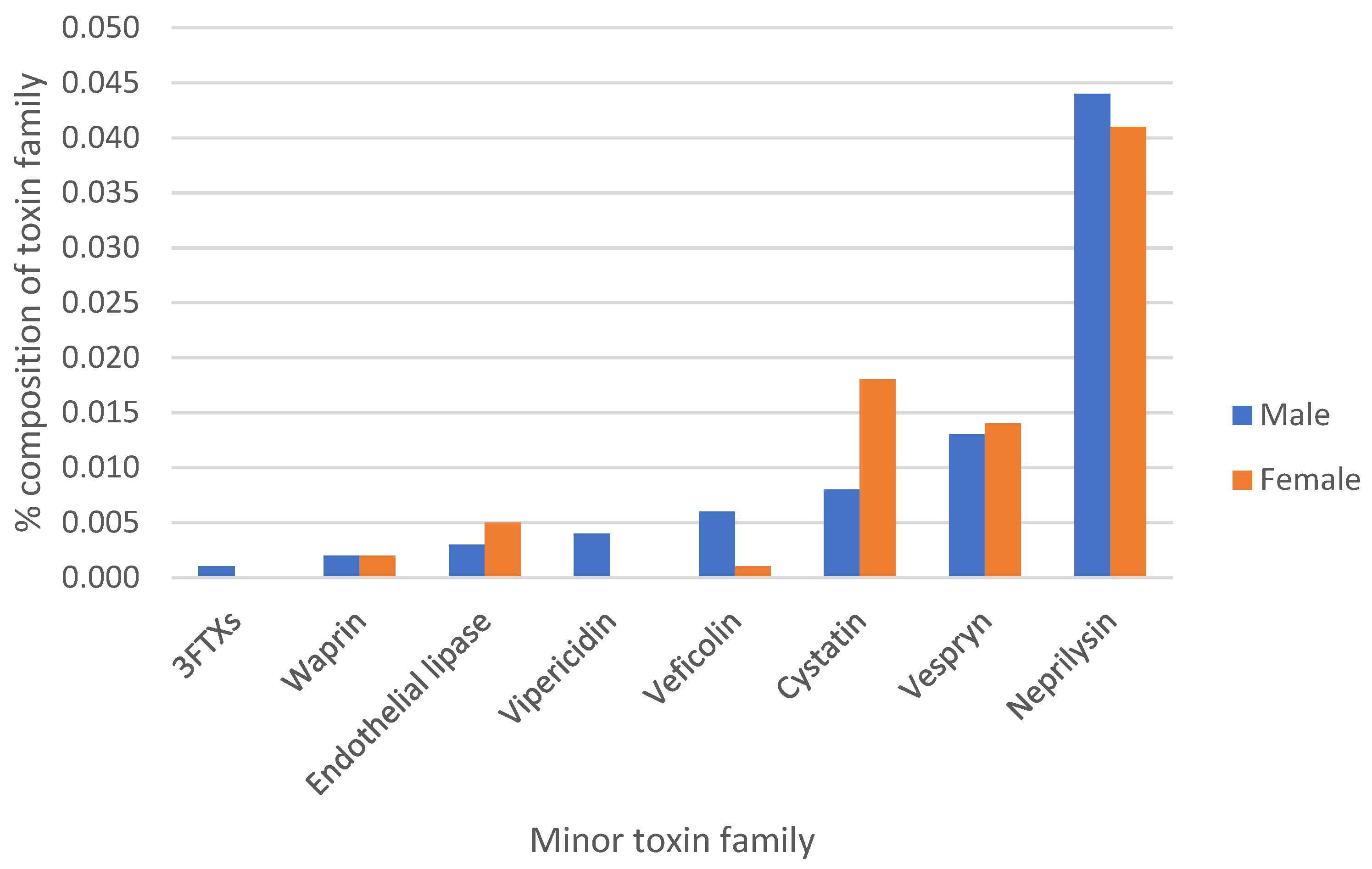

3.1. Classification and Expression Profile of Venom Gland Transcripts

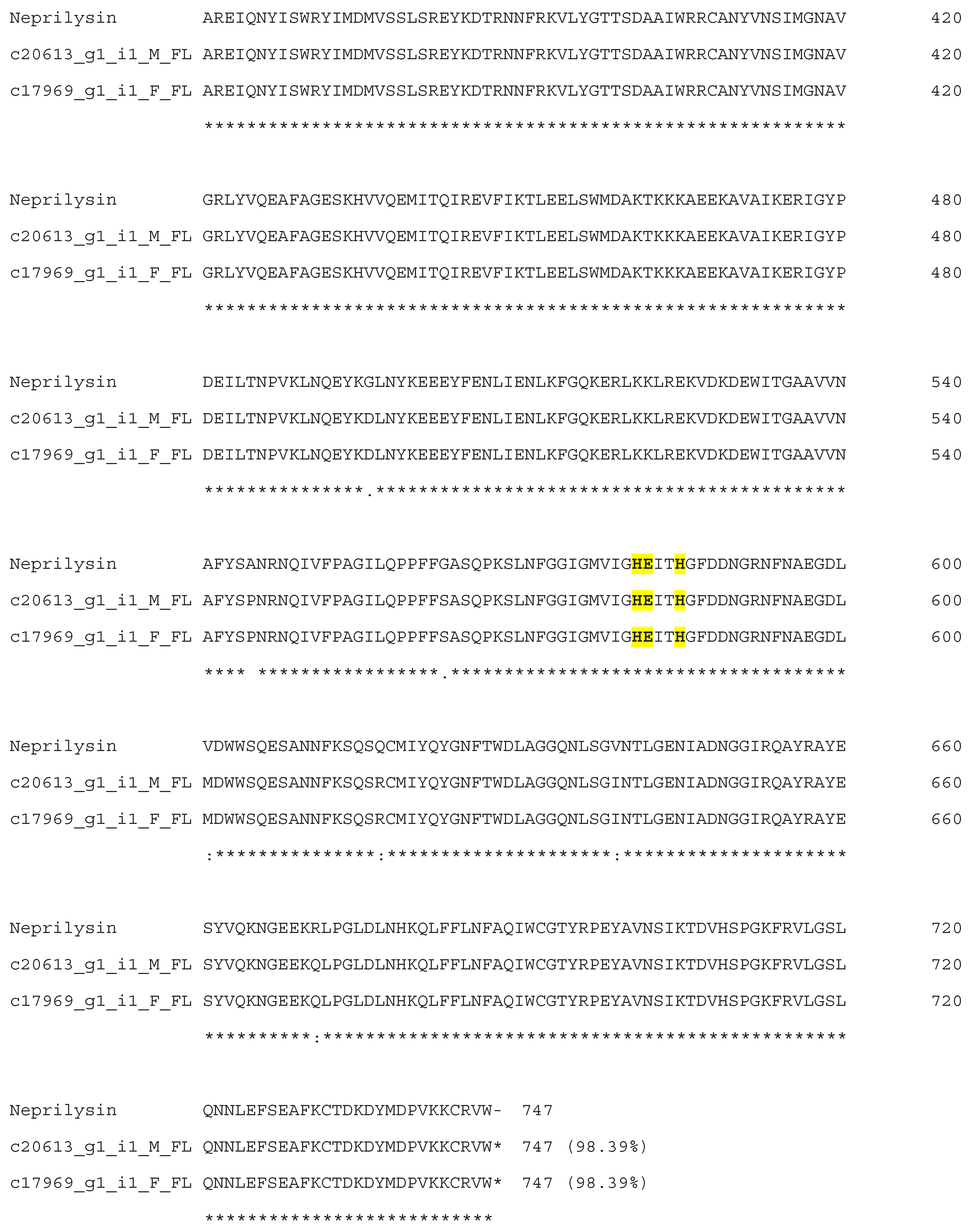

3.2. Neprilysins

3.3. Snake Venom Cystatins

3.4. Waprins

3.5. Cathelicidins

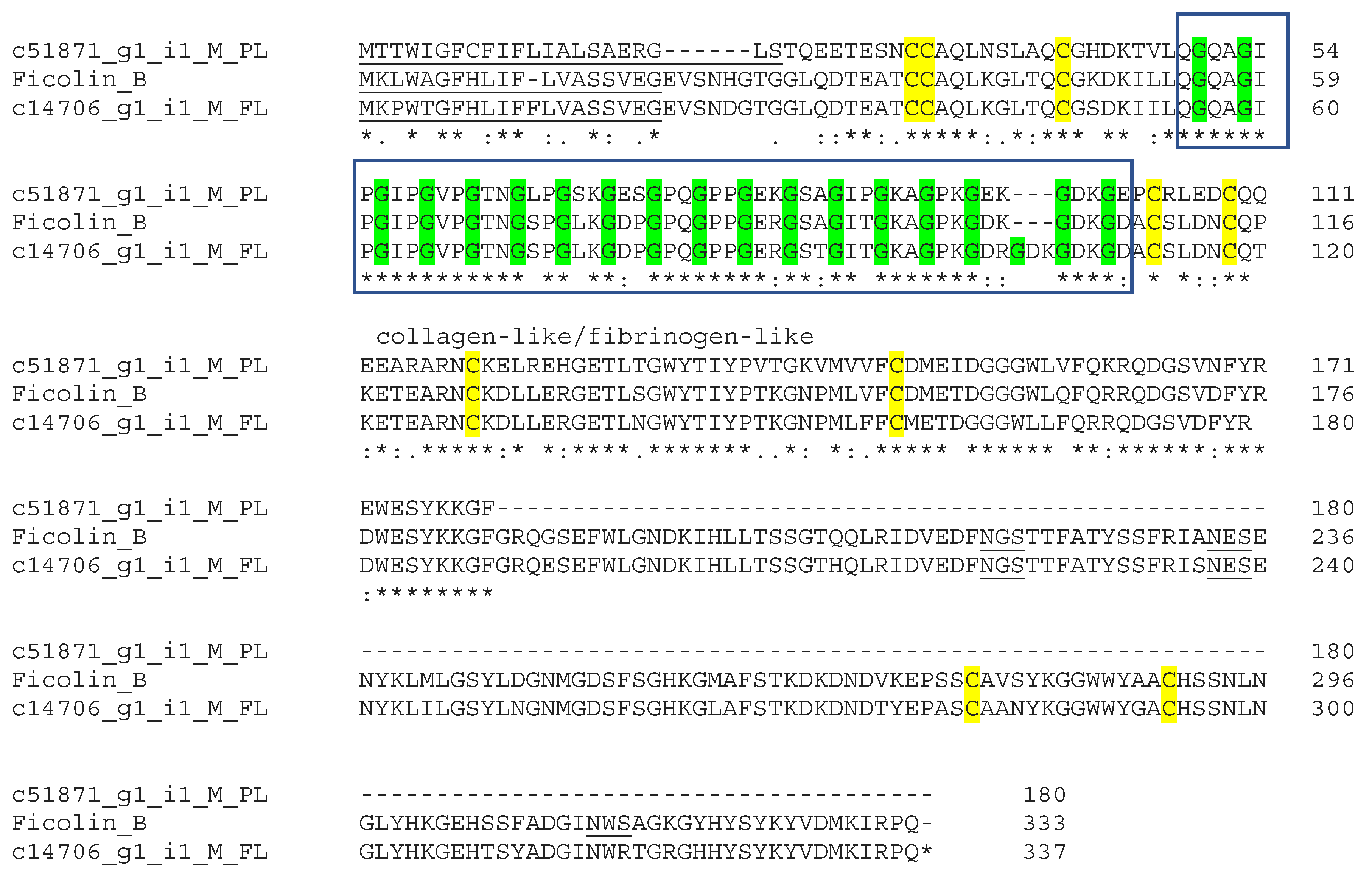

3.6. Veficolins

3.7. Endothelial Lipases

3.8. Vespryns

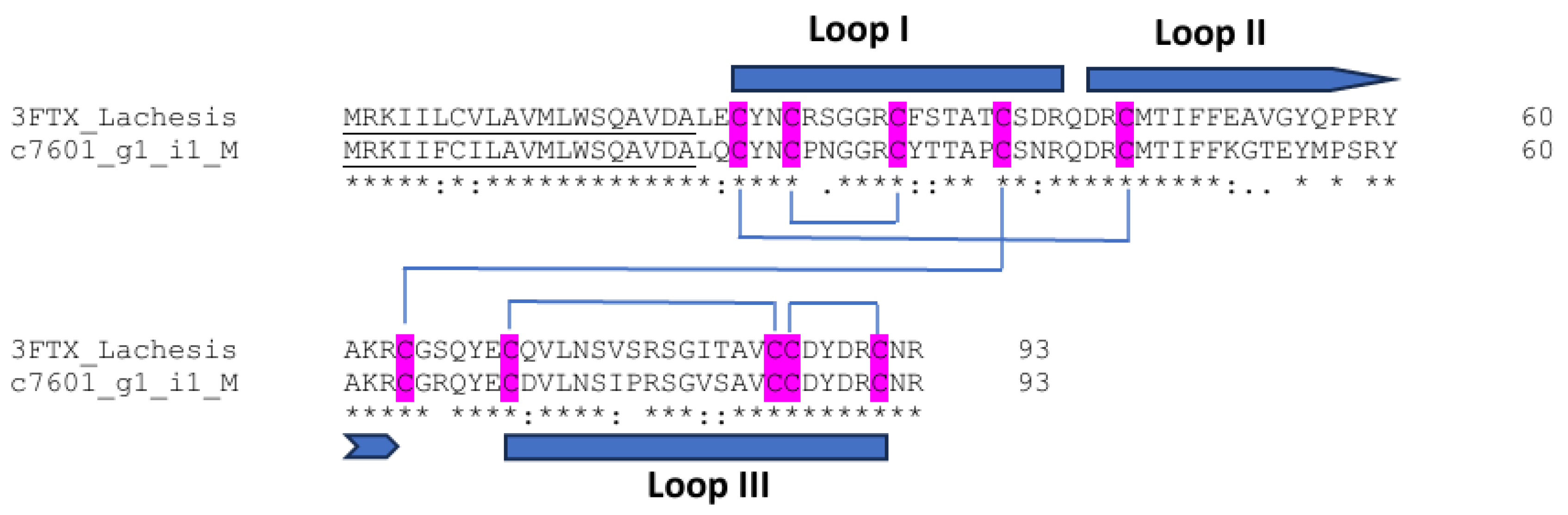

3.9. Three-Finger Toxins

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Health. Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Ministry of Health. Public Health Statistics 2017–2019; Ministry of Health: Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, 2021.

- Aye, K.-P.; Thanachartwet, V.; Soe, C.; Desakorn, V.; Chamnanchanunt, V.; Sahassananda, D.; Supaporn, T.; Sitprija, V. Predictive factors for death after snake envenomation in Myanmar. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2018, 29, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Alfred, S.; Bates, D.; Mahmood, M.A.; Warrell, D.; Cumming, R.; Thwin, K.T.; Thein, M.M.; Thant, M.; Naung, Z.M.; et al. Twelve month prospective study of snakebite in a major teaching hospital in Mandalay, Myanmar; Myanmar Snakebite Project (MSP). Toxicon X 2019, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risch, M.; Georgieva, D.; von Bergen, M.; Jehmlich, N.; Genov, N.; Arni, R.K.; Betzel, C. Snake venomics of the Siamese Russell’s viper (Daboia russelli siamensis)—Relation to pharmacological activities. J. Proteom. 2009, 72, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.Y.; Tan, N.H.; Tan, C.H. Venom proteomics and antivenom neutralization for the Chinese eastern Russell’s viper, Daboia siamensis from Guangxi and Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pla, D.; Sanz, L.; Quesada-Bernat, S.; Villalta, M.; Baal, J.; Chowdhury, M.A.W.; Leόn, G.; Gutiérrez, J.M.; Kuch, U.; Calvete, J.J. Polyvenomics of Daboia russelii across the Indian subcontinent. Bioactivities and comparative in vivo neutralization and in vitro third-generation antivenomics of antivenoms against venoms from India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. J. Proteom. 2019, 207, 103443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Alfred, S.; Zaw, A.; Gentili, S.; Chataway, T.; Peh, C.A.; Hurtado, P.; White, J.; Wiese, M.A. A demonstration of variation in venom composition of Daboia russelii (Russell’s viper), a significantly important snake of Myanmar, by tandem mass spectrometry. Toxicon 2019, 158, S44–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, K.T.; Macrander, J.; Vasieva, O.; Rojnuckarin, P. Exploring toxin genes of Myanmar Russell’s viper, Daboia siamensis, through de novo venom gland transcriptomics. Toxins 2023, 15, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrell, D.A.; Williams, D.J. Clinical aspects of snakebite envenoming and its treatment in low-resource settings. Lancet 2023, 401, 1382–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvete, J.J.; Juárez, P.; Sanz, L. Snake venomics. Strategy and applications. J. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 42, 1405–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudresha, G.V.; Bhatia, S.; Samanta, A.; Nayak, M.; Sunagar, K. Dissecting Daboia: Investigating synergistic effects of Russell’s viper venom toxins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 321, 146533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girish, K.S.; Shashidharamurthy, R.; Nagaraju, S.; Gowda, T.V.; Kemparaju, K. Isolation and characterization of hyaluronidase a “spreading factor” from Indian cobra (Naja naja) venom. Biochimie 2004, 86, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modahl, C.M.; Brahma, R.K.; Koh, C.Y.; Shioi, N.; Kini, R.M. Omics Technologies for profiling toxin diversity and evolution in snake venom: Impacts on the discovery of therapeutic and diagnostic agents. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2020, 8, 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunagar, K.; Morgenstern, D.; Reitzel, A.M.; Moran, Y. Ecological venomics: How genomics, transcriptomics and proteomics can shed new light on the ecology and evolution of venom. J. Proteom. 2016, 135, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saethang, T.; Somparn, P.; Payungporn, S.; Sriswasdi, S.; Yee, K.T.; Hodge, K.; Knepper, M.A.; Chanhome, L.; Khow, O.; Chaiyabutr, N.; et al. I dentification of Daboia siamensis venom using integrated multi-omics data. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.Y.; Tan, C.H.; Chanhome, L.; Tan, N.H. Comparative venom gland transcriptomics of Naja kaouthia (monocled cobra) from Malaysia and Thailand: Elucidating geographical venom variation and insights into sequence novelty. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junqueira-de-Azevedo, I.L.M.; Bastos, C.M.V.; Ho, P.L.; Luna, M.S.; Yamanouye, N.; Casewell, N.R. Venom-related transcripts from Bothrops jararaca tissues provide novel molecular insights into the production and evolution of snake venom. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 32, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonk, F.J.; Casewell, N.R.; Henkel, C.V.; Heimberg, A.M.; Jansen, H.J.; McCleary, R.J.R.; Kerkkamp, H.M.E.; Vos, R.A.; Guerreiro, I.; Calvete, J.J.; et al. The king cobra genome reveals dynamic gene evolution and adaptation in the snake venom system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20651–20656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, D.; Kumar, S. Mini-Review, Snake venom: A potent anticancer agent. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2012, 13, 4855–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanbhag, V.K.L. Applications of snake venoms in treatment of cancer. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015, 5, 275–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguiura, N.; Sanches, L.; Duarte, P.V.; Sulca-Lόpez, M.A. Past, present, and future of naturally occurring antimicrobials related to snake venoms. Animals 2023, 13, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junqueira-de-Azevedo, I.L.M.; Ching, A.T.C.; Carvalho, E.; Faria, F.; Nishiyama, M.Y.; Ho, P.L.; Diniz, M.R.V. Lachesis muta (Viperidae) cDNAs reveal diverging pit viper molecules and scaffolds typical of cobra (Elapidae) venoms: Implications for snake toxin repertoire evolution. Genetics 2006, 173, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q.; et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrander, J.; Panda, J.; Janies, D.; Daly, M.; Reitzel, A.M. Venomix: A simple bioinformatic pipeline for identifying and characterizing toxin gene candidates from transcriptomic data. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, F.; Pearce, M.; Tivey, A.R.N.; Basutkar, P.; Lee, J.; Edbali, O.; Madhusoodanan, N.; Kolesnikov, A.; Lopez, R. Search and sequence analysis tools services from EMBL-EBI in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W276–W279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teufel, F.; Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Johansen, A.R.; Gίslason, M.H.; Pihl, S.I.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Winther, O.; Brunak, S.; von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein language models. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1023–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxme, R.R.S.; Khochare, S.; Attarde, S.; Kaur, N.; Jaikumar, P.; Shaikh, N.Y.; Aharoni, R.; Primor, N.; Hawlena, D.; Moran, Y.; et al. The Middle Eastern cousin: Comparative venomics of Daboia palaestinae and Daboia russelii. Toxins 2022, 14, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, M.A.; Kenny, A.J. The purification and specificity of a neutral endopeptidase from rabbit kidney brush border. Biochem. J. 1974, 137, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, B.; Nair, A.P.; Misra, A.; Scott, C.Z.; Mahar, J.H.; Fedson, S. Neprilysin inhibitors in heart failure: The science, mechanism of action, clinical studies, and unanswered questions. JACC Basic. Transl. Sci. 2023, 8, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casewell, N.R.; Harrison, R.A.; Wüster, W.; Wagstaff, S.C. Comparative venom gland transcriptome surveys of the saw-scaled vipers (Viperidae: Echis) reveal substantial intra-family gene diversity and novel venom transcripts. BMC Genom. 2009, 10, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunalan, S.; Othman, I.; Hassan, S.S.; Hodgson, W.C. Proteomic characterization of two medically important Malaysian snake venoms, Calloselasma rhodostoma (Malayan pit viper) and Ophiophagus hannah (king cobra). Toxins 2018, 10, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, S.M.; de Oliveira, U.C.; Nishiyama-Jr, M.Y.; Tashima, A.K.; da Silva Junior, P.I. Presence of a neprilysin on Avicularia juruensis (Mygalomorphae: Theraphosidae) venom. Toxin Rev. 2022, 41, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, H. Snake venom protease inhibitors: Enhanced identification, expanding biological function, and promising future. In Snake Venoms, Toxinology, Dordrecht; Inagaki, H., Vogel, C.-W., Mukherjee, A.K., Rahmy, T.R., Gopalakrishnakone, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urra, F.A.; Araya-Maturana, R. Targeting metastasis with snake toxins: Molecular mechanisms. Toxins 2017, 9, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.L. Cystatins as regulators of cancer. Med. Res. Arch. 2017, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dickinson, D.P. Salivary (SD-type) cystatins: Over one billion years in the making—But to what purpose? Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2002, 13, 485–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, N.; Xie, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Lin, X.; Lin, J. Inhibition of invasion and metastasis of MHCC97H cells by expression of snake venom cystatin through reduction of proteinases activity and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2011, 34, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Tang, N.; Lin, Y.; Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Lin, J. Recombinant adenovirus snake venom cystatin inhibits the growth, invasion, and metastasis of B16F10 cells in vitro and in vivo. Melanoma Res. 2013, 23, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Tang, N.; Wan, R.; Qi, Y.; Lin, X.; Lin, J. Recombinant snake venom cystatin inhibits tumor angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo associated with downregulation of VEGF-A165, Flt-1 and bFGF. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.M.; Wong, H.Y.; Desai, M.; Moochhala, S.; Kuchel, P.W.; Kini, R.M. Identification of a novel family of proteins in snake venoms. Purification and structural characterization of nawaprin from Naja nigricollis snake venom. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 40097–40104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, T.N.W.; Sunagar, K.; Undheim, E.A.B.; Koludarov, I.; Chan, A.H.C.; Sanders, K.; Ali, S.A.; Hendrikx, I.; Dunstan, N.; Fry, B.G. Venom down under: Dynamic evolution of Australian elapid snake toxins. Toxins 2013, 5, 2621–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, D.G.; Fry, B.G.; Alewood, P.; Kumar, P.P.; Kini, R.M. Antimicrobial activity of omwaprin, a new member of the waprin family of snake venom proteins. Biochem. J. 2007, 402, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.-C.; Lin, H.-C.; Yang, D.; Ye, X.; Li, Z.-G. Disulfide bridges in defensins. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2015, 16, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barros, E.; Goncalves, R.M.; Cardoso, M.H.; Santos, N.C.; Franco, O.L.; Cândido, E.S. Snake venom cathelicidins as natural antimicrobial peptides. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Aubesart, A.; Defaus, S.; Pérez-Peinado, C.; Sandín, D.; Torrent, M.; Jiménez, M.A.; Andreu, D. Examining topoisomers of a snake-venom-derived peptide for improved antimicrobial and antitumoral properties. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hong, J.; Liu, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, R.; Wu, J.; Wang, A.; Lin, D.; Lai, R. Snake cathelicidin from Bungarus fasciatus is a potent peptide antibiotics. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Lan, X.-Q.; Du, Y.; Chen, P.-Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, F.; Lee, W.-H.; Zhang, Y. King cobra peptide OH-CATH30 as a potential candidate drug through clinic drug-resistant isolates. Zool. Res. 2018, 39, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakinuma, Y.; Endo, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Nakata, M.; Matsushita, M.; Takenoshita, S.; Fujita, T. Molecular cloning and characterization of novel ficolins from Xenopus laevis. Immunogenetics 2003, 55, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ompraba, G.; Chapeaurouge, A.; Doley, R.; Devi, K.R.; Padmanaban, P.; Venkatraman, C.; Velmurugan, D.; Lin, Q.; Kini, R.M. Identification of a novel family of snake venom proteins veficolins from Cerberus rynchops using a venom gland transcriptomics and proteomics approach. J. Proteome Res. 2010, 9, 1882–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.Y.; Hirata, K.; Ishida, T.; Quertermous, T.; Cooper, A.D. Endothelial lipase: A new lipase on the block. J. Lipid Res. 2002, 43, 1763–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, L.D.; Vind, J.; Oxenbøll, K.M.; Svendsen, A.; Patkar, S. Phospholipases and their industrial applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 74, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrow, A.L.; Olson, M.W.; Xin, H.; Burke, S.L.; Smith, C.; Schalk-Hihi, C.; Williams, R.; Bayoumy, S.S.; Deckman, I.C.; Todd, M.J.; et al. A novel fluorogenic substrate for the measurement of endothelial lipase activity. J. Lipid Res. 2011, 52, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Griffon, N.; Jin, W.; Petty, T.J.; Millar, J.; Badellino, K.O.; Saven, J.G.; Marchadier, D.H.; Kempner, E.S.; Billheimer, J.; Glick, J.M.; et al. Identification of the active form of endothelial lipases, a homodimer in a head-to-tail conformation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 23322–23330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.E.; Han, S.-Y.; Wolfson, B.; Zhou, Q. The role of endothelial lipase in lipid metabolism, inflammation, and cancer. Histol. Histopathol. 2018, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hempel, B.-F.; Damm, M.; Mrinalini; Göçmen, B.; Karış, M.; Nalbantsoy, A.; Kini, R.M.; Sűssmuth, R.D. Extended snake venomics by top-down in-source decay: Investigating the newly discovered Anatolian meadow viper subspecies, Vipers anatolica senliki. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 1731–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrêa-Netto, C.; Junqueira-de-Azevedo, I.L.M.; Silva, D.A.; Ho, P.L.; Leitão-de-Araújo, M.; Alves, M.L.M.; Sanz, L.; Foguel, D.; Zingali, R.B.; Calvete, J.J. Snake venomics and venom gland transcriptomic analysis of Brazilian coral snakes, Micrurus altirostris and M. corallinus. J. Proteom. 2011, 74, 1795–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuh, F.P.; Wong, P.T.H.; Kumar, P.P.; Hodgson, W.C.; Kini, R.M. Ohanin, a novel protein from king cobra venom, induces hypolocomotion and hyperalgesia in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 13137–13147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrini-França, J.; Cologna, C.T.; Pucca, M.B.; Bordon, K.C.F.; Amorim, F.G.; Anjolette, F.A.P.; Cordeiro, F.A.; Wiezel, G.A.; Cerni, F.A.; Pinheiro-Junior, E.L.; et al. Minor snake venom proteins: Structure, function and potential applications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 824–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pung, Y.F.; Kumar, S.V.; Rajagopalan, N.; Fry, B.G.; Kumar, P.P.; Kini, R.M. Ohanin, a novel protein from king cobra venom: Its cDNA and genomic organization. Gene 2006, 371, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kini, R.M. Evolution of three-finger toxins—A versatile mini protein scaffold. Acta Chim. Slov. 2011, 58, 693–701. [Google Scholar]

- Utkin, Y.N. Three-finger toxins, a deadly weapon of elapid venom—Milestones of discovery. Toxicon 2013, 62, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirthanan, S.; Charpantier, E.; Gopalakrishnakone, P.; Gwee, M.C.E.; Khoo, H.E.; Cheah, L.S.; Kini, R.M.; Bertrand, D. Neuromuscular effects of candoxin, a novel toxin from the venom of the Malayan krait (Bungarus candidus). Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 139, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlak, J.; Mackessy, S.P.; Fry, B.G.; Bhatia, M.; Mourier, G.; Fruchart-Gaillard, C.; Servent, D.; Ménez, R.; Stura, E.; Ménez, A.; et al. Denmotoxin, a three-finger toxin from the colubrid snake Boiga dendrophila (mangrove catsnake) with bird-specific activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 29030–29041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utkin, Y.N. Last decade update for three-finger toxins: Newly emerging structures and biological activities. World J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 10, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, B.G.; Wüster, W.; Kini, R.M.; Brusic, V.; Khan, A.; Venkataraman, D.; Rooney, A.P. Molecular evolution and phylogeny of elapid snake venom three-finger toxins. J. Mol. Evol. 2003, 57, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelke, R.R.J.; Sathish, S.; Gowda, T.V. Isolation and characterization of a novel postsynaptic/cytotoxic neurotoxin from Daboia russelli russelli venom. J. Pept. Res. 2002, 59, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarova, Y.V.; Kryukova, E.V.; Shelukhina, I.V.; Lebedev, D.S.; Andreeva, T.V.; Ryazantsev, D.Y.; Balandin, S.V.; Ovchinnikova, T.V.; Tsetlin, V.I.; Utkin, Y.N. The first recombinant viper three-finger toxins: Inhibition of muscle and neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 2018, 479, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunagar, K.; Jackson, T.N.W.; Undheim, E.A.B.; Ali, S.A.; Antunes, A.; Fry, B.G. Three-fingered RAVERs: Rapid accumulation of variations in exposed residues of snake venom toxins. Toxins 2013, 5, 2172–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, A.; Sajevic, T.; Pungerčar, J.; Križaj, I. Comparative study of the proteome and transcriptome of the venom of the most venomous European viper: Discovery of a new subclass of ancestral snake venom metalloproteinases precursor-derived proteins. J. Proteome Res. 2019, 18, 2287–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.S.; Boldrini-Franҫa, J.; Fonseca, F.P.P.; de la Torre, P.; Henrique-Silva, F.; Sanz, L.; Calvete, J.J.; Rodrigues, V.M. Combined snake venomics and venom gland transcriptomic analysis of Bothropoides pauloensis. J. Proteom. 2012, 75, 2707–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff, S.C.; Sanz, L.; Juárez, P.; Harrison, R.A.; Calvete, J.J. Combined snake venomics and venom gland transcriptomic analysis of the ocellated carpet viper, Echis ocellatus. J. Proteom. 2009, 71, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, K.; Nampoothiri, M.; Khandibharad, S.; Singh, S.; Nayak, A.G.; Hariharapura, R.C. Proteomic diversity of Russell’s viper venom: Exploring PLA2 isoforms, pharmacological effects, and inhibitory approaches. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 3569–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- op den Brouw, B.; Coimbra, F.C.P.; Casewell, N.R.; Ali, S.A.; Vonk, F.J.; Fry, B.G. A genus-wide bioactivity analysis of Daboia (Viperinae: Viperidae) viper venoms reveals widespread variation in haemotoxic properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.R.; Jin, Y.; Wu, J.B.; Chen, R.Q.; Jia, Y.H.; Wang, W.Y.; Xiong, Y.L.; Zhang, Y. Characterization and molecular cloning of dabocetin, a potent antiplatelet C-type lectin-like protein from Daboia russellii siamensis venom. Toxicon 2006, 47, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, A.K.; Mackessy, S.P. Pharmacological properties and pathophysiological significance of a Kunitz-type protease inhibitor (Rusvikunin-II) and its protein complex (Rusvikunin complex) purified from Daboia russelii russelii venom. Toxicon 2014, 89, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, A.A.; Estrada, J.C.; David, V.; Wermelinger, L.S.; Almeida, F.C.L.; Zingali, R.B. Structure-function relationship of the disintegrin family: Sequence signature and integrin interaction. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 783301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thwin, M.-M.; Gopalakrishnakone, P.; Yuen, R.; Tan, C.H. A major lethal factor of the venom of Burmese Russell’s viper (Daboia russellil siamensis): Isolation, n-terminal sequencing and biological activities of daboiatoxin. Toxicon 1995, 33, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, H.; Fujimoto, Z.; Atoda, H.; Morita, T. Crystal structure of an anticoagulant protein in complex with the Gla domain of factor X. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001, 98, 7230–7234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R.; Mukherjee, A.K. A brief appraisal on Russell’s viper venom (Daboia russelii russelii) proteinases. In Snake Venoms; Inagaki, H., Vogel, C.W., Mukherjee, A., Rahmy, T., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, S.; Huang, C. Synergistic strategies of predominant toxins in snake venoms. Toxicol. Lett. 2018, 287, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordon, K.C.; Perino, M.G.; Giglio, J.R.; Arantes, E.C. Isolation, enzymatic characterization and antiedematogenic activity of the first reported rattlesnake hyaluronidase from Crotalus durissus terrificus venom. Biochimie 2012, 94, 2740–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiyabutr, N.; Chanhome, L.; Vasaruchapong, T.; Laoungbua, P.; Khow, O.; Rungsipipat, A.; Sitprija, V. The pathophysiological effects of Russell’s viper (Daboia siamensis) venom and its fractions in the isolated perfused rabbit kidney model: A potential role for platelet activating factor. Toxicon X 2020, 7, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiyabutr, N.; Noiprom, J.; Promruangreang, K.; Vasaruchapong, T.; Laoungbua, P.; Khow, O.; Chanhome, L.; Sitprija, V. Acute phase reactions in Daboia siamensis venom and fraction-induced acute kidney injury: The role of oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways in in vivo rabbit and ex vivo rabbit kidney models. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 30, e20230070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Family | Predicted Function | No. of Sequences/No. of Mature/ No. of Unique ORF | Amino Acid | Domain Structure | Conserved Motifs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neprilysin | Vasoactive peptide inactivation | 2/2/1 | 750 | Zinc Metalloendopeptidases and N-terminal Transmembrane Domain | HExxH active site |

| Cystatin | Protease inhibition Anti-metastatic effect | 5/5/3 | 175 | Cysteine Protease Inhibitor | QxVxG and PW |

| Waprin | Antibacterial activity Protease inhibition | 1/1/1 | 133 | Two Whey Acid Protein (WEP) Domains | Eight disulfide bonds KxGxCP motif |

| Vipericidin | Antimicrobial activity | 1/1/1 | 172 | Cathelicidin (Antimicrobial Peptide) Domain | Amphiphile peptide causing membrane disruption |

| Veficolin | Platelet aggregation Complement activation | 2/1/2 | 337 | Collagen-like Domain Fibrinogen-like Domain | Gxx collagen-like repeat |

| Vespryn (Ohanin) | Neurotoxicity | 8/0/7 | 256–549 | PRY-SPRY Domain | LPD, WEVE, and LDYE motif |

| Three-finger toxins | Neurotoxicity Tissue damage | 1/1/1 | 93 | Three Loops Extending From The Core | Five disulfide bridges for central core stabilization |

| Endothelial lipases | Unknown | 9/1/4 | 316–493 | Triglyceride lipase | S-(GxSxG)-H-D catalytic triad RxDxxD Ca2+ binding |

| No | Contig ID | Annotation | Accession No. | Species | Amino Acid Length | TPM Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | c4051_g2_i1_F_FL | cystatin-2 | J3SE80.1 | Crotalus adamanteus | 137 | 137 |

| 2 | c8190_g1_i1_M_FL | cystatin-2 | J3SE80.1 | Crotalus adamanteus | 137 | 19.77 |

| 3 | c17744_g1_i1_F_FL | cystatin-1 | XP_015672096.1 | Protobothrops mucrosquamatus | 175 | 8.99 |

| 4 | c12696_g1_i1_M_FL | cystatin-A | XP_015667611.1 | Protobothrops mucrosquamatus | 98 | 113.67 |

| 5 | c7765_g2_i1_F_FL | cystatin-A | XP_015667611.1 | Protobothrops mucrosquamatus | 98 | 36.79 |

| Antimicrobial Peptides | Species | Common Name | Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| NA-CATH | Naja atra | Chinese cobra | B6S2X0 |

| OH-CATH | Ophiophagus hannah | King cobra | B6S2X2 |

| BF-CATH | Bungarus fasciatus | Banded krait | B6D434 |

| Pt-CRAMP1 | Pseudonaja textilis | Eastern brown snake | U5KJJ1 |

| Pt-CRAMP2 | Pseudonaja textilis | Eastern brown snake | U5KJM6 |

| Crotalicidin (Ctn) | Crotalus durissus terrificus | Eastern brown snake | U5KJM4 |

| Bastroxicidin (BatxC) | Bothrops atrox | South American pit viper | U5KJC9 |

| Lutzicidin | Bothrops lutzi | South American pit viper | U5KJT7 |

| No. | Contig ID | Amino Acid Length | LDP Motif | WEVE Motif | LDYE Motif | TPM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | c18829_g1_i1_M_FL | 549 | LDP | WEVE | LDYE | 12.14 |

| 2. | c11270_g2_i1_F_FL | 493 | LDP | WEVE | LDYE | 5.70 |

| 3. | c18865_g3_i1_M_FL | 255 | LDP | WELE | LDYV | 9.30 |

| 4. | c19046_g2_i2_M_FL | 516 | IDG | WQVF | LDYK | 2.32 |

| 5. | c10539_g2_i1_F_FL | 516 | IDG | WQVF | LDYK | 2.25 |

| 6. | c17242_g1_i1_M_FL | 286 | LDP | WVVE | LEF | 5.78 |

| 7. | c17242_g1_i2_M_FL | 302 | LDP | WVVE | LKH | 4.66 |

| 8. | c20069_g2_i1_M_FL | 482 | LDP | WEVT | LSF | 6.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yee, K.T.; Macrander, J.; Vasieva, O.; Rojnuckarin, P. Lowly Expressed Toxin Transcripts in Poorly Characterized Myanmar Russell’s Viper Venom Gland. BioTech 2025, 14, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040096

Yee KT, Macrander J, Vasieva O, Rojnuckarin P. Lowly Expressed Toxin Transcripts in Poorly Characterized Myanmar Russell’s Viper Venom Gland. BioTech. 2025; 14(4):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040096

Chicago/Turabian StyleYee, Khin Than, Jason Macrander, Olga Vasieva, and Ponlapat Rojnuckarin. 2025. "Lowly Expressed Toxin Transcripts in Poorly Characterized Myanmar Russell’s Viper Venom Gland" BioTech 14, no. 4: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040096

APA StyleYee, K. T., Macrander, J., Vasieva, O., & Rojnuckarin, P. (2025). Lowly Expressed Toxin Transcripts in Poorly Characterized Myanmar Russell’s Viper Venom Gland. BioTech, 14(4), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/biotech14040096